Abstract

Small GTP-binding proteins of the Arf family (Arf GTPases) interact with multiple cellular partners and with membranes to regulate intracellular traffic and organelle structure. Understanding the underlying molecular mechanisms requires in vitro biochemical assays to test for regulations and functions. Such assays should use proteins in their cellular form, which carry a myristoyl lipid attached in N-terminus. N-myristoylation of recombinant Arf GTPases can be achieved by co-expression in E. coli with a eukaryotic N-myristoyl transferase. However, purifying myristoylated Arf GTPases is difficult and has a poor overall yield. Here we show that human Arf6 can be N-myristoylated in vitro by recombinant N-myristoyl transferases from different eukaryotic species. The catalytic efficiency depended strongly on the guanine nucleotide state and was highest for Arf6-GTP. Large-scale production of highly pure N-myristoylated Arf6 could be achieved, which was fully functional for liposome-binding and EFA6-stimulated nucleotide exchange assays. This establishes in vitro myristoylation as a novel and simple method that could be used to produce other myristoylated Arf and Arf-like GTPases for biochemical assays.

Keywords: small GTPases, Arf, Arf-like, myristoylation

Introduction

Small GTP-binding proteins (called small GTPases hereafter) of the Arf and Arf-like family regulate various functions in cells, many of which are associated with membrane traffic (reviewed in ref. 1 and 2). The distinctive feature of this family is that its members couple their activation by GDP/GTP exchange to their recruitment to membranes by using a unique GDP/GTP structural switch.3 Thereby, the guanine nucleotide-binding site communicates with a N-terminal amphipathic helix located on the opposite side of the small GTPase, which secures the GTP-bound form to membranes as best described for Arf family members.4-6 In various members of the family, including Arf proteins,7-9 Arl1,10 Arl611 and Arl4D,12 interaction of the N-terminal helix with membranes is reinforced by a 14-carbon myristoyl fatty acid attached to the N-terminal glycine (Fig. 1). While the myristoyl group provides only a weak and reversible attachment to membranes, its combination with the GDP/GTP structural switch results in strong membrane attachment, which is needed for efficient activation and subsequent interactions of these small GTPases with downstream effectors. Therefore, biomimetic assays that reconstitute Arf or Arf-like processes, whether they involve activation by their guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), termination by their GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) or recruitment of effectors must be set up with their myristoylated form.

Figure 1. Model of attachment of myr-Arf6•GTP to membranes. The myristoylated N-terminal amphipatic helix of Arf6 interacts with membranes, and communicates with the nucleotide-binding site by the interswitch and switch regions (shown in black). GTP is shown in ball-and-stick. Drawn from PDB entry 2J5X.

N-myristoylation is catalyzed by myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferases (NMTs), which are well conserved enzymes in higher eukaroytes (reviewed in ref. 13). It occurs mostly co-translationally after the initial methionine has been cleaved, although a few cases of post-translational N-myristoylation have also been reported.14 High yield production of myristoylated proteins (in the milligram range) is currently based on co-expression in bacteria of an eukaryotic NMT and the protein of interest, a method first described for a mammalian protein kinase subunit.15 Variations in the method make use of either two plasmids carrying the NMT and its substrate protein genes, as exemplified by studies on Arf GTPases,8,16 or of a single biscistronic plasmid carrying both genes, a method that has not been used to N-myristoylate mammalian proteins.17 In the case of Arf proteins, poor myristoylation rates, a tendency for plasmid loss and a complex purification scheme add up to limit the overall yield to at best 0.5 mg per liter of culture (our unpublished results). Alternatively, in vitro myristoylation using a recombinant NMT has been reported for a full-length Rab small GTPase from plants,18 but this method has not been applied for high yield production.

Here, we use purified recombinant NMTs and Arf6 to produce N-myristoylated Arf6, an Arf isoform that couples membrane traffic at the plasma membrane to actin cytoskeleton reorganization and has been associated to cancer cell migration (reviewed in ref. 19). We show that this method allows high yield production of myristoylated Arf6, and that the protein is fully functional for liposome-binding and GEF-stimulated nucleotide exchange assays.

Results and Discussion

Efficiency of in vitro myristoylation of Arf6 by recombinant NMTs

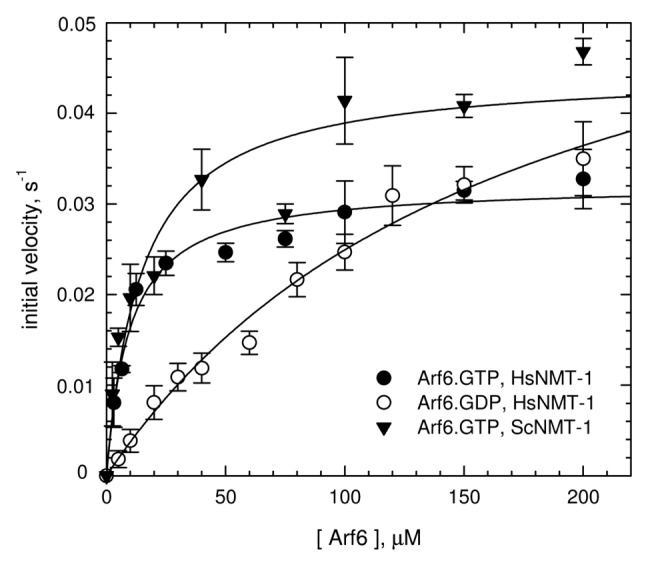

N-myristoylation of Arf6 is essential for its recruitment to subcellular membranes and effect on endocytotic transport.9 NMR studies of the myristoylated Arf6 N-terminal peptide (myr-GKVLSKIFNGKE) showed that it binds to micelles by the combined interaction of hydrophobic residues with the micelle surface and insertion of the myristoyl group into the lipid monolayer.20 In order to reconstitute N-myristoylation of Arf6 in vitro, we first expressed full-length recombinant human Arf6 in E. coli and purified it to homogeneity. The protein was essentially bound to GTP as estimated by tryptophan fluorescence.31 Depending on the protein preparation, cleavage of the initiator methionine was found to be between 88% and 100%, as measured by Edman degradation or mass spectrometry (see Fig. 3A), thus making it a good potential target for in vitro N-myristoylation. We then compared the efficiency of recombinant from E.coli NMTs from plant, yeast and human at fixed NMT (0.5 μM) and Arf6•GTP (400 μM) concentrations using a coupled N-myristoylation kinetics assay,18 in which detection by absorbance was replaced by fluorescence detection.21 Arf6•GTP was efficiently modified by NMTs from all species, with rate constants of 0.011 ± 0.002 sec−1, 0.044 ± 0.005 sec−1 and 0.031 ± 0.002 sec−1 for AtNMT1, ScNMT1 and HsNMT1 respectively, which were only slightly lower than that obtained for the calcium sensor AtSOS3 N-terminal peptide (GCSVSKKK, 0,179 ± 0.002 sec−1) used as a reference peptide.18 Detailed kinetics analysis was performed for ScNMT1 and HsNMT1, the two most active NMTs, over a range of Arf6•GTP concentrations, confirming that both enzymes have similar KM, kcat and kcat/KM (Table 1; Fig. 2). Next, we analyzed whether N-myristoylation of Arf6 is sensitive to the nature of the bound nucleotide. N-myristoylation efficiency (kcat/KM) of HsNMT1 for Arf6•GDP was reduced by a factor of ~8.5 compared with Arf6•GTP, mostly due to ~18-fold decrease in affinity (Table 1; Fig. 2). This likely reflects the fact that the N-terminal helix is more readily accessible in Arf6•GTP22 than in Arf6•GDP.23 We conclude that recombinant Arf6 can be efficiently myristoylated in vitro by recombinant eukaryotic NMTs, with about the same efficiency regardless of the NMT species, but with a marked preference of NMT for the GTP-bound conformation over the GDP-bound conformation.

Figure 3. In vitro production of myristoylated Arf6•GTP. (A) Nano ESI-MS analysis of Arf6 before (left) and after (right) in vitro myristoylation and ammonium sulfate fractionation. The molecular mass difference is 221 Da, accounting for the addition of a myristoyl group of 221 Da. Note that the unmyristoylated Arf6 sample used here has 100% of its N-terminal methionine cleaved, and that unmyristoylated Arf6 is not detected in the myr-Arf6 sample. (B) Migration on a 15% SDS polyacrylamide gel of purified recombinant Arf6 (2 μg) before (1) and after (2) in vitro myristoylation and ammonium sulfate precipitation. Note that myr-Arf6 migrates at a slightly lower apparent mass than unprocessed Arf6. The left and right lanes contain the molecular mass markers of the indicated sizes. Proteins are stained with Coomassie blue.

Table 1. - Kinetic parameters of in vitro Arf6 N-myristoylation.

| Enzyme | Substrate | kcat, s−1 | KM, μM | kcat/KM, M−1s−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ScNMT1 |

Arf6-GTP |

0.045 ± 0.003 |

14.6 ± 4.3 |

3082 |

|

HsNMT1 |

Arf6-GDP |

0.068 ± 0.008 |

172 ± 33 |

395 |

| Arf6-GTP | 0.032 ± 0.001 | 9.7 ± 1.6 | 3299 |

All values were obtained from a Michaelis-Menten fit of a plot containing three independent experiments (± S.D.).

Figure 2. Kinetics analysis of N-myristoylation of Arf6 by eukaryotic NMTs. Michaelis-Menten analyses of the dependence of the initial velocity (s−1) as a function of Arf6 concentration. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. The kinetic parameters derived from these analyses are in Table 1.

High yield production of myristoylated Arf6•GTP

Based on these results, we scaled up the in vitro myristoylation protocol in order to produce milligram amounts of pure myristoylated Arf6. To minimize denaturation over time due to temperature or to the detergent needed to dissolve myristoyl-CoA, experiments were done at room temperature rather than 37°C and the concentration of myristoyl-CoA was set to 1.4 molar excess over the Arf6 GTPase concentration. The concentration of Arf6•GTP was set to 10 × KM (100 μM), that of HsNMT to catalytic amounts (0.5–1.2 μM). After 4–5 h incubation the reaction mixture was subjected to 35% ammonium sulfate precipitation to separate myristoylated Arf6•GTP from unprocessed Arf6•GTP. Nano Electro Spray Ionisation-Mass Spectrometry (ESI-MS) analysis of Arf6 before and after N-myristoylation and ammonium sulfate precipitation identified single components with molecular masses of 20014 Da and 21225 Da, respectively (Fig. 3A). The Δm of 211 ± 2 Da is similar to the monoisotopic and average delta masses expected for N-terminal myristoylation (210.1984 and 210.3598 Da, respectively).24Figure 3B shows that Arf6 recovered in the pellet appears as a single band slightly down-shifted on SDS-PAGE as compared with non-myristoylated Arf6•GTP, as previously observed for myr-Arf6 produced by co-expression in E. coli.8 SDS-PAGE and ESI-MS analysis thus indicate that highly pure and fully myristoylated Arf6•GTP can be produced by in vitro myristoylation followed by ammonium sulfate precipitation. The final yield was about 50%, corresponding to up to 5–7 mg of purified myr-Arf6 per liter of culture.

In vitro myristoylated Arf6 is fully functional in biochemical assays

In order to assess that myr-Arf6 produced with this new procedure was fully functional, we first examined the liposome-binding properties of myr-Arf6•GDP and myr-Arf6•GTP by flotation experiments. We used liposomes that resemble the plasma membrane and early endosomes (reviewed in ref. 25), which is where Arf6 is mostly located in cells (reviewed in ref. 19). Figure 4A shows that myr-Arf6•GDP was mostly soluble and interacts only slightly with membranes, while myr-Arf6•GTP was almost entirely bound to the liposomes. These results indicate that myr-Arf6 produced by in vitro myristoylation interacts with membranes in a nucleotide-dependent manner, which is consistent with previous observations using myristoylated Arf6 produced in bacteria.26 Next we analyzed whether myr-Arf6•GDP, prepared from myr-Arf6-GTP by spontaneous GDP/GTP exchange, could be activated by an Arf6-specific exchange factor, EFA6 (Exchange Factor for Arf6).27 Nucleotide exchange experiments were performed in the presence of the same liposomes as above, and monitored by tryptophan fluorescence kinetics. As shown in Figure 4B, nucleotide exchange of myr-Arf6•GDP (0.4 μM) was stimulated by ~64-fold in the presence of catalytic amounts (10 nM) of EFA6 (kobs ~0.0014 ± 0.0005 sec−1 and 0.089 ± 0.004 sec−1, respectively). Altogether, these experiments show that both GDP-bound and GTP-bound myristoylated Arf6 can be produced in large quantities by in vitro N-myristoylation, and that both are fully functional and can be used in biomimetics assay.

Figure 4. In vitro myristoylated Arf6 is fully functional. (A) Interaction of myr-Arf6 (2 μM) with liposomes [1 mM, containing 34.3%PC, 14%PS, 21% PS, 0.7% PtdIns(4,5)P2 and 30% cholesterol] assessed by a flotation assay. Unbound Arf6 is recovered in the bottom fraction, liposome-bound Arf6 in the top fraction. 100% corresponds to the intensity of the input normalized to the volume for each fraction. Myr-Arf6•GDP is mostly soluble and myr-Arf6•GTP is fully bound to membranes, as previously observed for myr-Arf6 produced by co-expression with NMT in E. coli. (B) EFA6-stimulated nucleotide exchange of myr-Arf6•GDP. Representative tryptophan fluorescence kinetics traces of GDP/GTP exchange of myr-Arf6•GDP (0.4 μM) in the absence or presence of 10 nM EFA6 (as indicated) and in the presence of 100 μM liposomes. Nucleotide exchange was triggered by the addition of 100 μM GTP, at 37°C. The kinetic traces were fit to a single exponential function and yielded the kobs reported in the text.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals

Soya phosphatidylcholine (PC), liver phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), brain phosphatidylserine (PS), ovine wool cholesterol and brain phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate were from Avanti Polar Lipids, NBD-PE was from Invitrogen. All other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich. Stock solutions of myristoyl-CoA (0.2–0.4 mM) were prepared in sodium acetate, pH 5.6, 1% Triton X-100.

Expression and purification of recombinant NMTs, human Arf6 and human EFA6

Recombinant NMTs from Arabidopsis thaliana (isoform 1, AtNMT1), Saccharomyces cerevisiae (isoform 1, ScNMT1) and Homo sapiens (isoform 1, HsNMT1) carrying a 6-His tag in N-terminus were overexpressed in E. coli and purified as previously described.18,28 Purified NMTs (> 90% pure as estimated by SDS-PAGE) were dialyzed against 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.3, 0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 55% glycerol and were stored at -20°C prior to being used.

The plasmid for human Arf6 carrying a C-terminal 6 × His Tag (pET21b vector) is a kind gift from Michel Franco (IPMC, CNRS). Arf6 was overexpressed in BL21(DE3) pLysS Escherichia coli strain in the presence of ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and chloramphenicol (34 μg/mL). Cells were grown for 4–6 h after induction with 0.5 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG) at 27°C, then resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (NaPi), pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10 mM imidazole) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktails, and incubated with lysozyme (1 mg/mL) for 1 h at 4°C under stirring, then for another 30 min with 5 μL/L benzonase, 5 mM MgCl2 and 0.05% deoxycholate (w/v). The cell lysate was then centrifuged for 60 min at 18,000 rpm then for 60 min at 40,000 rpm, and diluted to a final concentration of 3–5 mg/mL before loading onto a 5 mL His-Trap nickel affinity column (GE Healthcare). After washing with 20–30 column volumes of lysis buffer supplemented with 40 mM imidazole, the protein was eluted with a 40–250 mM gradient of imidazole in lysis buffer. Fractions containing Arf6 were pooled, concentrated and dialyzed against 50 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM MgCl2 (buffer A) and loaded onto a 1 mL MonoQ ion exchange column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer A. Purified Arf6 (> 95% pure as estimated by SDS-PAGE) was recovered in the flow-through fraction. The protein was then concentrated to ~2.5 mM on a Vivaspin centricon (10 kDa cut-off membrane), flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until further use. The final yield of purified Arf6 is up to 15 mg per liter of culture.

Sequence encoding EFA6a was amplified from the IMAGE cDNA clone 40148656. The C-terminal half of EFA6a, encompassing the catalytic Sec7 domain and the membrane-binding PH domain (residues 527–1024, called EFA6 hereafter), was subcloned into the pProEXHtb vector. EFA6 carrying a 6-histidine tag was overexpressed in BL21(DE3) pLysS. Cells were grown at 37°C in LB medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 34 μg/mL chloramphenicol to an A600nm of 0.6–0.8, then induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 4 h at 30°C. Cells were resuspended in ~50 mL of lysis buffer (50 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM imidazole) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail. The cell lysate, obtained as described for Arf6, was loaded onto a 3–5 mL nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-Sepharose (Ni-NTA) column (Qiagen). After washing with 20 column volumes of lysis buffer supplemented with 40 mM imidazole, the protein was eluted with 250 mM imidazole in lysis buffer. Fractions containing EFA6 were pooled, concentrated and loaded onto a PD-10 column equilibrated with 20 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl to remove imidazole. The protein solution was loaded onto a 0.8 mL miniQ ion exchange column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl. The column was then washed with 12 mL of the same buffer and eluted with a 10 mL gradient from 150 mM to 1 M NaCl in 20 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 8.0. Fractions containing purified EFA6 (> 90% pure as estimated by SDS-PAGE) were pooled, concentrated, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until further use.

N-myristoylation kinetics assays

The kinetics of N-myristoylation catalyzed by NMTs was monitored by a modification of the coupled assay described in18 in which absorbance detection of NADH production was replaced by fluorescence detection (λexc = 340 nm, λem = 475 nm).21 All experiments were done at 30°C in 96-well black microplates in a final volume of 100 μL containing Arf6, 0.5 μM NMT and 0.125 units/mL of porcine heart pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) in 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EGTA, 0.3 mM DTT, 0.2 mM thiamine pyrophosphate, 2 mM pyruvate, 0.1 mg/mL bovine serum albumine, 40 μM myristoyl-coenzyme A (myr-CoA), 0.1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM NAD+. The range of Arf6 concentrations for the determination of the kinetic parameters was 2.5–200 μM, or was set to 400 μM for the preliminary kinetics experiments. Kinetics parameters were derived as described in.18

Production and purification of myristoylated Arf6

Arf6•GTP (100 μM) was incubated with 140 μM myr-CoA and 0.5–1.2 μM HsNMT-1 in 5–10mL final volume for 4–5 h at room temperature. Myristoylated Arf6 was separated from unprocessed Arf6 by precipitation in 35% ammonium sulfate at 4°C. Myr-Arf6 was recovered in the pellet after centrifugation (18,000 rpm, 4°C), resuspended in HKM buffer (50 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, 120 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM MgCl2) containing 2 mM β-mercaptoethanol and dialyzed overnight against the same buffer.

Liposome flotation assay

All liposomes contained 34.3% PC, 14% PE, 21% PS, 0.7% PIP2, 30% cholesterol and 0.2% NBD-PE. Liposomes were prepared as described29 except that they were resuspended in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 120 mM potassium acetate buffer at 2 mM. Unilamellar liposomes were prepared freshly before the binding or exchange assays by extrusion of ~300–600 μL of the lipids suspension stock through a polycarbonate filter (pore size = 0.2 μm). Binding of myr-Arf6•GDP or myr-Arf6•GTP to liposomes was assessed by flotation as described.30 Protein samples (2 μM) were incubated for 5 min at room temperature with 1 mM liposomes in HKM buffer supplemented with 1 mM DTT, and treated as previously reported.30 The suspension was adjusted to 30% sucrose, overlaid with a HKM cushion containing 25% sucrose then another one containing no sucrose. After ultracentrifugation at 55,000 rpm for 1h in a TLS-55 rotor (Beckman Coulter), fractions of soluble and liposome-bound protein (bottom and top respectively) were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE after sypro-orange staining (Molecular Probes). Integrity and recovery of the liposomes was followed through fluorescence of NBD-PE. Gels were visualized with a FUJI LAS-3000 imaging system and quantified using the ImageJ64 software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Nucleotide exchange assays

The nucleotide content of purified recombinant Arf6 was assessed by monitoring the change in tryptophan fluorescence (λexc = 298nm, λem = 340 nm) following addition of GDP or GTP in the presence of EDTA (5mM), which takes advantage of the large difference in fluorescence between the GDP- and GTP-bound forms of Arf proteins.31 No fluorescence change was observed upon addition of 100 μM GTP, whereas there was a large fluorescence decrease upon addition of 100 μM GDP, indicating that bacterially-expressed Arf6 is mostly GTP-bound. Arf6•GDP was obtained by incubating Arf6•GTP (0.1–0.5 mM) in the presence of 5 mM GDP in 50 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 8.0, 5mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT for 40 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped by addition of 20 mM MgCl2, then excess nucleotides were removed on a PD-10 column pre-equilibrated in 50 mM TRIS-HCl, pH 8, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM MgCl2. The same protocol, but performed in HKM buffer, was used to produce myr-Arf6•GDP from myr-Arf6•GTP.

GEF-stimulated nucleotide exchange kinetics were monitored by tryptophan fluorescence essentially as described in.32 Experiments were performed at 37°C in HKM buffer supplemented with 1mM DTT with 0.4 μM myr-Arf6•GDP, 100 μM liposomes, 10 nM EFA6 and were started by the addition of 100 μM GTP. Spontaneous nucleotide exchange was monitored with the same assay. The exchange rates (kobs, s−1) were determined by fitting the data to a mono-exponential function.

Conclusion

In this work we describe a novel method to produce large amounts of pure myristoylated Arf6. It takes advantage of the fact that non-myristoylated Arf proteins can be expressed and purified in large quantities, using simple expression and purification schemes. Likewise, His-tagged NMTs from various eukaryotes are readily expressed and purified using single-step affinity chromatography. Notably, all chromatography steps are performed on the unprocessed small GTPase rather than on its myristoylated form, thus avoiding important protein loss associated with the presence of the myristoyl group. We expect that the method can readily be implemented to myristoylate other small GTPases of the Arf and Arf-like family from their purified unprocessed form.3 This should be valuable for the biomimetic reconstitution of membrane trafficking pathways involving these small GTPases, their regulators and their effectors. More generally, the method should apply to other myristoylable protein substrate, provided a simple method such as ammonium sulfate precipitation is available for separating the myristoylated protein from its non-myristoylated precursor.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC) to D.P., a grant from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) to J.C. and fellowships from the ANR and from CNRS to J.A.T. We are grateful to Laetitia Cormier (LEBS/IMAGIF cloning platform, CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette) for cloning of the EFA6 plasmid, to Manuella Argentini and David Cornu (IMAGIF/IFR115, mass spectrometry platform, CNRS, Gif-sur-Yvette) for mass spectrometry analysis, and to Régine Lebrun (Plate-forme Protéomique de l'Institut de Microbiologie de la Méditerranée) for Edman sequencing.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/smallgtpases/article/22895

References

- 1.D’Souza-Schorey C, Chavrier P. ARF proteins: roles in membrane traffic and beyond. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:347–58. doi: 10.1038/nrm1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahn RA, Cherfils J, Elias M, Lovering RC, Munro S, Schurmann A. Nomenclature for the human Arf family of GTP-binding proteins: ARF, ARL, and SAR proteins. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:645–50. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasqualato S, Renault L, Cherfils J. Arf, Arl, Arp and Sar proteins: a family of GTP-binding proteins with a structural device for ‘front-back’ communication. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:1035–41. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amor JC, Harrison DH, Kahn RA, Ringe D. Structure of the human ADP-ribosylation factor 1 complexed with GDP. Nature. 1994;372:704–8. doi: 10.1038/372704a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antonny B, Beraud-Dufour S, Chardin P, Chabre M. N-terminal hydrophobic residues of the G-protein ADP-ribosylation factor-1 insert into membrane phospholipids upon GDP to GTP exchange. Biochemistry. 1997;36:4675–84. doi: 10.1021/bi962252b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Renault L, Guibert B, Cherfils J. Structural snapshots of the mechanism and inhibition of a guanine nucleotide exchange factor. Nature. 2003;426:525–30. doi: 10.1038/nature02197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kahn RA, Goddard C, Newkirk M. Chemical and immunological characterization of the 21-kDa ADP-ribosylation factor of adenylate cyclase. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:8282–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franco M, Chardin P, Chabre M, Paris S. Myristoylation-facilitated binding of the G protein ARF1GDP to membrane phospholipids is required for its activation by a soluble nucleotide exchange factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1573–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.D’Souza-Schorey C, Stahl PD. Myristoylation is required for the intracellular localization and endocytic function of ARF6. Exp Cell Res. 1995;221:153–9. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu L, Horstmann H, Ng C, Hong W. Regulation of Golgi structure and function by ARF-like protein 1 (Arl1) J Cell Sci. 2001;114:4543–55. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price HP, Hodgkinson MR, Wright MH, Tate EW, Smith BA, Carrington M, et al. A role for the vesicle-associated tubulin binding protein ARL6 (BBS3) in flagellum extension in Trypanosoma brucei. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1178–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li CC, Chiang TC, Wu TS, Pacheco-Rodriguez G, Moss J, Lee FJ. ARL4D recruits cytohesin-2/ARNO to modulate actin remodeling. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4420–37. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farazi TA, Waksman G, Gordon JI. The biology and enzymology of protein N-myristoylation. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39501–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100042200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zha J, Weiler S, Oh KJ, Wei MC, Korsmeyer SJ. Posttranslational N-myristoylation of BID as a molecular switch for targeting mitochondria and apoptosis. Science. 2000;290:1761–5. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duronio RJ, Jackson-Machelski E, Heuckeroth RO, Olins PO, Devine CS, Yonemoto W, et al. Protein N-myristoylation in Escherichia coli: reconstitution of a eukaryotic protein modification in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1506–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ha VL, Thomas GM, Stauffer S, Randazzo PA. Preparation of myristoylated Arf1 and Arf6. Methods Enzymol. 2005;404:164–74. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)04016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glück JM, Hoffmann S, Koenig BW, Willbold D. Single vector system for efficient N-myristoylation of recombinant proteins in E. coli. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e10081. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boisson B, Meinnel T. A continuous assay of myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase for proteomic analysis. Anal Biochem. 2003;322:116–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schweitzer JK, Sedgwick AE, D’Souza-Schorey C. ARF6-mediated endocytic recycling impacts cell movement, cell division and lipid homeostasis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gizachew D, Oswald R. NMR structural studies of the myristoylated N-terminus of ADP ribosylation factor 6 (Arf6) FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Traverso J, Giglione C, Meinnel T. High-throughput profiling of N-myristoylation substrate specificity across species including pathogens. Proteomics. 2012 doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200375. in the press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pasqualato S, Ménétrey J, Franco M, Cherfils J. The structural GDP/GTP cycle of human Arf6. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:234–8. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ménétrey J, Macia E, Pasqualato S, Franco M, Cherfils J. Structure of Arf6-GDP suggests a basis for guanine nucleotide exchange factors specificity. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:466–9. doi: 10.1038/75863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilkins MR, Gasteiger E, Gooley AA, Herbert BR, Molloy MP, Binz PA, et al. High-throughput mass spectrometric discovery of protein post-translational modifications. J Mol Biol. 1999;289:645–57. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:112–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Macia E, Luton F, Partisani M, Cherfils J, Chardin P, Franco M. The GDP-bound form of Arf6 is located at the plasma membrane. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2389–98. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franco M, Peters PJ, Boretto J, van Donselaar E, Neri A, D’Souza-Schorey C, et al. EFA6, a sec7 domain-containing exchange factor for ARF6, coordinates membrane recycling and actin cytoskeleton organization. EMBO J. 1999;18:1480–91. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierre M, Traverso JA, Boisson B, Domenichini S, Bouchez D, Giglione C, et al. N-myristoylation regulates the SnRK1 pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2804–21. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.051870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stalder D, Barelli H, Gautier R, Macia E, Jackson CL, Antonny B. Kinetic studies of the Arf activator Arno on model membranes in the presence of Arf effectors suggest control by a positive feedback loop. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:3873–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.145532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bigay J, Antonny B. Real-time assays for the assembly-disassembly cycle of COP coats on liposomes of defined size. Methods Enzymol. 2005;404:95–107. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)04010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zeeh JC, Antonny B, Cherfils J, Zeghouf M. In vitro assays to characterize inhibitors of the activation of small G proteins by their guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Methods Enzymol. 2008;438:41–56. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)38004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeeh JC, Zeghouf M, Grauffel C, Guibert B, Martin E, Dejaegere A, et al. Dual specificity of the interfacial inhibitor brefeldin a for arf proteins and sec7 domains. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11805–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]