Abstract

The discovery of the key role of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in initiating innate immune responses and modulating adaptive immunity has revolutionized our understanding of vertebrate defence against pathogens. Yet, despite their central role in pathogen recognition and defence initiation, there is little information on how variation in TLRs influences disease susceptibility in natural populations. Here, we assessed the extent of naturally occurring polymorphisms at TLR2 in wild bank voles (Myodes glareolus) and tested for associations between TLR2 variants and infection with Borrelia afzelii, a common tick-transmitted pathogen in rodents and one of the causative agents of human Lyme disease. Bank voles in our population had 15 different TLR2 haplotypes (10 different haplotypes at the amino acid level), which grouped in three well-separated clusters. In a large-scale capture–mark–recapture study, we show that voles carrying TLR2 haplotypes of one particular cluster (TLR2c2) were almost three times less likely to be Borrelia infected than animals carrying other haplotypes. Moreover, neutrality tests suggested that TLR2 has been under positive selection. This is, to our knowledge, the first demonstration of an association between TLR polymorphism and parasitism in wildlife, and a striking example that genetic variation at innate immune receptors can have a large impact on host resistance.

Keywords: wildlife disease, host–parasite interactions, Borrelia, innate immune defence, Toll-like receptors, disease resistance

1. Introduction

Parasites, by definition, are harmful to their hosts and should therefore impose selection for enhanced resistance. Despite this, there is typically significant genetic variation for resistance to parasites and pathogens in natural populations [1]. To elucidate the evolutionary causes and consequences of such variation, a better understanding of which genes actually contribute to variation in resistance is desirable [2–4]. However, whereas there is a considerable body of literature on the genetic basis of resistance in humans [5], knowledge from other animals, and in particular from natural vertebrate populations, is as yet very limited (but see [6]).

The principal weapon that hosts have evolved to fight off pathogens is the immune system, which in vertebrates consists of two main parts, innate and acquired immunity [7]. Invading infectious agents are initially recognized by the innate branch of the immune system through pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs). PRRs recognize structures that are specific to microbes (microbe- or pathogen-associated molecular patterns). After stimulation by the ligand, PRRs activate an intracellular signalling cascade, which initiates innate and acquired immune responses [8–10]. An important class of PRRs are Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which were discovered in vertebrates as late as 1997 [11]. Most mammals have 10–13 different TLRs, each recognizing different ligands [12]. TLRs have been found to play a key role in pathogen recognition and initiation of immune responses in humans and laboratory animals [13,14], and there is an increasing number of studies in humans showing associations between TLR polymorphisms and infectious diseases [14–16]. Yet, TLR polymorphisms have, unlike polymorphisms at the major histocompatibility complex [17], thus far received little attention from ecologists investigating host–parasite interactions and wildlife disease (but see, e.g. [6,18,19]).

Here, we investigated the role of naturally occurring TLR2 polymorphisms in mediating parasite resistance (here defined as the ability to prevent and/or clear infection, and measured as the presence/absence of infection) in a population of wild-living bank voles (Myodes glareolus) by testing for associations between TLR2 genotype and Borrelia afzelii infection status. Borrelia afzelii is a common tick-transmitted pathogen in rodents [20], and one of the causative agents of human Lyme borreliosis in Europe [21,22]. Lipopeptides, which are central components of the cell walls of Borrelia, are ligands for TLR2, and knock-out studies with laboratory mice have shown that TLR2 plays an important role in the recognition and the initiation of immune responses against Borrelia [23–27]. Moreover, there is evidence that a common single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in the human TLR2 affects susceptibility to Lyme disease [28]. By transferring this immunological background knowledge into an ecological context, we here show that polymorphisms at TLR2 are associated with B. afzelii infection in a natural rodent population, highlighting the important role of TLRs in mediating disease susceptibility in wildlife.

2. Material and methods

(a). Study species

The bank vole (M. glareolus, Rodentia) is one of the main hosts of B. afzelii in Europe. Borrelia afzelii is transmitted by the sheep tick (Ixodes ricinus) between hosts [29]. We captured bank voles in 2008 in Kalvs Mosse (N 55° 42.470′, E 13° 29.216′), a homogeneous, deciduous woodland of about 0.25 km2 southeast of Revingeby, Skåne, Southern Sweden using live-traps (Ugglan Special No1, Grahnab, Gnosjö, Sweden). Animals were caught during trapping sessions in May (n = 31; 100% adults), June (n = 171; 45% adults), August (n = 252; 43% adults), September (n = 320; 29% adults) and October (n = 350; 29% adults). They were weighed (±0.1 g), and the number of tick larvae on the ears was counted as a proxy for infestation with nymphs, the main infective stage [30]. Molecular sexing was performed by amplifying a fragment of the male-specific sex-determining region Y as described in Wandeler et al. [31]. At first capture, animals were individually marked with subcutaneous transponder tags (Trovan ID-100B, AEG ID, Ulm, Germany) to allow for the identification of individuals upon recapture. We obtained ear biopsies from 726 individuals during the trapping sessions. Samples were stored in 70 per cent ethanol for later DNA extraction (as described in [19,32]), TLR2 genotyping and determination of Borrelia infection status. All animal procedures were performed under licences M101-06 and M141-10 issued by the Malmö/Lund, Sweden ethical board for animal experiments.

(b). Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) genotyping

Mammals have a single functional copy of TLR2 [12]. There is a TLR2 pseudogene in humans and dogs, but not in mice [12]. In bank voles, the entire TLR2 coding region is 2352 bp long [19]. For this study, we sequenced a 1173 bp long fragment of TLR2 from bp 691 to 1863 as described in Tschirren et al. [33]. There was no indication that we amplified more than one locus (at most two peaks per site in the chromatograms), and we found no sign of pseudogenes (no stop codons or frame shift mutations). The sequenced part of TLR2 contains most of the functionally relevant sites involved in pathogen–recognition and TLR2–TLR1 heterodimerization [34,35], and we previously demonstrated molecular signatures of positive selection during the evolutionary history of rodents [19], as well as strong population differentiation and isolation by distance across bank vole populations within this gene region [33]. The amplicon consisted of coding sequence only. Sequences were processed, assembled and aligned using Geneious v. 5.0.4. [36], and all polymorphisms were examined by eye. TLR2 haplotypes were reconstructed with PHASE v. 2.1 [37,38] using the default settings of a thinning interval of one, 100 burn-in iterations and 100 main iterations. Haplotypes were submitted to NCBI GenBank (see table 1 for accession nos).

Table 1.

TLR2 haplotype frequencies. Bank vole TLR2 haplotype frequencies, haplotype cluster and GenBank accession no. n = 1452 haplotypes.

To test whether patterns of haplotype frequencies and tree topology are consistent with neutral expectations, we performed two neutrality tests: Fay & Wu's H [39] and Li's maximum frequency of derived mutations (MFDM) [40]. For the former, the empirical distribution of the test statistics was generated using neutral coalescent simulations in DNAsp [41], based on the observed number of segregating sites, 20 000 replicates and the assumption of no recombination (no recombination was detected with the MFDM test). The results of this analysis did not change qualitatively when allowing for moderate levels of recombination (data not shown). For both tests, we used the Mus musculus (NM_011905.3), Apodemus flavicollis (JN674549.1) and Myodes rufocanus (HM215593.1) TLR2 sequences as outgroups. Deviation from neutrality detected by Fay & Wu's H can be caused by selection and/or demographic processes such as population expansion or bottlenecks [40,42]. Li's MFDM is robust against population size changes, but can be sensitive to admixture events [40].

To identify clusters of host haplotypes we constructed a TLR2 haplotype network in TCS 1.21 [43]. Homology models for the most common haplotype of each cluster (haplotype 1 and 6, see §3) were generated based on the human TLR1–TLR2 lipopetide crystal structure [35]. Alignments were generated with ClustalW [44], manually curated where necessary, and served as the input for program Modeler 9 v. 4 [45]. Figures were prepared using PyMol (http://www.pymol.org/).

(c). Borrelia infection status

To determine whether voles were infected with B. afzelii, we performed flaB real-time PCR assays as described in Råberg [46] (n = 1124 samples). Samples with a melting temperature between 78.15°C and 78.75°C and a Ct value corresponding to greater than or equal to 1 B. afzelii spirochaete were considered positive. The PCR assay is specific for B. afzelii [46].

Borrelia afzelii is the only Lyme borreliosis-causing Borrelia species observed in our bank vole population. The relapsing fever-causing Borrelia species, B. miyamotoi is also found, although at very low prevalence [46].

Whereas B. afzelii infection status is highly repeatable (once infected, an individual stays infected for life [47]), we found that an individual's infection intensity (number of B. afzelii spirochaetes per unit host tissue) varied considerably over time. Therefore, we focused on infection status only.

(d). Statistical analyses

The reconstructed TLR2 haplotype network revealed that TLR2 haplotypes grouped in three clearly separated clusters, one of which was very rare (see §3). To increase the statistical power to detect differences in B. afzelii infection among individuals with functionally different TLR2, we focused on the two common clusters and determined for each individual bank vole if it carried two TLR2 haplotypes belonging to the first cluster (TLR2c1), two haplotypes belonging to the second cluster (TLR2c2), or one haplotype of each cluster (see figure 1 and electronic supplementary material, S1). This approach is very powerful, yet conservative because it assumes that haplotypes within clusters are functionally identical. We used a generalized linear mixed model with a binomial error structure to test for differences in B. afzelii infection between host TLR2 clusters. We included number of haplotypes belonging to cluster TLR2c2 (zero, one or two), host age class (adult, more than 20 g; subadult, 15–20 g; juvenile, less than 15 g; [48]), sex and their two-way interactions as fixed effects in the statistical model. Individual identification (ID) and trapping session (month) were included as random effects to account for the non-independence of measures from an individual captured during more than one trapping session and for seasonal variation in Borrelia prevalence.

Figure 1.

TLR2 haplotype network. Reconstructed bank vole TLR2 haplotype network based on 726 individuals. Circle sizes reflect the number of haplotype copies found in the population. The circle size for 50, 150 and 350 copies is given as a reference. The numbers along the connecting lines indicate the positions of the (synonymous and non-synonymous) substitutions that separate different haplotypes. Different colours (and numbers) indicate that haplotypes differ at the amino acid level. Haplotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 14 grouped into one major haplotype cluster (TLR2c1; green), haplotypes 6, 7, 8, 9 grouped into a second major haplotype cluster (TLR2c2; red). Haplotype 10 formed a third group.

Because differences in B. afzelii infection among individuals could be owing to differences in resistance or exposure, we ran the same model, but with a Poisson error structure, to test for differences in tick load (i.e. the Borrelia vector) between TLR2 clusters. We used number of larvae as a proxy for exposure to nymphs (the main infective stage), because nymphs are comparably rare and therefore difficult to quantify accurately [30].

Analyses were run in R v. 2.14.1 [49] using the glmer function, part of the lme4 package [50]. For all analyses, the significance of the fixed effects was determined by comparing two nested models, with and without the factor of interest, using likelihood-ratio tests.

In addition, we also used a model selection procedure using Akaike information criterion with a correction for finite sample sizes (AICc) to determine which model best explains variation in Borrelia infection status. Candidate models contained combinations of TLR2 genotype, age class and sex. All candidate models contained individual ID and trapping session as random effects. Model selection was performed using the MuMIn package in R v. 2.14.1 [49].

3. Results

(a). TLR2 diversity in wild-living bank voles

TLR2 diversity was high in the surveyed bank vole population with 15 unique DNA haplotypes, of which 10 differed at the amino acid sequence. The most common amino acid haplotype (haplotype 1) occurred in six variants (1a–f), which differed at the nucleotide, but not the amino acid level (i.e. only synonymous substitutions). No synonymous variants were observed in the other nine haplotypes. The frequencies of the different TLR2 haplotypes are shown in table 1 (n = 726 individuals).

Both neutrality tests indicated that positive selection has shaped TLR2. Fay & Wu's test detected an excess of high-frequency derived haplotypes in the population (Mus musculus as outgroup: H = −14.95, p < 0.001; Apodemus falvicollis as outgroup: H = −15.21, p = 0.012; Myodes rufocanus as outgroup: H = −13.27, p = 0.023). Similarly, Li's MFDM test, which uses tree topology to infer selection, was significant (p < 0.009).

A reconstructed haplotype network revealed two major TLR2 clusters (TLR2c1 and TLR2c2; figure 1). The main difference between the two clusters were six linked, non-synonymous SNPs spread out over a region of 290 amino acids (in leucine-rich repeat (LRR) 10—C-terminal LRR domain; [35], electronic supplementary material, S1). Cluster TLR2c1 consisted of haplotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 14 (63.3% overall frequency) and was defined by the six-site amino acid combination ‘276Thr/417Asp/453Met/484Ile/536Val/565Asn’, whereas cluster TLR2c2 consisted of haplotypes 6, 7, 8, 9 (33.4% overall frequency; figure 1) and was defined by the alternative amino acid combination ‘276Ala/417Gly/453Thr/484Leu/536Ile/565Asp’. One rare haplotype (10, frequency 3.3%; figure 1) did not group with either of the two major clusters, but formed a third, well-separated group (figure 1). We did not consider this third cluster in the analyses because of its low frequency. Because the six high-frequency SNPs that separated the two major haplotype clusters always co-occurred (i.e. were perfectly linked), we tested for associations between Borrelia infection and TLR2 clusters rather than individual SNPs in the subsequent analyses. TLR2 SNPs that separated haplotypes within clusters were not considered in the analysis because they were relatively rare (table 1; frequency of homozygotes less than 3%) and statistical power to detect associations between Borrelia infection and these SNPs was therefore low.

(b). Structural differences between TLR2 haplotypes

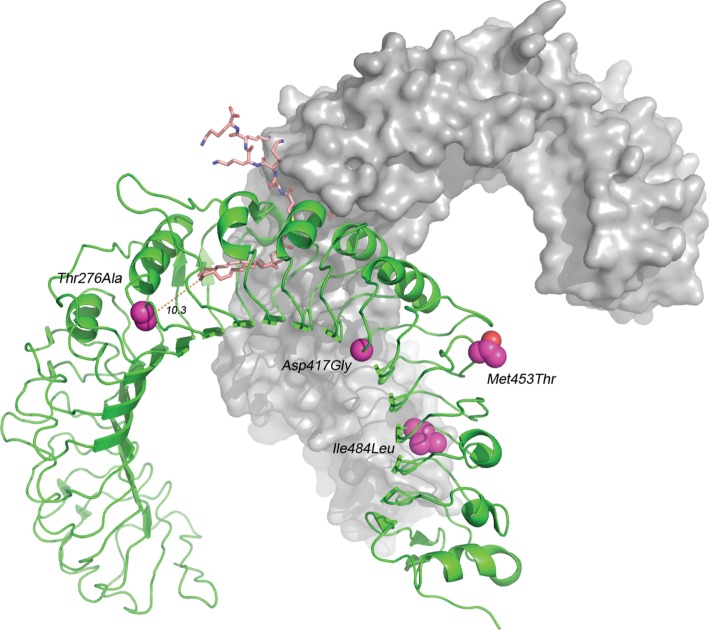

To investigate whether any of the six linked SNPs that separated the two major haplotype clusters could potentially affect ligand binding, we modelled the structure of the bank vole TLR2. Based on the human TLR2–TLR1 lipopeptide crystal structure [35], we generated homology models for the most common TLR2 haplotype of each cluster, haplotype 1 and 6. These models confirmed a high degree of structural conservation between the human and bank vole TLR2–TLR1 complex (55% sequence identity for TLR2 residues 206–549). Furthermore, all residues that are involved in the TLR1–TLR2 interface are conserved between humans and bank voles, suggesting that human and bank vole TLR2 possess similar modes of action. None of the polymorphic sites are located directly in the TLR1–TLR2 interface, but the polymorphic site at amino acid position 276 in LRR 10 (see the electronic supplementary material, S1) is likely to have a significant impact on ligand binding. The side chain of the amino acid at position 276 is pointing into the hydrophobic core of the TLR2–TLR1 complex and is located in close proximity (10.3 Å) to the putative binding site for the Borrelia lipopeptide (figure 2). The amino acids found at this position (276Ile in humans) in the two haplotype clusters (276Thr versus 276Ala) differ markedly in size and polarity, which, given their location, is likely to affect the size of the hydrophobic pocket, and thereby ligand binding. The polymorphic sites 417, 453 and 484 in the TLR2–TLR1 complex are located more than 18 Å away from the ligand-binding site, and the side chains of residues at positions 417 and 453 are pointing towards the solvent, which makes it unlikely that they influence ligand-binding directly. However, they could still affect the thermodynamic stability of TLR2. Polymorphic sites 536 and 565 were outside the template structure (human TLR2–TLR1 complex; [35]) and could not be modelled. However, because of their location in LRR 20 and the C-terminal domain, we would not expect a prominent effect of these amino acid mutations on ligand affinity [35].

Figure 2.

Bank vole TLR2–TLR1 complex. Homology-based structural model of the bank vole TLR2–TLR1 complex showing four amino acid mutations that characterize haplotypes of cluster TLR2c1 and TLR2c2, respectively. Polymorphic site 276 is located 10.3 Å from the ligand. Amino acid mutations 536 and 565 were outside the template structure and are not shown. Pink bubbles, polymorphic sites; green, TLR2; grey, TLR1; dusky pink, ligand.

(c). TLR2 polymorphisms are associated with Borrelia infection status

Overall prevalence of B. afzelii infection reached 34.1 per cent in adult bank voles (more than 20 g), but was markedly lower in subadults (15–20 g; 10% infected) and juveniles (less than 15 g; 5.6% infected; χ22 = 99.38, p < 0.001). Similar results were obtained when analysing differences in Borrelia prevalence across age classes for each trapping session separately (see the electronic supplementary material, S2). The low Borrelia prevalence in juveniles and subadults is probably owing to limited Borrelia exposure rather than higher resistance. Indeed, subadults and juveniles were infested with more than four-times fewer ticks than adult voles (χ22 = 92.67, p < 0.001). Again, similar results were obtained when analysing differences in tick load across age classes for each trapping session separately (see the electronic supplementary material, S3). Because of differential Borrelia exposure, associations between genetic determinants of resistance and Borrelia prevalence are predicted to be pronounced in adults, but much weaker, or absent, in juveniles and subadults. In line with this prediction, there was a significant interaction effect between age class and TLR2 genotype on Borrelia infection status (χ24 = 10.26, p = 0.036). No significant association between TLR2 clusters and Borrelia infection was observed in juveniles (χ22 = 2.55, p = 0.279) or subadults (χ22 = 0.24, p = 0.886). Adult bank voles, however, differed significantly in Borrelia infection status depending on their TLR2 genotype (χ22 = 12.27, p = 0.002; figure 3). Borrelia prevalence was lowest in adult voles carrying two haplotypes belonging to cluster TLR2c2 and highest in individuals carrying two haplotypes belonging to cluster TLR2c1. Voles with one haplotype of each cluster had intermediate infection prevalence (figure 3). A posteriori tests revealed that individuals carrying one haplotype of each cluster were significantly less likely to be Borrelia infected than individuals with two haplotypes of cluster TLR2c1 (χ22 = 5.99, p = 0.014). However, they were not significantly different from individuals with two haplotypes of cluster TLR2c2 (χ22 = 2.39, p = 0.122), probably owing to a large confidence interval (CI) in this latter group (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Genetic polymorphisms at TLR2 are associated with Borrelia infection status. Prevalence of Borrelia infection in adult bank voles (n = 234) with two haplotypes belonging to cluster TLR2c1 (c1/c1), two haplotypes belonging to cluster TLR2c2 (c2/c2), or one haplotype of each cluster (c1/c2). Mean proportions ±95% CIs are shown.

Males were more likely to be Borrelia infected than females (χ22 = 4.51, p = 0.034), but the association between TLR2 clusters and Borrelia infection did not differ significantly between the sexes (χ22 = 3.73, p = 0.155). There was no significant difference in tick load between TLR2 clusters (χ22 = 2.43, p = 0.296). Including tick load as a covariate in the model of Borrelia prevalence (see above) did not change the significant association between TLR2 clusters and Borrelia infection (χ22 = 7.44, p = 0.024).

A model selection procedure based on AICc values largely confirmed these results (except for the sex differences in infection) and revealed that a model containing TLR2 genotype, age class and the interaction between TLR2 genotype and age class best explained variation in Borrelia infection status of voles. All other candidate models had a ΔAICc > 2. Model averaging revealed a significant effect of TLR2 genotype, with individuals with a TLR2c1/TLR2c2 (95% CI: −3.57 to −0.33) and a TLR2c2/TLR2c2 (95% CI: −6.46 to −0.29) genotype being significantly less likely to be Borrelia infected. Furthermore, juveniles (95% CI: −6.67 to −1.22) and subadults (95% CI: −4.44 to −1.82) were significantly less likely to be Borrelia infected.

4. Discussion

Using a candidate gene approach, we have shown that polymorphisms at the innate immune receptor TLR2 are associated with B. afzelii infection status in a natural rodent population. Genetic diversity at TLR2 was high in the studied bank voles, and a reconstructed haplotype network revealed that TLR2 variants grouped in well-defined clusters. The same clusters were also found in other bank vole populations in southern Sweden (0.3–342 km apart) [33], indicating that this unusual haplotype network is not specific to our study population.

Homology modelling based on the human TLR2–TLR1 complex indicated that the polymorphism at position 276 (Thr276Ala), which was one of the six linked non-synonymous mutations that defined the two major haplotype clusters, may have pronounced functional consequences for ligand binding of the TLR2–TLR1 complex [35]. Consistent with the hypothesis that Thr276Ala, or linked amino acid mutations, affect the function of the TLR2–TLR1 complex, we observed marked differences in Borrelia prevalence in adult voles with different TLR2 genotypes. Animals with two haplotypes belonging to cluster TLR2c2 were almost three times less likely to be Borrelia infected compared with animals with two haplotypes belonging to cluster TLR2c1. Whereas there were clear differences in Borrelia infection status, we found no difference in tick load between TLR2 haplotype clusters, suggesting that TLR2 genotype influences the hosts' resistance to B. afzelii rather than their rate of exposure (e.g. through indirect effects of TLR2 genotype on host behaviour). Adult males were more heavily infected with B. afzelii than adult females. This might be owing to a higher moving activity of males, which influences Borrelia encounter [51], and/or higher testosterone levels, which negatively influences parasite control [52]. Despite these behavioural and physiological differences, the relationship between TLR2 genotype and B. afzelii infection was similar in the two sexes. Furthermore, the association between TLR2 clusters and B. afzelii infection was pronounced in adults after dispersal, but absent in juveniles before dispersal [53], indicating that the observed pattern is unlikely to be owing to non-genetic factors shared by family members (i.e. B. afzelii abundance in a territory). The conclusion that there is a causal relationship between TLR2 polymorphisms and the voles' resistance to B. afzelii is in line with the results of knock-out studies in laboratory mice, which have identified TLR2 as a candidate gene for Borrelia resistance [23–27]. Nevertheless, given the correlative nature of our study, we cannot exclude the possibility that a linked locus, rather than TLR2 itself, is driving the observed relationship.

What immunological mechanisms could mediate an association between TLR2 polymorphisms and B. afzelii infection status? In principle, improved resistance could be a result of enhanced innate or acquired immune responses. Infections with B. afzelii and other Lyme borreliosis spirochaetes typically result in chronic infections in their natural hosts, with low rates of clearance once the infection has established and disseminated [47]. This suggests that the improved resistance conferred by variants of cluster TLR2c2 acts via mechanisms expressed early during infection, that is, effectors belonging to the innate immune system. Recent studies have shown that TLRs can activate the complement system [54], a component of innate immunity known to be important for resistance against Borrelia [55]. Thus, one possibility is that a higher affinity of cluster TLR2c2 haplotypes to B. afzelii ligands results in a stronger complement response.

Haplotype 6 was the most common TLR2 haplotype in the host population, but unlike the common haplotype of cluster TLR2c1(haplotype 1), which occurred in six variants, this haplotype has not yet accumulated any synonymous nucleotide substitutions. Synonymous nucleotide substitutions are considered to be selectively neutral (but see [56,57]), and to accumulate over time at a gene specific point-mutation rate [58]. The complete lack of synonymous nucleotide substitutions in haplotype 6, despite its high frequency, is consistent with recent positive selection that has favoured this haplotype. This is also reflected by significant Fay & Wu's H and Li's MFDM tests, which both indicate that positive selection has acted on TLR2 [40,59]. Although the latter test is comparably robust against demographic processes [40], it is important to acknowledge that it is difficult to fully disentangle selection and demography with the currently available data. Nevertheless, the structure of the haplotype network and the results of the neutrality tests in combination with the finding that animals carrying haplotype 6 had lower B. afzelii prevalence suggests that this TLR2 variant may have increased in frequency as a result of parasite-mediated selection (by Borrelia or other pathogens).

While our results are in line with the hypothesis that parasite-mediated selection has shaped TLR2 evolution in bank voles, it is as yet difficult to assess the role of B. afzelii as a selective agent because very little is known about the fitness-consequences of Borrelia infection in natural populations. In white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus), experimental infection with B. burgdorferi sensu stricto in the laboratory led to carditis and multifocal arthritis [60], which probably affects host survival and/or reproduction in the wild. However, the two (correlative) studies performed in wild-living hosts to date, one in white-footed mice [61] and one in black-legged kittiwakes (Rissa tridactyla) [62], did not find indication for survival costs of Borrelia infection. Yet, the strength of selection required to drive a selective sweep is relatively low. For example, Obbard et al. [63] estimated that the selective advantage driving the evolution of Ago2, one of the fastest evolving immune genes in Drosophila, was a mere 0.5–1%. Clearly, it would be very difficult to detect such low levels of selection in a field study.

In conclusion, our study shows that polymorphism at TLR2 is associated with Borrelia infection in wild bank voles, one of the main reservoir hosts of B. afzelii in Europe. This is, to our knowledge, the first demonstration of an association between TLR polymorphism and parasitism in a natural, non-human population. Together with our previous finding that patterns of TLR2 diversity and population differentiation in bank voles are consistent with local adaptation processes [33], our results highlight the important, but often neglected [64], role of the innate branch of the vertebrate immune system in mediating resistance to pathogens in wildlife. The recent characterization of TLRs in a range of non-model organisms [19,65] makes these genes suitable candidates for future research on the molecular ecology of resistance to parasites.

Acknowledgements

All animal procedures were performed under licences M101-06 and M141-10 issued by the Malmö/Lund, Sweden ethical board for animal experiments.

We thank Staffan Bensch, Jenny Morger and Erik Postma for discussion and two anonymous reviewers for comments on the manuscript. This work was funded by the Swedish Research Council (grant nos 621-2206-2876 and 621-2006-4551 to L.R. and H.W.), the Crafoord Foundation (grant no. 20060662 to L.R.) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant nos PA0033_121466 and PP00P3_128386 to B.T.).

References

- 1.Lazzaro BP, Little TJ. 2009. Immunity in a variable world. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 15–26 10.1098/rstb.2008.0141 (doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0141). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siva-Jothy MT, Skarstein F. 1998. Towards a functional understanding of 'good genes’. Ecol. Lett. 1, 178–185 10.1046/j.1461-0248.1998.00033.x (doi:10.1046/j.1461-0248.1998.00033.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolhouse MEJ, Webster JP, Domingo E, Charlesworth B, Levin BR. 2002. Biological and biomedical implications of the co-evolution of pathogens and their hosts. Nat. Genet. 32, 569–577 10.1038/ng1202-569 (doi:10.1038/ng1202-569) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen DE, Little TJ. 2009. Exploring the molecular landscape of host–parasite coevolution. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 74, 169–176 10.1101/sqb.2009.74.022 (doi:10.1101/sqb.2009.74.022) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaslow RA, McNicholl J, Hill AVS. 2008. Genetic susceptibility to infectious diseases. New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner AK, Begon M, Jackson JA, Bradley JE, Paterson S. 2011. Genetic diversity in cytokines associated with immune variation and resistance to multiple pathogens in a natural rodent population. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002343. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002343 (doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002343) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy K, Travers P, Walport M. 2008. Janeway‘s immunobiology, 7th edn. New York, NY: Garland Science [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeda K, Kaisho T, Akira S. 2003. Toll-like receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21, 335–376 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126 (doi:10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141126) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. 2006. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell 124, 783–801 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akira S, Takeda K. 2004. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 499–511 10.1038/nri1391 (doi:10.1038/nri1391) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Janeway CA. 1997. A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature 388, 394–397 10.1038/41131 (doi:10.1038/41131) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roach JC, Glusman G, Rowen L, Kaur A, Purcell MK, Smith KD, Hood LE, Aderem A. 2005. The evolution of vertebrate Toll-like receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 9577–9582 10.1073/pnas.0502272102 (doi:10.1073/pnas.0502272102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medzhitov R. 2001. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 1, 135–145 10.1038/35100529 (doi:10.1038/35100529) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Netea MG, Wijmenga C, O'Neill LAJ. 2012. Genetic variation in Toll-like receptors and disease susceptibility. Nat. Immunol. 13, 535–542 10.1038/ni.2284 (doi:10.1038/ni.2284) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller SI, Ernst RK, Bader MW. 2005. LPS, TLR4 and infectious disease diversity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 36–46 10.1038/nrmicro1068 (doi:10.1038/nrmicro1068) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schröder NW, Schumann RR. 2005. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of Toll-like receptors and susceptibility to infectious disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5, 156–164 10.1016/s1473-3099(05)70023-2 (doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(05)70023-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piertney SB, Oliver MK. 2006. The evolutionary ecology of the major histocompatibility complex. Heredity 96, 7–21 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800724 (doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800724) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson JA, Friberg IM, Bolch L, Lowe A, Ralli C, Harris PD, Behnke JM, Bradley JE. 2009. Immunomodulatory parasites and Toll-like receptor-mediated tumour necrosis factor alpha responsiveness in wild mammals. BMC Biol. 7, 16. 10.1186/1741-7007-7-16 (doi:10.1186/1741-7007-7-16) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tschirren B, Råberg L, Westerdahl H. 2011. Signatures of selection acting on the innate immunity gene Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) during the evolutionary history of rodents. J. Evol. Biol. 24, 1232–1240 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02254.x (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02254.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurtenbach K, Hanincova K, Tsao JI, Margos G, Fish D, Ogden NH. 2006. Fundamental processes in the evolutionary ecology of Lyme borreliosis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 660–669 10.1038/nrmicro1475 (doi:10.1038/nrmicro1475) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dennis DT, Hayes EB. 2002. Epidemiology of Lyme borreliosis. In Lyme borreliosis: biology, epidemiology and control (eds Gray J, Kahl O, Lane RS, Stanek G.), pp. 251–280 Oxford, UK: CABI Publications [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostfeld RS. 2011. Lyme disease: the ecology of a complex system. New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirschfeld M, Kirschning CJ, Schwander R, Wesche H, Weis JH, Wooten RM, Weis JJ. 1999. Cutting edge: inflammatory signalling by Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins is mediated by Toll-like receptor 2. J. Immunol. 163, 2382–2386 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wooten RM, Ma Y, Yoder RA, Brown JP, Weis JH, Zachary JF, Kirschning CJ, Weis JJ. 2002. Toll-like receptor 2 is required for innate, but not acquired, host defense to Borrelia burgdorferi. J. Immunol. 168, 348–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alexopoulou L, Thomas V, Schnare M, Lobet Y, Anguita J, Schoen RT, Medzhitov R, Fikrig E, Flavell RA. 2002. Hyporesponsiveness to vaccination with Borrelia burgdorferi OspA in humans and in TLR1- and TLR2-deficient mice. Nat. Med. 8, 878–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roper RJ, et al. 2001. Genetic control of susceptibility to experimental Lyme arthritis is polygenic and exhibits consistent linkage to multiple loci on chromosome 5 in four independent mouse crosses. Genes Immun. 2, 388–397 10.1038/sj.gene.6363801 (doi:10.1038/sj.gene.6363801) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dennis VA, Dixit S, O'Brien SM, Alvarez X, Pahar B, Philipp MT. 2009. Live Borrelia burgdorferi spirochetes elicit inflammatory mediators from human monocytes via the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Infect. Immun. 77, 1238–1245 10.1128/iai.01078-08 (doi:10.1128/iai.01078-08) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schröder NWJ, et al. 2005. Heterozygous Arg753Gln polymorphism of human TLR2 impairs immune activation by Borrelia burgdorferi and protects from late stage Lyme disease. J. Immunol. 175, 2534–2540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurtenbach K, Schäfer SM, De Michelis S, Etti S, Sewell HS. 2002. Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in the vertebrate host. In Lyme borreliosis: biology, epidemiology and control (eds Gray J, Kahl O, Lane RS, Stanek G.), pp. 117–148 Oxford, UK: CABI Publications [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurtenbach K, Kampen H, Dizij A, Arndt S, Seitz HM, Schaible UE, Simon MM. 1995. Infestation of rodents with larval Ixodes ricinus (Acari, Ixodidae) is an important factor in the transmission cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. in German woodlands. J. Med. Entomol. 32, 807–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wandeler P, Ravaioli SR, Bucher TB. 2008. Microsatellite DNA markers for the snow vole (Chionomys nivalis). Mol. Ecol. Res. 8, 637–639 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.02028.x (doi:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.02028.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hellgren O, Andersson M, Råberg L. 2011. The genetic structure of Borrelia afzelii varies with geographic but not ecological sampling scale. J. Evol. Biol. 24, 159–167 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02148.x (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02148.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tschirren B, Andersson M, Scherman K, Westerdahl H, Råberg L. 2012. Contrasting patterns of diversity and population differentiation at the innate immunity gene Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) across populations of two sympatric rodent species. Evolution 66, 720–731 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01473.x (doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01473.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gautam JK, Ashish, Comeau LD, Krueger JK, Smith MF. 2006. Structural and functional evidence for the role of the TLR2 DD loop in TLR1/TLR2 heterodimerization and signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 30 132–30 142 10.1074/jbc.M602057200 (doi:10.1074/jbc.M602057200) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin MS, Kim SE, Heo JY, Lee ME, Kim HM, Paik SG, Lee HY, Lee JO. 2007. Crystal structure of the TLR1-TLR2 heterodimer induced by binding of a tri-acylated lipopeptide. Cell 130, 1071–1082 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.008 (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drummond AJ, Ashton B, Cheung M, Heled J, Kearse M, Moir R, Stones-Havas S, Thierer T, Wilson A. 2009. Geneious v. 4.6. See http://www.geneious.com [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephens M, Scheet P. 2005. Accounting for decay of linkage disequilibrium in haplotype inference and missing-data imputation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76, 449–462 10.1086/428594 (doi:10.1086/428594) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stephens M, Smith NJ, Donnelly P. 2001. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 978–989 10.1086/319501 (doi:10.1086/319501) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fay JC, Wu CI. 2000. Hitchhiking under positive Darwinian selection. Genetics 155, 1405–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li HP. 2011. A new test for detecting recent positive selection that is free from the confounding impacts of demography. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 365–375 10.1093/molbev/msq211 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msq211) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Librado P, Rozas J. 2009. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25, 1451–1452 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187 (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jensen JD, Kim Y, DuMont VB, Aquadro CF, Bustamante CD. 2005. Distinguishing between selective sweeps and demography using DNA polymorphism data. Genetics 170, 1401–1410 10.1534/genetics.104.038224 (doi:10.1534/genetics.104.038224) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clement M, Posada D, Crandall K. 2000. TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol. Ecol. 9, 1657–1660 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01020.x (doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01020.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson J, Higgins D, Gibson T. 1994. Clustal W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673 (doi:10.1093/nar/22.22.4673) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Eswar N, Eramian D, Webb B, Shen M, Sali A. 2008. Protein structure modeling with Modeller. Methods Mol. Biol. 426, 145–159 10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_8 (doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-058-8_8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Råberg L. 2012. Infection intensity and infectivity of the tick-borne pathogen Borrelia afzelii. J. Evol. Biol. 25, 1448–1453 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2012.02515.x (doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2012.02515.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gern L, Siegenthaler M, Hu CM, Leubagarcia S, Humair PF, Moret J. 1994. Borrelia burgdorferi in rodents (Apodemus flavicollis and A. sylvaticus): duration and enhancement of infectivity for Ixodes ricinus ticks. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 10, 75–80 10.1007/bf01717456 (doi:10.1007/bf01717456) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gliwicz J. 1988. Seasonal dispersal in non-cyclic populations of Clethrionomys glareolus and Apodemus flavicollis. Acta Theriol. 33, 263–272 [Google Scholar]

- 49.R Development Core Team 2011. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. See http://www.R-project.org.

- 50.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B. 2011. lme4: linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. R package version 0.999375-42. See http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kozakiewicz M, Choluj A, Kozakiewicz A. 2007. Long-distance movements of individuals in a free-living bank vole population: an important element of male breeding strategy. Acta Theriol. 52, 339–348 10.1007/bf03194231 (doi:10.1007/bf03194231) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hughes VL, Randolph SE. 2001. Testosterone depresses innate and acquired resistance to ticks in natural rodent hosts: a force for aggregated distributions of parasites. J. Parasitol. 87, 49–54 10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[0049:tdiaar]2.0.co;2 (doi:10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[0049:tdiaar]2.0.co;2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Viitala J, Hakkarainen H, Ylonen H. 1994. Different dispersal in Clethrionomys and Microtus. Ann. Zool. Fenn. 31, 411–415 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Raby AC, et al. 2011. TLR activation enhances C5a-induced pro-inflammatory responses by negatively modulating the second C5a receptor, C5L2. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 2741–2752 10.1002/eji.201041350 (doi:10.1002/eji.201041350) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kurtenbach K, De Michelis S, Etti S, Schafer SM, Sewell HS, Brade V, Kraiczy P. 2002. Host association of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato: the key role of host complement. Trends Microbiol. 10, 74–79 10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02298-3 (doi:10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02298-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ingvarsson PK. 2010. Natural selection on synonymous and nonsynonymous mutations shapes patterns of polymorphism in Populus tremula. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 650–660 10.1093/molbev/msp255 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msp255) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chamary JV, Hurst LD. 2005. Evidence for selection on synonymous mutations affecting stability of mRNA secondary structure in mammals. Genome Biol. 6, R75. 10.1186/gb-2005-6-9-r75 (doi:10.1186/gb-2005-6-9-r75) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kimura M. 1983. The neutral theory of molecular evolution. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 59.Biswas S, Akey JM. 2006. Genomic insights into positive selection. Trends Genet. 22, 437–446 10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.005 (doi:10.1016/j.tig.2006.06.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Moody KD, Terwilliger GA, Hansen GM, Barthold SW. 1994. Experimental Borrelia burgdorferi infection in Peromyscus leucopus. J. Wildl. Dis. 30, 155–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hofmeister EK, Ellis BA, Glass GE, Childs JE. 1999. Longitudinal study of infection with Borrelia burgdorferi in a population of Peromyscus leucopus at a Lyme disease-enzootic site in Maryland. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 60, 598–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chambert T, Staszewski V, Lobato E, Choquet R, Carrie C, McCoy KD, Tveraa T, Boulinier T. 2013. Exposure of black-legged kittiwakes to Lyme disease spirochetes: dynamics of the immune status of adult hosts and effects on their survival. J. Anim. Ecol. 81, 986–995 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2012.01979.x (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2012.01979.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Obbard DJ, Jiggins FM, Bradshaw NJ, Little TJ. 2011. Recent and recurrent selective sweeps of the antiviral RNAi gene Argonaute-2 in three species of Drosophila. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 1043–1056 10.1093/molbev/msq280 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msq280) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Acevedo-Whitehouse K, Cunningham AA. 2006. Is MHC enough for understanding wildlife immunogenetics? Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 433–438 10.1016/j.tree.2006.05.010 (doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.05.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alcaide M, Edwards SV. 2011. Molecular evolution of the Toll-like receptor multigene family in birds. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 1703–1715 10.1093/molbev/msq351 (doi:10.1093/molbev/msq351) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]