Abstract

Background

Adolescent selective intervention programs for alcohol have focused on the identification of youth at risk as a function of personality and associated alcohol-related cognitions. Research into the role of personality, drinking motivations, and alcohol-related outcomes has generally focused exclusively on motives to drink. We expand on this literature by focusing on both motives to drink and motives not drink across time from adolescence to early adulthood in a community sample.

Methods

Using three waves of data from three cohorts from the Rutgers Health and Human Development Project (n = 1380; 49.4% women), we modeled the influence of baseline alcohol consumption, disinhibition and harm avoidance (ages 15, 18 and 21 years) on drinking motives and motives not to drink three years later (ages 18, 21 and 24 years) and alcohol use and drinking-related problems seven years subsequently (ages 25, 28, 31 years).

Results

Path analytic models were relatively invariant across cohort. Across cohorts, disinhibition and baseline alcohol consumption related to later positive reinforcement drinking motives, but less consistency was found for the prediction of negative reinforcement motives to drink. While positive reinforcement motives were associated with greater alcohol consumption and problems seven years later, negative reinforcement motives were generally associated with problems alone. Positive reinforcement motives for drinking mediated relations between baseline consumption and later consumption. However, results were mixed when considering disinhibition as a predictor and drinking problems as an outcome. Similarly, personality and baseline consumption related to later motives not to drink and such motives predicted subsequent alcohol-related problems. However, mediation was not generally supported for pathways through motives to abstain.

Conclusions

The results of this study replicate and extend previous longitudinal findings with youth and add to the growing literature on motivations not to engage in alcohol use.

Keywords: Motives not to drink, drinking motives, alcohol use and problems, young adults

Introduction

By the end of high school, nearly three quarters of adolescents (70%) have consumed alcohol, and about two fifths (33%) have done so by eighth grade (Johnston et al., 2011). In 2010, more than half (51%) of 12th graders and approximately 15% of 8th graders report having been drunk at least once in their life (Johnston et al., 2011). Given the increased risk for harm associated with heavy alcohol consumption in youth (Committee on Substance Abuse, 2010), further research into processes underlying adolescents' decisions to drink or not to drink is needed.

The pathways to alcohol-related problems are multifaceted and multiply determined (Brown et al., 2011). Cox and Klinger's (1988) motivational model of alcohol use proposed that alcohol use is determined by the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and contextual factors, and that these factors take effect through a final, common motivational pathway to alcohol use or abstention. They posited that drinking motives stem from expectations of affective change, or whether a person believes that alcohol use will increase positive affect (positive reinforcement) or decrease negative affect (negative reinforcement). These drinking motive distinctions highlight the varying influence of internal psychological factors and external social pressures on alcohol consumption decisions.

Cooper (1994) expanded this area by developing a four factor measure of drinking motivations, well validated in both adolescent and young adult samples (e.g., Carey and Correia, 1997; Cooper et al., 1995; MacLean and Lecci, 2000; Martens et al., 2008). Adolescents most susceptible to problematic drinking are those who drink in order to regulate negative emotions, that is, who use alcohol as a method of coping (Cooper, 1994). Overall, social motives are associated with moderate and heavy alcohol use, enhancement motives with heavy drinking, and coping motives with alcohol-related problems both prospectively (Shelleman-Offermans et al., 2011) and at a single point in time (Kuntsche et al., 2005; Mezquita et al., 2010)

Although considerable research has focused on drinking motives from adolescence through early adulthood, fewer investigations have evaluated the predictive utility of the complimentary construct of motives not to drink, or reasons endorsed for abstaining from alcohol use or limiting drinking, across the same developmental age span (Epler et al., 2009). Multiple domains of motives not to drink have been proposed: personal and social motives; upbringing, religious or moral concerns; need for self-control and performance goals; past problems; and risk of harm (Greenfield et al., 1989; Huang et al., 2011). Abstinence motives are associated with decreased rates of drinking in many cross-sectional investigations of adolescents (Anderson et al., 2011; Stritzke and Butt, 2001) and college students (Greenfield et al., 1989; Huang et al., 2011). However, not all motives to abstain or limit drinking are associated with reduced consumption and problems; Epler et al. (2009), in a longitudinal investigation of college students, suggest that motives associated with fear of adverse consequences and reasons to limit drinking based on loss of control are more likely indicators of problematic consumption rather than predictors of future drinking. For late adolescents moving into adulthood, transitions in drinking patterns relate to motives to use or abstain from alcohol use (Epler et al., 2009; Epler and Sher, 2011).

Drinking and abstention motives affect alcohol-related outcomes in concert with many other individual difference and environmental variables (Cox and Klinger, 1988). As certain personality traits may place people at risk for excessive drinking (Cox et al., 2001; Sher et al., 1999), personality's relation to alcohol motivations has generated substantial research interest. In their review of studies with youth aged 10 –25 years, Kuntsche et al. (2006) found consistent support for the association of extraversion and sensation-seeking with enhancement motives and of neuroticism and anxiety with coping motives. In terms of motives to limit drinking or abstain, college students high in neuroticism were more likely to endorse motives not to drink based on upbringing and fear of negative consequences, while those high in novelty seeking endorsed fewer motives associated with fear of negative consequences (Epler and Sher, 2011).

An open question is whether both types of motivations mediate the relationship between personality factors and alcohol use and abuse patterns. Drinking motives mediate relations between impulsivity, including facets such as sensation-seeking and urgency, and alcohol use in cross-sectional investigations (Adams et al., 2012; Cooper et al., 1995; Curcio and George, 2011). However, findings from prospective studies have been mixed. In a longitudinal investigation of college students, Littlefield et al. (2010) found that changes in coping motives mediated the relationship between changes in neuroticism and impulsivity and alcohol problems from ages 18 to 35 years. In contrast, Read and colleagues (2003) did not support mediation of drinking motives on the relationship between impulsive sensation-seeking and alcohol use or problems in college students across one year, despite supporting pathways between sensation-seeking, enhancement motives, and alcohol use cross-sectionally.

The goal of this investigation was to examine the role of personality, in terms of disinhibition and harm avoidance, and motivations in predicting alcohol consumption and problems across adolescence and early adulthood. While the preponderance of past research has focused on traits associated with disinhibition, the influence of harm avoidance has been understudied in relation to alcohol motivations. Based on our review above, we hypothesized that greater disinhibition would predict increased positive reinforcement drinking motives and fewer motives to reduce consumption based on religion, upbringing, or personal convictions (i.e., beliefs). We also anticipated that harm avoidance would influence later motivations to drink as a function of negative reinforcement as well as abstention motives based on fear of loss of control, fear of adverse consequences, and personal convictions. Positive and negative reinforcement motives were expected to predict greater alcohol consumption with negative reinforcement motives predicting problems but not the amount consumed. Motives to abstain based on personal convictions should relate to less alcohol consumption and problems later, with motives relating to adverse consequences and loss of control predicting greater alcohol consumption and problems. Given the lack of uniform findings longitudinally for drinking motives as well as the limited data available on the role of motives to abstain in the literature, mediational analyses were exploratory. While we expected some cohort differences as a function of development, we did not have specific hypotheses as to the nature of differences between age groups.

This study expands previous research by combining reasons to drink and not to drink in the same analysis, by examining mediational pathways from both disinhibition and harm avoidance, by using longitudinal data which covers adolescence, emerging adulthood, and young adulthood, by using a community rather than college sample, and by focusing on both use and problems as outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Data used in this study were collected for the Rutgers Health and Human Development Project (HHDP), a five-wave, prospective longitudinal study examining the emergence and development of adolescent substance use behavior (For a more extensive overview of the study's recruitment, sample, and design see White, 1987). The HHDP study interviewed three age cohorts of adolescents (12, 15, and 18 year olds at baseline). Eligibility requirements enforced were birth year, not having a language barrier or a serious physical or mental impairment, and not living in an institution (alcohol treatment or otherwise) at the time of initial contact. Participants completed baseline assessments (1979–1981) and were subsequently re-interviewed at three more time points over the course of the project: at wave 2 (1982–1984), wave 3 (1985–1987), and wave 4 (1992–1994). The youngest cohort returned one more time at wave 5 (1999–2000). The current study includes all three age cohorts (N=1380) from waves 2 through 4: the youngest at ages 15, 18, and 25 (n=447); the middle at ages 18, 21, and 28 (n=475); and the oldest at ages 21, 24, and 31 (n=458). Approximately half of the sample was women (49.4%) and most were white (90%).

Procedures

The university Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. All parents completed informed consent forms for youth under 18, and youth under age 18 provided assent. After age 18, youth provided written consent. The typical participant spent four hours on assessments over a single day at waves 2 – 4, completing self-report questionnaires, interviews, and physical health assessments. More than 90% of the original participants returned at waves 2 – 4.

Measures

Alcohol use

Participants were asked their frequency of alcohol (beer, wine, and distilled spirits) consumption during the past year. We computed a quantity x frequency index by multiplying the maximum frequency across the three beverage types (rated on a 10-point scale from never to more than once a day) by the maximum typical quantity (across beverages on a10-point scale) of alcohol consumed on a typical occasion in the last year. At baseline (wave 2), the quantity/frequency index ranged from 0–90 (m= 23.81; sd= 18.97) and at wave 4 from 0–90 with a mean of 22.51 (sd=16.03). Cohorts differed on their alcohol consumption at baseline, F(2, 1305) = 124.73, p<.001, with the 15 year olds having lower levels of use than both 18 and 21 year olds, and 18 year olds having lower consumption than 21 year olds. Age groups' alcohol consumption also differed at wave 4, F(2, 1253) = 3.88, p=.02, but the pattern shifted; 25 year olds evidenced significantly higher levels of use than the 31 year olds, but not the 28 year olds. Given non-normality, these variables were square root transformed prior to analysis.

Alcohol-related problems

A shortened version of the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White and Labouvie, 1989; 2000) assessed the frequency of experiencing 18 negative consequences (e.g., neglected responsibilities, withdrawal symptoms) while drinking or because of drinking over the last three years. Answers ranged from “never” to “more than five times” on a scale of 0–3. RAPI scores ranged from 0–51 in this sample (m=2.91, sd=6.32). Cohorts did not differ significantly on this scale (α = .91). Given non-normality, we used a square root transformation of RAPI scores prior to analysis.

Motives to drink or abstain

All participants were administered items relating to motives to drink alcohol or abstain at wave 3. Nonusers (lifetime abstainers and stoppers) were asked to rate the importance of 50 motives why someone might drink and users were asked to rate the importance of these same motives for their drinking (Labouvie and Bates, 2002). Items were rated on a 1 (Not very important) to 3 (Very important) scale. Using content analysis, items were assigned to match domains of drinking motives, social, enhancement, coping and conformity, as depicted in the Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (Cooper, 1994). Unfortunately, items corresponding to the social, enhancement and conformity motives insufficiently covered the content domains of interest and evidenced low internal consistency (alphas below .70). As such, we opted to create two scales, positive reinforcement reasons for drinking (social/enhancement; α = .76) and negative reinforcement reasons (coping/conformity; α =.84), a strategy similar to that described in Carey and Correia (1997).

Both nonusers and users also reported on the relative influence of 45 motives not to drink on the same scale. Items ranged from a lack of desire to concerns about negative consequences. Using Epler and colleagues' (2009) operationalization of motives to abstain or limit drinking, we generated scales capturing loss of control (i.e., reason attributed to getting into trouble or losing control; α = .84), adverse consequences (i.e., interference with responsibilities; α = .84) and convictions (i.e., religion, upbringing, or views of others; α = .83).

Personality

HHDP participants were administered the Personality Research Factor, Form-E Harm Avoidance Scale (PRF; Jackson, 1974). The harm avoidance scale included items such as, “I like to live dangerously” (reverse coded), and “I don't ever go walking in places where there might be poisonous snakes.” A random selection of 12 of the original 16 dichotomous items were included due to time constraints; shortened scales were comparable psychometrically to the full scales in other investigations (Bates and Labouvie, 1997; Labouvie and McGee, 1986) and the harm avoidance scale has been shown to have high reliability (α = .94; White et al., 2001). Scores ranged from 0–12 with a mean of 5.35 (sd=.07). At age 15, the youngest cohort endorsed greater harm avoidance (m = 7.22, sd = 2.76) than the middle (age 18: m = 6.44, sd = 2.97) and oldest cohorts (age 21: m = 6.17, sd = 3.14), F(2, 1320) = 14.67, p<.0001.

Impulsivity was measured using the disinhibition (DIS) subscale from Zuckerman's Sensation-Seeking Scale (Zuckerman, 1979). DIS scores assessed social sensation seeking through drinking, sex, and parties (α = .66). Scores ranged from 0–8 within this sample with a mean of 3.82 (sd=2.12) and varied significantly by cohort, F(2, 1293) = 3.51, p=.03, with the youngest cohort having higher scores than the middle.

Analytic Plan

Initial examination of the data, using mixed-effects models in Stata 12.0 (Stata Corp, 2011), indicated a significant random effect for cohort, suggesting that model parameters were influenced by cohort membership. As such, we chose to present models for each cohort separately and systematically compared relations among groups.

We conducted path analyses to examine prospective relations among baseline drinking and personality at wave 2, motives at wave 3, and outcomes at wave 4 separately by cohort. Invariance testing evaluated the level of consistency of models across cohorts by constraining pathways sequentially to equivalence across models and evaluating change using chi square difference testing (Mplus 6.1; Muthen and Muthen, 2010). Given the number of pathways evaluated, a p <.01 level was used to determine substantive change when comparing models (Ullman, 2001). Using multivariate delta standard errors as outlined by MacKinnon and colleagues (2002), indirect paths from personality to outcomes through motives were estimated in MPlus. Missing data within these models (at least one variable missing: 12% [cohort 1] – 21% [cohort 3]) was handled using full information maximum likelihood.

Results

Associations between motives to drink and not to drink across cohorts are provided in Table 1. Correlations suggest that motives to drink and not to drink were generally independent of one another. A notable exception was the moderate inverse relation between positive reinforcement motives and motives not to drink based on personal convictions. Motives within type (drink or abstain) were highly correlated (Table 1).

Table 1.

Bivariate associations between motives types across cohorts (N=1380).

| Variables | Pos Re | Neg Re | Control | Conseq |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neg Re | .71 | |||

| Control | −.04 | .06 | ||

| Conseq | −.03 | .03 | .72 | |

| Convict | −.12 | −.04 | .67 | .66 |

Note: Pos Re: Pos reinforcement drinking motives; Neg Re: Negative reinforcement drinking motives; Control: Loss of control abstinence motives; Conseq: Adverse consequences abstinence motives; Convict: Convictions abstinence motives; Bold correlations significant at p<.001.

Mediation through Drinking Motives

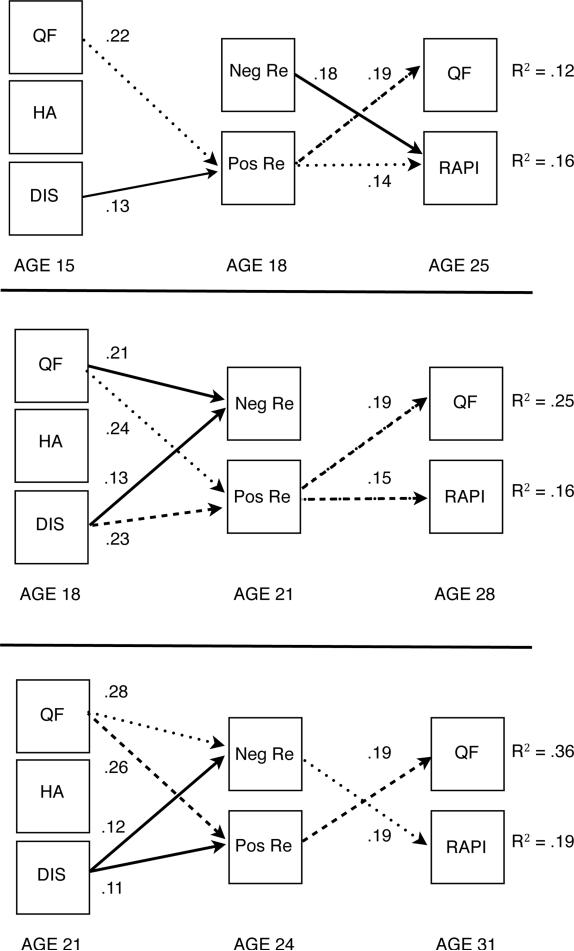

Figure 1 depicts the path analytic results by cohort for drinking motives. The overall model accounted for a statistically significant proportion of the variance in both drinking behavior (R2 = .12 –.36, ps < .0001) and drinking-related problems (R2 = .16 –.19, ps < .0001). A number of direct effects emerged across cohorts, both within and outside of mediated pathways (Figure 1; Table 2). In terms of relations between predictors and outcomes, drinking at baseline predicted alcohol consumption and RAPI scores across cohorts. However, results were mixed for relations between personality and alcohol-related outcomes. Disinhibition was associated with later drinking for the two younger cohorts, but not the oldest, with disinhibition's only relation to drinking problems in the middle cohort. Harm avoidance at age 15 predicted less drinking and fewer problems at age 25 but was not statistically significant in the other cohorts when considering dishinhibition and baseline consumption contemporaneously.

Figure 1.

Path analytic results for drinking motives model by cohort. The direct pathways between personality and outcomes and associations between variables at the same time point were modeled are presented in Table 2. Pos Re: Positive reinforcement drinking motives; Neg Re: Negative reinforcement drinking motives; All included pathways were significant at p <.05

Table 2.

Model estimates for predictor-outcome relations and concurrent associations excluded from Figure 1, presented by cohort.

| Estimates | Cohort 1 (ages 15–25) | Cohort 2 (ages 18–28) | Cohort 3 (ages 21–31) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects: | |||

| Wave 2 – Wave 4 | |||

| QF2→ QF4 | .13 (.09) | .37 (.32) | .55 (.52) |

| HA → QF4 | −.09 (−.10) | −.02 (−.01) | −.03 (−.03) |

| DIS → QF4 | .13 (.10) | .15 (.11) | .05 (.04) |

| QF2 → RAPI | .11 (.07) | .27 (.21) | .32 (.24) |

| HA → RAPI | −.17 (−.17) | −.01 (−.01) | −.01 (−.00) |

| DIS → RAPI | .09 (.06) | .10 (.05) | .02 (−.01) |

| Covariances | |||

| DIS - HA | −.28 | −.29 | −.28 |

| DIS - QF2 | .51 | .48 | .48 |

| HA - QF2 | −.17 | −.36 | −.27 |

| Pos Re – Neg Re | .70 | .65 | .74 |

| QF - RAPI | .33 | .51 | .47 |

Note: DIS: disinhibition; HA: harm avoidance; Pos Re: positive reinforcement drinking motives; Neg Re: negative reinforcement drinking motives; Control: loss of control abstinence motives; Conseq: adverse consequences abstinence motives; Convict: convictions abstinence motives; QF: quantity/frequency of drinking; RAPI: drinking-related problems; Betas are reported for all estimates; Estimates in () indicate parameter estimates with mediators within the model. Bold indicates p < .05.

For the effects of initial predictors on the proposed mediators, greater disinhibition and baseline alcohol consumption consistently predicted increased endorsement of positive reinforcement motives. For the older two cohorts, increased disinhibition also related to greater negative reinforcement motivations. Contrary to expectations, harm avoidance did not predict drinking motives when considered in concert with disinhibition and baseline alcohol consumption. Associations between putative mediators and outcomes suggested that positive reinforcement motives predicted increased alcohol consumption seven years later across cohort, but only predicted RAPI scores for two younger cohorts. Increased negative reinforcement motives were associated with greater alcohol-related problems for the youngest and oldest cohorts when accounting for baseline characteristics.

Indirect tests indicated that drinking motives mediated relations between quantity/frequency of alcohol consumption over time across cohorts (Table 2). Higher levels of alcohol consumption were associated with increased positive reinforcement motives three years later that predicted increased alcohol consumption seven years subsequently. Interestingly, results suggest that positive reinforcement motives fully mediated these relations in the youngest cohort, z = 2.35, p = .02, but evidenced partial mediation in the two older cohorts, zs = 2.54 – 2.66, ps < .01. The pathway from baseline drinking to RAPI scores was mediated through positive reinforcement motives for the younger cohorts, with the youngest cohort evidencing full mediation, z = 1.95, p =.05, and partial mediation for the next oldest cohort, z = 2.14, p = .03. We also found partial mediation for the disinhibition-positive reinforcement-drinking pathway in the middle cohort, z = 2.60, p = .009. The sole mediation effect for negative reinforcement motives was found within the oldest cohort, z = 2.38, p =.02; higher levels of drinking at age 21 predicted negative reinforcement motives at age 24, and subsequently, increased alcohol-related problems at age 31.

Despite these differences, there was limited variation in prediction across cohort in this model (fully constrained model: χ2(43) = 140.84, p < .001, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .07 (CI: .06–.08)). Invariance testing indicated that leaving associations between baseline and follow-up alcohol consumption, between baseline drinking and negative reinforcement motives, and between harm avoidance and baseline drinking unconstrained across cohorts improved model fit. This final model evidenced an excellent fit to the data, χ2(37) = 50.85, p = .06, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .03 (CI: .00 – .05).

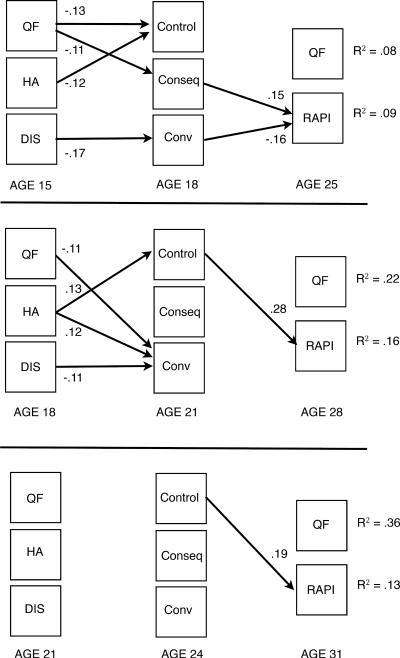

Mediation through Motives to Abstain

Overall, the abstinence motives model accounted for a statistically significant proportion of the variance in both drinking behavior (R2 = .08 –.36, ps ≤ .002) and drinking-related problems (R2 = .09 –.16, ps ≤ .001; Figure 2). As the magnitude and direction of predictor-outcome relations were described above, we will not reiterate them here. Direct effects suggested that baseline characteristics influenced motives to abstain three years later for the two younger cohorts (Table 3). As hypothesized, greater disinhibition predicted fewer motives not to drink based on convictions. Higher baseline alcohol consumption was inversely related to reasons based upon loss of control and adverse consequence motives in the youngest cohort and predicted fewer motives related to convictions for the middle cohort. Consistent with expectations, harm avoidance predated increased motivations to abstain based on loss of control and convictions from age 21 to age 28, but only within the middle cohort. Interestingly, and contrary to hypotheses, harm avoidance was associated with fewer fear of loss of control motives for participants transitioning from age 15 to age 18.

Figure 2.

Path analytic results for abstinence motives model by cohort. The direct pathways between personality and outcomes and associations between variables at the same time point are presented in Table 3. Control: Loss of control abstinence motives; Conseq: Adverse consequences abstinence motives; Convict: Convictions abstinence motives. All included pathways were significant at p <.05.

Table 3.

Model estimates for predictor-outcome relations and concurrent associations excluded from Figure 2, presented by cohort.

| Estimates | Cohort 1 (ages 15–25) | Cohort 2 (ages 18–28) | Cohort 3 (ages 21–31) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effects: | |||

| Wave 2 – Wave 4 | |||

| QF2→ QF4 | .13 (.12) | .37 (.37) | .55 (.55) |

| HA → QF4 | −.09 (−.10) | −.02 (−.01) | −.03 (−.02) |

| DIS → QF4 | .13 (.11) | .15 (.16) | .05 (.05) |

| QF2 → RAPI | .11 (.11) | .27 (.29) | .32 (.33) |

| HA → RAPI | −.17 (−.17) | −.01 (−.04) | −.01 (.00) |

| DIS → RAPI | .09 (.07) | .10 (.11) | .02 (.02) |

| Covariances | |||

| DIS - HA | −.27 | −.30 | −.28 |

| DIS - QF2 | .51 | .48 | .48 |

| HA - QF2 | −.17 | −.36 | −.27 |

| Control-Conseq | .72 | .70 | .74 |

| Control-Convict | .66 | .61 | .69 |

| Conseq-Convict | .69 | .61 | .66 |

| QF - RAPI | .36 | .55 | .49 |

Note: DIS: disinhibition; HA: harm avoidance; Control: loss of control abstinence motives; Conseq: adverse consequences abstinence motives; Convict: convictions abstinence motives; QF2: quantity/frequency of drinking at baseline (wave 2); QF4: quantity/frequency of drinking at wave 4; RAPI: drinking-related problems; Betas are reported for all estimates; Estimates in () indicate parameter estimates with mediators within the model. Bold indicates p < .05.

When predicting alcohol-related problems as a function of motives not to drink, while accounting for baseline characteristics, a diverse set of findings emerged. For 21 and 24 year olds, greater endorsement of fear of loss of control motives predicted higher RAPI scores seven years later per our hypothesis. Within the youngest cohort, fear of adverse consequences predicted higher RAPI scores, while greater motivation to abstain based upon personal convictions led to fewer alcohol-related problems as anticipated. Motives to abstain did not predict later alcohol consumption above and beyond baseline predictors.

A single mediated effect was found for motives to abstain. In the middle cohort, greater harm avoidance at age 18 was related to greater concerns relating to loss of control at age 21, leading to increased alcohol-related problems as age 28, z = 2.12, p = .04.

Invariance testing again suggested limited variability across cohorts (fully constrained model: χ2(60) = 178.48, p < .001, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .07 (CI: .06–.08)). Leaving associations between baseline and follow up alcohol consumption, between loss of control motives and RAPI, and between harm avoidance and baseline drinking unconstrained improved model fit. This final model evidenced an excellent fit to the data, χ2(52) = 82.64, p = .004, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .04 (CI: .02 – .05).

Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to examine longitudinal relations between personality, alcohol motivations, and alcohol consumption and related problems across the developmental period from adolescence to young adulthood. Using an accelerated cohort longitudinal design, we had an unique opportunity to examine how relations between traits and cognitions may be stable or change when considered from middle adolescence to emerging adulthood, across emerging adulthood, and from emerging adulthood into young adulthood. Our results add to the diversity of findings from longitudinal studies examining pathways from personality to drinking motives to alcohol use and problems.

Baseline drinking, more so than disinhibition or harm avoidance, predicted later drinking motives and subsequent alcohol use and problems. Similar to Read et al. (2003), we found robust effects from baseline alcohol consumption to later use and problems. Interestingly, the magnitude of the association between previous alcohol consumption and later drinking grew linearly with age. For those evaluated from ages 21 to 31, three quarters of the final effect on alcohol consumption was accounted for by baseline drinking, while only 6% of drinking at age 25 was predicted by alcohol use at age 15. These findings suggest that the influence of personality and motives relating to alcohol use may have the greatest impact on consumption across adolescence and emerging adulthood but may be less influential as drinking patterns stabilize.

Not withstanding these differences, our models were relatively invariant across age cohort, making it difficult to make blanket statements about the role of development from these findings. Notably, one pathway to differ as a function of age was the relation between baseline alcohol consumption and negative reinforcement motives. For older youth, transitioning from age 18 to 21 and age 21 to 24, alcohol consumption predicted increased negative reinforcement motives. This supports the notion that drinking to relieve negative affect is more common as individuals age and garner greater experience with drinking, but is inconsistent with other work showing similar effects in adolescence (Kuntsche et al., 2005). Alternatively, it is possible that negative reinforcement motives' effects in adolescence were masked by the substantial overlap in our measures of drinking motives.

While we found limited support for mediation, personality did relate to motives across time. Disinhibition predicted motives relating to positive reinforcement from drinking across age cohorts, consistent with the body of previous research using cross-sectional and longitudinal designs (Kuntsche et al., 2006). Unsurprisingly, disinhibition was inversely related to abstinence motives relating to personal convictions, consistent findings from Epler and Sher (2011). Harm avoidance had no influence on motives to drink when considered in tandem with other factors at baseline. This divergence from other findings within the literature may be attributed to the use of harm avoidance versus neuroticism, which is commonly used in other investigations (Littlefield et al., 2010; Kuntsche et al., 2005). Harm avoidance from the PRF has been associated with low openness to experience and facets of neuroticism, including high anxiety but decreased warmth (Costa and McCrae, 1988), less theoretically consistent with notions of negative emotionality driving use of alcohol as a negative reinforcer.

In addition to our use of harm avoidance as a predictor, we also used a somewhat different conceptualization of drinking motives here. While we attempted to cover the content domains of Cooper's (1994) four-factor model of drinking motives, we were unable to do so adequately with our available items. We chose to focus on the positive vs. negative reinforcement dimensions of these constructs, integrating social-enhancement motives and coping-conformity motives. While a number of authors have integrated these factors along these lines, or argued for such integration, based upon their findings (e.g., Carey and Correia,1997; Read et al., 2003), this difference could have influenced our findings, especially considering the focus on enhancement and coping motives when taking into account relations between personality and motivations (Kuntsche et al., 2006; Littlefield et al., 2010).

This investigation was one of the first to consider relations between personality, motives not to drink, and alcohol-related outcomes longitudinally. Most notably, abstinence motives relating to loss of control predicted increased alcohol-related problems later and differed significantly between the two older cohorts and the youngest, where no such relation emerged. It may be that fears relating to loss of control are less salient at 18 than at 21 or 24, and therefore less influential downstream. First, as youth age and begin to adopt adult responsibilities, they may evidence greater concerns about loss of control (Labouvie, 1996). Alternatively, drinking history might be a factor in this finding. As heavy drinkers have greater experience with drinking, these individuals may have already lost control and experienced negative consequences, and thus are concerned about those reasons for not drinking. Given that our investigation included individuals who abstain, use, and have stopped use, those who have stopped drinking as a result of negative outcomes from drinking may have driven the effects of loss of control on negative consequences. More intricate analyses examining associations between motives and consequences for drinkers and stoppers over time would shed light on this issue.

The strengths of this investigation reside in its use of an accelerated cohort longitudinal design in evaluating these constructs in a large sample of youth recruited from the community. The instruments used demonstrated sound psychometric properties and reflected the state-of-the-art at the time of data collection. As similar assessments of drinking motives and motives for abstinence across users and nonusers, as well as some personality measures, were not available at all time points, we could not model change in these constructs over time nor their influence at each wave. Caution should be exercised in generalizing these findings to more recent cohorts, given the time period of data collection and also to more ethnically and racially diverse samples.

This work contributes to a body of research examining how traits and cognitions interact in the prediction of risk behavior in youth (Cox and Klinger, 2011; Cyders et al., 2007; Smith and Anderson, 2001). Work by Conrod and colleagues have applied these notions to the development of targeted selective intervention programs geared toward youth drinking (Conrod et al., 2008; Conrod et al., 2010). By identifying youth with tendencies towards disinhibition, interventionists can tailor the cognitive intervention towards those motives that are seen as the more proximal predictors of problematic behaviors. Our findings, to some extent, add to the body of empirical support for these types of selective intervention programs in adolescence and emerging adulthood. In addition, our findings add to the body of literature using current alcohol use as an indicator of the need for intervention.

Future research into the interplay of personality and cognition in predicting adolescent and emerging adult alcohol consumption and problems would benefit from inclusion of both expectancies and motives, with a broader array of personality traits, in these models. As found in previous work, alcohol expectancies for use and abstention may demonstrate differential relations to behavior, in conjunction with motives to drink or abstain, for youth at transition points in their use of alcohol (e.g., initiation, escalation, or cessation; Bekman et al., 2011). As integrative models of motives to use or abstain have shown promise for understanding alcohol use, research that investigates the interplay of these constructs for other substances of abuse, particularly tobacco and marijuana, would further our understanding of the similarities and differences in the underlying processes promoting or inhibiting alcohol and other drug engagement for youth.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported, in part, by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA/AA 03395 to Pandina, Labouvie, and White) and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA 019511 to Mun and White). Many thanks to Ken Sher, Ph.D. for his statistical consultation.

References

- Adams ZW, Kaiser AJ, Lynam DR, Charnigo RJ, Milich R. Drinking motives as mediators of the impulsivity-substance use relation: pathways for negative urgency, lack of premeditation, and sensation seeking. Addic Behav. 2012;37:848–855. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KG, Grunwald I, Bekman N, Brown SA, Grant A. To drink or not to drink: motives and expectancies for use and nonuse in adolescence. Addict Behav. 2011;36:972–979. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates ME, Labouvie EW. Adolescent risk factors and the prediction of persistent alcohol and drug use into adulthood. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:944–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekman NM, Anderson KG, Trim RS, Metrik J, Diulio AR, Myers MG, Brown SA. Thinking and drinking: alcohol-related cognitions across stages of adolescent alcohol involvement. Psychol Addict Beh. 2011;25:415–425. doi: 10.1037/a0023302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, Ramo DE, Anderson KG. Long-term trajectories of adolescent recovery. In: Kelly J, White W, editors. Addiction recovery management: theory, research and practice. Humana Press; Totowa: 2011. pp. 127–142. [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Correia CJ. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. J Stud Alc. 1997;58:100–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Substance Abuse Alcohol use by youth and adolescents: a pediatric concern. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1078–1087. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Mackie C, Castellanos N. Personality-targeted interventions delay the adolescent onset of drinking and binge drinking. J Child Psychol Psych. 2008;49:181–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod PJ, Castellanos-Ryan N, Strang J. Brief, personality-targeted coping skills interventions prolong survival as a non-drug user over a two-year period during adolescence. Arch Gen Psych. 2010;67:85–93. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychol Assess. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: a motivational model of alcohol use. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. From catalog to classification: Murray's needs and the Five-Factor Model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;55:256–265. [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. J Abn Psychol. 1988;97(2):168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox W, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use: determinants of use and change. In: Cox WM, Klinger E, editors. Handbook of motivational counseling: Goal-based approaches to assessment and intervention with addiction and other problems. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. pp. 131–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Yeates GN, Gilligan PT, Hosier SG. Individual differences. In: Heather N, Peters TJ, Stockwell T, editors. International handbook of alcohol dependence and problems. John Wiley and Sons; New York: 2001. pp. 357–374. [Google Scholar]

- Curcio AL, George AM. Selected impulsivity facets with alcohol use/problems: the mediating role of drinking motives. Addic Behav. 2011;36:959–964. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyders MA, Smith GT, Spillane NS, Fischer S, Annus AM, Peterson C. Integration of impulsivity and positive mood to predict risky behavior: development and validation of a measure of positive urgency. Psychol Assess. 2007;19:107–118. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epler AJ, Sher KJ, Piasecki TM. Reasons for abstaining or limiting drinking: a developmental perspective. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23:428–442. doi: 10.1037/a0015879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epler AJ, Sher KJ. Reasons for abstaining or limiting drinking: predictors and relations with alcohol involvement in a longitudinal college sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2011;35:275a. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield TK, Guydish J, Temple MT. Reasons students give for limiting drinking: a factor analysis with implications for research and practice. J Stud Alc. 1989;50:108–115. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JH, DeJong W, Schneider SK, Towvin LG. Endorsed reasons for not drinking alcohol: a comparison of college student drinkers and abstainers. J Behav Med. 2011;34:64–73. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DN. Personality Research Form Manual. Research Psychologists Press; Goshen: 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2010: Vol. I, Secondary school students (No. 09-7402) National Institute on Drug Abuse; Bathesda: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality, and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addict Behav. 2006;31:1844–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie E. Maturing out of substance use: Selection and self-correction. J Drug Issues. 1996;26:457–476. [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie EW, Bates ME. Reasons for alcohol use in young adulthood: validation of a three-dimensional measure. J Stud Alc. 2002;63:145–155. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labouvie EW, McGee CR. Relation of personality to alcohol and drug use in adolescence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:289–293. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Do changes in drinking motives mediate the relation between personality change and “maturing out” of problem drinking? J Abn Psychol. 2010;119:93–105. doi: 10.1037/a0017512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Meth. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean MG, Lecci L. A comparison of models of drinking motives in a university sample. Psychol Addict Beh. 2000;14:83–87. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Rocha TL, Martin JL, Serrao HF. Drinking motives and college students: further examination of a four-factor model. J Counsel Psychol. 2008;55:289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Mezquita L, Stewart SH, Ruipérez M. Big-five personality domains predict internal drinking motives in young adults. Pers Ind Diff. 2010;49:240–245. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LM, Muthen BO. Mplus User's Guide. 6th ed. Muthen and Muthen; Los Angeles: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Kahler CW, Maddock JE, Palfai TP. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17:13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schelleman-Offermans K, Kuntsche E, Knibbe RA. Associations between drinking motives and changes in adolescents' alcohol consumption: a full cross-lagged panel study. Addiction. 2011;106:1270–1278. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Trull TJ, Bartholow BD, Vieth A. Personality and alcoholism: Issues, methods, and etiological processes. In: Leonard KE, Blane HT, editors. The Guilford Press substance abuse series. Guilford; New York: 1999. pp. 54–105. [Google Scholar]

- Smith GT, Anderson KG. Personality and learning factors combine to create risk for adolescent problem drinking: a model and suggestions for intervention. In: Monti PM, Colby SM, O'Leary TA, editors. Adolescents, alcohol, and substance abuse: Reaching teens through brief interventions. Guilford; New York: 2001. pp. 109–141. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. StataCorp LP; College Station: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Stritzke WGK, Butt JCM. Motives for not drinking alcohol among Australian adolescents: developmental and initial validation of a five-factor scale. Addict Behav. 2001;26:633–649. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman J. Structural Equation Modeling. In: Tabachnick B, Fidell L, editors. Using Multivariate Statistics. Allyn and Bacon; Boston: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- White HR. Longitudinal stability and dimensional structure of problem drinking in adolescence. J Stud Alc. 1987;48:541–550. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1987.48.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Bates ME, Buyske S. Adolescence-limited versus persistent delinquency: extending Moffitt's hypothesis into adulthood. J Abn Psychol. 2001;110:600–609. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. J Stud Alc. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Longitudinal trends in problem drinking as measured by the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index. Alc Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:76a. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Sensation seeking: Beyond the optimal level of arousal. Erlbaum; Hillsdale: 1979. [Google Scholar]