Abstract

Hornworts are considered the sister group to vascular plants, but their fungal associations remain largely unexplored. The ancestral symbiotic condition for all plants is, nonetheless, widely assumed to be arbuscular mycorrhizal with Glomeromycota fungi. Owing to a recent report of other fungi in some non-vascular plants, here we investigate the fungi associated with diverse hornworts worldwide, using electron microscopy and molecular phylogenetics. We found that both Glomeromycota and Mucoromycotina fungi can form symbioses with most hornworts, often simultaneously. This discovery indicates that ancient terrestrial plants relied on a wider and more versatile symbiotic repertoire than previously thought, and it highlights the so far unappreciated ecological and evolutionary role of Mucoromycotina fungi.

Keywords: arbuscular mycorrhizas, Endogone, evolution, fungi, plants, symbiosis

1. Introduction

Hornworts (Anthocerotophyta) are an ancient phylum, approximately 300–400 million years old, now considered sister to the earliest vascular plants [1–6]. They have a worldwide distribution in moist temperate and tropical habitats as pioneer colonizers of nutrient-poor substrates. Having thalloid gametophytes and persistent sporophytes, hornworts are key to understanding the transformation from the gametophyte-dominated life cycles of non-vascular plants to the sporophyte-dominated life cycles of vascular plants [7].

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (Glomeromycota) [8] are the prevalent symbionts of extant vascular plants and the early-diverging lineages of the major clades (simple and complex thalloid liverworts, lycophytes and ferns). Thus, identification of mycorrhizal fungi within plants relies routinely on Glomeromycota-specific detection. Glomeromycota were firmly regarded as the ancestral mycorrhizal type [9,10] until the recent discovery of Endogone-like Mucoromycotina fungi in the earliest liverwort lineage (Haplomitriopsida) and in some early simple and complex thalloid liverworts questioned that idea [11]. Glomeromycota fungi are reported to associate with five hornworts, based on electron microscope [12], in vitro [13] and molecular studies [11]. However, two hornworts are reported to harbour Endogone-like fungi [11] and two others are considered non-symbiotic [14,15]. We ignore the fungal symbioses of the vast majority of the 200–220 hornwort species, though the scanty information to date hints at some parallels with liverworts. Furthermore, while knowledge of Glomeromycota arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi has blossomed ever since they were taxonomically separated from Endogone [16], the latter have become grossly neglected. Because the information available is insufficient to understand the symbiotic past and present of fungi, hornworts and vascular plants, here we carry out the first global molecular and cytological analysis of hornworts (table 1; electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S2) designed to test their symbioses.

Table 1.

Summary of the hornworts sampled, subdivided by species and the fungal status of each species. The number of samples within each fungal clade is in brackets.

| organism | location | sample number | Glomeromycota | Mucoromycotina |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthoceros sp. | Ascension Island, Malaysia, South Africa | 5 | Archaeosporaceae (1), Claroideoglomeraceae (1), Paraglomeraceae (1) | group A (3), B (1), D (1), Mucoromycotina (1) |

| Anthoceros agrestis | China, England, Scotland | 4 | Acaulosporaceae (1), undescribed Archaeosporales (2), Claroideoglomeraceae (3) | group A (3) |

| Anthoceros fusiformis | USA | 2 | n.d. | group B (1), D (1) |

| Anthoceros lamellatus | Panama | 1 | Archaeosporaceae (1) | group D (1) |

| Anthoceros laminiferus | New Zealand | 16 | Acaulosporaceae (1), Archaeosporaceae (1), Claroideoglomeraceae (1) | group A (2), C (1), I (1), Mucoromycotina (1) |

| Anthoceros punctatus | Scotland, South Africa, USA, Wales | 7 | Acaulosporaceae (2), Archaeosporaceae (1), Archaeosporales (1), Claroideoglomeraceae (1), Glomeraceae (3) | group A (2) |

| Dendroceros crispus | Panama | 1 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Dendroceros validus | Malaysia | 1 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Folioceros sp. | Malaysia | 3 | Claroideoglomeraceae (1), Glomeraceae (2) | group E (1) |

| Folioceros fuciformis | China, Malaysia | 6 | undescribed Archaeosporales (2), Glomeraceae (3) | n.d. |

| Leiosporoceros dussii | Panama | 1 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Megaceros sp. | New Zealand | 9 | Archaeosporaceae (1), Glomeraceae (1) | group B (1), C (1), Mucoromycotina (2) |

| Megaceros flagellaris | Australia, Malaysia | 4 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Megaceros leptohymenius | New Zealand | 18 | undescribed Archaeosporales (1), Claroideoglomeraceae (1), Glomeraceae (2) | group A (1), C (3), Mucoromycotina (2) |

| Megaceros pellucidus | New Zealand | 9 | undescribed Archaeosporales (1) | group C (1), F (1) |

| Nothoceros giganteus | New Zealand | 3 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Nothoceros vincentianus | Panama | 4 | Acaulosporaceae (1), Glomeraceae (1) | group F (1), Mucoromycotina (1) |

| Notothylas javanica | Panama | 1 | Diversisporaceae (1) | n.d. |

| Notothylas orbicularis | Panama | 1 | Glomeraceae (1) | n.d. |

| Phaeoceros sp. | China | 1 | Glomeraceae (1) | group B (1) |

| Phaeoceros carolinianus | Ascension Island, Australia, China, Italy, Malaysia, New Zealand, Panama, South Africa, USA | 58 | Acaulosporaceae (9), Archaeosporaceae (9), undescribed Archaeosporales (4), Claroideoglomeraceae (10), Glomeraceae (21) | group A (10), B (9), C (4), D (5), F (1), G (1), Mucoromycotina (5) |

| Phaeoceros dendroceroides | Panama | 2 | Archaeosporaceae (1), Claroideoglomeraceae (1) | group B (1), E (1) |

| Phaeoceros laevis | China, England, Falkland Islands, Scotland, Wales | 13 | Archaeosporaceae (3), Claroideoglomeraceae (1), Glomeraceae (2) | group A (4), B (2), I (1) |

| Phaeoceros (Paraphymatoceros) pearsonii | USA | 1 | n.d. | n.d. |

| Phaeomegaceros sp. | Australia, Malaysia | 2 | Glomeraceae (1) | group D (1) |

| Phaeomegaceros coriaceus | New Zealand | 19 | Acaulosporaceae (3), Archaeosporaceae (1), undescribed Archaeosporales (1), Claroideoglomeraceae (1), Glomeraceae (5) | group A (5), B (3), C (2), D (1), E (1), F (1), G (2), H (2), I (1), L (1), Mucoromycotina (3) |

| Phaeomegaceros hirticalyx | New Zealand | 7 | n.d. | group C (1) |

2. Material and methods

(a). Sampling

At each of nearly 200 sites, we collected at least one colony of each hornwort species. Each collection was subsampled within one week, cleaned with forceps and rinsed in distilled water. Fungal fruitbodies were obtained from public and personal collections. Plant vouchers are in the herbarium of the Natural History Museum.

(b). Ultrastructural analysis

Preparation of samples for transmission electron microscopy followed Ligrone & Duckett [17]. Healthy thalli were fixed in 3 per cent glutaraldehyde, 1 per cent fresh formaldehyde and 0.75 per cent tannic acid in 0.05 M Na–cacodylate buffer, pH 7, for 3 h at room temperature. After rinses in 0.1 M buffer, the samples were postfixed in buffered (0.1 M, pH 6.8) 1 per cent osmium tetroxide overnight at 4°C, dehydrated in an ethanol series and embedded in Spurr's resin via ethanol. Thin sections were cut with a diamond knife, stained with methanolic uranyl acetate for 15 min and in Reynolds' lead citrate for 10 min, and observed with a Hitachi H-7100 transmission electron microscope at 100 kV. For cryo-scanning electron microscopy, the protocol of Duckett et al. [18] was followed. For light microscopy, 0.5 µm thick sections were cut with a diamond histo-knife, stained with 0.5 per cent toluidine blue and photographed with a Zeiss Axioskop light microscope fitted with an MRc Axiocam digital camera.

(c). Fungal detection and identification

A 2–3 mm section of the colonized part of each thallus was placed in 300 µl cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) extraction buffer and stored at −80°C until use. Genomic DNA was extracted from one to three thallus fragments from each collection with the method of Gardes & Bruns [19] but using GeneClean (QBioGene) for purification. The same protocol was used for 1–2 mm inner fragments of each fungal fruitbody. Fungal 18S ribosomal DNA was amplified using JumpStart (Sigma) with primers NS1 [20] and EF3 [21] by 94°C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, 54°C for 30 s, 72 min for 1 min 45 s and a final step at 72°C for 7 min. Universal fungal primers failed to amplify most samples; thus, we applied nested PCR with additional 18S primer sets: AML1–AML2 [22] to detect Glomeromycota, and EndAD1f (5′-GTAGTTGAATTTTAGCCYTGGCT-3′) and EndAD2r (5′-ACCTTCCGGCCAAGGTTATARAC-3′) to detect Endogonales. For nested PCR, Glomeromycota 18S was first amplified using PicoMaxx high fidelity (Agilent Technologies) with NS1 [20] and EF3 [21] by 95°C for 2 min, 30 cycles of 95°C for 40 s, 58°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min 45 s and a final step at 72°C for 7 min. Subsequently, products were nested using JumpStart with AML1–AML2 [22] by 94°C for 4 min, 28 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, 72°C for 50 s with a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. Endogonales 18S was first amplified using PicoMaxx with EndAD1f and NS8 [20]. The cycling conditions were as mentioned earlier with annealing at 63°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 1 min 20 s. Products were then nested using JumpStart with EndAD1f and EndAD2r (approx. 890 bp) by 94°C for 4 min, 27 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 63°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1 min and a final step of 72°C for 7 min. All products from fungal, Glomeromycota and Endogonales amplifications were cloned with TOPO TA cloning kit for sequencing (Invitrogen), and at least four clones, for each sample, were sequenced with BigDye v. 3.1 on an ABI3730 genetic analyser (Applied Biosystems).

(d). Bioinformatics

The DNA sequences were assembled and curated using BioEdit v. 7.1.3 [23] and Mega v. 5 [24], aligned using MUSCLE [25] or webPrank [26], and compared by BLAST [27] against the INSD [28]. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted separately for Glomeromycota and Mucoromycotina. Phylogenies were inferred with RaxmlGUI v. 1.3 [29] and MrBayes v. 3.1.2 [30], using jModelTest v. 2.1.1 [31] to choose best-fit models of nucleotide substitution. The GTR + G model was chosen for both analyses. A total of 1000 bootstrap replicates were performed for trees constructed with RaxmlGUI, whereas the Markov chain Monte Carlo was run for 10 million generations. For both Glomeromycota and Mucoromycotina, two phylogenetic analyses were conducted: the first using representative DNA sequences of each clade and the second using all sequences. Alignments and trees are available in TreeBASE (submission 13945) [32]. Representative DNA sequences are in GenBank (KC708342–KC708444).

(e). Inferring symbiotic history

We sampled 26 hornwort DNA accessions (see the electronic supplementary material, table S1). As outgroups, we included five taxa representing early land plants (liverworts, mosses) and seedless vascular plants (lycopods, ferns; electronic supplementary material, table S1). Whenever possible, we used the collection from which fungal data were obtained. Plant genomic DNA isolation followed protocols described by Duff et al. [33,34]; newly generated DNA sequences are in GenBank (JX885632–JX885643). To infer phylogenetic relationships, we used the plastid gene rbcL. Sequence editing and alignment were carried out in Geneious v. 5.5.6 and alignments are in TreeBASE (submission 13455) [32]. Phylogenetic analyses were performed under likelihood (ML) optimization and the GTR + G substitution model using RAxML [35]. Statistical support was assessed via 100 ML bootstrap replicates and the same substitution model. Each tree tip was scored for fungal absence or presence based on molecular and microscopy data. Ancestral reconstructions of Glomeromycota and Mucoromycotina were carried out separately relying on ML as implemented in Mesquite using the Markov 1-parameter model [36], the highest likelihood tree from RAxML and parameters estimated from data. An asymmetrical two-rate parameter model was also used with similar results.

3. Results

(a). Fungal colonization of hornworts

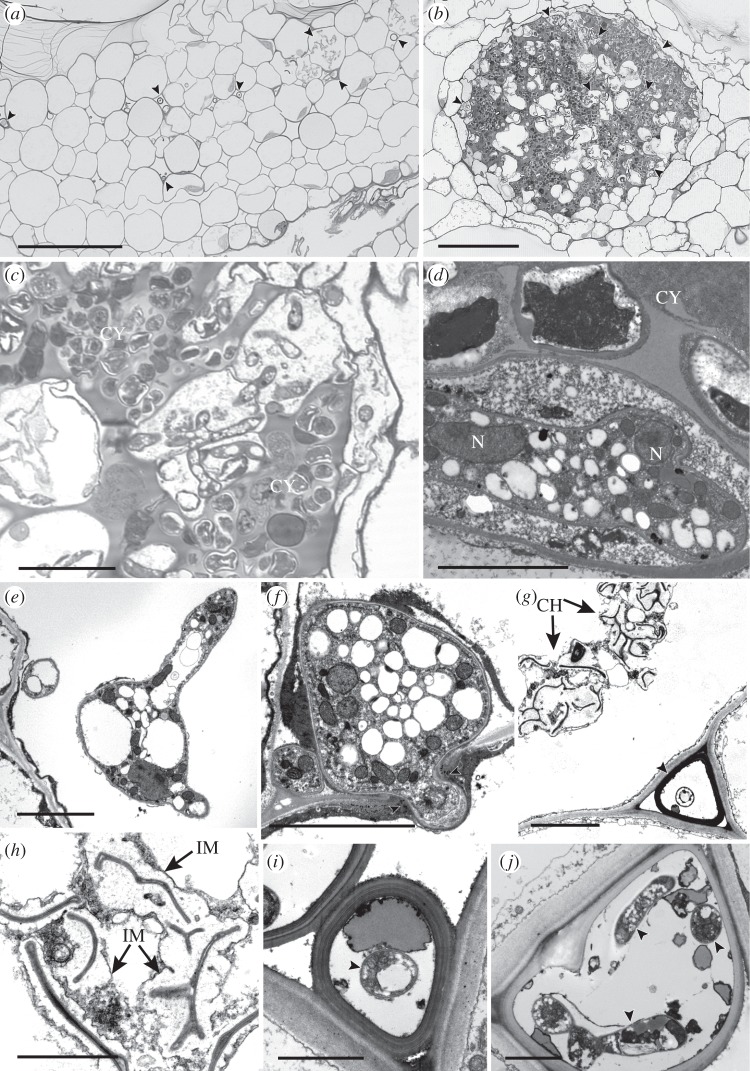

We collected 199 hornworts of over 20 species, in 10 of the 12 described genera, from six continents (see the electronic supplementary material, table S2). Fungal hyphae are inter- and intracellular in the central parts of thalli that bear numerous rhizoids, from above the ventral epidermis to the base of the large genus-diagnostic mucilage chambers (figure 1a), and cyanobacterial colonies (figure 1b–d; electronic supplementary material, figure S1a–c). Intracellularly, thin-walled and often branching hyphae form swellings and vesicles (figure 1e,d; electronic supplementary material, figure S1e–g); cells just below the mucilage chambers mainly contain collapsed fungal remains (figure 1g,h). In the intercellular spaces, in close proximity to host cell walls, both thin-walled hyphae (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S2b) and fungal structures with thick multi-layered walls are present (figure 1g,i,j; electronic supplementary material, figure S2a). The latter often have thin-walled hyphae in their lumina (figure 1i,j). Intracellular hyphae intimately associated with plant cell walls (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S2c) or penetrating cells (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S2d) are common.

Figure 1.

(a–c) Light and (d–j) transmission electron micrographs of fungal endophytes in (a,g,h) Folioceros (MA33) and in (b–f) Anthoceros (MA29). (a–c) Fungal hyphae occur either (a) scattered in the central region of the thallus (arrowed) or (b) in close association with cyanobacterial colonies (CY; arrowed, enlarged in c). (d) Multi-nucleate hypha (N, nucleus) in cell adjacent to a cyanobacterial colony (CY). (e,f) Intracellular hyphae; (e) branched hypha and (f) hypha bridging the walls (arrowed) of two adjacent host cells. (g) Thick-walled fungal structure in mucilage-filled intercellular space (arrowed) adjacent to intracellular collapsed hyphae (CH). (h) Detail of collapsed intracellular hyphae, note the extensive interfacial matrix (IM). (g,j) Intercellular thick-walled fungal structures with internal thin-walled hyphae (arrowed). Scale bars: (a,b) 100 µm, (c) 20 µm, (d–g) 5 µm, (h–j) 2 µm.

(b). Identification of fungi

We found that 121 of 199 samples were colonized by Glomeromycota and/or Mucoromycotina. Fifty samples were associated with both, whereas 42 and 29 samples harboured only Glomeromycota or Mucoromycotina, respectively (see the electronic supplementary material, table S2). Anthoceros, Folioceros, Notothylas, Phaeoceros and Phaeomegaceros were abundantly colonized by fungi, Megaceros and Nothoceros were occasionally colonized, and Dendroceros validus, D. crispus, Leiosporoceros dussii, Megaceros flagellaris, Nothoceros giganteus and Phaeoceros (Paraphymatoceros) pearsonii were not colonized.

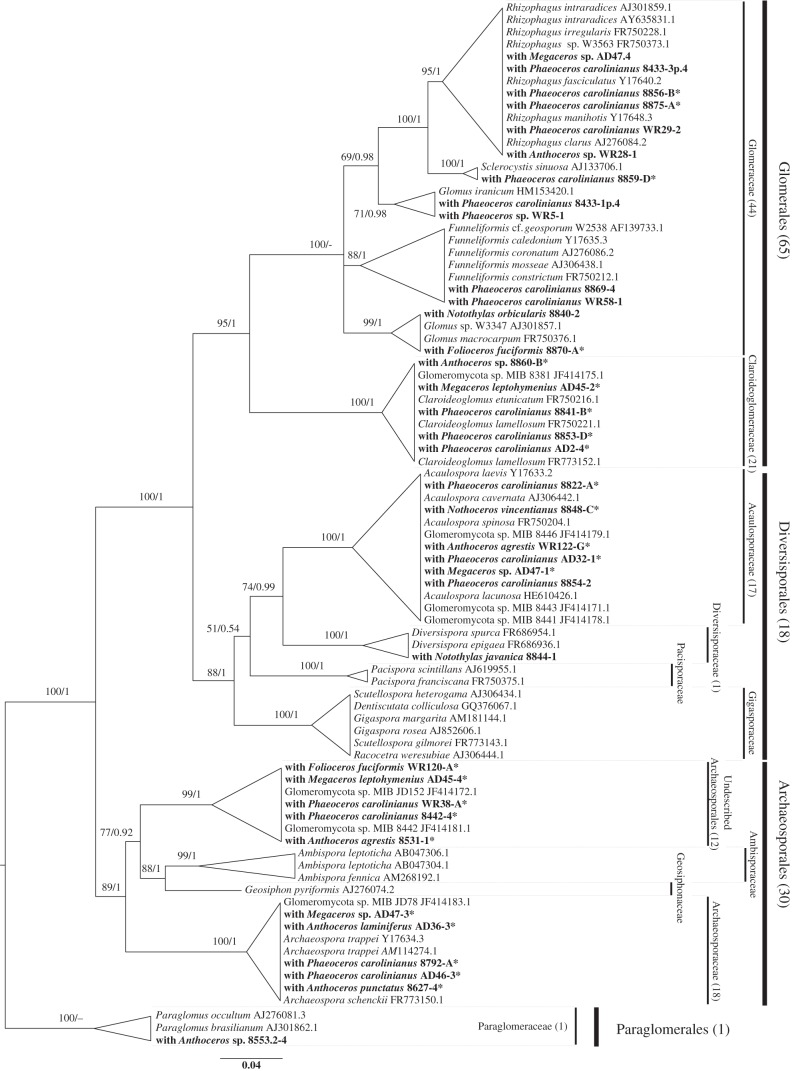

We detected fungi from each of the four Glomeromycota orders (figure 2; electronic supplementary material, figure S3, and tables S1 and S2). The fungi in most hornwort samples (65 samples) belonged to Glomerales in each of its five genera [37]. The fungi from 30 hornwort samples were Archaeosporales, in the Archaeospora clade, and in a clade sister to Ambispora and Geosiphon [37]. The fungi from 18 hornwort samples were Diversisporales (17 in the Acaulosporaceae and one in the Diversisporaceae). Paraglomerales were detected in one sample.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic placement of representative Glomeromycota fungi retrieved from hornworts. The tree encompasses different subclades, as in the study by Krüger et al. [37]. The DNA sequences retrieved from hornworts are in bold. Support values are from maximum-likelihood/Bayesian analyses. Dashes instead of numbers imply that the topology was not supported in the respective analysis. Numbers of retrieved sequences belonging to each Glomeromycota family/order are in brackets. The sequences marked with an asterisk were retrieved using fungal primers NS1-EF3 [20,21].

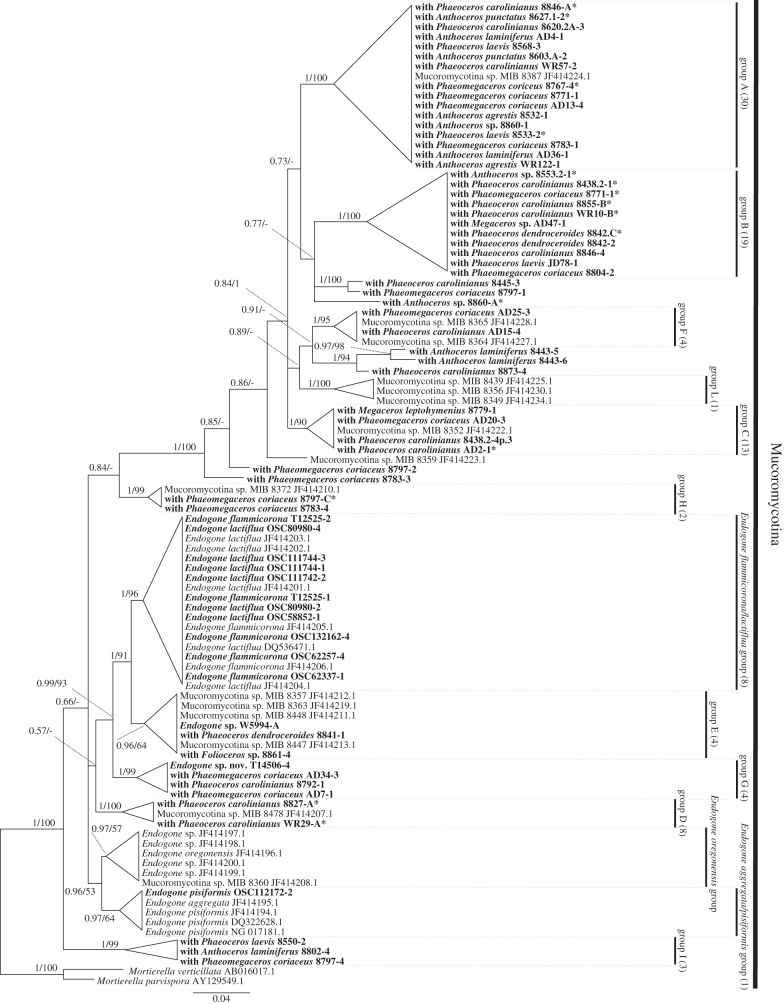

We detected 13 Mucoromycotina clades supported by strong bootstrap/posterior probability values and with sequences from at least three different samples (figure 3; electronic supplementary material, figure S4, and tables S1 and S2). These comprise the Endogone-like clades detected by Bidartondo et al. [11] and three new clades (B, G and I). Three clades include fruitbodies of described Endogone: E. aggregata/E. pisiformis, E. flammicorona/E. lactiflua and E. oregonensis. Only two other Endogone sp. fruitbodies (W5994 and T14506) are present in the tree, in clades E and G, respectively. The remaining eight clades have only fungal DNA sequences retrieved from plants (figure 3; electronic supplementary material, figure S4). The new primers turned out to be also effective for the amplification of 10 decades-old Endogone fruitbodies.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic placement of representative Endogone-like fungi detected in hornworts within the Mucoromycotina clade. The tree has 13 clades. The DNA sequences retrieved from hornworts are in bold. Support values are from Bayesian/maximum-likelihood analyses. Dashes instead of numbers imply that the topology was not supported in the respective analysis. Numbers of retrieved sequences belonging to each group are in brackets. Sequences marked with an asterisk were retrieved using fungal primers NS1-EF3 [20,21].

(c). Symbiotic history of fungi and hornworts

Uncertainty (ML prob. = 0.50) in ancestral reconstruction analyses does not allow us to state conclusively whether Glomeromycota or Mucoromycotina (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S5 and table S3) were present in the ancestor of hornworts. Maximum-likelihood reconstruction (see the electronic supplementary material, figure S5 and table S3) moderately supports the presence of Glomeromycota in the ancestor of Anthocerotaceae (ML prob. = 0.56), Dendrocerotaceae (ML prob. = 0.73), Megaceros (ML prob. = 0.62) and Phaeoceros (ML prob. = 0.99). If Glomeromycota were ancestral in hornworts, they were lost at least five times. In turn, colonization by Mucoromycotina may have evolved three to four times from a non-symbiotic plant ancestor. Similarly, our analyses indicate Mucoromycotina were acquired independently in Anthoceros, excluding Folioceros (ML prob. = 0.72; but higher in the ancestor of the A. agrestis–punctatus group, ML prob. = 0.99), Phaeoceros (ML prob. = 0.99) and the ancestor of Dendrocerotaceae with moderate support (ML prob. = 0.74; electronic supplementary material, table S3). The alternative scenario would be ancestral Mucoromycotina with subsequent losses in Leiosporoceros, Nothoceros, Dendroceros, Megaceros flagellaris, Notothylas and P. pearsonii.

4. Discussion

The first systematic study of fungi in hornworts reveals that this ancient plant lineage has developed a variety of symbiotic strategies. Hornworts form symbioses with (i) nearly all clades of the arbuscular mycorrhizal phylum Glomeromycota, (ii) unexpectedly diverse members of the unplaced subdivision Mucoromycotina, both closely and distantly related to Endogone, (iii) both Glomeromycota and Mucoromycotina, or (iv) neither Glomeromycota nor Mucoromycotina. This shifting symbiotic scenario contrasts with the conservatism of liverwort–basidiomycete symbioses [38], liverwort–Mucoromycotina symbioses in the earliest land plant lineages [11], and with the symbioses of later thalloid liverworts and vascular plants, where mycorrhizal symbioses with Glomeromycota are nearly ubiquitous and only a few recent lineages have switched to Basidiomycota, Ascomycota or to being non-mycorrhizal. Trappe [39] first reported that arbuscular mycorrhizas are the ancestral mycorrhiza in angiosperms. A vast survey by Wang & Qiu [9] confidently extended this notion to all land plants. However, the results presented here further reinforce the recent discovery that Glomeromycota were not the only symbiotic fungi involved in early plant evolution [11]. Mucoromycotina probably preceded the Glomeromycota in liverworts, and in hornworts either group may have been ancestral.

Cytological features characteristic of Glomeromycota and Mucoromycotina agree with molecular data. Large vesicles filling plant cells are diagnostic of Glomeromycota. Intracellular fungal swellings plus thin-walled hyphae and thick-walled fungal structures in small mucilage-filled intercellular spaces are typical not only of Mucoromycotina in the basal liverwort Treubia [40,41] but also of fungi in the Devonian fossil plant Nothia [42,43]. The ultrastructure of hornwort symbionts is also similar to that of the spores of Endogone flammicorona sporocarps [44]. The principal mode of fungal entry in hornworts may well be via mucilage clefts [12], in contrast to rhizoidal entry in the majority of liverworts. It is noteworthy that, as in liverworts, hornworts that are either epiphytic and epiphyllous (Dendroceros) or with thalli growing either over other bryophytes (Nothoceros) or in very wet places (Megaceros) usually lack fungi [41].

In liverworts, fungal symbioses are either obligate or absent in different taxa, and fungi occupy specific regions of the thalli or stems [41]. By contrast, fungi in hornworts are more capricious; inter- and intracellular hyphae are usually present in the central parts of thalli in regions with numerous rhizoids and extend from subepidermal layers to the base, but not into large mucilage cavities, when present (e.g. Anthoceros). Hyphae are also closely associated with cyanobacteria, suggesting a relationship resembling that of the only non-mycorrhizal glomeromycete, Geosiphon, which is symbiotic with cyanobacteria [45]. A functional relationship between fungi and cyanobacteria may also explain the absence of the former in some hornwort samples. There are indications that the more abundant the cyanobacteria, the less likely are hornworts to harbour fungi. Thus, Nostoc cyanobacteria are most extensive in the thallus channels of fungus-free Leiosporoceros [15], and cyanobacterial chambers are most prominent in P. hirticalyx (J. G. Duckett & S. Pressel 2012, unpublished data), which frequently lacks a fungus. In Blasiales, the only liverworts with cyanobacteria, Nostoc are more numerous than in hornworts, and fungi are absent [46]. As in liverworts, hornwort sporophytes are fungus-free, and hyphae never occur in the placental region despite its extensive mucilage-filled intercellular spaces [47].

How the newly discovered intimate symbioses, or lack thereof, between hornworts and fungi from Glomeromycota and/or Mucoromycotina facilitate or constrain establishment and growth under different environmental conditions is unknown. Sources of uncertainty include (i) the evolutionary relationships and ecological niche of Mucoromycotina, a group of fungi where taxon sampling remains severely limited but which it is becoming increasingly clear harbours extensive phylogenetic diversity and was instrumental in the origin and diversification of land plants; (ii) that the fungi of only a few ferns, lycopods and liverworts are known; (iii) that some early branching events during terrestrial plant evolution are poorly supported by current analyses; and (iv) that the functional significance of the symbioses is untested. Here, we opened new windows into the history of plants and fungi in terrestrial ecosystems, and the current distribution and ecology of plant–fungal symbioses.

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Trappe, P. McGee, C. Walker and Oregon State University Herbarium for fungal specimens, Z. Ludlinska (Nanovision Centre, Queen Mary University of London) for her invaluable assistance in operating the cryo-SEM, DoC New Zealand and Fairy Lake Botanical Garden, China, for collecting permits, C. Walker for comments on the manuscript, and W. Rimington for help generating molecular data. A.D. was funded by the University of Turin and Bando ad Alta Formazione of the Regione Piemonte. J.G.D. thanks the Leverhulme Trust for an Emeritus Fellowship that enabled this study. J.C.V. was supported by DFG grant no. RE-603/14-1.

References

- 1.Groth-Malonek M, Pruchner D, Grewe F, Knoop V. 2004. Ancestors of trans-splicing mitochondrial introns support serial sister relationships of hornworts and mosses with vascular plants. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 117–125 10.1093/molbev/msh259 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msh259) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qiu Y-L, et al. 2006. The deepest divergences in land plants inferred from phylogenomic evidence. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 15 511–15 516 10.1073/pnas.0603335103 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0603335103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renzaglia KS, Villarreal JC, Duff RJ. 2009. New insights into morphology, anatomy, and systematics of hornworts. In Bryophyte biology (eds Goffinet B, Shaw AJ.), pp. 139–172, 2nd. edn. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wikström N, He-Nygrén X, Shaw AJ. 2009. Liverworts (Marchantiophyta). In The time tree of life (eds Hedges SB, Kumar S.), pp. 146–152 New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang Y, Graham SW. 2011. Inferring the higher-order phylogeny of mosses (Bryophyta) and relatives using a large, multigene plastid data set. Am. J. Bot. 98, 839–849 10.3732/ajb.0900384 (doi:10.3732/ajb.0900384) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villarreal JC, Renner SS. 2012. Hornwort pyrenoids: carbon-concentrating mechanisms evolved and were lost at least five times during the last 100 million years. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 18 873–18 878 10.1073/pnas.1213498109 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1213498109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villarreal JC, Cargill DC, Hagborg A, Söderström L, Renzaglia KS. 2010. A synthesis of hornwort diversity: patterns, causes and future work. Phytotaxa 9, 150–166 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schüßler A, Schwarzott D, Walker C. 2001. A new fungal phylum, the Glomeromycota: phylogeny and evolution. Mycol. Res. 105, 1413–1421 10.1017/S0953756201005196 (doi:10.1017/S0953756201005196) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang B, Qiu Y-L. 2006. Phylogenetic distribution and evolution of mycorrhizas in land plants. Mycorrhiza 16, 299–363 10.1007/s00572-005-0033-6 (doi:10.1007/s00572-005-0033-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith VSE, Read DJ. 2008. Mycorrhizal symbiosis, 3rd edn San Diego, CA: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bidartondo MI, Read DJ, Trappe JM, Merckx V, Ligrone R, Duckett JG. 2011. The dawn of symbiosis between plants and fungi. Biol. Lett. 7, 574–577 10.1098/rsbl.2010.1203 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2010.1203) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ligrone R. 1988. Ultrastructure of a fungal endophyte in Phaeoceros laevis (L.) Prosc. (Anthocerophyta). Bot. Gaz. 149, 92–100 10.1086/337695 (doi:10.1086/337695) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schüßler A. 2000. Glomus claroideum forms an arbuscular mycorrhiza-like symbiosis with the hornwort Anthoceros punctatus. Mycorrhiza 10, 15–21 10.1007/s005720050282 (doi:10.1007/s005720050282) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pocock K, Duckett JG. 1984. A comparative ultrastructural analysis of the fungal endophytes in Cryptothallus mirabilis Malm. and other British thalloid hepatics. J. Bryol. 13, 227–233 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Villarreal JC, Renzaglia KS. 2006. Structure and development of Nostoc strands in Leiosporoceros dussii (Anthocerotophyta): a novel symbiosis in land plants. Am. J. Bot. 93, 693–705 10.3732/ajb.93.5.693 (doi:10.3732/ajb.93.5.693) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerdemann JW, Trappe JM. 1974. The Endogonaceae in the Pacific Northwest. Mycol. Mem. 5, 1–76 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ligrone R, Duckett JG. 1994. Cytoplasmic polarity and endoplasmic microtubules associated with the nucleus and organelles are ubiquitous features of food-conducting cells in bryoid mosses (Bryophyta). New Phytol. 127, 601–614 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb03979.x (doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb03979.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duckett JG, Pressel S, P'ng KMY, Renzaglia KS. 2009. Exploding a myth: the capsule dehiscence mechanism and the function of pseudostomata in Sphagnum. New Phytol. 183, 1053–1063 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02905.x (doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02905.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardes M, Bruns TD. 1993. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes - application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 2, 113–118 10.1111/j.1365-294X.1993.tb00005.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.1993.tb00005.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor JW. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR protocols (eds Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, White TJ.), pp. 315–322 San Diego, CA: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smit E, Leeflang P, Glandorf B, Van Elsas JD, Wernars K. 1999. Analysis of fungal diversity in the wheat rhizosphere by sequencing of cloned PCR-amplified genes encoding 18S rRNA and temperature gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 2614–2621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee J, Lee S, Young JPW. 2008. Improved PCR primers for the detection and identification of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 65, 339–349 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00531.x (doi:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00531.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall TA. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739 10.1093/molbev/msr121 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msr121) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinformatics 5, 113. 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113 (doi:10.1186/1471-2105-5-113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Löytynoja A, Goldman N. 2010. webPRANK: a phylogeny-aware multiple sequence aligner with interactive alignment browser. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 579. 10.1186/1471-2105-11-579 (doi:10.1186/1471-2105-11-579) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389 (doi:10.1093/nar/25.17.3389) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Wheeler DL. 2008. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D25–D30 10.1093/nar/gkm929 (doi:10.1093/nar/gkm929) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silvestro D, Michalak I. 2012. RaxmlGUI: a graphical front-end for RAxML. Org. Divers. Evol. 12, 335–337 10.1007/s13127-011-0056-0 (doi:10.1007/s13127-011-0056-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. 2003. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. 2008. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat. Methods 9, 772. 10.1038/nmeth.2109 (doi:10.1038/nmeth.2109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piel WH, Donoghue MJ, Sanderson MJ. 2002. TreeBASE: a database of phylogenetic knowledge. In To the interoperable ‘catalog of life’ with partners species 2000 Asia Oceania (eds Shimura J, Wilson KL, Gordon D.), pp. 41–47 Research Report no. 171. Tsukuba, Japan: National Institute for Environmental Studies [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duff RJ, Cargill DC, Villarreal JC, Renzaglia KS. 2004. Phylogenetic relationships of the hornworts based on rbcL sequence data: novel relationships and new insights. In Molecular systematics of bryophytes 98 (eds Goffinet B, Hollowell V, Magill R.), pp. 41–58 St Louis, MO: Missouri Botanical Garden Press [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duff RJ, Villarreal JC, Cargill DC, Renzaglia KS. 2007. Progress and challenges in hornwort phylogenetic reconstruction. Bryologist 110, 214–243 10.1639/0007-2745(2007)110[214:PACTDA] (doi:10.1639/0007-2745(2007)110[214:PACTDA]) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. 2008. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web-servers. Syst. Biol. 75, 758–771 10.1080/10635150802429642 (doi:10.1080/10635150802429642) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maddison WP, Maddison DR. 2011. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 2.75. See http://mesquiteproject.org. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krüger M, Krüger C, Walker C, Stockinger H, Schüßler A. 2012. Phylogenetic reference data for systematics and phylotaxonomy of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi from phylum to species level. New Phytol. 193, 970–984 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03962.x (doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03962.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bidartondo MI, Duckett JG. 2010. Conservative ecological and evolutionary patterns in liverwort–fungal symbioses. Proc. R. Soc. B 277, 485–492 10.1098/rspb.2009.1458 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.1458) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trappe JM. 1987. Phylogenetic and ecologic aspects of mycotrophy in the angiosperms from an evolutionary standpoint. In Ecophysiology of VA mycorrhizal plants (ed. Safir GR.), pp. 5–25 Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duckett JG, Carafa A, Ligrone RA. 2006. Highly differentiated glomeromycotean association with the mucilage-secreting, primitive antipodean liverwort Treubia: clues to the origins of mycorrhizas. Am. J. Bot. 93, 797–813 10.3732/ajb.93.6.797 (doi:10.3732/ajb.93.6.797) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pressel S, Bidartondo MI, Ligrone R, Duckett JG. 2010. Fungal symbioses in bryophytes: new insights into the twenty first century. Phytotaxa 9, 238–253 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krings M, Taylor TN, Hass H, Kerp H, Dotzler N, Hermsen EJ. 2007. Fungal endophytes in a 400-million-yr-old land plant: infection pathways, spatial distribution, and host responses. New Phytol. 174, 648–657 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02008.x (doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02008.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krings M, Taylor TN, Hass H, Kerp H, Dotzler N, Hermsen EJ. 2007. An alternative mode of early land plant colonization by putative endomycorrhizal fungi. Plant Signal. Behav. 2, 125–126 10.4161/psb.2.2.3970 (doi:10.4161/psb.2.2.3970) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonfante-Fasolo P, Scannerini S. 1976. The ultrastructure of the zygospore in Endogone flammicorona Trappe & Gerdemann. Mycopathologia 59, 117–123 10.1007/BF00493564 (doi:10.1007/BF00493564) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schüßler A, Martin H, Cohen D, Fitz M, Wipf D. 2007. Arbuscular mycorrhiza: studies on the Geosiphon symbiosis lead to the characterization of the first glomeromycotean sugar transporter. Plant Signal. Behav. 2, 431–434 10.4161/psb.2.5.4465 (doi:10.4161/psb.2.5.4465) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duckett JG, Prasad AKSK, Davies DA, Walker S. 1977. A cytological analysis of the Nostoc–bryophyte relationship. New Phytol. 79, 349–362 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1977.tb02215.x (doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1977.tb02215.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ligrone R, Duckett JG, Renzaglia KS. 1993. The gametophyte–sporophyte junction in land plants. Adv. Bot. Res. 19, 231–317 10.1016/S0065-2296(08)60206-2 (doi:10.1016/S0065-2296(08)60206-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]