Abstract

The Early Cambrian organism Olivooides is known from both embryonic and post-embryonic stages and, consequently, it has the potential to yield vital insights into developmental evolution at the time that animal body plans were established. However, this potential can only be realized if the phylogenetic relationships of Olivooides can be constrained. The affinities of Olivooides have proved controversial because of the lack of knowledge of the internal anatomy and the limited range of developmental stages known. Here, we describe rare embryonic specimens in which internal anatomical features are preserved. We also present a fuller sequence of fossilized developmental stages of Olivooides, including associated specimens that we interpret as budding ephyrae (juvenile medusae), all of which display a clear pentaradial symmetry. Within the framework of a cnidarian interpretation, the new data serve to pinpoint the phylogenetic position of Olivooides to the scyphozoan stem group. Hypotheses about scalidophoran or echinoderm affinities of Olivooides can be rejected.

Keywords: Olivooides, cnidarian, scyphozoan, medusa, fossil, embryo

1. Introduction

The discovery of fossilized embryos of marine invertebrates in rocks laid down contemporaneously with the emergence of animal phyla has opened a new vista on embryological evolution [1–3]. However, the potential significance of these fossils can only be realized if their phylogenetic affinity can be constrained, and if significant episodes of their embryology are preserved [4]. Olivooides is exceptional in the extent to which its development is represented by fossils, including stages interpreted as both embryonic and post-embryonic development [1,5]. Its apparent direct mode of development without an intervening larval stage has been marshalled as evidence against the hypothesis that the animal phyla inherited a plesiomorphic indirect mode of development [1,4,6]. However, the phylogenetic affinities of Olivooides remain controversial because its anatomy has been inferred exclusively through its all-enveloping integument. Its single pentameral orifice has led to diverse interpretations of phylogenetic affinity with cnidarians [1,5], scalidophorans [7] and echinoderms [8]. We attempted to constrain the phylogenetic interpretations using evidence from new developmental stages and microtomographic analysis of the fossils, revealing preserved anatomy inside the more commonly preserved integument.

2. Material and methods

Our material is from the Early Cambrian Kuanchuanpu Formation at the Shizhonggou section near Kuanchuanpu village, Ningqiang County, Shaanxi Province, China. Fossils were recovered by digestion of limestone in ca 10 per cent acetic acid and were then separated from the insoluble residue by manual picking under a binocular microscope. Specimens were analysed using environmental scanning electron microscopy, conventional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and synchrotron radiation X-ray tomographic microscopy (SRXTM; [9]). SRXTM analyses were carried out at the X04SA Materials Science [10] and X02DA TOMCAT [11] beamlines of the Swiss Light Source, Paul Scherrer Institute, Villigen, Switzerland. All figured material is reposited in the collections of the Geological Museum of Peking University, Beijing (GMPKU).

3. Results

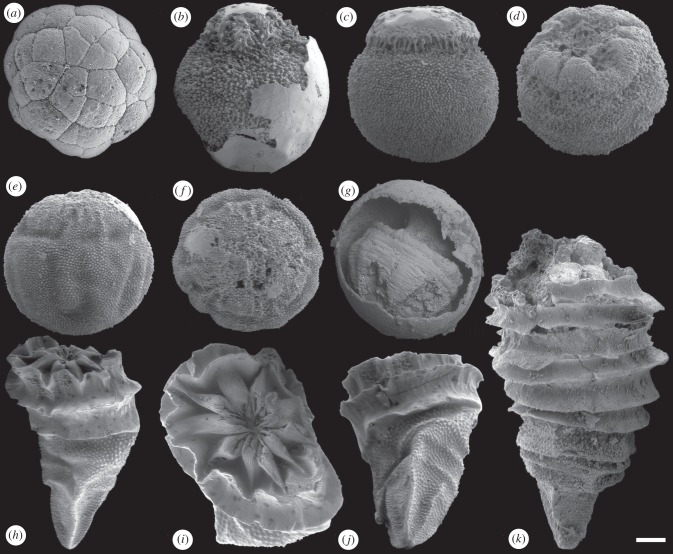

The earliest known developmental stages of Olivooides are cleavage embryos ([1,5]; figure 1a). Later developmental stages are spheroidal with a stellate integument and pentaradial aperture, enclosed within what has been interpreted as a fertilization envelope (figure 1b–f). On hatching, the aperture expanded, transforming the spheroid into a conical structure, the ‘Punctatus’ stage (figure 1h–k), which increased in height through development, with growth at the aperture that appears to have been capable of opening and closure. The evidence of association between the later developmental stages rests with the presence of a characteristic stellate and ribbed integument as well as pentaradial symmetry in both the putative embryonic and the post-embryonic stages; the attribution of associated cleavage stages to Olivooides is currently based solely on co-association [5,12].

Figure 1.

Embryos and polyps of Olivooides. (a) Cleavage-stage embryo (GMPKU3080). (b) Stellate embryo with raised apertural rays (GMPKU3081). (c) Stellate embryo with a raised apertural region (GMPKU3082). (d) Stellate embryo with an infolded apertural region (GMPKU3084). (e–f) Stellate embryo showing a characteristic pattern of bulges in (e) lateral, and (f) apertural aspect (GMPKU3083). (g) Embryo within fertilization envelope that preserves the characteristic pattern of bulges, but not the stellate tissue (GMPKU3085). (h–j) Early post-embryonic polyp stage exhibiting characteristic stellate integument of embryonic stage, but exhibiting the annulated striated adapertural tissue, and the pentamerally enfolded aperture, in (h) lateral, (i) apertural and (j) oblique aspects (GMPKU2317). (k) Later polyp-stage specimen in lateral aspect (GMPKU3086). Scale bars: (a) 69 µm, (b) 116 µm, (c) 139 µm, (d) 125 µm, (e,f) 132 µm, (g) 164 µm, (h) 275 µm, (i) 118 µm, (j) 250 µm, (k) 262 µm.

SRXTM of numerous specimens has shown that, cleavage embryos aside, internal preservation of Olivooides embryos is exceedingly rare [13]. Only the stellate integument and fertilization envelope are usually preserved; the bulk of the fossil is usually a homogeneous calcium phosphate mineral endocast of the integument, sometimes exhibiting voids spanned by filaments resembling fungal hyphae [5]. We have identified only three specimens that yield direct information on the internal anatomy of the late embryonic stages of Olivooides (figures 2 and 3). The anatomical structures are distinguished because of differences in the X-ray attenuation of mineral phases that replicate the biological structures versus later void-filling diagenetic mineralization. The features are interpreted to reflect original anatomical structure because they exhibit complexities that cannot be explained by mineralization that is random or templated on the preserved integument. Furthermore, they exhibit the same radial symmetry manifest in the aperture of the integument.

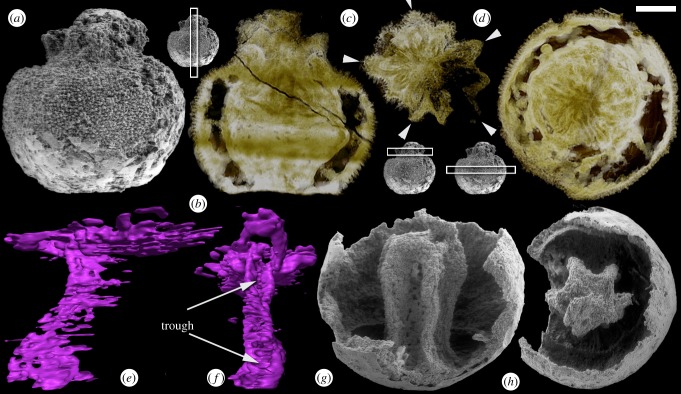

Figure 2.

Embryonic Olivooides specimens with internal preservation. (a–f) Specimen with five-rayed internal structures (GMPKU3087). (a) SEM image of whole specimen in lateral view. (b–d) SRXTM-based virtual thin sections with insets showing the positions of the sections within the specimen. (b) Longitudial section showing biological preservation in the upper third. (c) Transverse section showing apertural rays, arrows indicate primary rays which are intercalated by interrays. (d) Transverse section showing the rays at depth. (e,f) SRXTM renderings of a single ray in lateral (e) and adaxial (f) aspects; arrows indicate the trough formed at depth within the ray. (g,h) Specimen preserving a pentagonal axial mould (GMPKU3088) imaged using SEM. (g) Lateral view. (h) Apertural view. Scale bars: (a,b,d) 155 µm, (c) 132 µm, (e,f) 46 µm, (g) 150 µm, (h) 170 µm. (Online version in colour.)

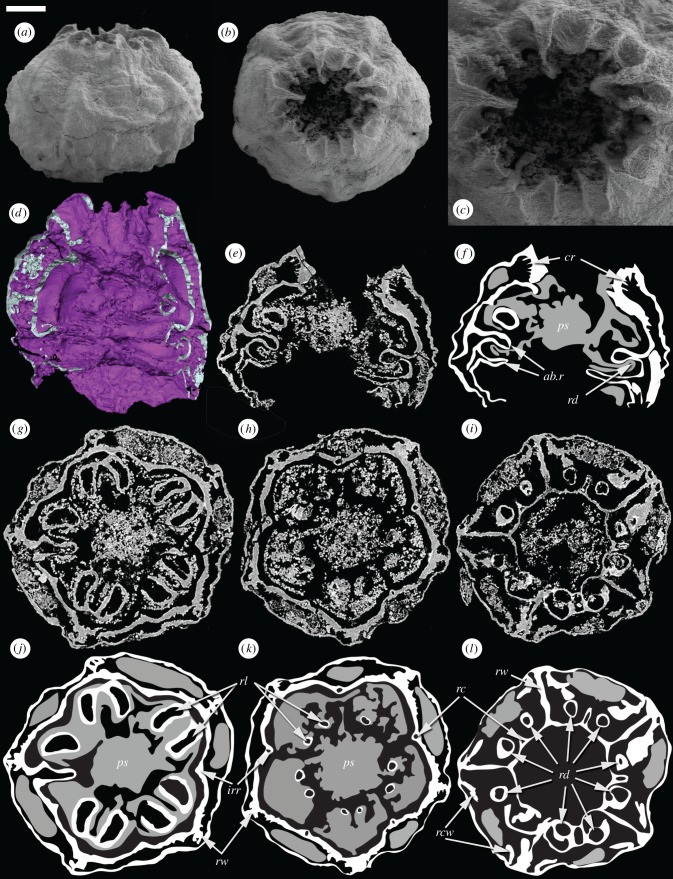

Figure 3.

Embryonic Olivooides specimen with internal preservation (GMPKU3089) imaged using SEM (a–c) and SRXTM (d–l). (a) Whole specimen in lateral view. (b) Whole specimen in apertural view. (c) Detail of the aperture. (d) Surface rendering showing the internal anatomy. (e,f) Longitudinal section and interpretative drawing. (g,j) Transverse section and interpretative drawing showing paired projections from the inner wall and radial structures that connect the inner and outer walls. (h,k) Transverse section and interpretative drawing in particular showing interadial canals. (i,l) Transverse section and interpretative drawing showing the inner wall extending into the lumen to form the upper abradial ridge; depressions in the lower surface of the ridge appear as paired circular structures in section. Within the interpretative drawings, white represent a dense highly X-ray attenuating mineral phase, while grey reflects a more diffuse lowly attenuating mineral phase; both are interpreted to reflect original biological structure. ab.r, abradial ridges; cr, circumferential ridges; irr, interradial ridge; ps, polygonal axial structure; rc, radial canal; rcw, recurved wall; rd, radial depression; rl, radial lobe; rw, radial wall. Scale bars: (a,b) 153 µm, (c) 73 µm, (d) 78 µm, (e,f) 124 µm, (g,j) 119 µm, (h,k) 136 µm, (i,l) 143 µm. (Online version in colour.)

The first of these fossilized remains (figure 2a–f) represents an embryo in the earliest stages of morphogenesis that we have identified, with raised apertural rays and an entirely stellate integument (figure 2a–d). The specimen remains partially covered in an envelope (figure 2a). SRXTM analysis shows that the interior of the specimen forms a central mass that is separated from the outer stellate wall (figure 2b,d), except for the infolded upper region (figure 2c). The interior of the stellate wall, as well as the outside of the central mass, has been thickened by diagenetic mineral growth, leaving an intermediate space with some mineralized filaments (figure 2b,d). The extent of preserved biological structure is limited to the one third of the embryo closest to the orifice; the remainder is composed of later void-filling diagenetic mineralization after decay of the tissues (figure 2b). The orifice of the specimen is organized into five principal and five intercalary raised apertural rays that exhibit pentameral organization (figure 2b,c). The rays have a hollow central region (now infilled with a higher X-ray attenuating mineral phase; figure 2c) and the fold of tissue bifurcates with depth (figure 2b,d–f), producing a groove that opens to the radial pole (figure 2e,f). At depth, the five principal rays of the structure merge (figure 2b,e,f). An incompletely preserved specimen better conveys the lower portions of this polygonal axial structure (figure 2g,h), which appears to represent a directly preserved equivalent of pentagonal axial moulds that are more commonly preserved. If nothing else, these structures demonstrate that the pentameral symmetry of the lobes surrounding the orifice is fundamental to the organization of the internal anatomy. It is unclear whether these structures relate to the development of the integument or whether they represent aspects of the intrinsic internal anatomy of the organism.

A third specimen (figure 3) lacks the diagnostic stellate integument of Olivooides embryos but nevertheless preserves a number of features which indicate that it is an embryo of Olivooides in which the integument has been lost taphonomically, preserving only features of internal anatomy. This specimen exhibits a different preservation to the first, with two mineral phases preserving different aspects of anatomy; there appears to be no void-filling mineral phase. These mineral phases differ in their density and X-ray attenuation (figure 3e–l). A dense, highly attenuating phase preserves unequivocal anatomical structure. A more diffuse lower-attenuating phase exhibits a consistency of distribution reflecting the pentradial structure of the first, a feature that is difficult to explain away as void-filling mineralization. The terminal orifice preserves pentaradially arranged principal rays with paired subordinate intercalary rays (figure 3b–d). The principal rays are continuous with broad ridges that are parallel to the axis of radial symmetry in the embryo (figure 3a,b; cf. figure 1e, f), and the paired subordinate rays are aligned but discontinuous with five further radially aligned bulges (figure 3a,b; cf. figure 1e,f). These broad ridges compare with the expressions of internal anatomy on the stellate integument of other specimens that do not otherwise preserve internal anatomy (figure 1e,f). The adapertural surface of the embryo is incompletely preserved.

SRXTM analysis revealed that the specimen has an inner and an outer wall (figure 3d–l). Between the two walls, a series of concentric ridges run around the circular opening (cr, figure 3e,f); these have higher X-ray attenuation than the remainder of the specimen. In the portion below the oral constriction, five radial walls (rw) connect the inner and outer walls (figure 3g–l). In the lower portion of the specimen, short recurved walls (rcw) extend bilaterally from the principal radial walls into the cavity between the inner and outer walls (figure 3g–l). The inner wall has prominent ridges (irr) that correspond to the interradial exterior ridges (figure 3a; cf. figure 1e, f). The ridges on the inner wall contain radial canals (rc; figure 3h,i,k,l) that follow the folds in the wall; close to the opening they are incompletely preserved. The outer wall exhibits similar canals, but these are less well preserved and only two are visible in the virtual sections. Below the aperture, the inner wall extends into 10 lobes (rl) that occur in five pairs arranged about the principal radial walls (figure 3g,j). In the aboral region, the inner wall twice extends approximately one third of the distance into the central lumen creating two circumferential abradial ridges (ab.r; figure 3d–f,i,l). In the upper of these there are 10 depressions in the lower surface (rd), which lie in pairs beneath the 10 lobes (figure 3i). These structures are independent from the central polygonal shaft (figure 2g,h) that appears to be present but less well preserved in a diffuse mineral phase in this specimen (ps; figure 3g,h,j,k). The radial lobes (rl) appear to be distinct internal structures with the same pentaradial organization seen in other aspects of embryonic and post-embryonic anatomy. The external topography of the inner wall mirrors the bulges seen in the stellate ornament of embryos in figure 1e,f.

A unique star-shaped specimen (figure 4a–c) shows features that suggest it to represent part of the life cycle of Olivooides. The specimen has 10 rays, arranged in two whorls of five rays each. The two whorls are tightly adpressed to each other, but they can be distinguished by the manner in which the rays alternatively underlie or overlie adjacent arms (figure 4b). One side of the specimen has a central depression (figure 4c) that we interpret tentatively as a mouth, making this the oral side. We ally this developmental stage with Olivooides because it shows the same unusual symmetry.

Figure 4.

Two adpressed ephyra-stage Olivooides specimens (GMPKU3090). (a) SEM image showing the whole specimen in aboral view. (b) SEM image showing a detail of the aboral surface; note the alternately overlying and underlying arms. (c) SRXTM surface rendering showing a detail of the adoral surface including the presumed mouth. Scale bars: (a) 49 µm, (b) 27 µm, (c) 28 µm. (Online version in colour.)

4. The phylogenetic affinity of Olivooides

We resisted identifying anatomical homologies in our description of the fossil remains, because in doing so we would have prejudged the phylogenetic affinity of Olivooides. Below we consider our results in light of the three proposed hypotheses of affinity for Olivooides, as a priapulid [7], an echinoderm [8] and as a cnidarian [1,5].

(a). Priapulid affinity

One group with which Olivooides has drawn comparisons is the priapulid worms and in particular the loricate larvae of this group [1,5]. These comparisons are based on the overall resemblance of the embryonic stages of Olivooides and priapulids. First, pentaradial symmetry is exhibited both in Olivooides and in the mouthparts and pharynx of priapulids [14]; this is a feature that is extremely rare outside of the echinoderms. Second, the stellae of Olivooides have been compared with the sensory scalids of priapulids as well as sensory structures in other taxa [5]. Comparison could also be drawn between the lorica of larval priapulids and the conical stellate–striate sheath that the embryonic and post-embryonic stages of Olivooides share. However, despite these similarities, there are convincing arguments against a priapulid affinity for Olivooides. The apex of Olivooides is not perforated and the animal has a single orifice that must have served for both mouth and anus. This is incompatible with a priapulid interpretation, as both larval and adult priapulids have a through gut with a distinct mouth and anus at opposing poles of the primary body axis. Direct continuous development from the embryo through to the post-embryonic ‘Punctatus’ stage also provides evidence against a priapulid affinity. With the exception of Meiopriapulus [15] which lacks a lorica altogether, extant priapulids have multi-plated loricate larvae that metamorphose into a juvenile worm [14,16], as opposed the continuous stellate sheath of embryonic Olivooides. In conclusion, the comparison of Olivooides to scalidophorans is vague and superficial and we reject a scalidophoran hypothesis of affinity.

(b). Echinoderm affinity

Chen [8] argued for an echinoderm affinity for Olivooides on the basis of its pentaradial symmetry and because symmetry is widely held to be a character that is both very important and highly conserved during early animal evolution [17]. We reject the hypothesis of echinoderm affinity on several grounds. First, pentaradial symmetry is not unique to the echinoderms and is known from other phyla including priapulids and cnidarians. Second, no other aspect of Olivooides anatomy suggests a relationship with echinoderms and it lacks many important echinoderm characters. Most conspicuously, Olivooides lacks: (i) a calcitic skeleton formed of discrete plates with a mesh-like stereom structure, (ii) a water vascular system with tube feet arranged along branches (ambulacra), and (iii) a through gut. All of these character complexes were gained in stem-echinoderms prior to the evolution of pentameral symmetry [18]. They would all have to have been lost in order to accommodate Olivooides within the echinoderms, an hypothesis of affinity that rests merely on a common pattern of symmetry. In sum, we reject an echinoderm hypothesis of affinity for Olivooides.

(c). Cnidarian affinity

The principal hypothesis of phylogenetic affinity for Olivooides is with Cnidaria and, more specifically, with the coronate scyphozoans [1,5]. Within this framework of interpretation, the post-embryonic conical stages of Olivooides are interpreted as peridermal sheaths of strobilae, equivalent to the collagenous peridermal sheaths of the polyps of extant coronate scyphozoans such as Stephanoscyphus [19] and Thecoscyphus [20]. Direct evidence of a cnidarian affinity has been lacking for Olivooides and so the comparison to coronate scyphozoans was substantiated on a chain of inference based on initial comparisons to conulariids and conulariid-like fossils, which are found in the same deposits as Olivooides (hexangulaconulariids and carinachitids; see [21,22]). Their shared similarities include an annulated conical test, fine longitudinal sculpture and a bluntly tapering apex with radial folds. Conulariids, in turn, share characteristics with coronate scyphozoans including, in particular, a conical, two-layered, peridermal sheath ornamented with transverse annulations and fine longitudinal striations, that completely encloses the polyp, as well as evidence of strobilation; certain conulariids and coronates also exhibit tetramerally arranged internal peridermal projections, seriated in coronates and some but not all conulariids, and located in conulariids at positions interpreted as homologous to the perradii and interradii of coronates and other scyphozoans [23,24–27].

Evidence for a cnidarian affinity for conulariids may be compelling because of their similarities to coronate scyphozoans [26,28,29]. However, some of these characters appear to be shared primitive characters of medusozoans. Thus, based on the available evidence, the classification of conulariids may not be secure beyond the level of total group Medusozoa [25]. Olivooides possesses only a subset of the characters shared by conulariids and coronate scyphozoans and, furthermore, the suite of characters known hitherto has not been sufficient to substantiate an a priori comparison with Cnidaria. Yue & Bengtson [5] noted that Olivooides differs from extant coronate scyphozoans in a number of ways. Foremost, the pentaradial symmetry exhibited by Olivooides is not typical of Cnidaria, less so coronate scyphozoans. However, cnidarians exhibit diverse symmetries, and pentaradial symmetry occurs not only within populations with fluctuating symmetry [29,30], but also as the normal condition in some species [31]. Furthermore, Olivooides co-occurs in fossil assemblages with Quadrapyrgites nigqiangensis [13,32] that is comparable with the exception that it exhibits tetraradial symmetry. Additional problems with the cnidarian interpretation of Olivooides include the stellate tissue seen in the embryonic and putative polyp stages, which has no equivalent in the periderm of coronate scyphozoan polyps, and the absence in Olivooides of the attachment structure seen in polyps of extant coronate scyphozoans. These could be reconciled as autapomorphies of Olivooides, though similar structures, comprising twisted clusters of actin filaments, occur in association with the egg cases of anthozoans [33,34].

Our new data on the internal anatomy of the putative–embryonic stages of Olivooides demonstrate that the pentaradial symmetry of the outer, stellate tissue layer is not superficial, but a reflection of the fundamental symmetry imposed on all aspects of the anatomy of this organism. Within the cnidarian interpretative milieu, we interpret the preserved internal anatomy to reflect the gastrodermis, preserving the course of passage of radial canals, the paired lobes representing peridermal teeth and the aboral region representing the position of the pharyngeal lumen from which rises the axial pentaradial structures that perhaps supported mesenteries, or else represents a manubrium. Following the latter interpretation, the pentaradially subdivided space between the inner and outer walls might represent the mesenteries.

The free-living stage is obviously readily reconcilable within a cnidarian interpretative framework, with its two whorls reflecting two adpressed ephyra larvae (juvenile medusae) produced through a strobilation process by a pentaradial cnidarian.

5. Discussion

Of the three competing hypotheses of affinity, the anatomical evidence for Olivooides is most readily reconciled with the cnidarian interpretative model. Indeed, our observations facilitate a more comfortable classification of Olivooides within Cnidaria generally, and among medusozoans and coronate scyphozoans more specifically. The discovery of an ephyra-like stage associated with Olivooides removes equivocation over the appropriateness of the cnidarian interpretation and so substantiates closer comparison with medusozoans. In particular, the peridermal sheath of Olivooides was not mineralized in vivo and has a circular cross section, as it is in coronate scyphozoans [1,5]. The presence of peridermal tooth-like structures in Olivooides draws further comparison with scyphozoan cnidarians. The complete enclosure of the peridermal polyp sheath of Olivooides is analogous to the opercular disc of scyphozoans such as Nausithoe planulophora, which develops from the terminal polyp to seal the peridermal sheath for over-wintering [29]. In Olivooides, the complex folding seen at the aperture of the peridermal sheath more closely resembles embryonic stages where striate tissue is preformed within, before unfolding to extend the length of the polyp sheath. While there is evidence that the aperture of the post-embryonic polyp sheath was entirely open in some stages of Olivooides, there is no evidence of an opercular plate. Indeed, the presence of an opercular plate is not compatible with developmental stages in which the aperture is closed by unfolding striate tissue. The available evidence indicates that the folded aperture of the ‘Punctatus’ stage in Olivooides represents an episodic phase related to the growth of the peridermal sheath.

The free-living ephyra larva-like stage is especially compatible with existing interpretation of the embryology of Olivooides which inferred the existence of a medusoid sexual reproductive phase alternating with direct development from embryo to polyp [1,5]. This was originally interpreted to reflect retention of direct development from ancestral metazoans [1,5], but it more likely represents loss of the asexual planula stage, which is general and therefore presumably primitive to medusozoans. Development without a ciliated planula larva has evolved in at least three cnidarian clades: Actinulida [35], Aplanulata [36] and Stauromedusae [37]. Each of these groups has a distinctive pattern of development, viz. Actinulida develop directly into an adult with a mixture of polyp and medusa characters [35], Aplanulata form a cuticle stage after gastrulation from which emerges a hatchling that begins to develop tentacle bumps [36], whereas Stauromedusae have planulae that are unciliated.

6. Conclusions

We extend our knowledge of Olivooides anatomy and development with the first insights into internal anatomy and description of new developmental stages. These demonstrate that the pentaradial symmetry of the outer integument of the stellate and conical stages is a reflection of a fundamental symmetry that is observed in all aspects of anatomy. Together with the presence of a free-swimming, pentaradial medusoid stage, we reject the proposed scalidophoran and echinoderm affinity of Olivooides in favour of a scyphozoan cnidarian phylogenetic hypothesis. The pentaradial symmetry of Olivooides is not characteristic of cnidarians generally, or scyphozoans in particular. This discrepancy is readily rationalized because the stages in the development of pentaradial Olivooides are paralleled by the co-occuring tetraradial Quadrapyrgites. However, our additional data on the embryology of Olivooides has only added further evidence of direct development, from embryo to polyp. This remains uncharacteristic of cnidarians and scyphozoans more specifically, where the mode of indirect development, with an intermediate planula larva, is presumed plesiomorphic. Either Olivooides and Quadrapyrgites are members of a Cambrian lineage in which the planula stage has been lost secondarily, or perhaps these data hint that scyphozoans, cnidarians and perhaps eumetazoans primitively had a life history of direct development.

Acknowledgements

We thank Federica Marone and Neil Gostling for assistance at the beamline, and Jenny Greenwood for help with picking. Our interpretation of the fossil remains benefited from discussion with Allen Collins, Annalise Nawrocki and Shuhai Xiao; Nigel Hughes provided constructive comments in review. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 41072006 to X.P.D.), State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. 103102 to X.P.D.), the Research Fund for Doctoral Program of High Education (grant no. 20060001059 to X.P.D.), a Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) Standard grant (no. NE/F00348X/1 to P.C.J.D.), a NERC studentship (to C.W.-T.), as well as through a beam time allocation on the TOMCAT beamline of the Swiss Light Source, courtesy of the Paul Scherrer Institut (to P.C.J.D. and S.B.).

References

- 1.Bengtson S, Yue Z. 1997. Fossilized metazoan embryos from the earliest Cambrian. Science 277, 1645–1648 10.1126/science.277.5332.1645 (doi:10.1126/science.277.5332.1645) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiao S, Zhang Y, Knoll AH. 1998. Three-dimensional preservation of algae and animal embryos in a Neoproterozoic phosphate. Nature 391, 553–558 10.1038/35318 (doi:10.1038/35318) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dong X-P, Donoghue PCJ, Cheng H, Liu J. 2004. Fossil embryos from the Middle and Late Cambrian period of Hunan, south China. Nature 427, 237–240 10.1038/nature02215 (doi:10.1038/nature02215) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donoghue PCJ, Dong X-P. 2005. Embryos and ancestors. In Evolving form and function: fossils and development (ed. Briggs DEG.), pp. 81–99 New Haven, CT: Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yue Z, Bengtson S. 1999. Embryonic and post-embryonic development of the Early Cambrian cnidarian Olivooides. Lethaia 32, 181–195 10.1111/j.1502-3931.1999.tb00538.x (doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1999.tb00538.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conway Morris S. 1998. Eggs and embryos from the Cambrian. BioEssays 20, 676–682 (doi:10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199808)20:8<676::AID-BIES11>3.0.CO;2-W) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steiner M, Li G, Hu S. 2010. Soft tissue preservation in small shelly faunas. GSA Abstr. Program. 42, 359 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen JY. 2004. The dawn of animal world. Nanjing, China: Jiangsu Science and Technology Press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donoghue PCJ, et al. 2006. Synchrotron X-ray tomographic microscopy of fossil embryos. Nature 442, 680–683 10.1038/nature04890 (doi:10.1038/nature04890) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stampanoni M, Borchert G, Wyss P, Abela R, Patterson B, Hunt S, Vermeulen D, Rüegsegger P. 2002. High resolution X-ray detector for synchrotron-based microtomography. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A Accel. Spectrom. Detect. Assoc. Equip. 491, 291–301 10.1016/S0168-9002(02)01167-1 (doi:10.1016/S0168-9002(02)01167-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stampanoni M, et al. 2007. TOMCAT: a beamline for TOmographic Microscopy and Coherent rAdiology experimenTs. Sync. Rad. Instrum. 879, 848–851 10.1063/1.2436193 (doi:10.1063/1.2436193) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steiner M, Zhu M, Li G, Qian Y, Erdtmann B-D. 2004. New early Cambrian bilaterian embryos and larvae from China. Geology 32, 833–836 10.1130/G20567.1 (doi:10.1130/G20567.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen F, Dong X-P. 2008. The internal structure of Early Cambrian fossil embryo Olivooides revealed in the light of synchrotron X-ray tomographic microscopy. Chin. Sci. Bull. 53, 3860–3865 10.1007/s11434-008-0452-9 (doi:10.1007/s11434-008-0452-9) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Storch V. 1991. Priapulida. In Microscopic anatomy of invertebrates vol. 6: Aschelminthes (eds Harrison FW, Ruppert EA.), pp. 333–350 New York, NY: Wiley-Liss [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins RP, Storch V. 1991. Evidence for direct development in Meiopriapulus fijiensis (Priapulida). Trans. Am. Microsc. Soc. 110, 37–46 10.2307/3226738 (doi:10.2307/3226738) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shirley TC. 2002. Phylum Priapulida. In Atlas of marine invertebrate larvae (ed. Young CM.), pp. 189–194 San Diego, CA: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manuel M. 2009. Early evolution of symmetry and polarity in metazoan body plans. CR Biol. 332, 184–209 10.1016/j.crvi.2008.07.009 (doi:10.1016/j.crvi.2008.07.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith AB. 2008. Deuterostomes in a twist: the origins of a radical new body plan. Evol. Dev. 10, 493–503 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00260.x (doi:10.1111/j.1525-142X.2008.00260.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman DM, Werner B. 1972. Structure of a solitary and a colonial species of Stephanoscyphus (Scyphozoa, Coronatae) with observations on periderm repair. Helgoländer Wiss. Meeresuntersuchungen 23, 393–421 10.1007/BF01625293 (doi:10.1007/BF01625293) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sötje I, Jarms G. 2009. Derivation of the reduced life cycle of Thecoscyphus zibrowii Werner, 1984 (Cnidaria, Scyphozoa). Mar. Biol. 156, 2331–2341 10.1007/s00227-009-1261-7 (doi:10.1007/s00227-009-1261-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conway Morris S, Chen M. 1992. Carinachitids, Hexangulaconulariids, and Punctatus: problematic metazoans from the Early Cambrian of South China. J. Paleontol. 66, 384–406 [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Iten H, Maoyan Z, Li GX. 2010. Redescription of Hexaconularia He and Yang, 1986 (Lower Cambrian, South China): implications for the affinities of conulariid-like small shelly fossils. Palaeontology 53, 191–199 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00925.x (doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00925.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Iten H. 1992. Microstructure and growth of the conulariid test: implications for conulariid affinities. Palaeontology 35, 359–372 [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Iten H, Cox RS. 1992. Evidence of clonal budding in a radial cluster of Paraconularia crustula (White) (Pennsylvanian, questionable-Cnidaria). Lethaia 25, 421–426 10.1111/j.1502-3931.1992.tb01645.x (doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1992.tb01645.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Iten H, Leme JdM, Simòes MG, Marques AC, Collins AG. 2006. Reassessment of the phylogenetic position of conulariids (?Ediacaran–Triassic) within the subphylum Medusozoa (Phylum Cnidaria). J. Syst. Palaeontol. 4, 109–118 10.1017/S1477201905001793 (doi:10.1017/S1477201905001793) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Werner B. 1966. Stephanoscyphus (Scyphozoa, Coronatae) und seine direktz Abstammung von den fossiten Conulata. Helgoländer Wiss. Meeresuntersuchungen 13, 317–347 10.1007/BF01611953 (doi:10.1007/BF01611953) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leme JD, Simoes MG, Rodrigues SC, van Iten H, Marques AC. 2008. Major developments in conulariid research: problems of interpretation and future perspectives. Ameghiniana 45, 407–420 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Werner B. 1970. Contribution to the evolution in the genus Stephanoscyphus (Scyphozoa Coronatae) and ecology and regeneration qualities of Stephanoscyphus racemosus Komai. Publ. Seto Mar. Biol. Lab. 18, 1–20 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Werner B. 1973. New investigations on systematics and evolution of the Class Scyphozoa and the Phylum Cnidaria. Publ. Seto Mar. Biol. Lab. 20, 35–61 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gershwin L-A. 1999. Clonal and population variation in jellyfish symmetry. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 79, 995–1000 10.1017/S002515499001228 (doi:10.1017/S002515499001228) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uchida T. 1928. Short notes on medusae. I. Medusae with abnormal symmetry. Annot. Zool. Japon. 2, 373–376 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li P, Hua H, Zhang LY, Zhang DD, Jin XB, Liu Z. 2007. Lower Cambrian phosphatized Punctatus from southern Shaanxi and their ontogeny sequence. Chin. Sci. Bull. 52, 2820–2828 10.1007/s11434-007-0447-y (doi:10.1007/s11434-007-0447-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spaulding JG. 1972. The life cycle of Peachia quinquecapitata, an anemone parasitic on medusae during its larval development. Biol. Bull. 143, 440–453 10.2307/1540065 (doi:10.2307/1540065) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dewel WC, Clarke WH., Jr 1974. A fine structural investigation of surface specializations and the cortical reactions in eggs of the cnidarian Bunodosoma cavernata. J. Cell Biol. 60, 78–91 10.1083/jcb.60.1.78 (doi:10.1083/jcb.60.1.78) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Swedmark B, Teissier G. 1966. The Actinulida and their evolutionary significance in the Cnidaria. In The Cnidaria and their evolution (ed. Rees WJ.), pp. 119–133 London, UK: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin VJ, Littlefield CL, Archer WE, Bode HR. 1997. Embryogenesis in hydra. Biol. Bull. 192, 345–363 10.2307/1542745 (doi:10.2307/1542745) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Otto JJ. 1976. Early development and planula movement in Haliclystus (Scyphozoa: Stauromedusae). In Coelenterate ecology and behavior (ed. Mackie GO.), pp. 319–329 New York, NY: Plenum Press [Google Scholar]