Abstract

Although 17β-Estradiol (E2) improves cognitive performance of aged female mice, its mnemonic effects when administered post-training to aged male mice have not been examined. E2 (10 µg, SC) or oil vehicle was administered to intact, 24-month-old female or male congenic (primarily C57BL/6 background) mice immediately after training in the inhibitory avoidance or water maze tasks. Following behavioral testing, effects of 1 or 24 h of E2 exposure on hippocampal levels of E2 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) were examined. Female and male mice administered E2 showed significantly better performance in the inhibitory avoidance task than did vehicle-administered mice. When tested 24 h after training, mice that received E2 had significantly longer latencies to cross-over to the shock-associated side of the chamber than did vehicle-administered mice. Female or male mice administered E2 showed significantly better performance in the reference memory aspect of the spatial water maze task. When tested 30 min after training, mice administered E2 had shorter latencies to, and spent longer swimming in, the quadrant that the hidden platform had previously been located in. E2 administration produced physiological levels of E2 in the hippocampus 1 and 24 h after E2. BDNF levels in the hippocampus were decreased following 1 h of E2 exposure compared to vehicle. These findings suggest that E2 to female and male mice may overcome age-related deficits in reference memory in an emotional or spatial learning task.

Keywords: Estrogen, Aging, Memory, Hippocampus

1. Introduction

17β-estradiol (E2) can enhance cognitive performance in a number of populations. Although hormone therapy has recently come under fire [82], E2 may have some beneficial effects on cognitive function. E2 replacement attenuates impaired cognitive performance associated with menopause [77,80]. Women receiving E2 following menopause demonstrate enhanced verbal, short-term, and long-term memory, as well as logical reasoning, compared to women not receiving E2 replacement [76,78,79]. These improvements appear to occur as a function of age. E2 to older, physiologically-menopausal women produces greater improvement in verbal memory compared to that seen in younger, surgically-menopausal women with fewer verbal memory deficits [6,76]. E2 also enhances cognition in a population with more profound cognitive deficits. Women with Alzheimer’s disease receiving E2-replacement therapy showed significant improvement on a number of cognitive measures compared to age-matched controls [1,62]. However, not all studies find beneficial effects of E2. Hormone therapy that results in very high or very low levels of E2 produces impaired spatial ability, whereas mid-level E2 is associated with improvement on tests of verbal, visual, and semantic memory compared to that of post-menopausal women given placebo [1,34,45]. Thus, beneficial effects of E2 among women seem to be most readily observed in aging individuals that receive replacement with moderate E2 concentrations.

E2 may also have beneficial effects among men for enhanced cognitive performance. Young men with high levels of E2 performed better on two measures of visual memory than did men with normal but lower E2 levels [38]. Among older men, low levels of E2 were associated with decreased cognitive function [75]. Further, treatment of elderly men with testosterone enhanced spatial and verbal memory in association with increased testosterone and E2 levels [9]. However, it should be noted that other studies have reported either no relationship [11,18,40] or a negative association between E2 and cognition among men [15,37]. Thus, the effects of E2 to modulate cognition are not well-understood and require further investigation.

Several factors may influence E2’s effects on cognitive performance in animal models. Among young rodents, variable performance during behavioral estrus (when endogenous E2 levels are higher relative to estrus) is associated with E2 concentrations and task demand [4,14, 26,31,41,83,84,95]. Findings from extirpation and E2 replacement studies in younger rodents also suggest that better performance is related to moderate E2 levels and task difficulty [5,10,13,21,24,25,27,30,33,35,44,49,63–65, 72,74]. In support, previous data have shown that proestrous rats exhibit increased motor behavior compared to rats in other phases of the estrous cycle [2,29]. As such, proestrous rats may appear to perform more poorly on tasks that involve more gross motor responses as a result of their increased locomotor activity. In contrast, performance in cognitive tasks without great motor demand is improved by physiological regimen of estrogen [81,96]. Thus, E2’s profound effects on activity and emotional arousal [55,56,68] may contribute to some of the different effects of E2 reported in cognitive tasks that diverge in the activity and/or arousal required for optimal performance. Because of these possible non-mnemonic factors, the present studies utilized a physiological concentration of E2 (10 µg, SC) that was administered after training in two tasks that have low (inhibitory avoidance) or high (water maze) motor demand.

Beneficial effects of E2 may be clearer in aging rodents. First, despite considerable differences between strains in age-related deficits in water maze performance [89,90], decline in spatial memory typically occurs with ageing. In general, this decline occurs earlier in female (~17 months), as compared to male (~24 months), mice and among females decline seems to coincide with cessation of ovarian function [24,51,60,61]. Second, E2 to senescent female or male rats improves spatial performance [32,48] and E2 to aged female mice enhances spatial and non-spatial performance [23,25,53,91]. However, whether the aforementioned effects of E2 were attributable to mnemonic- or performance-enhancing effects of E2 was not dissociated because E2 was present during training and testing. Given the ageing population, ascertaining the efficacy of treatments and the responsive populations, in which E2 may minimize age-related cognitive decline is becoming increasingly important [52,54,57]. As such, effects of post-training E2 administration to aged female or male mice (that have a varied genetic background) on spatial and non-spatial memory was investigated.

Another factor that may contribute to some of the variable effects previously reported for E2 on learning are its diverse mechanisms of action. E2’s ligand-dependent actions, via traditional intracellular E2 receptors (ERs) that have been localized to the hippocampus and forebrain [39], typically take hours to days to occur [67]. However, E2 can also have rapid effects via actions at neuronal membranes [88]. Some of E2’s mnemonic effects may be due in part to its modulation of neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF affects neuronal survival, differentiation, and synaptic plasticity, and the gene for BDNF has an estrogen response element [47,87]. BDNF has been implicated in learning and memory and Alzheimer’s Disease [58,97]. Notably, BDNF is abundant in the hippocampus and is altered by E2 exposure [3,8,46]. For these reasons, E2’s effects on BDNF levels in the hippocampus were examined.

The present studies utilized female and male mice to examine effects of E2 on learning. We hypothesized that if E2 can produce mnemonic effects via either rapid or sustained actions in aged mice, then post-training administration of E2 would be expected to improve learning in the inhibitory avoidance and water maze tasks.

2. Materials and methods

Procedures were pre-approved by The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at SUNY-Albany.

2.1. Subjects and housing

Subjects were 24-month-old congenic mice (having primarily a C57BL/6J background; n = 16 females, n = 14 males), raised and group-housed in the Laboratory Animal Care Facility at The University at Albany [12,93].

2.2. Hormonal milieu

Mice were left intact, as male mice would be expected to have low endogenous E2 concentrations and aged female mice would be expected to have E2 levels that have reached nadir [60,66]. Further, surgical procedures in mice of this age are contraindicated due to attrition that would be produced.

Regimen of E2 ranging from 0.5 to 10 µg have been utilized previously to produce physiological concentrations of E2 [16]. There are strain differences in responsiveness to gonadal hormones, which may be more apparent in congenic mice [85]. Further, older animals may be less responsive to E2 administration. For these reasons, we employed the highest known regimen that has been utilized to produce physiological E2 levels in mice (10 µg). Immediately following training in the behavioral tasks, mice were administered SC E2 or vehicle (sesame oil). Our lab, and others’, have previously demonstrated that exposure to E2 within 1 h of training is critical for consolidation [50,65,70].

2.3. Procedure

Mice were randomly assigned to receive E2 or vehicle injections. All mice were first trained and tested in the inhibitory avoidance task and then in the water maze task, as described below. After testing, some mice were re-administered E2 or vehicle for tissue collection for measurement of hippocampal E2 and BDNF levels. Mice were kept in the same condition for both tests and tissue collection. There was a 7- to 10-day washout period between each E2 injection. Although this is a sufficient washout period for younger animals, whether aged animals can clear E2 as efficiently is not known. Thus, there may have been carryover effects of E2 administration.

2.4. Behavioral testing

2.4.1. Inhibitory avoidance

During week 1, mice were trained and tested in the inhibitory avoidance task, using modified methods described in previous reports [28,30,69]. Briefly, mice were placed in the two-chambered inhibitory avoidance apparatus that is equally partitioned by a sliding door (one side white and brightly-lit; one side black and not illuminated). 20 min later, mice were placed on the light side of the chamber and the door was lifted. When the mouse crossed to the dark side, the door was closed and a shock was administered (0.25 mA, 5-s duration). Immediately after training, mice were administered 10 µg SC E2 or oil vehicle. 24 h after training, mice were placed on the light side of the chamber, the door was lifted, and the latency to cross-over was recorded (maximum latency, 300 s).

2.4.2. Water maze

During week 2, mice were trained and tested in a water maze task using methods previously described [24,25,94]. On day 1, mice were placed on the hidden platform (8 cm in diameter) in the water maze (97 cm in diameter) and then allowed to swim freely in the maze for 1 min. On day 2, mice were given twelve trials, organized into three blocks of 4 trials (one trial/start position within a block). The four trials within a block were separated by 10 s. Each block of trials was separated by 30 min. Immediately following the last trial (trial 12), mice were administered 10 µg SC E2 or vehicle. 30 min later, mice were given a 1-min probe trial in which the platform was not available for escape. The start point for the probe trial was randomly selected for each subject. The latency to cross where the platform had been, and the duration of time spent in the quadrant where the platform was during training, were recorded. To address possible non-mnemonic effects of E2 on performance, 20 min following the probe trial, a cued task was conducted. A visible platform was raised above the surface of the water and placed in a different quadrant for each of the four trials. The latency to reach the platform in each trial was recorded.

2.5. Biochemical measures

2.5.1. Tissue collection

One week following water maze testing, some mice (n = 6/group) were put into the same hormonal conditions as they were in for behavioral testing. One or 24 h after E2 or vehicle administration mice were killed by cervical dislocation and brains were rapidly removed and placed on dry ice followed by storage at −70 °C until measurement.

2.5.2. Tissue preparation

Immediately prior to measurement of E2 and BDNF levels, unilateral hippocampus were dissected on ice and weighed. Tissues were homogenized in a glass/glass homogenizer in 2 ml of distilled water. These homogenates were then utilized to measure E2 (radioimmunoassay) and BDNF (ELISA) levels in the hippocampus.

2.5.3. Radioimmunoassay for E2 levels in hippocampus

For measurement of hippocampal levels of E2, 600 µl of the above preparation was extracted twice with ether by snap freezing. Following chromatographic separation, TMP was evaporated, and pellets were reconstituted in PBS (pH = 7.4). The standard curve was prepared in duplicate (12.5–1000 pg/0.1 ml). Standards were added to PBS, with E2 antibody (Dr. Niswender, #244, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO), and [3H] E2 (NET-317, 51.3 ci/mmol; New England Nuclear, Boston, MA, 8000 dpm/100 ml). Assay tubes were incubated at room temperature for 50 min. Separation of bound and free occurred with dextran-coated charcoal and centrifugation at 3000 × g for 10 min following a 10-min incubation on ice. Supernatant was counted using a Tri-Carb 2000CA Liquid Scintillation Analyzer. Unknowns were interpolated from the standard curve using Assay Zap, a program for RIA analyses.

2.5.4. ELISA for BDNF levels in hippocampus

BDNF levels in the hippocampus were examined utilizing the Promega BDNF Emax Immunoassay System (Promega, Madison, WI). Briefly, 200 µl Promega lysis buffer was added to 100 µl aliquots of previously prepared samples. Samples were sonicated with a microtip at power level 4 for 15 s. Samples were then centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 30 min. Twenty-five µl aliquots of the resulting supernatant were removed and diluted with 100 µl of DPBS buffer. 100 µl anti-BDNF monoclonal antibody (mAB) diluted 1:1000 in carbonate coating buffer was applied to a 96-well polystyrene plate and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Unabsorbed mAB was removed and plates were washed once with TBST wash buffer. Plates were blocked using 200 µl Promega 1× Block and Sample buffer followed by incubation, without shaking, for 1 h at room temperature. Plates were then washed once using TBST wash buffer. Two hundred µl of each standard (0, 7.8, 15.6, 31.3, 62.5, 125, 250, 500 pg/ml) were added in duplicate to plates. One hundred µl of samples were added in duplicate to plates. Plates were incubated for 2 h with shaking at room temperature. Plates were then washed five times with TBST wash buffer. Anti-human BDNF polyclonal antibody (pAB; 100 µl diluted 1:500 in 1× Block and Sample buffer) was added to each well and plates were incubated for 2 h with shaking at room temperature. Plates were washed five times with TBST wash buffer. Anti-Ig Y horseradish peroxidase conjugate (100 µl diluted 1:200 in 1× Block and Sample buffer) was then added to each well and plates were incubated for 1 h with shaking at room temperature. Plates were emptied again and washed five times with TBST wash buffer. Finally, plates were developed using 100 µl Promega TMB One Solution and the reaction was stopped at 10 min using 100 µl 1 N HCl. Protein was measured using Bradford’s method [7]. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm. BDNF levels are reported as ng/mg tissue.

2.6. Statistical analyses

Effects of E2 administration on inhibitory avoidance and water maze learning were compared across groups using two-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) using hormone (E2 or vehicle) and sex (female or male) as factors. As there were no effects of sex on behavior and tissues collected from a subset of animals (which would yield a small number of observations using sex as a variable), sex was not considered a factor when analyzing biochemical measures. One-way ANOVAs were used to examine effects of vehicle, and 1 or 24 h of E2 exposure on E2 and BDNF levels in the hippocampus. Alpha level for statistical significance was P < 0.05. Where appropriate, Fisher’s post hoc tests were used to determine group differences.

3. Results

3.1. Inhibitory avoidance

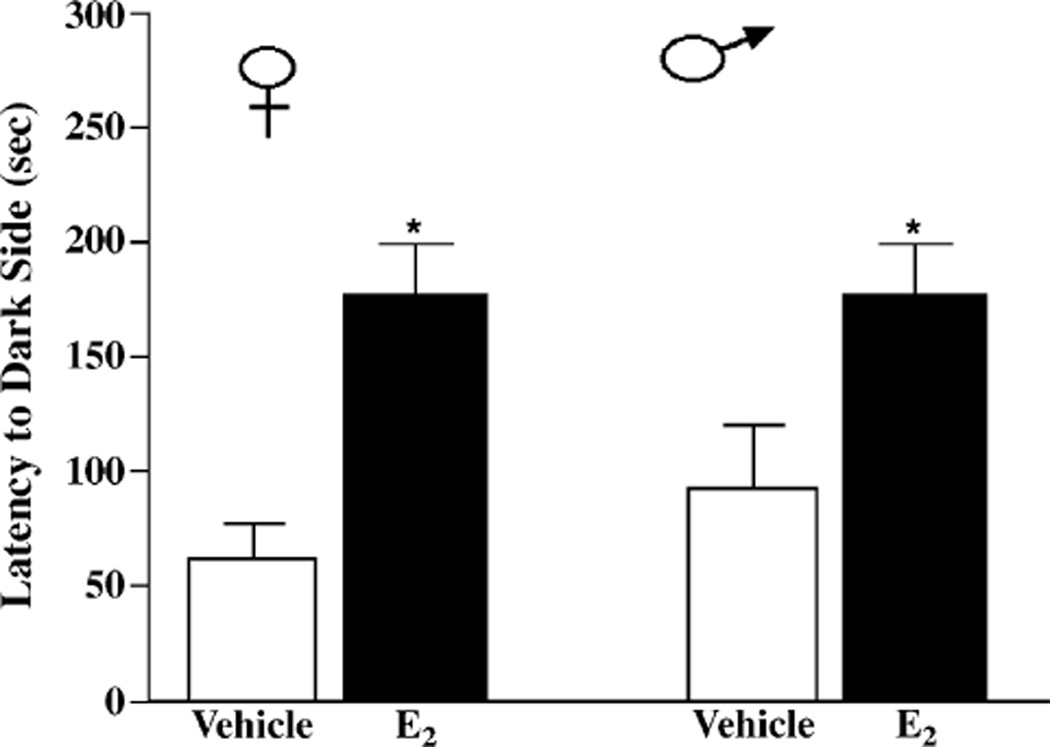

E2 enhanced inhibitory avoidance learning of female and male mice. There was a main effect of hormone on cross-over latencies on test day (F(1,26) = 12.44, P < 0.05). Female and male mice administered E2 had significantly longer latencies to cross-over to the dark, shock-associated side of the chamber compared to their counterparts administered vehicle (Fig. 1). There was no main effect of sex on cross-over latencies on test day (F(1,26) = 0.58, P > 0.05). The better performance of E2-administered mice was not due to differences in latencies on training day. There were no main effects of sex (F(1,26) = 0.5, P > 0.05) or hormone (F(1,26) = 0.04, P > 0.05) on cross-over latencies on training day.

Fig. 1.

Latencies to cross-over to the dark, shock-associated side of the training apparatus of female (left) or male (right) mice administered post-training vehicle (n = 8 female, n = 7 male, white bars) or 10 µg E2 (n = 8 females, n = 7 males, black bars). * indicates significantly different from vehicle (P < 0.05).

3.2. Water maze

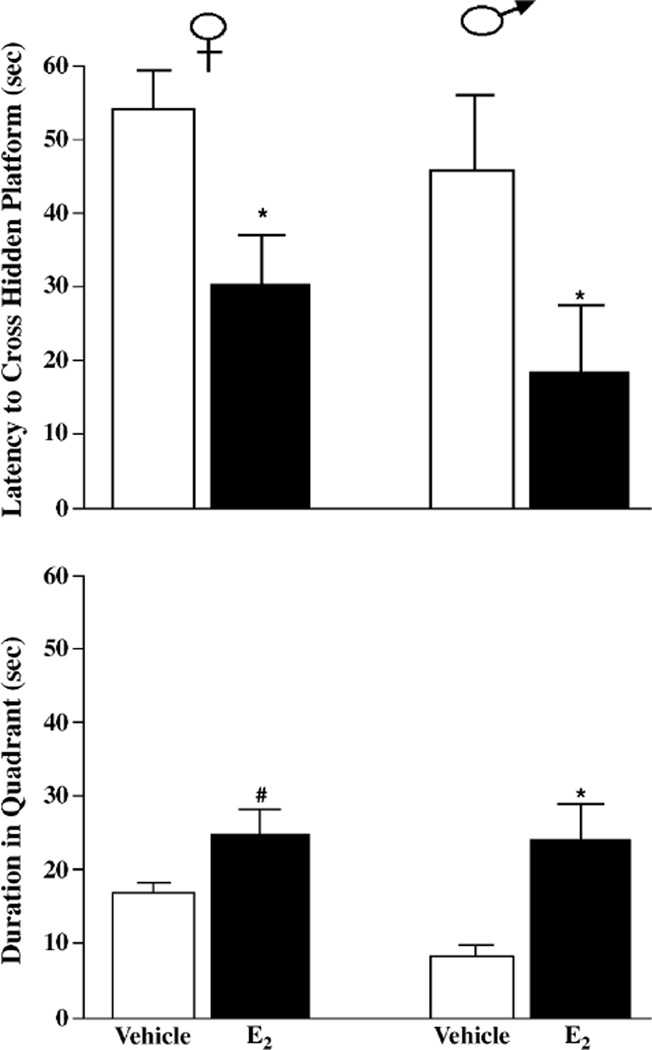

Learning of female and male mice in the water maze was improved by E2. There was a main effect of hormone, but not sex, on the latency to cross the hidden platform (F(1,26) = 13.91, P < 0.05 and F(1,26) = 3.25, P > 0.05, respectively) and duration of time spent in the quadrant where the platform had been during training (F(1,26) = 13.27, P < 0.05 and F(1,26) = 0.44, P > 0.05, respectively). Female or male mice administered E2 had significantly shorter latencies to cross the hidden platform and spent significantly more time in the quadrant where the platform had been compared to their vehicle-administered counterparts (Fig. 2). Training latencies to find the hidden platform were not different among the groups. There was no main effect of hormone (F(1,26) = 0.05, P > 0.05) or sex (F(1,26) = 1.21, P > 0.05) on latencies to find the platform across training trials.

Fig. 2.

Latencies to cross (top), and duration spent swimming in (bottom), the quadrant where the platform had been during training of female (left) or male (right) mice administered post-training vehicle (n = 8 females, n = 7 males, white bars) or 10 µg E2 (n = 8 females, n = 7 males, black bars). * indicates significantly different from vehicle (P < 0.05). #indicates tendency for difference from vehicle (P, 0.10).

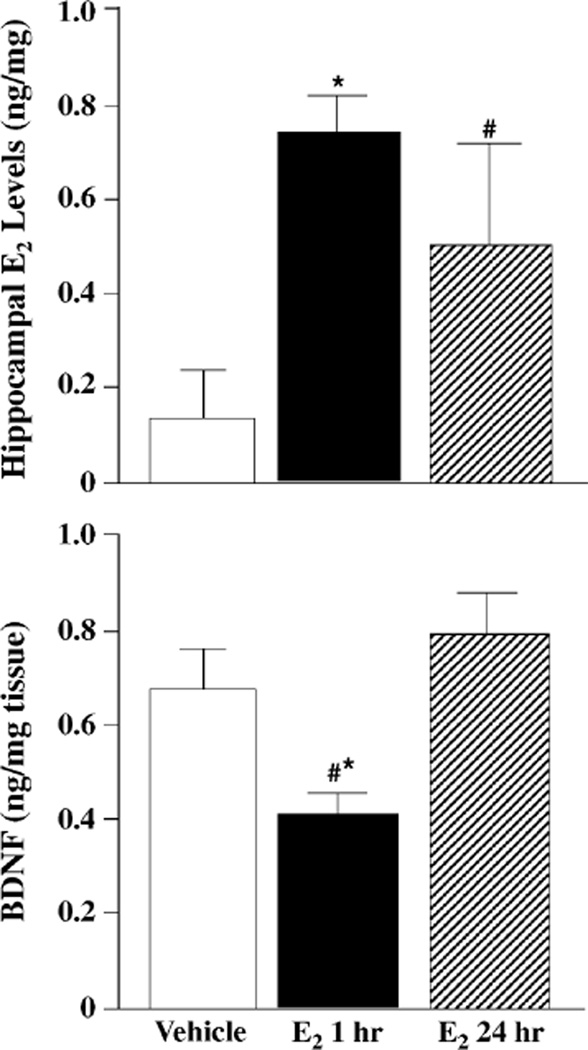

3.3. Hippocampal E2 levels

E2 administration increased hippocampal E2 levels (F(2,15) = 4.29, P < 0.05). E2 levels in the hippocampus were significantly higher 1 h following E2 administration and tended to be higher 24 h after E2 administration compared to vehicle (Fig. 3, top).

Fig. 3.

Hippocampal levels of E2 (top) or BDNF (bottom) of mice exposed to vehicle (n = 6, white bars), 1 h (n = 6, black bars), or 24 h (n = 6, striped bars) of E2. Top panel * indicates significantly different from vehicle (P < 0.05) and # indicates tendency for difference from vehicle (P < 0.10). Bottom panel * indicates significantly different from E2 24 h and # indicates tendency for difference from vehicle.

3.4. Hippocampal BDNF levels

BDNF levels in the hippocampus were altered by E2 administration (F(2,15) = 3.75, P < 0.05). One hour following E2 administration, BDNF levels in the hippocampus were decreased compared to vehicle. There were no differences in BDNF levels in the hippocampus 24 h after E2 administration compared to vehicle (Fig. 3, bottom).

4. Discussion

These results support the hypothesis that E2 has enhancing effects on memory of aged female and male mice. Previous studies have demonstrated age-related decline in learning of male and female mice and that E2 to female mice can overcome age-related deficits in cognitive performance [22,24,25]. The present results extend these prior studies in several important ways. First, E2 had similar beneficial effects when administered to aged female or male mice (with a variable genetic background) as has been previously reported for aged female C57BL/6 mice [24,25]. Second, in previous studies, beneficial effects of E2 were observed when E2 was present during training and testing. The present effects of post-training E2 demonstrate that E2 can have mnemonic effects in aged mice. Third, exogenous E2 produced particularly rapid effects (within 30 min) in the water maze, but also effects that were sustained and salient neurorestorative effects in the inhibitory avoidance task 24 h later in these aged mice. Given that the E2 regimen employed in the present studies produced modest E2 levels in the hippocampus 1 and 24 h after E2 administration, these results suggest that physiologically-relevant concentrations of E2 may have important cognitive-enhancing effects.

Mnemonic effects of E2 were evident in both the inhibitory avoidance and water maze tasks, which suggests that some of E2’s beneficial effects may involve the hippocampus. First, the hippocampus mediates spatial and explicit memory function and is integral to performance in the inhibitory avoidance and water maze tasks [17,36]. Second, E2 produces changes in hippocampal physiology and morphology that has recently been related to cognitive performance [86]. E2 to ovariectomized C57BL/6J mice enhances performance in the object placement task, a spatial episodic memory task, and increases the number of dendritic spines with mushroom shapes in the dorsal hippocampus [44]. Although E2 can have actions in the hippocampus for its mnemonic effects, this does not preclude the involvement of actions of E2 in other brain areas for enhanced learning.

The mechanisms for E2’s mnemonic effects have not been identified. E2 may have actions in the hippocampus to improve learning via traditional ligand-dependent actions at intracellular ERs [19,20,42]. In support, E2 administered to ERβ knockout mice does not enhance spatial learning compared to vehicle [73]. Further, there may be ER specific effects of E2 to enhance learning. Ligands with specific activity at ERa or ERβ can enhance learning [43,50,71]. However, these data do not preclude non-ER mediated effects of E2 to enhance learning. For example, ER antagonists fail to block E2’s effects on inhibitory avoidance. Systemic administration of tamoxifen or intra-hippocampal ICI 182,780 does not attenuate the mnemonic effects of intra-hippocampal E2 in the inhibitory avoidance task of rats [28,30]. Further, other models have demonstrated that membrane actions of E2 may propagate later actions at ERs [92]. The present results that post-training exposure to E2 for 30 min is sufficient to enhance learning in the water maze, and post-training E2 for 24 h improves learning in the inhibitory avoidance task is consistent with times frames required for membrane (latencies within seconds) and ER-mediated actions (latencies within 15 min) [67]. Although timeframe does not directly address E2’s mechanism, to our knowledge, these results demonstrate the most rapid mnemonic effects of E2 that have been reported. Further, more rapid effects are unlikely to be demonstrated, as a 1-h post-training consolidation period is necessary for E2’s mnemonic effects.

To more directly address E2’s mechanism, BDNF levels in the hippocampus were examined. One hour following E2 administration, BDNF levels in the hippocampus were decreased compared to vehicle. It is possible that E2 may have enhanced learning by down-regulating BDNF. E2 down-regulates BDNF in cultured hippocampal neurons, which decreases inhibition and increases excitatory tone in pyramidal neurons, leading to a 2-fold increase in dendritic spine density [59]. Thus, in the present studies, reduced BDNF following 1 h of E2 exposure may reduce GABAergic neurotransmission, leading to increased spine growth and enhanced memory. Notably, BDNF following 24 h of E2 exposure was not different than that seen following vehicle. However, previous data have demonstrated that the critical timeframe for consolidation of learning is within 1 h of training [50, 65,70]. Given the relevance of E2’s neurorestorative actions for aging populations, the mechanisms associated with E2’s rapid and sustained effects need to be investigated further.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the grant support provided by The National Science Foundation (DBI 00-97343, IBN03-16083), The National Institute of Mental Health (MH067698), and SUNY-Albany.

References

- 1.Asthana S, Baker LD, Craft S, Stanczyk FZ, Veith RC, Raskind MA, Plymate SR. High-dose estradiol improves cognition for women with AD: results of a randomized study. Neurology. 2001;57:605–612. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beatty WW. Gonadal hormones and sex differences in nonreproductive behaviors. In: Gerall AA, Moltz H, War IL, editors. Handbook of Behavioral Neurobiology, Sexual Differentiation. vol. 11. New York: Plenum Press; 1992. pp. 85–128. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berchtold NC, Kesslak JP, Pike CJ, Adlard PA, Cotman CW. Estrogen and exercise interact to regulate brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA and protein expression in the hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2001;14:1992–2002. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berry B, McMahan R, Gallagher M. Spatial learning and memory at defined points of the estrous cycle: effects on performance of a hippocampal-dependent task. Behav. Neurosci. 1997;111:267–274. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bimonte HA, Denenberg VH. Estradiol facilitates performance as working memory load increases. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1999;24:161–173. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(98)00068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binder EF, Schectman KB, Birge SJ, Williams DB, Kohort WM. Effects of hormone replacement therapy on cognitive performance in elderly women. Maturitas. 2001;38:137–146. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(00)00214-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–252. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cavus I, Duman RS. Influence of estradiol, stress, and 5-HT2A agonist treatment on brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in female rats. Biol. Psychiatry. 2003;54:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00236-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cherrier MM, Asthana S, Plymate S, Baker L, Mastsumoto AM, Peskind E, Raskind MA, Brodkin K, Bremmer W, Petrova A, LaTendresse S, Craft S. Testosterone supplementation improves spatial and verbal memory in healthy older men. Neurology. 2001;57:80–88. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chesler EJ, Juraska JM. Acute administration of estrogen and progesterone impairs the acquisition of the spatial Morris water maze in ovariectomized rats. Horm. Behav. 2000;38:234–242. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2000.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Christiansen K. Sex hormone-related variations of cognitive performance in !Kung San hunter-gatherers of Namibia. Neuropsychobiology. 1993;7:97–107. doi: 10.1159/000118961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crabbe JC, Wahlsten D, Dudek BC. Genetics of mouse behavior: interactions with laboratory environment. Science. 1999;284:1670–1672. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5420.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daniel JM, Fader AJ, Spencer AL, Dohanich GP. Estrogen enhances performance of female rats during acquisition of a radial arm maze. Horm. Behav. 1997;32:217–225. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1997.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz-Veliz G, Soto V, Dussaubat N, Mora S. Influence of the estrous cycle, ovariectomy and estradiol replacement upon the acquisition of conditioned avoidance responses in rats. Physiol. Behav. 1989;46:397–401. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(89)90010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durante R, Lachman M, Mohr B, Longcope C, McKinlay JB. Is there a relation between hormones and cognition in older me? Al. J. Epidemiol. 1997;145:S2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards DA. Induction of estrus in female mice: estrogen-progesterone interactions. Horm. Beahav. 1970;1:299–304. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eichenbaum H, Otto T, Cohen NJ. The hippocampus—what does it do? Behav. Neural Biol. 1992;57:2–36. doi: 10.1016/0163-1047(92)90724-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Errico AL, Parsons OA, Kling OR, King AC. Investigation of the role of sex hormones in alcoholics’ visuospatial deficits. Neuropsychologia. 1992;30:417–426. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(92)90089-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etgen AM. Progestin receptors and the activation of female reproductive behavior: a critical review. Horm. Behav. 1984;18:411–430. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(84)90027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Falkenstein E, Tillmann HC, Christ M, Feuring M, Wehling M. Multiple actions of steroid hormones—a focus on rapid, nongenomic effects. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000;52:513–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farr SA, Flood JF, Scherrer JF, Kaiser FE, Taylor GT, Morley JE. Effect of ovarian steroids on footshock avoidance learning and retention in female mice. Physiol. Behav. 1995;58:715–723. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)00124-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fordyce DE, Wehner JM. Physical activity enhances spatial learning performance with an associated alteration in hippocampal protein kinase C activity in C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice. Brain Res. 1993;619:111–119. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91602-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forster MJ, Dubey A, Dawson KM, Stutts WA, Lal H, Sohal RS. Age-related losses of cognitive function and motor skills in mice are associated with oxidative protein damage in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1996;93:4765–4769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frick KM, Burlingame LA, Arters JA, Berger-Sweeney J. Reference memory, anxiety and estrous cyclicity in C57BL/6NIA mice are affected by age and sex. Neuroscience. 2000;95:293–307. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00418-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frick KM, Fernandez SM, Bulinski SC. Estrogen replacement improves spatial reference memory and increases hippocampal synaptophysin in aged female mice. Neuroscience. 2002;115:547–558. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frye CA. Estrus-associated decrements in a water maze task are limited to acquisition. Physiol. Behav. 1995;57:5–14. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00197-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frye CA. Estradiol tends to improve inhibitory avoidance performance in adrenalectomized male rats and reduces pyknotic cells in the dentate gyrus of adrenalectomized male and female rats. Brain Res. 2001;889:358–363. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03236-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frye CA, Rhodes ME. Enhancing effects of estrogen on inhibitory avoidance performance may be in part independent of intracellular estrogen receptors in the hippocampus. Brain Res. 2002;956:285–293. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03559-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frye CA, Petralia SM, Rhodes ME. Estrous cycle and sex differences in performance on anxiety tasks coincide with increases in hippocampal progesterone and 3α,5α-THP. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2000;67:587–596. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00392-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fugger HN, Foster TC, Gustafsson J, Rissman EF. Novel effects of estradiol and estrogen receptor α and β on cognitive function. Brain Res. 2000;883:258–264. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02993-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Galea LA, Kavaliers M, Ossenkopp KP, Hampson E. Gonadal hormone levels and spatial learning performance in the Morris water maze in male and female meadow voles, Microtus pennsylvanicus. Horm. Behav. 1995;2:106–125. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1995.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibbs RB. Effects of gonadal hormone replacement on measures of basal forebrain cholinergic function. Neuroscience. 2000;101:931–938. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00433-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gibbs RB, Burke AM, Johnson DA. Estrogen replacement attenuates effects of scopolamine and lorazepam on memory acquisition and retention. Horm. Behav. 1998;34:112–125. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hogervorst E, Williams J, Budge M, Riedel W, Jolles J. The nature of the effect of female gonadal hormone replacement therapy on cognitive function in post-menopausal women: a meta-analysis. Neuroscience. 2000;101:485–512. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00410-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holmes MM, Wide JK, Galea LA. Low levels of estradiol facilitate, whereas high levels of estradiol impair, working memory performance on the radial arm maze. Behav. Neurosci. 2002;116:928–934. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.116.5.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Izquierdo I, Medina JH. Memory formation: the sequence of biochemical events in the hippocampus and its connection to activity in other brain structures. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 1997;68:285–316. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1997.3799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janowsky JS, Chavez B, Orwoll E. Sex steroids modify working memory. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2000;12:407–414. doi: 10.1162/089892900562228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kampen DL, Sherwin DB. Estradiol is related to visual memory in healthy young men. Behav. Neurosci. 1996;110:613–617. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.110.3.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koch M, Ehret G. Immunocytochemical localization and quantitation of estrogen-binding cells in the male and female (virgin, pregnant, lactating) mouse brain. Brain Res. 1989;489:101–112. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(89)90012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Komnenich P, Lane DM, Dickey RP, Stone SC. Gonadal hormones and cognitive performance. Physiol. Psychol. 1978;6:115–120. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Korol DL, Malin EL, Borden KA, Busby RA, Couper-Leo J. Shifts in preferred learning strategy across the estrous cycle in female rats. Horm. Behav. 2004;45:330–338. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krezel W, Dupont S, Krust A, Chambon P, Chapman PF. Increased anxiety and synaptic plasticity in estrogen receptor β-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:12278–12282. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221451898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lephart ED, West TW, Weber KS, Rhees RW, Setchell KD, Adlercreutz H, Lund TD. Neurobehavioral effects of dietary soy phytoestrogens. Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 2002;24:5–16. doi: 10.1016/s0892-0362(01)00197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li C, Brake WG, Romeo RD, Dunlop JC, Gordon M, Buzescu R, Magarinos AM, Allen PB, Greengard P, Luine V, McEwen BS. Estrogen alters hippocampal dendritic spine shape and enhances synaptic protein immunoreactivity and spatial memory in female mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:2185–2190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307313101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Linzmayer L, Semlitsch HV, Saletu B, Bock G, Saletu-Zyhlarz G, Zoghlami A, Gruber D, Metka M, Huber J, Oettel M, Graser T, Grunberger J. Double-blind, placebo-controlled psychometric studies on the effects of a combined estrogen-progestin regimen versus estrogen alone on performance, mood and personality of menopausal syndrome patients. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 2001;51:238–245. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1300030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Fowler CD, Young LJ, Yan Q, Insel TR, Wang Z. Expression and estrogen regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene and protein in the forebrain of female prairie voles. J. Comp. Neurol. 2001;14:499–514. doi: 10.1002/cne.1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu B, Chow A. Neurotrophins and hippocampal synaptic transmission and plasticity. J. Neurosci. Res. 1999;1:76–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luine V, Rodriguez M. Effects of estradiol on radial arm maze performance of young and aged rats. Behav. Neural Biol. 1994;62:230–236. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(05)80021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luine VN, Richards ST, Wu VY, Beck KD. Estradiol enhances learning and memory in a spatial memory task and effects levels of monoaminergic neurotransmitters. Horm. Behav. 1998;34:149–162. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Luine VN, Jacome LF, Maclusky NJ. Rapid enhancement of visual and place memory by estrogens in rats. Endocrinology. 2003;144:2836–2844. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Markowska AL. Sex dimorphisms in the rate of age-related decline in spatial memory: relevance to alterations in the estrous cycle. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:8122–8133. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-08122.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Markowska AL, Stone WS, Ingram DK, Reynolds J, Gold PE, Conti LH, Pontecorvo MJ, Wenk GL, Olton DS. Individual differences in aging: behavioral and neurobiological correlates. Neurobiol. Aging. 1989;10:31–43. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(89)80008-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller MM, Hyder SM, Assayag R, Panarella SR, Tousignant P, Franklin KB. Estrogen modulates spontaneous alternation and the cholinergic phenotype in the basal forebrain. Neuroscience. 1999;91:1143–1153. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00690-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miranda P, Williams CL, Einstein G. Granule cells in aging rats are sexually dimorphic in their response to estradiol. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:3316–3325. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03316.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morgan MA, Pfaff DW. Effects of estrogen on activity and fear-related behaviors in mice. Horm. Behav. 2001;40:472–482. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morgan MA, Schulkin J, Pfaff DW. Estrogens and non-reproductive behaviors related to activity and fear. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2004;28:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mortality and morbidity weekly report. Trends in Aging—United States and Worldwide. 2003;52:101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Murer MG, Yan Q, Raisman-Vozari R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the control human brain, and in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2001;69:71–124. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Murphy DD, Cole NB, Segal M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor mediates estradiol-induced dendritic spine formation in hippocampal neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998;95:11412–11417. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nelson JF, Felicio LS, Osterburg HH, Finch CE. Differential contributions of ovarian and extraovarian factors to age-related reductions in plasma estradiol and progesterone during the estrous cycle of C57BL/6J mice. Endocrinology. 1992;130:805–810. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.2.1733727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nelson JF, Karelus K, Bergman MD, Felicio LS. Neuroendocrine involvement in aging: evidence from studies of reproductive aging and caloric restriction. Neurobiol. Aging. 1995;16:837–843. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(95)00072-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nikolov R, Kuhl H, Golbs S. Estrogen replacement therapy and Alzheimer’s disease. Drugs Today (Barc) 1998;34:927–933. doi: 10.1358/dot.1998.34.11.487476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.O’Neal MF, Means LW, Poole MC, Hamm RJ. Estrogen affects performance of ovariectomized rats in a two-choice water-escape working memory task. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:51–65. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Packard MG. Posttraining estrogen and memory modulation. Horm. Behav. 1998;34:126–139. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Packard MG, Teather LA. Posttraining estradiol injections enhance memory in ovariectomized rats: cholinergic blockade and synergism. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 1997;68:172–188. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1997.3785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Perrot-Sinal TS, Kavaliers M, Ossenkopp KP. Spatial learning and hippocampal volume in male deer mice: relations to age, testosterone and adrenal gland weight. Neuroscience. 1998;86:1089–1099. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00131-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pfaff DW, McEwen BS. Actions of estrogens and progestins on nerve cells. Science. 1983;219:808–814. doi: 10.1126/science.6297008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pfaff DW, Frohlich J, Morgan M. Hormonal and genetic influences on arousal—sexual and otherwise. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:45–50. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quertemont E, Tambour S, Bernaerts P, Zimatkin SM, Tirelli E. Behavioral characterization of acetaldehyde in C57BL/6J mice: locomotor, hypnotic, anxiolytic and amnesic effects. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 2004;177:84–92. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1911-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rhodes ME, Frye CA. Estrogen has mnemonic-enhancing effects in the inhibitory avoidance task. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2004;78:551–558. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rhodes ME, Frye CA. ERβ-selective SERMs produce mnemonic-enhancing effects in the inhibitory avoidance and water maze tasks. Learn. Mem. 2004 doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2005.10.003. (submitted for publication). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rissanen A, Puolivali J, van Groen T, Riekkinen P., Jr In mice tonic estrogen replacement therapy improves non-spatial and spatial memory in a water maze task. NeuroReport. 1999;10:1369–1372. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199904260-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rissman EF, Heck AL, Leonard JE, Shupnik MA, Gustafsson JA. Disruption of estrogen receptor beta gene impairs spatial learning in female mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:3996–4001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012032699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sandstrom NJ, Williams CL. Memory retention is modulated by acute estradiol and progesterone replacement. Behav. Neurosci. 2001;115:384–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Senanarong V, Vannasaeng S, Poungvarin N, Ploybutr S, Udompunthurak S, Jamjumras P, Fairbanks L, Cummings JL. Endogenous estradiol in elderly individuals: cognitive and noncognitive associations. Arch. Neurol. 2002;59:385–389. doi: 10.1001/archneur.59.3.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sherwin BB. Estrogen and/or androgen replacement therapy and cognitive functioning in surgically menopausal women. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1988;13:345–357. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(88)90060-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sherwin BB. Hormones, mood, and cognitive functioning in postmenopausal women. Obstet. Gynecol. 1996;87:20S–26S. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00431-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sherwin BB. Estrogen effects on cognition in menopausal women. Neurology. 1997;48:S21–S26. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.5_suppl_7.21s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sherwin BB. Can estrogen keep you smart? evidence from clinical studies. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 1999;24:315–321. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sherwin BB. Oestrogen and cognitive function throughout the female lifespan. Novartis Found. Symp. 2000;230:188–196. doi: 10.1002/0470870818.ch14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shors TJ, Lewczyk C, Pacynski M, Mathew PR, Pickett J. Stages of estrous mediate the stress-induced impairment of associative learning in the female rat. NeuroReport. 1998;9:419–423. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199802160-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Shumaker SA, Legault C, Rapp SR, Thal L, Wallace RB, Ockene JK, Hendrix SL, Jones BN, 3rd, Assaf AR, Jackson RD, Kotchen JM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Wactawski-Wende J. Estrogen plus progestin and the incidence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Memory Study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2651–2662. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Singh M, Meyer EM, Simpkins JW. The effect of ovariectomy and estradiol replacement on brain-derived neurotrophic factor messenger ribonucleic acid expression in cortical and hippocampal brain regions of female Sprague–Dawley rats. Endocrinology. 1995;136:2320–2324. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.5.7720680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Stackman RW, Blasberg ME, Langan CJ, Clark AS. Stability of spatial working memory across the estrous cycle of Long–Evans rats. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 1997;67:167–171. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1996.3753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Svare B. Genotype modulates the aggression-promoting quality of progesterone in pregnant mice. Horm. Behav. 1988;22:90–99. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(88)90033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tanapat P, Hastings NB, Reeves AJ, Gould E. Estrogen stimulates a transient increase in the number of new neurons in the dentate gyrus of the adult female rat. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:5792–5801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05792.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thoenen H. Neurotrophins and activity-dependent plasticity. Prog. Brain Res. 2000;128:183–191. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(00)28016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Toran-Allerand CD. Minireview: a plethora of estrogen receptors in the brain: where will it end? Endocrinology. 2004;145:1069–1074. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Upchurch M, Wehner JM. Differences between inbred strains of mice in Morris water maze performance. Behav. Genet. 1988;18:55–68. doi: 10.1007/BF01067075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Upchurch M, Wehner JM. DBA/2Ibg mice are incapable of cholinergically-based learning in the Morris water task. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1988;29:325–329. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90164-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Vaucher E, Reymond I, Najaffe R, Kar S, Quirion R, Miller MM, Franklin KB. Estrogen effects on object memory and cholinergic receptors in young and old female mice. Neurobiol. Aging. 2002;23:87–95. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00250-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vasudevan N, Kow LM, Pfaff DW. Early membrane estrogenic effects required for full expression of slower genomic actions in a nerve cell line. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:12267–12271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221449798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wahlsten D, Crabbe JC, Dudek BC. Behavioural testing of standard inbred and 5HT(1B) knockout mice: implications of absent corpus callosum. Behav. Brain Res. 2001;125:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wahlsten D, Metten P, Phillips TJ, Boehm SL, 2nd, Burkhart-Kasch S, Dorow J, Doerksen S, Downing C, Fogarty J, Rodd-Henricks K, Hen R, McKinnon CS, Merrill CM, Nolte C, Schalomon M, Schlumbohm JP, Sibert JR, Wenger CD, Dudek BC, Crabbe JC. Different data from different labs: lessons from studies of gene–environment interaction. J. Neurobiol. 2003;54:283–311. doi: 10.1002/neu.10173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Warren SG, Juraska JM. Spatial and nonspatial learning across the rat estrous cycle. Behav. Neurosci. 1997;111:259–266. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.111.2.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wood GE, Bevlin AV, Shors TJ. The contribution of adrenal and reproductive hormones to the opposing effects of stress on trace conditioning in males versus females. Behav. Neurosci. 2001;115:175–187. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.115.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yamada MK, Nakanishi K, Ohba S, Nakamura T, Ikegaya Y, Nichiyama N, Matsuki N. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes the maturation of GABAergic mechanisms in cultured hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:7580–7585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-17-07580.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]