Abstract

Acinetobacter baumannii is a Gram-negative pathogen responsible for severe nocosomial infections by forming biofilms in healthcare environments. The two-domain response regulator BfmR has been shown to be the master controller for biofilm formation. Inactivation of BfmR resulted in an abolition of pili production and consequently biofilm creation. Here we report backbone and sidechain resonance assignments and secondary structure prediction for the C-terminal domain of BfmR (residues 130–238) from A. baumannii.

Biological Context

Acinetobacter baumannii is a Gram-negative pathogen with the ability to cause serious nocosomial infections in immunocompromised patients (Mussi et al. 2010). A. baumannii infections are often acquired in healthcare environments primarily from the bacteria forming biofilms on hospital surfaces and medical care devices (Fux et al. 2005; Vidal et al. 1996). Biofilm formation is controlled in A. baumannii by the two-component regulatory system BfmSR and is predicated on the development of pili by the expression of the csu operon (Tomaras et al. 2008). The two-component systems consist of a membrane bound sensor kinase (BfmS) that senses environmental signals and a response regulator (BfmR) that mediates the bacterial response through targeted gene expression (Beier et al. 2006; Gaddy et al. 2009; Stephenson et al. 2002; Stock et al. 2000). It has been shown that inactivation of the response regulator BfmR resulted in an abolition of pili production and consequently biofilm creation (Tomaras et al. 2008).

Many response regulators have been examined in A. baumannii functionally but very few have been structurally characterized. Due to its critical role as the master controller for biofilm formation, BfmR is a viable therapeutic drug target (Ballard et al. 2008; Rogers et al. 2010; Tang et al. 2012). BfmR is a 27 kDa protein existing as a functional dimer consisting of two distinct domains: an N-terminal phosphorylation domain and a C-terminal DNA binding domain (Tomaras et al. 2008). The N-terminal regulatory domain (residues 1–127) is a highly conserved REC domain with a phosphorylation site at Asp58 and a hypothetical dimerization interface. The C-terminal DNA binding domain (residues 130–238) maintains an OmpR-like structure with a winged-helix folding pattern. Upon phosphorylation of the N-terminus, BfmR undergoes global conformational changes permitting DNA binding of the C-terminus allowing the expression of target genes (Stock et al. 2000). The problematic health concerns of this pathogen coupled with the link between BfmR and the development of biofilms and enhanced antibiotic resistance makes this response regulator an ideal therapeutic target. As a first step toward solving the complete structure of BfmR, we report backbone and sidechain chemical shift assignments of the C-terminal domain of the A. baumannii response regulator protein BfmR (residues 130–238).

Methods and experiments

C-terminal BfmR (residues 130–238) from A. baumannii was cloned into expression vector pET-16b (Novagen) with a C-terminal histidine tag and transformed into BL21(DE3) cells (Genesee) for expression. To uniformly label BfmRC with 13C/15N, cells were grown in 1L of M9 media supplemented with 15NH4Cl and/or 13C-glucose at 37°C. At OD600 of ~0.7 the temperature was reduced to 30°C and expression induced with 1mM IPTG. The cells were harvested by centrifugation 4 hours postinduction at 7,000g for 15 min. Cell pellets were suspended in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM imidazole, and .02% sodium azide) and sonicated with resulting cell lysate clarified by centrifugation at 15,000g and the resulting supernatant was passed over Ni-NTA agarose resin (Qiagen). Samples for NMR experiments were dialyzed into NMR buffer (25 mM Tris- HCl, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 0.02% sodium azide, in 10% and 100% D2O) at pH 6.5 and concentrated to 1 mM.

All NMR experiments were performed at 298K on a Varian Inova 600 MHz and Bruker Avance 700 MHz, both equipped with cryoprobes. Backbone chemical shifts were assigned in a sequential manner from the following experiments: 2D [15N-1H] TROSY-HSQC, HNCO, HN(CA)CO, CBCA(CO)NH, HNCACB, and a CC(CO)NH. Sidechain proton chemical shifts were assigned using the following experiments: HBHA(CO)NH, (H)CC(CO)NH, 15N-TOCSY (50 and 100 ms), and an HCCH-TOCSY. Aromatic assignments were made from a 13C-aromatic NOESY (100 ms). Data was processed using NMRPipe (Delaglio et al., 1995)and analyzed using Sparky (Goddard and Kneller 2006) and NMRView (Johnson et al. 1994) Phi/Psi dihedral angles and resulting secondary structure prediction was calculated using the program TALOS+ (Shen et al. 2009) and deviations from random coil values (Wishart et al. 1994).

Assignments and data deposition

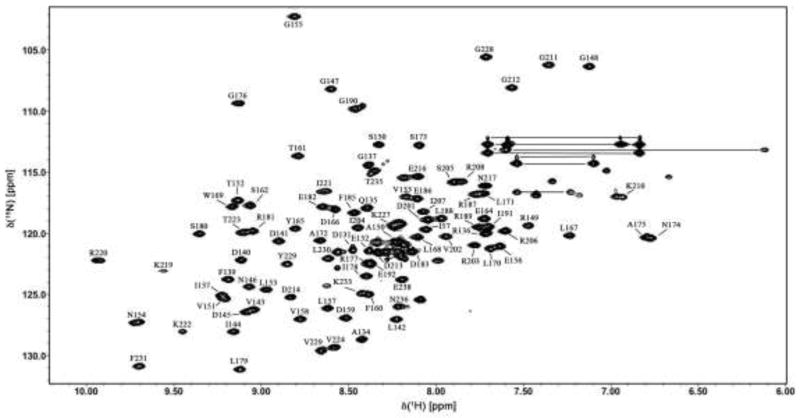

In total, 93% of all possible backbone amide assignments have been obtained with the exception of residues 193–199 and 225–226 as shown in the 2D [1H-15N] HSQC spectrum in Fig. 1. Near complete backbone resonances for Cα (93%), Cβ (92%), C′ (93%), Hα (93%) have been assigned including 91% of sidechain and 90% of aromatic proton resonances. Secondary structure prediction by the program TALOS+ and Cα chemical shift deviations indicate that C-terminal BfmR indeed conforms to an OmpR like structure as shown in Fig. 2. The missing residues 193–199 likely suffer from exchange broadening. Comparing this gap of residues to OmpR NMR structure from E. coli (38% identity and 51 % similarity, pdb code 2JPB) indicates a dynamic loop region linking helix α3 to helix α4 with a large amount of flexibility. The chemical shift assignments have been deposited in the BioMagResBank (http://www.bmrb.wisc.edu) under the accession number 18849.

Fig. 1.

2D [1H-15N] TROSY-HSQC spectrum of 750 μM C-terminal BfmR protein from Acinetobacter baumannii in 50mM KCl, 25mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, and 0.02% sodium azide at 700 MHz spectrometer

Fig. 2.

A) Chemical shift index of C-terminal BfmR as determined from TALOS+ using backbone Cα, Cβ, Hα, and C′ atoms. Prediction with areas of positive values indicating 0extended sheet regions and negative values indicating helical secondary structure. B) Difference of Cα chemical shifts from random coil values predicting secondary structure. Based on the deviations, areas of negative values indicate extended sheet regions and positive values indicate helical secondary structure.

References

- Ballard T, Richards J, Wolfe A, Melander C. Synthesis and antibiofilm activity of a second-generation reverse-amide oroidin library: A structure?activity relationship study. Chemistry A European Journal. 2008;14(34):10745–10761. doi: 10.1002/chem.200801419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier D, Gross R. Regulation of bacterial virulence by two-component systems. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2006;9(2):143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaglio F, Grzesiek S, Vuister GW, Zhu G, Pfeifer J, Bax A. NMRPipe: A multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. Springer; Netherlands: 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fux CA, Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Stoodley P. Survival strategies of infectious biofilms. Trends in Microbiology. 2005;13(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaddy JA, Actis LA. Regulation of acinetobacter baumannii biofilm formation. Future Microbiology. 2009;4(3):273–278. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BA, Blevins RA. NMR view: A computer program for the visualization and analysis of NMR data. Springer; Netherlands: 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussi MA, Gaddy JA, Cabruja M, Arivett BA, Viale AM, Rasia R, Actis LA. The opportunistic human pathogen acinetobacter baumannii senses and responds to light. Journal of Bacteriology. 2010;192(24):6336–6345. doi: 10.1128/JB.00917-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SA, Huigens RW, Cavanagh J, Melander C. Synergistic effects between conventional antibiotics and 2-aminoimidazole-derived antibiofilm agents. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2010;54(5):2112–2118. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01418-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Delaglio F, Cornilescu G, Bax A. TALOS+: A hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. Springer; Netherlands: 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson K, Hoch JA. Virulence- and antibiotic resistance-associated two-component signal transduction systems of gram-positive pathogenic bacteria as targets for antimicrobial therapy. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2002;93(2–3):293–305. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(02)00198-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock AM, Robinson VL, Goudreau PN. Two-component signal transduction. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2000;69(1):183–215. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang YT, Gao R, Havranek JJ, Groisman EA, Stock AM, Marshall GR. Inhibition of bacterial virulence: Drug-like molecules targeting the salmonella enterica PhoP response regulator. Chemical Biology & Drug Design. 2012;79(6):1007–1017. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2012.01362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaras AP, Flagler MJ, Dorsey CW, Gaddy JA, Actis LA. Characterization of a two-component regulatory system from acinetobacter baumannii that controls biofilm formation and cellular morphology. Microbiology. 2008;154(11):3398–3409. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/019471-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal R, Dominguez M, Urrutia H, Bello H, Gonzalez G, Garcia A, Zemelman R. Biofilm formation by acinetobacter baumannii. Microbios. 1996;86(346):49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart DS, Sykes BD. The 13C chemical shift index: a simple method for the identification of protein secondary structure using 13C chemical shift data. J Biomol NMR. 1994;4(2):171–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00175245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]