Abstract

Leukemia stem cells (LSCs) play important roles in leukemia initiation, progression, and relapse, and thus represent a critical target for therapeutic intervention. However, relatively few agents have been shown to target LSCs, slowing progress in the treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Based on in vitro and in vivo evidence, we report here that fenretinide, a well-tolerated vitamin A derivative, is capable of eradicating LSCs but not normal hematopoietic progenitor/stem cells at physiologically achievable concentrations. Fenretinide exerted a selective cytotoxic effect on primary AML CD34+ cells, especially the LSC-enriched CD34+CD38− subpopulation, whereas no significant effect was observed on normal counterparts. Methylcellulose colony formation assays further showed that fenretinide significantly suppressed the formation of colonies derived from AML CD34+ cells but not those from normal CD34+ cells. Moreover, fenretinide significantly reduced the in vivo engraftment of AML stem cells but not normal hematopoietic stem cells in a nonobese diabetic/SCID mouse xenotransplantation model. Mechanistic studies revealed that fenretinide-induced cell death was linked to a series of characteristic events, including the rapid generation of reactive oxygen species, induction of genes associated with stress responses and apoptosis, and repression of genes involved in NF-κB and Wnt signaling. Further bioinformatic analysis revealed that the fenretinide–down-regulated genes were significantly correlated with the existing poor-prognosis signatures in AML patients. Based on these findings, we propose that fenretinide is a potent agent that selectively targets LSCs, and may be of value in the treatment of AML.

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) represents a group of clonal hematopoietic stem cell disorders, in which a small subpopulation of leukemia stem cells (LSCs) are responsible for the accumulation of large numbers of immature myeloblasts in the bone marrow of AML patients. In addition to their crucial roles in leukemia initiation and progression, LSCs are also responsible for the high frequency of relapse that is characteristic of current AML therapies. Of patients receiving treatment with curative intent, less than one-half will achieve long-term survival (1). Similar to normal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), LSCs exhibit stem cell-like characteristics such as the capacity for self-renewal, differentiation potential, and relative quiescence (2, 3). The quiescent feature renders LSCs resistant to conventional chemotherapeutic agents that predominantly target proliferating rather than quiescent cells (1). For this reason, it is not surprising that relapse occurs in the majority of cases; this is further supported by recent studies showing that AML patients with LSCs enrichment have worse clinical outcomes (4–7). It is therefore crucial that therapies be developed targeting the quiescent and drug-resistant LSCs.

Despite the similarities shared by LSCs and HSCs, LSCs often possess several unique features as well, which may provide important hints for designing LSC-targeted therapy. For instance, LSCs are usually associated with the abnormal expression of CD markers (e.g., CD44, CD47, CD96, and CD123), constitutive activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB), active Wnt/β-catenin signaling, and elevated levels of interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) and death-associated protein kinase (DAPK) (8–12). Most recently, emerging evidence points to oxidative signaling as being a two-edged sword in AML: moderate levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are important for driving disease, whereas higher levels result in cell death (13–15). The dual roles of oxidative signaling suggest that LSCs, in comparison with normal HSCs, are more vulnerable to ROS-generating agents. Accordingly, pharmacological agents favoring the generation of ROS are worth exploring in LSC-targeted therapy. Indeed, ROS induction has been shown as a critical mechanism for the selective eradication of LSCs by several compounds, such as parthenolide (PTL), dimethyl-aminoparthenolide (DMAPT), 4-benzyl-2-methyl-1,2,4-thiadiazolidine-3,5-dione (TDZD-8), and 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) (16–19).

Another promising agent that could be used in this regard is fenretinide, a synthetic retinoid that lacks a carboxyl functional group likely necessary for retinoid receptor activity (20). We and others have previously demonstrated that fenretinide, unlike classical retinoids that often induce differentiation, triggers apoptotic effects; it is largely achieved through the generation of ROS (21–24), enhanced cellular ceramide, and/or ganglioside D3 (25). Moreover, several key stem cell survival-associated signaling pathways, such as NF-κB, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), have been reported to be inactivated in the fenretinide-induced apoptosis in different cancer cell types (25, 26); this further suggests the therapeutic value of fenretinide in targeting cancer stem cells.

Fenretinide has been used clinically for some time as an effective chemopreventive agent for various cancers (27). It can significantly reduce the risk of breast cancer and small cell lung cancer (28, 29), suggesting an ability to prevent the development of cancer and/or eliminate early-stage malignant cells (likely cancer-initiating cells). Furthermore, long-term clinical trials have demonstrated only minimal side effects in patients receiving fenretinide (28, 30–32). In particular, no significant hematopoietic toxicity has been observed in patients treated with fenretinide (28). To illustrate the potential value of fenretinide in AML therapies, in this study, we defined the fenretinide effects on primary AML CD34+ cells and LSC-enriched AML CD34+CD38− cells.

Results

Fenretinide Preferentially Induces Death of Primary AML CD34+ Cells but Not Normal CD34+ Hematopoietic Cells.

Our initial study was performed to compare fenretinide effects on AML CD34+ and normal CD34+ cells using 32 primary AML and 6 normal samples. The AML specimens were classified into different French–American–British (FAB) subtypes (including M0, M1, M2, M4, M5, and M6), thus representing the spectrum of AML subtypes. The clinical characteristics of these patients are described in Table S1. In the clinic, it is possible to achieve plasma concentrations of 10 μM while maintaining minimal side effects in patients receiving standard doses of fenretinide (28, 32). We therefore treated CD34+ cells with concentrations of fenretinide ranging from 2.5 to 7.5 μM to evaluate its effect. We determined cell viability and apoptosis by Annexin V and 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) staining after 18 h of treatment. As shown in Table 1, fenretinide exerted a dose-dependent cytotoxic effect on AML CD34+ cells (75.3%, 49.0%, and 26.5% viable cells for 2.5, 5, and 7.5 μM, respectively). Moreover, we found that fenretinide killed AML CD34+ cells mainly through apoptosis, as indicated by a significant increase in the number of Annexin V-positive apoptotic cells (Table S2 and Fig. S1). In contrast, no significant effect on the viability and apoptosis was observed in normal CD34+ cells at the concentrations of 2.5 and 5 μM (92.4% and 95.4% viable cells, and 4.9% and 3.0% apoptotic cells, respectively) (Table 1 and Table S2), and only a moderate toxicity (61.5% viable and 23.1% apoptotic cells) was observed in normal specimens after treatment with 7.5 μM fenretinide.

Table 1.

Fenretinide on AML and normal CD34+ cell viability

| Viable cells, % |

||||

| Specimens | Untreated | 2.5 μM | 5 μM | 7.5 μM |

| AML specimens | ||||

| AML1 | 87.3 | 48.9 | 14.3 | 0.3 |

| AML2 | 67.1 | 55.9 | 19.0 | 3.8 |

| AML3 | 83.9 | 68.7 | 58.3 | 29.0 |

| AML4 | 90.1 | 77.5 | 24.2 | 1.1 |

| AML5 | 86.8 | 61.2 | 19.5 | 8.9 |

| AML6 | 97.3 | 66.2 | 12.0 | 0.4 |

| AML7 | 86.9 | 80.3 | 77.2 | 60.2 |

| AML8 | 92.8 | 73.3 | 58.9 | 7.6 |

| AML9 | 90.2 | 81.5 | 54.3 | 7.2 |

| AML10 | 93.1 | 75.2 | 19.5 | 0.8 |

| AML11 | 91.7 | 97.2 | 63.9 | 13.6 |

| AML12 | 91.3 | 81.5 | 46.1 | ND |

| AML13 | 80.3 | 98.3 | 69.3 | 1.8 |

| AML14 | 92.9 | 93.4 | 72.3 | 5.5 |

| AML15 | 73.6 | 69.7 | 47.2 | 17.8 |

| AML16 | 67.6 | 44.1 | 36.2 | 24.2 |

| AML17 | 88.2 | 89.4 | 65.3 | 42.5 |

| AML18 | 90.8 | 87.3 | 85.1 | 86.1 |

| AML19 | 96.7 | 90.3 | 89.4 | 87.8 |

| AML20 | 80.1 | 78.4 | 70.2 | 56.4 |

| AML21 | 61.4 | 30.5 | 15.3 | 7.1 |

| AML22 | 98.7 | 72.7 | 21.5 | ND |

| AML23 | 91.2 | 98.3 | 88.1 | ND |

| AML24 | 95.9 | 94.1 | 89.9 | 78.1 |

| AML25 | 79.1 | 70.4 | 35.6 | 18.2 |

| AML26 | 88.7 | 58.3 | 33.2 | 16.2 |

| AML27 | 98.7 | 95.7 | 94.7 | 93.2 |

| AML28 | 65.7 | 61.3 | 36.2 | 19.1 |

| AML29 | 82.3 | 78.2 | 40.7 | 9.2 |

| AML30 | 93.9 | 89.2 | 33.2 | 11.1 |

| AML31 | 87.1 | 69.7 | 37.8 | 23.1 |

| AML32 | 78.9 | 71.9 | 41.3 | 37.3 |

| Mean | 86.0 ± 1.8 | 75.3 ± 2.9* | 49.0 ± 4.5† | 26.5 ± 5.4‡ |

| Normal specimens | ||||

| N1 | 93.3 | 93.5 | 98.6 | 95.5 |

| N2 | 92.1 | 90.2 | 85.5 | 23.2 |

| N3 | 93.8 | 92.2 | 97.9 | 28.0 |

| N4 | 95.4 | 93.2 | 99.1 | 82.8 |

| N5 | 92.7 | 93.0 | 99.3 | 68.3 |

| N6 | 95.1 | 92.2 | 91.7 | 71.2 |

| Mean | 93.7 ± 0.5 | 92.4 ± 0.5 | 95.4 ± 2.3 | 61.5 ± 12.1 |

ND, not determined.

Lower viability (P < 0.05) than normal subjects.

1.9-fold lower viability (P < 0.0005) than normal subjects.

2.3-fold lower viability (P < 0.0005) than normal subjects.

Fenretinide Selectively Targets More Primitive AML CD34+CD38− Cells.

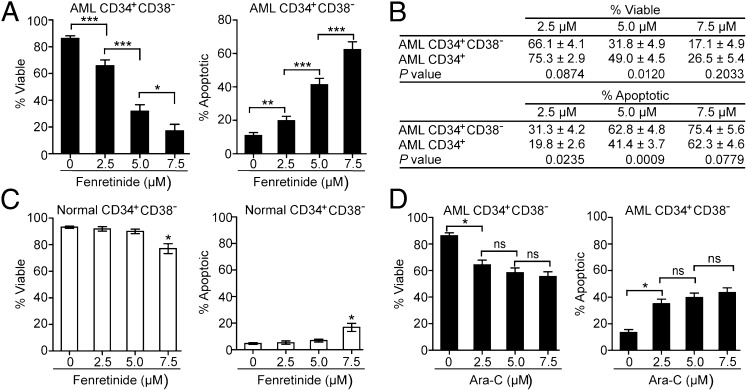

Because LSCs and HSCs are mostly enriched in the CD34+CD38− subpopulation (3), we further assessed the fenretinide effect on this subpopulation. As shown in Fig. 1A, fenretinide demonstrated a significant dose-dependent cytotoxic effect on AML CD34+CD38− cells. It was noteworthy that the fenretinide effect on AML CD34+CD38− cells was made even more apparent compared with that on AML CD34+ cells (Fig. 1B). In addition, the effect on normal hematopoietic cells bearing a CD34+CD38− immunophenotype was still not significant, except at the highest dose of treatment (Fig. 1C). Together, the data indicate that fenretinide preferentially eradicates LSCs but not normal HSCs.

Fig. 1.

Fenretinide selectively targets AML CD34+CD38− cells but not normal CD34+CD38− hematopoietic cells. (A) Effect of fenretinide treatment on primary AML CD34+CD38− cells (n = 32). (B) Comparison of the fenretinide effect on AML CD34+ and AML CD34+CD38− cells. (C) Effect of fenretinide treatment on normal CD34+CD38− hematopoietic cells (n = 6). (D) Effect of Ara-C treatment on AML CD34+CD38− cells (n = 32). Each error bar represents the SEM. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, no significance.

To compare the effectiveness of fenretinide to conventional chemotherapeutic agents in targeting LSCs, we performed side-by-side studies with cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C), one of the staples in the first-line treatment for AML. As illustrated in Fig. 1D, Ara-C had only a minor/moderate effect on both cell viability and apoptosis in AML CD34+CD38− cells. In keeping with previous studies (17), Ara-C–induced cell killing reached a plateau at concentrations between 5 and 7.5 μM. Such plateau was not observed for fenretinide (Fig. 1A).

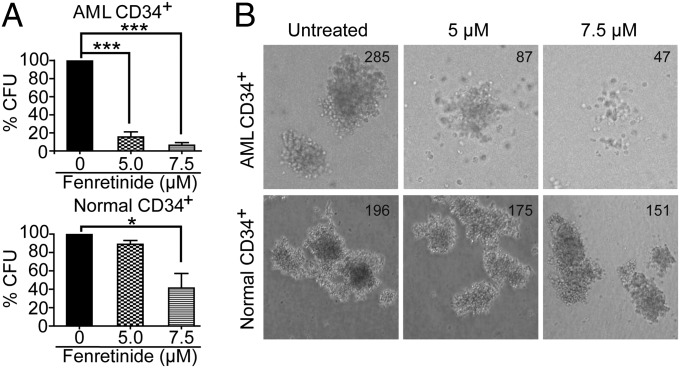

Fenretinide Suppresses Colony Formation at the Progenitor and Stem Cell Levels.

The above data indicate that fenretinide is cytotoxic to AML CD34+ cells, and even more so with regard to the AML CD34+CD38− subpopulation. To further characterize the fenretinide effect on the functional subsets of AML cells, we performed methylcellulose colony-forming unit (CFU) assays to determine whether fenretinide would functionally affect cells capable of forming leukemic cell colonies. As illustrated in Fig. 2 and Table S3, fenretinide treatment strongly reduced the ability of primary AML CD34+ cells to form colonies (mean CFU inhibition, 84.50% for 5 μM and 93.59% for 7.5 μM; n = 14). The data indicate that fenretinide inhibits the proliferative potential of AML colony-forming cells. In contrast, the colony-forming ability of normal hematopoietic progenitor cells was not substantially affected by 5 μM fenretinide. When the concentration of fenretinide was increased to 7.5 μM, there was moderate impairment, consistent with the above observation of the fenretinide effect on cell viability and apoptosis. Therefore, the concentration of 5 μM was used in the subsequent experiments.

Fig. 2.

Fenretinide ablates the colony-forming ability of primary AML stem/progenitor cells but not normal counterparts. (A) The in vitro colony-forming ability of AML CD34+ cells (n = 14) and normal CD34+ cells (n = 4) was examined in the absence or presence of fenretinide. All assays were performed in triplicate. Each error bar represents the SEM. ***P < 0.001; *P < 0.05. (B) The representative CFU microscopy images are shown as indicated.

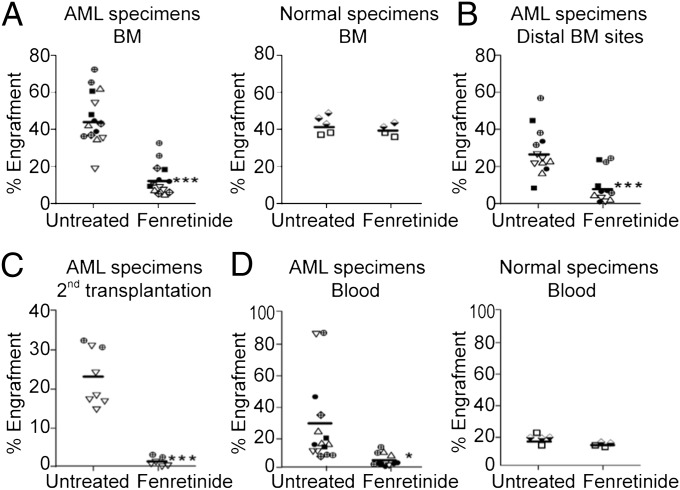

Fenretinide Preferentially Suppresses Engraftment of AML LSCs Rather than Normal HSCs.

To further analyze whether fenretinide can selectively eliminate LSCs capable of developing leukemia in vivo, we used the nonobese diabetic (NOD)/SCID xenotransplantation model to assess the in vivo long-term engraftment potential of LSCs and HSCs after fenretinide treatment. We conducted the in vivo engraftment studies using six primary AML and two normal hematopoietic samples. We treated samples with 5 μM fenretinide for 18 h and transplanted them into sublethally irradiated NOD/SCID mice using intrabone marrow injection. At 5–12 wk after transplantation, the mice were killed and the percentage of engrafted human cells in each mouse was determined using anti-human CD45 antibody. As shown in Fig. 3A, fenretinide significantly reduced the in vivo engraftment of AML leukemic cells (from 42.73 ± 13.35% to 13.34 ± 8.41%, P < 0.001) in the NOD/SCID mice. In contrast, there was no decrease in the engraftment in mice receiving fenretinide-treated normal hematopoietic cells (Fig. 3A, Right). Furthermore, we found that fenretinide treatment also reduced engraftment in the noninjected bone marrow sites of the mice (Fig. 3B), indicating that fenretinide impaired the migration of LSCs. To determine conclusively whether LSCs remained in mice transplanted with fenretinide-treated cells, we performed secondary transplantation. As illustrated in Fig. 3C, bone marrow cells harvested from recipients that had received fenretinide-treated AML cells were unable to repopulate secondary recipients, whereas bone marrow cells taken from mice that had received untreated cells did engraft in secondary mice. The data suggest that LSCs treated with fenretinide have lost the ability to self-renew. Consistent with the reduction of bone marrow engraftment, we also observed a marked decrease in the number of leukemia cells in the peripheral blood after fenretinide treatment (Fig. 3D). In summary, the xenotransplantation experiments indicate that fenretinide reduces the ability of LSCs to initiate AML and attenuates leukemic cell growth, but without affecting the engraftment of normal HSCs.

Fig. 3.

Fenretinide impairs the in vivo initiating ability for AML. (A) Effect of fenretinide treatment on the engraftment of AML or normal cells. (B) Percentage of engraftment in the noninjected distal bone marrow sites. (C) Percentage of engraftment in the secondary recipients that had received untreated or fenretinide-treated AML cells. (D) Percentage of engraftment of AML or normal cells in the peripheral blood. In each plot, the horizontal bar indicates the median engraftment and each symbol represents an individual mouse. ***P < 0.001; *P < 0.05. ▵, AML13; ▿, AML17;  , AML22; ▪, AML31;

, AML22; ▪, AML31;  , AML32; ●, AML37.

, AML32; ●, AML37.

Transcriptome Analysis Reveals Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Fenretinide-Induced Apoptosis.

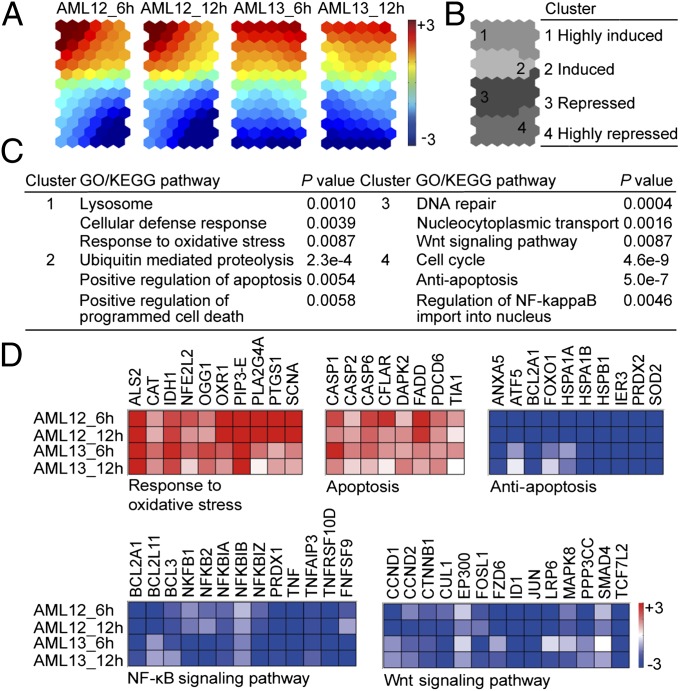

To identify molecular mechanisms underlying fenretinide-induced apoptosis, we then performed microarray gene expression profiling of AML CD34+ cells isolated from two independent AML specimens. Each sample was treated with 5 μM fenretinide for 6 and 12 h. In comparison with the untreated control, we selected genes with consistent expression changes across the two AML specimens: this resulted in the identification of 2,674 commonly regulated transcripts (Dataset S1). We carried out a self-organizing map (SOM)-based gene clustering analysis (33, 34). As shown in Fig. 4, similar expression changes were revealed at each of two time points (Fig. 4A), and genes were grouped into four distinct clusters: highly induced (cluster 1), induced (cluster 2), repressed (cluster 3), and highly repressed (cluster 4) (Fig. 4B). To reveal the functional relevance of fenretinide-regulated genes, we next performed functional enrichment analysis using DAVID (35), and the mechanisms revealed were summarized below.

Fig. 4.

Transcriptome analysis of fenretinide-induced apoptosis of AML CD34+ cells suggests the induction of stress response events and the repression of NF-κB and Wnt signaling. (A) Illustration of transcriptome changes of fenretinide-treated primary AML CD34+ cells by component plane presentation integrated self-organizing map (CPP-SOM). Each presentation illustrates sample-specific changes, in which the up-regulated (red), down-regulated (blue), and moderately regulated (yellow or green) genes are well delineated. (B) Illustration of four gene clusters on a SOM map. (C) Functional enrichment analysis of fenretinide-regulated genes using DAVID. (D) Major functional features associated with fenretinide-treated AML CD34+ cells. The color bar stands for expression values (log ratio with base 2). Detailed gene descriptions are available in Dataset S1.

Fenretinide-induced genes are linked to stress-responsive events and apoptosis induction.

One pathway of particular interest is the response to oxidative stress; genes in this pathway were significantly enriched in cluster 1 (highly induced) (Fig. 4C). These included the up-regulation of NRF2, CAT, OGG1, IDH1, and ALS2 (Fig. 4D). In addition, there was evidence for activation of pathways involved in the cellular defense response and apoptosis induction in clusters 1 (highly induced) and 2 (induced) (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that the activation of stress-mediated responses is an important feature of fenretinide-induced killing of AML CD34+ cells.

Fenretinide-repressed genes are associated with cell survival, NF-κB and Wnt signaling.

Through identifying functional groups or signaling pathways enriched in down-regulated clusters (clusters 3 and 4), we found that the genes in these clusters were more diverse, spanning a wide spectrum of functions (Fig. 4 C and D). Among them, the most significant gene ontology (GO) terms and pathways were those associated with cell survival. For instance, antiapoptosis genes (BCL2L11, BCL2A1, and ATF5) were down-regulated by fenretinide treatment. We also found that genes associated with unique properties of LSCs were significantly enriched in the down-regulated clusters. For example, the constitutive activation of NF-κB is a major distinguishing characteristic between HSCs and LSCs (8); we found that fenretinide significantly suppressed this signaling pathway. As shown in Fig. 4D, genes repressed in the NF-κB pathway included the regulatory subunits of the NF-κB complexes (NFKB1, NFKB2, NFKBIA, and NFKBIB), NF-κB upstream members (TNF and TNFAIP3), and NF-κB target genes (BCL2 and BCL3). Moreover, we found that the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which is required for self-renewal of LSCs (12), was also enriched in fenretinide-repressed genes, as highlighted by CTNNB1 and its target genes FOS, ID1, JUN, EP300, and SMAD4.

Molecular Mechanisms Revealed from Transcriptome Analysis Were Validated by Independent Approaches.

Fenretinide effects involve induction of oxidative stress.

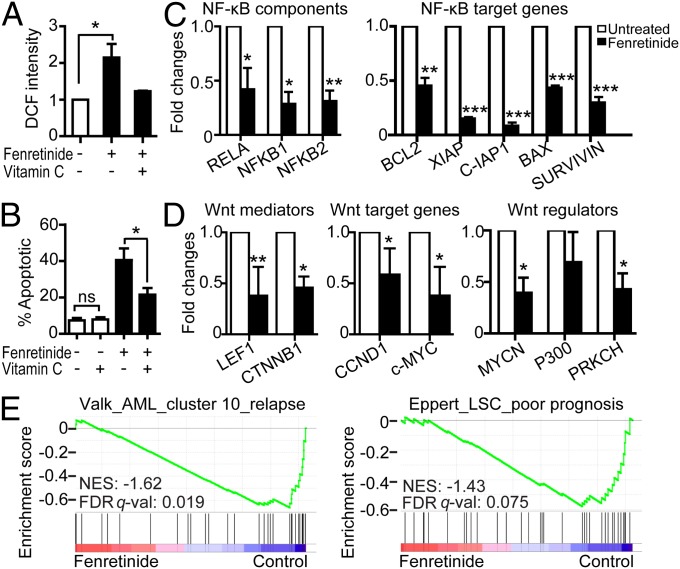

Because fenretinide is known as a ROS-inducing agent (21–24), up-regulation of oxidative stress-responsive genes during fenretinide-induced apoptosis is most likely triggered by fenretinide-induced ROS production. We therefore stained primary AML CD34+ cells with 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), a widely used redox-sensitive dye, to measure intracellular ROS production upon fenretinide treatment. As shown in Fig. 5A, an approximately twofold increase in 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) fluorescence was observed in fenretinide-treated AML CD34+ cells; this increase occurred as early as 30 min after fenretinide exposure. This confirms the previous reports that fenretinide stimulation causes a rapid increase of intracellular ROS (25, 36). To further determine the role of ROS in fenretinide-induced apoptosis, we treated AML CD34+ cells with an antioxidant (100 μM vitamin C) for 3 h before fenretinide treatment. The pretreatment not only blocked the fenretinide-induced ROS generation (Fig. 5A) but also prominently reduced fenretinide-induced apoptosis (Fig. 5B), indicating that fenretinide-induced oxidative stress was mediated by the elevated ROS levels.

Fig. 5.

Validation of molecular features revealed from transcriptome analysis. (A) ROS production of AML CD34+ cells (n = 6) exposed to 5 μM fenretinide for 30 min with/without 3-h pretreatment of vitamin C. (B) Effect of fenretinide treatment on apoptosis of AML CD34+ cells after vitamin C pretreatment. (C and D) The expression changes of genes involved in NF-κB (C) and Wnt (D) signaling upon fenretinide treatment. The relative expression levels were normalized to GAPDH expression. Error bars in A–D represent the SEM. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, no significance. (E) Correlation between fenretinide–down-regulated genes and gene sets indicating poor prognosis in AML. (Right) The poor-prognosis–associated gene set in AML patients (39). (Left) The LSC-specific gene set associated with poor prognosis of AML (4). FDR q-val, false discovery rate q value; NES, normalized enrichment score. Detailed gene descriptions are available in Dataset S1.

Fenretinide inhibits expression of genes critical for NF-κB and Wnt signaling.

The NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways have been shown to play important roles in cell proliferation and survival of AML cells, particularly LSCs (8, 12, 37). To verify the global gene expression findings, we treated three further AML samples with fenretinide and examined changes in the expression of genes involved in NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin signaling by real-time RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 5C, both the components of the NF-κB complex (RELA, NFKB1, and NFKB2) and the target genes of NF-κB (BCL2, XIAP, c-IAP1, BAK, and Survivin) were markedly reduced in fenretinide-treated samples. Also, the key mediator of Wnt signaling β-catenin (CTNNB1) and its directly interacted transcription factor LEF1, the Wnt pathway activators (MYCN and PRKCH), and the Wnt target genes (CCND1 and c-MYC) were remarkably suppressed after fenretinide treatment (Fig. 5D).

Fenretinide–down-regulated genes are correlated with the poor outcome of AML.

Still, an important question that remains to be addressed is the clinical relevance of fenretinide-regulated genes. To address this question, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (38) of our expression data with several AML outcome-related gene sets/signatures (Dataset S2). First, we examined the relationship between fenretinide-regulated genes and the existing AML prognostic signatures (39). GSEA revealed that fenretinide–down-regulated genes were significantly correlated with the worst prognosis signatures (Fig. 5E, Left), whereas signatures associated with good or intermediate prognosis were minimally influenced by fenretinide (Fig. S2). A recent study has demonstrated that AML samples with worse prognosis tend to express stem cell-related genes more prominently than less aggressive AML samples (4). We thus retrieved a LSC-specific and poor-prognosis–associated gene set (4) and found a marked down-regulation of genes in this gene set after fenretinide treatment (Fig. 5E, Right). Overall, the results suggest that fenretinide treatment might repress the expression of LSC-specific genes associated with the worse outcome of AML.

Discussion

LSCs are crucial in leukemia initiation, progression, metastasis, and relapse. Their residual levels are strongly correlated with the prognosis of individual AML patients. Recently, much attention has been paid to the development of strategies that selectively eliminate LSCs, which may prevent the recurrence of leukemia and eventually cure the disease. The significance of this study is to stratify the unique anti-LSC effects of fenretinide through a series of in vitro and in vivo experiments. We found fenretinide exerted a selective cytotoxic effect on primary AML CD34+ cells, especially the LSC-enriched CD34+CD38− subpopulation, whereas no significant effect was observed on normal counterparts, suggesting the capacity of fenretinide to kill AML stem/progenitor cells. Based on this finding, we continued our study using methylcellulose CFU assays and showed that fenretinide was able to reduce the ability of primary AML CD34+ cells to form colonies in semisolid medium, which provides evidence that fenretinide inhibited the growth of AML progenitor cells. Finally, using the NOD/SCID mouse model, we found that fenretinide reduced the degree of engraftment of primary AML cells, and inhibited the ability of treated cells that were recovered from mice to engraft secondary recipients. This indicates that the fenretinide treatment inhibited the disease-perpetuating feature of self-renewal. Importantly, there was minimal effect of fenretinide on normal blood forming cells at a dose that affected AML cells.

Mechanistic studies allowed us to gain some important insights into the effects of fenretinide in eradicating LSCs. Transcriptome analysis of fenretinide-treated AML CD34+ cells identified a number of features, typifying activation of ROS-induced stress responses. The role of ROS was confirmed by the cellular experiments demonstrating that primary AML CD34+ cells exposed to fenretinide for only 30 min showed an increase of intracellular ROS. Further observations that the antioxidant agent vitamin C could protect primary AML CD34+ cells from fenretinide-induced cell death provided confirmation for a role of ROS in fenretinide-induced apoptosis. Moreover, we observed an increased level of NRF2, consistent with the previous finding that NRF2 is involved in LSC-specific apoptosis induced by DMAPT, another newly identified compound that can specifically target LSCs (18). In addition, we also found that FoxO1, the key transcription factor involved in the anti-ROS program (14), was down-regulated by fenretinide, providing an extra support for the fenretinide-disturbed ROS-scavenging system in LSCs.

Aside from being a ROS inducer, we found that fenretinide inhibited the NF-κB signaling, an important pathway linked to LSCs. The inhibition of NF-κB signaling has been reported in the apoptosis of LSCs induced by other compounds, such as PTL (17). However, studies on primary AML cells have demonstrated that NF-κB inhibition alone does not effectively impair their engraftment potential in vivo. Most likely, NF-κB inhibition helps to increase cell sensitivity to anticancer chemotherapeutic agents (40). NF-κB, known as a redox-sensitive transcription factor, can also protect AML cells from death through limiting ROS levels. The inactivation of NF-κB can further increase intracellular ROS levels (41), and thus enhance cell death. This is a potential advantage of combining fenretinide with chemotherapeutics, such as daunorubicin, which also kills cells through increasing the ROS levels. Within this context, cell-killing activity of fenretinide may be enhanced when the NF-κB adaptive response is limited. Therefore, we hypothesize that the cytotoxic effects and overall efficacy of fenretinide may be accomplished by the ROS induction together with the inhibition of NF-κB.

Intriguingly, the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, required for the development of LSCs (12), was also inhibited after exposure to fenretinide. The importance of this pathway is highlighted by its role in maintaining the survival of LSCs (12) and other stem-like cancer cells found in breast cancer, colon cancer, and multiple myeloma (42). Given the importance of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, it is actively targeted as a cancer treatment (43). For example, inactivating Wnt/β-catenin is suggested for treating chemoresistant cancers and also for sensitizing cancer cells to chemotherapeutic agents. Although the exact involvement of Wnt/β-catenin signaling remains to elucidate, the repression of this pathway not only provides a promising explanation for fenretinide targeting LSCs but also suggests the possibility of synergizing the effect of fenretinide on LSCs through inhibition of the Wnt signaling.

Fenretinide has been studied extensively in animals and humans as an anticancer agent and used to protect against the development of cancer. Clinical trials have demonstrated that the mean plasma fenretinide level is 7.40 ± 4.25 μM in patients receiving fenretinide 1,800 mg/m2 per day (28). In keeping with the minimal toxicity, fenretinide had no effects on normal hematopoiesis in patients taking the drug (28, 30–32). The repeated administrations of the highest dose (4,000 mg/m2) produced side effects (such as nausea, hot flashes, constipation, and nyctalopia) in only one-third of the evaluable cases, and these side effects were recovered spontaneously after discontinuation (30, 31). Thus, it is possible to achieve the level of 5 µM in human, the effective dose used in this study. Based on our results presented here, clinical trials of fenretinide in humans either alone or in combination are warranted. The inhibitory effects on NF-κB and Wnt/β-catenin signaling may add benefits in reducing the toxicity of standard chemotherapeutics and sensitizing cancer cells to these agents.

Materials and Methods

Specimens and Reagents.

This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from patients or their guardians. Thirty-seven newly diagnosed AML bone marrow samples (Table S1) and six umbilical cord blood (UCB) specimens were involved in this study. Details regarding sample preparation and reagents used are available in SI Materials and Methods.

Flow Cytometry and ROS Measurement.

Apoptosis was analyzed by a FACStar Plus flow cytometer (Becton-Dickinson). Intracellular level of ROS was measured using the oxidation-sensitive fluorescent dye DCFH-DA. Details are available in SI Materials and Methods.

Methylcellulose CFU Assays.

Human AML-CFUs and UCB-CFUs were assayed in culture conditions as previously described with some minor modifications (17). Details are available in SI Materials and Methods.

Mouse Xenotransplantation.

NOD/SCID mice (Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Company) were sublethally irradiated with 11 rad/g by a 137Cs irradiator (Gammacell 3000 Elan; MDS Nordin). The same amounts of fenretinide-treated or untreated AML cells and UCB mononuclear cells were injected into the left femur marrow cavity. After 5–12 wk, mice were killed and bone marrow was analyzed for the presence of human cells using flow cytometry. AML engraftment was defined by two features: (i) the presence of a large proportion of CD45+CD33+CD19− cells and a hardly detectable fraction of CD45+CD33−CD19+ cells by flow cytometry (Fig. S3A); (ii) an immature blast-like morphology similar to the leukemic blasts by Wright–Giemsa staining (Fig. S3B). All experimental procedures were performed in compliance with the regulations of the Animal Care Committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. Details are available in SI Materials and Methods.

Gene Expression Analyses.

Two AML CD34+ samples were collected for microarray analysis using Human Genome-U133 plus 2.0 array (Affymetrix). Detailed bioinformatics analyses are available in SI Materials and Methods.

Real-Time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from untreated and fenretinide-treated AML CD34+ cells using the RNeasy Kit from Qiagen. Real-time RT-PCR was performed as previously described (44). Primers used in this assay were listed in Table S4. Each assay was performed in triplicate.

GSEA.

GSEA was performed using GSEA, version 2.0 (38), with genes ranked by signal-to-noise ratio, and statistical significance was determined by 1,000 gene set permutations. AML outcome-related gene sets (39) and LSC-specific gene sets (4) (Dataset S2) were obtained from the indicated publications.

Statistical Analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad). For two-group comparisons, significance was determined by two-tailed t tests.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shumin Xiong, Bin Chen, and Xiangqin Weng for expert advice regarding morphology examination, cytogenetic analysis, and flow cytometry analysis, and Yanzhi Du, Wen Jin, and Jianfei Fan for assistance with experiments. This work was supported in part by Ministry of Science and Technology Grants of China 2009CB825607, 2012AA02A211, and 2011CB910202, and National Natural Science Foundation Grants of China 81270625, 31171257, and 90919059.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The microarray expression data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE33243).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1302352110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Tallman MS, Gilliland DG, Rowe JM. Drug therapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2005;106(4):1154–1163. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjerkvig R, Tysnes BB, Aboody KS, Najbauer J, Terzis AJ. Opinion: The origin of the cancer stem cell: Current controversies and new insights. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(11):899–904. doi: 10.1038/nrc1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414(6859):105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eppert K, et al. Stem cell gene expression programs influence clinical outcome in human leukemia. Nat Med. 2011;17(9):1086–1093. doi: 10.1038/nm.2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gentles AJ, Plevritis SK, Majeti R, Alizadeh AA. Association of a leukemic stem cell gene expression signature with clinical outcomes in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA. 2010;304(24):2706–2715. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearce DJ, et al. AML engraftment in the NOD/SCID assay reflects the outcome of AML: Implications for our understanding of the heterogeneity of AML. Blood. 2006;107(3):1166–1173. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Rhenen A, et al. High stem cell frequency in acute myeloid leukemia at diagnosis predicts high minimal residual disease and poor survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(18):6520–6527. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guzman ML, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB is constitutively activated in primitive human acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Blood. 2001;98(8):2301–2307. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.8.2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzman ML, et al. Expression of tumor-suppressor genes interferon regulatory factor 1 and death-associated protein kinase in primitive acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Blood. 2001;97(7):2177–2179. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.7.2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jordan CT. Targeting myeloid leukemia stem cells. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(31):31ps21. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan CT, Guzman ML, Noble M. Cancer stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(12):1253–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, et al. The Wnt/beta-catenin pathway is required for the development of leukemia stem cells in AML. Science. 2010;327(5973):1650–1653. doi: 10.1126/science.1186624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdel-Wahab O, Levine RL. Metabolism and the leukemic stem cell. J Exp Med. 2010;207(4):677–680. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tothova Z, Gilliland DG. FoxO transcription factors and stem cell homeostasis: Insights from the hematopoietic system. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(2):140–152. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trachootham D, Alexandre J, Huang P. Targeting cancer cells by ROS-mediated mechanisms: A radical therapeutic approach? Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(7):579–591. doi: 10.1038/nrd2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guzman ML, et al. Rapid and selective death of leukemia stem and progenitor cells induced by the compound 4-benzyl, 2-methyl, 1,2,4-thiadiazolidine, 3,5 dione (TDZD-8) Blood. 2007;110(13):4436–4444. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-088815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guzman ML, et al. The sesquiterpene lactone parthenolide induces apoptosis of human acute myelogenous leukemia stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 2005;105(11):4163–4169. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-4135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guzman ML, et al. An orally bioavailable parthenolide analog selectively eradicates acute myelogenous leukemia stem and progenitor cells. Blood. 2007;110(13):4427–4435. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-090621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hassane DC, et al. Discovery of agents that eradicate leukemia stem cells using an in silico screen of public gene expression data. Blood. 2008;111(12):5654–5662. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-126003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Formelli F, Barua AB, Olson JA. Bioactivities of N-(4-hydroxyphenyl) retinamide and retinoyl beta-glucuronide. FASEB J. 1996;10(9):1014–1024. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.9.8801162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiPietrantonio AM, et al. Fenretinide-induced caspase 3 activity involves increased protein stability in a mechanism distinct from reactive oxygen species elevation. Cancer Res. 2000;60(16):4331–4335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goto H, Takahashi H, Fujii H, Ikuta K, Yokota S. N-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)retinamide (4-HPR) induces leukemia cell death via generation of reactive oxygen species. Int J Hematol. 2003;78(3):219–225. doi: 10.1007/BF02983798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang L, et al. Preferential involvement of both ROS and ceramide in fenretinide-induced apoptosis of HL60 rather than NB4 and U937 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;405(2):314–318. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oridate N, et al. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide-induced apoptosis in cervical carcinoma cells. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89(16):1191–1198. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.16.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu JM, DiPietrantonio AM, Hsieh TC. Mechanism of fenretinide (4-HPR)-induced cell death. Apoptosis. 2001;6(5):377–388. doi: 10.1023/a:1011342220621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimada K, et al. Contributions of mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor kappa B to N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)retinamide-induced apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2002;35(3):127–137. doi: 10.1002/mc.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malone W, Perloff M, Crowell J, Sigman C, Higley H. Fenretinide: A prototype cancer prevention drug. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2003;12(11):1829–1842. doi: 10.1517/13543784.12.11.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider BJ, et al. Phase II trial of fenretinide (NSC 374551) in patients with recurrent small cell lung cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2009;27(6):571–578. doi: 10.1007/s10637-009-9228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veronesi U, et al. Fifteen-year results of a randomized phase III trial of fenretinide to prevent second breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(7):1065–1071. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garaventa A, et al. Phase I trial and pharmacokinetics of fenretinide in children with neuroblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(6):2032–2039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villablanca JG, et al. Phase I trial of oral fenretinide in children with high-risk solid tumors: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group (CCG 09709) J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(21):3423–3430. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Puduvalli VK, et al. Phase II study of fenretinide (NSC 374551) in adults with recurrent malignant gliomas: A North American Brain Tumor Consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(21):4282–4289. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Du Y, et al. Coordination of intrinsic, extrinsic, and endoplasmic reticulum-mediated apoptosis by imatinib mesylate combined with arsenic trioxide in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2006;107(4):1582–1590. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang H, et al. A topology-preserving selection and clustering approach to multidimensional biological data. OMICS. 2011;15(7–8):483–494. doi: 10.1089/omi.2010.0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang K, et al. Converting redox signaling to apoptotic activities by stress-responsive regulators HSF1 and NRF2 in fenretinide treated cancer cells. PLoS One. 2009;4(10):e7538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reya T, et al. A role for Wnt signalling in self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423(6938):409–414. doi: 10.1038/nature01593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(43):15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valk PJ, et al. Prognostically useful gene-expression profiles in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(16):1617–1628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakanishi C, Toi M. Nuclear factor-kappaB inhibitors as sensitizers to anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(4):297–309. doi: 10.1038/nrc1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Anderson MT, Staal FJ, Gitler C, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA. Separation of oxidant-initiated and redox-regulated steps in the NF-kappa B signal transduction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91(24):11527–11531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takahashi-Yanaga F, Kahn M. Targeting Wnt signaling: Can we safely eradicate cancer stem cells? Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(12):3153–3162. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takebe N, Harris PJ, Warren RQ, Ivy SP. Targeting cancer stem cells by inhibiting Wnt, Notch, and Hedgehog pathways. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(2):97–106. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu X, et al. The significance of low PU.1 expression in patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Hematol Oncol. 2012;5:22. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.