Abstract

We introduce a fluorescent reporter for monitoring protein–protein interactions in living cells. The method is based on the Split-Ubiquitin method and uses the ratio of two auto-fluorescent reporter proteins as signal for interaction (SPLIFF). The mating of two haploid yeast cells initiates the analysis and the interactions are followed online by two-channel time-lapse microscopy of the diploid cells during their first cell cycle. Using this approach we could with high spatio-temporal resolution visualize the differences between the interactions of the microtubule binding protein Stu2p with two of its binding partners, monitor the transient association of a Ran-GTPase with its receptors at the nuclear pore, and distinguish between protein interactions at the polar cortical domain at different phases of polar growth. These examples further demonstrate that protein–protein interactions identified from large-scale screens can be effectively followed up by high-resolution single-cell analysis.

Keywords: fluorescent reporter, protein interaction, protein interaction networks, single-cell analysis, Split-Ubiquitin

Introduction

A mechanistic understanding of cellular biology requires a comprehensive knowledge about the protein interactions of the cell (Uetz et al, 2000; Gavin et al, 2002; Krogan et al, 2006; Yu et al, 2008; Breitkreutz et al, 2010). Split-protein sensors comprise a family of related techniques that contributed in small- and large-scale experiments to this cumulative endeavour (Miller et al, 2005; Tarassov et al, 2008; Hruby et al, 2011; Lowder et al, 2011; Stynen et al, 2012). The Split-Ubiquitin method (Split-Ub) is the prototype of these techniques (Müller and Johnsson, 2008; Stynen et al, 2012). Here, the N- and C-terminal halves of Ubiquitin (Nub and Cub) are coupled separately to the two proteins under study. Upon interaction of the fusion proteins, Nub and Cub are forced into close proximity and reassemble into a native-like Ubiquitin (Ub). The native-like Ub is recognized by Ub-specific proteases that cleave off a reporter protein that was genetically attached to the C-terminus of Cub (Johnsson and Varshavsky, 1994).

The cleavage of the Split-Ub reporter orothic acid decarboxylase (Ura3p, CRU) from Cub leads to a qualitative difference in bulk cell growth (Wittke et al, 1999). This and other proteome-wide interaction techniques produce binary protein–protein interaction maps. The information encoded in these maps could fundamentally transform our understanding of cellular processes. However, to be effectively used in cell biology these networks would need to acquire a spatial as well as temporal dimension in order to place the interactions into a functional and cellular context (Alexander et al, 2009). The reason for the prevalence of binary interaction maps is mainly technical. Currently, robust and easy-to-use approaches for the characterization of cellular protein interactions in space and time are not available.

Here, we report on a new method based on Split-Ub and two spectrally different fluorescent proteins (SPLIFF) to monitor the interaction between two proteins during the cell cycle with high spatial and temporal resolution. We further show that SPLIFF can bridge large-scale protein interaction screens with high-resolution single-cell analysis.

Results

Rational and design of measurements

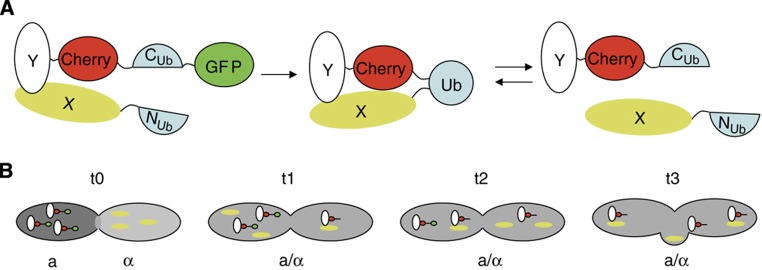

To create a robust and sensitive fluorescent reporter for protein interactions, we designed a Split-Ub module where Cub is sandwiched by two spectrally different fluorescent proteins (Cherry-Cub-GFP, CCG) (Figure 1A). Coupling CCG to the C-terminus of protein Y (Y-CCG) reveals the cellular localization of the fusion protein. Interaction of Y-CCG with a Nub-coupled interaction partner X will result in the cleavage of GFP from Y-CCG to create Y-CC. The liberated GFP is subsequently degraded. As Cherry stays attached to Y, the ratio of red to green fluorescence serves as a ratiometric reporter of protein–protein interactions and constitutes the actual readout of SPLIFF. To improve the spatial and temporal resolution of the assay, we defined the start of each reaction by fusing two yeast cells of opposite mating type, each expressing one half of the Split-Ub sensor (Figure 1B). The conversion of a Cherry/GFP-labelled (Y-CCG) into a Cherry-labelled fusion protein (Y-CC) is then recorded online by two-channel time-lapse fluorescence microscopy. This strategy is borrowed from chemical stopped-flow experiments where the kinetics of chemical reactions is recorded after forcing the reagents into a single chamber.

Figure 1.

Experimental design of SPLIFF. (A) Protein Y coupled to the Cherry-Cub-GFP (Y-CCG) interacts with the Nub fusion of protein X (Nub-X). Upon reassociation of Nub and Cub, the GFP is cleaved off and Y-CCG is converted to Y-CC. The N-terminally exposed arginine leads to rapid degradation of GFP. (B) Two yeast cells of the a- and α-mating type expressing Y-CCG (connected red and green circles) and Nub-X (yellow ellipsoid), respectively, fuse at t0. The cytosols mix, Y-CCG and Nub-X interact, leading to the progressive conversion of Y-CCG to Y-CC at t1, t2, and t3.

In the following experiments, we demonstrate the applicability of SPLIFF by investigating protein interactions that occur at different cellular locations over widely different time periods and by providing examples of successful transitions from large-scale to single-cell analysis.

Interactions in the nucleus

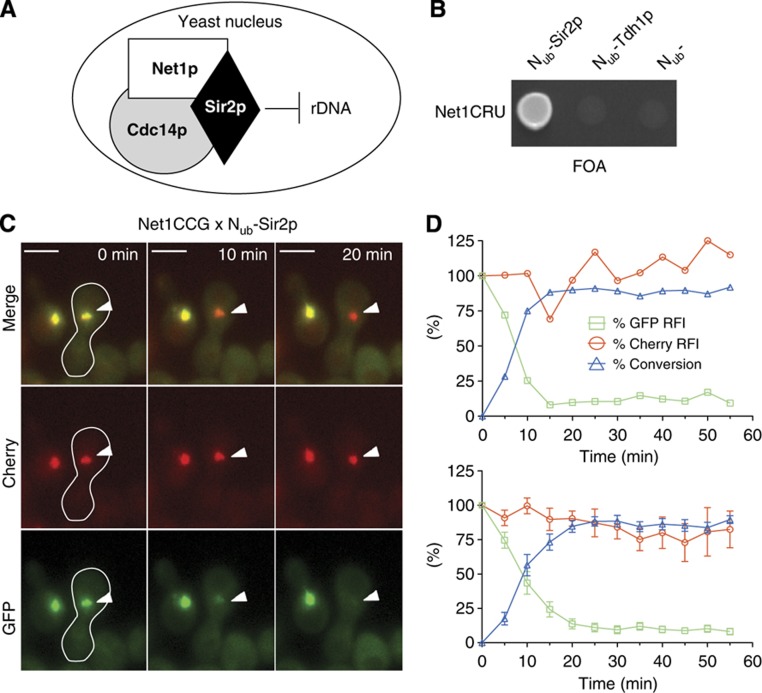

The interaction between the nucleolar protein Net1p and the NAD-dependent histone deacetylase Sir2p exemplifies the experimental approach (Straight et al, 1999; Figure 2). The CRU or CCG modules were attached in frame behind the ORF of NET1 by homologous recombination. The Nub module was fused 5′ to the SIR2 ORF in α cells. The expression of the Nub fusion was controlled by the PCUP1 promoter and could be adjusted by varying the levels of copper in the medium. The growth on 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) of cells co-expressing Net1CRU and Nub-Sir2p revealed the interaction in the chosen configuration of Nub and Cub attachment (Figure 2B). Subsequent time-lapse microscopy of the diploid cells originating from the mating of Net1CCG- and Nub-Sir2p expressing a- and α-cell visualized the course of interaction in the nucleus from the a-cells. The reaction was completed within 20 min even before nuclear fusion has occurred (Figure 2C and D; Supplementary Movie 1).

Figure 2.

SPLIFF analysis of the Net1p/Sir2p interaction. (A) Cartoon of the RENT complex. (B) Interaction between Net1p and Sir2p as measured by the Split-Ub growth assay. Cells expressing an interacting Nub fusion grow on medium containing 5-FOA. (C) Interaction between Net1p and Sir2p as measured by SPLIFF. Selected frames of the time-lapse analysis of the mating of two yeast cells expressing Net1CCG and Nub-Sir2, respectively, (white border) are shown. Nuclei of unfarmed cells belong to haploid a-cells. Note the selective loss of green fluorescence from the a-cell-originated nucleus in the diploid at 10 and 20 min. Time 0 indicates the time point shortly before cell fusion. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Quantitative analysis of the experiment shown in (C) (upper panel) or the averages of 6 independent experiments (lower panel). The relative fluorescence of GFP ( ), Cherry (

), Cherry ( ) and the calculated conversion of Net1CCG to Net1CC (

) and the calculated conversion of Net1CCG to Net1CC ( ) are plotted against the time (error bars, standard error (s.e.)). See also Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Movie 1. Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

) are plotted against the time (error bars, standard error (s.e.)). See also Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Movie 1. Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

To test the workflow for transferring interactions revealed by large-scale interaction experiments into single-cell analysis, we screened Net1CRU against an array of 382 different Nub fusions (Nub array) (Hruby et al, 2011). Among others Ubc9p, Cdc14p, and Fkh1p were identified as further Net1p-binding partners (Table I; Visintin et al, 1999). The interactions of Net1p with all three Nub fusions were subsequently analyzed by SPLIFF. The kinetic profiles of the Net1CCG conversions were very similar to the profile induced by Nub-Sir2p (Supplementary Figure 1). Nub-Cdc14p induced a slightly but significantly slower conversion of Net1CCG than Nub-Sir2p (Supplementary Figure 1; Supplementary Movie 2). Nub-Pea2p, a Nub-fusion that was not identified by the large-scale experiment, did also not interact in the SPLIFF analysis with Net1CCG (Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 1. Interaction partners of Net1p, Spa2p, and Stu2p identified by large-scale Split-Ub interaction screens.

| Cub fusions | Nub fusions |

|---|---|

| Net1p | Scc2p, Smt3p, Swi6p, Irr1p, Net1p, Fkh1p, Cdc14p, Fkh2p, Ubc9p |

| Spa2p | Kel1p, Hof1p, Ymr124wp, Spa2p, Bud14p, Sec4p, Pea2p |

| Stu2p | Spc24p, Bik1p, Spc72p, Bim1p, Kar3p, Dad1p, Dad3p, Stu2p, Clb4p, Kip2p, Kip3p, Kar9p |

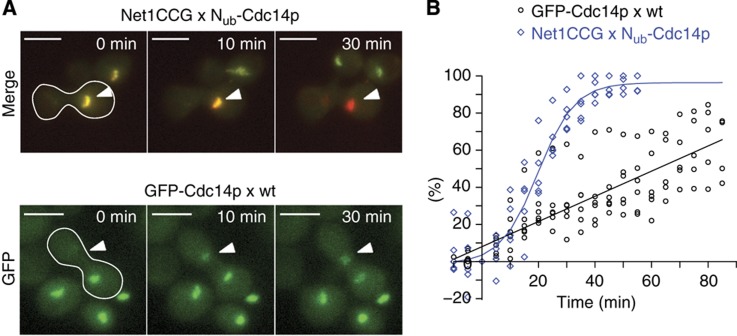

To identify the rate-limiting steps of these reactions, we compared the accumulation of GFP-Cdc14p in the nuclei of a-cells with the Nub-Cdc14p-induced Net1CCG conversion (Figure 3). In the first 10 min after mating, the kinetic profiles of both reactions were similar. However, whereas the best fit of the Net1CCG conversion is described by a sigmoid curve, the nuclear accumulation of GFP-CDC14p proceeded linear and consequently slower (Figure 3B). We conclude that the conversion of Net1CCG to Net1CC is not limited by the association rate of the fusion proteins and the subsequent Ub assembly and degradation of the attached GFP. The sigmoid shape indicates that the interaction between Cdc14p and Net1p is dynamic. Nub-Cdc14p exchanges binding partners and thereby catalytically converts Net1CCG into Net1CC.

Figure 3.

Comparison between Nub-Cdc14p-induced Net1CCG conversion and GFP-Cdc14p accumulation. (A) α-Cells expressing Nub-Cdc14p were mated with a-cells expressing Net1CCG and the conversion to Net1CC was recorded after mating (upper panel). Lower panel: α-cells expressing GFP-Cdc14p were mated with wild-type a-cells and the accumulation of the GFP signal was recorded in the a-cell-derived nucleus (white arrowhead) as fraction of total fluorescence measured shortly before cell fusion (t0). The white-framed cells indicate the diploid cells. (B) Pairwise comparison of best fits of independent experiments as shown in (A). Blue curve corresponds to conversion of Net1CCG and black curve to the accumulation of GFP-Cdc14. See also Supplementary Figure 1 and Supplementary Movie 2.

Interactions at the nuclear pore: slow exchange and transient interactions

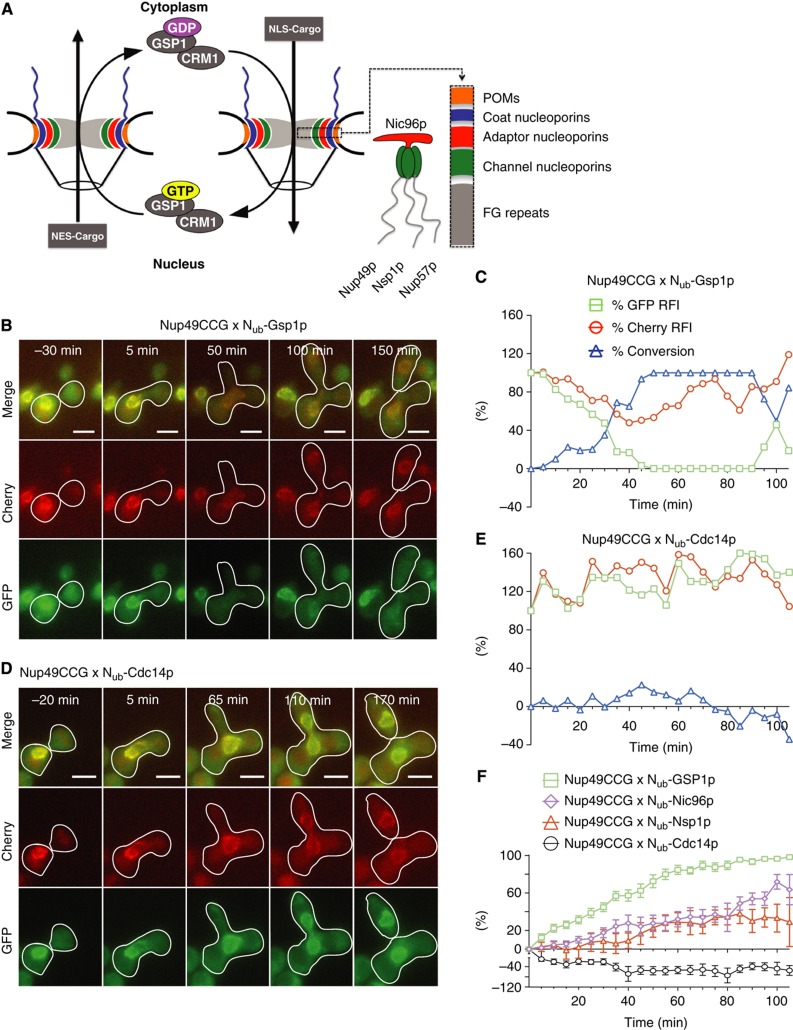

The nuclear pore complex of yeast consists of >30 different proteins that are organized into three different layers. Integral membrane proteins (POMs) anchor a ring of coat nucleoporins followed by adaptor nucleoporins. The adaptors position the channel nucleoporins to regulate the transfer of cargo between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Figure 4A; Aitchison and Rout, 2012). Nup49p and Nic96p together with Nsp1p and Nup57p form the Nic96p sub-complex (Figure 4A). Nic96p is a member of the adaptor nucleoporins whereas Nup49p, Nsp1p, and Nup57p belong to the FG repeat-bearing channel nucleoporins. FG repeats interact transiently with importins and exportins that are bound to cargo and the Ran-GTPase Gsp1p during their shuttle across the pore (Figure 4A; Aitchison and Rout, 2012). After mating, the nuclear membranes of the two yeast nuclei fuse and the nuclear pore complexes from both cells mix (Bucci and Wente, 1997). According to the growth rate of the co-expressing diploids Nup49CRU interacted strongly with Nub-Nup57p, -Nic96p, -Nsp1p, and only very weakly with Nub-Gsp1p (Supplementary Figure 2). We measured the kinetic profiles of these interactions with Nup49p as CCG fusion. The SPLIFF analysis of Nup49CCG visualized for the first time the interaction between a Ran-GTPase and a FG-repeat protein in a living cell (Figure 4B, C and F; Supplementary Movie 3). Nub-Gsp1p converted Nup49CCG much faster than the Nub fusions of Nic96p or Nsp1p (Figure 4F; Supplementary Figure 2; Supplementary Movie 4). The nuclear resident Nub-Cdc14p did not interact with Nup49CCG (Figure 4D and E). Contrary to the transport factors, constitutive members like Nsp1p or Nic96p are known to be stably incorporated into the nuclear pore complex (Rabut et al, 2004). We therefore surmise that the slow exchange of the unlabelled proteins against the corresponding Nub fusions of Nsp1p or Nic96p is rate limiting for the interaction with Nup49CCG. Notably, the interaction between Nup49CCG and its Nub-labelled interaction partners started only after nuclear fusion was completed (Supplementary Movie 4).

Figure 4.

Protein interactions at the nuclear pore. (A) Overview of the structure of the nuclear pore, the Nic96p sub-complex, and the nucleo-cytoplasmic traffic in yeast. (B) Selected frames of the time-lapse analysis of a cell (white frame) expressing Nup49CCG and Nub-Gsp1p after mating. The haploid cells are not framed. (C) Time-dependent relative fluorescence intensity of Cherry ( ), GFP (

), GFP ( ), and the calculated fraction of converted Nup49CC (

), and the calculated fraction of converted Nup49CC ( ) from the experiment shown in (B). Time 0 indicates the time point shortly before the fusion of the two nuclei. (D) As in (B) but showing a diploid cell expressing Nup49CCG and Nub-Cdc14p after mating. (E) Analysis as in (C) but of the experiment shown in (D). The nuclear protein Nub-Cdc14p does not interact. (F) Time-dependent change of the fractions of converted Nup49CC through interaction with Nub-Gsp1p (

) from the experiment shown in (B). Time 0 indicates the time point shortly before the fusion of the two nuclei. (D) As in (B) but showing a diploid cell expressing Nup49CCG and Nub-Cdc14p after mating. (E) Analysis as in (C) but of the experiment shown in (D). The nuclear protein Nub-Cdc14p does not interact. (F) Time-dependent change of the fractions of converted Nup49CC through interaction with Nub-Gsp1p ( ), Nub-Nic96p (

), Nub-Nic96p ( ), Nub-Nsp1p (

), Nub-Nsp1p ( ), and Nub-Cdc14p (

), and Nub-Cdc14p ( ). The averages of n=8 independent matings (error bars, s.e.) are shown. The expressions of the Nub fusions were induced by 100 μM copper. Scale bar, 5 μm. See also Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Movies 3 and 4. Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

). The averages of n=8 independent matings (error bars, s.e.) are shown. The expressions of the Nub fusions were induced by 100 μM copper. Scale bar, 5 μm. See also Supplementary Figure 2 and Supplementary Movies 3 and 4. Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

Interactions between components of the polar cortical domain: tracking interactions during the cell cycle

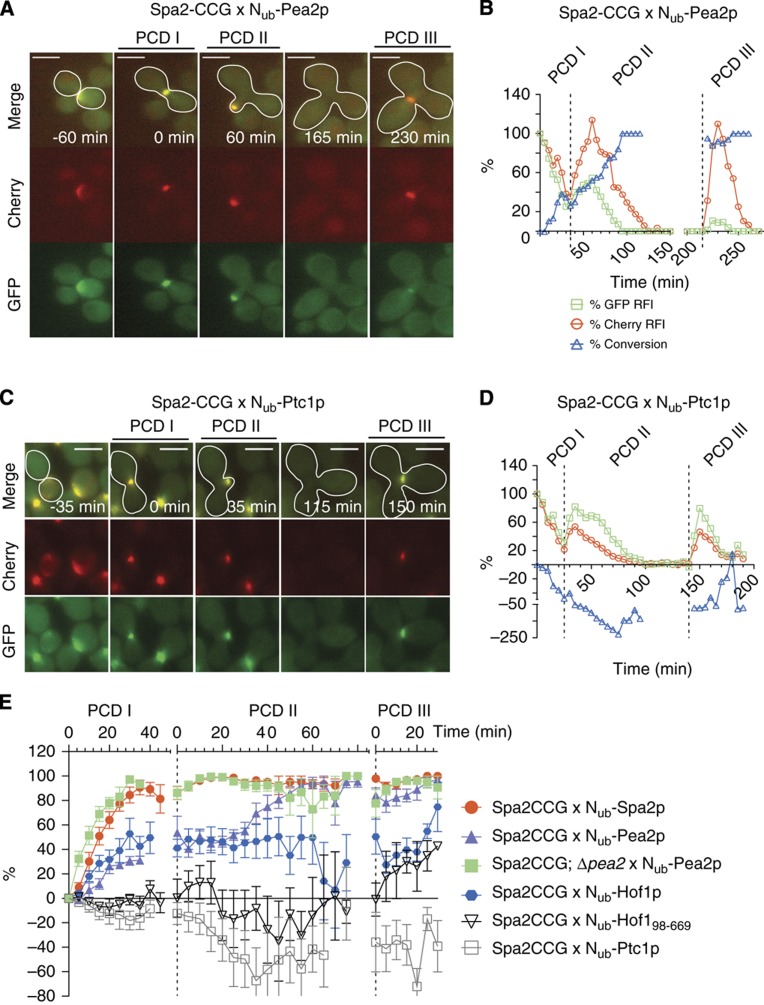

The proteins of the polar cortical domain (PCD) form a protein network below the plasma membrane. The composition of the PCD in yeast is not fully defined and highly dynamic (Gao et al, 2011). The PCD is located first at the mating projection (PCDI), later at the site of bud growth (PCDII), and finally at the site of cytokinesis (PCDIII). During these transitions, the components of the PCDs are dissolved before they are recruited to their new site (Figure 5A). Measuring the interactions between members of the PCD thus requires tracking of the CCG fusion in their different locations during the cell cycle. Spa2p is member of the polarisome complex that organizes the actin cytoskeleton at the PCD (Sheu et al, 1998). We first identified the pool of Nub-labelled interaction partners by mating a Spa2CRU expressing strain against the Nub array and selected a subset of those for single-cell analysis (Table I). Among the found binding partners was a further member of the polarisome Nub-Pea2p (Sheu et al, 1998). Time-lapse microscopy of the mated Spa2CCG and Nub-Pea2p expressing cells revealed for the first time that both proteins interact throughout the cell cycle (Figure 5A, B; Supplementary Movie 5). The specificity of the measurements was confirmed by co-expressing Spa2CCG and Nub-Ptc1p, a Nub fusion that, according to the large-scale analysis, does not bind to Spa2CRU (Figure 5C–E).

Figure 5.

SPLIFF analysis of the interactions between components of the polar cortical domain. (A) Selected frames of the time-lapse analysis of a cell (white frame) expressing Spa2CCG and Nub-Pea2p after mating. The haploid cells are not framed. PCDI indicates the stained region below the membrane of the shmoo tip, PCDII the region below the membrane of the growing bud, and PCDIII the region of cell separation. (B) Time-dependent relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) of Cherry ( ), GFP (

), GFP ( ), and the calculated fraction of converted Spa2CC (

), and the calculated fraction of converted Spa2CC ( ) of the experiment shown in (A). Time 0 indicates the time point shortly before the fusion of the cells. (C, D) As (A) and (B) but with diploid cells expressing Spa2CCG and Nub-Ptc1p after mating. The cytosolic protein Nub-Ptc1p does not interact with Spa2CCG. (E) Time-dependent change of converted Spa2CC through interaction with Nub-Spa2p (

) of the experiment shown in (A). Time 0 indicates the time point shortly before the fusion of the cells. (C, D) As (A) and (B) but with diploid cells expressing Spa2CCG and Nub-Ptc1p after mating. The cytosolic protein Nub-Ptc1p does not interact with Spa2CCG. (E) Time-dependent change of converted Spa2CC through interaction with Nub-Spa2p ( ), Nub-Pea2p (

), Nub-Pea2p ( ), and Nub-Pea2p in cells lacking the native Pea2p (

), and Nub-Pea2p in cells lacking the native Pea2p ( ), Nub-Hof1p (

), Nub-Hof1p ( ), Nub-Hof198–669 (

), Nub-Hof198–669 ( ), and Nub-Ptc1p (

), and Nub-Ptc1p ( ). Dashed lines separate the analyses of the subsequent PCDs. The averages of n=6 independent matings (error bars, s.e.) are shown. Scale bar, 5 μm. See also Supplementary Figure 3; Supplementary Movies 5–8. Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

). Dashed lines separate the analyses of the subsequent PCDs. The averages of n=6 independent matings (error bars, s.e.) are shown. Scale bar, 5 μm. See also Supplementary Figure 3; Supplementary Movies 5–8. Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

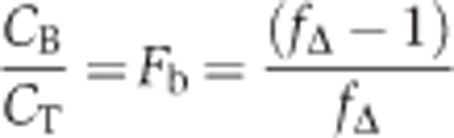

Spa2p forms homo-oligomers (Table I). Our SPLIFF analysis revealed that this reaction occurred much faster than the Spa2p-Pea2p heteromerization (Figure 5E; Supplementary Figure 3; Supplementary Movie 6). Why is the Spa2p-Pea2p interaction slower? We presumed that the continuous presence of the unlabelled Pea2p in the polarisome might effectively hinder Nub-Pea2p from binding and converting Spa2CCG. Consequently, cells lacking unlabelled Pea2p should display a faster interaction. Consistent with our hypothesis, we observed a 5.3-fold increase in the rate of Nub-Pea2p induced Spa2CCG conversion upon deleting the chromosomal PEA2 in the Spa2CCG expressing a-cells (Figure 5E; Supplementary Figure 3; Supplementary Movie 7). The ratio of the initial rates of conversion RCiPEA2 to RCiΔpea2 (Δf=5.3) provides a quantitative measure (Supplementary Figure 3). By using simplifying assumptions, we calculated the fraction of bound Spa2p (Fb) by Fb=(Δf−1)/Δf. Based on this calculation, we estimate that only 19% of the Spa2CCG molecules in wild-type cells are free to react with Nub-Pea2p. The remaining 81% (Fb) of the binding sites are occupied by endogenous Pea2p.

We identified Hof1p, a member of the cytokinesis machinery, as a new ligand of Spa2p (Table I) (Lippincott and Li, 1998; Meitinger et al, 2011). The SPLIFF analysis revealed that Hof1p already interacted with Spa2p at the PCDI during cell fusion. Furthermore, the kinetic profile of the interaction between Spa2CCG and Nub-Hof1p differed strikingly from the profile of the Spa2p/Pea2p interaction in tracing interactions during fusion and cytokinesis but not during bud growth (Figure 5E; Supplementary Movie 8). An allele of HOF1 lacking the N-terminal FCH domain (Nub-Hof198–669) added an interesting mechanistic detail to the understanding of this protein interaction. In contrast to the full-length protein, Nub-Hof198–669 converted Spa2CCG only during cytokinesis but not during cell fusion (Figure 5E). The results thus allude to different modes and degrees of interaction between Hof1p and Spa2p during the three phases of polar growth.

Mapping the cellular space of protein–protein interactions

Many proteins simultaneously occupy different locations in the cell. Each of these locations might reflect an altering set of binding partners. We examined the cellular distributions of four different protein interactions to demonstrate the spatial resolution of SPLIFF.

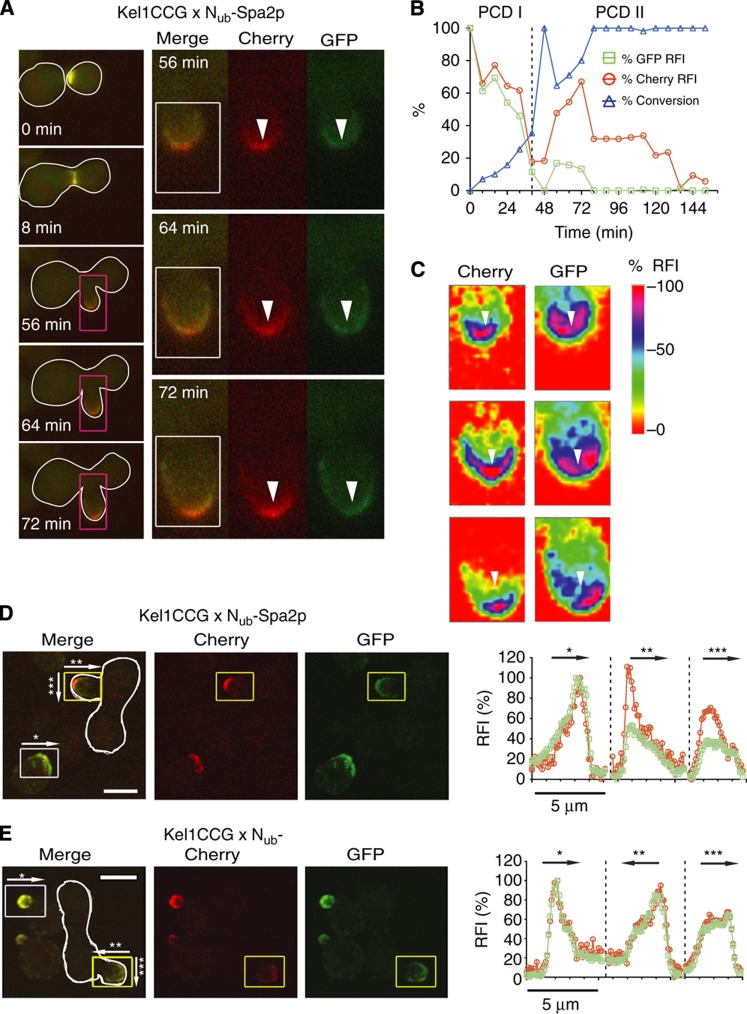

The Nub fusion of Kel1p was found as interaction partner of Spa2CRU (Table I). Kel1p is involved in cell fusion during mating (Philips and Herskowitz, 1998). Kel1CCG is spread across the entire bud during its growth (Figure 6A). To specify the regions of Kel1p–Spa2p interaction, we mated Kel1CCG- with Nub-Spa2p expressing cells. Time-lapse analysis of the diploids revealed that the interaction occurs not only during cell fusion but also during bud growth (Figure 6A and B). We analyzed the spatial distribution of the red and green fluorescence in medium-sized buds (Figure 6C–E). Both intensities matched closely at the base of the bud yet segregated at its tip (Figure 6C–E). The reconstituted differential interaction maps describe a gradient in the ratio of red to green fluorescence that peaks at the bud tip and trails off toward the mother cell (Figure 6D and E). This distribution very probably corresponds with a gradient of interactions caused by the unequal distribution of Spa2p and Kel1p across the bud (Figures 5A and 6A).

Figure 6.

Map of the cellular location of the Spa2p/Kel1p interaction. (A) Left panel: Selected frames of the time-lapse analysis of a diploid cell (white frame) expressing Kel1CCG and Nub-Spa2p after mating. The distribution of Kel1CCG and Kel1CC is shown. Right panel: Blow-ups of the purple-framed buds showing the distribution of GFP (Kel1CCG) and Cherry (Kel1CCG+Kel1CC) at the indicated times. (B) Time-dependent change of the relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) of Cherry ( ), GFP (

), GFP ( ), and the calculated fraction of converted Kel1CC (

), and the calculated fraction of converted Kel1CC ( ) in the experiment shown in (A). Time 0 indicates the time point shortly before cell fusion. (C) Colour-coded maps of the RFIs of cherry (Kel1CCG+Kel1CC) and GFP (Kel1CCG) obtained from the area within the white squares of (A), right panel. White arrows point to identical regions of the bud in the two channels and mark regions of relative depletion of GFP (Kel1CCG). (D) Left panels: 3D reconstructions of confocal images from GFP, Cherry and merged channels of yeast cells expressing Kel1CCG, or Kel1CCG and Nub-Spa2p after mating (white frame). Right panels show the profiles of the relative GFP and Cherry intensities from the yellow- (diploid) and white-framed (haploid) buds obtained by summing over all fluorescence intensities encountered orthogonal to the direction of the respective arrows. Arrow *: across the tip of the bud of haploid cells. Arrow **: from the tip to the base of the bud of diploid cells. Arrow ***: across the tip of the bud of diploid cells. (E) Analysis as in (D) but of cells expressing Kel1CCG and a Nub fusion not binding to Kel1p. Scale bar, 5 μm. Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

) in the experiment shown in (A). Time 0 indicates the time point shortly before cell fusion. (C) Colour-coded maps of the RFIs of cherry (Kel1CCG+Kel1CC) and GFP (Kel1CCG) obtained from the area within the white squares of (A), right panel. White arrows point to identical regions of the bud in the two channels and mark regions of relative depletion of GFP (Kel1CCG). (D) Left panels: 3D reconstructions of confocal images from GFP, Cherry and merged channels of yeast cells expressing Kel1CCG, or Kel1CCG and Nub-Spa2p after mating (white frame). Right panels show the profiles of the relative GFP and Cherry intensities from the yellow- (diploid) and white-framed (haploid) buds obtained by summing over all fluorescence intensities encountered orthogonal to the direction of the respective arrows. Arrow *: across the tip of the bud of haploid cells. Arrow **: from the tip to the base of the bud of diploid cells. Arrow ***: across the tip of the bud of diploid cells. (E) Analysis as in (D) but of cells expressing Kel1CCG and a Nub fusion not binding to Kel1p. Scale bar, 5 μm. Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

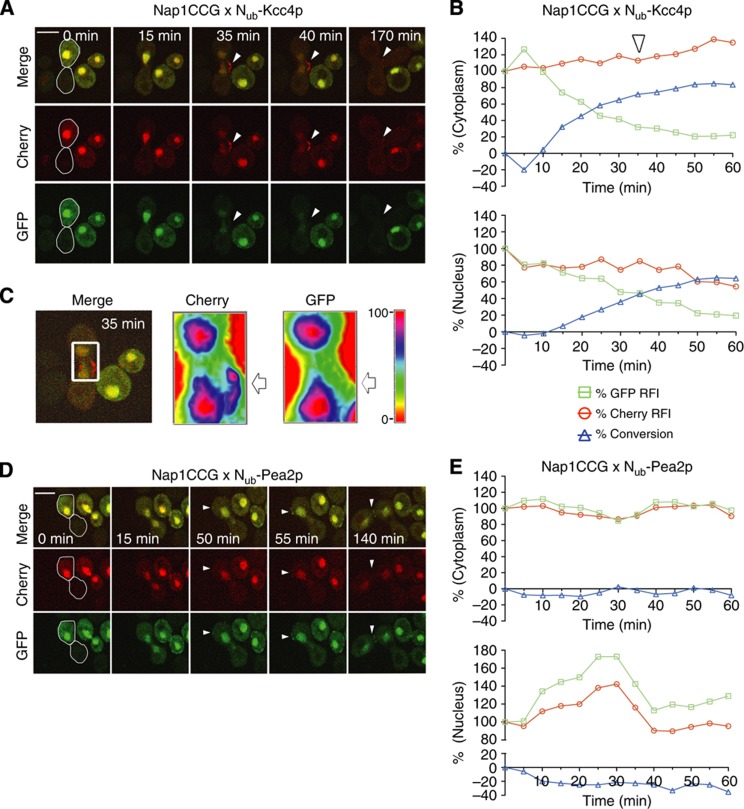

Nap1p is a multifunctional protein that is involved in the transport and assembly of histones and the formation of the septin ring at the bud neck of the cells (Mortensen et al, 2002; Ohkuni et al, 2003). Nap1p is localized in the cytosol, the nucleus, and the bud neck. We recently confirmed Nub-Kcc4p as binding partner of Nap1CRU (Hruby et al, 2011). Kcc4p is a septin-localized protein kinase (Barral et al, 1999; Okuzaki and Nojima, 2001). To find out exactly when and where the interaction between Nap1p and Kcc4p occurs, we monitored the Nub-Kcc4p-induced conversion of Nap1CCG in the cytosol as well as in the nucleus. The interaction started immediately after cell fusion (Figure 7A and B). The slower decrease in nuclear versus cytosolic green fluorescence indicated that Kcc4p interacts with Nap1p primarily in the cytosol (Figure 7B; Supplementary Figure 4). Continuous time-lapse analysis of Nap1CCG identified at a later time point during early bud formation a red fluorescent zone devoid of green fluorescence beneath the incipient bud site (Figure 7A and C; Supplementary Movie 9). This region of preferred complex formation contrasted with the nucleus as well as with the cytosol as two compartments of comparatively weak Nap1p-Kcc4p interaction activity (Figure 7C). Fifty minutes after mating a decrease in the nuclear Cherry signal might indicate a trapping of Nap1CCG in the cytosol through the continuous co-expression of Nub-Kcc4p (Figure 7B). Nub-Pea2p is also concentrated at the incipient bud site but does not interact with Nap1CRU. Consequently, Nub-Pea2p did not induce a similar dissociation of red from green fluorescence in Nap1CCG-expressing cells (Figure 7D and E).

Figure 7.

Dynamic map of the Nap1p/Kcc4p interaction. (A) Selected frames of the time-lapse analysis of a diploid cell (white frame) expressing Nap1CCG and Nub-Kcc4p after mating. White arrowheads point the region of high interaction activity at the site of a newly emerging bud. (B) Time-dependent change of the relative fluorescence intensity (RFI) of Cherry ( ), and GFP (

), and GFP ( ), as well as the calculated fraction of converted Nap1CC (

), as well as the calculated fraction of converted Nap1CC ( ) in the experiment shown in (A). The analysis distinguishes between the cytoplasmic (upper panel) and the nuclear-localized Nap1CCG (lower panel). The cytoplasmic fluorescence is defined as the difference between total cellular and nuclear fluorescence. Note that the reaction occurs faster in the cytosol than in the nucleus (see also Supplementary Figure 4). The white arrowhead indicates the time of the first appearance of the region of high interaction activity in the emerging bud. (C) Colour-coded map of the RFI of Cherry (Nap1CCG+Nap1CC) and GFP (Nap1CCG) in the white-boxed cell (left panel) in the experiment shown in (A) at 35 min. White arrows point to the emerging bud. (D, E) Analysis exactly as in (A, B) but with cells co-expressing Nap1CCG and Nub-Pea2p. Nub-Pea2p does not interact with Nap1CCG. White arrowheads point to the emerging bud that is not preferentially stained by Cherry. Expressions of the Nub fusions were induced by 100 μM copper. Scale bar, 5 μm. See also Supplementary Figure 4 and Supplementary Movie 9. Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

) in the experiment shown in (A). The analysis distinguishes between the cytoplasmic (upper panel) and the nuclear-localized Nap1CCG (lower panel). The cytoplasmic fluorescence is defined as the difference between total cellular and nuclear fluorescence. Note that the reaction occurs faster in the cytosol than in the nucleus (see also Supplementary Figure 4). The white arrowhead indicates the time of the first appearance of the region of high interaction activity in the emerging bud. (C) Colour-coded map of the RFI of Cherry (Nap1CCG+Nap1CC) and GFP (Nap1CCG) in the white-boxed cell (left panel) in the experiment shown in (A) at 35 min. White arrows point to the emerging bud. (D, E) Analysis exactly as in (A, B) but with cells co-expressing Nap1CCG and Nub-Pea2p. Nub-Pea2p does not interact with Nap1CCG. White arrowheads point to the emerging bud that is not preferentially stained by Cherry. Expressions of the Nub fusions were induced by 100 μM copper. Scale bar, 5 μm. See also Supplementary Figure 4 and Supplementary Movie 9. Source data for this figure is available on the online supplementary information page.

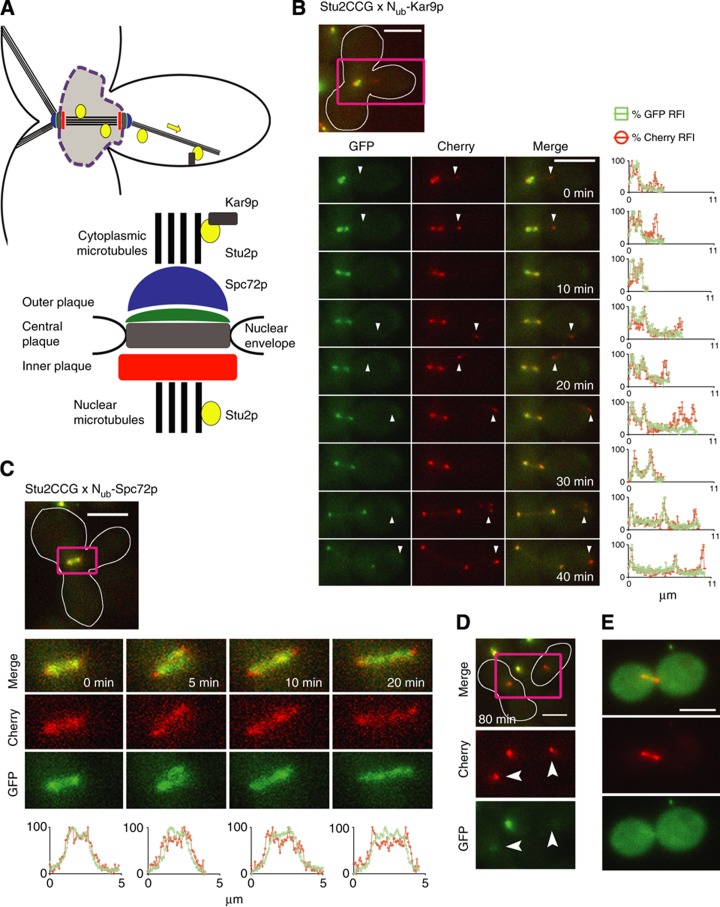

Stu2p is a microtubule-binding protein that is associated with the cytosolic and nuclear portion of the spindle pole body (SPB), and the nuclear, and astral microtubules (Figure 8A) (Usui et al, 2003; Al-Bassam et al, 2006; Kitamura et al, 2010; Winey and Bloom, 2012). The large-scale Split-Ub assay of Stu2CRU identified among others the known binding partner Kar9p, and Spc72p (Table I) (Miller et al, 2000; Liakopoulos et al, 2003; Usui et al, 2003). Mating of cells expressing Stu2CCG and the corresponding Nub-fusion proteins allowed us to dissect the microtubule structures into zones of differential Stu2p interaction activities (Figure 8B and C). The interaction between Stu2CCG and its two Nub-labelled binding partners started immediately upon nuclear fusion and the accompanying alignment of the two SPBs. Later during the cell cycle the unequal distribution of the red and green fluorescence across the Stu2CCG-stained microtubules clearly identified the tip of the astral microtubules as preferred site of Stu2p–Kar9p interaction (Figure 8B; Supplementary Movie 10). In contrast, time-lapse analysis of the cells co-expressing Stu2CCG and Nub-Spc72p revealed a preferential conversion of Stu2CCG into Stu2CC at both tips of the spindle (Figure 8C). One hour later a small fraction of green fluorescent Stu2CCG still remained in the mother whereas the SPB of the daughter cell was stained completely red (Figure 8D). Mated cells that were cultivated for several generations displayed a complete conversion of Stu2CCG into Stu2CC (Figure 8E).

Figure 8.

Dynamic map of the interactions of Stu2p. (A) Overview of the microtubule-based structures in yeast. (B) Upper panel: Merge of GFP and Cherry channels of a Stu2CCG- and Nub-Kar9p-expressing diploid cell (white frame). Purple rectangle indicates the section shown in the frames of the time-lapse analysis of the lower left panel. Lower left panel: Selected frames of the GFP, Cherry, and the merged channels of the time-lapse analysis of a diploid cell expressing Stu2CCG and Nub-Kar9p after mating. Lower right panel: Time- and position-dependent change of the RFIs of Cherry (Stu2CCG+StuCC) ( ) and GFP (Stu2CCG) (

) and GFP (Stu2CCG) ( ). Values are plotted along the distance of the microtubules connecting both SPBs, and the SPBs with the tip of the microtubules in the bud. The tip of the bud-directed microtubule is a region of preferred interaction between Stu2CCG and Nub-Kar9p. (C) Upper panel: Merge of GFP and Cherry channels of a Stu2CCG- and Nub-Spc72p-expressing diploid cell (white frame) after mating. The purple rectangle indicates the section shown in the frames of the time-lapse analysis of the lower panel. Lower panel: Time- and position-dependent change of the RFIs of Cherry (

). Values are plotted along the distance of the microtubules connecting both SPBs, and the SPBs with the tip of the microtubules in the bud. The tip of the bud-directed microtubule is a region of preferred interaction between Stu2CCG and Nub-Kar9p. (C) Upper panel: Merge of GFP and Cherry channels of a Stu2CCG- and Nub-Spc72p-expressing diploid cell (white frame) after mating. The purple rectangle indicates the section shown in the frames of the time-lapse analysis of the lower panel. Lower panel: Time- and position-dependent change of the RFIs of Cherry ( ), and GFP (

), and GFP ( ). Values are plotted along a line connecting the two SPBs. Both ends of the structure mark sites of preferred Stu2CCG/Spc72p interaction. (D) Same cell as in (C) but after cytokinesis has already occurred. Arrowheads indicate the SPBs of mother and daughter cell (white frame). The SPB of the mother cell retains a small amount of Stu2CCG. (E) Stu2CCG- and Nub-Spc72p-expressing diploid cells after cultivation for several generations. Scale bar, 5 μm. See also Supplementary Movie 10.

). Values are plotted along a line connecting the two SPBs. Both ends of the structure mark sites of preferred Stu2CCG/Spc72p interaction. (D) Same cell as in (C) but after cytokinesis has already occurred. Arrowheads indicate the SPBs of mother and daughter cell (white frame). The SPB of the mother cell retains a small amount of Stu2CCG. (E) Stu2CCG- and Nub-Spc72p-expressing diploid cells after cultivation for several generations. Scale bar, 5 μm. See also Supplementary Movie 10.

Discussion

Due to their indifference in regard to order, location, and timing, large-scale protein interaction networks are still a largely untapped resource of information that waits to be fully exploited by cell biologist (Alexander et al, 2009; Kim et al, 2006; Przytycka et al, 2010; Vidal et al, 2011; Deeds et al, 2012). Up to now dynamic and spatial features of protein interactions could only be revealed by fluorescence resonance energy transfer between two fluorescently tagged proteins or fluorescence cross correlation spectroscopy of two freely diffusing cytosolic proteins (Bacia and Schwille, 2007; Slaughter et al, 2011). However, both methods require careful optimizations before a positive hit from one of the high-throughput studies can be visualized as protein interaction in the cell. A transfer of large-scale interaction data into the analysis of their dynamic and spatial aspects is thus hardly possible (Lowder et al, 2011). We routinely achieved these transitions by replacing a large-scale compatible version of the Split-Ub technique by SPLIFF to subsequently probe the detected interactions with high spatial and temporal resolution in living cells.

Among the further advantages of SPLIFF is the nearly instantaneous detection of binding once the Nub and Cub fusions are free to interact. The Cherry signal that remains at the protein identifies the place of interaction and serves as internal reference for the decrease in GFP signal. The GFP signal reflects the fraction of uncut Cub-fusion proteins and by extrapolation the unbound fraction of the protein with regard to its Nub-labelled binding partner. As the cleavage of GFP is the temporally delayed consequence of interaction, the localization of the Cherry-Cub fusion protein can only be an approximation of where the interaction has originally occurred. To set closer limits for the preferred sites of interaction or for visualizing gradients of interactions across the cell, it is thus obligatory to analyze the signals of both, the bound and unbound fraction of the Cub fusion. A realistic interpretation of the relative green and red fluorescence intensities (FIs) further necessitates a continuous online detection once Nub and Cub fusions encounter each other. We used cell fusion by mating as a controlled way of mixing the two fusion proteins. The procedure unambiguously defines the start of the reaction and allows tracking it throughout the cell cycle. This feature also enhances the reproducibility of the measurements as averaging different single-cell measurements with slightly shifted cell-cycle phases might obscure specific aspects of the interactions. For example, any static or unsynchronized analysis would have missed our discovery that the interaction between Hof1p and Spa2p is restricted to cell fusion and cell separation but does not occur during bud growth. Together with Sho1p, Hof1p is now the second member of the HICS complex that is involved in cell fusion and cytokinesis (Labedzka et al, 2012). The question whether further members of the cytokinesis network also participate in cell fusion as part of identical or different protein complexes can now be systematically investigated by SPLIFF.

The feature of simultaneously detecting bound and unbound fraction was instrumental in localizing the interaction between the microtubule-nucleator Stu2p and the component of the SPB Spc72p. The prevalence of unbound Stu2CCG at the nuclear microtubules, the high fraction of bound Stu2CC at both tips of the spindle, and the known localization of Spc72p strongly suggests the cytosolic part of the SPB as the preferred site of Stu2p–Spc72p interaction. As the converted Stu2CC dissociated from Nub-Spc72p its newly acquired localizations during later time points blurred the assignment of its interaction to a specific place in the cell. We therefore postulate that the subsequent increase in the Cherry signal at the other Stu2p-containing structures was most likely due to the dynamic exchange of Stu2CCG by Stu2CC that was originally generated by Nub-Spc72p at the SPB. However, without additional knowledge or experimentation our analysis could not strictly exclude that a certain fraction of these signals might have been caused by a minor population of Nub-Spc72p localized at these sites specifically during the later phases of the cell cycle. Ultimately, once conversion of Stu2CCG into Stu2CC was nearly completed the Stu2p-containing structures were uniformly stained by Cherry and a detection of interaction no longer feasible.

The moderate affinity between Nub and Cub might stabilize transient or weak protein complexes by reducing the rate of their dissociation (Müller and Johnsson, 2008). Applying the rate of CCC to CG conversion and not the CCG/CC ratio as the preferred measure to specify the cellular place and duration of a certain interaction should avoid that this temporal trapping might interfere with the spatial and temporal resolution of SPLIFF.

Our studies thus defined the rapid and continuous detection of interaction, the detection of the unbound fraction, and the ability to control the start of the reaction as three requirements for the accurate SPLIFF analysis of protein interactions. Split-protein sensors lacking any of these features call for an even more deliberate interpretation with regard to localizing and timing a certain protein interaction. For example, the fluorescence signal generated upon reconstitution of Split-GFP (BiFC) might simply reflect the localization of the binding partner with the strongest localization signal and not necessarily the cellular site of their interaction (Kerppola, 2006; Stynen et al, 2012).

As the conversion of CCG to CC is irreversible, the continuous interaction between the Nub- and Cub-coupled fusion proteins will deplete the pool of CCG substrate and reduces the rate of its conversion. As a consequence, quantitative differences in the rate of conversion do not automatically correspond with quantitative differences in the dynamics of the underlying protein interaction. Despite this and other limitations of SPLIFF in exploring quantitative aspects of protein interactions, we propose that the calculated occupancy (Fb) of a protein is a useful quantitative reference for classifying protein complexes. For example, the Fb of 81% indicates that the Spa2p/Pea2p complex is much more stable than the Net1p/Fkh1p complex as the absence of unlabelled Fkh1p revealed no significant increase in the respective RCi of Net1CCG (Supplementary Figure 1; Ghaemmaghami et al, 2003).

The application of SPLIFF in higher eukaryotes is a very realistic perspective, as all essential components of this technique are also functional in these cells (Pratt et al, 2007).

Materials and methods

Time-lapse microscopy

Time-lapse experiments were carried out using a DeltaVision fluorescence microscope (Applied Precision) provided with a steady-state heating chamber and equipped with a mercury arc lamp and a camera CoolSNAP HQ2-ICX285 (Photometrics). In all cases a 100x NA 1.4 UPlanSApo oil immersion objective (Olympus) was used. Unless otherwise stated, images at 0.8 μm intervals for a 4-section z stack were collected in 5 min intervals on three channels: Brightfield, GFP (excitation 470/40 nm and emission 525/50), and Cherry (excitation 572/35 nm and emission 632/60). The CCD capture time was adapted to the intensity of GFP and Cherry signal in every construct to reduce bleaching and phototoxicity.

Confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy was conducted using An Axio Observer Z.1 Spinning Disc microscope (Zeiss). Images were acquired under the control of the AxioVision 4.8.2 software (Zeiss) as Z series with 15–20 twenty slices. The distance between two Z slices was set to 260 nm. For image acquisition, a Plan-APOCHROMAT 63 × /1.4 Oil DIC ∞/0.17 objective and 1 × 1 binning was used. The camera gain was set to 1. For excitation of GFP or Cherry, a 488-nm diode laser at 80% laser power or a 561-nm diode laser at 100% laser power was used.

Fluorescence quantification and analysis

All files generated by the microscope software (Resolve3D softWoRx-Acquire Version: 4.0.0 Release 16) were processed and analyzed with ImageJ 1.45s (US National Institutes of Health; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/download.html). Z stacks were projected onto two-dimensional images. In order to quantify the fluorescence over time, we selected regions of interest (ROI) and a region within the cell that could serve as background for the quantification. In experiments where the CCG fusion was distributed throughout the cell a section from a haploid Nub-fusion-expressing cell occupying the same field was used as reference. To quantify localization-dependent protein interactions, we analyzed the spatial fluorescence profiles of the structures of interest. Z stacks were projected to two-dimensional images. The intensity variations of the GFP and Cherry Channels were followed on a chosen path or across a certain area of the cell using either ImageJ Plot Profile tool or Interactive 3D surface plot tool, respectively.

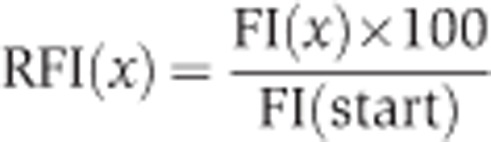

To obtain the relative fluorescence intensities (RFIs) of each channel, we first calculated the FI by:

to then calculate the RFIs by:

|

(loc) specifies the signal of the ROI areas and (back) the signal derived from the background areas. In time-dependent interaction experiments, (x) represents time. FI(start) represents the FIs shortly before the fusion of the cells. The RFIs of both channels were then used to calculate the extent of the interaction (FD) as measured by conversion of the CCG fusion to the CC Fusion by:

|

In localization-dependent interactions, (x) represents distance along the chosen path. In static localization-dependent interactions, FI(start) represents the maximal value of the analogous structure in a haploid CCG-expressing strain, which resides in the same field as the investigated diploid. In the time- and localization-dependent interactions of Stu2CCG, FI(start) represents the maximal intensities of both channels for each time frame shown.

Image preparation for publication

Images were prepared for publication with Acrobat Illustrator (Adobe) using linear contrast and intensity adjustments. When needed, DeltaVision fluorescence microscope images were deconvoluted using the software Resolve3D (softWoRx-Acquire Version: 4.0.0 Release 16). 3D reconstructions were obtained from Z stacks acquired by confocal microscopy using ImageJ 3D projection tools.

Interaction analysis by cell growth

Large scale Split-Ub assays were performed as described (Hruby et al, 2011; Dünkler et al, 2012). Measuring interactions between individual Nub- and Cub-fusion proteins by spotting yeast cells expressing both fusions onto 5-FOA and SD Ura-containing media was essentially as described (Eckert and Johnsson, 2003).

Single-cell interaction analysis

The CCG- and Nub-fusion-expressing a- and α-cells were separately incubated in SD medium at 30°C overnight. If not indicated otherwise cells were diluted into fresh medium without copper and grown to an OD600 of 0.6–1. After mixing equal amounts of the a- and α-cells (between 0.5 and 0.75 ml each), the culture was immediately spun down, and resuspended in 50 μl of SD medium. 3 μl of this suspension was immobilized by fixing a coverslide with parafilm strips on a custom-designed glass slide containing solid, non-fluorescent agar-SD without copper if not indicated otherwise. The slide was immediately incubated at 30°C under the microscope. Pictures were taken after 45–75 min of incubation when the first zygote formations became visible.

Construction of Nub- and Cub-fusion genes and other molecular manipulations

Nub- and Cub-fusion genes were constructed as described (Hruby et al, 2011; Dünkler et al, 2012). Gene deletions were performed by PCR-based methods as described (Janke et al, 2004).

The switch from the CRU to the CCG module was achieved by cloning the same PCR product used for the construction of the respective CRU fusion in front the CCG cassettes on a pRS306 or pRS304 vector. Linearization of the obtained plasmids with restriction enzymes cutting only once in the amplified sequences of the ORFs of the respective genes and homologous recombination after transformations of the yeast were as described (Dünkler et al, 2012). Successful recombination was verified by colony-PCR. Descriptions of the used constructs and yeast strains can be found in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Growth conditions, yeast strains, and genetic methods

Culture media and yeast genetic methods were performed following standard protocols (Dünkler et al, 2012). Media for the Split-Ub interaction assay contained 1 mg/ml 5-FOA. Yeast strains JD47, JD53, and JD51 are as described (Dünkler et al, 2012).

Calculating the initial rates of conversion

By plotting the relative decrease in GFP fluorescence FD we calculated by linear regression the initial rates of conversion (RCi) for the first 15 min of the reaction.

Calculating the ligand-bound fraction Fb

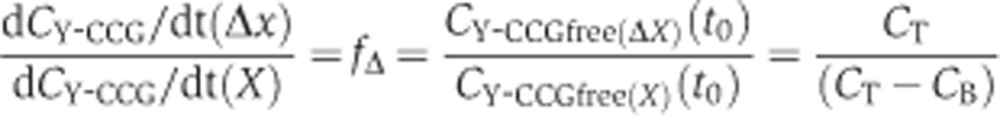

We assumed that the conversion of Y-CCG fusion into the Y-CC fusion after mating with the Nub-X expressing strain is described by a bimolecular reaction where the rate of conversion is given by

|

Y-CCCGfree is the concentration of unbound Y-CCG-fusion and CNub-Xfree the concentration of unbound Nub-X. k is the rate constant of the reaction and a complex composite of a mix of different reactions including among others the rate of Nub and Cub reassembly, the cleavage rate by the ubiquitin-specific proteases, the diffusion constants.

We assume that shortly after cell fusion k and CNub-Xfree are very similar if not identical in the two diploids that were derived by mating of the Nub-X-expressing strain with a Y-CCG-fusion-expressing strain where the gene X was either deleted (Δx) or not (X). It then follows that the quotient of the initial rates:

|

CT is the sum of the concentrations of free and bound Y-CCG fusion whereas CB is the concentration of Y-CCG fusion bound to X.

|

dCY-CCG/dt(Δx) and dCY-CCG/dt(X), the RCis of both reactions were derived by calculating a linear regression of the first 15 min after the reaction has started. The averages from at least four different independent measurements were taken. An analysis of the two reactions was only performed when the curves of the kinetic profiles were significantly different.

Statistical evaluation and curve fitting of the experimental data

Curve fitting was performed in R version 2.15.1 ( http://www.R-project.org) by minimizing the least squares deviation of a set of regression functions to the data. The best fitting function was determined by the Akaike information criterion. For comparison of two groups, the sum of the residual sum of squares of the individual regressions is then compared to that of the regression for the combined data using the F-test (Motulsky and Ransnas, 1987).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Johnsson laboratory for discussions and constructs, and Judith Müller and Kai Johnsson for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the BMBF Initiative SysTec (0315690B) and by the BMBF Initiative GerontoSys2 (SyStaR, 03158 94A).

Author contributions: DM with contributions of AD and JN performed and analyzed the experiments. HK and KJ performed the statistical evaluation and curve fitting of the data. NJ, DM, and AD designed the research. NJ wrote the manuscript with contributions of all other authors.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Aitchison JD, Rout MP (2012) The yeast nuclear pore complex and transport through it. Genetics 190: 855–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Bassam J, van Breugel M, Harrison SC, Hyman A (2006) Stu2p binds tubulin and undergoes an open-to-closed conformational change. J Cell Biol 172: 1009–1022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander RP, Kim PM, Emonet T, Gerstein MB (2009) Understanding modularity in molecular networks requires dynamics. Sci Signal 2: pe44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacia K, Schwille P (2007) Practical guidelines for dual-color fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy. Nat Protoc 2: 2842–2856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral Y, Parra M, Bidlingmaier S, Snyder M (1999) Nim1-related kinases coordinate cell cycle progression with the organization of the peripheral cytoskeleton in yeast. Genes Dev 13: 176–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitkreutz A, Choi H, Sharom JR, Boucher L, Neduva V, Larsen B, Lin ZY, Breitkreutz BJ, Stark C, Liu G, Ahn J, Dewar-Darch D, Reguly T, Tang X, Almeida R, Qin ZS, Pawson T, Gingras AC, Nesvizhskii AI, Tyers M (2010) A global protein kinase and phosphatase interaction network in yeast. Science 328: 1043–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucci M, Wente SR (1997) In vivo dynamics of nuclear pore complexes in yeast. J Cell Biol 136: 1185–1199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeds EJ, Krivine J, Feret J, Danos V, Fontana W (2012) Combinatorial complexity and compositional drift in protein interaction networks. PLoS ONE 7: e32032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dünkler A, Müller J, Johnsson N (2012) Detecting protein-protein interactions with the split-ubiquitin sensor. Methods Mol Biol 786: 115–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert JH, Johnsson N (2003) Pex10p links the ubiquitin conjugating enzyme Pex4p to the protein import machinery of the peroxisome. J Cell Sci 116: 3623–3634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao JT, Guimera R, Li H, Pinto IM, Sales-Pardo M, Wai SC, Rubinstein B, Li R (2011) Modular coherence of protein dynamics in yeast cell polarity system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 7647–7652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin AC, Bosche M, Krause R, Grandi P, Marzioch M, Bauer A, Schultz J, Rick JM, Michon AM, Cruciat CM, Remor M, Höfert C, Schelder M, Brajenovic M, Ruffner H, Merino A, Klein K, Hudak M, Dickson D, Rudi T et al. (2002) Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature 415: 141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaemmaghami S, Huh WK, Bower K, Howson RW, Belle A, Dephoure N, O'Shea EK, Weissman JS (2003) Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature 425: 737–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruby A, Zapatka M, Heucke S, Rieger L, Wu Y, Nussbaumer U, Timmermann S, Dunkler A, Johnsson N (2011) A constraint network of interactions: protein-protein interaction analysis of the yeast type II phosphatase Ptc1p and its adaptor protein Nbp2p. J Cell Sci 124: 35–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janke C, Magiera MM, Rathfelder N, Taxis C, Reber S, Maekawa H, Moreno-Borchart A, Doenges G, Schwob E, Schiebel E, Knop M (2004) A versatile toolbox for PCR-based tagging of yeast genes: new fluorescent proteins, more markers and promoter substitution cassettes. Yeast 21: 947–962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson N, Varshavsky A (1994) Split ubiquitin as a sensor of protein interactions in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 10340–10344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerppola TK (2006) Design and implementation of bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays for the visualization of protein interactions in living cells. Nat Protoc 1: 1278–1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PM, Lu LJ, Xia Y, Gerstein MB (2006) Relating three-dimensional structures to protein networks provides evolutionary insights. Science 314: 1938–1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura E, Tanaka K, Komoto S, Kitamura Y, Antony C, Tanaka TU (2010) Kinetochores generate microtubules with distal plus ends: their roles and limited lifetime in mitosis. Dev Cell 18: 248–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan NJ, Cagney G, Yu H, Zhong G, Guo X, Ignatchenko A, Li J, Pu S, Datta N, Tikuisis AP, Punna T, Peregrín-Alvarez JM, Shales M, Zhang X, Davey M, Robinson MD, Paccanaro A, Bray JE, Sheung A, Beattie B et al. (2006) Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 440: 637–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labedzka K, Tian C, Nussbaumer U, Timmermann S, Walther P, Müller J, Johnsson N (2012) Sho1p connects the plasma membrane with proteins of the cytokinesis network via multiple isomeric interaction states. J Cell Sci. 25: 4103–4113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liakopoulos D, Kusch J, Grava S, Vogel J, Barral Y (2003) Asymmetric loading of Kar9 onto spindle poles and microtubules ensures proper spindle alignment. Cell 112: 561–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippincott J, Li R (1998) Dual function of Cyk2, a cdc15/PSTPIP family protein, in regulating actomyosin ring dynamics and septin distribution. J Cell Biol 143: 1947–1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowder MA, Appelbaum JS, Hobert EM, Schepartz A (2011) Visualizing protein partnerships in living cells and organisms. Curr Opin Chem Biol 15: 781–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meitinger F, Boehm ME, Hofmann A, Hub B, Zentgraf H, Lehmann WD, Pereira G (2011) Phosphorylation-dependent regulation of the F-BAR protein Hof1 during cytokinesis. Genes Dev 25: 875–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JP, Lo RS, Ben-Hur A, Desmarais C, Stagljar I, Noble WS, Fields S (2005) Large-scale identification of yeast integral membrane protein interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 12123–12128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RK, Cheng SC, Rose MD (2000) Bim1p/Yeb1p mediates the Kar9p-dependent cortical attachment of cytoplasmic microtubules. Mol Biol Cell 11: 2949–2959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen EM, McDonald H, Yates J 3rd, Kellogg DR (2002) Cell cycle-dependent assembly of a Gin4-septin complex. Mol Biol Cell 13: 2091–2105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motulsky HJ, Ransnas LA (1987) Fitting curves to data using nonlinear regression: a practical and nonmathematical review. FASEB J 1: 365–374 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J, Johnsson N (2008) Split-ubiquitin and the split-protein sensors: chessman for the endgame. Chembiochem 9: 2029–2038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkuni K, Okuda A, Kikuchi A (2003) Yeast Nap1-binding protein Nbp2p is required for mitotic growth at high temperatures and for cell wall integrity. Genetics 165: 517–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuzaki D, Nojima H (2001) Kcc4 associates with septin proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett 489: 197–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philips J, Herskowitz I (1998) Identification of Kel1p, a kelch domain-containing protein involved in cell fusion and morphology in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 143: 375–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt MR, Schwartz EC, Muir TW (2007) Small-molecule-mediated rescue of protein function by an inducible proteolytic shunt. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 11209–11214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Przytycka TM, Singh M, Slonim DK (2010) Toward the dynamic interactome: it's about time. Brief Bioinform 11: 15–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabut G, Doye V, Ellenberg J (2004) Mapping the dynamic organization of the nuclear pore complex inside single living cells. Nat Cell Biol 6: 1114–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu YJ, Santos B, Fortin N, Costigan C, Snyder M (1998) Spa2p interacts with cell polarity proteins and signaling components involved in yeast cell morphogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 18: 4053–4069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slaughter BD, Unruh JR, Li R (2011) Fluorescence fluctuation spectroscopy and imaging methods for examination of dynamic protein interactions in yeast. Methods Mol Biol 759: 283–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight AF, Shou W, Dowd GJ, Turck CW, Deshaies RJ, Johnson AD, Moazed D (1999) Net1, a Sir2-associated nucleolar protein required for rDNA silencing and nucleolar integrity. Cell 97: 245–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stynen B, Tournu H, Tavernier J, Van Dijck P (2012) Diversity in genetic in vivo methods for protein-protein interaction studies: from the yeast two-hybrid system to the mammalian split-luciferase system. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76: 331–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarassov K, Messier V, Landry CR, Radinovic S, Serna Molina MM, Shames I, Malitskaya Y, Vogel J, Bussey H, Michnick SW (2008) An in vivo map of the yeast protein interactome. Science 320: 1465–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uetz P, Giot L, Cagney G, Mansfield TA, Judson RS, Knight JR, Lockshon D, Narayan V, Srinivasan M, Pochart P, Qureshi-Emili A, Li Y, Godwin B, Conover D, Kalbfleisch T, Vijayadamodar G, Yang M, Johnston M, Fields S, Rothberg JM (2000) A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 403: 623–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui T, Maekawa H, Pereira G, Schiebel E (2003) The XMAP215 homologue Stu2 at yeast spindle pole bodies regulates microtubule dynamics and anchorage. EMBO J 22: 4779–4793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal M, Cusick ME, Barabasi AL (2011) Interactome networks and human disease. Cell 144: 986–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin R, Hwang ES, Amon A (1999) Cfi1 prevents premature exit from mitosis by anchoring Cdc14 phosphatase in the nucleolus. Nature 398: 818–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winey M, Bloom K (2012) Mitotic spindle form and function. Genetics 190: 1197–1224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittke S, Lewke N, Müller S, Johnsson N (1999) Probing the molecular environment of membrane proteins in vivo. Mol Biol Cell 10: 2519–2530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Braun P, Yildirim MA, Lemmens I, Venkatesan K, Sahalie J, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Gebreab F, Li N, Simonis N et al. (2008) High-quality binary protein interaction map of the yeast interactome network. Science 322: 104–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.