Abstract

Active matrix flat-panel imagers (AMFPIs) offer many advantages and have become ubiquitous across a wide variety of medical x-ray imaging applications. However, for mammography, the imaging performance of conventional AMFPIs incorporating CsI:Tl scintillators or a-Se photoconductors is limited by their relatively modest signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), particularly at low x-ray exposures or high spatial resolution. One strategy for overcoming this limitation involves the use of a high gain photoconductor such as mercuric iodide (HgI2) which has the potential to improve the signal-to-noise ratio by virtue of its low effective work function (WEFF). In this study, the performance of direct-detection AMFPI prototypes employing relatively thin layers of polycrystalline HgI2 operated under mammographic irradiation conditions over a range of 0.5 to 16.0 mR is presented. High x-ray sensitivity (corresponding to WEFF values of ~19 eV), low dark current (<0.1 pA/mm2) and good spatial resolution, largely limited by the size of the pixel pitch, were observed. For one prototype, a detective quantum efficiency of ~70% was observed at an x-ray exposure of ~0.5 mR at 26 kVp.

Keywords: Active matrix flat panel imager, polycrystalline HgI2, DQE, screen-printing

1. Introduction

Since the clinical introduction in the late 1990s of active matrix flat panel imagers (AMFPIs) based on two-dimensional pixelated arrays, this solid-state x-ray imaging technology has become widely adopted for many applications, including radiography, fluoroscopy, radiotherapy and mammography. The nearly ubiquitous presence of AMFPIs in medical environments is due to their many advantages which include real-time digital acquisition, high image quality, and compactness. However, for arrays with very small pixels, or under conditions of low exposure, or at high spatial frequencies, the performance of conventional AMFPIs is constrained as a result of a relatively modest ratio of imaging signal to electronic additive noise. (Antonuk et al., 2000) For example, in mammographic AMFPI systems, as the exposure decreases, the signal to noise ratio (SNR) of such systems declines, leading to a significant reduction in detective quantum efficiency (DQE). This is illustrated in Fig. 1 where cascaded systems analysis calculations of DQE for conventional AMFPIs employing direct and indirect detection of the incident radiation by means of photoconductive and scintillating x-ray converters based on a-Se and CsI:Tl, respectively, are plotted as a function of exposure. These calculations are based on cascaded systems models similar to those used in previous studies. (Du et al., 2008; El-Mohri et al., 2007) The calculations illustrate that, compared to zero-frequency DQE values at high exposures (e.g., above ~2 mR) which approach an upper limit given by the product of the x-ray detection efficiency and the Swank factor of a given converter, the zero-frequency DQE of mammographic AMFPI systems drops more than 44% at low exposures (e.g., less than ~0.2 mR). Such DQE loss is even more pronounced at higher (i.e., non-zero) spatial frequencies. (El-Mohri et al., 2007)

Figure 1.

Cascaded systems calculations of zero-frequency DQE plotted as a function of exposure for a variety of hypothetical direct and indirect detection active matrix flat-panel imager designs. These calculations assume a pixel pitch of 100 μm, a signal collection fill factor of 100% and an electronic additive noise level of 3000 e [rms]. The calculations further assume a 26 kVp x-ray spectrum with a Mo/Mo target/filter combination and use of a 5 cm BR-12 phantom. The dashed lines correspond to the performance of “conventional” AMFPI designs employing the type of direct and indirect detection x-ray converters commonly used for mammographic AMFPIs. These calculations assume a-Se and CsI:Tl converter thicknesses of 200 and 150 μm, densities of 4.3 and 4.51 g/cm3, and effective work functions (WEFF) of 64 and 35 eV, respectively. In addition, calculations for AMFPI designs incorporating 100 μm thick HgI2 converters with a density of 6.36 g/cm3 (corresponding to the single crystal form of the material) and WEFF values of 5 and 20 eV, corresponding to the solid and dotted lines, respectively, are also shown.

Given that prospects for significant reduction in electronic additive noise are poor, (Antonuk et al., 2000) the most effective way to improve the SNR is through enhancement of the amount of signal extracted from each pixel per interacting X ray. One approach for accomplishing this goal is through replacement of the type of x-ray converters currently used in conventional mammographic AMFPIs (i.e., a-Se and CsI:Tl) with a converter offering significantly higher detected signal per interacting X ray – corresponding to a low effective work function, WEFF. (WEFF represents the average amount of deposited x-ray energy required to generate one detected electron-hole pair.) In response, a number of candidate photoconductive materials, including PbI2, PbO and HgI2 have been examined. (Street et al., 2002; Zuck et al., 2003; Hartsough et al., 2004; Kang et al., 2005; Simon et al., 2005; Su et al., 2005; Zentai et al., 2007; Du et al., 2008)

Perhaps the most examined of these materials are polycrystalline forms of mercuric iodide which have demonstrated relatively low values of WEFF – in some cases approaching that exhibited by the single-crystal form of the material, ~5 eV. (Street et al., 2002; Su et al., 2005) In addition, polycrystalline HgI2 offers a high average attenuation due to its large effective atomic number. Consequently, high detection efficiencies at mammographic energies can be achieved with layers of the material that are, for a given detector efficiency, thinner than those used for a-Se and CsI:Tl. Furthermore, polycrystalline HgI2 requires an electric field strength of only ~1 V/μm to achieve efficient charge collection, compared to the much higher strengths of ~10 V/μm required for a-Se. In the context of mammographic imaging, another advantage of HgI2 is that the lowest K-edge energy of the material is 33 keV, which lies above typical mammographic x-ray energies. As a result, there is typically no loss of spatial resolution nor increase in Swank noise from K-fluorescence reabsorption. By comparison, a-Se, which has a K-edge energy of 12.66 keV, suffers from a ~12% reduction in the modulation transfer function (MTF) at 5 lp/mm for a 200 μm thick a-Se converter using 28 kVp X rays. (Zhao et al., 2003) (In the case of CsI:Tl, the lowest K-edge energy is identical to that of HgI2.) Therefore, compared with x-ray converters used in conventional mammographic AMFPIs, HgI2 offers a variety of advantages – most importantly, the potential to overcome SNR-related limitations on AMFPI performance for small pixels, at low exposures, and at high spatial frequencies. As seen in the DQE calculations in Fig. 1, the incorporation of HgI2 with WEFF values of 5 and 20 eV (representing a range of favorable values observed in various prototype studies) enhances the SNR of AMFPIs to the degree that performance exhibits only a modest decline with decreasing exposure – demonstrating the potential for significant performance improvement at mammographic energies compared to CsI:Tl and a-Se which exhibit WEFF values of ~35 and 64 eV, respectively. (Stone et al., 2002)

For polycrystalline HgI2, two low temperature deposition methods (involving physical vapor deposition [PVD] and particle-in-binder [PIB] techniques, (Schieber et al., 1999; Schieber et al., 2001) both of which are compatible with deposition on large area AMFPI arrays) have been explored. In previous studies, AMFPI prototypes employing ~210 to 635 μm of polycrystalline HgI2 material prepared using both the PVD and PIB methods have been examined under radiographic, fluoroscopic and radiotherapy imaging conditions. (Du et al., 2008; Zhao et al., 2010; Zentai et al., 2004) In addition, an early investigation of the performance of an AMFPI prototype coated with 240 μm of PVD HgI2 under mammographic imaging conditions demonstrated DQE values up to ~60%. (El-Mohri et al., 2003) However, the performance of prototype imagers incorporating PIB HgI2 has not been previously investigated for mammographic imaging. Unlike PVD, which requires a vacuum chamber and long deposition times, PIB offer the merits of faster processing time and consumption of considerably less material. In addition, its material composition makes it potentially less chemically reactive with metals in the array – creating the possibility for elimination of the barrier layer typically employed in such prototypes. In this paper, following a limited, preliminary study conducted by our group, (Jiang et al., 2012) an empirical investigation exploring the potential of HgI2 prototypes prepared via a method referred to as SP (based on screen-printing techniques similar to PIB) to improve the performance of current AMFPIs under mammographic imaging conditions is reported and the results are compared to theoretical expectations.

2. Materials and Methods

Two prototypes, each consisting of a direct detection AMFPI array coated with polycrystalline HgI2, were examined in the study. In each case, the array employed (MD88, dpiX, CA) is based on the same array model used in an earlier study (Du et al., 2008) – a 127 μm pixel pitch design, with a pixel format of 1024 × 1024 and a geometric fill factor of ~85%. The HgI2 coating on the arrays was deposited at Radiation Monitoring Devices using a low temperature deposition technique based on a SP method. This method employs grains of purified HgI2 crystals mixed with a polymer binder material, with a composition, by volume, of approximately one to one for the two materials. The polymer was chosen to have approximately the same electrical resistance as the HgI2 grains, so as to facilitate the flow of x-ray induced charge across the boundaries between the HgI2 grains and the polymer. This mixture is made into a slurry by adding solvent, then deposited onto the surface of an array using screen-printing techniques, and subsequently cured using a low temperature sintering process to evaporate the solvent.

In our previous studies, HgI2 prototypes fabricated with both PVD and PIB deposition methods incorporated a thin layer of barrier material deposited on the array surface prior to photoconductor deposition so as to prevent chemical reactions between the photoconductor and metals in the underlying structure of the array. Although such barrier layers offer the added advantage of reducing the dark current, they can impede charge collection, resulting in loss of x-ray sensitivity and spatial resolution. In the present study, no barrier layer was introduced – a configuration made possible by virtue of improved surface topology and the good isolation, provided by the top passivation layer of the array, of the photoconductor material deposited on the surface of the array from reactive metals (such as aluminum) in the structure of the array.

Two prototypes, referred to as 9B and 11B, coated with ~26 and 117 μm thick layers of SP HgI2, consisting of ~4 μm grain HgI2 material, that stop ~59% and 97% of the incident x-ray beam, respectively, were investigated. These layer thicknesses are single crystal equivalent values determined through low energy x-ray attenuation measurements. The prototypes were connected to a custom electronic acquisition system. (Huang et al., 1999) The x-ray measurements were performed with a GE Senographe DMR (GE Medical Systems) mammographic unit operated at 26 kVp with a Mo target and an inherent filtration of 30 μm of Mo. A standard 5 cm tissue-equivalent breast phantom (BR-12, Nuclear Associates) was positioned between the source and the imager, and the source-to-detector distance (SDD) was set to ~65 cm. (Note that, to facilitate comparisons with results obtained in earlier performance evaluations of indirect detection AMFPI prototypes, (Jee et al., 2003; El-Mohri et al., 2007) the beam energy, target filtration, SDD and tissue equivalent breast phantom chosen for the present study were the same as the ones used in those previous studies.) Exposure was measured under the phantom at the same SDD using a standard ion chamber and dosimeter (Inovision models 96035B and 35050A, respectively). Prototype performance, including measurements of dark current, x-ray sensitivity, non-uniformity, MTF and DQE, was investigated using techniques similar to those employed in a previous study. (Du et al., 2008) For all measurements, the results reported correspond to data acquired from within a contiguous block of pixels (up to 8874 and 11500 pixels for prototypes 9B and 11B, respectively) representing the best performing part of each prototype. In addition, the values reported for pixel dark signal and pixel x-ray signal (as well as results for dark current and x-ray sensitivity derived from these quantities) were obtained by averaging the data obtained from those pixel blocks. Finally, the contribution of dark signal has been subtracted for all reported results involving the use of X rays.

3. Results

3.1. Dark current and pixel response

Pixel dark signal was measured in the absence of radiation as a function of frame time, TF, and photoconductor bias voltage, VBIAS. The results were found to increase linearly with TF, as expected. From the slope of this dark signal data, the dark current (which, except at very short frame times, is dominated by photoconductor leakage current) was determined and the results are plotted as a function of VBIAS in Fig. 2(a). While prototype 9B exhibits a dark current of a few pA/mm2, the dark current of prototype 11B is much lower, less than 0.1 pA/mm2 – which is slightly lower than the best results obtained from previous PIB prototypes examined by our group. (Du et al., 2008)

Figure 2.

(a) Dark current, normalized to unit photoconductor area, plotted as a function of photoconductor bias voltage. (b) Pixel x-ray signal plotted as a function of bias voltage. The vertical dashed lines indicate the operating voltage values selected for the remaining performance measurements.

X-ray induced pixel signal was measured as a function of VBIAS and the results are shown in Fig. 2(b). The data for the two prototypes were acquired at an exposure of ~16 mR and exhibit very similar behaviors. While sensitivity to the incident radiation is seen to increase with increasing VBIAS, dark current from some areas outside the region of interest was unusually high, requiring the use of relatively modest bias voltages to prevent damage to the array. For that reason, the operating voltages employed for the remaining performance measurements (−6 V and −16 V for prototypes 9B and 11B, respectively) were chosen based on a desire to achieve as high an x-ray sensitivity as possible, while maintaining a relatively low level of dark noise.

3.2. X-ray sensitivity and WEFF

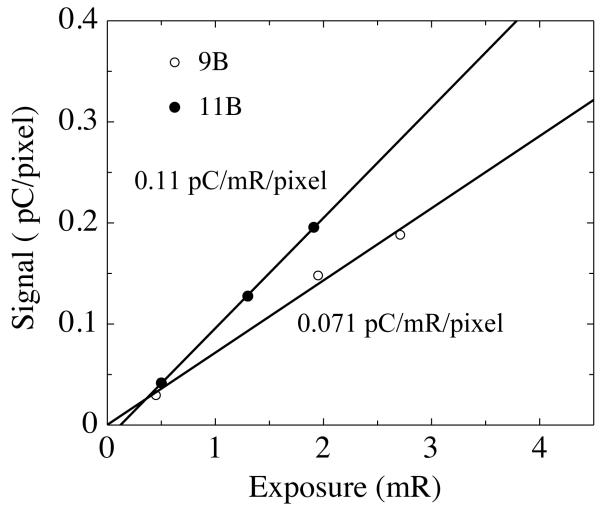

Measurements of pixel x-ray signal data plotted as a function of exposure are shown in Fig. 3. From the slope of the resulting linear relationships, x-ray sensitivity was determined to be 0.071 and 0.11 pC/mR/pixel for prototypes 9B and 11B, respectively. For the conditions under which these measurements were performed, the average energy absorbed in the photoconductor material was determined from Monte Carlo calculations using the EGS4 code (Jee et al., 2003) with an x-ray spectrum corresponding to the peak energy and beam filtration used in the prototype measurements. (El-Mohri et al., 2007) The resulting average x-ray energy absorbed per unit exposure divided by the corresponding measured sensitivity (expressed in electrons per unit exposure) yields WEFF values of ~19 and 20 eV for 9B and 11B, respectively. Although these WEFF values are higher than the best previously reported value for this material (~5 eV) (Street et al., 2002; Su et al., 2005), they are slightly lower than values ranging from 22 to 33 eV obtained from previous prototypes incorporating PIB material (Du et al., 2008) and, furthermore, are considerably lower than the values of ~35 eV and ~64 eV typical of the CsI:Tl and a-Se converters used in mammographic AMFPIs, respectively.

Figure 3.

Pixel x-ray signal plotted as a function of exposure. The lines correspond to fits to the data. The slopes of these lines, indicated in the figure, represent the x-ray sensitivity of each prototype.

3.3. Non-uniformity of pixel signal response

The pixel x-ray signal data used to determine x-ray sensitivity and WEFF were also used to examine non-uniformity in pixel x-ray signal response. Histograms of x-ray signal per pixel at three exposures for each of prototypes 9B and 11B appear in Figs. 4(a) and 4(b), respectively. For a given prototype and exposure, the non-uniformity in response is quantified through calculation of the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean of the distribution for the corresponding histogram – and the results are summarized in Table 1. As shown in Figs. 4(a) and 4(b), both prototypes exhibit considerable non-uniformity in response (11.5% to 18.0% for 9B, and 22.0% to 23.3% for 11B). The degree of non-uniformity is reduced after application of a gain correction (down to 3.1% to 6.8% for 9B, and 4.3% to 7.3% for 11B) as shown in Figs. 4(c) and 4(d), respectively. These gain-corrected empirical results are seen to be slightly greater than theoretical expectations based on the Gaussian distribution of pixel signal corresponding to that to be expected based solely on x-ray statistics – as shown in the figures and in Table 1. This may be due to anomalous temporal noise that increases the variation in the x-ray signal response from pixel to pixel. (Du et al., 2008) In addition, for both prototypes, the degree of non-uniformity is observed to exhibit some diminution with increasing exposure – consistent with the behavior predicted by x-ray statistics. Overall, the degree of non-uniformity observed from the present prototypes is comparable to that obtained from previous PIB prototypes. (Du et al., 2008)

Figure 4.

(a), (b) Histograms of pixel x-ray signal at various exposures for prototypes 9B and 11B. The results have been corrected only for dark signal. (c), (d) Histograms corresponding to the same data as in (a) and (b), after the application of a gain correction obtained from flood field measurements (Antonuk et al., 1992) which nominally accounts for pixel-to-pixel variation in x-ray signal response. For purposes of comparison, dashed curves representing the behavior to be expected based solely on x-ray statistics, obtained through Monte-Carlo calculation of radiation transport, are superimposed on (c) and (d).

Table 1.

The degree of non-uniformity in pixel x-ray signal response measured for prototypes 9B and 11B before and after application of a gain correction. For comparison, the corresponding non-uniformity values based solely on x-ray statistics are also given.

| 9B | 11B | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure (mR) | 0.45 | 1.95 | 2.71 | 0.51 | 1.3 | 1.9 |

| Before Correction | 18.0% | 11.8% | 11.5% | 23.3% | 22.5% | 22.0% |

| After Correction | 6.8% | 3.7% | 3.1% | 7.3% | 4.4% | 4.3% |

| X-ray Statistics | 5.4% | 2.6% | 2.2% | 5.1% | 3.2% | 2.6% |

3.4. MTF

Results for the measurement of MTF, obtained using the angled slit method, (Fujita et al., 1992) are shown in Fig. 5. The MTF result for prototype 9B is only slightly less than a theoretical limit indicated by the solid line in the figure which is defined by a sinc function with an aperture size corresponding to the 127 μm pixel pitch of the array – a nearly ideal result. Such good MTF behavior is consistent with a prediction based on Monte Carlo simulation of x-ray energy deposition in a thin (i.e., 26 μm) layer of HgI2 which indicates relatively limited x-ray scattering. In the case of 11B, the empirically determined MTF is lower – possibly due to increased lateral spreading of charge for the thicker, 117 μm, photoconductive layer. For purposes of comparison, MTFs derived from published results for direct and indirect detection mammographic AMFPIs employing 200 μm and 150 μm thick a-Se and CsI:Tl converters, respectively, are also shown in the figure. The measured MTFs from the present HgI2 prototypes are seen to be superior to that of the CsI:Tl case, and comparable to (or greater than) that of the a-Se case.

Figure 5.

Measurements of MTF for prototypes 9B and 11B (open and closed symbols, respectively). The solid line is a sinc function based on a 127 μm aperture size. The MTF of a direct detection AMFPI with a 200 μm thick a-Se detector and the MTF for an indirect detection AMFPI with a 150 μm thick CsI:Tl detector (dashed and dashed-dot lines, respectively) are also shown. The plotted values for a-Se and CsI:Tl are based on published MTF results, (Zhao et al., 2003; El-Mohri et al., 2007) normalized to correspond to the 127 μm aperture of the MD88 array pixel pitch.

3.5. DQE

For each prototype, NPS was empirically determined, using the synthesized slit technique, (Giger et al., 1984; Maidment and Yaffe, 1994) through acquisition of 100 dark frames and 100 image frames at a constant exposure per frame (where dark or image frame corresponds to a data frame acquired in the absence or presence of radiation, respectively). The resulting NPS values, combined with the empirical results for MTF, allowed determination of DQE via the expression:

| Eq.(1) |

where is the mean x-ray fluence and is the average, dark-subtracted signal obtained from the region of interest in the image frames. The results are plotted as a function of exposure in Fig. 6. Two sets of theoretical predictions for DQE are also plotted in the figure. Predictions obtained from cascaded systems analysis calculations, (Cunningham et al., 1994; El-Mohri et al., 2007; Du et al., 2008) employing the empirically determined MTF, x-ray sensitivity, and additive electronic noise from the prototypes, are indicated by solid lines. In addition, theoretical upper limits on DQE (~57% and 95% for 9B and 11B, respectively), given by the product of the efficiency of x-ray detection (~59% and 97% for 9B and 11B, respectively) and the radiation Swank factor (~0.97 for both prototypes), are indicated by the dashed horizontal lines. (These efficiencies and factors were obtained from Monte-Carlo simulation of radiation transport.) At zero spatial frequency, both the empirically determined DQE and the cascaded systems analysis predictions are lower than the theoretical upper limit due to the relatively large electronic additive noise of the imaging system (~11,900 and 6,300 e [rms] for 9B and 11B, respectively). Moreover, the empirically determined DQE results are seen to be lower than the cascaded system analysis predictions – likely due to the presence of additional noise sources not accounted for in the calculations.

Figure 6.

(a) DQE results for prototype 9B at exposures of 0.45, 1.92 and 2.71 mR. (b) DQE results for prototype 11B at exposures of 0.51, 1.3 and 1.9 mR. In addition, cascaded systems calculations for 127 μm pitch AMFPIs employing a 200 μm thick direct detection a-Se converter and a 150 μm thick indirect detection CsI:Tl converter are also shown. In each figure, the solid line corresponds to a theoretical prediction for the corresponding HgI2 prototype obtained from cascaded systems analysis calculations. In addition, the dashed horizontal line corresponds to a theoretical upper limit on DQE(0) for the prototypes.

For both prototypes, the measured DQE exhibits no straightforward dependence on exposure. As seen in Fig. 6(a), the DQE for 9B increases as exposure increases from 0.45 to 1.92 mR due to the diminishing relative contribution of additive electronic noise. However, as also seen in the figure, at a higher exposure of 2.71 mR, DQE drops to a level similar to that at 0.45 mR. This pattern, which is particularly evident at low spatial frequencies, is also generally observed for 11B, as seen in Fig. 6(b). In that case, the magnitude of DQE is approximately constant from 0.51 to 1.3 mR, then drops when exposure increases further. This complex dependence on exposure is not understood but might also be related to the anomalous temporal noise. (Du et al., 2008)

The observed zero-frequency DQE of ~70% for prototype 11B is, to our knowledge, the highest value thus far reported for an AMFPI prototype incorporating polycrystalline mercuric iodide. For purposes of comparison, DQE results based on a cascaded systems analysis of AMFPIs employing CsI:Tl and a-Se converters under similar irradiation conditions at an exposure of 0.51 mR are also shown in Fig. 6(b). This analysis employed the type of model used in (Du et al., 2008) for direct converters and (El-Mohri et al., 2007) for indirect converters – with the same signal collection fill factor (100%) and electronic additive noise (3000 e) used for the CsI:Tl and a-Se calculations shown in Fig. 1, but for a pixel pitch of 127 μm. Despite a higher level of electronic additive noise, prototype 11B provides comparable DQE – a consequence of a lower effective work function for the HgI2 material.

3.6. Lag

Image lag for each prototype, quantified by the ratio of the residual signal from a dark frame to the full x-ray signal of a preceding image frame, was investigated using a technique described in (Zhao and Zhao, 2008) and the results are plotted in Fig. 7 as a function of frame number for several exposures. These results show no obvious dependence on exposure. The data for frame number 1 correspond to first frame lag. Prototype 11B is seen to exhibit less lag than 9B, with first frame lag ranging from ~17% to 20%. This high level of lag is comparable to that obtained from previous PIB prototypes (Du et al., 2008) and would not be suitable for tomosynthesis imaging due to the rapid image acquisition required for that application. By comparison, an a-Se prototype previously investigated for tomosynthesis applications exhibited first frame lag ranging from ~4% to 5%. (Zhao et al., 2008)

Figure 7.

(a) and (b) Lag measured for prototypes 9B and 11B, respectively. Results are shown as a function of the dark frame number following an image frame. The data were acquired at a frame time of ~0.5 s and results are shown for three exposures.

4. Summary and discussion

In this paper, we have reported a detailed investigation of the properties and performance of two direct detection, active matrix, flat-panel imager prototypes coated with a screen-printed form of polycrystalline HgI2 photoconductor and operated under mammographic irradiation conditions. These prototypes are notable by virtue of the use of relatively thin layers of photoconductive material as well as the absence of a barrier layer between the photoconductor and the array. The results obtained from these prototypes are encouraging. For both prototypes, WEFF values of ~19 eV, much lower than those obtained from CsI:Tl and a-Se AMFPIs, were observed at relatively low bias voltages. Moreover, prototype 11B exhibited a very low dark current, less than 0.1 pA/mm2, which is well below the level of ~1 pA/mm2 desirable for good AMFPI operation. (Antonuk, 2004) In addition, the MTF for prototype 9B was found to approach the limit imposed by the pixel pitch of the array. Finally, the prototypes exhibited good DQE, in one case demonstrating the highest level of DQE thus far reported for an AMFPI incorporating polycrystalline HgI2.

It is interesting to consider the potential DQE performance of AMFPIs employing polycrystalline HgI2 with pixel pitches more representative of those used in currently available commercial mammographic imagers (i.e., ~70 to 100 μm). Whereas it is straightforward to predict the signal performance (which will simply scale with pixel area) for such AMFPIs, extrapolation of the noise performance is more complicated. If one assumes that the relatively high electronic additive noise observed from the current prototypes (~6300 and ~11900 e) would be independent of pitch (and thus remain high), then the DQE of an HgI2 AMFPI with a smaller pitch would be lower (as predicted by cascaded systems calculations) than that of a-Se and CsI:Tl AMFPIs of similar pitch. However, another prototype AMFPI employing polycrystalline HgI2 has previously demonstrated a considerably lower level of electronic additive noise, ~2000 e (Du et al., 2008) – a level largely determined by the active matrix backplane and not by the photoconductor. Therefore, given the considerably lower WEFF offered by HgI2 compared to that of a-Se and CsI:Tl converters, and considering that additive noise should, ultimately, be largely limited by the design of the active matrix backplane irrespective of pitch, then it is reasonable to anticipate that AMFPIs based on HgI2 should be capable of offering better performance than current commerical a-Se and CsI:Tl mammographic AMFPIs.

In addition, given that advanced techniques for breast imaging, such as tomosynthesis and CT, tend to use higher energy x-ray spectra, (Nicolas et al., 2010; Yue-Houng et al., 2012) it is also of interest to consider the potential use of polycrystalline HgI2 photoconductors in these applications. In this case, the use of higher energy x-rays requires thicker layers of photoconductive material to maintain high DQE values, especially for breast CT which is typically performed at 80 kVp. Under these conditions, the advantage of low WEFF values offered by the HgI2 photoconductor (compared to the higher values exhibited by conventional converters such as CsI:Tl and a-Se) is maintained. (Du et al., 2009) Of course, some degradation in spatial resolution is expected as a result of k-fluorescence reabsorption as well as more scatter due to a thicker photoconductor. Fortunately, such degradation is not significant, resulting in MTF performance similar to, or even better than that of equivalent conventional converters. (Du et al., 2009) Overall, by virtue of a low WEFF and good spatial resolution, HgI2 photoconductors have the potential to provide similar, or even superior DQE performance compared to conventional x-ray converters under irradiation conditions relevant to tomosynthesis or breast CT.

However, a number of challenges remain to be addressed before this material can enter practical use. For example, the relatively high level of non-uniformity in the pixel signal response observed for both prototypes reduces the maximum exposure at which a prototype may be operated before saturation affects a substantial fraction of the pixels – a finding consistent with earlier studies. (Du et al., 2008) In addition, although the application of a simple gain correction usually resulted in a substantial reduction in non-uniformity, both prototypes exhibited indications of anomalous temporal variation in the pixel x-ray signal response. Such an effect reduces object detectability, since the gain correction would not be as effective in reducing spatial noise created by this variation. Moreover, the relatively high level of lag observed from the prototypes would introduce substantial ghosting – making the use of the present material problematic for tomosynthesis or breast CT applications. Given the promising results obtained from the current study, further investigations of these challenges are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Mr. Richard Choroszucha for assistance with the study. This work was supported by NIH grant NIH-R44-CA099104

Contributor Information

Hao Jiang, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, USA.

Qihua Zhao, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, USA.

Larry E. Antonuk, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, USA.

Youcef El-Mohri, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, USA.

Tapan Gupta, Radiation Monitoring Devices, Inc., Watertown, Massachusetts 02472, USA.

Reference

- Antonuk LE. In: Thin Film Transistors, Materials and Processes, Volume 1: Amorphous Silicon Thin Film Transistors. Kuo Y, editor. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Boston: 2004. pp. 395–484. [Google Scholar]

- Antonuk LE, Boudry J, Huang W, McShan DL, Morton EJ, Yorkston J, Longo MJ, Street RA. Demonstration of megavoltage and diagnostic x-ray imaging with hydrogenated amorphous silicon arrays. Med. Phys. 1992;19:1455–66. doi: 10.1118/1.596802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonuk LE, Jee K-W, El-Mohri Y, Maolinbay M, Nassif S, Rong X, Zhao Q, Siewerdsen JH, Street RA, Shah KS. Strategies to improve the signal and noise performance of active matrix, flat-panel imagers for diagnostic x-ray applications. Med. Phys. 2000;27:289–306. doi: 10.1118/1.598831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham IA, Westmore MS, Fenster A. A spatial-frequency dependent quantum accounting diagram and detective quantum efficiency model of signal and noise propagation in cascaded imaging systems. Med. Phys. 1994;21:417–27. doi: 10.1118/1.597401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du H, Antonuk LE, El-Mohri Y, Zhao Q, Su Z, Yamamoto J, Wang Y. Investigation of the signal behavior at diagnostic energies of prototype, direct detection, active matrix, flat-panel imagers incorporating polycrystalline HgI2. Phys. Med. Biol. 2008;53:1325–51. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/5/011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mohri Y, Antonuk LE, Jee K-W, Kang Y, Li Y, Sawant A, Su Z, Wang Y, Yamamoto J, Zhao Q. Evaluation of novel direct and indirect detection active matrix, flat-panel imagers (AMFPIs) for mammography. Proc. SPIE. 2003;5030:168–80. [Google Scholar]

- El-Mohri Y, Antonuk LE, Zhao Q, Wang Y, Li Y, Du H, Sawant A. Performance of a high fill factor, indirect detection prototype flat-panel imager for mammography. Med. Phys. 2007;34:315–27. doi: 10.1118/1.2403967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita H, Tsai DY, Itoh T, Doi K, Morishita J, Ueda K, Ohtsuka A. A simple method for determining the modulation transfer function in digital radiography. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 1992;11:34–9. doi: 10.1109/42.126908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giger ML, Doi K, Metz CE. Investigation of basic imaging properties in digital radiography. 2. Noise Wiener spectrum. Med. Phys. 1984;11:797–805. doi: 10.1118/1.595583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartsough NE, Iwanczyk JS, Patt BE, Skinner NL. Imaging performance of mercuric iodide polycrystalline films. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science. 2004;51:1812–6. [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Antonuk LE, Berry J, Maolinbay M, Martelli C, Mody P, Nassif S, Yeakey M. An asynchronous, pipelined, electronic acquisition system for active matrix flat-panel imagers (AMFPIs) Nucl. Instrum. Meth. Phys. Res. A. 1999;431:273–84. [Google Scholar]

- Jee K-W, Antonuk LE, El-Mohri Y, Zhao Q. System performance of a prototype flat-panel imager operated under mammographic conditions. Med. Phys. 2003;30:1874–90. doi: 10.1118/1.1585051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang H, Zhao Q, El-Mohri Y, Antonuk LE, Gupta T. Investigation of an active matrix flat-panel imager (AMFPI) employing a thin layer of polycrystalline HgI2 photoconductor for mammographic imaging. Proc. SPIE. 2012;8313:83130G. [Google Scholar]

- Kang Y, Antonuk LE, El-Mohri Y, Hu L, Li Y, Sawant A, Su Z, Wang Y, Yamamoto J, Zhao Q. Examination of PbI2 and HgI2 photoconductive materials for direct detection, active matrix, flat-panel imagers for diagnostic x-ray imaging. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science. 2005;52:38–45. [Google Scholar]

- Maidment ADA, Yaffe MJ. Analysis of the spatial-frequency-dependent DQE of optically coupled digital mammography detectors. Med. Phys. 1994;21:721–9. doi: 10.1118/1.597331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas DP, Karen KL, Shonket R, Shih-Ying H, Laurei AB, Wayne LM, John MB. Contrast-enhanced Dedicated Breast CT:Initial Clinical Experience. Radiology. 2010;256:714–23. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10092311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieber M, Hermon H, Zuck A, Vilensky A, Melekhov L, Shatunovsky R, Meerson E, Saado Y. Polycrystalline mercuric iodide detectors. Proceedings of SPIE. 1999;3770:146–55. [Google Scholar]

- Schieber M, Hermon H, Zuck A, Vilensky A, Melekhov L, Shatunovsky R, Meerson E, Saado Y, Lukach M, Pinkhasy E, Ready SE, Street RA. Thick films of X-ray polycrystalline mercuric iodide detectors. Journal of Crystal Growth. 2001;225:118–23. [Google Scholar]

- Simon M, Ford RA, Franklin AR, Grabowski SP, Menser B, Much G, Nascetti A, Overdick M, Powell MJ, Wiechert DU. Analysis of lead oxide (PbO) layers for direct conversion X-ray detection. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science. 2005;52:2035–40. [Google Scholar]

- Stone MF, Zhao W, Jacak BV, O’Connor P, Yu B, Rehak P. The x-ray sensitivity of amouphous selenium for mammography. Med. Phys. 2002;29:319–24. doi: 10.1118/1.1449874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street RA, Ready SE, van Schuylenbergh K, Ho J, Boyce JB, Nylen P, Shah K, Melekhov L, Hermon H. Comparison of PbI2 and HgI2 for direct detection active matrix x-ray image sensors. Journal of Applied Physics. 2002;91:3345–55. [Google Scholar]

- Su Z, Antonuk LE, El-Mohri Y, Hu L, Du H, Sawant A, Li Y, Wang Y, Yamamoto J, Zhao Q. Systematic investigation of the signal properties of polycrystalline HgI2 detectors under mammographic, radiographic, fluoroscopic and radiotherapy irradiation conditions. Phys. Med. Biol. 2005;50:2907–28. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/50/12/012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue-Houng H, David AS, Wei Z. The Effect of Amorphous Selenium Thickness On Imaging Performance of Contrast Enhanced Digital Breast Tomosynthesis. Breast Imaging. 2012;7361:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zentai G, Partain L, Pavlyuchkova R. Dark current and DQE improvements of mercuric iodide medical imagers. Proceedings of SPIE. 2007;6510:65100Q-1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zentai G, Partain L, Pavyluchova R, Proano C, Breen B, Taieb A, Dagan M, Schieber M, Gilboa H. Mercuric Iodide Medical Imagers for Low Exposure Radiography and Fluoroscopy. Proc. SPIE. 2004;5368:200–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Zhao W. Imaging performance of an amorphous selenium digital mammography detector in a breast tomosynthesis system. Med. Phys. 2008;35:1978–87. doi: 10.1118/1.2903425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Antonuk LE, El-Mohri Y, Wang Y, Du H, Sawant A, Su Z, Yamamoto J. Performance evaluation of polycrystalline HgI2 photoconductors for radiation therapy imaging. Med. Phys. 2010;37:2738–48. doi: 10.1118/1.3416924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Ji WG, Debrie A, Rowlands JA. Imaging performance of amorphous selenium based flat-panel detectors for digital mammography: characterization of a small area prototype detector. Med. Phys. 2003;30:254–63. doi: 10.1118/1.1538233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuck A, Schieber M, Khakhan O, Burshtein Z. Near single-crystal electrical properties of polycrystalline HgI2 produced by physical vapor deposition. IEEE Transactions on Nuclear Science. 2003;50:991–7. [Google Scholar]