Abstract

Human enterovirus 71 is a picornavirus causing hand, foot, and mouth disease that may progress to fatal encephalitis in infants and small children. As of now, no cure is available for enterovirus 71 infections. Small molecule inhibitors binding into a hydrophobic pocket within capsid viral protein 1 were previously shown to effectively limit infectivity of many picornaviruses. Here we report a 3.2-Å-resolution X-ray structure of the enterovirus 71 virion complexed with the capsid-binding inhibitor WIN 51711. The inhibitor replaced the natural pocket factor within the viral protein 1 pocket without inducing any detectable rearrangements in the structure of the capsid. Furthermore, we show that the compound stabilizes enterovirus 71 virions and limits its infectivity, probably through restricting dynamics of the capsid necessary for genome release. Thus, our results provide a structural basis for development of antienterovirus 71 capsid-binding drugs.

Keywords: stability, virus

Human enterovirus 71 (EV71) is a picornavirus associated with hand, foot, and mouth disease (1). Nevertheless, EV71 infections may progress to severe encephalitis that causes various types of neurological complications including polio-like paralysis. Furthermore, the infection may be fatal for infants and young children (2). EV71 outbreaks are reported throughout the world, but have been especially severe in the Asia-Pacific region.

Picornaviruses are small, icosahedral, nonenveloped animal viruses with positive sense RNA genomes. Picornavirus capsids have pseudo T = 3 symmetry with 60 copies of each of four viral proteins—VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4—that form an ∼300 Å diameter icosahedral shell. The surface of a picornavirus capsid is formed by subunits VP1, VP2, and VP3 that each has a β-sandwich jelly roll fold, whereas VP4 is a small protein attached to the inner surface of the capsid. There is a circular depression or “canyon” around each icosahedral fivefold axis of symmetry on the surface of many picornaviruses (3, 4). The EV71 canyon is shallower than that in polioviruses and rhinoviruses (5, 6).

Receptors with an Ig-like fold have been shown to bind into the canyon (7–13). When receptor molecules bind into the canyon, they dislodge a “pocket factor” from a pocket within VP1 immediately below the floor of the canyon. The shape of the pocket factor and the hydrophobic environment of the pocket suggest that the pocket factor is probably a lipid (14–17). Analysis of lipid molecules extracted from virions of bovine enterovirus had shown that the pocket factor is not a single type of molecule but rather a mixture of lipids with the most represented molecules being palmitic acid and myristic acid (15). When a receptor binds into the canyon, it depresses the floor of the canyon corresponding to the roof of the pocket. Similarly, when a lipid or antiviral compound binds into the pocket, it expands the roof of the pocket, corresponding to the floor of the canyon (14, 17). Thus, canyon-binding receptors and the pocket factor compete with each other for binding to the virion. Nevertheless, not all receptors of picornaviruses bind into the canyon. A minor group of human rhinoviruses (HRV) bind to low-density lipoprotein receptors (18, 19), whereas Coxsackie and echoviruses use decay-accelerating factor as a cellular receptor (20, 21). Scavenger receptor B2 (22), sialylated glycans (23), and P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (24–26) were shown to function as possible receptors for EV71.

Capsids of numerous picornaviruses such as most HRVs, polioviruses, and EV71 contain a pocket factor that plays an essential role in regulating particle stability (14, 27). The release of the pocket factor, induced by receptor binding, leads to particle destabilization, externalization of VP4 and the N-termini of the VP1 subunits, and subsequently to genome release. Therefore, the presence of the pocket factor functions as a switch in initiating picornavirus infection. Some rhinoviruses such as HRV14 and HRV3 lack a pocket factor, when crystallized (3, 28). Although it has been suggested that the pocket factor might be an artifact of the purification procedure (29) it is improbable that the VP1 pocket is a purely accidental feature of picornavirus capsids, as compounds that bind into the pocket are capable of regulating the virus stability and infectivity (30). Small molecule inhibitors that bind into the hydrophobic pocket within subunit VP1 can inhibit viruses irrespective of whether they contain a pocket factor in the native state or not (14). In the case of viruses containing the pocket factor, the inhibitor competes with the putative lipid molecule for binding to the virus. For viruses that lack the pocket factor, the binding of the inhibitor induces a conformational change in the capsid protein VP1 resulting in an opening of the hydrophobic cavity between the two β-sheets of the jelly roll fold (31, 32).

Small molecules that bind into the hydrophobic pocket within VP1 were shown to be potent inhibitors of many picornaviruses including rhinoviruses (31), Coxsackie viruses A and B (17, 33), and polioviruses (12, 16). The inhibitors bind into the hydrophobic pocket within VP1 with high affinity and therefore cannot be dislodged upon receptor binding. Several putative capsid-binding inhibitors of EV71 were synthesized and shown to be effective (34, 35), but molecular details of their interactions with the capsid proteins were not known.

Although the disease caused by EV71 is a public health threat, no vaccines or antiviral compounds are currently available. Here we present the crystal structure of EV71 virions in complex with the capsid-binding inhibitor WIN 51711 at 3.2 Å resolution. Furthermore, we show that the compound can limit EV71 infection.

Results and Discussion

WIN 51711 Limits EV71 Infectivity and Stabilizes Virions.

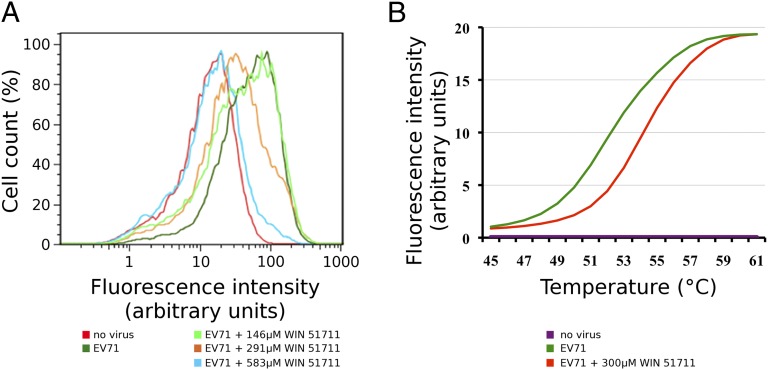

WIN 51711 had previously been shown to be an inhibitor of rhinoviruses and polioviruses (31, 36). Using FACS assay, we have now shown that the EV71 infectivity is inhibited by 600 μM WIN 51711 (Fig. 1A). The decrease in infectivity of EV71 when treated with WIN 51711 results in an increase of the virion to plaque-forming unit ratio. Furthermore, the RNA genome in EV71 virions incubated with 300 μM WIN 51711 was less accessible to RNA binding fluorescent dyes Sybr green I and II than genome of native virions (Fig. 1B). The virions stabilized by WIN 51711 had to be heated 3 °C higher than native virions to obtain equal staining of the genome. It is therefore likely that the mechanism of inhibition is due to the stabilizing effect of WIN 51711 on the EV71 capsid, thereby preventing uncoating of the virion.

Fig. 1.

Impact of WIN 51711 on EV71 infectivity and virion stability. (A) FACS analysis of EV71 infectivity. Cells were infected with EV71 in the presence or absence of varying concentrations of WIN 51711 for 30 h and were then fixed and stained with an anti-EV71 antibody and fluorescein-conjugated secondary antibody. The graph shows distribution of fluorescence intensities in the respective cell populations. (B) Sybr green fluorescent assay to measure stability of EV71 particles. EV71 virions were mixed with Sybr green dyes I and II and heated to indicated temperatures. The fluorescent signal increases as the dye binds to RNA that is release from thermally destabilized particles. Green line, EV71 virions; red line, EV71 with 300 μM WIN 51711; purple line, control without virus. See Materials and Methods for details.

X-Ray Structures of Native EV71 Virion and Its Complex with WIN 51711.

The crystal structure of EV71 strain MY104-9-SAR-97 (GenBank DQ341368.1) was determined to 2.7 Å resolution. Structures of the EV71-WIN 51711 complex were determined independently from two datasets that included data to 3.2 Å and 3.4 Å resolution. The maps resulting from 20-fold noncrystallographic averaging showed clear features of amino acid side chains and of carbonyl oxygens. Models of the capsid proteins VP1, VP2, VP3, and VP4 were built except for residues 1 and 298 of VP1, 1–9 of VP2, and 1–12 of VP4. Had it been calculated, crystallographic Rfree would have been similar to crystallographic Rwork, because of the high 20-fold noncrystallographic symmetry (37, 38). Therefore, all measured reflections were used in the structure refinement (Table 1). The structure of the icosahedral asymmetric unit of EV71 consists of 840-aa residues. Nine additional residues (135–143) of the VP2 “puff” loop exposed on the particle surface were visible in the electron density map in comparison with the previously determined EV71 I212121 structure [Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 4AED]. The rmsd between the positions of Cα atoms in the current and previously determined EV71 structures were between 0.2 and 0.5 Å.

Table 1.

Scaling and refinement statistics

| Structure |

|||

| EV71 native | EV71 WIN 51711 3.4Å | EV71 WIN 51711 3.2Å | |

| Space group | I23 | I23 | I23 |

| Unit cell dimensions, Å | 594.5 | 591.0 | 592.5 |

| Resolution limits (high-resolution bin), Å | 30.4–2.7 (2.82–2.70) | 27.5–3.4 (3.55–3.40) | 33.2–3.2 (3.35–3.20) |

| Completeness, % | 74.9 (35.9) | 53.3 (27.5) | 66.8 (44.0) |

| Rmerge* | 0.208 (0.709) | 0.251 (0.538) | 0.332 (0.974) |

| Average redundancy | 1.9 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.5) | 2.5 (2.2) |

| <I>/<σI> | 3.05 (0.56) | 2.60 (1.06) | 2.50 (0.81) |

| Reciprocal space correlation coefficient of Fobs and Fcalc after convergence of map | 0.904 | 0.830 | 0.839 |

| R-factor | 0.240 (0.410) | 0.243 (0.344) | 0.249 (0.355) |

| Average B-factor | 31.0 | 30.6 | 36.9 |

| Ramachandran plot outliers, %† | 0.24 | 1.92 | 1.56 |

| Ramachandran plot most favored regions, %† | 95.43 | 89.54 | 89.66 |

| Rotamer outliers, %† | 1.83 | 4.77 | 5.61 |

| rmsd, bonds, Å | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.008 |

| rmsd, angles, ° | 1.29 | 1.49 | 1.49 |

| N of unique reflections | 692,970 (34,593) | 247,559 (12,721) | 353,681 (15,538) |

Fcalc, structure factor amplitudes calculated by Fourier inversion of averaged electron density map; Fobs, observed structure factor amplitudes. Values in parentheses represent high resolution bin.

.

.

According to the criterion of Molprobity.

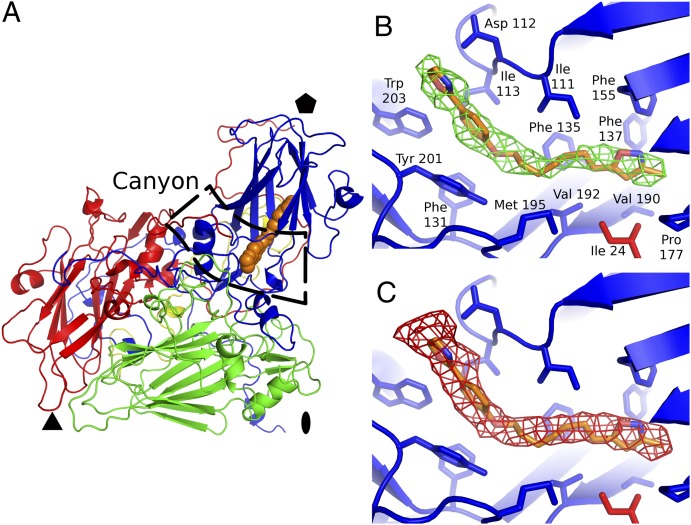

Shih et al. have identified a single residue mutation, Val192-Met, that confers resistance to the presumed capsid binding inhibitor BPR0Z-194 (39). Val192 is located in the middle of the wild type VP1 pocket (Fig. 2B). It is therefore likely that the substitution for methionine, a residue with larger side chain, prevents binding of BPR0Z-194 to the capsid. This observation verifies the role of VP1 pocket for the infectivity of the virus.

Fig. 2.

Binding of native pocket factor and WIN 51711 into the VP1 pocket. (A) Overview of EV71 protomer with capsid protein subunits VP1 (blue), VP2 (red), VP3 (green), and VP4 (yellow) shown in a cartoon representation. WIN 51711 is shown as a space-filling model in orange. Positions of the icosahedral symmetry elements are indicated. (B) WIN 51711 electron density (green), with WIN 51711 model shown in orange. VP1 is shown in cartoon representation in blue with side chains of residues forming the hydrophobic pocket shown as sticks. Side chain of Leu-24 of VP3 that forms the bottom of the pocket is shown in red. (C) Electron density of the native pocket factor (red). Superimposed WIN 51711 model is shown for comparison.

Comparison of WIN 51711 with the Native Pocket Factor.

The major difference between the native EV71 and the EV71-WIN 51711 complex is that the native pocket factor density extends ∼2 Å further toward the opening of the pocket into the canyon than the WIN 51711 density (Fig. 2). To evaluate differences in the shape of the pocket factor and WIN 51711 density, real-space correlation coefficients (RSCC) were calculated to compare the electron density distributions within the VP1 pocket of the native and inhibitor complexes. The experimental electron density maps were calculated with phases obtained by phase extension starting from 10 Å resolution and are therefore free of model bias. The RSCCs comparing electron density distributions of pocket factor to WIN 51711 are less than 0.77, whereas RSCCs comparing different datasets of the same object are greater than 0.89 (Table 2). The RSCCs comparing experimental electron density maps with those derived from models were calculated to verify the nature of the moiety in the pocket (Table 3). For crystals soaked with WIN 51711, the density within the pocket correlates better with structure of WIN 51711 than with sphingosine that was used to model the pocket factor in the native structure of EV71 (6). Similarly, in the native crystals, the electron density within the pocket agrees better with the sphingosine model. Thus, WIN 51711 replaced the pocket factor in crystals cocrystallized with the inhibitor. Nevertheless, it is possible that WIN 51711 did not replace all pocket factor molecules and that the observed electron density represents an average between the pocket factor and WIN 51711.

Table 2.

RSCC comparison of electron densities within VP1 pockets of native and WIN 51711–derivative EV71 structures

| Structure | Native 3VBF | EV71 native | WIN 51711 3.2Å | WIN 51711 3.4Å |

| WIN 51711 3.4Å | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.91 | — |

| WIN 51711 3.2Å | 0.77 | 0.73 | — | |

| EV71 native | 0.89 | — | ||

| Native-3VBF | — |

Numbers in bold indicate that the compared electron density maps correspond to the same compound. A dash indicates a comparison is meaningless as the structures are identical.

Table 3.

RSCC comparison of experimental electron densities within VP1 pocket with electron densities derived from refined models

| Structure | Pocket factor model | RSCC |

| WIN 51711 3.2 Å | WIN 51711–2OUT* | 0.85 |

| WIN 51711–2IN† | 0.82 | |

| Sphingosine | 0.61 | |

| WIN 51711 3.4 Å | WIN 51711–2OUT* | 0.80 |

| WIN 51711–2IN† | 0.78 | |

| Sphingosine | 0.77 | |

| EV71 native | WIN 51711–2OUT* | 0.80 |

| Sphingosine | 0.87 | |

| EV71 native 3VBF | WIN 51711–2OUT* | 0.80 |

| Sphingosine | 0.92 | |

| HRV14 | WIN 51711–2OUT* | 0.82 |

| WIN 51711–2IN† | 0.80 |

Orientation of the WIN51711 compound in the VP1 pocket in which the end of the molecule that contains two aromatic rings points toward the opening of the pocket.

Orientation of the WIN51711 compound in the VP1 pocket in which the end of the molecule that contains single aromatic ring points toward the opening of the pocket.

The molecule of WIN 51711 is elongated in shape with two aromatic rings at one end and one ring at the other (Fig. 2B). The RSCC comparison of simulated electron density maps of WIN 51711 molecules refined in the two alternative orientations within the VP1 pocket shows that both orientations fit well into the experimental density, with slight preference for the orientation of the inhibitor with the two rings pointing toward the opening of the pocket (Table 3, Fig. 2B). Comparable ambiguity in determining the orientation of WIN 51711 was encountered in its complex with HRV 14 (31, 40). Similar to the situation in EV71, the RSCC analysis of the two possible orientations of WIN 51711 within the pocket of HRV 14 indicates a slight preference for the two rings pointing toward the opening of the pocket (Table 3).

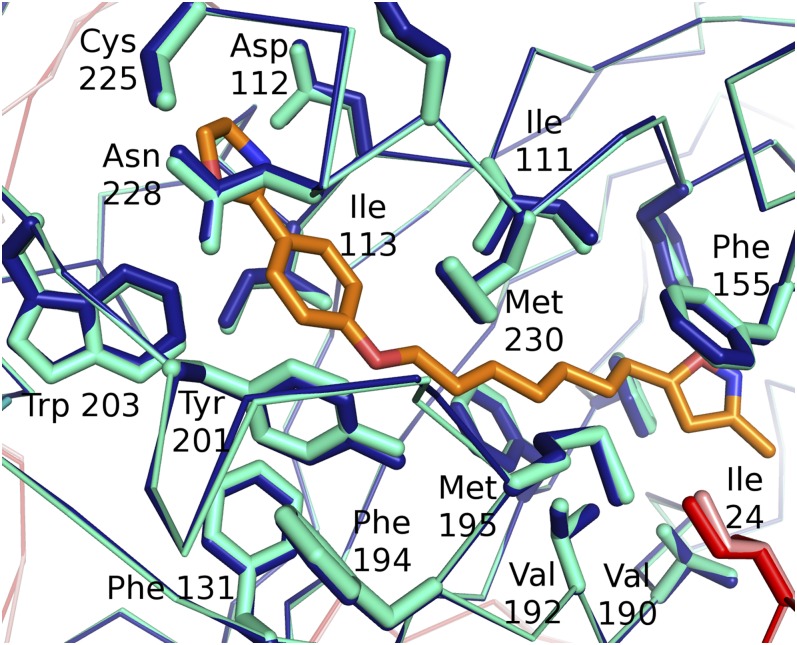

Structure of Residues Forming the VP1 Pocket.

The RMSD comparison of positions of residues that form the pocket in the native and the two WIN 51711–containing complexes (Table 4) shows that there are no major rearrangements induced by WIN 51711 binding within the pocket (Fig. 3). The inhibitor interacts mostly with hydrophobic side chains of residues forming the interior of the pocket. Similarly, changes in the structure of HRV16, where the inhibitors replaced the pocket factor, were quite minor (41). In contrast, binding of WIN 51711 to the collapsed pocket of HRV14 induced conformational changes within VP1 (31).

Table 4.

rmsd of residues forming the hydrophobic pocket

| Structure | WIN 51711 3.2Å | WIN 51711 3.4Å | EV71 native |

| EV71 native | 0.159 | 0.189 | — |

| WIN 51711 3.4 Å | 0.139 | — | |

| WIN 51711 3.2 Å | — |

rmsd of residues that have at least one atom closer than 4.0 Å to any atom of WIN 51711. The program O (48) was used for superposition of the residues. A dash indicates a comparison is meaningless as the structures are identical.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the positions of side chains of residues forming the VP1 hydrophobic pocket in the WIN 51711 complex (dark blue) and native structure (light blue). Main-chain trace of protein subunits is shown as ribbon and side chains of residues forming the pocket are shown as sticks. VP1, blue; VP3, red. WIN 51711 is shown as a stick model in orange.

Design of EV71 Capsid-Binding Inhibitors.

Our results show the molecular details of the WIN 51711 interactions with EV71. Thus, WIN 51711 can be used as a scaffold for further development of more potent inhibitors. For example, extra groups added to the five-membered oxazoline ring might interact with polar residues that form the opening of the pocket into the canyon. Considering that EV71 receptors probably do not bind into the shallow EV71 canyon (22, 24), the EV71 pocket factor may function merely to stabilize the particle and not as a switch regulating genome release as in rhinoviruses, polioviruses, and Coxsackie viruses. Therefore, the critical property of future EV71 capsid-binding inhibitors is their ability to stabilize the virus.

Materials and Methods

EV71 Preparation, Crystallization, and Diffraction Data Collection.

EV71 was produced and purified as described previously (42). Crystals of EV71 were obtained using the hanging drop technique with conditions analogous to those described by Wang et al. (6). The crystallization drops were prepared by mixing 0.83 µL EV71 at ∼2 mg/mL in PBS with 0.17 µL 0.2 M sodium citrate, 0.1 M Tris pH 8.5, and 30% (vol/vol) PEG 400. The well solution contained 1.8 M sodium acetate and 0.1 M Bis-Tris propane, pH 7.0. Crystals formed within 1 wk. The crystals of EV71 WIN 51711 complex were prepared in the same way except that the virus solution included 2% (vol/vol) dimethyl sulfoxide and 0.1 mg/mL WIN 51711. For data collection, crystals were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. The crystallization solution was a sufficient cryoprotectant. Each dataset was collected from a single crystal at 100 K on the ADSC 315 detector at beamline 14 C BioCARS at the Advanced Photon Source synchrotron. An oscillation range of 0.2° was used during data collection. The diffraction images were processed and scaled using the HKL2000 package (43) (Table 1).

X-Ray Structure Determination.

Virions of EV71 crystallized in the body-centered cubic space group I23. The cell parameters differed from crystal to crystal by up to 5 Å (Table 1). The crystallographic asymmetric unit contained one-third of a virion. The orientation of the virion about the crystallographic threefold axes was determined with a one-dimensional locked-rotation function search using the program GLRF (44). Orientations of the particles in different crystals differed by up to 2°. The differences in particle orientation could be correlated with differences in the unit cell parameters among individual crystals. Position of the particle center was determined with a one-dimensional translation function search using the program Phaser (45). Initial phases up to 10 Å resolution were calculated from a properly oriented and positioned model of EV71 (PDB ID code 4AED) with the program CNS (46). The atoms corresponding to the pocket factor were removed from the model before the phase calculation. The phases were refined with 10 cycles of 20-fold real-space noncrystallographic symmetry averaging with the program AVE (47). The mask defining the volume of electron density to be averaged was derived from the EV71 atomic model by including all grid points within 5 Å of each atom. Grid points outside the capsid were set to the average value of the density outside the mask. Phase information for reflections immediately outside the current resolution limit was obtained by extending the resolution in steps of (1/a) Å−1 followed by three cycles of averaging. This procedure was repeated until the high-resolution limit of the available data was reached. For each of the data sets, the particle orientation and position were refined by searching for their best value as judged by the correlation coefficient between observed and calculated structure amplitudes.

The structure was built manually using the program O (48) starting from the native EV71 structure. Subsequently, the structure was subjected to coordinate and B-factor refinement using the program CNS. The refinement used noncrystallographic symmetry constraints. Other calculations used the CCP4 suite of programs (49).

Data Deposition.

The EV71 native and inhibitor complex coordinates together with the observed structure amplitudes and phases derived by the phase extension have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID codes 3ZFE, 3ZFF, and 3ZFG).

FACS Infectivity Assay.

The impact of WIN 51711 on the infectivity of EV71 was determined using a FACS assay. Approximately 1 × 106 pfu of EV71 were incubated with varying concentrations of WIN51711 at 37 °C for 30 min. The virus and compound mixture was then adsorbed onto rhabdomyosarcoma cells for 1 h at room temperature and overlaid with liquid media (MEM + 10% FCS) containing the same concentrations of compound. Following incubation at 37 °C for 30 h, the cells were trypsinized and equal numbers of cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde, permeabilized with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100 and blocked with PBS + 10 mg/mL BSA (FACS buffer). The cells were then stained with an anti-EV71 monoclonal antibody (EV20/5/A5-3/C10/C1, provided by MAb Explorations) and an FITC-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody for 30 min at 4 °C with extensive washing with FACS buffer between antibody incubations. The cells were then analyzed using a Beckman Coulter FC500 flow cytometer.

Thermal Stability Assay.

Virions of EV71 (final concentration 0.125 mg/mL) were mixed with WIN 51711 (final concentration 0.01 mg/mL) in NaCl-Tris-EDTA buffer (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 120 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA) and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Sybr green I and Sybr green II dyes (Life Technologies) were added at 3× concentration (according to the manufacturer’s information) together with ANTI-RNase (ambion) at 1 U/μL final concentration. The Sybr green dyes were previously shown not to penetrate into native poliovirus virions (50). The Sybr green fluorescence of the mixture was then analyzed in a real-time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems 7300). The mixture was heated to temperatures in the range of 37–90 °C in 1-°C steps. After heating to a given temperature for 2 min, the mixture was cooled to 36 °C for 2 min, during which the fluorescence could be measured. This was necessary because interaction of Sybr green dyes with RNA is temperature-dependent.

Calculation of RSCCs.

RSCCs comparing two experimental maps or comparing an experimental map with a map calculated from a refined model were calculated using the program MAPMAN from the USF package (47). The experimental maps were calculated using phases derived from phase extension as described previously. The model-derived maps were calculated with the CNS program (46). The RSCC calculation included all grid points within 1.5Å of any atom of a given residue (∼320 grid points were used for WIN 51711 and sphingosine molecules).

Acknowledgments

We thank Vukica Srajer, Robert Henning, and the other staff of the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne National Laboratory) BioCARS beamline 14, and Robert Fischetti of GM/CA beamline 23 for help with data collection. Use of BioCARS Sector 14 was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources (NIH/NCRR) Grant RR007707. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. The authors acknowledge the use of the Flow Cytometry and Cell Separation Facility of the Bindley Bioscience Center at Purdue University (supported by NIH/NCRR Grant RR025761). This study was supported by NIH Grant AI11219 (to M.G.R.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The EV71 native and inhibitor complex coordinates, observed structure amplitudes, and phases derived by the phase extension have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 3ZFE, 3ZFF, and 3ZFG).

References

- 1.Chan LG, et al. For the Outbreak Study Group Deaths of children during an outbreak of hand, foot, and mouth disease in Sarawak, Malaysia: clinical and pathological characteristics of the disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(3):678–683. doi: 10.1086/314032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexander JP, Jr, Baden L, Pallansch MA, Anderson LJ. Enterovirus 71 infections and neurologic disease—United States, 1977-1991. J Infect Dis. 1994;169(4):905–908. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.4.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rossmann MG, et al. Structure of a human common cold virus and functional relationship to other picornaviruses. Nature. 1985;317(6033):145–153. doi: 10.1038/317145a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossmann MG. The canyon hypothesis. Hiding the host cell receptor attachment site on a viral surface from immune surveillance. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(25):14587–14590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plevka P, Perera R, Cardosa J, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. Crystal structure of human enterovirus 71. Science. 2012;336(6086):1274. doi: 10.1126/science.1218713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X, et al. A sensor-adaptor mechanism for enterovirus uncoating from structures of EV71. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(4):424–429. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belnap DM, et al. Three-dimensional structure of poliovirus receptor bound to poliovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(1):73–78. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colonno RJ, et al. Evidence for the direct involvement of the rhinovirus canyon in receptor binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85(15):5449–5453. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olson NH, et al. Structure of a human rhinovirus complexed with its receptor molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(2):507–511. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He Y, et al. Interaction of the poliovirus receptor with poliovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(1):79–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He Y, et al. Complexes of poliovirus serotypes with their common cellular receptor, CD155. J Virol. 2003;77(8):4827–4835. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4827-4835.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang P, et al. Crystal structure of CD155 and electron microscopic studies of its complexes with polioviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(47):18284–18289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807848105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xing L, et al. Distinct cellular receptor interactions in poliovirus and rhinoviruses. EMBO J. 2000;19(6):1207–1216. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.6.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rossmann MG. Viral cell recognition and entry. Protein Sci. 1994;3(10):1712–1725. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560031010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smyth M, Pettitt T, Symonds A, Martin J. Identification of the pocket factors in a picornavirus. Arch Virol. 2003;148(6):1225–1233. doi: 10.1007/s00705-002-0974-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filman DJ, et al. Structural factors that control conformational transitions and serotype specificity in type 3 poliovirus. EMBO J. 1989;8(5):1567–1579. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muckelbauer JK, et al. The structure of coxsackievirus B3 at 3.5 Å resolution. Structure. 1995;3(7):653–667. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hofer F, et al. Members of the low density lipoprotein receptor family mediate cell entry of a minor-group common cold virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(5):1839–1842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Querol-Audí J, et al. Minor group human rhinovirus-receptor interactions: Geometry of multimodular attachment and basis of recognition. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(1):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarkson NA, et al. Characterization of the echovirus 7 receptor: Domains of CD55 critical for virus binding. J Virol. 1995;69(9):5497–5501. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5497-5501.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lea SM, et al. Determination of the affinity and kinetic constants for the interaction between the human virus echovirus 11 and its cellular receptor, CD55. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(46):30443–30447. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamayoshi S, et al. Scavenger receptor B2 is a cellular receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat Med. 2009;15(7):798–801. doi: 10.1038/nm.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang B, Chuang H, Yang KD. Sialylated glycans as receptor and inhibitor of enterovirus 71 infection to DLD-1 intestinal cells. Virol J. 2009;6:141. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyamura K, Nishimura Y, Abo M, Wakita T, Shimizu H. Adaptive mutations in the genomes of enterovirus 71 strains following infection of mouse cells expressing human P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1. J Gen Virol. 2011;92(Pt 2):287–291. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.022418-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishimura Y, et al. Human P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 is a functional receptor for enterovirus 71. Nat Med. 2009;15(7):794–797. doi: 10.1038/nm.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishimura Y, Wakita T, Shimizu H. Tyrosine sulfation of the amino terminus of PSGL-1 is critical for enterovirus 71 infection. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(11):e1001174. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossmann MG, He Y, Kuhn RJ. Picornavirus-receptor interactions. Trends Microbiol. 2002;10(7):324–331. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(02)02383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao R, et al. Human rhinovirus 3 at 3.0 Å resolution. Structure. 1996;4(10):1205–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katpally U, Smith TJ. Pocket factors are unlikely to play a major role in the life cycle of human rhinovirus. J Virol. 2007;81(12):6307–6315. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00441-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant RA, et al. Structures of poliovirus complexes with anti-viral drugs: implications for viral stability and drug design. Curr Biol. 1994;4(9):784–797. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith TJ, et al. The site of attachment in human rhinovirus 14 for antiviral agents that inhibit uncoating. Science. 1986;233(4770):1286–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.3018924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chapman MS, Rossmann MG. Comparison of surface properties of picornaviruses: Strategies for hiding the receptor site from immune surveillance. Virology. 1993;195(2):745–756. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao C, et al. The crystal structure of coxsackievirus A21 and its interaction with ICAM-1. Structure. 2005;13(7):1019–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang CS, et al. Design, synthesis, and antipicornavirus activity of 1-[5-(4-arylphenoxy)alkyl]-3-pyridin-4-ylimidazolidin-2-one derivatives. J Med Chem. 2005;48(10):3522–3535. doi: 10.1021/jm050033v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shia KS, et al. Design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationship of pyridyl imidazolidinones: A novel class of potent and selective human enterovirus 71 inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2002;45(8):1644–1655. doi: 10.1021/jm010536a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lentz KN, et al. Structure of poliovirus type 2 Lansing complexed with antiviral agent SCH48973: Comparison of the structural and biological properties of three poliovirus serotypes. Structure. 1997;5(7):961–978. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00249-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arnold E, Rossmann MG. Analysis of the structure of a common cold virus, human rhinovirus 14, refined at a resolution of 3.0 Å. J Mol Biol. 1990;211(4):763–801. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90076-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kleywegt GJ, Brünger AT. Checking your imagination: Applications of the free R value. Structure. 1996;4(8):897–904. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shih SR, et al. Mutation in enterovirus 71 capsid protein VP1 confers resistance to the inhibitory effects of pyridyl imidazolidinone. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(9):3523–3529. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3523-3529.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Badger J, Minor I, Oliveira MA, Smith TJ, Rossmann MG. Structural analysis of antiviral agents that interact with the capsid of human rhinoviruses. Proteins. 1989;6(1):1–19. doi: 10.1002/prot.340060102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hadfield AT, Diana GD, Rossmann MG. Analysis of three structurally related antiviral compounds in complex with human rhinovirus 16. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(26):14730–14735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Plevka P, Perera R, Cardosa J, Kuhn RJ, Rossmann MG. Structure determination of enterovirus 71. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2012;68(Pt 9):1217–1222. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912025772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tong L, Rossmann MG. Rotation function calculations with GLRF program. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:594–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40(Pt 4):658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brünger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54(Pt 5):905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kleywegt GJ, Read RJ. Not your average density. Structure. 1997;5(12):1557–1569. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00305-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47(Pt 2):110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50(Pt 5):760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brandenburg B, et al. Imaging poliovirus entry in live cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(7):e183. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]