Abstract

Play has been defined as apparently functionless behaviour, yet since play is costly, models of adaptive evolution predict that it should have some beneficial function (or functions) that outweigh its costs. We provide strong evidence for a long-standing, but poorly supported hypothesis: that early social play is practice for later dominance relationships. We calculated the relative dominance rank by observing the directional outcome of playful interactions in juvenile and yearling yellow-bellied marmots (Marmota flaviventris) and found that these rank relationships were correlated with later dominance ranks calculated from agonistic interactions, however, the strength of this relationship attenuated over time. While play may have multiple functions, one of them may be to establish later dominance relationships in a minimally costly way.

Keywords: play, dominance, practice hypothesis, function of play, yellow-bellied marmots

1. Introduction

Play is defined as apparently purposeless behaviour [1], but because it takes time and consumes energy [2,3] and exposes animals to various risks—including the risk of predation [4,5], it must have substantial benefits [6]. However, despite over a century of study, the functional significance of play behaviour is not readily known even though many non-mutually exclusive hypotheses persist in the literature [6–9]. Indeed, not only are hypotheses non-mutually exclusive, play may have different functions at different parts of an animal's life [8]. A fundamental and ethical challenge in studying play is that it is difficult to deprive animals only of play (but see [10,11]) and that deprivation of play typically impedes normal development [12,13]. Thus, we must often accept correlative support for hypotheses.

One widely suggested functional hypothesis was suggested over a century ago. The ‘practice hypothesis’ suggests that play provides an opportunity to practice and refine skills that will be needed later in adulthood [14]. Object play improves motor skills, enhances cerebellar synaptogenesis and modifies muscle fibres [15,16] important for survival [8], but animals may also play socially [1,6,17]. Can social play also be practice for later dominance?

There have been relatively few studies that have asked whether play is practice for later dominance, defined here based on outcomes of pairwise agonistic interactions in which the dominant individual ‘beats’ its opponent if the opponent signals submission [18]. Support for the practice hypothesis is equivocal and often requires evaluating patterns, rather than outcomes [16]. Studies with captive gelada baboons (Theropithecus gelada, [19]; 21 subjects observed for 513 h) and captive wolves (Canis lupus, [20]; nine subjects observed for 1 year) found no support for the hypothesis. The degree of asymmetry in adolescent chimpanzee play was associated with dominance rank [21], but this study was based on only four subjects studied for 633 h over 30 months. Sexual differences in play fighting in dogs (Canis familiaris) were used to support the play as practice for dominance hypothesis ([22]; 24 subjects, 819 h of observation over 13 weeks). Notably, these (sometimes detailed studies) were conducted over a relatively short time period, or they were studies that employed relatively few subjects.

However, even longer-term studies with more individuals have revealed equivocal or weakly correlative support. Ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta) play becomes less symmetrical with age; a finding that was used to support the practice hypothesis ([23]; 25 subjects, 14 months of observation). Based on 10 year of observations of 44 subjects, play-mounting in spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta), but not social play (the most common and persistent form of play in this species) was positively associated with the maternal rank of immature individuals [24]. Yet by contrast, another long-term study of the practice hypothesis, which lasted 6 years and focused on 76 meerkats (Suricata suricata), found that play fighting successes were not associated with later dominance rank [25].

In the light of the equivocal support for the practice hypothesis, we studied the relationship between early play behaviour and later dominance in a free-living population of yellow-bellied marmots (Marmota flaviventris). Yellow-bellied marmots are particularly well suited for a study of the relationship between early play and later dominance for the following reasons. First, they are facultatively social rodents that live in a variety of group sizes; some with overlapping generations [26]. Second, they play during the first 2 years of their lives (as pups—animals less than a year old and as yearlings—animals 1 year old [27,28]), and this creates an opportunity to test two complementary hypotheses (see below). Third, our population has been studied since 1962, which enables us to draw upon a wealth of information about their long-term social interactions [29,30] and the function of dominance [31], as well as an extensive observational dataset [32]. Fourth, a previous study of yellow-bellied marmot play [28] found that playing marmots failed to self-handicap themselves (which means that larger and potentially more dominant individuals who were actively holding down or chasing another individual did not suddenly reverse roles), suggesting that play might enhance competitive skills and is probably involved in dominance. Importantly, the relationships between early play and later dominance were not evaluated in this previous short-term study.

If the practice hypothesis explains one potential function of marmot play, we predicted that dominance ranks calculated from winners and losers of playful interactions early in life should be associated with an individual's subsequent dominance rank calculated from agonistic behaviour outcomes in adulthood. We tested this hypothesis in two ways. First, we asked whether dominance ranks calculated from affiliative play behaviour as pups predicted relative dominance ranks based on agonistic outcomes as yearlings. If so, this would be good support for a delayed function of play. Second, we asked whether dominance ranks calculated from all observed play (as both pups and yearlings), predicted relative dominance rank later in life.

We acknowledge that play in yearlings might be a means of negotiating immediate dominance relationships and might therefore have an immediate function [33]. Nevertheless, because play is restricted to only pups and yearlings, it is worth looking for potential future effects of play.

A number of additional factors that influence dominance must be acknowledged. First, because play may be influenced by body condition [3,34], and because body condition is associated with dominance rank in yellow-bellied marmots [31], we statistically controlled for the effects of body condition (by calculating a standardized body mass; see below) when studying the relationship between early play and later dominance. Second, because the rate of play could conceivably have both immediate and delayed consequences, we statistically controlled for the rate of play when examining the relationship between play ranks and later dominance ranks. Finally, because the stability of pairwise agonistic and affiliative relationships across ontogeny has been extensively investigated elsewhere, and because kinship fails to protect marmots of any life-history stage from losing fights [30,32], we focus here on the precise effect of play on an individual's later relative social rank, rather than on characterizing the patterning of ontogenetic shifts between pairs of marmots based on kinship; an individual's relative social rank in its group has important fitness consequences for individuals in this species [31].

2. Material and methods

(a). Subjects and data collection

From 2002 to 2011, we monitored wild yellow-bellied marmots located around the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory (RMBL) in Gunnison County, Colorado (38°57′29″ N, 106°59′06″ W, elevation approx. 2890 m). All subjects were individually recognized and part of a long-term study initiated in 1962 [32]. During the active season, we regularly trapped marmots in Tomahawk live traps set around burrow entrances on a bi-weekly schedule with minimal disturbance to the animals [35]. Upon capture, we transferred each marmot into a canvas, handling bag where we weighed, sexed and collected samples (faeces and blood). Marmots were individually marked with uniquely numbered ear tags and Nyanzol cattle dye at first capture. Marmots were classified into three discrete life-history stages, each separated by annual periods of hibernation: pups, yearlings and adults (sexually mature animals, more than or equal to 2 years old).

From April to September, observers monitored each colony site during times of peak activity in the mornings (07.00–10.00 h) and afternoons (16.00–19.00 h) on most days using binoculars and spotting scopes from distances (20–150 m) that did not obviously influence subject behaviour. At each observation session, we recorded all individuals that were present and the duration of that sampling period. We used all-occurrence sampling to record the initiator and the recipient of each social exchange [36]. Affiliative play behaviour included all accounts of play biting, boxing, chasing, grabbing, slapping, pushing, pouncing, mounting and wrestling (ethogram and details about data collection are in the electronic supplementary material). Directionality of affiliative play was determined by whom was displaced at the end of an interaction. Agonistic interactions were all observations of aggression and displacements for which the initiator directed aggression towards, or actively displaced, its recipient. Quantified both ways, pairwise matrices of ‘wins and losses’ were subsequently used to generate two separate measures of dominance. We calculated the rate of play by summing all observed playful interactions (regardless of outcome) and divided this by the number of days that animal was seen above ground.

(b). Rank assignments

We calculated ranks based on outcomes from play or agonistic interactions using the Clutton–Brock index, a method that is particularly tolerant of missing pairwise interactions and weights wins highly [37–39]. For each marmot in a colony-year, this index is based on the number of marmots that the focal marmot beat (B) plus the total number of marmots which they beat, excluding the subject (Σb), as well as the number of marmots which it lost to (L) plus the total number which they lost to, excluding the subject (Σl). Our index was therefore: (B + Σb + 1)/(L + Σl + 1); ones were added to reduce the chances of an anomalous result for individuals never observed to beat others or to be beaten. To account for variation in group size, we transformed absolute ranks to relative ranks, where the lowest-ranking individual within a colony-year was 0, and the highest-ranking individual was 1 [31].

(c). Statistical analyses

We fitted linear mixed models (LMM) in R [40] to ask whether an individual's relative rank based on play outcomes as a pup predicted its relative rank based on agonistic outcomes as a yearling, and we also asked whether the rank calculated from all observed play (both as pups and yearlings) predicted its relative rank based on agonistic outcomes as an adult in subsequent years. In all models, we included ‘marmot identity’ as a random effect to account for repeated measures on the same individuals and used likelihood ratio tests to determine whether random effects improved the fit of each model. We calculated the ‘repeatability’ of individual effects as the percentage of residual variance in the LMM attributed to each of these random effects [41]. Random effects of ‘colony’ and ‘year’ were added as necessary to control for variation in behaviours attributed to site and annual variation, respectively. We study marmots along an elevational gradient and our higher-elevation colonies have a shorter growing season than our lower-elevation colonies [42,43]. This phenological difference has a variety of life-history consequences so we included ‘valley location’ as another independent variable. Males are generally dominant to females [31], so we also included sex as an independent variable. Because marmots do not engage in compensatory growth [44], following the methods reported in [45], we estimated August body mass and used this measure as a covariate in all analyses. The rate of early play was included as a covariate to permit us to isolate the effect of play dominance on later dominance. Finally, because the effects of early experiences are expected to attenuate over time, we included a final variable, the difference in years between ranks based on early play and later agonistic interaction, as an independent variable. We tested for all two-way interactions and only included these terms when doing so increased the fit of our model (smallest Akaike information criterion; see the electronic supplementary material, table 2a–c for excluded terms). p-values were calculated from t-statistics after interactions were excluded. Values for excluded terms are based on adding each term to our final models. We set our alpha to 0.05 and report the results of two-tailed tests. Data are archived at www.eeb.ucla.edu/Faculty/Blumstein/MarmotsOfRMBL/data.html.

3. Results

We recorded a total of 27 493 social interactions involving 803 marmots (n = 429 males and 374 females). Of these, 4020 and 8556 events were positively identified as agonistic or playful, respectively. On average, each individual was observed in 67 ± 4 (mean ± s.e.) social interactions across this study, including 17 ± 2 agonistic (n = 250 male and 212 females) and 28 ± 2 playful interactions (n = 344 males and 274 females). Assignments of clear winners and losses were possible for 4910 interactions (n = 2817 play and 2093 agonistic outcomes) involving a total of 509 individuals (n = 282 males and 227 females). On average, each individual was involved in 19.3 ± 1.1 social interactions with clear outcomes (n = 13.0 ± 0.9 play and 10.8 ± 0.8 agonistic outcomes). These outcomes were used to generate a total of 110 colony-year matrices, of which 64 matrices contained data on play, and 56 matrices contained data on agonistic interactions. Matrices were limited by sufficient observational data for each year of the study for each social group. Ultimately, relative ranks for each colony-year therefore totalled 971 rank assignments based on play (2002–2010, n = 222 males and 179 females) and 803 rank assignments based on agonistic interactions (2003–2011, n = 217 males and 190 females). The specific data reported here were collected during 9157 h of observation at seven main colony sites (lower valley: Bench, River and Gothic townsite; upper valley: Boulder; Marmot Meadow; Picnic). A total of 775 matched relative ranks based on play early in life and agonistic outcomes later in life involved 279 participants (n = 152 male and 127 females).

Overall, the relative agonistic dominance rank of an individual marmot (n = 152 males and 127 females) based on fight outcomes later in life was predicted by that individual's relative rank based on the outcomes of play interactions early in life (relative rank based on play: estimate ± s.e. = 0.136 ± 0.048, t = 2.819, p = 0.005; table 1a). This was the case after controlling for the significant effects of sex—males were generally socially dominant to females (sex: 0.064 ± 0.029, t = 2.195, p = 0.028). Relative dominance ranks based on agonistic interactions increased as the difference in years between ranks based on early play and later agonistic interactions passed (years between measures: 0.037 ± 0.008, t = 4.976, p < 0.00001). Moreover, because adults were socially dominant to yearlings, agonistic ranks measured for yearlings were lower than those of adults (yearling stage: −0.137 ± 0.028, t = −4.965, p < 0.00001). Finally, the individuals with high late season body masses as immature individuals at the time play was recorded were generally of higher agonistic rank later in life than were those individuals of low body masses, although this finding was not statistically significant (mass: 0.00002 ± 0.00001, t = 1.955, p = 0.051). The random effect of the individual improved the fit of the model (likelihood ratio test: χ21 = 30.7, p < 0.00001), explaining 33.3 per cent of the variation in the relative dominance rank of yearling or adult marmots. However, random effects of year, colony and valley location failed to improve the fit of this or any other model tested (likelihood ratio tests: d.f. = 1 for each, p = 1.000).

Table 1.

Independent variables predicting the relative dominance rank of yellow-bellied marmots based on agonistic interactions.

| estimate ± s.e. | t-value | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) full dataset: early play of pups and yearlings predicts dominance in subsequent yearsa | |||

| (intercept) | 0.336 ± 0.047 | 7.216 | <0 |

| life-history stage when dominance recorded (yearling) | −0.137 ± 0.028 | −4.966 | <0.00001 |

| no. of years between play and agonistic measures of rank | 0.038 ± 0.008 | 4.986 | <0.00001 |

| relative rank based on outcomes of play | 0.136 ± 0.048 | 2.819 | 0.005 |

| sex (male) | 0.064 ± 0.029 | 2.208 | 0.028 |

| body mass for season in which play recorded | 0.00002 ± 0.00001 | 1.955 | 0.051 |

| rate of early play | −0.014 ± 0.035 | −0.403 | 0.567 |

| (b) reduced dataset: play outcomes for pups predicts relative dominance rank of yearlingsb | |||

| (intercept) | 0.103 ± 0.108 | 0.950 | 0.343 |

| relative rank based on outcomes of play | 0.179 ± 0.053 | 3.371 | 0.0009 |

| sex (male) | 0.334 ± 0.142 | 2.354 | 0.019 |

| body mass for season in which play recorded | 0.00009 ± 0.00008 | 1.202 | 0.230 |

| rate of early play | 0.048 ± 0.059 | 0.828 | 0.408 |

| sex × body mass | −0.0002 ± 0.0001 | −1.757 | 0.080 |

| (c) reduced dataset: limited effects of early play on relative dominance of adultsc | |||

| (intercept) | 0.335 ± 0.073 | 4.667 | <0.000001 |

| age as an adult when dominance measured | 0.040 ± 0.008 | 5.280 | <0.000001 |

| life-history stage for which play recorded (yearling) | −0.087 ± 0.072 | −1.210 | 0.227 |

| relative rank based on outcomes of play | 0.073 ± 0.078 | 0.934 | 0.351 |

| body mass for season in which play recorded | 0.00005 ± 0.00004 | 1.272 | 0.204 |

| sex (male) | 0.023 ± 0.052 | 0.418 | 0.676 |

| rate of early play | −0.022 ± 0.039 | −0.570 | 0.569 |

aData on early play of pups and yearlings (2002–2010) and later dominance (2003–2011) ranks based on n = 281 and 494 measures, respectively, on 152 males and 127 females at seven colony sites.

bData on pup play (2002–2010) and yearling dominance (2003–2011) ranks are based on n = 148 males and 122 females, respectively, at seven colony sites.

cData on early play of pups and yearlings (2002–2010) and later dominance (2003–2011) ranks of adults based on n = 133 and 372 measures on 36 males and 72 females, respectively, at seven colony sites.

Given our findings that relative dominance measures change over the life course, we next investigated these patterns to understand the precise nature of these ontogenetic shifts and to assess the extent to which the effects of early ranks based on play outcomes persisted into adulthood. Specifically, two subsequent analyses focused on subsets of the data for which agonistic dominance was measured for: (i) yearlings (n = 148 males and 122 females), and (ii) adults (n = 36 males and 72 females).

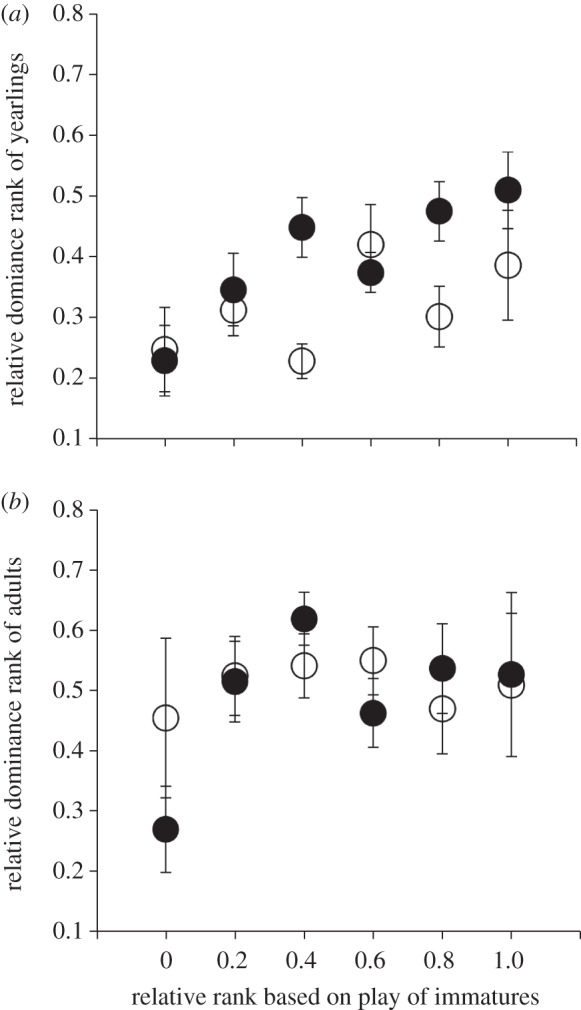

First, as was the case for the full dataset, the model explaining agonistic ranks for yearlings revealed that the relative rank of pups based on the outcome of play positively predicted the relative dominance rank based on agonistic interactions of yearlings (play rank: 0.179 ± 0.053, t = 3.371, p = 0.0009) after accounting for yearling males generally being socially dominant to yearling females in agonistic interactions (0.334 ± 0.142, t = 2.354, p = 0.019; figure 1a and table 1b). Importantly, late season body mass for pups failed to predict relative dominance ranks of yearlings (0.000009 ± 0.00008, t = 1.202, p = 0.230; table 1b) nor was an interaction between sex and body mass significant (–0.0002 ± 0.0001, t = −1.757, p = 0.080). Finally, there was no effect of the rate of early play on later dominance (0.048 ± 0.059, t = 0.828, p = 0.408).

Figure 1.

Relationships between the mean ± s.e. relative ranks based on the outcomes of (a) play as pups and later agonistic (dominance) interactions as yearlings (n = 148 males, shown as filled-in circles and 122 females, shown as open circles) and (b) play as immature (pups or yearlings) and agonistic interactions for those same individuals as 2 year old adults (n = 32 males and 67 females as pups and yearlings. Ranks for adults are pooled because we detected no sex difference (see text). Relative ranks based on play are shown separately for pups (open circles, n = 97) and yearlings (filled-in circles, n = 102) to account for differences between life-history stages. Because dominance ranks increased as during between as age of adults increased, data shown here are limited to the first year of adulthood.

Interestingly, the effects of early ranks based on play attenuated over time such that they failed to significantly predict the relative agonistic rank for adults, although this relationship remained positive (play rank of immature individuals: 0.073 ± 0.078, t = 0.934, p = 0.351; figure 1b and table 1c). Sex was no longer a significant predictor of adult dominance rank (sex: 0.023 ± 0.052, t = 0.418, p = 0.676; table 1c). Instead, the absolute age of individuals predicted agonistic dominance, with older adults being socially dominant to younger ones (age: 0.040 ± 0.008, t = 5.280, p < 0.000001). This effect of age as the main determinant of dominance rank in adults persisted after accounting for the effects of the life-history stage at which play was recorded, with trends remaining for yearlings generally being socially subordinate to adults (−0.087 ± 0.072, t = −1.200, p = 0.227), and the tendency for heavier immature animals to be more socially dominant as adults than were lighter immature animals (0.00005 ± 0.00004, t = 1.272, p = 0.204). Finally, the rate of early play had no effect on later dominance rank (−0.022 ± 0.039, t = −0.570, p = 0.569). As in the full dataset, individual identity was important above and beyond the effects of play, improving the fit of the model and explaining 51.6 per cent of the variation in the relative dominance rank of adults (likelihood ratio test: χ21 = 91.3, p < 0.00001).

4. Discussion

We have presented, what we believe is, the strongest correlative evidence showing that early social play behaviour has functional consequences on later dominance rank. We acknowledge that correlative evidence for functions of play have critics [25,46], but also note that we are unaware of other studies that have attempted to statistically control for as many potentially important variables as we have.

We know from the previous studies, and saw in our results here, that marmots vary in consistent ways—they have personalities [47]—which may have both an endocrine [35] and a genetic [48] basis. Thus, it was essential to statistically control for individual effects so as to isolate the relationship between play and later rank. Our use of linear mixed effect models permitted us to control for individuality and other potentially important factors that could influence rank in a novel way not previously done in other studies on play. These newly available statistical methods therefore offer new opportunities to advance our understanding of the functional significance of play in free-ranging animals.

There are at least two other proximate hypotheses that might explain the relationship between early play and later dominance. First, the amount of early play (independent of rank) could have an immediate benefit in terms of increased survival (as has been reported in brown bears (Ursus arctos) [49]) or may be a mechanism that influences later dominance. We statistically controlled for the effect of the rate of early play on dominance and were able to reject this potential mechanism accounting for later rank. Second, boldness (independent of rank) could be another proximate driver of dominance in adults. For instance, in rats, neurochemical brain differences influence boldness, and boldness is associated with dominance in adults [50]. Formal path analysis on a novel dataset would be required to identify this proximate pathway but this analysis was beyond the scope of our study. Thus, while we have identified a functional relationship between play and its consequences and have rejected one putative mechanistic hypothesis, the precise mechanism underlying this relationship is not fully identified.

Nonetheless, marmots that were socially dominant as pups within the context of play held higher dominance ranks in the context of agonistic dominance as yearlings than yearlings that previously held relatively lower ranks during play. This is strong support for a delayed function of play [35]. We also found that the outcomes of pup and yearling play were positively associated with adult rank, although we acknowledge that yearling play may also have an immediate function. However, the effect attenuated with the number of years between when play occurred and when dominance was measured. Importantly, the strong effect of pup play on social rank as yearlings was not influenced by body condition, a finding that clarifies the importance of play and suggests that it has functional consequences.

Dominance ranks for yearlings and 2-year olds are probably of particular importance for marmots. Almost all yearling males disperse as do about 50 per cent of yearling females [51] and, as in other taxa [52], social cohesion plays an important role in explaining philopatry in marmots [53,54]. Two-year old female marmots are likely to be reproductively suppressed if they are in a group with older females [55], and we expect, but have not formally evaluated the hypothesis, that dominance rank is likely to explain some variation in suppression. During the years of our study, the population was growing [56] and almost all females reproduced annually; thus our dataset was not sufficiently variable to permit us to study the effects of social dominance on reproductive dominance. Nonetheless, our paper has demonstrated a link between play and later social dominance, and this finding suggests that early play behaviour appears to represent a particularly low-cost method to establish dominance in later life.

Because wounding or mortality resulting from direct combat can be costly, natural selection is expected to favour the ability of individuals to assess the dominance status of group-mates outside the context of direct fighting [57]. Indeed, meerkats have been observed being injured during fights [25], and we have some evidence that marmots can harm each other while fighting (D. T. Blumstein 2012, personal observation). However, in neither of these species has wounding or mortality been observed as direct consequence of play. Play, however, is not without costs if individuals are injured while playing, as has been reported in Siberian ibex (Capra ibex sibrica) kids [58], if it reduces an individual's ability to attend to predators, as has been reported in South American fur seals (Arctocephalus australis) and golden marmots (Marmota caudata aurea) [4,5] or if it is energetically costly, as has been reported in Belding's ground squirrels (Urocitellus beldingi) [34].

An experimental study of the effects of early testosterone exposure on play fighting and later dominance in rats found that neonatal exposure to testosterone enhanced play behaviour, but there were no effects detected on later dominance [59]. This finding suggests that in rats, the two systems (play and dominance) are, in a proximate sense, independent. While we currently lack data on the relationship between circulating testosterone and play in marmots, androgenized females in this population initiate the most social interactions (which include play) [60]. Thus, perhaps organizational effects [61] of testosterone are required to functionally link play outcomes with later dominance outcomes. Rank-related maternal androgens indeed have crucial organizational effects for wild spotted hyenas, explaining both rates of play-mounting and aggression in immature individuals [62].

While we have provided correlative evidence of one demonstrable function of play, we acknowledge that play is multi-faceted and the nature and function of play is likely to vary among species [6,8], and indeed even through ontogeny. Nonetheless, social play may be a relatively low-cost way to develop dominance relationships and the results of the current study are novel in that they provide, to our knowledge, the first definitive link between early play and later dominance within social groups of free-living mammals.

Acknowledgements

Marmots were studied under animal research protocols approved by UCLA and the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory.

We thank all the marmoteers who helped collect data over the past decade, Julien Martin and Adrianna Maldonado-Chapparo for help developing our database, and Marc Bekoff, Jill Mateo and two anonymous reviewers for comments on a previous version of this manuscript. The past decade of financial support came from the UCLA Academic Senate and Division of Life Sciences, National Geographic Society, the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory (research fellowship) and NSF-IDBR-0754247 and DEB-1119660 (to D.T.B.); NSF-DBI 0242960, 0731346 (to the RMBL).

References

- 1.Bekoff M, Byers JA. 1981. A critical reanalysis of the ontogeny and phylogeny of mammalian social and locomotor play: an ethological hornet's nest. In Behavioral development: the Bielefeld interdisciplinary project (eds Immelmann K, Barlow GW, Petrinovich L, Main M.), pp. 296–337 Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin P. 1984. The time and energy costs of play behaviour in the cat. Z. Tierpsychol. 64, 298–312 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1984.tb00365.x (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1984.tb00365.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron EZ, Linklater WL, Stafford KJ, Minot EO. 2008. Maternal investment results in better foal condition through increased play behaviour in horses. Anim. Behav. 76, 1511–1518 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.07.009 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.07.009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harcourt R. 1991. Survivorship costs of play in the South American fur seal. Anim. Behav. 42, 509–511 10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80055-7 (doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80055-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumstein DT. 1998. Quantifying predation risk for refuging animals: a case study with golden marmots. Ethology 104, 501–516 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1998.tb00086.x (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1998.tb00086.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagen R. 1981. Animal play behavior. New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barber N. 1991. Play and energy regulation in mammals. Q. Rev. Biol. 66, 129–147 10.1086/417142 (doi:10.1086/417142) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spinka M, Newberry RC, Bekoff M. 2001. Mammalian play: training for the unexpected. Q. Rev. Biol. 76, 141–168 10.1086/393866 (doi:10.1086/393866) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burghardt GM. 2005. The genesis of animal play: testing the limits. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press [Google Scholar]

- 10.Einon DF, Morgan MJ, Kibbler CC. 1978. Brief periods of socialization and later behavior in the rat. Dev. Psychobiol. 11, 213–225 10.1002/dev.420110305 (doi:10.1002/dev.420110305) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell HC, Pellis SM, Kolb B. 2010. Juvenile peer play experience and the development of the orbitofrontal and medial prefrontal cortices. Behav. Brain Res. 207, 7–13 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.09.029 (doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2009.09.029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bekoff M. 1976. Animal play: problems and perspectives. Persp. Ethol. 2, 165–188 10.1007/978-1-4615-7572-6_4 (doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-7572-6_4) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bekoff M. 1976. The social deprivation paradigm: who's being deprived of what? Dev. Psychobiol. 9, 499–500 10.1002/dev.420090603 (doi:10.1002/dev.420090603) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Groos K. 1898. The play of animals (Transl. by E.L. Bladwin) London, UK: D. Appleton & Co [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bekoff M. 1988. Motor-training and physical fitness: possible short-and long term influences on the development of individual differences in behavior. Dev. Psychobiol. 21, 601–612 10.1002/dev.420210610 (doi:10.1002/dev.420210610) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byers JA, Walker C. 1995. Refining the motor training hypothesis for the evolution of play. Am. Nat. 146, 25–40 10.1086/285785 (doi:10.1086/285785) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nunes S, Muecke E-M, Lancaster LT, Miller NA, Mueller MA, Muelhaus J, Castro L. 2004. Functions and consequences of play behaviour in juvenile Belding's ground squirrels. Anim. Behav. 68, 27–37 10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.06.024 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.06.024) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowell TE. 1974. The concept of social dominance. Behav. Biol. 11, 131–154 10.1016/S0091-6773(74)90289-2 (doi:10.1016/S0091-6773(74)90289-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mancini G, Palagi E. 2009. Play and social dynamics in a captive herd of gelada baboons (Theropithecus gelada). Behav. Proc. 82, 286–292 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.07.007 (doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2009.07.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cordoni G. 2009. Social play in captive wolves (Canis lupus): not only an immature affair. Behaviour 146, 1363–1385 10.1163/156853909X427722 (doi:10.1163/156853909X427722) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paquette D. 1994. Fighting and playfighting in captive adolescent chimpanzees. Aggress. Behav. 20, 49–65 (doi:10.1002/1098-2337(1994)20:1<49::AID-AB2480200107>3.0.CO;2-C) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pal SK. 2010. Play behaviour during early ontogeny in free ranging dogs (Canis familiaris). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 126, 140–153 10.1016/j.applanim.2010.06.005 (doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2010.06.005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pereira ME. 1993. Agonistic interaction, dominance relation, and ontogentic trajectories in ring-tailed lemurs. In Juvenile primates (eds Pereria ME, Fairbanks LA.), pp. 285–305 New York, NY: Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanner JB, Smale L, Holekamp KE. 2007. Ontogenetic variation in the play behavior of spotted hyenas. J. Devel. Process. 2, 5–30 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharpe LL. 2005. Play fighting does not affect subsequent fighting success in wild meerkats. Anim. Behav. 69, 1023–1029 10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.07.013 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2004.07.013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blumstein DT, Armitage KB. 1999. Cooperative breeding in marmots. Oikos 84, 369–382 10.2307/3546418 (doi:10.2307/3546418) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nowicki S, Armitage KB. 1979. Behavior of juvenile yellow-bellied marmots: play and social integration. Z. Tierpsychol. 51, 85–105 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1979.tb00674.x (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1979.tb00674.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jamieson SH, Armitage KB. 1987. Sex differences in the play behavior of yearling yellow-bellied marmots. Ethology 74, 237–253 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1987.tb00936.x (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1987.tb00936.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wey TW, Blumstein DT. 2012. Social attributes and associated performance measures in marmots: bigger male bullies and weakly affiliating females have higher annual reproductive success. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 66, 1075–1085 10.1007/s00265-012-1358-8 (doi:10.1007/s00265-012-1358-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith JE, Chung LK, Blumstein DT. In press. Ontogeny and symmetry of social partner choice among free-living yellow-bellied marmots. Anim Behav. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang B, Wey TW, Blumstein DT. 2011. Correlates and consequences of dominance in a social rodent. Ethology 117, 573–585 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2011.01909.x (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2011.01909.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Armitage KB. 2010. Individual fitness, social behavior, and population dynamics of yellow-bellied marmots. In The ecology of place: contributions of place-based research to ecological understanding (eds Billick I, Price MV.), pp. 132–154 Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pellis S, Pellis V. 2009. The playful brain: venturing to the limits of neuroscience. Oxford, UK: Oneworld [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nunes S, Muecke E-M, Anthony JA, Baterbee AS. 1999. Endocrine and energetic mediation of play behavior in free-living Belding's ground squirrels. Horm. Behav. 36, 153–165 10.1006/hbeh.1999.1538 (doi:10.1006/hbeh.1999.1538) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith JE, Monclús R, Wantuck D, Florant GL, Blumstein DT. 2012. Fecal glucocorticoid metabolites in wild yellow-bellied marmots: experimental validation, individual differences and ecological correlates. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 178, 417–426 10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.06.015 (doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.06.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altmann J. 1974. Observational study of behaviour: sampling methods. Behaviour 49, 227–267 10.1163/156853974X00534 (doi:10.1163/156853974X00534) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clutton-Brock TH, Albon SD, Gibson RM, Guinness FE. 1979. The logical stag: adaptive aspects of fighting in red deer (Cervus elaphus L.). Anim. Behav. 27, 211–225 10.1016/0003-3472(79)90141-6 (doi:10.1016/0003-3472(79)90141-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bayly KL, Evans CS, Taylor A. 2006. Measuring social structure: a comparison of eight dominance indices. Behav. Proc. 73, 1–12 10.1016/j.beproc.2006.01.011 (doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2006.01.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bang A, Deshpande S, Sumana A, Gadagkar R. 2010. Choosing an appropriate index to construct dominance hierarchies in animal societies: a comparison of three indices. Anim. Behav. 79, 631–636 10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.12.009 (doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.12.009) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.R Development Core Team 2011. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lessells CM, Boag PT. 1987. Unrepeatable repeatabilities: a common mistake. Auk 104, 116–121 10.2307/4087240 (doi:10.2307/4087240) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Vuren D, Armitage KB. 1991. Duration of snow cover and its influence on life-history variation in yellow-bellied marmots. Can. J. Zool. 69, 1755–1758 10.1139/z91-244 (doi:10.1139/z91-244) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blumstein DT. 2009. Social effects on emergence from hibernation in yellow-bellied marmots. J. Mamm. 90, 1184–1187 10.1644/08-MAMM-A-344.1 (doi:10.1644/08-MAMM-A-344.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monclús R, Pang B, Blumstein DT. Submitted. Yellow-bellied marmots do not compensate for a late start: the role of maternal investment in shaping life-history trajectories. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozgul A, Childs DZ, Oli MK, Armitage KB, Blumstein DT, Olson LE, Tuljapurkar S, Coulson T. 2010. Coupled dynamics of body mass and population growth in response to environmental change. Nature 466, 482–485 10.1038/nature09210 (doi:10.1038/nature09210) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghiselin MT. 1982. On the evolution of play by means of artificial selection. Behav. Brain Sci. 5, 165. 10.1017/S0140525X00011043 (doi:10.1017/S0140525X00011043) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blumstein DT, Petelle MP, Wey TW. 2013. Defensive and social aggression: repeatable but independent. Behav. Ecol. 24, 457–461 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lea AJ, Blumstein DT, Wey TW, Martin JGA. 2010. Heritable victimization and the benefits of agonistic relationships. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 21 587–21 592 10.1073/pnas.1009882107 (doi:10.1073/pnas.1009882107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fagen R, Fagen J. 2004. Juvenile survival and benefits of play behavior in brown bears, Ursus arctos. Evol. Ecol. Res. 6, 89–102 [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pellis SM, Mckenna M. 1992. Intrinsic and extrinsic influences on play fighting in rats: effects of dominance, partner playfulness, temperament and neonatal exposure to testosterone propionate. Behav. Brain Res. 50, 135–145 10.1016/S0166-4328(05)80295-5 (doi:10.1016/S0166-4328(05)80295-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Armitage KB. 1991. Social and population dynamics of yellow-bellied marmots: results from long-term research. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 22, 379–407 10.1146/annurev.es.22.110191.002115 (doi:10.1146/annurev.es.22.110191.002115) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bekoff M. 1977. Mammalian dispersal and the ontogeny of individual behavioral phenotypes. Am. Nat. 111, 715–732 10.1086/283201 (doi:10.1086/283201) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blumstein DT, Wey TW, Tang K. 2009. A test of the social cohesion hypothesis: interactive female marmots remain at home. Proc. R. Soc. B 276, 3007–3012 10.1098/rspb.2009.0703 (doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0703) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Armitage KB, Van Vuren DH, Ozgul A, Oli MK. 2011. Proximate causes of natal dispersal in female yellow-bellied marmots, Marmota flaviventris. Ecology 92, 218–227 10.1890/10-0109.1 (doi:10.1890/10-0109.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Armitage KB. 2003. Reproductive competition in female yellow-bellied marmots. In Adaptive strategies and diversity in marmots (eds Ramousse R, Allaine D, Le Berre M.), pp. 133–142 Lyon, France: International Marmot Network [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blumstein DT. 2013. Yellow-bellied marmots: insights from an emergent view of sociality. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B (doi:10.1098/rstb.2012.0349) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maynard Smith J, Price GR. 1973. The logic of animal conflict. Nature 246, 15–18 10.1038/246015a0 (doi:10.1038/246015a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Byers JA. 1977. Terrain preferences in the play behavior of Siberian ibex kids (Capra ibex sibirica). Z. Tierpsychol. 45, 199–209 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pellis SM, Pellis VC, Kolb B. 1992. Neonatal testosterone augmentation increases juvenile play fighting but does not influence the adult dominance relationships of male rats. Aggress. Behav. 18, 437–447 (doi:10.1002/1098-2337(1992)18:6<437::AID-AB2480180606>3.0.CO;2-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Monclús R, Cook T, Blumstein DT. 2012. Masculinized female yellow-bellied marmots initiate more social interactions. Biol. Lett. 8, 208–210 10.1098/rsbl.2011.0754 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0754) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arnold AP, Breedlove SM. 1985. Organizational and activational effects of sex steroids on brain and behavior: a reanalysis. Horm. Behav. 19, 469–498 10.1016/0018-506X(85)90042-X (doi:10.1016/0018-506X(85)90042-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dloniak SM, French JA, Holekamp KE. 2006. Rank-related maternal effects of androgens on behaviour in wild spotted hyaenas. Nature 440, 1190–1193 10.1038/nature04540 (doi:10.1038/nature04540) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]