Abstract

In all kingdoms of life, ATP Binding Cassette (ABC) transporters participate in many physiological and pathological processes. Despite the diversity of their functions, they have been considered to operate by a largely conserved mechanism. One deviant is the vitamin B12 transporter BtuCD that has been shown to operate by a distinct mechanism. However, it is unknown if this deviation is an exotic example, perhaps arising from the nature of the transported moiety. Here we compared two ABC importers of identical substrate specificity (molybdate/tungstate), and find that their interactions with their substrate binding proteins are utterly different. One system forms a high-affinity, slow-dissociating complex that is destabilized by nucleotide and substrate binding. The other forms a low-affinity, transient complex that is stabilized by ligands. The results highlight significant mechanistic divergence among ABC transporters, even when they share the same substrate specificity. We propose that these differences are correlated with the different folds of the transmembrane domains of ABC transporters.

Keywords: active transport, membrane proteins, permeation

Hydrolyzing ATP to drive transport, ATP Binding Cassette (ABC) transporters shuttle cargo molecules to and from the various cellular compartments. They participate in processes such as multidrug resistance, antigen presentation, signal transduction, DNA repair, translation, cell division, detoxification, nutrient import, and antiviral defense (1–11). Despite their diversity of roles, ABC transporters have been long considered to operate by a largely common mechanism, which has been most extensively demonstrated for the maltose transporter (12–15).

However, recent reports suggest that the vitamin B12 transporter BtuCD-F operates by a very different mechanism (16–20).

Unlike the maltose transporter, BtuCD has high basal rates of ATP hydrolysis that are only mildly stimulated by the substrate binding protein (SBP) (16). BtuCD (the transporter) and BtuF (the vitamin B12 binding protein) form an extremely stable high-affinity complex, while in the maltose system this complex is transient and is of very low affinity (21). The BtuCD-F complex is destabilized in the presence of nucleotides and substrate, and the exact opposite is true for MalFGK-E (19). These findings raise the question of whether BtuCD is a rare exception or rather represents a broader phenomenon of mechanistic diversity among ABC transporters. To address this question we have studied two ABC transporters (importers) of identical substrate specificity (tungstate/molybdate): hiMolBCA of Haemophilus influenzae and afModBCA of Archaeoglobus fulgidus (22, 23). We focused on the pivotal event of complex formation between the transporter and its SBP. This is when substrate is transferred from the binding protein to the transporter. Also, docking of the SBP to the transporter triggers catalytic transformations such as ATP hydrolysis and opening and closing of the transporter’s periplasmic and cytosolic gates (17, 18, 21, 24–30). We find that hiMolBC and afModBC interact very differently with their cognate SBPs. The results presented here underline significant mechanistic diversity among ABC transporters, even when they are of identical substrate specificity. We present a possible correlation between the observed differences and the structural fold of each system.

Results

Substrate Affinity of afModA.

The two import systems we chose to study are of identical substrate specificity (tungstate/molybdtae) but of different structural folds. afModBC has 12 transmembrane α-helices that adopt the characteristic fold of type I ABC importers. On the other hand, the 20 transmembrane α-helices of hiMolBC present a type II fold, very similar to BtuCD and HmuUV (15, 31–33). Correspondingly, the cognate SBPs are also of different structural subclasses (23, 34–36). Recently, Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) experiments demonstrated that hiMolA binds its substrates with low affinity (50–100 μM) (22). Using a similar approach we found that afModA binds molybdate with a 500–100-fold higher affinity (KD = 0.11 μM; Fig. S1A). With tungstate the sharp Δp transition precludes an accurate determination of the KD (Fig. S1B) but indicates that the affinity toward tungstate is even higher. Interestingly, binding of molybdate by afModA was endothermic, while that of tungstate was exothermic. We do not understand at this stage the source of this difference. Taken together, these results suggest that afModBC–A is a high-affinity transport system and hiMolBC–A a low-affinity one (although we have not determined the Km of transport). The complementary roles of high- and low-affinity transport systems (37) are further discussed in SI Discussion.

Stability of the Transporter–SBP Interactions.

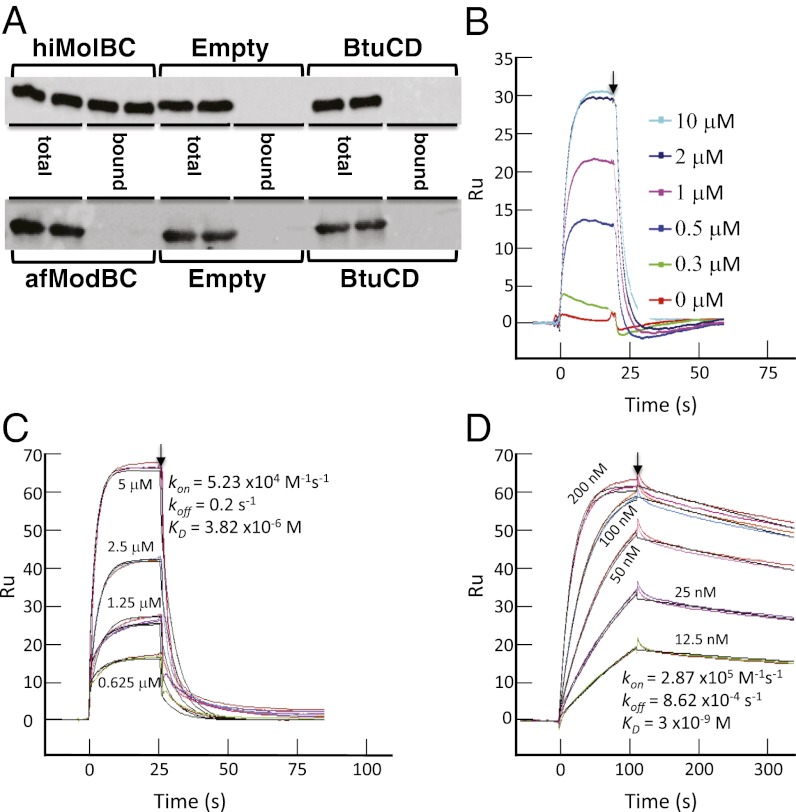

afModBC and hiMolBC were purified and reconstituted into liposomes, and to ensure complete removal of the detergent, the liposomes were washed in a detergent-free buffer. Flag-tagged SBPs (afModA or hiMolA) were added to the proteoliposomes’ suspension, and unbound material was removed by washing the liposomes with buffer. As controls we used empty liposomes or liposomes reconstituted with BtuCD. When 10 nM hiMolA was incubated with hiMolBC-liposomes, practically all of the added SBP was found in the liposome-associated fraction. No nonspecific interactions were observed between hiMolA and empty or BtuCD-liposomes (Fig. 1, Upper). Very similar results were obtained by pull-down experiments (see Materials and Methods for details) performed in detergent solution (Fig. S2A).

Fig. 1.

(A) Interaction of the binding proteins with the membrane-embedded transporters. hiMolBC (Upper) and afModBC (Lower) were purified and reconstituted into liposomes. Ten nM FLAG–hiMolA (Upper) or 5 μM FLAG–afModA (Lower) were added to the liposome suspension. Empty liposomes and liposomes reconstituted with BtuCD served as controls. The amount of total added SBP and the liposome-bound fraction was visualized by an α-FLAG antibody. Two repeats are shown. (B–D) SPR analysis of the interaction between the transporters and their binding proteins. In all panels, the end of injection and commencement of washing the biosensor chip with buffer is indicated by an arrow. (B) Two μM afModA were injected over immobilized afModBC in the absence or presence of the indicated sodium-tungstate concentrations. (C) The indicated concentrations of afModA were injected over immobilized afModBC in the presence of 75 μM sodium-tungstate. Shown are duplicates injected at random order (colored curves); the black lines are the fits using a simple 1:1 interaction model. (D) The indicated concentrations of hiMolA were injected over immobilized hiMolBC in the absence of substrate. Shown are duplicates injected at random order (colored curves); the black lines are the fits using a simple 1:1 interaction model.

In contrast, when afModA was incubated with liposomes reconstituted with afModBC, no association between the SBP and the transporter was detected (Fig. 1, Lower), even when the SBP was added at 5 μM (500-fold higher concentration than the one used with hiMolA). The same negative result was obtained in pull-down experiments in detergent solution (Fig. S2B).

These results indicate that afModBC does not form a stable complex with its cognate SBP, while hiMolBC does.

Substrate Effects on the afModBC–A Interaction.

We hypothesized that perhaps in the presence of substrate, the afModBC–A interaction will be enhanced to measurable levels. We thus repeated the above experiments in the presence of saturating substrate concentrations but still could not detect complex formation (Fig. S2C).

The pull-down and liposome experiments suffer from similar drawbacks: both methods include a wash step that is necessary to eliminate any nonspecific interactions and to remove unbound material from the “dead-space.” Thus, any transient, fast-dissociating interactions (fast koff) cannot be detected. In addition, because of the extended incubation times, these assays are largely insensitive to the kon (see also in later figures). To evaluate whether such interactions occur between afModBC and afModA, we performed surface plasmon resonance (SPR) experiments. SPR records the interaction in real time and is able to measure a broad range of kon and koff. In these experiments, a transporter is immobilized onto a flow cell of a biosensor chip, and its SBP is injected into the buffer flowing over the flow cell. A transporter-free flow cell or one immobilized with BtuCD served as controls.

When substrate-free afModA was injected, a very low response was measured, and this response marginally differed from the one recorded in the two control flow cells. However, when the same injection was repeated in the presence of increasing substrate concentrations, a robust response was recorded. The enhancing effect of substrate saturated at a substrate:SBP molar ratio of ∼1, and no further stimulation was observed at higher molar ratios (Fig. 1B). The sensogram recorded in the presence of substrate reveals the basic characteristics of the afModBC–afModA interaction. At time 0, the association phase is triggered by the injection of the SBP. The interaction reaches equilibrium after ∼5 s, and the association is maintained as long as afModA is injected. At 20” the injection is terminated and the flow cells are now washed with buffer triggering the dissociation phase. The complex rapidly dissociates, the SBP is washed away from the transporter, and baseline levels are reached within ∼10 s.

To determine the rate constants of the afModBC–A interaction, we conducted experiments where a range of concentrations of the SBP is injected over a constant concentration of the transporter. As shown in Fig. 1C, the afModBC–A interaction has a moderately fast association phase (kon = 5.23 ×104 M−1⋅s−1) and a fast dissociation phase (koff = 0.2 s−1), yielding an equilibrium affinity dissociation constant (KD) of 3.82 ×10−6 M. For comparison, Fig. 1D shows the result of a similar experiment conducted with hiMolBC–A (here performed in the absence of substrate). The association of hiMolBC–A is ∼fivefold faster than that of afModBC–A (kon = 2.87 ×105 M−1⋅s−1). Notably, hiMolBC–A dissociate ∼230-fold more slowly than afModBC–A, with koff = 8.6 ×10−4⋅s−1. Consequently, the affinity of hiMolBC–A complex formation is ∼1,000-fold higher than that of afModBC–A (3 ×10−9 M and 3.82 × 10−6 M, respectively). The kinetic rate constants measured here for hiMolBC–A are quite similar to those we reported in the past (19) when using an hiMolA preparation that had partial substrate occupancy (22).

Effects of Substrate on the hiMolBC–A Interaction.

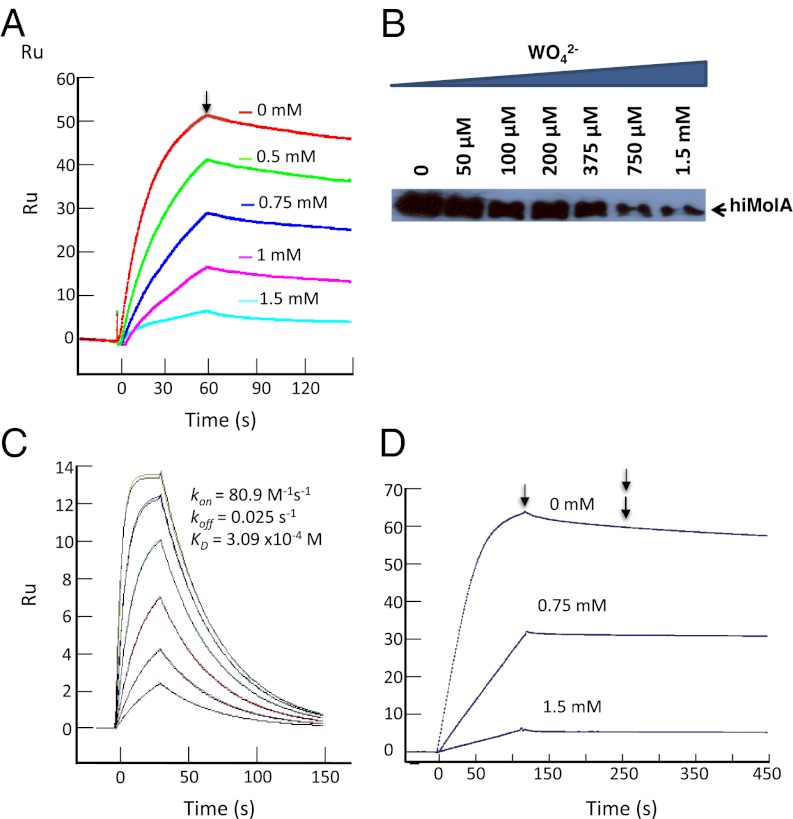

In contrast to its effect on the afModBC–A interaction, substrate was inhibitory to formation of the hiMolBC–A complex (Fig. 2, Fig. S3, and Table 1). Here, the maximal response is observed in the absence of substrate. As substrate concentrations rise, less of the hiMolBC–A complex is formed. This was observed in SPR experiments (Fig. 2A), liposomes (Fig. 2B), and detergent solution (Fig. S3A). A comparison of the dissociation phases in Fig. 2A suggests that the rate of the complex dissociation is not greatly affected by substrate, while the association phase clearly is. Determining the rate constants in the presence of 1.5 mM tungstate demonstrated that the affinity between hiMolA and hiMolBC dropped ∼20-fold, mainly due to a slower kon (Fig. S3B and Table 1). We could not measure the effects of higher substrate concentrations since the SPR signal was too low.

Fig. 2.

Effects of substrate on the interaction between hiMolA and hiMolBC. (A) Fifty nM hiMolA were injected over immobilized hiMolBC in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations of sodium-tungstate. Arrow indicates the onset of dissociation. (B) Ten nM FLAG–hiMolA were added to liposomes reconstituted with hiMolBC in the absence or presence of the indicated sodium-tungstate concentrations. The amount of liposome-bound FLAG–hiMolA was visualized with an α-FLAG antibody. (C) Direct interaction between hiMolBC and its substrate. Serial concentrations of sodium-tungstate concentrations (twofold dilutions, highest 3 mM) were injected over a high density (4,000 Ru) of immobilized hiMolBC, in the absence of hiMolA. (D) Fifty nM hiMolA were injected over hiMolBC in the absence or presence of the indicated sodium-molybdate concentrations. The end of this injection is indicated by a single arrow. At 275 s (double arrow), 1.5 mM sodium-molybdate was injected over all flow cells for 120 s.

Table 1.

Kinetic rate constants determined in SPR experiments for hiMolBC–A and afModBC–A

| Additives | ka (M–1⋅s−1) | kd (s−1) | KD (M) | |

| hiMolBC | None | (28.7 ± 0.3) × 104 | (8.62 ± 0.6) × 10−4 | 3 × 10−9 |

| Substrate (1.5 mM) | (2.3 ± 0.21) × 104 | (13.6 ± 0.28) × 10−4 | 59 × 10−9 | |

| ATP–EDTA | (6.3 ± 0.2) × 104 | (9.13 ± 0.4) × 10−4 | 14.4 × 10−9 | |

| ATP–Mg–vanadate | (3.57 ± 0.55) × 104 | (9.08 ± 0.28) × 10−4 | 25.3 × 10−9 | |

| ADP–Mg | (10.4 ± 0.15) × 104 | (8.94 ± 0.19) × 10−4 | 8.6 × 10−9 | |

| afModBC | None | No association detected | ||

| Substrate (1:1 molar ratio) | (5.23 ± 0.33) × 104 | 0.2 ± 0.07 | 3.82 × 10−6 | |

| ATP–EDTA | (2.35 ± 0.06) × 103 | (3.78 ± 0.11) × 10−3 | 1.61 × 10−6 | |

| ATP–Mg–vanadate | (1.25 ± 0.15) × 103 | (4.89 ± 0.26) × 10−4 | 0.39 × 10−6 | |

| ADP–Mg | (2.98 ± 0.09) × 103 | (2.1 ± 0.17) × 10−2 | 7 × 10−6 | |

Errors shown are SD of the fitting.

A possible interpretation of these data is that substrate-bound hiMolA docks to the transporter more slowly (and thus lowered affinity). However, in all three experimental systems, significant inhibition was only observed at substrate concentrations higher than ∼0.5 mM, which is inconsistent with the reported substrate affinity of hiMolA (22). Alternatively, high-substrate concentrations may inhibit the association by a mechanism that is unrelated to the substrate occupancy of the SBP. In this respect, we observed a direct, SBP-independent, interaction between the substrate(s) and the transporter (Fig. 2C). The KD of this interaction (309 μM) better reflects the inhibition data presented in Fig. 2 A and B. We next tested whether the hiMolBC–A complex, once assembled, is affected by substrate. Fig. 2D shows an SPR experiment where the complex was formed in the presence of 0, 0.75, or 1.5 mM molybdate. Once the complex has formed (and stabilized), an additional injection of molybdate (at 1.5 mM) was then applied. As shown, this second injection did not dissociate the complex, regardless of whether the complex was formed in the absence or presence of substrate. These results indicate that once the complex has formed it is no longer sensitive to the inhibitory effect of high-substrate concentrations.

Effects of the Nucleotides on the afModBC–A Interaction.

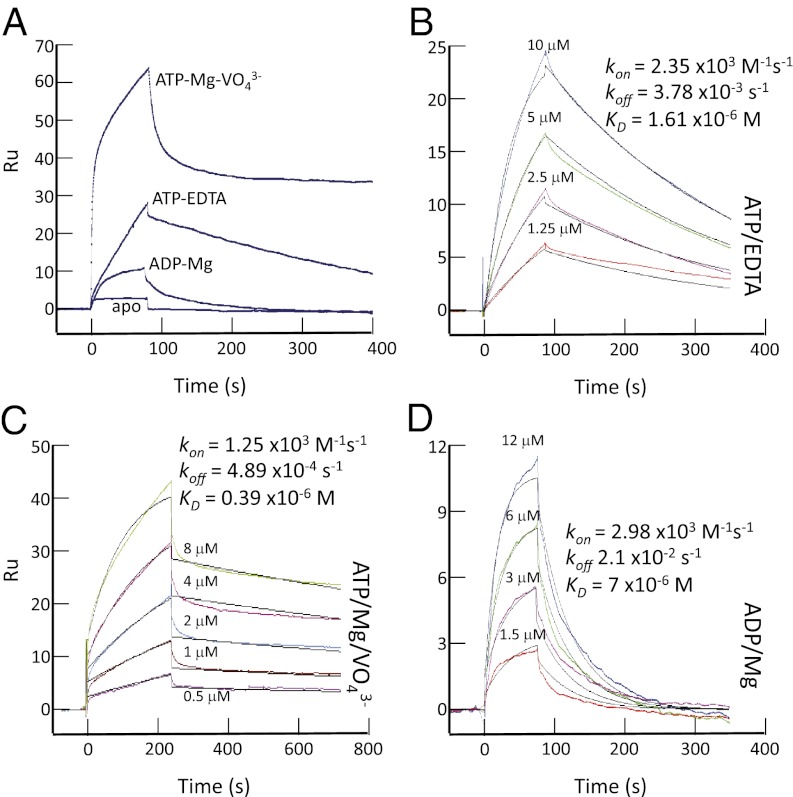

During ATP hydrolysis, an ABC transporter cycles through an ATP-bound transition (ADP∼Pi), ADP-bound, and nucleotide-free states. SPR experiments were used to test the effect of the nucleotide state of the transporters on their interaction with their SBPs. As shown above (Fig. 1A), in the absence of substrate, afModBC and afModA hardly interact. In contrast, in the presence of nucleotides (even in the absence of substrate), formation of an afModBC–A complex was readily detected. The highest signal was measured when afModBC was in the transition state (vanadate-trapped), the lowest in the ADP-bound state, and an intermediate interaction was recorded at the ATP-bound state (Fig. 3A). In the presence of vanadate, the afModBC–A interaction was clearly biphasic, with a “fast on, fast off” phase and another with a slower kon and a very slow koff. These two phases probably represent the interaction of afModA with two different transporter populations, one that was properly trapped by vanadate and one that was not. Nevertheless, for the sake of consistency and comparison with the other nucleotide states (and to hiMolBC–A), the vanadate data were fitted using a simple 1:1 interaction model. Determination of the kinetic parameters of each interaction (Fig. 3 B–D and Table 1) revealed that it is mostly the koff that differs between the nucleotide-bound states. The vanadate-trapped complex is the most stable and dissociates the slowest, the ATP-bound state at an intermediate rate, and the ADP-bound state dissociates the fastest (koff = 4.9 × 10−4⋅s−1, 2.9 × 10−3⋅s−1, and 3.4 × 10−2⋅s−1, respectively). Consequently, the vanadate-trapped state has the highest affinity toward the SBP (KD = 0.39 × 10−6 M).

Fig. 3.

Effect of nucleotides on the afModBC–A interaction in the absence of substrate. (A) Three μM afModA was injected in the absence of substrate over immobilized afModBC in the absence or presence of the indicated nucleotides. ATP, ADP, Mg, and vanadate were all added at 1 mM, EDTA at 50 μM. (B–D) Determination of the kinetic constants of the interaction between afModBC and afModA in the presence of nucleotides (but absence of substrate). (B) ATP–EDTA, (C) ATP–Mg–vanadate, and (D) ADP–Mg. The colored curves represent the experimental data, and the black lines are the fits using a simple 1:1 interaction model. Also shown are the concentrations of afModA injected and the kinetic parameters determined for each interaction.

When the above experiments were repeated in the presence of both substrate and nucleotides, very different results were obtained (Fig. 4A). Concomitant addition of 10 μM molybdate and ATP–EDTA or ADP–Mg resulted in an interaction that reverted back to “fast on, fast off” kinetics, similar to that observed in the presence of substrate but absence of nucleotide (Fig. 1 B and C). Only the vanadate-trapped state partially maintained its stability despite the presence of substrate. The results obtained from experiments conducted in liposomes were in excellent agreement with the above kinetic constants (Fig. 4B). In the absence of nucleotides, regardless of the presence of substrate, no interaction between afModBC and afModA was detected. Again, this is expected in light of the fast dissociation rate (2 × 10−1⋅s−1) of the complex under these conditions. In the presence of ADP (but absence of substrate), an extremely faint band is observed, concomitant with the slower koff of this interaction (2.1 × 10−2⋅s−1). In the ATP-bound state (in the absence of substrate), the interaction is clearly visible (koff = 3.8 × 10−3⋅s−1). In the presence of substrate, this band disappears, as the interaction is now shifted back to its “fast on, fast off” kinetics (compare Fig. 4A to Fig. 3 A and B). Finally, the highest level of complex formation is observed when the transporter is vanadate-trapped, and this interaction partially persists also in the presence of substrate.

Fig. 4.

Effect of nucleotides on the afModBC–A interaction in the presence of substrate. (A) Three μM afModA was injected in the presence of 10 μM sodium-molybdate over immobilized afModBC in the absence or presence of the indicated nucleotides. ATP, ADP, Mg, and vanadate were all added at 1 mM, EDTA at 50 μM. (B) Five μM FLAG–afModA was added to liposomes reconstituted with afModBC, in the absence or presence of the indicated concentrations of sodium-molybdate and/or nucleotides, as indicated. Shown is the amount of bound FLAG–afModA.

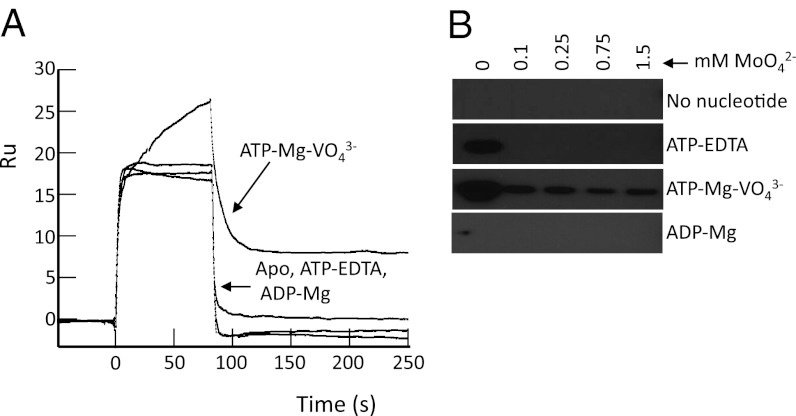

Effect of Nucleotides on the hiMolBC–A Interaction.

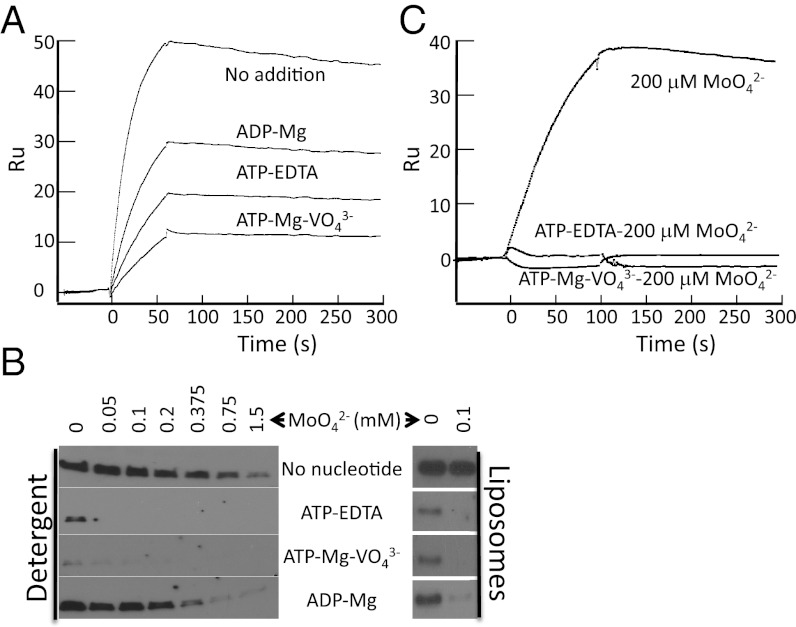

In complete contrast to their effect on the afModBC–A interaction, nucleotides inhibited the interaction between hiMolBC and hiMolA. The highest level of complex formation occurs when the transporter is nucleotide-free, and the lowest when the transporter is in the transition state (Fig. 5A). Determination of the rate constants in each nucleotide state (Fig. S4 and Table 1) revealed that similar to the effect of high-substrate concentrations, the nucleotide state of the transporter mainly affected the KD via changes in the kon. Relative to the nucleotide-free state, the affinity dropped ∼8.4-, 4.8-, and 2.8-fold in the presence of ATP–Mg–vanadate, ATP–EDTA, or ADP–Mg, respectively (Fig. S4 and Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Effect of the nucleotides on the hiMolBC–A interaction. (A) One hundred nM hiMolA were injected over hiMolBC in the absence or presence of nucleotides, as indicated. ATP, ADP, Mg, and vanadate were all added at 1 mM, EDTA at 50 μM. (B, Left) Pull-down assays in detergent solution. (Right) Sedimentation assays in liposomes. We added 10 nM FLAG–hiMolA in the absence or presence of a range of sodium-molybdate concentrations and/or nucleotides as indicated. Shown is the amount of bound FLAG–hiMolA following removal of unbound material. (C) Fifty nM hiMolA were injected over hiMolBC in the presence of 200 μM of sodium-molybdate and in the absence or presence of nucleotides, as indicated.

Pull-down assays in detergent solution yielded similar results (Fig. 5B, Left), and these experiments were also used to investigate the combined effects of substrate and nucleotides on the hiMolBC–A interaction. In the absence of nucleotides, substantial inhibition can only be observed at substrate concentrations greater than 375 μM (Fig. 5B, Left, topmost bands). This pattern is similar yet somewhat shifted toward lower substrate concentrations in the presence of ADP. In the ATP-bound state, low levels of complex formation were detected in the absence of substrate, but not in the presence of even the lowest tested MoO42– concentration. The interaction of hiMolA with the vanadate-trapped transporter could hardly be visualized even in the absence of substrate. Similar results were obtained in liposomes (Fig. 5B, Right), where the highest level of complex formation was observed in the absence of nucleotides. In the presence of nucleotides, addition of 100 μM MoO42– was sufficient to almost completely abolish the interaction between the transporter and the SBP.

The combined effects of substrate and nucleotides on the hiMolBC–A interaction were also studied by SPR experiments. In the presence of 200 μM MoO42–, the formation of a stable hiMolBC–A complex was readily detected (Fig. 5C). This substrate concentration (by itself) does not greatly affect complex formation (Fig. 2). However, combining 200 μM MoO42– with either ATP–EDTA or ATP–Mg–vanadate led to a complete inhibition of stable complex formation, much like that described above in the liposomes and pull-down experiments.

Discussion

The results presented here point to significant mechanistic differences between the two transport systems.

In the absence of nucleotides and substrate, the hiMolBC–A complex is of highest affinity and stability. Under the same conditions we could not detect formation of the afModBC–A complex. When hiMolBC is vanadate trapped (transition state) or ATP bound, its affinity to hiMolA is reduced. In contrast, the ATP-bound state and especially the transition state of afModBC have the highest affinity to afModA. In both systems, despite having opposite effects on the stability of the complex, the transition state shows the greatest effect.

In hiMolBC–A, high-substrate concentrations inhibit complex formation mainly by reducing the kon. We do not think this inhibition is related to substrate occupancy of the SBP as it only occurs at concentrations that are significantly higher than the KD of hiMolA toward its substrates. This inhibition is more likely related to an SBP-independent interaction between the substrate and the transporter (Fig. 2C), perhaps providing allosteric regulation. At concentrations that correlate to the substrate affinity of hiMolA, substrate affects the interaction only in the presence of nucleotide. Under these conditions, the combined effect of substrate binding (by the SBP) and nucleotide binding (by the transporter) drives complex dissociation.

In afModBC–A, substrate seems to have a dual role, affecting both complex formation and its dissociation. When the transporter is nucleotide free, substrate clearly has a supporting effect on complex formation. However, once the complex has formed and is now pseudostable (i.e., in the transition state), substrate contributes to its dissociation. Considering that a transport reaction is cyclic, both these effects can be viewed as supporting the progression of the transport cycle.

Mechanistic Models of Action.

From a mechanistic perspective, very little is known of hiMolBC–A and afModBC–A. Keeping this in mind, by using the kinetic constants summarized in Table 1, we propose the following tentative mechanistic models for each of the transport systems.

hiMolBC–A.

In the absence of substrate and SBP, the basal ATPase activity of hiMolBC–A is very high (3.68 μmol min−1⋅mg−1; Fig. S5A). Considering the apparent affinity of hiMolBC–A toward ATP (Km = 39 μM; Fig. S5B) and the estimated in vivo intracellular ATP concentrations, we assume at this point that the transporter constantly hydrolyzes ATP.

The SBP has the highest affinity and fastest kon toward the nucleotide-free transporter, so it is most likely that this is when the complex forms. As long as ATP is not bound and hydrolyzed, this complex is stable (koff = 8.6 × 10−4⋅s−1) and is unperturbed by a stoichiometric presence of substrate. Fig. 5C offers a snapshot of the transport cycle: In the presence of stoichiometric substrate concentrations, the SBP readily docks to the transporter and a very stable complex is formed. However, this complex falls apart as soon as ATP is bound and hydrolyzed. As the hydrolysis products are released, and the transporter is now nucleotide-free, the system is reset for the next transport cycle. In the absence of substrate, regardless of the nucleotide state of the transporter, hiMolBC–A form a stable, slowly dissociating complex. This suggests that unless substrate is around, hiMolBC–A will be found as a complex.

afModBC–A.

Unlike hiMolBC–A, yet similar to other type I ABC transporters, afModBC–A has a very low basal ATPase activity (∼25 nmol min−1⋅mg−1) (23). In type I ABC transporters, closure of the nucleotide binding domains (NBDs) and stimulation of ATP hydrolysis are triggered by docking of the SBP to the transporter. Thus, considering cellular ATP concentrations, we suggest that the resting state of afModBC is the nonhydrolyzing ATP-bound transporter. Since the transporter will not shift to its NBDs closed-dimer conformation unless the SBP docks, this state is equivalent to the nucleotide-free state in our experiments. From the data shown in Fig. 1, we propose that afModA associates with the resting state of afModBC preferentially when it is substrate loaded. This interaction has a fast kon but also a fast koff, meaning that the SBP will fall off very quickly unless ATP hydrolysis is triggered. Docking of substrate-loaded afModA to the resting transporter will result in closure of the NBDs (i.e., ATP-bound state) and ultimately ATP hydrolysis. In the ATP-bound (NBDs closed) and in the transition states, the dissociation of the complex is slowed ∼50- and ∼400-fold, respectively. Potentially, this stalling allows time for substrate to be transferred from the SBP to the transporter. Only after hydrolysis and release of ADP and Pi does the complex resume its fast koff and dissociate. This sequence of events favors coupling between ATP hydrolysis and transport, which is a feature of type I ABC transporters.

Notably, the result of energy input by ATP binding and hydrolysis is very different between the two systems: destabilizing an otherwise stable complex (hiMolBC–A) or stabilizing an intrinsically unstable complex (afModBC–A).

Implications for the Transport Mechanism of Other ATP Transporters.

The kon’s determined here for the two systems are in the same range of those we have determined for other ABC transport systems (19) and are typical for many protein–protein interactions (38, 39). Equilibrium affinities (KD) of ∼10−5 M were reported for the methionine, maltose, histidine, and oligopeptide ABC import systems (19, 21, 25, 40, 41). Since koff = KD × kon, unless the kon of these systems is extraordinarily slow (orders of magnitude slower than typically measured), their koff is in the range of 0.1–1 s−1 (i.e., fast dissociating like afModBC–A). Such fast dissociation explains why complex formation was never detected in these systems using equilibrium methods. Importantly, all five systems have been shown (23, 35, 42) or predicted to adopt a type I membrane fold (Fig. S6). In contrast, BtuCD–F and hiMolBC–A adopt a type II membrane fold (31, 43), form stable complexes (slow koff), and in both cases substrate and nucleotide reduce the affinity between the transporter and its SBP. Two other ABC transporters (HmuUV and FhuBC) with a type II fold (Fig. S6) seem to share at least some of these characteristics (32) (figures 6 and 7 in ref. 44).

Thus, the emerging theme is that the small, type I ABC import systems form low-affinity, fast-dissociating complexes. In contrast, their bigger counterparts, the type II systems form high-affinity, slowly dissociating complexes.

Materials and Methods

Protein Expression and Purification.

hiMolBC, afModBC, and BtuCD were expressed and purified essentially as previously described (23, 31, 43). For preparation of membrane fraction, cells were resuspended in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, 0.5 M NaCl, 30 μg/mL DNase (Worthington), one complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture tablet (Roche), 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, and ruptured by three passages in an EmulsiFlex-C3 homogenizer (Avestin). Membranes were pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 120,000 × g for 45 min; washed and resuspended in 50 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, 0.5 M NaCl, and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol; and stored in –80 °C until use. hiMolA and afModA were expressed as N-terminal FLAG-tag fusions in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) cells (Novagen) grown at 37 °C in M9 minimal media. hiMolA and afModA were purified by size exclusion and ion-exchange chromatography.

Reconstitution of Transporters into Liposomes.

hiMolBC, afModBC, and BtuCD were reconstituted into liposomes according to previously established protocols (19) except that 0.1% n-decyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DM) was used for hiMolBC reconstitution, and in all cases the lipid–protein ratio was 66 (W/W).

Association Assays in Proteoliposomes.

Proteoliposomes were resuspended to a final concentration of 30 mg/mL lipids in 25 mM Tris⋅HCl, 150 mM NaCl. Following three cycles of freeze/thaw, the suspension was bath-sonicated until clear. Flag-tagged hiMolA or Flag-tagged afModA was added at the indicated concentrations and tilted for 30 min. The liposome-bound and -unbound fractions were separated by ultracentrifugation at 150,000 × g for 15 min. The supernatant was removed and the pellets were rinsed and resuspended with an equal volume of buffer. The amount of Flag-tagged hiMolA or Flag-tagged afModA in each fraction was visualized by immunoblot detection, using an anti-Flag antibody (Sigma).

Association Assays in Detergent Solution.

His-tagged transporters were immobilized onto Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) beads (Qiagen) as previously described (19). After 10 min incubation with the indicated concentrations of Flag-tagged SBPs, two washing cycles were used to remove unbound material. Bound proteins were eluted in a single step with buffer containing 1 M imidazole. The amount of Flag-tagged protein in each fraction was visualized by immunoblot detection, using an anti-Flag antibody (Sigma).

SPR Measurements.

All measurements were performed using a Biacore T200 (GE). Before immobilization, transporters were subjected to size exclusion chromatography to remove any trace of aggregation. Both hiMolBC afModBC could be immobilized directly onto series-S Ni-NTA biosensor chips or onto CM-5 chips using standard amine chemistry. Results from both methods were highly similar. Biosensor chips were used only for 3–4 experiments as significant bulk responses quickly developed. The running buffer contained 25 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% DM (Affymetrix) for hiMolBC, or 0.05% n-dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM, Affymetrix) for afModBC. To reduce nonspecific interactions (mostly experiments with afModBC), 0.1 mg/mL BSA was added to the running buffer and BtuCD was immobilized on the reference cell. Unless otherwise stated, surface densities were ∼0.12–0.3 ng/mm2 (1200∼3000 Ru for a 150–180 kDa mixed protein-detergent micelle). All injections were performed at least as duplicates in random order and double-referenced. For regeneration of hiMolBC, we used a 2-min injection of 1.25 M MgCl2, 0.3% DM, 25 mM Tris⋅HCl pH 7.5, and 150 mM NaCl. Data analysis was performed using Biacore’s standard evaluation software, and a simple 1:1 Langmuir interaction model was used for fitting and for derivation of kinetic rate constants. Mass transport effects were not observed in flow rates of up to 75 μL/min, and the reactions were thus concluded to follow pseudo–first-order kinetics.

Three-Dimensional Structure Modeling.

Modeling of the transmembrane domains of HisM, OppB, and FhuB was performed using the SWISS-MODEL server without specifying a template (automated mode).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kaspar Locher for kindly providing the plasmids encoding afModBC–A and Heather Pinkett for fruitful discussions. We also thank Orly Tabachnikov and Yuval Shoham for their help with the isothermal calorimetry experiments. This work was supported in part by grants from the Israeli Academy of Sciences, the Mallat family research foundation, and by the European Research Council FP-7 International Reintegration Grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1213598110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ambudkar SV, Kimchi-Sarfaty C, Sauna ZE, Gottesman MM. P-glycoprotein: from genomics to mechanism. Oncogene. 2003;22(47):7468–7485. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ames GF, Mimura CS, Holbrook SR, Shyamala V. Traffic ATPases: A superfamily of transport proteins operating from Escherichia coli to humans. Adv Enzymol Relat Areas Mol Biol. 1992;65:1–47. doi: 10.1002/9780470123119.ch1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dassa E, Bouige P. The ABC of ABCS: A phylogenetic and functional classification of ABC systems in living organisms. Res Microbiol. 2001;152(3-4):211–229. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01194-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davidson AL, Dassa E, Orelle C, Chen J. Structure, function, and evolution of bacterial ATP-binding cassette systems. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2008;72(2):317–364. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00031-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins CF. ABC transporters: From microorganisms to man. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1992;8:67–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.08.110192.000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins CF. ABC transporters: Physiology, structure and mechanism—An overview. Res Microbiol. 2001;152(3-4):205–210. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holland IB, Cole SPC, Kuchler K, Higgins CF, editors. ABC Proteins: From Bacteria to Man. London: Academic; 2003. p. 647. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Møller SG, Kunkel T, Chua N-H. A plastidic ABC protein involved in intercompartmental communication of light signaling. Genes Dev. 2001;15(1):90–103. doi: 10.1101/gad.850101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paytubi S, et al. ABC50 promotes translation initiation in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(36):24061–24073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.031625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt KL, et al. A predicted ABC transporter, FtsEX, is needed for cell division in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(3):785–793. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.3.785-793.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doeven MK, Kok J, Poolman B. Specificity and selectivity determinants of peptide transport in Lactococcus lactis and other microorganisms. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57(3):640–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higgins CF, Linton KJ. The ATP switch model for ABC transporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11(10):918–926. doi: 10.1038/nsmb836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Locher KP. Structure and mechanism of ABC transporters. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14(4):426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu G, Westbrooks JM, Davidson AL, Chen J. ATP hydrolysis is required to reset the ATP-binding cassette dimer into the resting-state conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(50):17969–17974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506039102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rees DC, Johnson E, Lewinson O. ABC transporters: The power to change. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(3):218–227. doi: 10.1038/nrm2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borths EL, Poolman B, Hvorup RN, Locher KP, Rees DC. In vitro functional characterization of BtuCD-F, the Escherichia coli ABC transporter for vitamin B12 uptake. Biochemistry. 2005;44(49):16301–16309. doi: 10.1021/bi0513103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goetz BA, Perozo E, Locher KP. Distinct gate conformations of the ABC transporter BtuCD revealed by electron spin resonance spectroscopy and chemical cross-linking. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(2):266–270. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joseph B, Jeschke G, Goetz BA, Locher KP, Bordignon E. Transmembrane gate movements in the type II ATP-binding cassette (ABC) importer BtuCD-F during nucleotide cycle. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(47):41008–41017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.269472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewinson O, Lee AT, Locher KP, Rees DC. A distinct mechanism for the ABC transporter BtuCD-BtuF revealed by the dynamics of complex formation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17(3):332–338. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weng J, Fan K, Wang W. The conformational transition pathways of ATP-binding cassette transporter BtuCD revealed by targeted molecular dynamics simulation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(1):e30465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson AL, Shuman HA, Nikaido H. Mechanism of maltose transport in Escherichia coli: Transmembrane signaling by periplasmic binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(6):2360–2364. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tirado-Lee L, Lee A, Rees DC, Pinkett HW. Classification of a Haemophilus influenzae ABC transporter HI1470/71 through its cognate molybdate periplasmic binding protein, MolA. Structure. 2011;19(11):1701–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hollenstein K, Frei DC, Locher KP. Structure of an ABC transporter in complex with its binding protein. Nature. 2007;446(7132):213–216. doi: 10.1038/nature05626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J, Sharma S, Quiocho FA, Davidson AL. Trapping the transition state of an ATP-binding cassette transporter: Evidence for a concerted mechanism of maltose transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(4):1525–1530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041542498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dean DA, Hor LI, Shuman HA, Nikaido H. Interaction between maltose-binding protein and the membrane-associated maltose transporter complex in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6(15):2033–2040. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doeven MK, Abele R, Tampé R, Poolman B. The binding specificity of OppA determines the selectivity of the oligopeptide ATP-binding cassette transporter. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(31):32301–32307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404343200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khare D, Oldham ML, Orelle C, Davidson AL, Chen J. Alternating access in maltose transporter mediated by rigid-body rotations. Mol Cell. 2009;33(4):528–536. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu CE, Liu P-Q, Ames GF-L. Characterization of the adenosine triphosphatase activity of the periplasmic histidine permease, a traffic ATPase (ABC transporter) J Biol Chem. 1997;272(35):21883–21891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orelle C, Ayvaz T, Everly RM, Klug CS, Davidson AL. Both maltose-binding protein and ATP are required for nucleotide-binding domain closure in the intact maltose ABC transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(35):12837–12842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803799105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patzlaff JS, van der Heide T, Poolman B. The ATP/substrate stoichiometry of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter OpuA. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(32):29546–29551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304796200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinkett HW, Lee AT, Lum P, Locher KP, Rees DC. An inward-facing conformation of a putative metal-chelate-type ABC transporter. Science. 2007;315(5810):373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.1133488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woo J-S, Zeltina A, Goetz BA, Locher KP. X-ray structure of the Yersinia pestis heme transporter HmuUV. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(12):1310–1315. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Locher KP. Structure and mechanism of ATP-binding cassette transporters. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364(1514):239–245. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hvorup RN, et al. Asymmetry in the structure of the ABC transporter-binding protein complex BtuCD-BtuF. Science. 2007;317(5843):1387–1390. doi: 10.1126/science.1145950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oldham ML, Khare D, Quiocho FA, Davidson AL, Chen J. Crystal structure of a catalytic intermediate of the maltose transporter. Nature. 2007;450(7169):515–521. doi: 10.1038/nature06264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berntsson RP, Smits SH, Schmitt L, Slotboom DJ, Poolman B. A structural classification of substrate-binding proteins. FEBS Lett. 2010;584(12):2606–2617. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levy S, Kafri M, Carmi M, Barkai N. The competitive advantage of a dual-transporter system. Science. 2011;334(6061):1408–1412. doi: 10.1126/science.1207154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schlosshauer M, Baker D. Realistic protein-protein association rates from a simple diffusional model neglecting long-range interactions, free energy barriers, and landscape ruggedness. Protein Sci. 2004;13(6):1660–1669. doi: 10.1110/ps.03517304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schreiber G. Kinetic studies of protein-protein interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ames GF-L, Liu CE, Joshi AK, Nikaido K. Liganded and unliganded receptors interact with equal affinity with the membrane complex of periplasmic permeases, a subfamily of traffic ATPases. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(24):14264–14270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.24.14264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doeven MK, van den Bogaart G, Krasnikov V, Poolman B. Probing receptor-translocator interactions in the oligopeptide ABC transporter by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2008;94(10):3956–3965. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.120964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kadaba NS, Kaiser JT, Johnson E, Lee A, Rees DC. The high-affinity E. coli methionine ABC transporter: Structure and allosteric regulation. Science. 2008;321(5886):250–253. doi: 10.1126/science.1157987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Locher KP, Lee AT, Rees DC. The E. coli BtuCD structure: A framework for ABC transporter architecture and mechanism. Science. 2002;296(5570):1091–1098. doi: 10.1126/science.1071142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rohrbach MR, Braun V, Köster W. Ferrichrome transport in Escherichia coli K-12: Altered substrate specificity of mutated periplasmic FhuD and interaction of FhuD with the integral membrane protein FhuB. J Bacteriol. 1995;177(24):7186–7193. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7186-7193.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.