Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To determine perceived quality of life in a diverse population of elderly adults with late-life disability.

DESIGN

Qualitative cross-sectional study.

SETTING

Community-dwelling participants were recruited from San Francisco’s On Lok Lifeways program, the first Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly. On Lok enrollees meet Medicaid criteria for nursing home placement.

PARTICIPANTS

Sixty-two elderly adults with a mean age of 78 and a mean 2.4 activity of daily living dependencies and 6.6 instrumental activity of daily living dependencies were interviewed. Respondents were 63% female, 24% white, 19% black, 18% Latino, 32% Chinese American, and 6% other race.

MEASUREMENTS

Elderly adults who scored higher than 17 points on the Mini-Mental State Examination were interviewed. Interviews were conducted in English, Spanish, and Cantonese. Respondents were asked to rate their overall quality of life on a 5-point scale. Open-ended questions explored positive and negative aspects of participants’ daily experiences. Interviews were analyzed using modified grounded theory and digital coding software.

RESULTS

Eighty-seven percent of respondents rated their quality of life in the middle range of the quality-of-life spectrum (fair to very good). Themes were similar across ethnic groups. Most themes could be grouped into four domains that dependent elderly adults considered important to their quality of life: physical (e.g., pain), psychological (e.g., depression), spiritual or religious (e.g., religious coping), and social (e.g., life-space). Dignity and a sense of control were identified as themes that are the most closely tied to overall quality of life.

CONCLUSION

Factors that influence quality of life in late-life disability were similar across ethnic groups. As the number of elderly adults from diverse backgrounds with late life disability increases in the United States, interventions should be targeted to maximize daily sense of control and dignity.

Keywords: ethnicity, quality of life, disability

It is likely that quality of life assessments will be critical in helping the healthcare system address the needs of a rapidly growing and diversifying geriatric population, especially those living with late-life disability.1,2 Eighteen million people aged 65 and older in the United States are currently living with a disability.2 Late life is a term used to describe a period near the end of life (typically ≥ 65) and distinguishes this population from people who develop disability earlier in life.3,4 As people move into late life, their level of disability increases dramatically.5,6 In one study of individuals aged 85 to 89 and 90 and older, only 15% and 3%, respectively, were able to perform all activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) independently in their last year of life.7 In general, many older adults are living with disability for years before death, and this proportion rises dramatically during the last years of life.8

Despite the growing population of elderly adults with late-life disability, little is known about their experience or quality of life. Most nondisabled people fear living in a state of disability before death and are potentially unprepared to manage declining function and dependence.9,10 Previous research on quality of life in the general population has assumed that quality of life decreases as people age and become more disabled,11 but the best source for information about quality of life is not the projection of healthy individuals about quality of life in hypothetical states of disability but the perspectives of the elderly adults who are living with late-life disability. This research is lacking.

To address the lack of information about this population in quality-of-life research, a qualitative study was conducted to characterize the factors that contribute to quality of life in a diverse population of elderly adults with late-life disability. It was decided to study this question in a diverse population because culture can greatly influence many of the factors that influence quality of life, and it was desired to examine a range of perspectives that reflects the diversification of the elderly population in the United States. If the quality of life that elderly adults with late life disability experience is better understood, it will be possible to develop better assessment tools to measure quality of life accurately in the future and, as a result, to target interventions to improve quality of life for a growing population of elderly adults with late-life disability and significant health needs.

METHODS

Study Design and Sample

A qualitative study was conducted using semistructured in-person interviews with patients of On Lok. On Lok is a community-based Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE) in San Francisco, San Jose, and Fremont, California. Elderly adults live an average of 4.5 years from the time of enrollment and are eligible for long-term nursing home care based on their level of disability.12 Participants were selected from the San Francisco centers. There are eight On Lok centers throughout San Francisco offering a range of services including primary medical care, exercise classes and physical therapy, meals, and community programs. The patient’s primary contact is a case manager, usually a master’s level social worker. The organization’s mission is to serve elderly adults in their familiar communities. Thus centers across the city serve elderly adults of specific ethnicities living in the immediate neighborhoods. Although each On Lok center serves participants of diverse backgrounds, some serve specific populations, such as the Spanish-speaking Latino population or the Cantonese-speaking Chinese population. All available participants at six of eight sites were identified. Individuals with a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score less than 17 were excluded, as were those whose primary language was not English, Spanish, or Cantonese.

Once eligible participants were identified, case managers and center managers helped to facilitate meetings with participants, and interviews were scheduled based on participant availability and interviewer availability. On Lok staff provided data on participants’ independence in ADLs (bathing, dressing, hygiene, toileting, transferring, feeding) and IADLs (meal preparation, shopping, housework, laundry, managing money, taking medication, transportation). Participants who required any level of assistance in one activity were defined as dependent in that activity. Interviewers were not employees of On Lok, and On Lok staff did not attend the interview sessions. Each interviewer was a native speaker in the primary language of the participant. To protect confidentiality, participant ages included alongside the quotes in this text were slightly altered.

Data Collection

Sixty-two older adults were interviewed in English, Spanish, and Cantonese using a common interview guide. The guide was modified iteratively as more interviews were completed to clarify topics of interest. Interviewers asked participants to rate their quality of life on a 5-point scale and to describe the reasons for their answer. The interviewers asked open-ended questions about participants’ daily lives, including positive and negative aspects and descriptions of daily activities. Probes about dependence and disability were used (see Online Appendix for interview guide). The interview guide was translated from English into Spanish and Cantonese and reverse translated to ensure accuracy. Where words or concepts did not translate well from English to Spanish or Cantonese, a word or concept that worked well in Spanish and Cantonese was located and translated back into English.

Data Analysis

Interviews were recorded, translated, and transcribed. A professional transcriptionist transcribed interviews in English. A bilingual research assistant translated interviews in Spanish and Cantonese into English at the time of transcription. All interviews were analyzed in English using Hyperresearch software (ResearchWare, Inc., Randolph, MA) and following standard grounded theory principles.13,14 Data were collected and analyzed using a system of constant comparative analysis in which data were reviewed iteratively to identify new themes. The multidisciplinary research team, including representatives from medicine, nursing, ethics, geriatrics, psychology, and the law, coded several partial transcripts to develop a common code book. A single researcher then coded the remainder of the transcripts. A second researcher repeated coding of 25% of the transcripts and greater than 80% concordance was achieved. Throughout the coding process, new codes were added as new themes emerged, and prior transcripts were recoded to reflect the new coding scheme. When no new themes emerged, saturation was reached, and no further interviews were conducted. Themes were organized into a conceptual model of quality of life in late-life disability.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Participants

Characteristics of the 62 participants are given in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 78; 63% were women. The self-identified race or ethnicity of participants was 15 (24%) whites, 12 (19%) blacks, 11 (18%) Latinos, 20 (32%) Asian (Chinese), and four (6%) another race or ethnicity. On average, participants needed assistance from other persons in 2.4 of 6 ADLs and 6.6 out of 7 IADLs.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | Total (N = 62) | Black (n = 12) | Chinese American (n = 20) | White (n = 15) | Latino (n = 11) | Other (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 78.3 ± 9.6 | 74.3 ± 13.4 | 82.3 ± 5.6 | 75.1 ± 10.3 | 76.0 ± 8.8 | 85.3 ± 8.3 |

| Female, n (%) | 39 (63) | 9 (75) | 10 (50) | 8 (53) | 8 (73) | 4 (100) |

| Religious affiliation, n (%) | ||||||

| Buddhist | 5 (8) | 0 | 3 (15) | 2 (13) | 0 | 0 |

| Catholic | 14 (22) | 1 (8) | 1 (5) | 4 (26) | 7 (64) | 1 (25) |

| None | 18 (29) | 3 (24) | 10 (50) | 4 (26) | 1 (9) | 0 |

| Protestant | 19 (31) | 7 (60) | 3 (15) | 5 (33) | 2 (18) | 2 (50) |

| Other or unspecified | 6 (10) | 1 (8) | 3 (15) | 0 | 1 (9) | 1 (25) |

| Education (years), n (%) | ||||||

| None (0) | 4 (6) | 0 | 4 (20) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Elementary (1–8) | 24 (39) | 2 (17) | 10 (50) | 1 (7) | 9 (82) | 2 (50) |

| High school (9–12) | 19 (31) | 8 (66) | 5 (25) | 4 (26) | 2 (18) | 0 |

| College (13–18) | 15 (24) | 2 (17) | 1 (5) | 10 (67) | 0 | 2 (50) |

| Number of ADL dependencies, n (%) | ||||||

| 0 | 8 (13) | 2 (17) | 1 (5) | 3 (20) | 2 (18) | 0 |

| 1 | 15 (24) | 0 | 7 (35) | 5 (33) | 2 (18) | 1 (25) |

| 2 | 10 (16) | 2 (17) | 4 (20) | 1 (7) | 2 (18) | 1 (25) |

| 3 | 10 (16) | 5 (42) | 3 (15) | 0 | 2 (18) | 0 |

| 4 | 5 (8) | 0 | 2 (10) | 2 (13) | 1 (9) | 0 |

| 5 | 8 (13) | 1 (8) | 3 (15) | 5 (33) | 0 | 1 (25) |

| 6 | 3 (5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (7) | 2 (18) | 0 |

| Number of ADL dependencies, mean ± SD | 2.4 ± 1.8 | 2.4 ± 1.5 | 2.4 ± 1.6 | 2.4 ± 2.2 | 2.5 ± 2.1 | 2.7 ± 2.1 |

| Number of IADL dependencies, n (%) | ||||||

| <5 | 2 (4) | 1 (8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (9) | 0 |

| 5 | 2 (3) | 0 | 1 (5) | 1 (7) | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 13 (21) | 0 | 1 (5) | 5 (33) | 7 (64) | 0 |

| 7 | 42 (28) | 9 (75) | 18 (90) | 9 (60) | 3 (27) | 3 (75) |

| Number of IADL dependencies, mean ± SD | 6.6 ± 0.8 | 6.6 ± 1.3 | 6.9 ± 0.5 | 6.5 ± 0.6 | 6.1 ± 0.8 | 7 ± 0 |

| Mini Mental State Examination score, n (%) | ||||||

| <22 | 7 (12) | 0 | 4 (20) | 2 (14) | 0 | 1 (25) |

| 22 | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (9) | 0 |

| 23 | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 24 | 7 (11) | 1 (8) | 3 (15) | 1 (7) | 2 (18) | 0 |

| 25 | 3 (5) | 0 | 0 | 1 (7) | 2 (18) | 0 |

| 26 | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (50) |

| 27 | 8 (13) | 2 (17) | 5 (25) | 1 (7) | 0 | 0 |

| 28 | 6 (10) | 1 (8) | 2 (10) | 2 (13) | 1 (9) | 0 |

| 29 | 10 (16) | 1 (8) | 1 (5) | 6 (40) | 2 (18) | 0 |

| 30 | 3 (5) | 0 | 3 (15) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mini Mental State Examination score, mean ± SD | 26.0 ± 3.2 | 27 ± 1.9 | 25.5 ± 3.7 | 26.7 ± 3.2 | 25.8 ± 2.6 | 24.3 ± 2.9 |

| Quality of life, n (%) | ||||||

| Excellent | 6 (10) | 0 | 1 (5) | 3 (20) | 2 (18) | 0 |

| Very good | 17 (27) | 4 (33) | 4 (20) | 6 (40) | 2 (18) | 1 (25) |

| Good | 24 (39) | 5 (42) | 7 (25) | 5 (33) | 4 (36) | 3 (75) |

| Fair | 13 (21) | 3 (25) | 8 (40) | 0 | 2 (18) | 0 |

| Poor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Quality of life score, mean ± SD | 3.3 ± 0.9 | 3.1 ± 1.8 | 2.9 ± 0.9 | 3.9 ± 0.8 | 3.4 ± 1.1 | 3.2 ± 0.5 |

| Birthplace, n (%) | ||||||

| Outside United States | 35 (56) | 1 (8) | 18 (90) | 4 (27) | 10 (93) | 2 (50) |

| United States | 26 (42) | 10 (84) | 2 (10) | 11 (73) | 1 (7) | 2 (50) |

| Unknown | 1 (2) | 1 (8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

SD = standard deviation; ADL = activity of daily living; IADL = instrumental activity of daily living.

Overall Quality of Life

When asked to rate their overall quality of life, 54 (87%) responded in the middle ranges of the scale (fair, good, or very good). When asked “why,” participants’ responses focused on maintaining their current level of functioning, participating in activities that they enjoyed, having positive social relationships, and having a sense of peace that their needs were taken care of. One participant responded:

Because I have everything I need. I have a roof over my head, I have food on the table. All my physical and emotional needs are met. I have all my faculties, I can go for a walk, I have my physical health. I got music appreciation tomorrow, I take tai chi. (white woman, aged 62)

Overall quality-of-life assessments were often positive even after participants described at length things that made their lives uncomfortable or difficult. They stressed having a balance of positive and negative factors, leading to responses in the middle ranges of the quality-of-life scale.

Participants also frequently compared themselves with other elderly adults, stating, “I don’t feel bitter because I am in a wheelchair. I don’t feel conflicted, I feel good. I am at peace and I think there are other people who are worse than me” (Latina woman, aged 66). These participants felt that things could get a lot worse than they were and saw their quality of life on a continuum with the elderly adults living around them.

Thematic Analysis Organized in a Conceptual Model

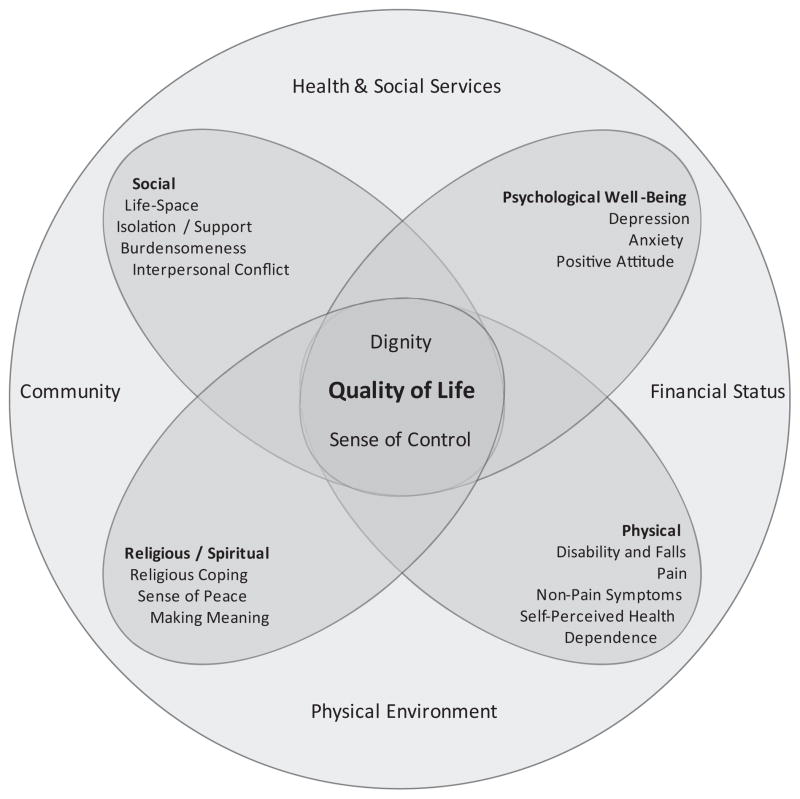

Four broad domains that contribute to quality of life in late-life disability were identified: physical, psychological, social, and spiritual or religious (Figure 1). Each domain consisted of factors that directly contributed to quality of life (e.g., pain and falls in the physical domain). The themes of dignity and sense of control were identified throughout the interviews as central factors most closely related to overall quality of life in all domains. Respondents described the physical environment, available health and social services, and their financial status as contextual features with a more-remote influence on quality-of-life domains. The domains, central factors, and contextual features affecting quality of life are described in detail in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Model of quality of life in late-life disability. This model represents the domains, functions, central factors, and contextual features of quality of life for people with late-life disability developed from this study. The domains are broad categories that contribute to overall quality of life. These domains overlap, with many experiences crossing domains, as represented by the overlapping petals. Within each petal are the specific factors that contribute to quality of life. These factors can have negative and positive effect on quality of life. The central factors dignity and sense of control are most closely related to overall quality of life. When people have a sense of control and dignity, their overall quality of life is better, and the effect of negative factors is lessened. The model also demonstrates that one’s quality of life has to be understood in the context of community, financial status, physical environment, and health and social services available to the individual.

Table 2.

Summary of Findings: Quality of Life in Late-Life Disability

| Domain | Definition | Quotation |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | ||

| Disability and falls | Physical or cognitive disability, loss of ability to do daily tasks or activities, and experiences of falls or fear of falling | “It’s like being in prison. […] If there are any parties or outside celebrations such as weddings, we don’t dare go [because we are afraid of falling].” (Chinese-American man, aged 81) |

| Dependence | Relying on others for assistance with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living | “It’s kind of hard because I used to jump up and run to Safeway, but right now, I have to wait for somebody to do it for me. I’m not—just not able to do it. […] It’s rough, and when you’re not used to it, it’s very hard, but when you can’t do any better, you just have to accept it.” (black woman, aged 78) |

| Adaptation | Assistive devices, medications, or behavior modifications used to overcome limitations caused by physical disability | “I have trouble with my shoulder and with my knee. That’s why I was getting therapy today, but it feels much better after I got the therapy.” (black woman) |

| Pain | The experience of chronic pain and its sources and effect on daily life | “[I hope] to be healthy again, to have a stronger body, no pain. If I have just a little bit, I can take care of that pain. But with arthritis it’s terrible. I always fall down.” (Filipina white woman, aged 84) |

| Non-pain symptoms | Bothersome symptoms not related to pain (e.g., constipation, shortness of breath, fatigue) | “I don’t walk because of the lack of energy. I can’t move— it’s tiring.” (Chinese man, aged 77) |

| Self-perceived health | Concerns about specific diseases, worsening health and overall health status | “I would like to continue the mode as it is; however, I have to accept the reality may be my health. Right now, it’s really quite good, but that could go down.” (white woman, aged 88) |

| Social | ||

| Life-space15 | The size of one’s physical space that one can move through freely without assistance | “When you go out on your own, you check things out. […]Now I cannot go because I’m by myself now. You’re afraid to take the bus too. Before [I could] take the bus to go out, but last year since the fall until now, [I’m] too afraid to go out on my own.”(Chinese woman, aged 80) |

| Isolation and support | Relationships with family, friends, neighbors, caregivers that provide emotional support and the effect of the absence of these relationships | “Very lonely. [There’s] no one to talk to. […] An elderly person is at home by himself or herself.” “When my sons and grandkids have time on the weekends, they will take me out to lunch. They don’t want me to be alone at home.” (Chinese woman, aged 91) |

| Burdensomeness | Fears of causing financial or physical hardship to family, friends, or society | “They still mind, you know, even if they don’t say it. They still mind.” (Filipina white woman, aged 85) |

| Interpersonal conflict | Difficulty talking with providers or family members about concerns, symptoms, needs, or wishes | “At home, it is very difficult to talk with my son. When I cannot hear him and ask him to tell me again, he gets mad and very mean.” (Chinese woman, aged 82) |

| Psychological well-being | ||

| Depression | Symptoms of anhedonia, depressed mood, hopelessness | “Now that I’m old and cannot walk and stuff, there’s not much I want to do.” (Chinese woman, aged 75) |

| Anxiety | Overall worry about the future, daily activities, generalized fear | “I don’t want to die being helpless. Right now I’m helpless enough.” (white man, aged 76) |

| Positive attitude | Maintaining a happy or contented mood | “I’m doing pretty well. I mean I live at home now all by myself because my wife died. […] I stayed in the apartment and I have a good outlook, which is good. I don’t know why [chuckle], but I have a good outlook, so that helps. It helps a lot.” (white man, aged 58) |

| Spiritual and religious | ||

| Religious coping | Religious beliefs that assist one in accepting disability or psychological distress | “My belief in God is that He’s taking care of me. Can’t nobody else do nothing for me but Him. I know that, and that’s who I rely on for everything.” (black man, aged 61) |

| Sense of peace | Acceptance of the current state of life, regardless of level of disability or dependence | “At this age, I don’t really hope for much. Just do what’s right on a day, eat what’s right for me, sleep well, and I’m satisfied.” (Chinese woman, aged 83) |

| Meaning making | Participating in activities, hobbies or social groups that create a sense of purpose or fulfillment | “Painting’s been a Godsend. Where I used to live, they had a wonderful art teacher, and one of my paintings was shown, so I feel I’m really encouraged.” (white woman, aged 79) |

| Central factors | ||

| Sense of control | Having a sense of power or control over what happens in one’s life; often includes relational autonomy or having control through a relationship or dependency on someone else to do what the person wishes | “Just because I had a stroke doesn’t make me dead. What I ask is this: Let me decide what I want to do with the rest of my life on my own. Don’t help me, and don’t make the decisions for me.” (black man, aged 67) |

| Dignity | Having a sense of one’s identity and place in society that those around one value and respect | “It’s unfortunate that a lot of your family or other people feel that, once you’re old, you don’t know anything anymore and you’re just kind of in the way.” (white woman, aged 84) |

| Contextual features | ||

| Health and social services | Agencies providing support for health care, transportation, food, exercise, social activities, caregivers | “I have built a certain level of trust here, including with the staff that takes care of us. So that is a benefit to us because we need that. […] The other thing is that, on the days that I come here, if I have a clinical or medical need, I can see the doctor.” (Latino man, aged 82) |

| Physical environment | The surroundings, including housing, neighborhood, cleanliness, safety, disturbances | “I had to get out of that [hotel] because they got bed bugs in the walls and you can watch them crawling down the walls, and the place I’m in right now, I killed two of them the other day.” (white woman, aged 75) |

| Financial status | Ability to meet basic needs with income and savings | “It’s hard to save. You have to pay for your food, rent, so it’s hard to have any money left over to save at the end.” (Latina woman, aged 68) |

| Community | A sense of belonging to a social group with common features | “We [Chinese people] depend on our own. We depend on ourselves.” (Chinese man, aged 89) |

Analysis According to Ethnicity

Commonalities between ethnic groups far exceeded any differences. When examined quantitatively, there were no differences in response to the question about overall quality of life in this sample, although there were two factors with some difference between groups: religious coping and depression. Although participants from all ethnic groups described the importance of the spiritual domain in quality of life, Latino and black participants most frequently and emphatically identified religious beliefs as being important to quality of life and their ability to manage disability and dependence. Although the study did not formally evaluate for depression, Chinese participants described symptoms of anhedonia or hopelessness more often than other ethnic groups, using phrases such as “not much I want to do” (Chinese woman, aged 75).

Interdependence of Domains

The domains described in Table 2 express the parts of participants’ lives that contribute to quality of life, but these domains are not completely separate from each other. Throughout the data, it was clear that the factors within each domain were interdependent. As the quotes in Table 2 illustrate, pain and physical disability directly contributed to life-space, which in turn affected psychological wellbeing. There was a strong emphasis placed on relationships in all of the interviews and the physical and emotional support that these relationships provided. Relationships frequently defined a participant’s life-space or the physical domain they could inhabit in the world and the freedom with which they were able to move through this space. Positive attitude was also often linked to emotional support, as well as religious belief. Thus, there was significant overlap of concepts or interdependence within the four domains and in their effect on quality of life.

Central Factors: Sense of Control and Dignity

Having a sense of control in some aspect of daily life and feeling respected as a valued individual (dignity) had the largest influence on overall quality of life, based on qualitative comparisons of statements made describing quality of life and contributing elements. These central factors provided balance, altering the weight that dependence and disability had in their overall quality of life. Some participants expressed the desire to have a sense of control as skepticism of the level of dependence that physicians or care providers assigned to them. Participants stated “they are afraid I’ll fall” (Filipina woman, aged 78) and “they try to help me for no reason” (Chinese man, aged 94); “I don’t need it” (Chinese man, aged 75). Nevertheless, most participants found a level of acceptance and ways to maintain a sense of control in some aspects of their life, such as continuing hobbies or activities that brought them joy.

Dignity was similarly central to quality of life. Several participants described feeling in the way or unnoticed by those around them: “Well, you know, sometimes it feels like you’re a lump” (white woman, aged 58), yet this participant, who became blind after a stroke, rated her quality of life as very good and described many instances of positive attitude and adaptation to her disabilities, such as making coffee and maintaining personal hygiene. These activities helped her reestablish her dignity in the setting of greater dependence on others. Dignity played a larger role in her self-perceived quality of life than her experience of dependence. This example illustrates the constant overlap of domains and self reevaluation that participants described as part of their overall quality of life as they struggled with late-life disability.

Contextual Features

There were four contextual features raised in the interviews that did not directly affect quality of life but that were important in understanding the overall environment of the participants and what was important to them (Table 2, Figure 1). Many described being able to develop a sense of peace, form close relationships, and access health care and rehabilitation through the services provided at On Lok and other agencies such as Meals on Wheels. Although On Lok itself was not a part of quality of life, it provided many of the health and social services that contribute to quality of life. A related contextual feature was the sense of belonging to a community that most participants shared, or not belonging for a few. For most, this community was a cultural community, for some it was a religious community. In addition, community shaped participants’ quality of life by providing them with a group of peers with whom they could compare themselves. Some participants were disparaging of others and defined their own quality of life as very good or better than that of those around them. The physical environment, including stairs, cleanliness, and neighbors, contributed to life-space, psychological well-being, and support or isolation for many participants. Finally, many of the participants were from low-income backgrounds and did not have many financial resources other than Social Security. Although financial status was not as central as other themes, it affected their concerns about being a burden, health status, and dependence.

DISCUSSION

The vast majority of participants rated their overall quality of life in the middle of the scale, despite significant ADL and IADL dependency, physical and emotional suffering, and limited life-space. Participants described a range of factors in four domains (physical, psychological, social, spiritual) that contributed to this level of quality of life. These domains are consistent with the biopsychosocial model and other quality-of-life frameworks,16–18 although some factors were unique to this study population. Dignity and a sense of control were central factors that had the strongest effect on quality of life by allowing participants to build autonomy and self-worth. Adaptations to maintain the current level of functionality, a positive attitude, and positive social relationships and emotional support were factors that contributed to a higher quality of life in the setting of disability. Participants also described a process of adapting to disability by first struggling with loss of independence and then achieving a sense of peace or acceptance of their current state of disability. These findings were reassuring that a high quality of life is possible in late-life disability. Prominent negative factors included threats to dignity and sense of control, experiences of pain, and depressive symptoms. Balancing these positive and negative contributions, quality of life for most participants was rated in the middle range of the spectrum—“I’m doing OK,” as one participant stated (white woman, aged 61).

This study identified several factors that contribute to quality of life in late-life disability not highlighted in most quality-of-life assessment tools (e.g., dignity, sense of control, sense of peace, and positive attitude). In addition, elderly adults with disability may have different expectations and norms for their lives than the general population.11 Some recent studies have attempted to develop quality-of-life instruments specific to elderly adults, although not specifically for elderly adults with late-life disability.19,20 The Control, Autonomy, Self-realization, Pleasure quality of life measure (CASP-19) identified core areas specific to elderly adults.20 Studies using CASP-19 continue to show declining quality of life as disability increases.21–23 The Older People’s Quality of Life Questionnaire attempts to address a more-diverse sample but has yet to be studied in depth.19,24 Other measures have accounted for ethnic diversity and frailty but, in doing so, have focused on specific health-related outcomes and quality of life rather than on an overall measure of quality of life that could locate disability and deteriorating health in a broader, more-meaningful context.25 The current study demonstrates that a measure of quality of life for elderly adults should include the elements of sense of peace, dignity, and positive attitude in addition to the elements included in previous scores. New tools need to be developed and tested to assess the quality of life of diverse elderly adults with late-life disability more accurately.

No previous studies have examined quality of life in late-life disability for a diverse group of elderly adults. Quality of life was assessed in several cultural groups and languages, and not many differences were found between them, suggesting a high level of concordance in community-dwelling elderly adults with late-life disability and internal validity within the study. Although overall quality of life and quality-of-life domains may not vary between racial or ethnic groups of similar socioeconomic background, methods of coping or achieving acceptance and the weight placed on different factors may differ, as the role that religious coping played for some participants suggested. There were also demographic differences between the racial and ethnic groups, such as level of education and religious affiliation, that could not be further analyzed with the small sample size and qualitative methodology. Differences in the factors contributing to quality of life between ethnic groups may be better assessed in a quantitative study with representative samples and in which more-complex demographic analysis can be performed. Further research is needed to better understand how disabled elderly adults from different cultural backgrounds manage increasing disability and maintain a high quality of life.

The findings of the current study suggest there may be a shift in self-assessment of quality of life as disability increases. As elderly adults are faced with greater disability and decline in function, they become less focused on what they cannot do and shift to assessing quality of life by what they can still do. Many of the participants described a process of accepting disability that was challenging and painful at times but allowed them to have a sense of peace and security. Elderly adults cope with their disability by developing physical adaptations, engaging in hobbies and social activities, and embracing their religious faith. They emphasize maintaining good relationships with family and friends rather than attaining social status or financial gains (as described in quality-of-life assessments of younger populations). These quality-of-life factors have been previously described in studies of elderly adults but not in those with the level of disability and dependence that the current study population experienced.18 For this population, because they were dependent on others for much of their daily lives, relationships played a larger role in quality of life than for elderly adults who were living independently.

It is important to consider the limitations of this study. The sample of community-dwelling elderly adults with late-life disability was specific in that all participants were enrolled in a PACE program, which provided significant support for health care, physical needs, and social engagement to participants, all of which were elements contributing to quality of life. Additionally, the definition of late-life was cross-sectional and did not allow for an assessment of prognosis or proximity to the end of life in relation to current quality of life. As with all qualitative studies, this study was not representative of larger populations of elderly adults with late-life disability or even those in PACE programs, especially because the participants were those willing and able to participate. The interviews were conducted at On Lok, which may have created bias for participants to speak positively about their experience there, despite being told that the interviews were confidential. The study included participants from multiple ethnic backgrounds, and given the limited sample size within groups, comparisons according to other social and demographic factors such as age and religion were not possible. To have data that could be analyzed readily, participants with significant cognitive impairments and low MMSE scores were excluded. Alternatively, based on work demonstrating that quality of life in individuals with dementia can be assessed with greater ability than previously realized, participants with MMSE scores as low as 18 were interviewed.26 Further research is needed to test and refine the proposed model of quality of life in other populations of elderly adults living with disability—those not enrolled in PACE, those with more-severe cognitive impairment, and those living in nursing homes. Finally, approximately half of the interviews were conducted in a language other than English and then translated by the interviewers. This may have led to biases in the English transcripts that it was not possible to account for in the final analysis, although many of the words used for themes and codes, such as “quality of life” and “well-being,” were discussed, and consensus was achieved on definitions before beginning interviews, decreasing the potential for this bias.

Elderly adults with significant late-life disability can achieve high quality of life despite significant physical disability and dependence on others for assistance with daily activities. Quality of life for these elderly adults is most closely related to dignity and a sense of control in daily aspects of their lives. As the number of elderly adults with late life disability increases in the United States, interventions and services that can be targeted to maximize the benefit to these individuals need to be developed.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Smith was supported by Grant P30-AG15272 of the Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research program funded by the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. Additional support provided by the National Center for Research Resources UCSF-CTSI (UL1 RR024131), Atlantic Philanthropies, the Society of General Internal Medicine, the John A. Hartford Foundation, and the Association of Specialty Professors. An early version of this paper was presented in abstract form at the 2011 Annual Meetings of the American Geriatrics Society, National Harbor, Maryland, and the Society of General Internal Medicine, Phoenix, Arizona.

Sponsor’s Role: The sponsors had no role in the design, methods, participant recruitment, data collections, analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the study design, acquisition of participants, analysis of data, and preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Yeo G. How will the U.S. healthcare system meet the challenge of the ethnogeriatric imperative? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1278–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. The Next Four Decades: The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050 Population, Estimates and Projections. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiao C, Weng LJ, Botticello AL. Economic strain and well-being in late life: Findings from an 18-year population-based longitudinal study of older Taiwanese adults. J Public Health (Oxf) 2011 Sep 12; doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr069. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thorpe RJ, Jr, Koster A, Kritchevsky SB, et al. Race, socioeconomic resources, and late-life mobility and decline: Findings from the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66A:1114–1123. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lunney JR, Lynn J, Foley DJ, et al. Patterns of functional decline at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289:2387–2392. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.18.2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Covinsky KE, Eng C, Lui LY, et al. The last 2 years of life: Functional trajectories of frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:492–498. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao J, Barclay S, Farquhar M, et al. The oldest old in the last year of life: Population-based findings from Cambridge city over-75s cohort study participants aged 85 and older at death. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, et al. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1173–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hildon Z, Smith G, Netuveli G, et al. Understanding adversity and resilience at older ages. Sociol Health Illn. 2008;30:726–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angus J, Reeve P. A threat to “aging well” in the 21st century. J Appl Gerontol. 2006;25:137–152. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Netuveli G, Blane D. Quality of life in older ages. Br Med Bull. 2008;85:113–126. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldn003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eng C, Pedulla J, Eleazer G, et al. Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE): An innovative model of integrated geriatric care and financing. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:223–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb04513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glaser B, Strauss A. Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967. Discovery of Grounded Theory. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyle PA, Buchman AS, Barnes L, et al. Association between life space and risk of mortality in advanced age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1925–1930. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart AL, King AC. Conceptualizing and measuring quality of life in older populations. In: Abeles RP, Gift HC, Ory MG, editors. Aging and Quality of Life. New York: Springer Publishing Co; 1994. pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puts MT, Shekary N, Widdershoven G, et al. What does quality of life mean to older frail and non-frail community-dwelling adults in the Netherlands? Qual Life Res. 2007;16:263–277. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowling A. The psychometric properties of the older people’s quality of life questionnaire, compared with the CASP-19 and the WHOQOL-OLD. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res. 2009;2009:298950. doi: 10.1155/2009/298950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hyde M, Wiggins RD, Higgs P, et al. A measure of quality of life in early old age: The theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19) Aging Ment Health. 2003;7:186–194. doi: 10.1080/1360786031000101157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blane D, Netuveli G, Montgomery SM. Quality of life, health and physiological status and change at older ages. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1579–1587. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Netuveli G, Wiggins RD, Hildon Z, et al. Quality of life at older ages: Evidence from the English longitudinal study of aging (wave 1) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:357–363. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.040071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webb E, Blane D, McMunn A, et al. Proximal predictors of change in quality of life at older ages. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:542–547. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.101758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bowling A, Stenner P. Which measure of quality of life performs best in older age? A comparison of the OPQOL, CASP-19 and WHOQOL-OLD. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:273–280. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.087668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stewart AL, Napoles-Springer A. Health-related quality-of-life assessments in diverse population groups in the United States. Med Care. 2000;9(Suppl):II102–II124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brod M, Stewart AL, Sands L, et al. Conceptualization and measurement of quality of life in dementia: The dementia quality of life instrument (DQoL) Gerontologist. 1999;39:25–35. doi: 10.1093/geront/39.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]