Abstract

Parkinson's disease is characterized by a progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra zona compacta, and in other sub-cortical nuclei associated with a widespread occurrence of Lewy bodies. The cause of cell death in Parkinson's disease is still poorly understood, but a defect in mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and enhanced oxidative and nitrative stresses have been proposed. We have studied controlwt (C57B1/6), metallothionein transgenic (MTtrans), metallothionein double gene knock (MTdko), α-synuclein knock out (α-synko), α-synuclein–metallothionein triple knock out (α-syn–MTtko), weaver mutant (wv/wv) mice, and Ames dwarf mice to examine the role of peroxynitrite in the etiopathogenesis of Parkinson's disease and aging. Although MTdko mice were genetically susceptible to 1, methyl, 4-phenyl, 1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) Parkinsonism, they did not exhibit any overt clinical symptoms of neurodegeneration and gross neuropathological changes as observed in wv/wv mice. Progressive neurodegenerative changes were associated with typical Parkinsonism in wv/wv mice. Neurodegenerative changes in wv/wv mice were observed primarily in the striatum, hippocampus and cerebellum. Various hallmarks of apoptosis including caspase-3, TNFα, NFκB, metallothioneins (MT-1, 2) and complex-1 nitration were increased; whereas glutathione, complex-1, ATP, and Ser(40)-phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase, and striatal 18F-DOPA uptake were reduced in wv/wv mice as compared to other experimental genotypes. Striatal neurons of wv/wv mice exhibited age-dependent increase in dense cored intra-neuronal inclusions, cellular aggregation, proto-oncogenes (c-fos, c-jun, caspase-3, and GAPDH) induction, inter-nucleosomal DNA fragmentation, and neuro-apoptosis. MTtrans and α-Synko mice were genetically resistant to MPTP-Parkinsonism and Ames dwarf mice possessed significantly higher concentrations of striatal coenzyme Q10 and metallothioneins (MT 1, 2) and lived almost 2.5 times longer as compared to controlwt mice. A potent peroxynitrite ion generator, 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1)-induced apoptosis was significantly attenuated in MTtrans fetal stem cells. These data are interpreted to suggest that peroxynitrite ions are involved in the etiopathogenesis of Parkinson's disease, and metallothionein-mediated coenzyme Q10 synthesis may provide neuroprotection.

Keywords: Metallothionein double gene knockout mice, Metallothionein transgenic mice, α -synuclein knockout mice, Homozygous weaver mutant mice (WMhomo), Ames dwarf mice, Fetal stem cell transplantation, 18F-DOPA, MicroPET imaging, Parkinson's disease

1. Introduction

Zinc-containing neurons in the brain are a subclass of glutamatergic neurons, which are found predominantly in the telencephalon. These neurons store zinc in their presynaptic terminals and release it by a calcium-dependent mechanism. These “vesicular” pools of zinc are viewed as endogenous modulators of ligand-gated and voltage-gated ion channels.

The term metallothionein (MTs) refers to a low-molecular-weight metal-binding protein (Mr=6000–7000) that has unusual biochemical characteristics, such as a high content of cysteine (25–30%), large proportions of serine and lysine (12–18%), and complete absence of histidine and aromatic amino acids such as tyrosine and phenylalanine. The precise functions of metallothioneins, which may vary in different tissues and organisms, have not been established. However, evidence indicates that the hepatic and renal metallothioneins are involved primarily in metal detoxification [15], whereas the brain metallothionein isoforms I–III participate in the homeostasis of essential trace metals, such as zinc, and in scavenging free radicals caused by oxidative stress. In addition to scavenging free radicals, metallothionein isoforms exert their neuroprotective effects, in part, by enhancing the concentration of ubiquinol from ubiquinone [11,13–15].

A mutation, by definition, is a change in gene sequence and may be associated with a specific human disease. Genetically engineered mice are produced by induced mutations, including mice with transgenes, mice with targeted mutations (“knockouts”), and mice with retroviral or chemically induced mutations. Transgenic mice possess a segment of foreign DNA that is inserted in the host cell genome via pronuclear microinjection (non-homologous recombination), via infection with a retroviral vector, or in some situations via homologous recombination. Gene knockout mice are prepared by first introducing gene disruptions, replacements, or duplications into embryonic stem (ES) cells by homologous recombination. Genetically modified ES cells are microinjected in the host embryos at the eight-cell blastocyst stage. The embryos are then introduced in the pseudo-pregnant females that bear chimeric progeny. The chimeric progeny that carry the knockout gene in their germ line are subsequently bred to establish the gene knockout mice. Chemically induced mutations are produced by mutagens, such as ethyl–nitrosourea (ENU), which induces point mutations. ENU mutation is induced by treating male mice with ENU, and then breeding is performed with untreated females. The progeny are screened for phenotypes of interest carrying point mutations by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of tail DNA. Detailed information and research applications for different genetically engineered mice are now available on the JAX® Mice Database.

Various experimental models have been proposed to explore basic molecular mechanisms of neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease (PD) [2,8,18]; however, an appropriate animal model of PD remains unavailable. Like any other experimental model, genetically engineered animals have limitations. On occasions, they do not breed well, or their growth potential may be impaired due to a compromised immune system. Irrespective of these limitations, genetically engineered animals have provided unique opportunities to understand the disease process and novel therapeutic strategies for neurodegenerative disorders. Genetically manipulated mice have been and are being used to investigate amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [1,6], Alzheimer's disease [7], motor neuron disease [5,19], Prion diseases [20,24,25], catecholaminergic regulatory systems [3], and Huntington's disease [22,26,27].

We have prepared seven different types of genetically engineered mouse models in our laboratories with the primary objectives of exploring the molecular basis of Parkinson's' disease and understanding and preventing neurodegenerative disorders of aging. All the experimental genotypes used in the study were genotyped by tail DNA-PCR analysis. They included controlwt (C57Bl/6J) mice, metallothionein double gene knockout (MTdko) mice (129S7/SvEvBrd-Mt1 tm1Bri Mt2 tm1Bri/J; JAX, stock no. 002211), metallothionein transgenic (MTtrans) mice (Tg(Mt1)174Bri/J; stock no. 002209), α-synuclein knockout mice (α-Synko) mice, α-synuclein–metallothionein triple knockout mice (α-Syn–MTtko), homozygous weaver mutant mice (wv/wv) (B6CBACaAw-J/A-Kcnj6 wv), and Ames dwarf (p/pProp1 df/J; stock no. 001618) mice. Our studies have shown that metallothionein transgenic (MTtrans) and α-Synko mice are highly suitable to explore basic molecular mechanisms of neuroprotection in PD and aging, whereas MTdko and homozygous weaver mutant (wv/wv) mice can be utilized to understand the basic molecular mechanism of progressive dopaminergic neurodegeneration in PD [16]. Furthermore, Ames dwarf mice can be used to explore specifically the molecular mechanisms of aging and longevity [4]. This review forms a brief report from our laboratories dealing with in vivo and in vitro gene manipulation in order to better understand the basic molecular mechanism(s) of dopaminergic neuro degeneration and to establish the neuro-protective potential of metallothionein isoforms I–III [14,15] in PD and aging.

2. Metallothionein gene-manipulated mice

In view of the above, we have studied the effects of various neurotoxins causing parkinsonism in some of these genotypes. Our studies have indicated that MTtrans mice are genetically resistant to MPTP, 6-OHDA, salsolinol, and rotenone-induced parkinsonism as compared to MTdko mice, which exhibited an enhanced genetic susceptibility to these agents [10]. In order to understand the basic molecular mechanism of genetic susceptibility of MTdko and resistance of MTtrans mice, we exposed these mice to chronic low-dose MPTP. Chronic MPTP (30 mg/kg, i.p., for 7 days) induced severe parkinsonism in MTdko mice, whereas MTtrans mice remained resistant to MPTP-induced parkinsonism. Striatal coenzyme Q10 levels were also significantly reduced in MTdko mice as compared to controlwt, MTtrans, and α-Syn mice. As such, MTdko mice did not exhibit overt clinical symptoms of neurodegeneration as observed in wv/wv mice; however, they were genetically susceptible to MPTP parkinsonism. Chronic treatment with MPTP (30 mg/kg, i.p.) for 7 days induced complete immobilization in MTdko mice, whereas MTtrans mice could still walk with their stiff neck and tail. MTdko mice had significantly reduced skin, body, and SN melanin as compared to MTtrans mice [31,33]. There was no significant difference in the litter size among different experimental genotypes, except α-Syn–MTtko mice (six to eight), which had significantly reduced lifespan. Even cultured fetal stem cells derived from MTtrans mice embryos were resistant to MPP+- and salsolinol-induced apoptosis, and were genetically resistant to bacterial and fungal infection. MTtrans fetal stem cells survived 75±5 days in culture as compared to 55±6 days from the MTdko group (p<0.01) [28].

3. α-Syn–MTtko mice

In order to further explore the basic molecular mechanisms of α-Syn and MTs in the etiopathogenesis of PD, we cross-bred α-Syn males with MTdko female mice and obtained a rare colony of α-Syn–MTtko mice. We examined the effect of chronic rotenone in these genotypes. Our studies have shown that rotenone (1–200 nM) enhanced NFκβ expression and inhibited complex-1 expression in α-Syn–MTtko mice [9,29]. Although the litter size, body size, and lifespans of α-Syn–MTtko mice were significantly reduced as compared to controlwt mice, they provided useful information regarding PD and aging. Indeed, lethargic behavior, reduced body size, and reduced lifespan of α-Syn–MTtko mice were associated with significantly reduced complex-1 activity and mitochondrial coenzyme Q10 levels [31].

4. MTs inhibit salsolinol- and 1-benzyl-tetrahydroisoquinoline induced neurotoxicity

Salsolinol and 1-benzyl-tetrahydroisoquinoline (1-Bn-TIQ) induced α-Syn expression, and apoptosis was suppressed upon MT-1 gene overexpression [28]. MTtrans fetal stem cells were genetically resistant to peroxynitrite ion-generating compound, 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1)-induced dopamine oxidation product dihydroxyl phenyl acetaldehyde (DOPAL), and homovalinic acid (HVA)-induced apoptosis.

We have also discovered MT-3 transcripts in human neuroblastoma (SK-N-SH and SH-SY-5Y) cells. MT-3 overexpression in these cells also significantly suppressed MPP+- and salsolinol-induced apoptosis. Direct exposure of SK-N-SH neurons to MPP+ induced mitochondrial swelling, aggregation, and apoptosis, represented by phosphatidyl serine externalization, plasma membrane blebbing, and perforation, nuclear DNA fragmentation, and condensation [32]. These apoptotic changes were suppressed by selegiline pretreatment, which we have reported to induce brain regional MTs [28]. Taken together, these observations suggest that brain regional induction of MTs (MTI–III) may provide neuroprotection, whereas substances inhibiting mitochondrial complex-1 activity might be injurious and facilitate parkinsonism in experimental animals as well as in humans. MPTP and rotenone induced a significant depletion of striatal mitochondrial coenzyme Q10 in MTdko mice; however, coenzyme Q10 levels remained significantly elevated in MTtrans mice even upon chronic exposure to these parkinsonian neurotoxins [28].

5. MTs attenuate DOPAL apoptosis

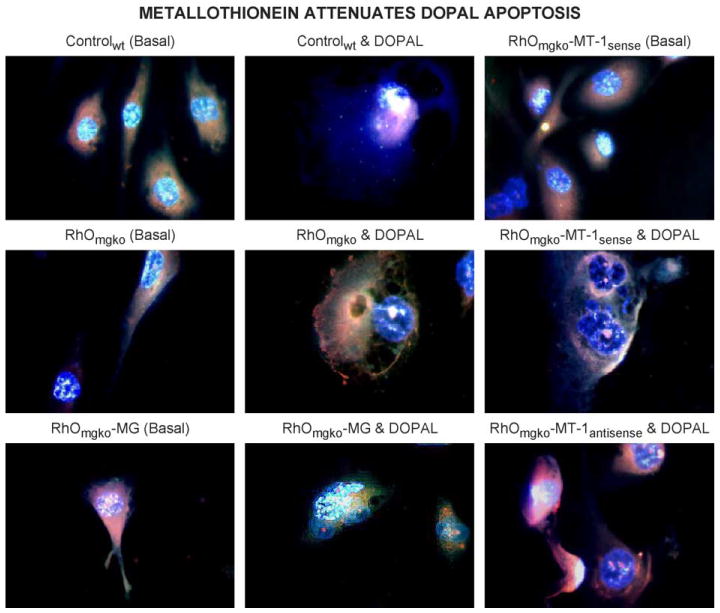

Dopamine oxidation product DOPAL-induced apoptosis in the human dopaminergic (SK-N-SH) cell line was examined in order to validate the observed neuro-protection. Overnight exposure to DOPAL induced apoptosis that was characterized by spherical appearance, plasma membrane perforations, and nuclear DNA condensation as illustrated in Fig. 1. DOPAL-induced apoptosis was also accentuated in aging mitochondrial genome knockout (RhOmgko) neurons. Transfection of RhOmgko neurons with MT-1sense oligonucleotides or with mitochondrial genome encoding complex-1 gene attenuated DOPAL apoptosis, whereas transfection with MT-1antisense oligonucleotides, accentuated DOPAL apoptosis, indicating the neuroprotective role of MTs in oxidative stress of PD.

Fig. 1.

Multiple fluorochrome digital fluorescence microscopic analysis of DOPAL (100 nM)-induced apoptosis in controlwt, aging RhOmgko, RhOmgko-MG, RhOmgko-MT-1sense, and RhOmgko-MT-1antisense oligonucleotide-transfected neurons. DOPAL-induced apoptosis was attenuated in mitochondrial genome and MT-1sense, and augmented in MT-1antisense oligonucleotide-transfected neurons. Fluorescence images were captured by SpotLite digital camera and analyzed by ImagePro computer software (fluorochromes: blue; DAPI; nuclear DNA stain; green: fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), RNA and protein stain; red: ethidium bromide; nuclear DNA stain binds preferentially with fragmented DNA).

6. MTs inhibit MPP+ apoptosis

In order to determine whether MT overexpression provides dopaminergic neuroprotection, we exposed SK-N-SH neurons to MPP+ overnight in culture and performed single cell gel electrophoresis. MT-1sense oligonucloetide-transfected neurons exhibited green comet tails representing mitochondrial damage, whereas MT-1antisense oligonucleotide-transfected neurons exhibited red comet tails representing nuclear DNA damage, indicating that MT down-regulation may induce severe neurodegeneration in dopaminergic neurons [28].

7. SIN-1 enhanced MTs and α-Syn expression

A potent peroxynitrite ion generator, SIN-1, induced MT-1 and α-Syn expression in SK-N-SH neurons in a concentration-dependent manner. SIN-1-induced increases in MT-1 and α-Syn expression were inhibited by either selegiline (10 μM) or coenzyme Q10 (10 μM) pretreatment, suggesting the neuroprotective role of MTs in peroxynitrite-induced oxidative- and nitrative stresses [28].

8. MTs enhance mitochondrial function by augmenting coenzyme Q10 synthesis

Transfection of cultured dopaminergic (SK-N-SH) neurons with antisense oligonucleotides to MT-1 accentuated—whereas transfection with MT-1sense oligonucleotides significantly attenuated—MPP+-, 6-OHDA-, rotenone-, and salsolinol-induced apoptosis [28,30,32]. These data further suggest a neuroprotective role of metallothionein isoforms I–III in PD.

9. MTs stabilize mitochondrial genome

Metallothionein stabilization of the mitochondrial genome was confirmed by preparing a cellular model of aging. The cellular model of aging was prepared by selectively knocking out the mitochondrial genome using 5 μg/l DNA-intercalating agent, ethidium bromide, for 2–3 months in selection medium with appropriate concentrations of glutamine, pyruvate in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), 3.7g/l sodium bicarbonate, and 5% fetal bovine serum. A detailed procedure to prepare and identify RhOmgko neurons is described in a recent publication [30].

Mitochondrial genome knockout neurons are called RhOmgko neurons and have significantly reduced MTs as determined by ELISA [30,42]. Neuritogenesis involved in neuronal growth and development is significantly reduced in RhOmgko neurons, and they exhibit rounded or elliptical appearance with aggregated mitochondria in the perinuclear region. The nuclear genome remains preserved in RhOmgko neurons; however, the concentration of superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione, and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is significantly reduced as compared to wild-type neurons. We characterized these by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis of ND-1 gene encoding mitochondrial complex-1 (ubiquinone-NADH-oxidoreduc-tase). Transfection of RhOmgko neurons with MT1sense enhanced—where as transfection with MT1antisense inhibited—neuritogenesis. Transfection of RhOmgko neurons with mitochondrial genome encoding complex-1 also significantly enhanced neuritogenesis [28]. These observations provide in vitro evidence of the neuroprotective role of MTs through rejuvenation of mitochondrial genome in aging neurons.

10. Homozygous weaver mutant (wv/wv) mice and PD

A single gene point mutation (G156S) in the G-protein-coupled inward-rectifying potassium channel of wv/wv mice [23] induces loss of the external granular layer neurons in the cerebellum [25,37] and dopaminergic cells in the striatum [17,28,40,43]. As a consequence of progressive dopaminergic degeneration, wv/wv mice exhibit instability of gait, poor limb coordination, and resting and intention tremors [39], similar to those observed in PD and chronic drug addiction [12,21]. However, very little is known about how these degenerative changes are triggered in these genotypes. Recently, we have discovered that neurodegeneration in wv/wv mice is associated with inhibition of complex-1 activity and increased levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine, NFκβ [11]. Chronic exposure of rotenone also induced similar changes in α-Syn–MTtko mice and SK-N-SH neurons, suggesting a common molecular mechanism of oxidative stress, induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and induction of apoptotic signaling pathways in neurodegeneration [31].

Recently, we and others have shown that MTtrans and a-Synko mice are genetically resistant to MPTP parkinsonism as compared to wv/wv and MTdko mice [30,43]. As such, MTdko mice did not exhibit overt clinical symptoms of movement disorders; however, they were highly susceptible to MPTP parkinsonism due to significantly reduced striatal coenzyme Q10 as compared to MTtrans and a-Synko mice [28]. Furthermore, we have discovered that endogenously synthesized MPTP-like tetrahydroisoquinolines (TIQs) such as salsolinol and 1-benzyl TIQ-induced α-Syn expression and apoptosis in human dopaminergic (SH-SY5Y) neurons can be attenuated by MT gene over-expression [34,42]. All of these observations encouraged us to propose that since wv/wv mice and MTdko mice are genetically susceptible to MPTP, they could be used to explore neurodegenerative mechanisms, whereas MTtrans mice and α-Synko mice could be used to explore neuro-protective mechanisms in PD. In view of the above, we raised controlwt (C57BL/6J) mice, wv/wv mice, MTdko mice, MTtrans mice, Ames dwarf mice, and α-Synko mice. We have shown that striatal serine phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), 18F-DOPA uptake, complex-1 activity, α-Syn expression, and Mn-SOD is significantly reduced in wv/wv mice as compared to other experimental genotypes. These changes might induce dopaminergic degeneration in wv/wv mice as seen in PD and chronic drug abuse [38].

We have shown that serine phosphorylation of the rate-limiting enzyme, TH, which is involved in dopamine synthesis, is significantly inhibited in wv/wv mice as compared to controlwt, MTdko, MTtrans, and α-Synko mice. Expressing mitochondrial complex-1, Mn-SOD, and α-Syn are also significantly inhibited in wv/wv mice. These data lend support to previous [21,41] and recent observations from our laboratory [13]. Significantly increased mitochondrial Mn-SOD in MTdko mice would indicate a compensatory physiological response to gene manipulation. However, physiological compensation of mitochondrial complex-1 and Mn-SOD was also impaired in wv/wv mice. Thus, wv/wv mice exhibit severe and progressive NS dopaminergic neurodegenerative changes not observed in other experimental genotypes.

11. Neurodegenerative changes in wv/wv mice

By employing digital fluorescence imaging microscopy, we have demonstrated neurodegenerative changes in the striatal and cerebellar regions of wv/wv mice. The neuro-degenerative changes were represented by apoptotic cell death, which was observed primarily in the external granular layer of the cerebellar cortex. Some of the cells from the external granular layer exhibited apoptosis during migration in the internal granular layer, whereas the neurons in the striatal region exhibited aggregated appearance [10,37].

12. 18F-DOPA distribution kinetics and uptake in wv/wv mice

Recently, we have studied in vivo distribution kinetics of 18F-DOPA in wv/wv mice using the high-resolution Concorde microPET imaging system and CTI-RDS-111 cyclotron. We correlated and confirmed microPET findings with conventional neurochemical analysis. The microPET imaging data provided a regression line with a correlation coefficient of 0.89, suggesting that high-resolution microPET imaging can be used to determine the brain regional dopaminergic metabolism in vivo. Micro-PET imaging is highly essential because of the cost of the genetically rare animals. Moreover, microPET imaging is noninvasive and facilitates longitudinal analyses of dopaminergic neurodegeneration in vivo as seen in wv/wv mice. We have now discovered that nigrostriatal 18F-DOPA uptake is significantly reduced in wv/wv mice as compared to controlwt mice. 18F-DOPA was delocalized in the kidneys of wv/wv mice [35]. The observations made from microPET imaging would indicate that chronic l-DOPA therapy in advanced cases of PD may induce nephrotoxicity because of significantly reduced 18F-DOPA uptake in their brain and its delocalization in the kidneys [35]. 18F-DOPA uptake was studied to examine the direct effect of the weaver gene point mutation on DOPA decarboxylase activity. Significantly reduced 18F-DOPA uptake would indicate reduced DOPA decarboxylase in wv/wv mice. In a previous study, we have shown that dopamine synthesis is significantly reduced in wv/wv mice. MPTP-induced striatal release was significantly high in MTtrans mice as compared to wv/wv, MTdko, and α-Synko mice. Interestingly, striatal release of the dopamine oxidation product DOPAL and HVA was also significantly (p<0.01) increased in wv/wv mice. These neurochemical changes are reflected as progressive neurobehavioral abnormalities in wv/wv mice [13].

13. Abnormal function of α -Syn in wv/wv mice

We have also demonstrated that SDS-soluble α-Syn is significantly reduced in wv/wv mice, which renders them highly susceptible to dopaminergic neurodegeneration and hence parkinsonism. By using digital immunofluorescence imaging, we discovered α-Syn aggregates in the degenerating striatal dopaminergic neurons of wv/wv mice [13]. However, the basic molecular mechanisms of α-Syn aggregation and progressive loss of dopaminergic neuro-transmission in wv/wv remain enigmatic. It seems that SDS-soluble α-Syn might have some unknown regulatory role in dopaminergic neurotransmission, whereas SDS-insoluble and aggregated α-Syn might be responsible for neuro-degeneration, which remains to be established.

In a recent study, we have reported that the distribution kinetic of 18F-DOPA is impaired in wv/wv mice by using high-resolution microPET imaging [32]. 18F-DOPA uptake was significantly reduced in the central nervous system (CNS) and was relocalized in the kidneys of wv/wv mice. These observations further confirmed impaired CNS dopaminergic neurotransmission in wv/wv mice. Dopaminergic neurons and their projection systems are important in some fundamental human activities like locomotion, feeding, and reproduction; essential for survival and procreation; and are relevant to pathologies like PD and drug addiction [13]. Mutant animals with defects specific to one or more projection systems might be useful for studying the role of individual dopaminergic projection systems [21]. Since wv/wv mice exhibit age-dependent nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurodegeneration as observed in PD even without any exogenous neurotoxic insult, they may be used to explore the basic molecular mechanism of progressive neurodegeneration in PD.

Although MT gene ablation renders MTdko mice highly susceptible to PD, progressive neurodegeneration as observed in wv/wv mice was not observed in these animals [31]. However, significantly reduced serine(40)-phosphorylated TH immunoreactivity particularly in the wv/wv mice striatum suggests that the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system is highly susceptible to the weaver gene point mutation as compared to other gene manipulations. For example, Mn-SOD expression was significantly increased in MTdko mice but remained unchanged in MTtrans and α-Synko mice, indicating the neuroprotective role of MTs. Significantly reduced Mn-SOD expression would suggest impaired mitochondrial bioenergetics in wv/wv mice, and significantly high Mn-SOD in MTdko mice would suggest physiological compensation in response to MT gene ablation. Furthermore, reduced complex-1 expression would also indicate impaired mitochondria bioenergetics in wv/wv and MTdko mice. Previous studies have also reported mitochondrial damage during CNS development in wv/wv mice [43]. We have shown that MPP+-induced DNA fragmentation was exaggerated in aging RhOmgko, MTdko, and caspase-3-transfected dopaminergic (SK-N-SH) neurons, and was significantly reduced in MT-overexpressing neurons [28]. MPP+-induced degenerative changes were attenuated in MTtrans, MT-1, and mitochondrial genome-transfected neurons, indicating the neuroprotective role of MTs [29].

It has been reported that the density of striatal dopaminergic nerve terminals was increased following riluzole administration in wv/wv mice, suggesting its protective role in dopaminergic neurons [9]. Transplantation of E12 mesencephalic cells into the striatal region of DA-deficient wv/wv mice improved glutamatergic corticostriatal and dopaminergic nigrostriatal pathways as estimated by 3H-CNQX and 3H-glutamate binding studies [21]. Dopamine D2 receptor-like immunoreactivity was significantly reduced in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) of wv/wv mice and the synaptic number was also reduced. Degenerative changes were observed in some of the D2 receptor-like immunoreactive profiles, suggesting that the synaptic integrity of the dopaminergic system in the striatum is compromised in wv/wv mice, which in turn affects the functional efficacy of the basal ganglia circuitry. Thus, the altered nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurocircuitry is expressed as Parkinson-like symptoms in these genotypes [41]. In addition to significantly reduced TH, α-Syn, 18F-DOPA uptake, and complex-1, wv/wv mice exhibit significantly reduced dopamine, ATP, coenzyme Q10, and progressive neurodegeneration in the hippocampal dentate gyrus and cerebellar cortex [13]. These multiple neurodegenerative changes occur concomitantly with neurobehavioral abnormalities, morbidity, and eventually mortality in wv/wv mice [13].

14. MTtrans striatal fetal stem cell transplantation

In an in vitro analysis, we confirmed that MTtrans striatal fetal stem cells are genetically resistant to the dopamine oxidation product DOPAL and to 1-methyl-4-phenyl pyridinium ion (MPP+)-induced apoptosis [30]. Since MTtrans striatal fetal stem cells are genetically resistant to environmental and parkinsonian neurotoxins, and wv/wv mice exhibit progressive dopaminergic neurodegeneration in the NS system during aging, we have now proposed to explore the structural and functional integrity of MTtrans and Ames dwarf mouse fetal stem cells grafts in wv/wv mice by employing 18F-DOPA and 18F-rotenone microPET neuro-imaging. These studies will provide more precise information regarding the success rate of fetal stem cell transplantation and other unexplored yet important issues on graft rejection and acceptance in PD.

We have shown that α-Synko mice were highly resistant, whereas MTdko mice and weaver mutant mice were highly susceptible to chronic MPTP and rotenone-induced α-Syn nitration, complex-1 inhibition, and NFκβ activation [11]. MTdko mice did not exhibit obvious clinical symptoms of neurodegeneration; however, mitochondrial Mn-SOD was significantly induced in these genotypes as a physiological adaptation to MT gene ablation. Progressive and severe NS dopaminergic neurodegenerations associated with typical parkinsonism (neck muscle rigidity, body tremors, walking difficulties, and postural irregularities) were observed in adult wv/wv mice. Furthermore, wv/wv mice exhibited significant reduction in serine phosphorylation of TH, reduced 18F-DOPA uptake, and α-Syn expression [13].

15. Neuroprotective role of TRPC1 in PD

Mammalian homologues of the Drosophila canonical transient receptor potential (TRP) protein have been implicated to function as Ca2+ channels [36]. In a recent study, we have explored the molecular mechanism of neuroprotection by TRPC1 in human dopaminergic (SH-SY-5Y) cells. TRPC1 expression was significantly inhibited by exposing the human dopaminergic (SH-SY-5Y) cells to MPP+ or salsolinol. Overexpression of TRPC1 in SH-SY-5Y neurons provided protection against these parkinsonian neurotoxins and inhibited the translocation of protein needed for apoptosis as confirmed by immunoblotting and confocal microscopy [44].

16. Increased lifespan of Ames dwarf mice

We have discovered that Ames dwarf mice survived 2.5 longer than controlwt mice [4]. Studies conducted on long-living Ames mice have shown that these mice express higher levels of metallothionein isoforms and antioxidant enzymes, produce fewer free radicals, and exhibit less DNA and protein oxidative damage when compared to age-matched wild-type mice [45–48]. In addition, dwarf mice outsurvive controlwt mice when challenged in vivo with the systemic oxidative stressor, paraquat. Importantly, we have shown that metallothionein levels are significantly higher in dwarf tissues compared to wild-type tissues [4]. These observations, along with those in lower species, indicate that reduced growth hormone signaling enhances antioxidant expression and extends lifespan.

17. Conclusions

Pharmacological interventions involving brain regional induction of MTs, TRPC1, and regulating growth hormone expression might be helpful in the clinical management of PD and other neurodegenerative disorders of unknown etiopathogenesis. Brain regional induction of MTs, in addition to metal detoxification, helps in reactive oxygen species scavenging, coenzyme Q10 synthesis, complex-1 activation, attenuation of α-Syn nitration, and suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα and NFκβ involved in the etiopathogenesis of PD and aging. These data indicate that brain regional induction of MTs might be helpful in the prevention of PD in aging brain; whereas MTtrans mice and Ames dwarf mice could be further explored to understand the success rate of fetal stem cell transplantation in PD and other diseases such as AD. Based on the present study, it is suggested that wv/wv mice and MTdko mice could be used to investigate the basic molecular mechanism of neurodegeneration, whereas MTtrans mice, Ames dwarf mice, and α-Synko mice could be used to explore the basic molecular mechanism of neuroprotection in PD and movement disorders and neurological impairments associated with chronic cocaine, MPTP, or amphetamine addiction. Further studies in this direction are in progress. Furthermore, Ames dwarf mouse model would provide more leads in the basic understanding of aging, oxidative stress, and longevity.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Counter Drug Technology Assessment Center, Office of National Drug Control Policy (no. DATMO5-02C-1252, to M.E.), a grant from NINDS (no. 2R01 NS3456609, to M.E.), and grant R01 AG17059-09 (to M.E.). The excellent secretarial skills of Mrs. Dani Stramer in preparing this manuscript are gratefully acknowledged.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- DA

dopamine

- DA-ergic neurons

dopaminergic neurons

- 18F-DOPA

6-18fluoro-l-dihydroxy phenylalanine

- GIRK channel

G-protein-activated inward-rectifying K+ channel

- wv/+

heterozygous weaver mutant mice

- wv/wv

homozygous weaver mutant mice

- MTdko mice

metallothionein double gene knockout mice

- MTtrans mice

metallothionein transgenic mice

- PD

Parkinson's disease

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- SNpc

substantia nigra pars compacta

- α-Syn

α-synuclein

- α-Synko mice

α-synuclein knockout mice

- α-Synko–MTtko mice

α-synuclein–metallothionein triple knockout mice

- TH

tyrosine hydroxylase

References

- 1.Aguzzi A, Brandner S, Marino S, Steinbach J. Transgenic and knockout mice in the study of neurodegenerative diseases. J Mol Med. 1996;74:111–126. doi: 10.1007/BF01575443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betarbet R, Sherer BT, Greenamyre TJ. Animal models of Parkinson's disease. BioEssays. 2002;24:308–318. doi: 10.1002/bies.10067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Björklund A, Lindvall O. Catecholaminergic Brain Stem Regulatory Systems. Waverly Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown-Borg HM, Borg KE, Meliska CJ, Bartke A. Dwarf mice and the ageing process. Nature. 1996;384:33. doi: 10.1038/384033a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruijn L, Cleveland D. Mechanisms of selective motor neuron death in ALS: insights from transgenic mouse models of motor neuron disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1996;22:373–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1996.tb00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crowther R. Steps towards a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. BioEssays. 1995;17:593–595. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daurer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson's disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:88–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Douhou A, Debier T, Murer MG, Do L, Dufour N, Blanchard V, Moussaoui S, Bohme GA, Agid Y, Raisman-Vozari R. Effect of chronic treatment with riluzole on the NS DA-ergic system in wv/wv mice. Exp Neurol. 2002;176:247–253. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.7935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ebadi M, Sharma S. Complex-1 is inhibited and NFκβ is induced in weaver mutant mice. J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:213–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ebadi M, Sharma S. Peroxynitrite and mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5:319–335. doi: 10.1089/152308603322110896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ebadi M, Sharma S, Muralikrishnan D, Shavali S, Eken J, Sangchot P, Chetsawang B, Brekke L. Metallothionein provide ubiquinone-mediated neuroprotection in Parkinson's disease. Proc West Pharmacol. 2002;45:36–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebadi M, Sharma SK, Ajimaporn A, Maanum S. Weaver mutant mouse in progression of neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. In: Ebadi M, Pfeiffer RF, editors. Parkinson's Disease. CRC Press; Florida: 2005. pp. 541–559. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebadi M, Sharma S, Ghafourifar P, Brown-Barg H, El Rafaey H. Peroxynitrite in the pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease and the neuroprotective role of metallothioneins. Methods Enzymol. 2005 doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)96024-2. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El Refaey H, Ebadi M, Kuszynski CA, Sweeney J, Hamada FM, Hamed A. Identification of metallothionein receptors in astrocytes. Neurosci Lett. 1997;231:131–134. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00548-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrett SH, Belcastro M, Sens MA, Somji S, Sens DA. Acute exposure of arsenite induces metallothionein isoform-specific gene expression in human proximal tubule cells. J Toxicol Environ Health, A. 2001;26(64 (4)):343–355. doi: 10.1080/152873901316981321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gupta M, Petten DL, Ghetti B. Selective loss of monoaminergic neurons in weaver mutant mice—an immunocytochemical study. Brain Res. 1987;402:379–382. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitamura Y, Shimohama S, Akaike A, Taniguchi T. The parkinsonian models: invertebrates to mammals. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2000;84:237–243. doi: 10.1254/jjp.84.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee M, Borchelt D, Wong P, Sisodia S, Price D. Transgenic models of neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1996;6:651–660. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(96)80099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludolph A. Animal models for motor neuron diseases: research directions. Neurology. 1996;47:S228–S232. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.6_suppl_4.228s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maharajan P, Maharajan V, Ravagnan G, Paino G. The weaver mutant mouse: a model to study the ontogeny of dopamine transmission systems and their role in drug addiction. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;64:269–276. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menalled LB, Chesselet MF. Mouse models of Huntington's disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2002;23:32–39. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01884-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitsacos A, Tomiyama M, Stasi K, Giompres P, Kouvelas ED, Cortes R, Palacois JM, Mengod G, Triarhou LC. [3H]CNQX and NMDA-sensitive [3H]glutamate binding sites and AMPA receptor subunit RNA transcripts in the striatum of normal and wv/wv mice and affects of ventral mesencephalic grafts. Cell Transplant. 1999;8:11–23. doi: 10.1177/096368979900800111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patil N, Cox DR, Bhat D, Faham M, Myers RM, Peterson AS. A potassium channel mutation in weaver mice implicates membrane excitability in granule cell differentiation. Nat Genet. 1995;11:126–129. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prusiner S. Prion diseases and the BSE crisis. Science. 1997;278:245–251. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5336.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rakic P, Sidman L. Sequence of developmental abnormalities leading to granule cell deficit in cerebellar cortex of weaver mutant mice. J Comp Neurol. 1973;152:103–132. doi: 10.1002/cne.901520202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubinstein DC. Lessons from animal models of Huntington's disease. Trends Genet. 2002;18:202–209. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02625-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schmidt MJ, Sawyer BD, Perry KW, Foreman MM, Ghetti B. Dopamine deficiency in the weaver mutant mouse. J Neurosci. 1982;2:376–380. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-03-00376.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma S, Ebadi M. Metallothionein attenuates 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1)-induced oxidative stress in DA-ergic neurons. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2003;5:251–264. doi: 10.1089/152308603322110832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma S, Ebadi M. An improved method for analyzing coenzyme Q homologues and multiple detection of rare biological samples. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;137:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma SK, Carlson EC, Ebadi M. Neuroprotective actions of selegiline in inhibiting 1-methyl, 4-phenyl, pyridinium ion (MPP+)-induced apoptosis in SK-N-SH neurons. J Neurocytol. 2003;32:329–343. doi: 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000011327.23739.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma S, Kheradpezhouh M, Shavali S, El Refaey H, Eken J, Hagen C, Ebadi M. Neuroprotective actions of coenzyme Q10 in Parkinson's disease. Methods Enzymol. 2004;382:488–509. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)82027-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma SK, Keawphalouk M, Ajiimaporn A, Ebadi M. Distribution kinetics of 18F-DOPA in weaver mutant mice. J Neurochem. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2005.05.018. submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ebadi M, Sharma S, Wanpen S, Shavali S. Metallothionein isoforms attenuate peroxunitrite-induced oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease. In: Ebadi M, Pfeiffer RF, editors. Parkinson's Disease. CRC Press; Florida: pp. 483–503. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shavali S, Carlson EC, Swinscoe JC, Ebadi M. 1-Benzyl-1, 2,3,6-tetrahydroisoquinoline, a Parkinsonism-inducing endogenous toxin increases alpha-synuclein expression and causes nuclear damage in human dopaminergic cells. J Neurosci Res. 2004;76:563–571. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sidman RL, Green MC, Appel SH. Catalog of the Neurological Mutants of the Mouse. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1965. pp. 66–67. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh BB, Liu X, Tang J, Zhu MX, Ambudkar IS. Calmodulin regulates Ca2+-dependent feedback inhibition of store-operated Ca2+ influx by interaction with a site in the C terminus of TrpC1. Mol Cell. 2002;9:739–750. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00506-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smeyne RJ, Goldowitz D. Development and death of external granular layer cells in the weaver mouse cerebellum: a quantitative study. J Neurosci. 1989;9:1608–1620. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-05-01608.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith MW, III, Cooper TR, Joh TH, Smith DE. Cell loss and class distribution of TH-I cells in the substantia nigra of the neurological mutant, weaver. Brain Res. 1990;510:242–250. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91374-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tinmarlar FO, Richard BJ, Harrison MWS, Henchcliffe C, Mason CA, Roffler-Tarlov SK, Burke RE. Neuron death in substantia nigra of weaver mouse occurs late in development and is not apoptotic. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6134–6145. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06134.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Triarhou LC. Biology and pathology of weaver mutant mouse. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;517:15–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0699-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Triarhou LC, Norton J, Ghetti B. Mesencephalic dopamine cell deficit involves areas A8, A9 and A10 in weaver mutant mice. Exp Brain Res. 1988;70:256–265. doi: 10.1007/BF00248351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wanpen S, Govitrapong P, Shavali S, Sangchot P, Ebadi M. Salsolinol, a dopamine-derived tetrahydroisoquinoline, induces cell death by causing oxidative stress in dopaminergic SH-SY-5Y cells, and the said effect is attenuated by metallothionein. Brain Res. 2004;1005:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu SG, Prasad C, Smith DE. Neurons exhibiting DA D2 receptor immunoreactivity in the substantia nigra of the mutant weaver mouse. Neuroscience. 1999;89:191–207. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bollimuntha S, Singh BB, Shavali S, Sharma SK, Ebadi M. TRPC1-mediated inhibition of MPP+ or salsolinol neurotoxicity in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastems cells. J Biol Chem. 2004 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407384200. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown-Borg HM. Hormonal regulation of aging and life span. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14:151–153. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(03)00051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown-Borg HM, Johnson WT, Rakoczy SG, Romanick MA. Mitochondrial oxidantproduction and oxidative damage in Ames dwarf mice. J Am Aging Assoc. 2001;24:85–96. doi: 10.1007/s11357-001-0012-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown-Borg HM, Rakoczy SG. Catalase expression in delayed and premature aging mouse models. Exp Gerontol. 2000;35:199–212. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(00)00079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bartke A, Brown-Borg HM, Kinney B, Mattison J, Wright C, Hauck S, Coschigano K, Kopchick J. Growth hormone and aging. J Am Aging Assoc. 2000;23:219–225. doi: 10.1007/s11357-000-0021-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]