Abstract

The aim of this pilot study was to assess the effectiveness of buprenorphine among marginalized opioid dependent individuals in terms of retention in and cycling in and out of a harm-reduction program. This pilot study enrolled 100 participants and followed them from November 2005 to July 2008. The overall proportion of patients retained in the program at the end of 3, 6, 9, and 12 months was 68%, 63%, 56%, and 42%, respectively. This pilot study demonstrated that buprenorphine could be successfully used to treat marginalized heroin users.

Introduction

Despite a high prevalence of opioid-dependent individuals in the United States - 1.6 million persons abuse or are dependent on prescription opioids, whereas 323,000 abuse or are dependent on heroin – 80% of them remain untreated.1 The lack of access to methadone treatment is an international problem. In the United States, the strict regulatory environment and long waiting lists deter opioid-dependent patients from enrolling.2,3 The advent of buprenorphine and the passage of the Drug Addiction Treatment Act in 2000 have changed the opioid treatment delivery system by granting physicians the ability to administer office-based opioid treatment, thereby giving patients greater access to treatment.4 However, buprenorphine treatment for heroin addiction has not expanded as widely as expected. Its adoption has been somewhat slow5 and street-involved heroin users, in particular, are less likely to receive it as compared to prescription opioid misusers. Moreover, a study using administrative data from Medicaid between 2007 and 2009 showed that the use of buprenorphine was significantly more common in rural communities, and 64% of buprenorphine use was in office-based settings, suggesting the need for efforts to increase buprenorphine use among urban populations.6

During the past nine years, buprenorphine has been successfully prescribed in various medical venues, including primary care physicians’ offices7, clinics, and specialized programs such as homeless centers.8, 9 The office-based prescribing of buprenorphine in various medical venues gives opioid users the opportunity to be treated in relatively regulation-free environments without confinement to residential facilities or having to attend regulated clinics daily. Since untreated addiction contributes to the spread of infectious disease and crime, it is important to have as many options as possible for treatment. In other countries, such as France, rapid access to buprenorphine has led to improved health outcomes in opioid-dependent drug users.10 In France, the prevalence of HIV was reduced from 40% in 1996 to 11% in 2006,11 and opioid overdose fatalities have declined substantially (by 79%) since buprenorphine introduction in 1996.12 Access to buprenorphine has been shown to improve adherence13 and virological response to HIV treatment.14

In the US, buprenorphine is available in two formulations: buprenorphine alone (Subutex) and buprenorphine in combination with naloxone (Suboxone). Most commonly, Suboxone is prescribed in the US in the hopes of reducing diversion of the medication for illicit use. Specifically, if the medication is crushed and used by injection, naloxone becomes effective as an opioid antagonist, which can reduce the agonist effects produced by buprenorphine itself and/or precipitates withdrawal in an opioid-dependent individual.15 While buprenorphine treatment is primarily accessible through office-based systems, these programs are usually too expensive for marginalized populations.16 And methadone maintenance programs, though financially more accessible for low-income patients, are characterized by tight regulatory controls and long waiting lists, both of which are associated with high dropout and relapse rates.17 As it is urgent to increase buprenorphine access to marginalized populations of drug users who are more at risk of comorbidities and infectious disease transmission, the justification for administering buprenorphine through a program tailored for marginalized populations with unstable lifestyles is appropriate.

The goal of this pilot study was to demonstrate that buprenorphine could be successfully delivered to heroin users from lower socioeconomic populations (e.g., marginally housed, l,, ow-income individuals, etc.). This harm reduction or low-threshold model consisted of prescribing buprenorphine based on an immediate assessment of a patient’s appropriateness for the program and more flexible criteria regarding drug use. For example, while most patients intended to stop heroin use, a few entered the program in order to better manage use. Others had little or no intention of reducing cocaine or alcohol use. Patients were initially recruited at syringe exchange programs and, aside from a few exclusions, were welcome to participate without expressing a commitment to abstinence or counseling. Since previous papers have shown that buprenorphine can be delivered in a less regulated system for drug users, we found it relevant to assess the effectiveness of access to buprenorphine treatment in a harm reduction setting in terms of retention in treatment and to investigate determinants of cycling in and out of treatment.

Material and Methods

Study population

This pilot study started on November 21st, 2005 and lasted until July 28th, 2008 (32 months), and enrolled 100 participants in the Harm Reduction Coalition (HRC) Buprenorphine Maintenance Harm Reduction Program.

Program design

Patients were recruited initially through referrals from syringe exchange programs; but as the program progressed, patients often referred their friends. A few methadone patients (n=7) were accepted, but the program primarily targeted heroin users. A few potential patients were referred elsewhere, as the prescribing physician was only able to manage a small number of new patients each week; others were referred elsewhere because they had chronic pain that the physician did not feel equipped to manage or were pregnant.

The initial visit was either at a syringe exchange or at the HRC, and the patient was referred either by syringe exchange staff or fellow drug users. A careful history was taken, with particular attention to the patient’s history of drug use. If the patient was appropriate and willing, an initial prescription was given of the formulation marketed as Suboxone, consisting of 14 tablets, each composed of 8 mg of buprenorphine and 2 mg of naloxone in a 4 to 1 ratio. The patient was also given induction instructions and the physician’s cell phone number, and a follow-up appointment was scheduled for one week after the initial visit. Every effort was made to make phone contact with the patient within 24 to 48 hours. After an induction period of one week, a determination of buprenorphine dose for maintenance was made. Patients then received medication for 1 to 2 weeks during stabilization, and occasionally longer depending on the circumstances. The goal for most patients was monthly visits with the physician, although some were asked to come more frequently. Referrals for counseling and/or support were made for all patients, though attendance was not a requirement. Syringe exchange programs were sources of psychosocial support for many patients. Other sources included 12-step groups, drug treatment, or psychiatric care. Some patients received no formal psychosocial support, except from the prescribing physician. Many patients had a primary physician. For those who did not, referrals were made for primary care with an emphasis on blood tests. No other medications were prescribed aside from an occasional stool softener.

After the induction period, patients received a prescription, generally for 30 days. During the course of the 30 days, the patient was presumed to be actively in the program. There was a grace period of 15 days thereafter; patients not returning after 45 days were classified as inactive. When patients missed appointments, contact attempts were made to reschedule them. If they returned after 45 days, they were welcomed back and started a new induction and new prescription period or cycle and prompted to discuss what had happened during the interim.

No urine toxicology was done either initially or during the follow-up visits. It was made clear to all patients that they would not be penalized for continued drug use in order to minimize barriers to return to treatment.

Data collection

The physician kept a database of visits, demographic characteristics, insurance status, dosage, and certain aspects of the patient’s history of drug use. An active period was defined as the period of time a patient had a prescription for buprenorphine, generally 30 days plus a 15 day grace period; if the patient was not seen during the 45 days, the patient was thereafter defined as being inactive until they returned to the program.

Total duration of retention in the program was considered as the total time the patient was in prescription episodes and in non-prescription episodes. The total duration in an active period during the study was the cumulative amount of time the patient was in prescription episodes. One prescription episode started at the 1st day of the buprenorphine prescription and lasted to the 45th day. This episode was considered an active prescription. Non-prescription episodes (or inactive periods) were the number of days between the end of a prescription episode and the beginning of the next prescription episode.

To explore the various psychosocial and clinical treatment experiences of patients receiving buprenorphine maintenance within the program, we selected 20 patients for ethnographic interviews performed at the Harm Reduction Coalition Center.

Statistical analyses

First, we compared the group of patients who requested detoxification with buprenorphine to those who requested maintenance with buprenorphine in regard to their sociodemographic data, history of drug use, and opioid dependence treatment. Then, among patients who applied for maintenance treatment, we compared individuals who did not enter the maintenance program and those who entered the maintenance program. Finally, we compared the group of patients who were in an active period and the group in an inactive period or nonprescription period on the last day of the pilot. All comparisons were performed using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables, and chi-square or Fisher’s tests for dichotomous ones. Tests were two-sided, with a significance level fixed at α=0.05. The SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and Stata version 10.1 (Stata Corp, Texas, USA) for Windows software packages were used for the analyses.

Results

Baseline descriptive analysis

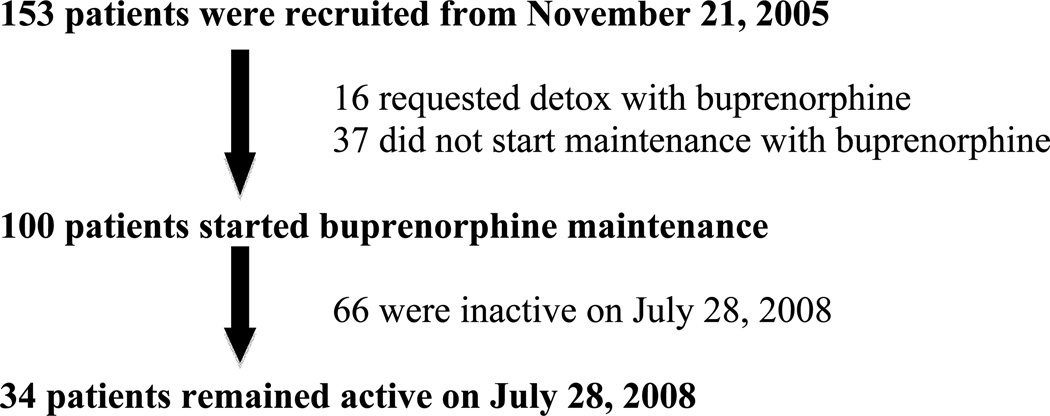

One hundred fifty-three applicants were recruited for the pilot project during the study period. Sixteen applied for detoxification from opioids using buprenorphine, and 137 applied for buprenorphine maintenance (Figure 1). Among the individuals who applied for buprenorphine maintenance (n=137), 30% were women, half were Hispanic, one-quarter were Caucasian, and one-quarter were African American. Eighty percent had health insurance; of those with insurance, 73% were insured by Medicaid. Almost half were employed, with 40% only part time and most of them “off the books.”

Figure 1.

Summary of the status of 153 patients during the course of the study

Regarding drug use, half of them reported being intravenous heroin users, 39% intranasal heroin users, and 11% used opioids orally. Most of the participants reported using heroin (86%), 7% prescription opioids, and 7% reported being in a methadone program. The mean age for those applying for buprenorphine maintenance was 40 years and the mean age for the first misused opioid was 21 years. More than half of the sample (58%) reported having already participated in a methadone maintenance program. The group requesting detoxification was composed primarily of White uninsured youth, all of whom injected heroin and were associated with a facility serving youth. Most of them were homeless. Few had any history of methadone treatment. Variables related to ethnicity (African American, Latino, and White), insurance, and employment were significantly different (P < .05 for the 1-tailed test) in patients who entered buprenorphine detoxification compared to those who entered buprenorphine maintenance. Regarding drug use and treatment history, the detoxification group was more likely to use opioids by injection, to use heroin, and to be younger, and less likely to have a history of methadone maintenance treatment or health insurance.

Follow-up and cycling in and out

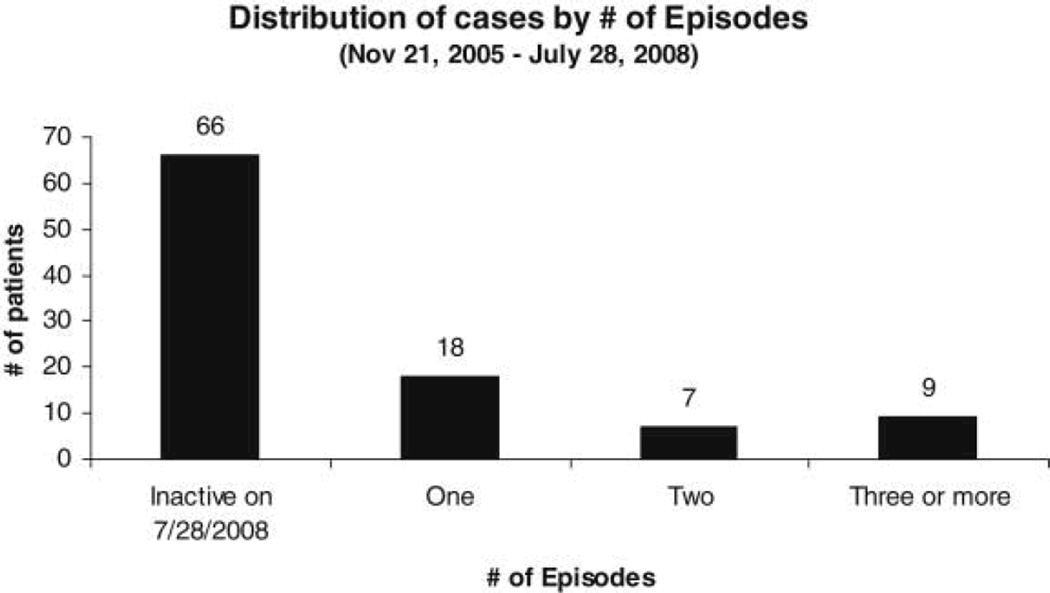

Of the 137 applicants who applied for maintenance, 37 (24.2%) did not report back after the intake interview where they received one prescription. Therefore, 100 applicants officially entered buprenorphine maintenance (Figure 1). No differences were found between individuals who did not enter buprenorphine maintenance and those who did enter maintenance. Between November 2005 and July 2008, the maximum number of active and inactive prescription episodes for patients was 8 active prescription episodes and 7 inactive episodes. Of the 66 patients who were inactive at the close of the study, 60% were lost to follow-up or in prison. About 40% left voluntarily, either transferring to other buprenorphine providers, entering methadone treatment, tapering from Suboxone, or leaving the area. As summarized in Figure 2, at the end of the pilot study, 66 patients were in a nonprescription or inactive episode; 18 patients had remained continuously active; 7 had two episodes of treatment; and 9 had three or more episodes of treatment. When taking into account prescription and nonprescription episodes, the median cumulative duration of program participation for the 100 participants who entered buprenorphine maintenance was 12.3 months. Overall, the proportion of patients retained in the program at the end of 3, 6, 9, and 12 months was 68%, 63%, 56%, and 42%, respectively. When taking into account only active periods, the median duration of treatment with buprenorphine was 3 months. The proportion of patients still in the first active period at the end of 3, 6, 9, and 12 months was 42%, 31%, 28%, and 20%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Distribution of 100 patients who began buprenorphine maintenance by number of active prescription episodes

Quite commonly, patients stretched out the intervals between prescriptions, either by lowering doses, or by stopping medication; they returned with reports of craving or, more commonly, relapse. In addition to drug use during inactive periods, some discussed occasional heroin use and a few were open about cocaine and alcohol problems while in treatment. Several patients disclosed giving a dose of medication to help a friend in withdrawal; in fact, several patients came to the program because they had been impressed with a dose given to them by another patient.

Comparison between active and inactive patients at the end of the study

Table 2 shows that the only statistically significant variables between active and inactive patients as of July 28, 2008 was within the ethnic groups – African American and Latino – namely, a greater percentage of African American patients were active and a greater percentage of Latino patients were inactive at the end of the study. It should be noted that African American patients were the modal group of active patients. However, regarding drug use and treatment history, we found no statistically significant differences between active and inactive patients as of July 28, 2008, when considering routes of administration, drugs used, variables related to age of first narcotics use, age first applied for buprenorphine treatment, and age differential between first drug use and applying for buprenorphine treatment. Although there was a tendency for those with past enrollment in a methadone maintenance treatment program (MMTP) to remain in buprenorphine treatment, the difference between the active and inactive subjects was not statistically significant. The median daily dose of buprenorphine was 16 mg in active patients as well as in inactive patients.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis for active versus inactive patients on July 28, 2008.

| Variable | Active (n=34) |

Inactive (n=66) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male (%) | 23 (68%) | 47 (71%) | 70 (70%) |

| Female (%) | 11 (32%) | 19 (29%) | 30 (30%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| African American (%)** | 14 (41%) | 14 (21%) | 37 (24.2%) |

| Latino (%)** | 10 (29%) | 33 (50%) | 62 (40.5%) |

| Caucasian (%) | 10 (29%) | 18 (27%) | 52 (34.0%) |

| Multi-racial (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| Insured (%) | 30 (88%) | 53 (80%)++ | 83 (83%)+++ |

| Employed (%) | 17 (50%) | 30 (46%) | 47 (47%) |

| Route of administration | |||

| Injection (%) | 11 (32%) | 34 (52%) | 45 (45%) |

| Oral (%) | 6 (18%) | 7 (11%) | 13 (13%) |

| Inhale (%) | 17 (50%) | 25 (38%) | 42 (42%) |

| Drug used | |||

| Heroin (%) | 25 (74%) | 58 (88%) | 83 (83%) |

| Methadone (%) | 3 (9%) | 4 (6%) | 7 (7%) |

| Vicodin (%) | 5 (15%) | 4 (6%) | 9 (9%) |

| Mean Age applied Buprenorphine TX (S.D) | 43 (12.7) | 39.1 (12.1) | 40.5 (12.4) |

| Mean Age 1st misused opioid (S.D) | 22.1 (8.2) | 20.6 (7.4) | 21.1 (7.6) |

| Past MMTP (%) | 23 (68%) | 32 (49%) | 55 (55%) |

p<.05

Results from the ethnographic interviews

The 20 selected interviewees had previously been in different types of drug treatment programs: 12 had been in detoxification, 14 in methadone treatment, and 11 in various therapeutic communities. Others had participated in 12 step programs and two had received pain management. Since Suboxone is an alternative to methadone as a maintenance medication for the treatment of opioid dependence, and many of the interviewees had had unsuccessful experiences with methadone, we inquired about their attitudes concerning the methadone program. Frequency of clinic visits and urine collection procedures were common complaints. They were also cognizant of the stigmatization of the program in their neighborhoods. Regarding the program, all patients were appreciative that the Suboxone Maintenance Harm Reduction program was organized as an office based practice similar to the treatment of other illnesses with private scheduled physician appointments, prescriptions for Suboxone filled in pharmacies and taking the medication in the privacy of their homes. Patients filled their prescriptions with Medicaid or insurance.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first pilot study using buprenorphine in a harm reduction setting in the United States. Interestingly, for patients who started buprenorphine maintenance, the retention rate corroborates those found in previous studies of agonist maintenance therapy.8, 18 In our sample, 63% of the patients were still in the program after 6 months and 31% were continuously maintained on buprenorphine during the first 6-month period of treatment. After 12 months, 42% were still in the program. Bell and colleagues found in a sample of 477 patients entering a methadone maintenance program that 52% were still in treatment after 6 months.18 In addition, a study from the Buprenorphine Pilot Program initiated in 2003 in San Francisco, aiming at supporting the use of buprenorphine across the San Francisco Department of Public Health system of care, showed a one-year retention rate of 61%.8 This higher retention rate may be explained by a more stable and less marginalized population.

One secondary result of the current study concerns the impact of the pilot program on those who applied only for detoxification. Indeed, it is interesting to note that those patients who entered the detoxification program were less likely to have insurance or employment and were younger. In the context of marginalized populations, this harm reduction program may be an entry point to longer term treatment, even if the choice of detoxification is often made because of difficulties getting financial support to pay for long-term maintenance, as shown previously.19

Regarding the group of patients who entered buprenorphine maintenance, the comparison between participants who were still receiving buprenorphine from the program at the end of the study and those who dropped out shows that African American patients are more likely to be retained in treatment. This result supports the hypothesis that was posited in a previous study in New York City showing that African Americans were more likely to enter into opioid dependence treatment and stop using heroin at the end of an inpatient program.20 Although the context is different, the interpretation could be that ethnic factors are associated with different needs and responses to drug treatment modalities.21 Alternatively, because some studies have shown that African Americans have more difficulty accessing treatment for heroin dependence,22 it may be that they show greater treatment success when they do enter effective programs.

The originality of this program relies on a more tailored approach for socially marginalized patients wishing to stop or reduce heroin use with the use of buprenorphine. The effectiveness of this low-threshold program for such populations has already been shown by Perreault and colleagues through a methadone program in Montreal.23 These authors demonstrated the importance and value of flexible intervention programs in reaching a marginalized clientele, especially regarding their high exposure to HIV. Indeed, access to buprenorphine is known to have a positive impact on HIV infection outcomes14, 24 and to reduce HIV risk behaviors.25 Also, treating homeless opioid-dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting has been found to be equally effective as treating housed patients with respect to retention, decreased opioid use, and access to care.9

This pilot study adds to previous results demonstrating the feasibility and positive effects of expanding buprenorphine programs to opioid-dependent individuals with higher risk of blood-borne disease transmission, lower socioeconomic level, increased criminality, and higher prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities.10 In the current study, therapeutic outcomes for marginalized patients were comparable to those who self-select office-based treatment with buprenorphine and those treated in methadone programs.4 Our project, which was based on a harm reduction model, aimed to attract more marginalized populations, including younger clients, those with more chaotic lifestyles, and long-term heroin users with either no experience with methadone or with an unsuccessful treatment history with others treatment modalities. We believe, though it remains to be shown in future studies, that maintaining patients in the program, despite the possible cycling in and out of treatment, will be beneficial in the long term. This cumulative duration effect on positive health outcomes for patients who cycle in and out of treatment is well documented in terms of the virological success of HIV treated patients14 and on reductions in risky behaviors and decreases in opioid use.26

As is widely known, there is a risk of buprenorphine diversion either by injection in patients who receive the medication27 or on the black market as found both in the French and American context within the phenomenon of “doctor shopping”.28, 29 Although the buprenorphine/naloxone combination was developed to deter injecting practices, some studies have shown that Suboxone is diverted.30, 31 Ethnographic studies are needed to clarify the role, use and extent of diverted Suboxone; however, it is known that buprenorphine as a partial mu opioid agonist has a lower risk of overdose compared to a full opioid agonist.32 However, in the US, the most commonly diverted prescription opioids seem to be oxycodone, hydrocodone, and methadone.33 Interestingly, two studies have shown that street methadone is more widely used than street buprenorphine,34 and that both drugs are largely used as self-medication for detoxification, to reduce the use of other opioids, or to alleviate withdrawal symptoms.35, 36 Our findings suggest that expanding access to buprenorphine via harm reduction programs may be a feasible, efficient, and low-risk intervention for public health in the US context.

Some limitations of our study should be acknowledged. Although the findings of this pilot project are clearly promising, it would have been interesting to collect further data on psychiatric comorbidities, as well as criminality and risky behaviors related to HIV and HCV transmission. Furthermore, collection of urine drug levels throughout the study would have been informative, and more intensive efforts to locate study dropouts possibly would have led to greater treatment success.

In sum, the majority of heroin users, whether injectors or inhalers, who were recruited for the Harm Reduction Coalition Buprenorphine Maintenance Program had a history of participation in other forms of treatment, including in therapeutic communities, 12-step programs, group therapies, and methadone. A different approach to treatment that incorporated harm reduction principles was implemented to determine whether those recruited would cooperate in such a pilot. The encouraging results from this pilot study support the initiation of a more comprehensive study in order to confirm the benefits of expanding access to buprenorphine for marginalized populations.

Table 1.

Descriptive analysis for applicants for detoxification with buprenorphine versus those who applied for buprenorphine maintenance at the initiation of the pilot study.

| Variable | Group I (n=16) |

Group II (n=137) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male (%) | 11 (68.8%) | 96 (70.1%) | 107 (69.9%) |

| Female (%) | 5 (31.3%) | 41 (30.0%) | 46 (30.1%) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| African American (%) | 1 (6.3%) | 36 (26.3%) | 37 (24.2%) |

| Latino (%)** | 1 (6.3%) | 61 (44.5%) | 62 (40.5%) |

| Caucasian (%)** | 14 (87.5%) | 38 (27.7%) | 52 (34.0%) |

| Multiracial (%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.5%) | 2 (1.3%) |

| Insured (%)** | 2 (12.5%) | 108 (80.0%)++ | 110 (72.8%)+++ |

| Employed (%)** | 1 (6.3%) | 62 (45.3%) | 63 (41.2%) |

| Route of administration | |||

| Injection (%)** | 16 (100%) | 68 (49.6%) | 84 (54.9%) |

| Oral (%) | 0 | 15 (10.9%) | 15 (9.8%) |

| Inhale (%) | 0 | 54 (39.4%) | 54 (35.3%) |

| Drug used | |||

| Heroin (%) | 16 (100%) | 117 (85.4%) | 133 (86.9%) |

| Methadone (%) | 0 | 9 (6.6%) | 9 (5.9%) |

| Vicodin (%) | 0 | 10 (7.3%) | 10 (6.5%) |

| Mean age applied for buprenorphine tx (S.D) ** | 23.4 (5.8) | 40.2 (12.3) | 38.4 (12.9) |

| Mean age 1st misused opioid (S.D) ** | 18.8 (2.5) | 21.3 (7.9) | 21.0 (7.6) |

| Past MMTP (%)** | 2 (12.5%) | 80 (58.4%) | 82 (53.6%) |

Group I: applied for detoxification

Group II: applied for maintenance

based on n=135

based on n=151

P < .05

Acknowledgments

The study was funded by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYCDOHMH); this study was approved by the IRB at the NYCDOHMH.

References

- 1.Sullivan LE, Fiellin DA. Narrative review: buprenorphine for opioid-dependent patients in office practice. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:662–670. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-9-200805060-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman SR, Tempalski B, Cooper H, Perlis T, Keem M, Friedman R, Flom PL. Estimating numbers of injecting drug users in metropolitan areas for structural analyses of community vulnerability and for assessing relative degrees of service provision for injecting drug users. J Urban Health. 2004;81:377–400. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterson JA, Schwartz RP, Mitchell SG, Reisinger HS, Kelly SM, O'Grady KE, Brown BS, Agar MH. Why don't out-of-treatment individuals enter methadone treatment programmes? Int J Drug Policy. 2010;21:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kraus ML, Alford DP, Kotz MM, Levounis P, Mandell TW, Meyer M, Salsitz EA, Wetterau N, Wyatt SA. Statement of the American Society of Addiction Medicine Consensus Panel on the Use of Buprenorphine in Office-Based Treatment of Opioid Addiction. J Addict Med. 2011;5:254–263. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182312983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ducharme LJ, Abraham AJ. State policy influence on the early diffusion of buprenorphine in community treatment programs. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stein BD, Gordon AJ, Sorbero M, Dick AW, Schuster J, Farmer C. The impact of buprenorphine on treatment of opioid dependence in a Medicaid population: Recent service utilization trends in the use of buprenorphine and methadone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sohler NL, Li X, Kunins HV, Sacajiu G, Giovanniello A, Whitley S, Cunningham CO. Home- versus office-based buprenorphine inductions for opioid-dependent patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hersh D, Little SL, Gleghorn A. Integrating buprenorphine treatment into a public healthcare system: the San Francisco Department of Public Health's office-based Buprenorphine Pilot Program. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43:136–145. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.587704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alford DP, LaBelle CT, Richardson JM, O'Connell JJ, Hohl CA, Cheng DM, Samet JH. Treating homeless opioid dependent patients with buprenorphine in an office-based setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:171–176. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0023-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrieri MP, Amass L, Lucas GM, Vlahov D, Wodak A, Woody GE. Buprenorphine use: the international experience. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(Suppl 4):S197–S215. doi: 10.1086/508184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emmanuelli J, Desenclos JC. Harm reduction interventions, behaviours and associated health outcomes in France, 1996–2003. Addiction. 2005;100:1690–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auriacombe M, Fatseas M, Dubernet J, Daulouede JP, Tignol J. French field experience with buprenorphine. Am J Addict. 2004;13(Suppl 1):S17–S28. doi: 10.1080/10550490490440780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moatti JP, Carrieri MP, Spire B, Gastaut JA, Cassuto JP, Moreau J. Adherence to HAART in French HIV-infected injecting drug users: the contribution of buprenorphine drug maintenance treatment. The Manif 2000 study group. Aids. 2000;14:151–155. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200001280-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roux P, Carrieri MP, Cohen J, Ravaux I, Poizot-Martin I, Dellamonica P, Spire B. Retention in opioid substitution treatment: a major predictor of long-term virological success for HIV-infected injection drug users receiving antiretroviral treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1433–1440. doi: 10.1086/630209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Comer SD, Sullivan MA, Vosburg SK, Manubay J, Amass L, Cooper ZD, Saccone P, Kleber HD. Abuse liability of intravenous buprenorphine/naloxone and buprenorphine alone in buprenorphine-maintained intravenous heroin abusers. Addiction. 2010;105:709–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02843.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenheck R, Kosten T. Buprenorphine for opiate addiction: potential economic impact. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63:253–262. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King VL, Burke C, Stoller KB, Neufeld KJ, Peirce J, Kolodner K, Kidorf M, Brooner RK. Implementing methadone medical maintenance in community-based clinics: disseminating evidence-based treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:312–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell J, Burrell T, Indig D, Gilmour S. Cycling in and out of treatment; participation in methadone treatment in NSW, 1990–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amodeo M, Lundgren L, Chassler D, Witas J. High-frequency users of detoxification: who are they? Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43:839–849. doi: 10.1080/10826080701800990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roux P, Tindall C, Fugon L, Murray J, Vosburg SK, Saccone P, Sullivan MA, Manubay JM, Cooper ZD, Jones JD, Foltin RW, Comer SD. Impact of inpatient research participation on subsequent heroin use patterns: Implications for ethics and public health. Addiction. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03664.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bernstein E, Bernstein J, Tassiopoulos K, Valentine A, Heeren T, Levenson S, Hingson R. Racial and ethnic diversity among a heroin and cocaine using population: treatment system utilization. J Addict Dis. 2005;24:43–63. doi: 10.1300/j069v24n04_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bourgois P, Martinez A, Kral A, Edlin BR, Schonberg J, Ciccarone D. Reinterpreting ethnic patterns among white and African American men who inject heroin: a social science of medicine approach. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perreault M, Rousseau M, Mercier C, Lauzon P, Gagnon C, Cote P. Accessibility to methadone substitution treatment: the role of a low-threshold program. Can J Public Health. 2003;94:197–200. doi: 10.1007/BF03405066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spire B, Lucas GM, Carrieri MP. Adherence to HIV treatment among IDUs and the role of opioid substitution treatment (OST) Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sullivan LE, Fiellin DA. Buprenorphine: its role in preventing HIV transmission and improving the care of HIV-infected patients with opioid dependence. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:891–896. doi: 10.1086/432888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gossop M, Marsden J, Stewart D, Rolfe A. Treatment retention and 1 year outcomes for residential programmes in England. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;57:89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roux P, Villes V, Blanche J, Bry D, Spire B, Feroni I, Carrieri MP. Buprenorphine in primary care: Risk factors for treatment injection and implications for clinical management. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;97:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dasgupta N, Bailey EJ, Cicero T, Inciardi J, Parrino M, Rosenblum A, Dart RC. Post-marketing surveillance of methadone and buprenorphine in the United States. Pain Med. 2010;11:1078–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feroni I, Peretti-Watel P, Paraponaris A, Masut A, Ronfle E, Mabriez JC, Obadia Y. French general practitioners' attitudes and prescription patterns toward buprenorphine maintenance treatment: does doctor shopping reflect buprenorphine misuse? J Addict Dis. 2005;24:7–22. doi: 10.1300/J069v24n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mammen K, Bell J. The clinical efficacy and abuse potential of combination buprenorphine-naloxone in the treatment of opioid dependence. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10:2537–2544. doi: 10.1517/14656560903213405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruce RD, Govindasamy S, Sylla L, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Lack of reduction in buprenorphine injection after introduction of co-formulated buprenorphine/naloxone to the Malaysian market. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:68–72. doi: 10.1080/00952990802585406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wesson DR, Smith DE. Buprenorphine in the treatment of opiate dependence. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42:161–175. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2010.10400689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cicero TJ, Inciardi JA, Munoz A. Trends in abuse of Oxycontin and other opioid analgesics in the United States: 2002–2004. J Pain. 2005;6:662–672. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gwin Mitchell S, Kelly SM, Brown BS, Schacht Reisinger H, Peterson JA, Ruhf A, Agar MH, O'Grady KE, Schwartz RP. Uses of diverted methadone and buprenorphine by opioid-addicted individuals in Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Addict. 2009;18:346–355. doi: 10.3109/10550490903077820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bazazi AR, Yokell M, Fu JJ, Rich JD, Zaller ND. Illicit use of buprenorphine/naloxone among injecting and noninjecting opioid users. J Addict Med. 2011;5:175–180. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182034e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ompad DC, Fuller CM, Chan CA, Frye V, Vlahov D, Galea S. Correlates of illicit methadone use in New York City: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:375. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]