Abstract

The use of quality of life measures (QOL) in substance abuse treatment research is important because it may lead to a broader understanding of patients’ health status and effects of interventions. Despite the high rates of comorbid cocaine and alcohol use disorders, little is known about the QOL of this population, and even less about the impact of an efficacious behavioral treatment, contingency management (CM), on QOL. In this study, data from three clinical trials were retrospectively analyzed to examine QOL in outpatient cocaine abusers with and without alcohol dependence (AD) and the impact of CM on QOL over time as a function of AD status. Patients were randomized to standard care (n = 115) or standard care plus CM (n = 278) for 12 weeks. QOL was assessed at baseline and Months 1, 3, 6, and 9. At treatment initiation, AD patients had lower QOL total scores and they scored lower on several subscale scores than those without AD. CM treatment was associated with improvement in QOL regardless of AD status. These data suggest that CM produces benefits that go beyond substance abuse outcomes, and they support the use of QOL indices to capture information related to treatment outcomes.

Keywords: quality of life, cocaine, alcohol dependence, substance abuse treatment, contingency management

In the general population, 84% of individuals with lifetime cocaine abuse have also had an alcohol use disorder.1 In treatment-seeking cocaine-dependent individuals, approximately 60% present with lifetime alcohol dependence.2–4 Individuals with concurrent cocaine and alcohol dependence show greater behavioral, psychological, and psychiatric impairment than individuals with either disorder alone. Concurrent dependence is associated with greater severity of psychosocial problems,2, 3 other drug use,2, 5, 6 and psychosis and depression.5–7

Among patients who seek treatment for cocaine use, concomitant cocaine-alcohol use disorders can negatively impact treatment outcomes. For example, Schmitz et al.8 found that dual cocaine-alcohol dependence was associated with more frequent self-reported cocaine use and greater psychiatric symptom severity at the end of substance abuse treatment than cocaine dependence alone. In another sample of treated cocaine abusers, Carroll et al.9 also reported that patients with concurrent alcohol dependence had poorer psychiatric and substance use outcomes than those without alcohol dependence.

Treatment for cocaine dependence is designed to impact drug use, and it also tends to have effects on reducing psychiatric symptoms. Another factor increasingly considered in treatment outcomes research generally is quality of life (QOL).10 QOL assessments measure individuals’ perceptions and reactions to their physical, psychological, and social functioning.11 Some QOL instruments are relatively generic (e.g., SF-36 survey; Quality Metric, Inc.).12 Others are designed to cover specific domains of QOL and/or apply to a particular population (e.g., Brogly et al.13). In a prior study14 and the present one, we used the Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI).15, 16 The QOLI is unique in that it measures a respondent's subjective satisfaction and importance on 17 domains of life (e.g., friendship, home, love relationship), yielding a global score weighted by the extent to which each domain is important to the respondent.16, 17

There are relatively few examples of QOL research in the drug abuse compared to general health care literature.18, 19 Most QOL research conducted in substance abusing populations has examined the effects of alcohol use disorder.20, 21 In general, the few existing studies show an inverse relationship between the presence of alcohol dependence and QOL. For example, McKenna et al.22 used the SF-36 to assess the QOL of patients previously treated for alcohol, and they reported that patients diagnosed with alcohol dependence have lower QOL than those with abuse and compared to the normative population. Using the same instrument, Volk et al.23 evaluated the QOL of primary care patients with alcohol problems and also found that, relative to abusers, alcohol dependent patients have significantly poorer QOL. Scores on other QOL instruments are also lower among patients admitted to an alcohol detoxification unit 24 relative to normative values.

With respect to cocaine and QOL, fewer studies exist. In one investigation, 20 the QOL of individuals initiating an outpatient randomized clinical trial for substance abuse was assessed via SF-36. The sample, primarily dependent on cocaine or alcohol, showed more impairment than the normative US population. Lower QOL is also evident in non-clinical drug dependent samples. 25, 26 For example, in a study in crack-cocaine smokers, 25 the presence of dependence and frequency of crack cocaine consumption were negatively correlated with QOL. Further, hospitalized psychiatric patients with cocaine dependence have lower QOL (defined by Lehman's Quality of Life Interview scores) than psychiatric patients with alcohol or other drug dependences.27

Importantly, changes in QOL over time can be used to gain improved understanding of treatment outcomes. For example, abstinence is associated with improvements in QOL over time in a population of outpatient cocaine abusers14 and alcohol drinkers, 28 as well as alcohol dependent patients, 29 although some older studies found no effect of abstinence on QOL.30, 31 QOL may also predict relapse. In one study conducted with inner city residents with severe history of dependence on crack and/or heroin, baseline QOL satisfaction scores served as a predictor of remission at 1 to 2 years later.32

As suggested above and elsewhere,18, 19, 33 more widespread adoption of QOL measures in drug abuse research and treatment might serve the important role of capturing information related to patients’ functioning in addition to more commonly measured outcomes (e.g., percent of abstinent days). That is, the use of QOL measures in substance abuse treatment research may lead to a broader understanding of overall health status and treatment effects.11, 20, 21, 34

Contingency management (CM) is a treatment with demonstrated efficacy for improving substance abuse treatment outcomes.35, 36 CM is based on operant-conditioning principles in that if reinforcers are delivered contingent on objective demonstration of a target behavior, such as drug abstinence, the behavior will increase in frequency. Typically, the reinforcers are vouchers exchangeable for goods or services 35 or opportunities to win prizes of different magnitudes.37 CM interventions have demonstrated efficacy for promoting abstinence from cocaine4 and alcohol,38 as well as other substances.39–41 Only one known CM study has evaluated the impact of CM on QOL. Petry et al.14 found that CM, compared to standard care, was associated with increased QOL during the treatment period and throughout follow-up. Furthermore, durations of abstinence achieved during treatment mediated the impact of CM on changes in QOL over time. These results suggest that CM may have broad beneficial effects on patients that extend beyond abstinence outcomes and the duration of provision of external reinforcers. This is an important issue that has bearing on the generalization and extension of treatment effects, a fundamental question with respect to CM as well as other drug abuse treatments.

The earlier study,14 however, did not examine the impact of polysubstance dependence on the relationships between treatment condition and QOL. Because alcohol dependence is so prevalent in cocaine-dependent patients2–4 and is independently associated with low QOL, 20, 22–24 patients with dual cocaine and alcohol diagnoses may have poorer overall quality of life and may show differential treatment response compared to their counterparts without alcohol dependence. The purpose of this retrospective data analytical study is to evaluate QOL in a large sample of cocaine abusing outpatients with versus without comorbid alcohol dependence (AD). Specific aims are to examine (1) differences in baseline QOL in cocaine treatment outpatients with and without AD, and (2) the impact of CM versus standard care on changes in QOL over time as a function of AD status.

Method

Participants

A dataset comprised of a total of 393 participants from three randomized clinical trials42–44 was analyzed in the present study. All participants were drawn from one of four community-based treatment centers located in Connecticut and Massachusetts. The four clinics shared similar structure, implemented analogous therapeutic approaches, and provided services to populations of patients with similar characteristics. Across studies, patients were comparable on QOL scores, mean years of cocaine use, education, age, and employment and marital status (all ps >.05). Recruitment for the clinical trials occurred between 1998 and 2001,42 2001 and 2002, 43 and 2000 and 2003.44 Although possible, it is unlikely that any individual participated in more than one trial as the clinics provide services in different localities. Changes in research assistant staffing were relatively infrequent, and research assistants were unaware of any instances of repeated participation in trials.

In all three trials, patients were eligible to participate if they were 18 years of age or older, met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)45 criteria for cocaine abuse or dependence, were initiating treatment in any of the clinics, and were able to understand the procedures implemented in the study. Participants were excluded from the studies if they were suicidal, had medically uncontrolled psychotic or bipolar disorders, or were in recovery for pathological gambling. Inclusion criteria were unrestrictive to increase the generalization of the findings. All participants provided written informed consent approved by the University of Connecticut Health Center Institutional Review Board.

Across the three studies, a total of 482 patients were contacted, and 433 provided informed consent. Of those who consented, 393 were randomized to a treatment condition. A total of 115 participants were randomized to standard care (SC), and a total of 278 to CM treatment, as outlined below in the Treatment section.

Procedures

The main goal of the studies on which the present analysis is based42–44 was to assess the efficacy of CM treatments relative to SC. All three studies also had the following procedural similarities: (1) randomization to the conditions; (2) assessment measures and intervals; (3) treatment duration and intensity; and (4) follow-up intervals and overall duration. Each of the studies evaluated two CM conditions, which produced longer durations of abstinence than SC treatment. Because of the procedural, patient and outcome similarities across studies, all CM conditions were combined for the purposes of this report.

Following informed consent, participants completed a 2-hour interview in which baseline and demographic data were collected, as well as substance use diagnoses via checklists derived from the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV.46 In addition, participants also completed the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) and the Quality of Life Inventory (QOLI). The BSI is a self-report questionnaire comprised of 53-items evaluating psychological distress.47 Each item is rated in a 5-point scale, and a Global Symptom Index (GSI) is calculated from the total score, ranging from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater distress.

The QOLI16 is a questionnaire aimed at assessing respondent's satisfaction and importance in 17 domains of life (e.g., health, work, love relationship, friendship) associated with subjective well-being. In each of the 17 domains, a subscale score is obtained by multiplying the respondent's importance rating by his or her satisfaction rating. The former is based on a three-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all important) to 2 (extremely important), and the latter is based in a seven-point scale ranging from -3 (very dissatisfied) to +3 (very satisfied). The total QOLI score is calculated by averaging all subscale scores that have importance ratings greater than zero. Therefore, the QOLI total score reflects well-being in specific domains considered important from the individual respondent's perspective. This questionnaire has high test-retest reliability and correlates strongly with other well-being measures.15, 16

Patients were contacted for follow-up evaluations 1, 3, 6 and 9 months after study intake, and the QOLI was re-administered. Follow-up completion rates were 84.2%, 81.2%, 73.5% and 69.0% for the respective evaluations and did not differ by study, site, treatment condition, or AD status (ps > .05). For completion of the follow-up evaluations, participants were paid $30-35.

Treatments

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two treatments—SC or CM. In each study, one third of participants were assigned to SC and two thirds to one of two CM conditions. Below is a brief description of the SC and CM treatments. For a more complete description, the reader should refer to the primary sources.42–44

Standard Care Treatment

Standard intensive outpatient treatment in all sites and studies was comprised of group therapy sessions, AIDS education, coping and life skills training, relapse prevention, and 12-step treatment. Treatment intensity and frequency varied in accord to patients’ needs. In general, intensive care lasted 2 to 4 weeks, with group sessions ranging from 3 to 5 times per week (up to 5 hours per day). Following this phase, treatment was gradually reduced, and aftercare consisted of a single weekly group session for up to 12 months. Participants also submitted study breath and urine samples. Up to 21 samples were scheduled over a period of 3 months, and those specimens were tested for cocaine, opioids, and alcohol using an onsite testing system, OnTrakTestStick (Varian, Walnut Creek, CA), for testing cocaine and opioids, and an Intoximeter (Intoximeters, Inc., St Louis, Mo.) for assessing alcohol.

CM Treatment

The CM conditions included the same SC and sample testing as outlined above. In addition, participants received tangible reinforcers contingent upon objective demonstration of abstinence and/or completion of goal-related activities. More specifically, two classes of behaviors were reinforced depending on the study and condition: (1) submission of samples negative for cocaine, alcohol, and opioids (abstinence from all three drugs concurrently); and/or (2) completion of selected activities related to the patients’ goal areas (e.g., employment, family; see 48). In studies in which both behaviors were reinforced,42, 43 each behavior was reinforced independently such that abstinence reinforcement did not affect activity reinforcement, and vice-versa. Reinforcers consisted of opportunities to earn prizes or vouchers.

Data Analytic Procedure

Independent t-tests and χ2 tests evaluated differences in baseline characteristics between patients with and without AD. Baseline variables that differed significantly between groups were included as covariates in subsequent analyses. Initially, univariate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) examined the relationship between AD status and QOL, with the overall baseline QOL score as the dependent variable. AD status, race, and baseline BSI scores were included as independent variables, and age as a weighted variable. Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) evaluated the association between AD and the 17 QOL subscales, controlling for the same covariates as above.

A repeated measure analysis of variance examined changes in QOL total scores over time. Independent variables were AD status, race, age, baseline BSI scores, and treatment condition (CM or non-CM). The interaction between treatment condition and AD status was also included in the model to determine if patients with and without AD responded differently to the interventions. All analyses were conducted on SPSS for Windows (v.15).

Results

Baseline and demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1 for patients with (n = 208) and without AD (n = 185). Approximately 29% of individuals from each group were assigned to SC and 71% to CM, consistent with the study designs. There were no significant differences between the two groups on most baseline characteristics, except race, age, and BSI scores. AD patients were more likely to be Caucasian and Native American, older, and to score higher on the BSI compared to non-AD patients.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics by alcohol dependence status

| Variable | Non-Alcohol Dependent (n = 185) | Alcohol Dependent (n = 208) | Statistic (df) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment condition, % (n) | χ2(1) = 0.00 | .98 | ||

| Standard Care | 29.2 (54) | 29.3 (61) | ||

| Standard Care + CM | 70.8 (131) | 70.7 (147) | ||

| Agea | 34.83 ± 7.50 | 37.65 ± 7.62 | t(391) = -3.70 | <.001 |

| Annual incomea | $9,334.74 ± 12,943 | 9,906.75 ± 16,416 | t(391) = -3.80 | .70 |

| Brief Symptom Inventory, Global Severity Index score | 0.76 ± 0.68 | 1.02 ± 0.69 | t(391) = -3.71 | <.001 |

| Years of Educationa | 11.61 ± 1.53 | 11.56 ± 1.90 | t(391) = 0.26 | .80 |

| Gender,% (n) | χ2(1) = 0.92 | .34 | ||

| Male | 47.6 (88) | 52.4 (109) | ||

| Female | 52.4 (97) | 47.6 (99) | ||

| Race,% (n) | χ2(3) = 8.06 | .04 | ||

| Caucasian | 29.7 (55) | 38.9 ( 81) | ||

| African American | 56.2 (104) | 49.0 (102) | ||

| Hispanic | 13.5 (25) | 9.1 (19) | ||

| Native American | 0.5 (1) | 2.9 (6) | ||

| Marital status,% (n) | χ2(2) = 0.55 | .76 | ||

| Single | 55.1 (102) | 51.9 (108) | ||

| Other | 33.0 (61) | 34.1 (71) | ||

| Married | 11.9 (22) | 13.9 (29) | ||

| Site, % (n) | χ2(3) = 7.55 | .06 | ||

| A | 9.2 (17) | 6.7 (14) | ||

| B | 26.5 (49) | 39.4 (82) | ||

| C | 33.5 (62) | 28.8 (60) | ||

| D | 30.8 (57) | 25.0 (52) | ||

| Years of cocaine useb | 10.33 ± 6.9 | 11.35 ± 7.9 | F(1,390) = 2.17 | .14 |

Note. Values are percentages (ns in parentheses) unless otherwise specified. CM = contingency management.

Mean ± standard deviation

Age adjusted means and standard deviations

Table 2 shows baseline QOL scores for those with and without AD. After controlling for other variables, ANCOVA revealed significant effects of AD status, F (1,387) = 6.57, p = .01, with AD patients having lower QOL scores than non-AD patients. BSI scores were significantly and inversely related to QOL total scores, F (1, 387) = 51.34, p < .001. Race was also related to baseline QOL scores, with Caucasians having the lowest mean (SE) QOL score, 0.76 (0.17), and Native Americans and Hispanics the highest, 1.99 (0.74) and 1.93 (0.29), respectively. African Americans had intermediate QOL scores, 1.73 (0.13).

TABLE 2.

Baseline Quality of Life Inventory Scores by alcohol dependence status

| Non-Alcohol Dependent (n = 185) | Alcohol Dependent (n = 208) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | Statistic (df) | p |

| Total QOL score | 1.85 ± .24 | 1.39–2.31 | 1.36± .22 | 0.92–1.79 | F(1,387) = 6.57 | .01 |

| Relationship with children | 3.67± .40 | 2.89–4.46 | 2.84 ± .37 | 2.11–3.57 | F(1,387) = 6.50 | .01 |

| Relationship with relatives | 2.72 ± .37 | 2.01–3.44 | 2.22 ± .34 | 1.56–2.89 | F(1,387) = 2.79 | .10 |

| Love | 2.55 ± .41 | 1.75–3.35 | 1.64 ± .38 | 0.89–2.38 | F(1,387) = 7.46 | .007 |

| Friendship | 2.39 ± .34 | 1.71–3.06 | 1.58 ± .32 | 0.95–2.21 | F(1,387) = 8.23 | .004 |

| Philosophy of life | 2.16 ± .33 | 1.52–2.80 | 1.97 ± .31 | 1.37–2.57 | F(1,387) = 0.49 | .49 |

| Health | 2.08 ± .42 | 1.25–2.91 | 1.72 ± .39 | 0.95–2.49 | F(1,387) = 1.08 | .30 |

| Social service | 1.88 ± .32 | 1.25–2.50 | 1.53 ± .30 | 0.95–2.11 | F(1,387) = 1.77 | .18 |

| Creativity | 1.62 ± .33 | 0.97–2.26 | 1.36 ± .30 | 0.77–1.96 | F(1,387) = 0.89 | .35 |

| Home | 1.62 ± .41 | 0.81–2.44 | 0.85 ± .38 | 0.10–1.61 | F(1,387) = 5.19 | .02 |

| Self-regard | 1.51 ± .34 | 0.84–2.18 | 1.28 ± .32 | 0.66–1.91 | F(1,387) = 0.64 | .42 |

| Standard of living | 1.20 ± .41 | 0.39–2.01 | 0.54 ± .38 | -0.22–1.29 | F(1,387) = 3.79 | .05 |

| Learning | 1.16 ± .38 | 0.42–1.91 | 1.40 ± .36 | 0.70–2.10 | F(1,387) = 0.57 | .45 |

| Recreation | 1.12 ± .32 | 0.49–1.75 | 0.51 ± .30 | -0.07–1.10 | F(1,387) = 5.31 | .02 |

| Community | 1.02 ± .32 | 0.40–1.65 | 1.02 ± .30 | 0.44–1.61 | F(1,387) = 0.00 | .99 |

| Neighborhood | 1.00 ± .34 | 0.33–1.67 | 0.75 ± .32 | 0.13–1.38 | F(1,387) = 0.75 | .39 |

| Civic action | 0.98 ± .24 | 0.51–1.44 | 0.67 ± .22 | 0.24–1.11 | F(1,387) = 2.40 | .12 |

| Work | 0.89 ± .43 | 0.04–1.74 | -0.02 ± .40 | -0.82–0.77 | F(1,387) = 6.56 | .01 |

Note. CI= Confidence Interval

The MANCOVA evaluating baseline QOL subscale scores also revealed a significant effect of AD status, F (17,371) = 1.80, p = .03. Table 2 shows weighted means for the 17 subscales as a function of AD status. Six of the subscales differed significantly at p < .05 by AD status: work, recreation, love, friendship, relationship with children, and home. In each case, patients with AD had lower scores than those without AD. Again, race and baseline BSI scores were associated with individual subscale scores, F (51, 1119) = 1.95, p < .001 and F (17,371) = 5.81, p < .001, respectively. All 17 subscale scores were significantly (p < .01) and inversely associated with BSI scores, and all but five (work, recreation, friendship, neighborhood and community) differed by race (data not shown).

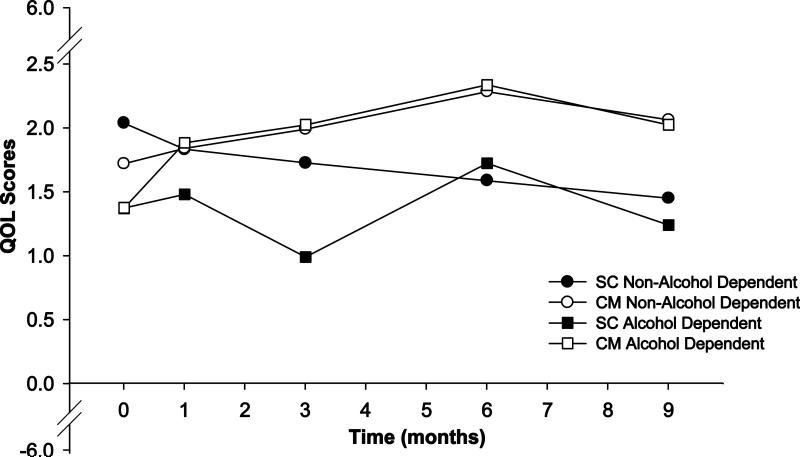

In the repeated measures ANOVA, neither AD status nor its interaction with treatment condition were associated with changes in QOL scores over time, F (4, 206) = 1.19, p = .32 and F (4, 206) = 0.62, p = .65, respectively. Treatment condition was related to changes in QOL scores, F (4, 206) = 2.57, p = .04, with patients assigned to the CM treatments showing increases in QOL over time and those assigned to SC evidencing no significant change (see Figure 1). Other covariates were not significant.

FIGURE 1.

Quality of Life Inventory Scores over time. Values represent weighted mean scores obtained by alcohol (squares) and non-alcohol (circles) dependent patients. Open and closed symbols depict contingency management (CM) and standard care (SC) treatment groups, respectively.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine QOL at baseline and over time in cocaine abusing outpatients with and without comorbid AD. AD patients had reduced baseline QOL scores compared to patients without AD. These results are consistent with other studies reporting that cocaine dependent individuals with comorbid AD have greater behavioral, psychological, and psychiatric impairment than individuals presenting with cocaine dependence alone.2–7

As mentioned before, there are relatively few examples of QOL research in the drug abuse literature. In one study in cocaine dependent patients, Havassy and Arns27 reported that hospitalized psychiatric patients with cocaine dependence had lower QOL than psychiatric patients with AD or other substance dependences. Comparison between that study and this one is complicated due to methodological differences (e.g., population, QOL assessment used). Nevertheless, our finding that patients with concomitant cocaine-alcohol use disorder have poorer QOL at treatment initiation than individuals presenting with cocaine abuse alone—a group known to have poor QOL—is concerning especially in light of the extremely high rates of co-occurring cocaine and alcohol use disorders in US population in general,1, 49 as well as community treatment settings.2–4

The analysis of the 17 subscales of the QOLI shows that patients with comorbid AD score lower than patients without AD on 6 of the 17 subscales primarily related to interpersonal relationships at treatment initiation. Although these results should be interpreted with caution due to multiple testing, they indicate that concomitant AD may have a greater negative impact on social relationships than some other domains. Clinical repercussions might be that patients with concurrent cocaine and alcohol use disorders may need greater social functioning support than some other groups of substance abusers. Knowledge of this deficit might help clinicians develop more targeted treatment plans for this patient population that specifically address social relations.

In regards to the relationship between CM and QOL, our analysis suggests that CM was associated with gains in QOL over time regardless of the presence of AD. In contrast, QOL did not significantly change over time in SC patients. In a previous study,50 we reported that cocaine treatment patients with and without comorbid AD responded equally well to CM treatment with respect to improved abstinence and decreased psychosocial problems as assessed by the Addiction Severity Index. The results presented here complement those findings using another outcome measure. Cocaine abusing patients with and without AD appear to respond similarly to CM across several QOL domains.

Although efficacious in improving end of treatment outcomes, CM benefits are not always maintained long-term. Further, improvements on secondary outcomes with CM are not consistently observed. In the present study, CM-related improvements in QOL over time were maintained through the Month 9 follow-up. In another study based on a retrospective analysis of the three studies examined here,50 we reported that CM-related improvements in psychosocial functioning in patients with AD were maintained through Month 9. Together, these studies provide some evidence that the benefits produced by exposure to CM treatment can extend to other areas of functioning, as well as beyond the treatment period.

Limitations of this study include the use of ANOVA to examine QOLI scores over time when there are missing data. Another limitation is the use of a combined sample from three clinical trials, which increases heterogeneity. Therefore, results should be interpreted with caution. Although there were some differences in the CM treatment applied across the trials (target behavior and reinforcer magnitude or type), all three clinical trials42–44 shared substantial similarities in terms of experimental procedures, goals, and treatment effects (see Method section and individual reports for more details). That long-term outcomes were limited to 9 months is also a limitation as longer follow-up would be preferable.

Strengths of this study are the broad inclusion criteria for participation, large sample size, and the inclusion of CM in combination with standard care in community-based treatment center clinics. These factors are likely to increase the generalization of these results. Another strength is the randomization of patients to study conditions.

In summary, although there has been a great increase in the number of studies involving QOL in the biomedical and health treatment research in general, few studies have used QOL indices to assess patient's well being and treatment outcomes in drug abuse research.11, 18, 20 This study sheds some light on the QOL of cocaine abusers with and without AD, a population on which research involving QOL has been scarce. The results presented here show that there are significant differences between the QOL of outpatient cocaine abusers with and without comorbid AD. At the time treatment is sought, cocaine abusing patients with AD have lower QOL total score as well as lower scores on several subscales related to social relationships than patients without AD. Furthermore, results indicate that cocaine abusing patients with and without AD showed similar improvement in QOL during CM treatment and beyond. Future studies involving this population might investigate the long term outcomes produced by CM over more extended periods of time.

Acknowledgements

This research and preparation of this report was funded by NIH grants P30-DA023918, T32-AA07290, R01-DA14618, R01-DA13444, R01-DA018883, R01-DA016855, R01-DA021567, R01-DA022739, R01-DA027615, R01-DA024667, R21-DA021836, P60-AA03510, P50-DA09241, and M01-RR06192.

References

- 1.Helzer JE, Pryzbeck TR. The co-occurrence of alcoholism with other psychiatric disorders in the general population and its impact on treatment. J Stud Alcohol. 1988;49:219–224. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Bryant KJ. Alcoholism in treatment-seeking cocaine abusers: Clinical and prognostic significance. J Stud Alcohol. 1993;54:199–208. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heil SH, Badger GJ, Higgins ST. Alcohol dependence among cocaine-dependent outpatients: Demographics, drug use, treatment outcome and other characteristics. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:14–22. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Foerg FE, Badger GJ. Alcohol dependence and simultaneous cocaine and alcohol use in cocaine-dependent patients. J Addict Dis. 1994;13:177–189. doi: 10.1300/j069v13n04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brady KT, Sonne S, Randall CL, Adinnof B, Malcolm R. Features of cocaine dependence with concurrent alcohol abuse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995;39:69–71. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(95)01128-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hedden SL, Malcolm RJ, Latimer WW. Differences between adult non-drug users versus alcohol, cocaine and concurrent alcohol and cocaine problem users. Addict Behav. 2009;34:323–326. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham SC, Corrigan SA, Malow RM, Smason IH. Psychopathology in inpatients dependent on cocaine or alcohol and cocaine. Psychol Addict Behav. 1993;7:246–250. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitz JM, Bordnick PS, Kearney ML, Fuller SM, Breckenridge JK. Treatment outcome of cocaine-alcohol dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997;47:55–61. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carroll KM, Power MD, Bryant K, Rounsaville BJ. One-year follow up status of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers: Psychopathology and dependence severity as predictors of outcome. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1993;181:71–79. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199302000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zubaran C, Foresti K. Quality of life and substance use: Concepts and recent tendencies. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:281–286. doi: 10.1097/yco.0b013e328328d154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Testa MA, Simonson DC. Assessment of quality of life outcomes. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:835–840. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603283341306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ware JE. SF-36 health survey update. In: Maruish MR, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcome assessment. 3rd ed Mahwah, NJ: 2004. 2004. pp. 693–718. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brogly S, Mercier C, Bruneau J, Palepu A, Franco E. Towards more effective public health programming for injection drug users: Development and evaluation of the injection drug user quality of life scale. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38:965–992. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petry NM, Alessi SM, Hanson T. Contingency management improves abstinence and quality of life in cocaine abusers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:307–315. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frisch MB. QOLI or Quality of Life Inventory. Pearson Assessments; Minneapolis, MN: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frisch MB, Cornell J, Villanueva M, Retzlaff P. Clinical validation of the Quality of Life Inventory: A measure of life satisfaction for use in treatment planning and outcome assessment. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:92–101. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frisch MB, Clark MP, Rouse SV, et al. Predictive and treatment validity of life satisfaction and the quality of life inventory. Assessment. 2005;12:66–78. doi: 10.1177/1073191104268006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donovan D, Mattson ME, Cisler RA, Longabaugh R, Zweben A. Quality of life as an outcome measure in alcoholism treatment research. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:119–139. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith KW, Larson MJ. Quality of life assessments by adult substance abusers receiving publicly funded treatment in Massachusetts. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2003;29:323–335. doi: 10.1081/ada-120020517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgan TJ, Morgenstern J, Blanchard KA, Labouvie E, Bux DA. Health-related quality of life for adults participating in outpatients substance abuse treatment. Am J Addict. 2003;12:198–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruldolf H, Watts J. Quality of life in substance abuse and dependency. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2002;14:190–197. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McKenna M, Chick J, Buxton M, Howlett H, Patience D, Riston B. The SECCAT survey: I. The costs and consequences of alcoholism. Alcohol Alcoho. 1996;31:565–576. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a008192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volk RJ, Cantor SB, Stenbauer JR, Cass AR. Alcohol use disorders, consumption patterns, and health-related quality of life of primary care patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:899–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foster JH, Marshall EJ, Hopper R, Peters TJ. Quality of life measures in alcohol dependent subjects and changes with abstinence and continued heavy drinking. Addict Biol. 1998;3:321–332. doi: 10.1080/13556219872137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Falck RS, Wang J, Carlson RG, Siegal HA. Crack-cocaine use and health status as defined by the SF-36. Addict Behav. 2000:579–584. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lozano OM, Domingo-Salvany A, Martinez-Alonso M, Brugal MT, Alonso J, de la Fuente L. Health-related quality of life in young cocaine users and associated factors. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:977–985. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9376-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Havassy BE, Arns PG. Relationship of cocaine and other substance dependence to well-being of high-risk psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49:935–940. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.7.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraemer KL, Maisto SA, Conigliaro J, McNeil M, Gordon AJ, Kelley ME. Decreased alcohol consumption in outpatient drinkers is associated with improved quality of life and fewer alcohol-related consequences. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:382–386. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foster JH, Marshall EJ, Peters TJ. Application of a quality of life measure, the Life Situation Survey (LSS), to alcohol-dependent subjects in relapse and remission. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24:1687–1692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emrick CD. A review of psychologically oriented treatment of alcoholism. I: the use and relationship of outcome criteria and drinking behavior following treatment. J Stud Alcohol. 1974;35:523–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pattison EM. A critique of abstinence criteria in the treatment of alcoholism. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1968;14:268–276. doi: 10.1177/002076406801400404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laudet AB, Becker JB, White WL. Don't wanna go through that madness no more: Quality of life satisfaction as predictor of sustained remission from illicit drug misuse. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44:227–252. doi: 10.1080/10826080802714462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Longabaugh R, Mattson ME, Connors GJ, Cooney NL. Quality of life as an outcome variable in alcoholism treatment research. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;12(Suppl):119–129. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Foster JH, Powell JE, Marshall EJ, Peters TJ. Quality of life in alcohol-dependent subjects. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:255–261. doi: 10.1023/a:1008802711478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins ST, Budney AJ, Bickel WK, Foerg FE, Donham R, Badger GJ. Incentives improve outcome in outpatient behavioral treatment of cocaine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:568–576. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950070060011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petry NM. A comprehensive guide to the application of contingency management procedures in general clinic settings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58:9–25. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, Kranzler HR. Give them prizes, and they will come: Contingency management for treatment of alcohol dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:250–257. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller P. A behavioral intervention program for public drunkenness offenders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975;32:915–918. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760250107012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Budney AJ, Higgins S, Delaney DD, Kent L, Bickel WK. Contingent reinforcement of abstinence with individuals abusing cocaine and marijuana. J Appl Behav Anal. 1991;24:657–665. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higgins ST, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Contingent methadone delivery: Effects on illicit-opiate use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1986;17:311–322. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(86)90080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roll J, Higgins ST, Badger GJ. An experimental comparison of three different schedules of reinforcement of drug abstinence using cigarette smoking as an exemplar. J Appl Behav Anal. 1996;29:495–505. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petry NM, Tedford J, Austin M, Nich C, Carroll KM, Rounsville BJ. Prize reinforcement contingency management for treatment of cocaine abusers: How long can we go, and with whom? Addiction. 2004;99:349–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petry NM, Alessi SM, Marx J, Austin M, Tardif M. Vouchers versus prizes: Contingency management treatment of substance abusers in community settings. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:1005–1014. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petry NM, Alessi SM, Carroll KM, et al. Contingency management treatments: Reinforcing abstinence versus adherence with goal-related activities. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:592–601. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and StatisticalManual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American PsychiatricAssociation; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 46.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—Clinician version. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Derogatis LR. Brief Symptom Inventory. Clinical Psychometric Research; Baltimore: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petry NM, Tedford J, Martin B. Reinforcing compliance with non-drug-related activities. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;20:33–44. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 1996-2006. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Rockville, MD: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rash CJ, Alessi SM, Petry NM. Cocaine abusers with and without alcohol dependence respond equally well to contingency management treatments. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16:275–181. doi: 10.1037/a0012787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]