Abstract

The venom of cone snails has been the subject of intense studies because it contains small neuroactive peptides of therapeutic value. However, much less is known about their larger proteins counterparts and their role in prey envenomation. Here, we analyzed the proteolytic enzymes in the injected venom of Conus purpurascens and Conus ermineus (piscivorous), and the dissected venom of Conus purpurascens, Conus marmoreus (molluscivorous) and Conus virgo (vermivorous). Zymograms show that all venom samples displayed proteolytic activity on gelatin. However, the electrophoresis patterns and sizes of the proteases varied considerably among these four species. The protease distribution also varied dramatically between the injected and dissected venom of C. purpurascens. Protease inhibitors demonstrated that serine and metalloproteases are responsible for the gelatinolytic activity. We found fibrinogenolytic activity in the injected venom of C. ermineus suggesting that this venom might have effects on the hemostatic system of the prey. Remarkable differences in protein and protease expression were found in different sections of the venom duct, indicating that these components are related to the storage granules and that they participate in venom biosynthesis. Consequently, different conoproteases play major roles in venom processing and prey envenomation.

Keywords: Conus, venom, conoproteins, conoproteases, fibrinogenolytic, gelatinolytic

1. Introduction

The venom of predatory animals, such as snakes, spiders, scorpions, sea anemones and cone snails, contain an extraordinary array of peptides and proteins that target specific ion channels, neuronal receptors, and disrupt membranes and tissues as part of their envenomation strategy for predation. The venom of cone snails, a genus (Conus ssp.) of marine gastropods that includes more than 700 extant species, varies dramatically from species to species. Conus species show prey preferences, as some prey upon fish (piscivorous), others on mollusks (molluscivorous) and the vast majority of cone snails feed on worms (vermivorous). There are enormous differences in the physiology, behavior and venom composition among cone snails depending on their prey preferences.

The venom apparatus comprises a venom duct, where the venom is synthesized and stored; a venom bulb, which propels the venom out from the duct; and a harpoon, which with serves to inject the venom into the prey. Cone snails have a distensible proboscis and when it senses the prey, a single harpoon tooth is transferred from a radular sac to the lumen of the proboscis and therefore propelled for an efficient delivery of the venom (Olivera, 1997). The venom components are stored in the duct by microscopic granules suspended in a fluid; up to 60% of the molecular components in venom are associated with the granular fraction (Jimenez et al., 1983; Marshall et al., 2002). Most studies use the venom extracted out the dissected ducts (dissected venom); however, the actual venom injected into the prey (injected venom) can be obtained for species that prey upon fish (Hopkins et al., 1995).

While the small peptidic components of the venom (conopeptides) have been the focus of intense studies (Halai and Craik, 2009; Han et al., 2008; Lewis, 2009), the larger protein components of Conus venom (conoproteins) have been less comprehensively studied. The dissected Conus venom is known to contain enzymes, such as acetylcholinesterase, proteases, phosphodiesterases (Pali et al., 1979), toxin precursor molecules and other undescribed proteins (Marsh, 1970). Gel electrophoresis analyses indicated that there are proteins that vary widely in molecular weight in the dissected venom of several cone snail species (Cruz et al., 1976). More recent proteomic studies have revealed a wealth of proteins (more than 150 identifiable proteins per species) in the venom ducts of Conus novaehollandiae and Conus victoriae (Safavi-Hemami et al., 2011). 66 proteins were identified in the dissected venom of Conus consors; surprisingly, in the same study, only two proteins were identified in the injected venom of this species (Leonardi et al., 2012). Just as in other venomous animals, larger molecules present in Conus venom can perform a variety of functions, acting as neurotoxins, carrier proteins, or degradative enzymes such as proteases, hyaluronidases and lipases, and in toxin processing (Terlau and Olivera, 2004).

Proteases are degradative enzymes that achieve cellular control of essential biological processes through a highly specific hydrolysis of peptide bonds. In animal venom, proteases exert physiological effects on the prey, such as tissue degradation, which results in more efficient venom diffusion (Lopez-Otin and Overall, 2002). Marsh has shown that proteases are present in the venom of several species of vermivorous cone snails (Marsh, 1971). A protease belonging to the cysteine-rich secretory protein (CRISP) was isolated from the dissected venom of Conus textile (Tex31) (Milne et al., 2003). Tex31 was shown to be capable of cleaving the conotoxin TxVIA from its precursor. However, proteins that belong to the CRISP family, like helothermines, are found in snake and lizard venom and block skeletal and cardiac ryanodine receptors specifically (Lopez-Otin and Overall, 2002; Mackessy, 2002). Proteomic analyses of the venom duct of Conus novaehollandiae identified high abundance of kallikrein-like proteins (Safavi-Hemami et al., 2011). Kallikreins are serine proteases found in animal venom that facilitate the degradation of kinins and fibrinogens on the prey (Asgari et al., 2003). Other proteases were also found in the venom duct of C. victoriae (Safavi-Hemami et al., 2011), such as the aspartyl protease cathepsin-D-like and proline peptidases. Cathepsin D cleaves fibronectin and it breaks drown extracellular matrices (Benes et al., 2008). Proline peptidases are involved in several cellular processes not necessarily related to envenomation (Walter et al., 1980). Proteomics analysis of the dissected venom of C. consors revealed the presence CRISP proteases and M12A peptidases, a class of zinc metalloproteinases that share common features with serralysins, matrix metalloendopeptidases, and snake venom proteases (Bond and Beynon, 1995).

In contrast to the widely documented effects of common venomous animal bites or stings, which manifest as hemorrhage, necrosis and inflammatory reactions, the degradative effects of cone snail venom are largely undescribed. An early study of some vermivorous Conidae found that the venom produces degradative effects in mice, such as tissue necrosis and hemorrhage at the site of the injection (Endean and Rudkin, 1965). Some cone snail stings in humans could lead to subcutaneous abscesses, which can be accompanied by pain, paraesthesia, general malaise, and fever (Veraldi et al., 2011).

Here we describe the distribution of proteases in the injected venom of two piscivorous species, Conus purpurascens and Conus ermineus (Eastern Pacific and Western Atlantic species, respectively), and in the dissected venom of Conus marmoreus (an Indo Pacific molluscivorous species) and Conus virgo (an Indo Pacific vermivorous species). We compare the venom protease content among these cone snail species with different feeding preferences and between dissected and injected venom for C. purpurascens. We show that metalloproteases and serine proteases not only participate in intrinsic venom biosynthesis but might also affect the hemostatic mechanism of the prey, as the injected venom from C. ermineus had fibrinogenolytic effects.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Extraction of dissected venom

Live specimens of all cone snail species here used were kept in aquaria in our laboratory prior to their dissection. The specimens of C. marmoreus and C. virgo were collected at several locations off the Vanuatu archipelago. Specimens of C. purpurascens were collected from several locations off the Pacific Coast of Costa Rica. The animals were sacrificed by placing them in an ice bath. The venom ducts were dissected from 4 specimens of C. marmoreus, 2 specimens of C. virgo and 2 specimens of C. purpurascens. Injected venom was extracted from the specimens of C. purpurascens before their dissected venom extraction (see below). The ducts were separately homogenized using a Dounce homogenizer in 5 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 8 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, and 1 mM MgCl2 at 4 °C. Whole extracts were centrifuged at 10000g for 20 min, at 4 °C, and the resulting pellets were washed three times and re-centrifuged under identical conditions. The supernatants were pooled, lyophilized, and stored at −80 °C until further use.

2.2. Extraction of injected venom

Extraction of injected venom samples of C. purpurascens and C. ermineus were carried out according to the procedure of Hopkins et al. (Hopkins et al., 1995) with modifications (Moller and Mari, 2011). Specimens of C. ermineus were collected from several locations off the South East Florida coast and the corresponding injected venom was extracted as described above.

2.3. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

SDS-PAGE was carried out using NuPAGE-Novex precast 10–20% polyacrylamide gradient tris-glycine gels or 10% polyacrylamide tris-glycine gels. Electrophoretical polypeptide patterns were obtained for the dissected venom samples (40 μg per well) from C. marmoreus and C. virgo, and for the injected venom samples (20 μL per well) from C. purpurascens and C. ermineus. Stock solutions of venom were prepared to maintain the same protein concentration in each well. Pre-stained molecular weight markers were used as standards (Novex, Invitrogen). Proteins were visualized using colloidal coomassie blue staining and silver staining

2.4. SDS-PAGE-gelatin zymograms

For gelatinolytic activity analysis, venom samples were subjected to zymography analysis by using precasted 10% polyacrylamide zymogram gelatin gels (Novex, Invitrogen). Following electrophoresis, gels were washed with 2.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 for a total of 30 min at room temperature to remove SDS. The gels were then placed in incubation buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0 and 5 mM CaCl2) for 30 min at room temperature. Then, the gels were placed in fresh incubation buffer for 18 h at 37 °C to allow proteolysis of the substrate in the gels. Gelatin gels were then rinsed with water and stained with coomassie blue and destained until clear bands became evident.

The gelatinolytic activities of dissected venom samples were determined at various pH values and proteases inhibitors as follow. After electrophoresis, the gel slabs were washed as described above. Subsequently, the gel was washed in distilled water, sliced into strips, and incubated with various solutions. The effect of pH on the gelatinolytic activity was determined as previously described (Veiga et al., 2000) with the following modifications. Each strip was incubated overnight, at 37 °C with 5 mM CaCl2 and 50 mM of either of the following buffers: acetate buffer pH 4.5, succinic buffer pH 5.5, 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid (PIPES) buffer pH 6.5, 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazine-1-ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer pH 7.5, Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.5, ammonium bicarbonate buffer pH 9.5, and 3-(cyclohexylamino)-1-propanesulfonic acid (CAPS) buffer pH 10.5. To measure the effect of different temperatures on the gelatinolytic activity, each strip was incubated overnight with 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.0 containing 5 mM CaCl2 at 4, 10, 25, 30, 37, 50, and 60 °C. Gel strips were also incubated with various protease inhibitors in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8.0 and 5 mM CaCl2 as previously described with modifications (Feitosa et al., 1998). As a control, the whole venom was developed in the absence of protease inhibitors. The following inhibitors were examined: leupeptin (100 μM), iodoacetamide (10 mM), benzamidine (4 mM), aprotinin (2.0 μg/mL), phenyl-methyl-sulphonyl fluoride (PMSF) (1 mM), Nα-tosyl-phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK) (100 μM), Nα-tosyl-lysyl chloromethyl ketone (TLCK) (100 μM), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (10 mM), ethyleneglycoltetraacetic acid (EGTA) (10 mM), and 1,10-phenanthroline (10 mM).

2.5. Evaluaton of the fibrinogenolytic and fibronectinolytic activities of injected cone snail venom

The capability of hydrolyzing fibrinogen and fibronectin by C. purpurascens and C. ermineus injected venom was evaluated by SDS-PAGE (Kumar et al., 2011). Human plasma fibrinogen or fibronectin (20 μg, Sigma) was incubated with 20 μL of injected venom, in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4. Following incubation for 18 h, at 37 °C, a 10 μL aliquot of 4X Laemmli SDS-PAGE sample buffer (Laemmli, 1970) containing 5% β-mercaptoethanol was added to the reaction mixture. Samples were heated at 70 °C for 5 minutes and then analyzed by electrophoresis.

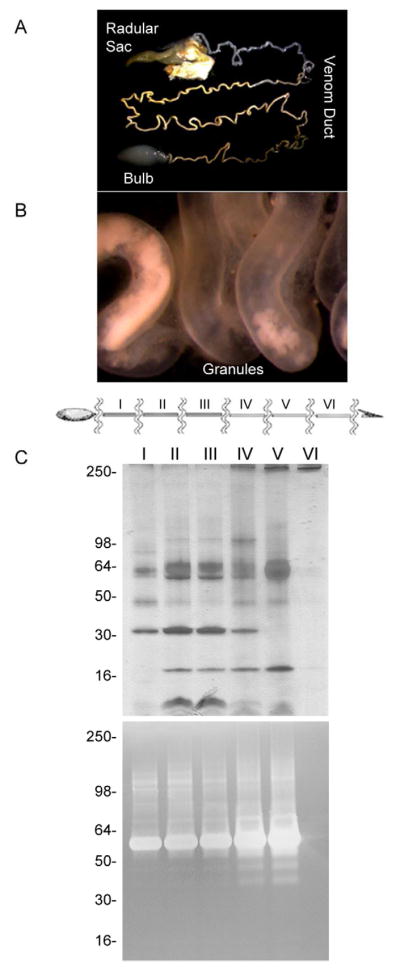

2.6. Protease distribution in the venom duct of C. marmoreus

Venom ducts from C. marmoreus were dissected and placed on an Olympus SZX12 stereomicroscope equipped with a digital camera. Each duct was further divided into equal sized sections from the bulb through the radular sac, and each section was processed separately to obtain a crude venom extract, which was lyophilized and stored at −80 °C until further use. Sections were assigned by roman numerals (I–VI) beginning at the bulb.

3. Results

3.1. SDS-PAGE separation and gelatinolytic activity of cone snail venom

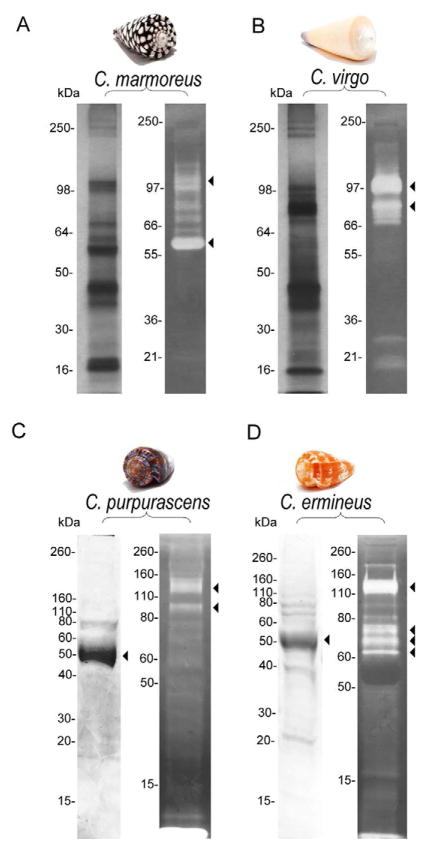

To show the presence of conoproteins and conoproteases in injected venom, we performed SDS-PAGE and gelatin zymograms using the injected venom of two piscivorous species, C. purpurascens and C. ermineus. The most prominent protein bands in these venoms migrated at 55 kDa (M+ = 61 kDa, MALDI-TOF MS, data not shown) in both samples (Fig. 1A and 1B, left). These bands correspond to Hyal-P and Hyal-E respectively (Moller et al, manuscript in preparation), which are hyaluronidases known to be present in the injected venom of fish-hunting cone snail species (Violette et al., 2012). Less intense bands at higher and lower molecular masses were also detected (Fig. 1A and B, left). The proteolytic profile was different between both venom samples, which contained major protease bands migrating at ~ 90 and 150 kDa for C. purpurascens (Fig. 1A, right) and at ~ 65, 70, 75 and 150 kDa for C. ermineus (Fig. 1B, right). These results clearly show that conoproteins and conoproteases are injected into the prey and that they are likely to exert envenomation and commence tissue degradation on the prey.

Figure 1. SDS-PAGE (left) and gelatin zymogram (right) of different cone snail venom samples.

Injected venom samples from C. purpurascens (A), C. ermineus (B) and dissected venom samples from C. marmoreus (C) and C. virgo (D). Arrows indicate principal SDS-PAGE bands and gelatinolytic activity where protease activity appears as clear bands against a dark background.

The dissected venom samples of C. marmoreus and C. virgo were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1C and D, left). Multiple protein bands with molecular masses ranging from 16 to > 250 kDa were observed. C. marmoreus and C. virgo showed different protein profiles, demonstrating protein composition variability between these two species with different feeding preferences. Gelatin zymograms of these venom samples showed bands with variable proteolytic activities (Fig. 1C and D, right). The major gelatinolytic activity in C. marmoreus venom was found at ~ 60 kDa (Fig. 1C, right). However, other protein bands possessing gelatinolytic activity were detected at higher molecular weights. In particular, proteolytic bands of medium intensity were observed at ~ 97–100 kDa. C. virgo dissected venom contained major bands with gelatinolytic activities of between 80 and 97 kDa (Fig. 1D, right), in addition to other minor proteolytic bands at lower and higher apparent molecular sizes.

3.2. Comparison between dissected and injected venom by SDS-PAGE and gelatinolytic activity

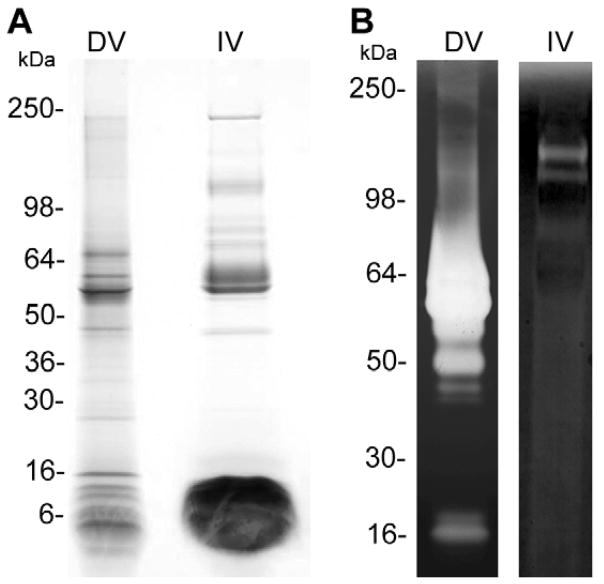

SDS-PAGE and gelatin zymography analysis of the dissected and injected venom of C. purpurascens revealed very distinct profiles (Fig. 2). The dissected venom has more protein components than its corresponding injected venom counterpart (Fig. 2A). The injected venom shows massive band below than 16 kDa, which contains low molecular weight proteins and conopeptides. Similarly, the gelatinolytic activity is greater for the dissected venom than for injected venom (Fig. 2B). The most prominent proteolytic activity is between 50 and 60 kDa, which is not present in the injected venom. These results show that some of the proteins and proteases present in the dissected venom are not for envenomation purposes; instead, they might be part of the metabolic machinery of the cells in the duct or are they involved in toxin processing and maturation.

Figure 2. Comparison between dissected and injected venom of C. purpurascens.

A. SDS-PAGE and B. Gelatinolytic activity. Analysis of 20 μL of injected venom (IV) and 25 μg of dissected venom (DV) by SDS-PAGE (A) and by gelatin zymograms (B).

3.3. Effect of pH and temperature on the gelatinolytic activity of the proteases from C. marmoreus and C. virgo

The proteolytic activity of the dissected venom from C. marmoreus and C. virgo was evaluated at different pH values by zymograms on gelatin (Fig. 1S). For C. marmoreus, the pH for optimal conoprotease activity was 8.5 (Fig. 1S A). As shown in Fig. 2, several proteolytic bands between 60–64 kDa were activated at pHs between 6.5 and 8.5. However, their proteolytic activity decreased at higher pHs (Fig. 1S A). Two bands with apparent molecular masses of 98 and 100 kDa also exhibited optimal gelatinolytic activity at pH 8.5; however, significant enzymatic activity was maintained at pH 10.5. Similarly, proteolytic bands of 28 and 32 kDa also showed optimal activity at pH 8.5, and remained active until pH 10.5 (Fig. 1S A). The venom from C. virgo started showing proteolytic bands with apparent molecular masses of 28, 80, 97 and 150 kDa at pH ≥ 6.5 (Fig. 1S B); however, for all these bands the optimal activity was at pH 9.5 (Fig. 1S B). Proteolytic activity was minimal at acidic pH for these venom samples.

The temperature effect on the proteolytic activity in the venom of C. marmoreus and C. virgo was determined by zymograms on gelatin, by incubating the gel strips at temperatures from 4 to 60 °C. The optimal temperature was 37 °C (Fig. 2S), although significant gelatinolytic activity was observed at lower and higher temperatures (Fig. 2S).

3.3. Effect of protease inhibitors on the gelatinolytic activity of conoproteases

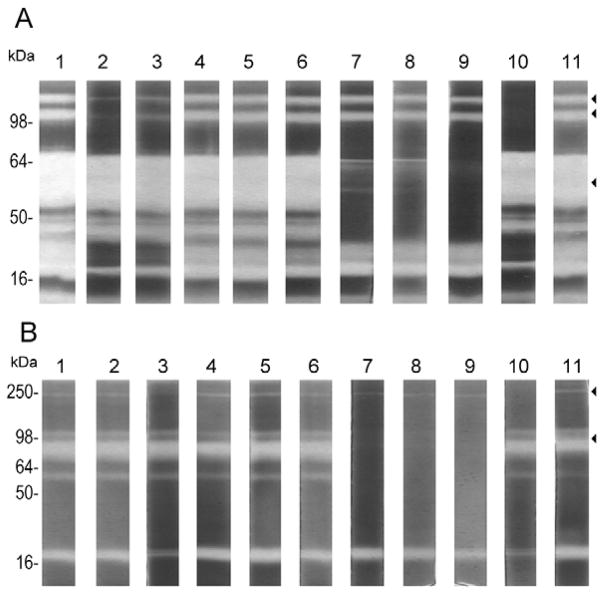

The inhibitory profile of the proteases from the venom of C. marmoreus and C. virgo, were determined using gelatin SDS-PAGE gels incubated protease inhibitors (Fig. 3). For the C. marmoreus sample, EDTA, EGTA and 1,10-phenanthroline inhibited the broad band with gelatinolytic activity that migrated with a molecular mass between 60–64 kDa, which indicated the presence of metalloproteases in this band (Fig. 3A, lanes 7, 8 and 9). Additionally, benzamidine, aprotinin, and leupeptin inhibited the proteolytic activity of two consecutive bands with molecular masses of 98 and 100 kDa (Fig. 3A, lanes 2, 3 and 10). Benzamidine and aprotinin are inhibitors for serine proteases, whereas leupeptin is a broad-profile cysteine and serine protease inhibitor. These results suggest the presence of serine and metalloproteases in the dissected venom from C. marmoreus. However, no inhibition was observed with PMSF, TPCK, and TLCK (Fig. 3, lanes 4, 5 and 6 respectively), indicating that none of these conoproteases are trypsin-like, chymotrypsin-like or elastase-like serine proteases. Iodoacetamide, a known cysteine protease inhibitor, had no effect on the proteolytic activity of these conoproteases (Fig. 3, lane 11). For the dissected venom of C. virgo, the band with gelatinolytic activity with a molecular mass of 80 kDa was inhibited with all metalloprotease inhibitors that were used (Fig. 3B, lanes 7, 8 and 9). A weak protease band of molecular mass of 250 kDa was inhibited in the presence of leupeptin and the serine protease inhibitors benzamidine, aprotinin, but not by TPCK, TLCK or PMSF (Fig. 3B). These results indicate that the venoms of C. marmoreus and C. virgo contain active metalloproteases and serine proteases.

Figure 3. Effect of protease inhibitors on the gelatinolytic activity of dissected venom samples.

Protease inhibitors were used to determine the type of proteases present in the venom. SDS-PAGE-gelatin gels containing separated products of the dissected venom samples from C. marmoreus (A) and C. virgo (B) were incubated in the presence of inhibitors of serine-, metallo- and cysteine-proteases. Lane assignments are as follows: Whole dissected venom (lane 1), dissected venom incubated with: benzamidine (lane 2), aprotinin (lane 3), PMSF (lane 4), TPCK (lane 5), TLCK (lane 6), EDTA (lane 7), EGTA (lane 8), 1,10-phenanthroline (lane 9), leupeptin (lane 10), iodoacetamide (lane 11). The disappearance or decrease in intensity of the proteolytic bands show gelatinolytic inhibition and indicate the protease type.

The proteolytic activities of the injected venom from C. purpurascens and C. ermineus were reduced in the presence of the metalloprotease inhibitors, 1,10-phenanthroline and EDTA, and the serine protease inhibitor, benzamidine, but not by TPCK (Fig. 4). These results indicate that the injected venom samples contain metalloproteases and serine proteases, which co-migrated on SDS-PAGE-gelatin zymograms. These proteases may play a role in envenomation by these piscivorous species, and that they are likely to be involved in local and systemic damage of the prey.

Figure 4. Effects of protease inhibitors on the gelatinolytic activity of injected venom.

Proteases inhibitors were used to determine gelatinolytic activities of injected venom from C. purpurascens (A) and C. ermineus (B). Lane assignments are as follows: injected venom only (lane 1), injected venom incubated with metalloproteases inhibitors: 1,10-phenanthroline (lane 2), EDTA (lane 3), and serine protease inhibitors: benzamidine (lane 4), TPCK (lane 5).

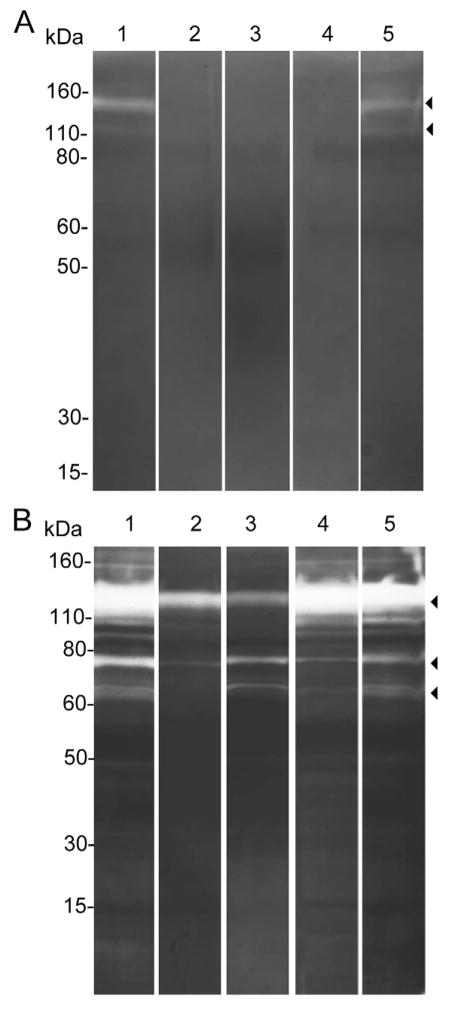

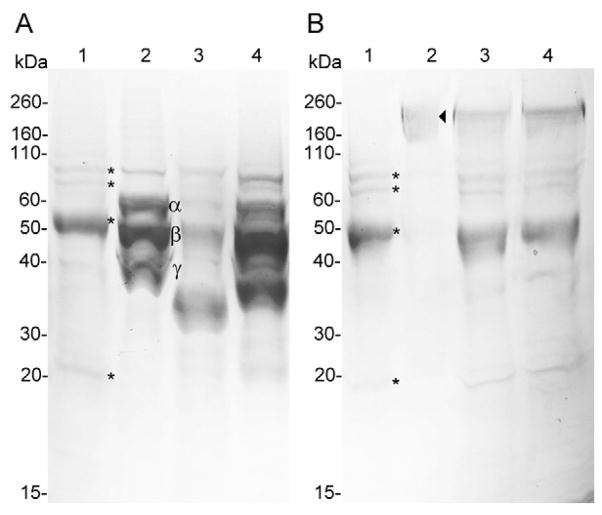

3.4. Evaluation of fibrinogenolytic and fibronectinolytic activities of the injected cone snail venom samples

In order to evaluate the potential effect of proteases of the injected venom of C. purpurascens and C. ermineus in the prey, we tested whether the injected venom of these cone snails could degrade fibrinogen and fibronectin. The activities of the injected venom on fibrinogen and fibronectin were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 5). Only the injected venom from C. ermineus was capable of degrading the Aα (63 kDa), Bβ (56 kDa), and γ (47 kDa) chains of fibrinogen after 18 h of incubation (Fig. 5A, lane 3). This fibrinogenolytic activity was completely blocked with EDTA (Fig. 5A, lane 4), indicating that the metalloproteases in this venom sample are responsible for the fibrinogenolytic activity. No degradation of fibronectin was observed in the presence of the injected venom from C. ermineus (Fig. 6B). No fibrinogenolytic or fibronectinolytic activities were observed for the injected venom from C. purpurascens (Fig. 3S). We found that the dissected venom from C. marmoreus and C. virgo clotted fibrinogen in vitro thus hampering SDS-PAGE analysis (data not shown).

Figure 5. Evaluation of the fibrinogenolytic and fibronectinolytic activities of injected venom from C. ermineus.

Analysis by SDS-PAGE of the degradation of fibrinogen (A) and fibronectin (B) by C. ermineus injected venom. (*) denotes injected venom components. Fibrinogen subunits Aα (~63 kDa), Bβ (~56 kDa), and γ (~47 kDa) fibronectin subunit (~230–250 kDa) were labeled (◂). Lanes assignments are as follows: only injected venom (lane 1), fibrinogen/fibronectin (lane 2), injected venom and fibrinogen/fibronectin (lane 3), injected venom, fibrinogen/fibronectin and EDTA (lane 4).

Figure 6. Microscopy and protein profiling of venom duct sections.

A venom duct from C. marmoreus was imaged under a microscope from the bulb to the radular sac (A). The yellow granules can be visualized at 30X magnification (B). The venom duct was further divided in equal size sections assigned by roman numbers (I–VI) (C). Each duct part was processed separately to obtain a local whole venom extraction and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and gelatin-zymography (D).

3.5. Distribution of proteases along the venom duct of C. marmoreus

Dissected venom ducts from C. marmoreus were directly observed under a microscope (Fig. 6). The venom duct showed different colors, ranging from dark orange to yellowish and clear, going from the bulb to the radular sac (Fig. 6A). Under 30X magnification we observed a yellowish granular material floating in a clear fluid or lumen (Fig. 6B). These granules were more abundant near the bulb region (proximal duct) while a clear fluid was observed toward the radular sac (distal duct) with practically no granular material. SDS-PAGE separations and SDS-PAGE-gelatin zymograms of identically sized sections of the venom duct from C. marmoreus (sections I–VI) revealed that proteins and proteases were also associated with these granules (Fig. 6C). The protein content and the proteolytic activities increased towards the distal duct (section V). However, no protein bands or proteolytic activities were observed in the very distal section (section VI), which corresponded to the section with practically no granular material. Additionally, a clear variability of the protein composition was observed from the proximal to the distal duct sections, particularly, when section I was compared to section V, where some protein bands increased and other bands decreased (Fig. 6C). The venom duct sections of C. virgo showed similar results (data not shown).

4. Discussion

Here we report the variations in expression of conoproteins and conoproteases in the venom of cone snail species with different prey preferences. Conoproteins have been found in the dissected venom of several cone snail species; however, we show that proteins and active proteases are present in injected venom, implicating them in the envenomation mechanism used by cone snails. This finding resembles the biochemical strategy used by other predatory venomous animals, as proteases have been described in animal venoms and their physiological activities have been well documented (Devaraja et al., 2011; Kini, 2005; Li et al., 2005). We found conoproteases with gelatinolytic activities in the injected venom, as well as in the dissected venom of cone snail species studied here. These proteases seem to be well adapted to the conditions of the marine environment that they inhabit, since the conoproteases in the dissected venom from C. marmoreus and C. virgo were active at broad pH and temperature ranges. They might remain active regardless of environmental conditions to which they might be exposed.

Protease inhibitor analysis showed the presence of metalloproteases and serine proteases in the venom of cone snails. The inhibitory sensitivity to the metal chelators EDTA, EGTA and 1,10-phenanthroline indicated the presence of metalloproteases in the injected venom of C. purpurascens and C. ermineus, and in the dissected venom of C. marmoreus and C. virgo. Serine proteases were observed in the dissected venom samples of C. marmoreus and C. virgo, as determined by their sensitivity to benzamidine, aprotinin, and leupeptin. Since metalloproteases were observed in both, injected and dissected venom, they are probably involved in venom processing and for envenomation purposes.

Fibrinogenolytic and fibronectinolytic activities are among the effects commonly associated with venom metalloproteases. The injected venom from C. ermineus showed the ability to degrade fibrinogen subunits but not fibronectin. In some species, snake venom proteases can be proteolytic on fibrinogen and fibronectin. However, in other snake species, separate enzymes are needed to cleave fibrinogen and fibronectin (Markland, 1998). EDTA abolished the degradation of fibrinogen by C. ermineus venom indicating metalloprotease involvement in this process.

Serine and metalloproteases are well described in several animal venoms, particularly in snake species (Kini, 2005; Mackessy, 2002; Matsui et al., 2000). Although venom proteases contribute to the prey digestion, they might have other physiological effects, such as changes of the hemostatic or nervous system. Serine proteases and metalloproteases are also found in the venom of stingrays, jellyfish and sea snakes (He et al., 2007; Kumar et al., 2011; Le et al., 2002). Marine venom proteases are likely to play significant roles in the pathogenesis of venom-induced local tissue damage and toxicity. Our findings suggest that conoproteases are likely to have an effect on the hemostatic system of the prey.

Since there are several possible biological roles for proteases in Conus venom, it will be desirable to perform a detailed molecular characterization of these enzymes to determine their specific biological roles and classification. Attempts to use bottom-up proteomics techniques led to no significant sequence matches (data not shown). Even in cases where transcriptomic data is available, only a very limited number of proteins (hyaluronidases and actinoporin) could be identified in the injected venom of Conus consors (Leonardi et al., 2012). Furthermore, as data on transcriptomes and genomes of Conus species is starting to emerge, poor sequence homology between specific conoproteins across different species hampers a generic proteomic approach. Case on hand, the major protein in the venom of C. purpurascens and C. ermineus are the Hyaluronises Hyal-P and Hyal-E respectively. The MS/MS spectra of the trypsinized peptides of these enzymes from the injected venom of C. purpurascens show poor matching with Hyal-Cn (data not shown), a fully characterized Hyaluronidase from the injected venom of Conus consors (Violette et al., 2012). However, we can foresee proteomics approaches revealing the molecular identities of the proteases here described, once the corresponding transcriptomic data become available.

When evaluating the molecular content of Conus venom is important to consider the differences between dissected vs. injected venom. Regarding the conopeptide composition, it is well established that injected venom differs significantly from dissected venom (Bingham et al., 1996; Dutertre et al., 2010). Little correlation was found between the conopeptides in the venom duct and those obtained after “milking” the same live cone snail (injected venom) (Dutertre et al., 2010). Regarding the conoprotein composition, our results show that there is correspondence between the proteins in the dissected and injected venom of the same specimen of C. purpurascens. However, gelatinolytic activity was greater on dissected than the injected venom; this supports the notion that some of the proteases might be for venom molecular processing and maturation. Dissected venom is expected to show higher proteolytic activity than injected venom as it contains the cellular metabolic machinery of the venom duct and venom processing enzymes, whereas injected venom only contains the purified mature protein arsenal destined for prey envenomation. Likewise, more protein complexity and stronger gelatinolytic activity in the dissected venom of C. marmoreus and C. virgo than in the injected venom of C. ermineus and C. purpurascens.

A close examination of the venom duct revealed a heterogeneous distribution of granules floating in the lumen. Marshall et al. (Marshall et al., 2002) described the presence and distribution of these granules originally in the venom duct from C. californicus. They proposed that there are ultrastructural and functional differences between the proximal and distal portions of the venom duct, where conopeptides are synthesized, assembled, packed inside the granules and discharged by holocrine secretion. We found that proximal and distal portions of the venom duct differ in protein and protease content, indicating that conoproteins and conoproteases are packed into these granules. It has been proposed that there is a narrow passageway between the venom duct and the pharynx through which the venom passes prior injection (Marshall et al., 2002). This passageway is a branching channel that narrows to a width of 10 μm, suggesting that mechanical granule breakdown occurs.

The different protein and proteolytic profiles obtained from different segments of the venom duct from C. marmoreus and C. virgo suggest a complex mechanism for venom processing that involves differential protease participation in venom maturation. It has been shown that small peptidic venom components (Marshall et al., 2002; Tayo et al., 2010) and the mRNA that encodes for conotoxin superfamilies (Garrett et al., 2005) are expressed differentially along the venom duct. However, our findings appear to differ to RT-PCR results that show strong expression of O-superfamily conotoxin precursors and PDI in the distal region of the venom duct of C. textile (Garrett et al., 2005). By way of contrast, M, T, and to some extent P and A conotoxin precursors, are weakly expressed in this region, just as the proteins and proteases of C. marmoreus and C. virgo. However, caution must be exercise as this comparison is done between venom ducts split differently. Nevertheless, venom processing and maturation is highly heterogeneous with specialized cellular machinery and exquisite specificity along the venom duct that eventually leads to the production of the mature venom.

The venom of the four cone snail species that we analyzed varied in protein and protease composition regarding their molecular weights, gelatinolytic and fibrinogenolytic activities. Intraspecies and interspecies variation in Conus venom, particularly conopeptide variability, is well known (Davis et al., 2009; Duda et al., 2009; Dutertre et al., 2010; Jakubowski et al., 2005; Rivera-Ortiz et al., 2011). Conotoxin genes have evolved via a mechanism of positive selection and diversification by environmental and behavioral pressure. This could also be the case for conoproteins, which are likely to vary among species, particularly for species with different feeding preferences and environmental locations. Although C. purpurascens and C. ermineus belong to the same clade, the fibrinogenolytic activity was found only in C. ermineus. The difference in the proteolytic components of these two related species may be due to environmental pressure. Both cone snails are piscivorous, however, the C. purpurascens used for this study were found in intertidal areas and in between rocks in the Eastern Pacific coast of the Americas (Moller and Mari, 2011), whereas the C. ermineus specimens were collected in deeper waters (10–40m) in the East coast of Florida (Rivera-Ortiz et al., 2011).

In conclusion, we found proteins and proteases with specific proteolytic activity in the injected venom and dissected venom of four cone snail species. The biochemical and functional characterization of conoproteins is significant from many points of view. These larger venom components are complementary to the conopeptides in the mechanism of envenomation use by these remarkable marine predators. Additionally, conoproteins are pivotal to venom processing and other molecules that act like toxins or exacerbate toxin activities. Conoproteins expand the complexity and molecular reach of cone snail venom. Proteases are valuable tools in their own right as they are used in diagnostic and clinical treatments (Koh et al., 2006; Marder and Novokhatny, 2010). Finding novel proteases in marine venomous animals can augment the potential applications of these enzymes.

Supplementary Material

The gelatinolytic activities of dissected venom of C. marmoreus (A) and C. virgo (B) were measured at different pH values between 4.5 and 10.5. Proteolytic bands can be observed above pH 6.5. Arrows indicated gelatinolytic activities that changed with pH.

The effect of different temperatures between 4 and 60 °C on the gelatinolytic activity was tested with dissected venom samples of C. marmoreus (A) and C. virgo (B). Gelatinolytic activity can be observed in a wide range of temperatures. The maximal activity was observed at 37 °C.

Analysis by SDS-PAGE of the degradation of fibrinogen (A) and fibronectin (B) by C. purpurascens injected venom. (*) denotes injected venom components. Fibrinogen subunits Aα (~63 kDa), Bβ (~56 kDa), and γ (~47 kDa) fibronectin subunit (~230–250 kDa) were labeled (◂). Lanes assignments are as follows: only injected venom (lane 1), fibrinogen/fibronectin (lane 2), injected venom and fibrinogen/fibronectin (lane 3), injected venom, fibrinogen/fibronectin and EDTA (lane 4).

Highlights.

The proteolytic enzymes in the venom of four cone snails species were evaluated

All venom samples displayed proteolytic activity on gelatin

Fibrinogenolytic activity was found in the venom of C. ermineus

Protein expression was differential along the venom duct of C. marmoreus

Conoproteases have a complex participation in venom biosynthesis.

Conoproteases participates in venom processing and envenomation of the prey.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Herminsul Cano for his help in extracting the venom samples; Prof. Anton Oleinik for his assistant with the microscopy; Mari Heghinian and Dr. Helena Safavi-Hemani for proofreading the manuscript and providing useful suggestions. This work was partially funded by the Florida Sea Grant Program (Grant R/LR-MB-28) and the NIH (Grant NS066371-01).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Asgari S, Zhang GM, Zareie R, Schmidt O. A serine proteinase homolog venom protein from an endoparasitoid wasp inhibits melanization of the host hemolymph. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;33:1017–1024. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(03)00116-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benes P, Vetvicka V, Fusek M. Cathepsin D - Many functions of one aspartic protease. Critical Reviews in Oncology Hematology. 2008;68:12–28. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham J-P, Jones A, Lewis RJ, Andrews PR, Alewood PF. Conus venom peptides (conopeptides): Interspecies, intraspecies and within-individual variation revealed by ion-spray mass spectrometry. Biochemical Aspects of Marine Pharmacology. 1996:13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Bond JS, Beynon RJ. Then astacin family of metalloendopeptidases. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1247–1261. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz LJ, Corpus G, Olivera BM. A preliminary study of Conus venom protein. Veliger. 1976;18:302–308. [Google Scholar]

- Davis J, Jones A, Lewis RJ. Remarkable inter- and intra-species complexity of conotoxins revealed by LC/MS. Peptides. 2009;30:1222–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaraja S, Girish KS, Gowtham YNJ, Kemparaju K. The Hag-protease-II is a fibrin(ogen)ase from Hippasa agelenoides spider venom gland extract: Purification, characterization and its role in hemostasis. Toxicon. 2011;57:248–258. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda TF, Jr, Chang D, Lewis BD, Lee T. Geographic variation in venom allelic composition and diets of the widespread predatory marine gastropod Conus ebraeus. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6245. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutertre S, Biass D, Stocklin R, Favreau P. Dramatic intraspecimen variations within the injected venom of Conus consors: An unsuspected contribution to venom diversity. Toxicon. 2010;55:1453–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endean R, Rudkin C. Further studies of the venom of Conidae. Toxicon. 1965;69:225–249. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(65)90021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feitosa L, Gremski W, Veiga SS, Elias M, Graner E, Mangili OC, Brentani RR. Detection and characterization of metalloproteinases with gelatinolytic, fibronectinolytic and fibrinogenolytic activities in Brown spider (Loxosceles intermedia) venom. Toxicon. 1998;36:1039–1051. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(97)00083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett JE, Buczek O, Watkins M, Olivera BM, Bulaj G. Biochemical and gene expression analyses of conotoxins in Conus textile venom ducts. Biochem Biophysical Res Comm. 2005;328:362–367. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halai R, Craik DJ. Conotoxins: natural product drug leads. Nat Prod Rep. 2009;26:526–536. doi: 10.1039/b819311h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han TS, Teichert RW, Olivera BM, Bulaj G. Conus venoms - A rich source of peptide-based therapeutics. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2008;14:2462–2479. doi: 10.2174/138161208785777469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Chen S, Gu J. Identification and characterization of Harobin, a novel fibrino(geno)lytic serine protease from a sea snake (Lapemis hardwickii) FEBS Letters. 2007;581:2965–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins C, Grilley M, Miller C, Shon KJ, Cruz LJ, Gray WR, Dykert J, Rivier J, Yoshikami D, Olivera BM. A new family of Conus peptides targeted to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22361–22367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.38.22361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski JA, Kelley WP, Sweedler JV, Gilly WF, Schulz JR. Intraspecific variation of venom injected by fish-hunting Conus snails. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:2873–2883. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez EC, Olivera BM, Cruz LJ. Localization of enzymes and possible toxin precursors in granules from Conus striatus venom. Toxicon Suppl. 1983;3:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Kini RM. Serine proteases affecting blood coagulation and fibrinolysis from snake venoms. Pathophysiology of Haemostasis and Thrombosis. 2005;34:200–204. doi: 10.1159/000092424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh DCI, Armugam A, Jeyaseelan K. Snake venom components and their applications in biomedicine. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:3030–3041. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6315-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar KR, Vennila R, Kanchana S, Arumugam M, Balasubramaniam T. Fibrinogenolytic and anticoagulant activities in the tissue covering the stingers of marine stingrays Dasyatis sephen and Aetobatis narinari. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2011;31:464–471. doi: 10.1007/s11239-010-0537-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during assembly of head bacteriophage-T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le MT, Vanderheyden PML, Baggerman G, Broeck JV, Vauquelin G. Formation of angiotensin-(1–7) from angiotensin II by the venom of Conus geographus. Regulatory Peptides. 2002;105:101–108. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(02)00005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi A, Biass D, Kordis D, Stocklin R, Favreau P, Krizaj I. Conus consors snail venom proteomics proposes functions, pathways, and novel families involved in tts venomic system. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:5046–5058. doi: 10.1021/pr3006155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis RJ. Conotoxins: molecular and therapeutic targets. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2009;46:45–65. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-87895-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CP, Yu HH, Liu S, Xing RE, Guo ZY, Li PC. Factors affecting the protease activity of venom from jellyfish Rhopilema esculentum Kishinouye. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:5370–5374. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Otin C, Overall CM. Protease degradomics: A new challenge for proteomics. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2002;3:509–519. doi: 10.1038/nrm858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackessy SP. Biochemistry and pharmacology of colubrid snake venoms. J Toxic - Toxin Rev. 2002;21:43–83. [Google Scholar]

- Marder VJ, Novokhatny V. Direct fibrinolytic agents: biochemical attributes, preclinical foundation and clinical potential. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:433–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markland FS. Snake venom fibrinogenolytic and fibrinolytic enzymes: An updated inventory - On behalf of the registry of exogenous hemostatic factors of the scientific and standardization committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Thromb Haemost. 1998;79:668–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh H. Preliminary studies of venoms of some vermivorous Conidae. Toxicon. 1970;8:271–277. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(70)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh H. Caseinase activity of some vermivorous cone shell venoms. Toxicon. 1971;9:63–67. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(71)90044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall J, Kelley WP, Rubakhin SS, Bingham JP, Sweedler JV, Gilly WF. Anatomical correlates of venom production in Conus californicus. Biol Bull. 2002;203:27–41. doi: 10.2307/1543455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsui T, Fujimura Y, Titani K. Snake venom proteases affecting hemostasis and thrombosis. Biochim Biophys Acta - Protein Structure and Molecular Enzymology. 2000;1477:146–156. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milne TJ, Abbenante G, Tyndall JDA, Halliday J, Lewis RJ. Isolation and characterization of a cone snail protease with homology to CRISP proteins of the pathogenesis-related protein superfamily. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31105–31110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304843200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller C, Mari F. 9.3 KDa Components of the injected venom of Conus purpurascens define a new five-disulfide conotoxin framework. Biopolymers. 2011;96:158–165. doi: 10.1002/bip.21406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivera BM. E.E Just lecture, 1996 Conus venom peptides, receptor and ion channel targets, and drug design: 50 million years of neuropharmacology. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:2101–2109. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.11.2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pali ES, Tangco OM, Cruz LJ. The venom duct of Conus geographus: some biochemical and histologic studies. Bull Philip Biochem Soc. 1979;2:30–51. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Ortiz JA, Cano H, Mari F. Intraspecies variability and conopeptide profiling of the injected venom of Conus ermineus. Peptides. 2011;32:306–316. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safavi-Hemami H, Siero WA, Gorasia DG, Young ND, MacMillan D, Williamson NA, Purcell AW. Specialisation of the venom gland proteome in predatory cone snails reveals functional diversification of the conotoxin biosynthetic pathway. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:3904–3919. doi: 10.1021/pr1012976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tayo LL, Lu B, Cruz LJ, Yates JR., 3rd Proteomic analysis provides insights on venom processing in Conus textile. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:2292–2301. doi: 10.1021/pr901032r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terlau H, Olivera BM. Conus venoms: a rich source of novel ion channel-targeted peptides. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:41–68. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veiga SS, da Silveira RB, Dreyfuss JL, Haoach J, Pereira AM, Mangili OC, Gremski W. Identification of high molecular weight serine-proteases in Loxosceles intermedia (brown spider) venom. Toxicon. 2000;38:825–839. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(99)00197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veraldi S, Violetti SA, Serini SM. Cutaneous abscess after Conus textile sting. J Travel Med. 2011;18:210–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2010.00498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violette A, Leonardi A, Piquemal D, Terrat Y, Biass D, Dutertre S, Noguier F, Ducancel F, Stocklin R, Krizaj I, Favreau P. Recruitment of glycosyl hydrolase proteins in a cone snail venomous arsenal: further insights into biomolecular features of Conus venoms. Mar Drugs. 2012;10:258–280. doi: 10.3390/md10020258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter R, Simmons WH, Yoshimoto T. Proline specific endopeptidases and exopeptidases. Mol Cell Biochem. 1980;30:111–127. doi: 10.1007/BF00227927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The gelatinolytic activities of dissected venom of C. marmoreus (A) and C. virgo (B) were measured at different pH values between 4.5 and 10.5. Proteolytic bands can be observed above pH 6.5. Arrows indicated gelatinolytic activities that changed with pH.

The effect of different temperatures between 4 and 60 °C on the gelatinolytic activity was tested with dissected venom samples of C. marmoreus (A) and C. virgo (B). Gelatinolytic activity can be observed in a wide range of temperatures. The maximal activity was observed at 37 °C.

Analysis by SDS-PAGE of the degradation of fibrinogen (A) and fibronectin (B) by C. purpurascens injected venom. (*) denotes injected venom components. Fibrinogen subunits Aα (~63 kDa), Bβ (~56 kDa), and γ (~47 kDa) fibronectin subunit (~230–250 kDa) were labeled (◂). Lanes assignments are as follows: only injected venom (lane 1), fibrinogen/fibronectin (lane 2), injected venom and fibrinogen/fibronectin (lane 3), injected venom, fibrinogen/fibronectin and EDTA (lane 4).