Abstract

Neuroprotective properties of ketosis may be related to the up-regulation of hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1α), a primary constituent associated with hypoxic angiogenesis and a regulator of neuroprotective responses. The rationale that the utilization of ketones by brain results in elevation of intracellular succinate, a known inhibitor of prolyl-hydroxylase (the enzyme responsible for the degradation of HIF-1α) was deemed as a potential mechanism of ketosis on the up-regulation of HIF-1α. The neuroprotective effect of diet-induced ketosis (3 weeks of feeding a ketogenic diet), as pretreatment, on infarct volume, following reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) and the up-regulation of HIF-1α was investigated. The effect of beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB), as a pretreatment via intraventricular infusion (4 days of infusion prior to stroke) was also investigated following MCAO. HIF-1α and Bcl-2 (anti-apoptotic protein) protein levels, and succinate content were measured. A 55–70% reduction in infarct volume was observed with BHB infusion or diet-induced ketosis, respectively. HIF-1α and Bcl-2 protein levels increased 3-fold with diet-induced ketosis; BHB infusions resulted in increases in these proteins. As hypothesized, succinate content increased by 55% with diet-induced ketosis and 4-fold with BHB infusion. We conclude, the biochemical link between ketosis and the stabilization of HIF-1α is through the elevation of succinate, and both HIF-1α stabilization and Bcl-2 up-regulation play a role in ketone induced neuroprotection in brain.

INTRODUCTION

Ketone bodies, R-beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) and acetoacetate (AcAc), are alternate energy substrates to glucose and are utilized by the brain and most other tissues especially during early development and under conditions of reduced glucose availability, such as during starvation, fasting, heavy exercise and strict caloric intake of a high fat, low carbohydrate diet (Freeman et al. 1998; Melo et al. 2006; Veech 2004; Nehlig 2004). The relationship of ketone body metabolism by brain and neuroprotection continues to be investigated as there are many proposed mechanisms that ketones act through (for review, Prins 2008). In a rodent model of MCAO, infarct volume was reported to be reduced with ketosis as a result of inhibition of lipid peroxidation and hence reduction of reperfusion injury, as well as an overall improvement of cerebral energy metabolism (Suzuki et al. 2002). Neuroprotection by ketones has been proposed to be linked to glucose metabolism through the down regulation of glycolysis, possibly through decreased phosphoructokinase activity and thus, a reduction in lactic acid accumulation during ischemia (Gueldry et al. 1990). However, local cerebral glucose utilization measured by the [14C]2-deoxy-D-glucose method in conscious hyperketonemic rats (induced by fasting or exogenous infusion) showed no change in cerebral metabolic rate for glucose (Corddry et al. 1982).

Ketosis has been considered, and in some cases utilized, as a therapeutic strategy for the treatment of hypoglycemia, seizure disorders (induction of ketosis by ketogenic diet) and as an alternative to high lipid parenteral and enteral feedings (Desrochers et al. 1995; Freeman et al. 1998; Yudkoff et al. 2007). Since hyperglycemia has been known to exacerbate brain ischemic damage (Parsons et al. 2002; Tsuda 2006), one could hypothesize to use ketosis as a treatment to counteract the hyperglycemia. Ketosis has also been considered to improve hypoxic tolerance by improving metabolic energy state that results from an imbalance in glucose metabolism and energy insufficiency (Suzuki et al. 2002). Treatment with ketone body precursors such as 1,3-butanediol, has shown promising results with respect to diminished brain damage due to ischemia and/or reperfusion injury (Gueldry et al. 1990; Sims and Heward 1994).

A potential benefit of ketone bodies on improving overall physical and cognitive performance as well as protection from oxidative stress is thought to be linked to improved metabolic efficiency (Maalouf et al. 2007; Veech 2004). Ketone bodies are suggested to have a beneficial role in mitochondrial energy metabolism through the stabilization of redox, as well as non-oxidative metabolism such as through the activation of survival pathways (Guzman and Blazquez 2004; Kowaltowski et al. 2005; Sullivan et al. 2004; Suzuki et al. 2002; Veech 2004; for review, Prins, 2008). However, the biochemical and molecular mechanisms that link the metabolic effects of ketosis with neuroprotection remain to be discerned. In a recent review, neuroprotection by ketosis was discussed and at least 17 key findings associated with the use of ketone therapy in various CNS injury models were presented which suggests that ketones act through more than a single mechanism, but most likely through multiple mechansims (Prins, 2008).

A possible link between ketosis, neuroprotection and angiogenesis is through HIF-1α (Chávez et al. 2000). HIF-1α is a transcription factor related to the regulation of energy metabolism and is known to accumulate during hypoxia (Semenza, 2004). HIF-1α is thought to be one of the most crucial signaling molecules that results in upregulating survival pathways associated with oxygen deprivation, as well as mediating neuroprotective responses associated with metabolic compromise (Freeman and Barone 2005; Soucek et al. 2003). Our hypothesis was that the neuroprotective properties of ketosis is through the up-regulation of HIF-1α. The rationale was developed on the basis that the utilization of ketones results in the elevation of intracellular succinate. Increased succinate has been shown to induce HIF-1α through the inhibition of prolyl-hydroxylase (PHD; EC 1.14.11), the enzyme responsible for the degradation of HIF (Myllyla et al. 1977).

Results from our previous study suggest the link between ketosis and neuroprotection is related to angiogenesis (Puchowicz et al. 2007). The current study establishes a primary player associated with hypoxic angiogenesis, hypoxia inducible factor 1 (HIF-1α), is up-regulated in ketotic brains of normoxic rats either fed a ketogenic diet or by intraventricular infusion of the ketone body, BHB. From these data, together with our understanding of the regulation of HIF-1α, we explored a possible biochemical explanation that relates ketosis, angiogenesis and neuroprotection.

In this study we explored a potential biochemical mechanism related to the effects of ketosis on neuroprotection. We hypothesized that ketosis ameliorates the damage caused by reperfusion injury following stroke induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) in rat. Based on the rationale that cerebral utilization of ketone bodies has beneficial effects on ischemic response, diet-induced ketosis or brains intraventricularly infused with Na-BHB as a pretreatment on infarct volume following reversible MCAO was studied. Succinate content and HIF-1α response in ketotic rat brain were also studied.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Preparation and Feeding Conditions

All procedures were performed in strict accordance with the National Institutes of Health: The guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Case Western Reserve University. Male Wistar rats, 28 days old, weighing 110 g were allowed to acclimate in the CWRU animal facility for one week before being used in experiments. The experimental design consisted of two studies. Study 1: Rats were assigned randomly to three diet groups, fed ad libitum, ketogenic (high fat, no carbohydrate; KG), carbohydrate (high carbohydrate, low fat; CHO), or standard lab-chow (STD) diet for three weeks (Table 1) prior to experiments. The traditional standard diet (STD diet; Teklab 8664) was used as a control to the KG diet. In order to match the micronutrients (vitamin and mineral content*) and protein components of the KG diet, the CHO diet was used as an additional control (Research Diets; New Brunswick, NJ, U.S.A; KG#D12369b, CHO#D12359). Prior to feeding the diets all the rats were fasted for 18 h to stabilize the concentrations of glucosyl units (blood glucose levels), and to initiate a state of ketosis.

Table 1.

Diet Compositions*

| Three weeks of feeding: | Fat (%) | Protein (%) | Carbohydrate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ketogenic (KG) | 89.5 | 10.4 | 0.1 |

| High carbohydrate (CHO) | 11.5 | 10.4 | 78.1 |

| Standard (STD) | 27.5 | 20.0 | 52.6 |

for mix details see info@ResearchDiets.com mix-V10001)

We developed a diet-induced rat model of chronic ketosis by feeding a ketogenic diet (high fat, trace of carbohydrate; KG) to young adult rats. In this model we have shown that blood ketone levels are similar to what is measured in humans 3-day fasted or fed a ketogenic diet (Puchowicz et al. 2007). The advantages of inducing ketosis by feeding a KG diet is that ketosis can be sustained for days and months rather than hours (Desrochers et al. 1995) as with exogenous infusions of ketones or precursors of ketone bodies. This approach also eliminates the complications often encountered with exogenous administration of ketones as sodium salts or acids such sodium overload or vascular irritation.

Study 2: In another group of rats maintained on the standard diet only, local ketosis was mimicked by a continuous delivery of Na-BHB via intraventricular infusion. The purpose of this study was to determine if ketone bodies (delivered locally to brain) resulted in the same outcome as observed with diet induced ketosis. Mini osmotic Alzet pumps were implanted subcutaneously in the back of the neck and an infusion kit was used to administer Na-BHB (10mM, prepared in sterilized normal saline) into the lateral ventricle at a delivery rate of (1ul/hr) for 4 days prior to stroke (middle cerebral artery occlusion, MCAO). This direct approach enabled the testing of the effects of ketone bodies on neuroprotection, thus eliminating unknown or unexpected systemic effects of the KG diet. Additionally, to test the hypothesis that elevated succinate in brain results in neuroprotection, two other substrates, propionate and 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NPA) which are known to increase succinate levels were also investigated (1995 Martini et al. 2003; Hassel and Sonnewald, respectively). Na-propionate (1mM) and 3-NPA (1mM) were prepared in sterilized normal saline and administered via intraventricular infusion at the same rate as the Na-BHB for 4 days prior to stroke (middle cerebral artery occlusion, MCAO). Propionate and 3-NPA were used as positive controls to ketosis; although they are known toxins, we did not observe any neurological changes in these groups. To control for sodium vehicle another control group was infused with NaCl (1mM).

Experimental Set-up for MCAO and Molecular Analyses

Rats either ketotic by diet or substrate infused and their matched controls (non-ketotic diets or NaCl infused), were anesthetized with 2% halothane/O2/N2O and MCAO was performed using a monofilament model (Lust et al. 2002), occluded for 2h; rats were sacrificed at 24h of reperfusion and the infarct volumes determined (see below for description). MCAO infarct and edema volumes were measured in the diet-fed and infused groups. The analysis of proteins, HIF1-alpha and Bcl-2 (Western blot analysis) and mRNA expression of prolyl hydroxylase (PHD), as well as the succinate content (nmol/mg wet wt; GC-MS) required sub-group of rats either ketotic by diet or substrate infused where MCAO was not performed.

Infarct Volumes and Edema Measurements

The infarct volumes following focal cerebral ischemia (by MCAO) were determined by a standard procedure as previously described (Duverger and MacKenzie 1988). Rats were deeply anesthetized and transcardially perfused with ice cold heparinized-PBS (pH 7.4) buffer to remove the excess blood. Brains were removed, then sectioned (20µm coronal sections) on ice using cryostat blades and then stained histochemically with 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC). TTC staining measures tissue viability used to evaluate infarct size. Since ischemic regions tend to expand upon mounting the tissue to the slide (an approximation of edema), the infarct area was determined by measuring the total contralateral hemisphere and subtracting the normal tissue area on the ipsilateral hemisphere. This approach minimized the artifact of swelling and yielded a more accurate assessment of the actual infarct areas (Swanson and Sharpe 1994). The formula for infarct volume (Vi) is: Vi=3An d (80–100 µm), where An is the mean infarct area calculated as, Σ(contralateral-ipsilateral/ Σ(contralateral) *100, and d is the distance between the consecutive sections. Without the Swanson and Sharpe correction, edema volumes were then approximated by subtracting the contralateral from the edema hemisphere (ipsilateral hemisphere). All measurements were blinded and randomized.

HIF-1α and Bcl-2 Protein by Western Blot Analysis

In another set of animals (non MCAO), HIF-1α and Bcl-2 protein content was studied in the diet-induced ketotic rat brain or brains infused with substrate using Western Blot analysis. Animals were deeply anesthetized with halothane/O2/N2O and decapitated. The brains were quickly removed, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. Cortical (frontal or parietal regions, approximately 50–100 mg wet/wt) samples were dissected from either right or left hemispheres and homogenized in ice-cold buffer: 250 ml of buffer A (20mM HEPES, 1.5mM MgCl2, 0.2mM EDTA, 100mM NaCl, 0.5mM PMSF, 1µg/ml leupeptin, 0.2mM DTT, pH 7.4). Additional NaCl was added to the homogenate to make a final concentration of 0.45M NaCl. The homogenate was mixed and then placed in a centrifuge for 30 min at 14000 rpm at 4°C. The supernatant was collected (lysate) and measured so that an equal volume of buffer B (buffer A, plus 40% glycerol; vol/vol) was added before being stored at −80°C. Lysate samples were then analyzed for protein concentration using the Bradford Assay method prior to electrophoresis for Western blotting. (Agani et al. 2002)

Equal quantities of protein (100 µg of the lysate) were boiled with gel loading buffer for 5 minutes prior to loading onto a 10% SDS-PAGE. Separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using a Bio-Rad semidry transfer apparatus. Blots were blocked overnight in 5% skim milk powder in PBS-Tween 20 (PBST) at 4°C, and probed with anti-Bcl-2, anti-β-actin (both Santa Cruz; Santa Cruz, CA) or anti-HIF-1α , a generous gift from Dr. F. Agani, (Case Western Reserve University, Department of Anatomy), with 3% BSA in PBST. Blots with bound primary antibody were incubated with peroxidase labeled secondary antibodies (Jackson; West Grove, PA). Detection of the bound secondary antibody employed the Pierce (Rockford, IL) ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagents. Densitometry was performed with SigmaScan Pro5™ image analysis software, and values were normalized to β-actin content and expressed as relative intensity.

Prolyl Hydroxylase mRNA Expression by Real Time PCR

Prolyl hydroxylase mRNA expression, by real time PCR, was studied in the diet-induced ketotic rat brain (non MCAO). Cortical (frontal or parietal regions, approximately 50–100 mg wet/wt) samples from freshly dissected (either right or left hemispheres) and quickly homogenized in guanidine-isothiocyanate containing lysis buffer (RLT buffer) and RNA was isolated using the Quiagen RNeasy kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Quiagen, Valencia, CA.). Five micrograms of total RNA was treated with DNAse I (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA), then first strand cDNA synthesis was carried out using a reverse transcription reaction, using oligo d(T)15 (Promega; Madison WI) and Superscript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies; Rockville, MD). PCR amplification and detection was performed using Bio-Rad i-Cycler™ detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) in a total volume of 25µl containing 50 mM KCl, 20mM Tris-HCl, (pH 8.4), 0.2mM of each dNTP, 25 U/ml iTaq DNA polymerase, 3mM MgCl2, SYBR Green I, 10nM fluorescein, and stabilizers. Each reaction also contained 300nM of primer. Primer sequences for prolyl hydroxylase were TGT TGG ATC AGA ACC ACG ACG GTC (forward) and GAG TCA TCC ACC GTC CAT TT (reverse). Each amplification was performed in triplicate, using the following conditions: 3 minutes at 95°C, 30 seconds at 95°C and 30 seconds at 60°C through 40 cycles, followed by 2 temperature cycles (30 seconds at 72°C and 1 minute 60°C). A melt curve protocol (70 cycles with from 60°C to 95°C, with 0.5°C/cycle increments) was performed following each amplification to assess the purity of the product. In addition, amplified products for each primer set were analyzed using electrophoresis to confirm product size and purity. Relative expression was calculated by comparing the cycle thresholds for the genes of interest with cycle thresholds for β-actin mRNA.

Succinate Content

Succinate content (nmol/mg wet wt) was analyzed from extracts prepared from quick frozen (using liquid nitrogen and store at −80°C) cortical brains. Samples were collected from the frontal region (right or left hemisphere, weighing approximately 50 mg wet/wt) from either diet-induced ketotic rat brain or brains infused with substrate. Frozen samples were spiked with internal standard [U-13C4 ]succinate (Isotec-Miamisburg, OH), acidified with sulfosalicylic acid and homogenized with choloroform-methanol (2:1) solvent mixture at −25°C using a Polytron homogenizer. Extracts were then analyzed using gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC-MS) on an Agilent 5973 mass spectrometer, equipped with an Agilent 6890 gas chromatograph and an HP-5MS 5% phenyl methyl siloxane fused silica capillary column (60m, 250µm inner diameter, 0.25 mm film thickness). Sample preparation and GC-MS procedures were performed as previously described (Yang et al. 2006).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed on the data collected from the diet groups, KG, CHO, and STD and substrate infused groups, Na-BHB, 3-NPA, Na-propionate, and NaCl; the numbers (n’s) per group are noted in the results section for each analysis. All data were calculated as the mean ± SD. Group comparisons were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc method. The significance was considered at p<0.05.

RESULTS

Infarct and Edema Volumes

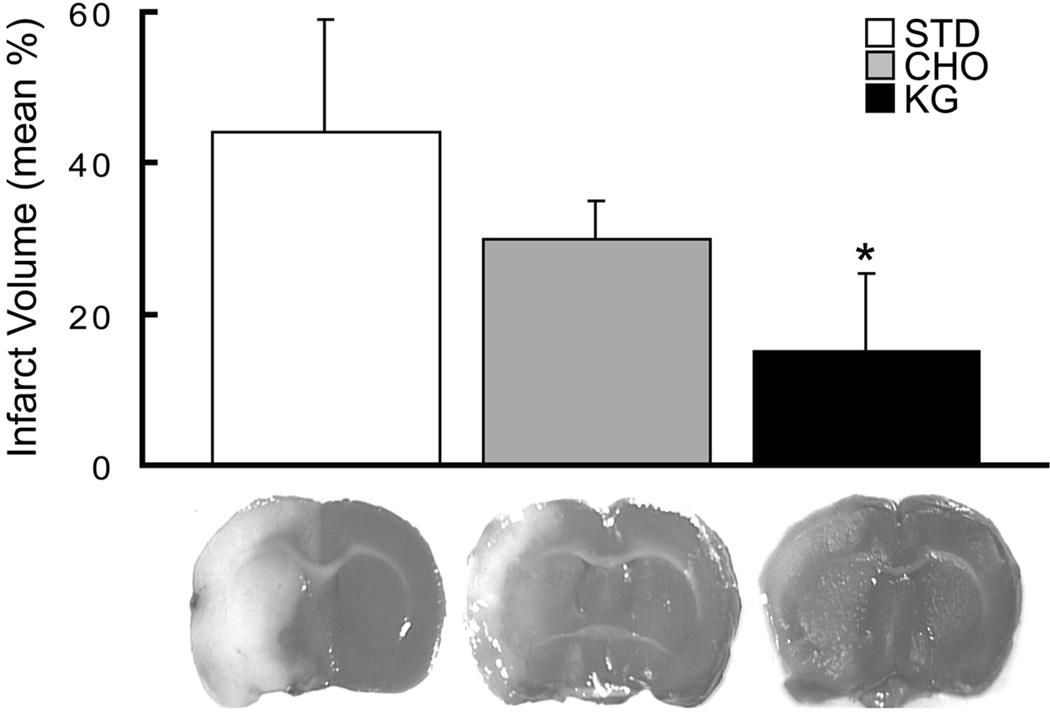

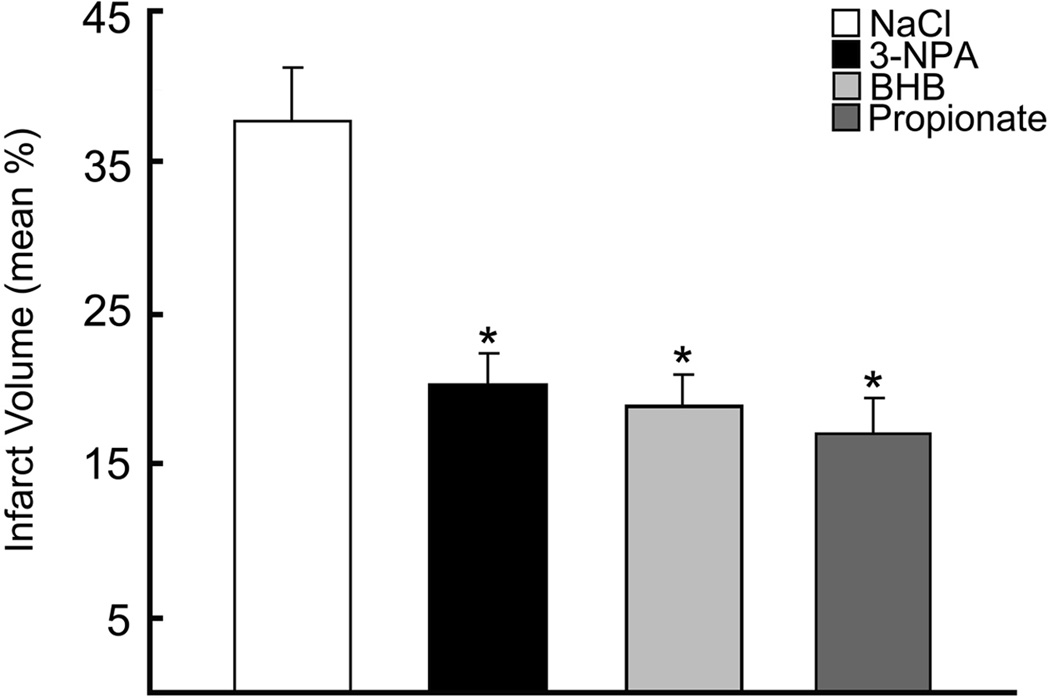

Infarct volumes were measured in rats fed the three diets, STD (n=11), CHO and KG (n=9). The infarct volumes at 24h of reflow after 2h occlusions for each of the diet groups were 45.9 ± 21.5, 30.2 ± 5.1 and 14.4 ± 9.6 % of the ipsilateral hemisphere, respectively (Figure 1). When comparing the relative changes in the infarct volumes, the KG diet group compared to the STD (68.7 ± 22.1 %) and CHO (52.4 ± 11.0 %) diet groups, was significantly lower. There was no significant difference in infarct volumes between the CHO and STD diet group. The corresponding edema volumes were also significantly decreased in the KG diet group by 50% (119 ± 62.9) compared to the STD and CHO groups (239 ± 147.0; 212 ± 47.6, respectively). The infarct volumes measured in rats (non KG-diet treated) with ventricular infusions of BHB, 3-NPA, or propionate, (n=6 per group), were also significantly reduced by 50% compared to the NaCl infused control group, (Figure 2). These results were consistent with the reduction in infarct volumes measured in the diet induced-ketotic group.

Figure 1. Decreased infarct volume in diet-induced ketotic rat brain.

Infarct volumes as determined by TTC staining in the diet-fed groups (STD-control, CHO, KG) are presented as the mean % infarct volume of the ipsilateral hemisphere. Measurements were blinded and randomized.

Figure 2. Decreased infarct volumes in substrate infused rat brain.

Infarct volumes as determined by TTC staining in the substrate infused groups (NaCl-control, BHB, 3-NPA, Propionate) are presented as the mean % infarct volume of the ipsilateral hemisphere. Measurements were blinded and randomized.

HIF-1α, Bcl-2 protein and Prolyl-hydoxylase mRNA content

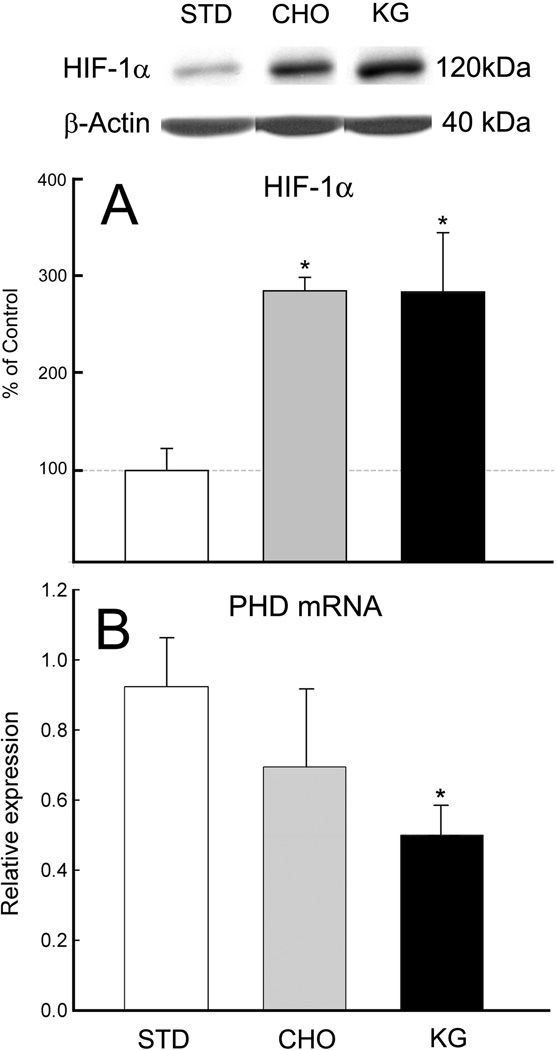

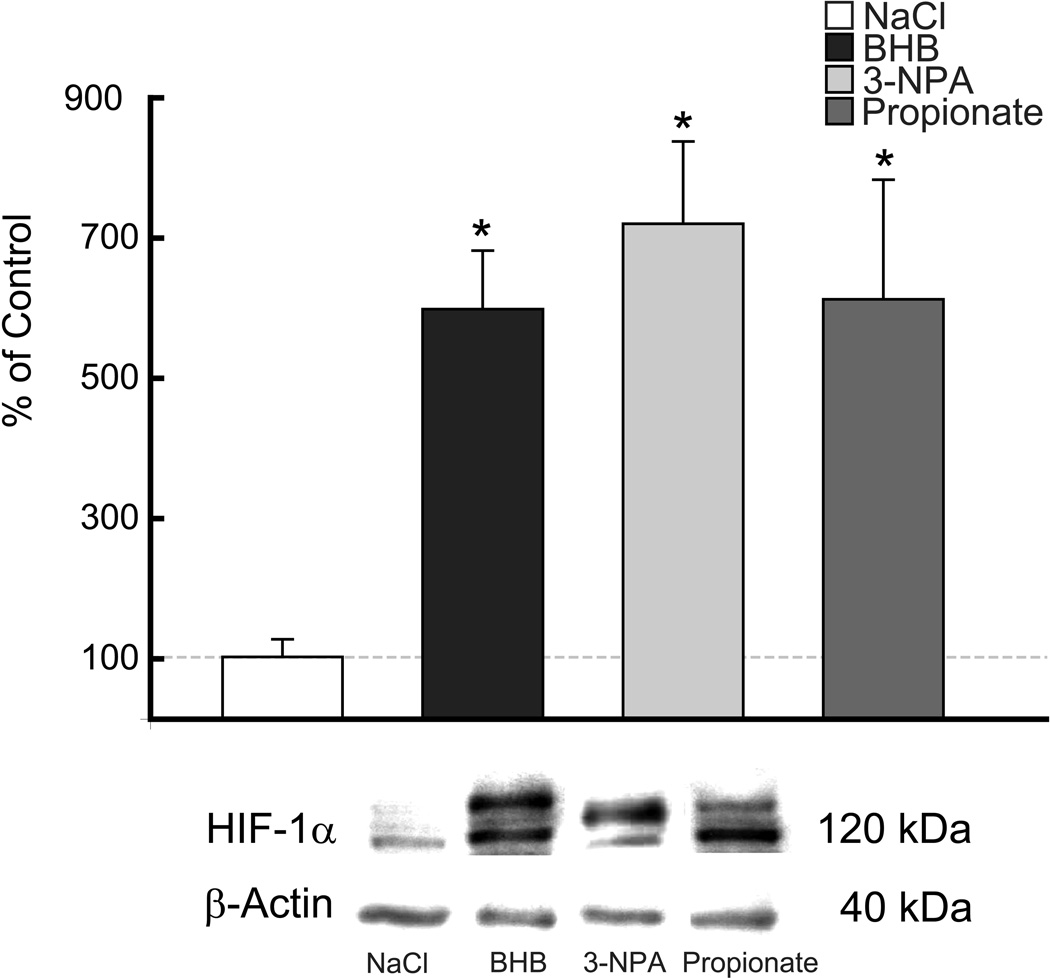

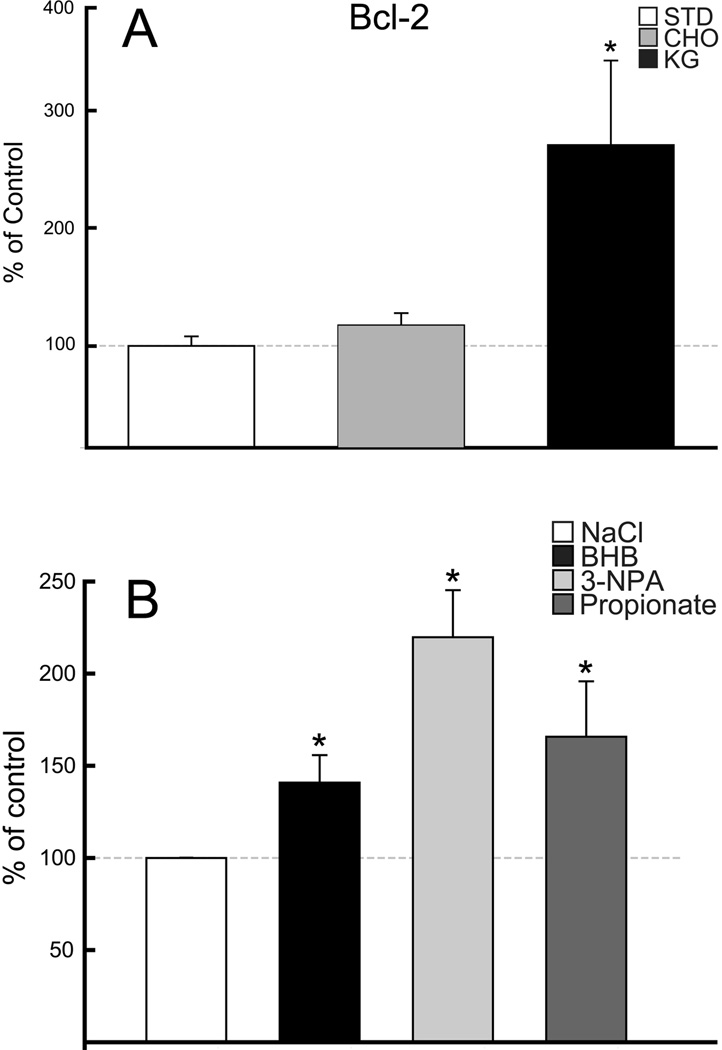

HIF-1α protein was elevated in the rats fed the KG diet or BHB infused compared to matched controls (STD diet or NaCl-infused), (n=5 per diet group; n= 12 per infused group). Similarly, an increase in HIF-1α protein was also observed with the CHO diet group as well as the 3-NPA or propionate infused. Western blot analysis revealed in the alternate diet-fed rats (CHO, KG), that HIF-1α was elevated significantly from 3-fold to 7-fold in the infused groups, 3-NPA, BHB and propionate, respectively (Figures 3A & 4). The diet groups were also analyzed for prolyl-hydoxylase (PHD) mRNA content. Consistent with the increase in HIF-1α protein level in the KG diet group, the PHD mRNA expression decreased (Figure 3B). Although the CHO diet group showed a downward trend in PHD mRNA content this was not significant. These results suggest less overall activity of the PHD in the rats fed the KG diet which does not appear to be the case for the CHO diet group. In the same group of diet-fed rats, the analysis of Bcl-2 protein was also elevated 3-fold in the KG diet group (Figure 5A). However, unlike the HIF-1α protein, there was no relative up-regulation of Bcl-2 in the CHO diet-fed rats.

Figure 3. HIF1-α protein and PHD mRNA expression in diet-induced ketotic rat brain.

Western blot and densitometric analysis revealed a 3-fold increase in the HIF1-α protein levels in CHO and KG diet groups (A), whereas prolyl-hydroxylase mRNA expression decreased in KG diet-fed rats (B). Data are expressed as % of STD-control diet or relative expression.

Figure 4. Up-regulation of HIF-1α protein in substrate infused rat brain.

Western blot and densitometric analysis revealed a 5-fold increase in HIF1-α protein levels in each of the substrate intraventricular infused rats (BHB, 3-NPA, Propionate) compared to NaCl-control. Data are expressed as % of NaCl-control.

Figure 5. Up-regulation of Bcl-2 protein.

Western blot and densitometric analysis revealed a 3-fold increase in Bcl-2 protein levels with diet induced ketosis and no change with CHO diet, compared to the STD-control group (A), and 1.5–2-fold increase in Bcl-2 protein was observed in each of the substrate infused groups compared to NaCl-control group (B). Data are expressed as % of STD-control diet or NaCl-control.

As observed with the diet-fed groups, Western blot analysis revealed an up-regulation of Bcl-2 in each of the substrate infused rats (BHB, 3-NPA, and propionate) (Figure 5B). Bcl-2 protein increased by 50% in the BHB infused group compared to the NaCl-infused controls. A similar increase was measured in the propionate infused group. The greatest induction of Bcl-2 was observed in the 3-NPA group (2-fold relative to NaCl infused controls).

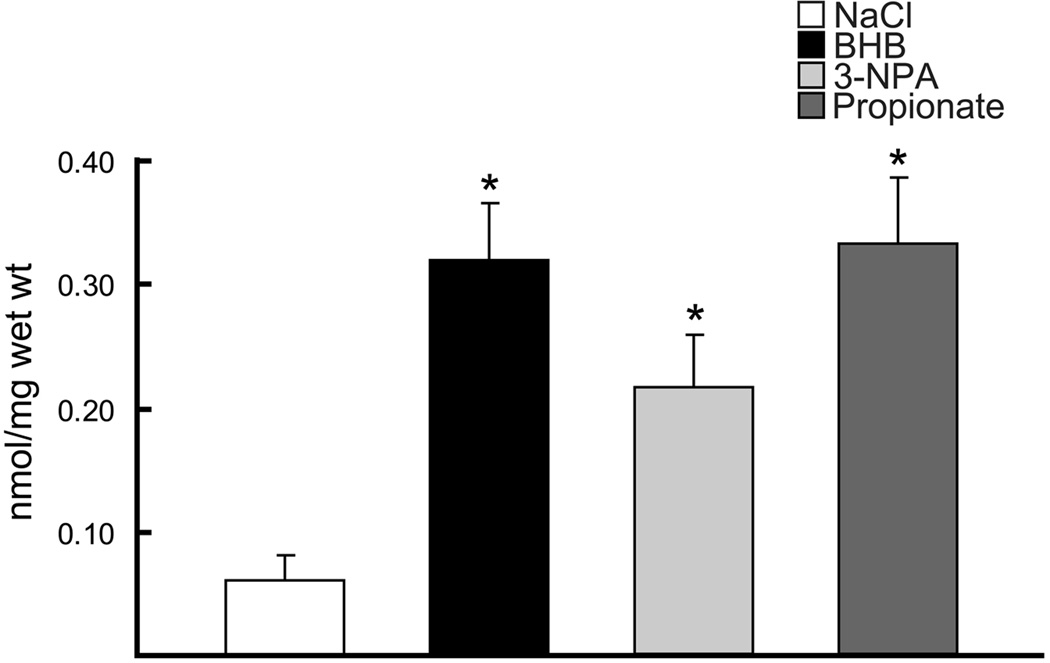

Succinate content

Succinate content (nmol/mg wet wt) was measured in the diet-fed groups (STD, KG) and substrate infused rat brains (NaCl, BHB, 3-NPA, propionate) and in both conditions (diet induced ketosis and BHB-substrate infused) succinate was significantly elevated compared to STD diet or NaCl controls. As expected the succinate content in 3-NPA and propionate infused groups were also significantly increased (similar to what was observed with the KG diet and BHB-infused). These two substrate-infused groups were added as positive controls, as these compounds are known to result in increased succinate levels. Gas chromatography mass-spectrometry analysis revealed that in brain tissue preps for succinate concentrations, the KG diet-fed group was significantly elevated by 1.6-fold (0.28 ± 0.08) compared to STD diet group (0.18 ± 0.02) (Goldberg et al. 1966). The succinate levels measured in the substrate infused groups were similar to what was measured in the KG diet-fed group, as there was a 5-fold increase with BHB and propionate infused and a 3-fold increase in the 3-NPA group, compared to NaCl-infused control group (0.06 ± 0.04) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Succinate content in the substrate infused groups.

Gas chromatography mass-spectrometry analysis of succinate concentrations in BHB-substrate infused brains were significantly elevated 5–fold compared to the NaCl-control and similar to the positive controls (3-NPA and Propionate, as these toxic compounds are known to result in increased succinate levels). Data are expressed as nmol/mg wet wt.

DISCUSSION

The role of ketone bodies as alternate energy substrates in brain has prompted investigators to explore their potential use as a therapeutic treatment modality against neurodegenerative disease, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Freidreich’s Ataxia, ALS, and against ischemic reperfusion injury (Kashiwaya et al. 2000; Zhao et al. 2006). Although the associated mechanisms remain unknown, it is hypothesized that ketone bodies play a neuroprotective role by improving metabolic efficiency, sparing of glucose oxidation and degradation of muscle-derived amino acids, and in some neurodegenerative conditions protect against glutamate cytotoxicity. In this study, we report a significant reduction in infarct volume following MCAO in diet-induced ketotic rats or intraventricular-infused with Na-BHB.

We have previously shown an increase in brain capillary density in our 3 week diet-induced rat model of ketosis (Puchowicz et al. 2007), similar to what has been observed in non-ketotic rat brain following 3 weeks of hypobaric-hypoxic induced angiogenesis (Pichiule and LaManna 2002). Angiogenesis has been recognized to play an important role associated with improved outcome from stroke (Slevin et al. 2006). The data from this study resulted in a significant elevation in succinate levels in ketotic rat brain. Ketone body metabolism has been known to result in increased levels of citric acid cycle intermediates such as citrate and succinate and thus we hypothesized that the metabolic side of HIF-1α regulation via ketosis is through the product inhibition of the PHD by succinate (Myllyla et al. 1977; Selak et al. 2005), an intermediate of energy metabolism (see Scheme). Succinate is produced as an intermediate of the citric acid cycle (mitochondria) through a series of reactions which uses 2-oxoglutarate (also known as 2-ketoglutarate) and succinyl-CoA as substrates, and the enzymes, 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex and succinyl-CoA synthetase, respectively. In the cytosol, succinate is a product of the conversion of 2-oxoglutarate by the PHD enzyme when oxygen is not limiting.

Succinate and 2-oxoglutarate can be transported across the mitochondrial membranes via specific substrate transporter systems which stabilize a “redox” balance between forward and reverse reactions. An acute shift in redox state results in biochemical perturbations that act as signal tranducers. Our rationale is that the stabilization of HIF-1α is through the inhibition of the cytosolic enzyme PHD via succinate, and thus inhibits the forward biochemical reaction that requires 2-oxoglutarate (Acker and Acker 2004; Dalgard et al. 2004). Consistent with our hypothesis, a significant decrease in PHD mRNA expression in the ketotic rat brain was also observed. Others have shown similar results where HIF-1α accumulation without hypoxic stimulation was as a result of the inhibition of PHD through the chelation of iron (Myllyla et al. 1977; Park et al. 2007). These and other studies have investigated the potential role of HIF-1α in neuro-protective preconditioning (Freeman and Barone 2005; Soucek et al. 2003).

Since HIF-1α has been described to regulate genes involved with energy metabolism and anti-apoptosis (Dery et al. 2005; Selak et al. 2005; Soucek et al. 2003) we also tested the possibility that this transcription factor is related to neuroprotection through the up-regulation of Bcl-2 protein, an anti-apoptotic protein. This multifunctional protein is a key regulator of apopotosis that either results in cell death or survival. It protects against apopotosis (anti-apoptotic mechanism) and necrosis through the regulation of mitochondrial redox or stabilization of the mitochondrial membrane by interfering with the activation of pro-apoptotic proteins such as cytochrome c (Kowaltowski and Fiskum 2005; Tsujimoto 2003). We found that ketosis, and the associated induction of HIF-1α, also resulted in a significant up-regulation the Bcl-2 protein (as shown in Figure 5). These results together with the increase in succinate levels suggest that neuroprotection by ketosis involves the regulation of biochemical and molecular pathways.

Elevated HIF-1α levels in the brain of the carbohydrate diet group were similar to what was found in the ketotic group; this was unexpected and cannot be explained by this study. The purpose of feeding the carbohydrate diet was to add an additional control to the ketogenic diet, as we felt that the standard rodent chow (Teklad) was not a sufficient control diet since it was manufactured by a different company. However, in this diet group there was no neuroprotection following MCAO or up-regulation of Bcl-2 and thus we concluded that the up-regulation of HIF-1α in the carbohydrate group was not the only regulatory mechanism responsible for neuroprotection. These data show that increased levels of HIF-1α alone do not result in neuroprotection and that neuroprotection by ketosis may require both the stabilization of HIF-1α and up-regulation of Bcl-2.

To further investigate if elevated HIF-1α and succinate levels in brain of ketotic rats chronically fed a ketogenic diet were not a result of an unknown systemic effect of the diet, we also explored if ketones administered locally by intra-ventricular infusion of Na-BHB in brains of non-ketotic rats and found the same degree of neuroprotection, as measured by decreased infarct volume following MCAO. Increased succinate content and HIF-1α and Bcl-2 protein levels were also observed. These results were consistent with the results observed with ketosis induced by diet.

One mechanism explaining the therapeutic effects of ketones is through the partitioning of glucose away from oxidative metabolism towards the replenishment of the citric acid cycle intermediates (anaplerosis). Propionate (or propionate carnitine esters), a known anaplerotic substrate, has been shown experimentally to protect the heart from reperfusion injury (Ferrari et al. 2004; Reszko et al. 2003). Propionate, when metabolized, enters the citric acid cycle as succinyl-CoA. The notion that anaplerosis is a beneficial process in protecting brain against reperfusion injury, has become become increasingly intriguing (Mason et al. 2007; Mochel et al. 2005).

We recognized that multiple mechanisms exist for the action of ketosis. In this study, the biochemical mechanism associated with neuroprotection, up-regulation of HIF-1α, and succinate was further explored in another group of rats where propionate or 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NPA) was infused intra-ventricularly. These compounds are known to increase intracellular succinate and were used to test if an increase in succinate levels without ketosis results in succinate-linked neuroprotection following MCAO and were not studied as treatment strategies against reperfusion injury for they are known to be toxic. We concluded that the resultant neuroprotection with ketosis (induced by diet or locally by intra-ventricular infusion of BHB), together with induction of HIF-1α and Bcl-2, was through the purported action of succinate. These data suggest a link between ketosis and neuroprotection is through the metabolic side of HIF. Since ketosis persisted both during and after ischemia, it was unclear at what stage the ketosis was neuroprotective.

CONCLUSION

Ketosis (induced by diet or by local intraventricular infusion of Na-BHB) significantly reduced infarct volumes by approximately 55% over those of control following 2 h of ischemia and 24 h of reflow. These data indicate that (i) the biochemical link between ketosis and the stabilization of HIF-1α is through the elevation of succinate and (ii) both HIF-1α stabilization and Bcl-2 up-regulation play a role in ketone induced neuroprotection in brain. This study establishes that ketosis as pretreatment is neuroprotective but does not ascertain whether the effectiveness occurs during ischemia and/or reperfusion. Although there is a clinical relevance on the use of ketosis (induced by diet or infusion) as a potential treatment for stroke, the use of the ketogenic diet as a pretreatment for those at risk for stroke has not been established. The transcriptional regulation of HIF-1α through the succinate-dependent mechanism remains to be explored. Pharmacological treatment regimes (preconditioning or post ischemia) that explore the use of ketones (or ketone body analogues) as a strategy towards increased neuroprotection are needed.

Supplementary Material

Our schema of the neuroprotective properties of ketone bodies relates ketone body metabolism to the stabilization of HIF-1α through product inhibition of prolyl hydoxylase (PHD) by succinate as follows: the fate of glucose (via glycolysis) and ketone bodies (acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate; AcAc, BHB) in brain mitochondria enter the citric acid cycle as acetyl-CoA residues and through a condensation reaction with oxaloacetate, catalyzed by citrate synthase, form citrate. Succinate is generated by the catabolism of acetyl-CoA via the citric acid cycle and through the activation of AcAc to AcAc-CoA via the enzyme succinyl-CoA-acetoacetate-CoA transferase (β-oxoacid-CoA-transferase). Activation of AcAc to AcAc-CoA requires succinyl-CoA as CoA donor and the resultant product is succinate. The proposed mechanism for the stabilization of HIF-α is shown to occur through the accumulation of mitochondrial succinate. With ketone body utilization mitochondrial succinate is elevated; maintaining the succinate mitochondrial pool would require transport of succinate out of the mitochondria via dicarboxylic acid transporter system into the cytosol. Elevation of succinate in the cytosol results in stabilization of HIF-1α through the product inhibition of PHD. During conditions when succinate does not accumulate, PHD is the enzyme which catalyzes the reaction of HIF-1α to the hydroxylated form (OH-HIF-1α) and undergoes proteasome degradation. Hydroxylation also requires 2-oxoglutarate* as a substrate and generates succinate as a co-product. The resultant increase in HIF-1α stimulates the production of a vasogenic activator (VEGF), erythropoietin and survival pathways, through the activation of related target genes, including Bcl-2. (Note the nomenclature for 2-oxoglutarate*, also known 2-ketoglutarate, refers to the cytosolic substrate, whereas 2-ketoglutarate notation in the citric acid cycle refers to the mitochondrial substrate).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Constantinos P. Tsipis for technical efforts and assistance on the preparation of this manuscript and Dr. H. Brunengraber, Department of Nutrition, Case Western Reserve University, and his staff, especially Lili Yang, for their generous support with the analysis of succinate content and use of the gas-chromatograph mass spectrometer. We also thank Dr. Faton Agani, Case Western Reserve University, Department of Anatomy for his generous gift of anti-HIF-1α.

GRANTS

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants NS-46074 and GM-066309.

Reference List

- Acker T, Acker H. Cellular oxygen sensing need in CNS function: physiological and pathological implications. J Exp Biol. 2004;207(Pt 18):3171–3188. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez JC, Agani F, Pichiule P, LaManna JC. Expression of hypoxic inducible factor 1α in the brain of rats during chronic hypoxia. J.Appl.Physiol. 2000:891937–891942. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.5.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corddry DH, Rapoport SI, London ED. No effect of hyperketonemia on local cerebral glucose utilization in conscious rats. J Neurochem. 1982;38:1637–1641. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1982.tb06644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalgard CL, Lu H, Mohyeldin A, Verma A. Endogenous 2-oxoacids differentially regulate expression of oxygen sensors. Biochem.J. 2004;380(Pt 2):419–424. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dery MA, Michaud MD, Richard DE. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: regulation by hypoxic and non-hypoxic activators. Int.J Biochem.Cell Biol. 2005;37(3):535–540. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrochers S, Quinze K, Dugas H, Dubreuil P, Bomont C, David F, Agarwal KC, Kumar A, Soloviev MV, Powers L, Landau BR, Brunengraber H. R,S-1,3-butanediol acetoacetate esters, potential alternates to lipid emulsions for total parenteral nutrition. J.Nutr.Biochem. 1995:6111–6118. [Google Scholar]

- Duverger D, MacKenzie E. The quantification of cerebral infarction following focal ischemia in the rat: Influence of strain, arterial pressure, blood, glucose, and age. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1988:8449–8461. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1988.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari R, Merli E, Cicchitelli G, Mele D, Fucili A, Ceconi C. Therapeutic effects of L-carnitine and propionyl-L-carnitine on cardiovascular diseases: a review. Ann.N.Y.Acad Sci. 2004:103379–103391. doi: 10.1196/annals.1320.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JM, Vining EPG, Pillas DJ, Pyzik PL, Casey JC, Kelly MT. The efficacy of the ketogenic diet- 1998: a prospective evaluation of intervention in 150 children. Pediatrics. 1998 Dec.102:1358–1363. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.6.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman RS, Barone MC. Targeting hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) as a therapeutic strategy for CNS disorders. Curr.Drug Targets.CNS.Neurol.Disord. 2005;4(1):85–92. doi: 10.2174/1568007053005154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg ND, Passonneau JV, Lowry OH. Effects of changes in brain metabolism on the levels of citric acid cycle intermediates. J Biol Chem. 1966;241(17):3997–4003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueldry S, Marie C, Rochette L, Bralet J. Beneficial effect of 1,3-butanediol on cerebral energy metabolism and edema following brain embolization in rats. Stroke. 1990;21(10):1458–1463. doi: 10.1161/01.str.21.10.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman M, Blazquez C. Ketone body synthesis in the brain: possible neuroprotective effects. Prostaglandins Leukot.Essent.Fatty Acids. 2004;70(3):287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassel B, Sonnewald U. Selective inhibition of the tricarboxylic acid cycle of GABAergic neurons with 3-nitropropionic acid in vivo. J Neurochem. 1995;65(3):1184–1191. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65031184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwaya Y, Takeshima T, Mori N, Nakashima K, Clarke K, Veech RL. D-beta-hydroxybutyrate protects neurons in models of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2000;97(10):5440–5444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.10.5440. 2000. May.9;97(10):5440-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowaltowski AJ, Fiskum G. Redox mechanisms of cytoprotection by Bcl-2. Antioxid.Redox.Signal. 2005;7(3–4):508–514. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lust WD, Taylor C, Pundik S, Selman WR, Ratcheson RA. Ischemic cell death: dynamics of delayed secondary energy failure during reperfusion following focal ischemia. Metab Brain Dis. 2002;17(2):113–121. doi: 10.1023/a:1015420222334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maalouf M, Sullivan PG, Davis L, Kim DY, Rho JM. Ketones inhibit mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species production following glutamate excitotoxicity by increasing NADH oxidation. Neuroscience. 2007;145(1):256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini WZ, Stanley WC, Huang H, Rosiers CD, Hoppel CL, Brunengraber H. Quantitative assessment of anaplerosis from propionate in pig heart in vivo. Am.J.Physiol Endocrinol.Metab. 2003;284(2):E351–E356. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00354.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason GF, Petersen KF, de Graaf RA, Shulman GI, Rothman DL. Measurements of the anaplerotic rate in the human cerebral cortex using 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy and [1-13C] and [2-13C] glucose. J Neurochem. 2007;100(1):73–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melo TM, Nehlig A, Sonnewald U. Neuronal-glial interactions in rats fed a ketogenic diet. Neurochem Int. 2006;48(6–7):498–507. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2005.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochel F, DeLonlay P, Touati G, Brunengraber H, Kinman RP, Rabier D, Roe CR, Saudubray JM. Pyruvate carboxylase deficiency: clinical and biochemical response to anaplerotic diet therapy. Mol Genet.Metab. 2005;84(4):305–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myllyla R, Tuderman L, Kivirikko KI. Mechanism of the prolyl hydroxylase reaction. 2. Kinetic analysis of the reaction sequence. Eur.J Biochem. 1977;80(2):349–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehlig A. Brain uptake and metabolism of ketone bodies in animal models Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent.Fatty Acids. 2004;70(3):265–275. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SS, Bae I, Lee YJ. Flavonoids-induced accumulation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha/2alpha is mediated through chelation of iron. J Cell Biochem. 2007 doi: 10.1002/jcb.21588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons MW, Barber PA, Desmond PM, Baird TA, Darby DG, Byrnes G, Tress BM, Davis SM. Acute hyperglycemia adversely affects stroke outcome: a magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy study. Ann.Neurol. 2002;52(1):20–28. doi: 10.1002/ana.10241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichiule P, LaManna JC. Angiopoietin-2 and rat brain capillary remodeling during adaptation and deadaptation to prolonged mild hypoxia. J Appl.Physiol. 2002;93(3):1131–1139. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00318.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prins ML. Cerebral metabolic adaptation and ketone metabolism after brain injury. J Cereb.Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28(1):1–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchowicz MA, Xu K, Sun X, Ivy A, Emancipator D, LaManna JC. Diet-induced ketosis increases capillary density without altered blood flow in rat brain. Am.J Physiol Endocrinol.Metab. 2007;292(6):E1607–E1615. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00512.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reszko AE, Kasumov T, Pierce BA, David F, Hoppel CL, Stanley WC, Des RC, Brunengraber H. Assessing the reversibility of the anaplerotic reactions of the propionyl-CoA pathway in heart and liver. J.Biol.Chem. 2003;278(37):34959–34965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selak MA, Armour SM, MacKenzie ED, Boulahbel H, Watson DG, Mansfield KD, Pan Y, Simon MC, Thompson CB, Gottlieb E. Succinate links TCA cycle dysfunction to oncogenesis by inhibiting HIF-alpha prolyl hydroxylase. Cancer Cell. 2005;7(1):77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. Hydroxylation of HIF-1: oxygen sensing at the molecular level. Physiology.(Bethesda.) 2004:19176–19182. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00001.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims NR, Heward SL. Delayed treatment with 1,3-butanediol reduces loss of CA1 neurons in the hippocampus of rats following brief forebrain ischemia. Brain Res. 1994;662(1–2):216–222. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90815-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slevin M, Kumar P, Gaffney J, Kumar S, Krupinski J. Can angiogenesis be exploited to improve stroke outcome? Mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;111(3):171–183. doi: 10.1042/CS20060049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soucek T, Cumming R, Dargusch R, Maher P, Schubert D. The regulation of glucose metabolism by HIF-1 mediates a neuroprotective response to amyloid beta peptide. Neuron. 2003;39(1):43–56. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00367-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PG, Rippy NA, Dorenbos K, Concepcion RC, Agarwal AK, Rho JM. The ketogenic diet increases mitochondrial uncoupling protein levels and activity. Ann.Neurol. 2004;55(4):576–580. doi: 10.1002/ana.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki M, Suzuki M, Kitamura Y, Mori S, Sato K, Dohi S, Sato T, Matsuura A, Hiraide A. Beta-hydroxybutyrate, a cerebral function improving agent, protects rat brain against ischemic damage caused by permanent and transient focal cerebral ischemia. Jpn.J Pharmacol. 2002;89(1):36–43. doi: 10.1254/jjp.89.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson R, Sharpe F. Infarct measurement methodology. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1994:14697–14698. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1994.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda K. Role of hyperglycemia and glutamate receptors in ischemic injury in acute cerebral infarction. Stroke. 2006;37(9):2199. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000237184.30021.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto Y. Cell death regulation by the Bcl-2 protein family in the mitochondria. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195(2):158–167. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veech RL. The therapeutic implications of ketone bodies: the effects of ketone bodies in pathological conditions: ketosis, ketogenic diet, redox states, insulin resistance, and mitochondrial metabolism. Prostaglandins Leukot.Essent.Fatty Acids. 2004;70(3):309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LW, Kasumov T, Yu L, Jobbins KA, David F, Previs SF, Kelleher JK, Brunengraber H. Metabolomic assays of the concentration and mass isotopomer distribution of gluconeogenic and citric acid cycle intermediates. Metabolomics. 2006;2(2):85–94. [Google Scholar]

- Yudkoff M, Daikhin Y, Melo TM, Nissim I, Sonnewald U, Nissim I. The ketogenic diet and brain metabolism of amino acids: relationship to the anticonvulsant effect. Annu.Rev Nutr. 2007:27415–27430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Lange DJ, Voustianiouk A, MacGrogan D, Ho L, Suh J, Humala N, Thiyagarajan M, Wang J, Pasinetti GM. A ketogenic diet as a potential novel therapeutic intervention in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. BMC.Neurosci. 2006:729. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Our schema of the neuroprotective properties of ketone bodies relates ketone body metabolism to the stabilization of HIF-1α through product inhibition of prolyl hydoxylase (PHD) by succinate as follows: the fate of glucose (via glycolysis) and ketone bodies (acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate; AcAc, BHB) in brain mitochondria enter the citric acid cycle as acetyl-CoA residues and through a condensation reaction with oxaloacetate, catalyzed by citrate synthase, form citrate. Succinate is generated by the catabolism of acetyl-CoA via the citric acid cycle and through the activation of AcAc to AcAc-CoA via the enzyme succinyl-CoA-acetoacetate-CoA transferase (β-oxoacid-CoA-transferase). Activation of AcAc to AcAc-CoA requires succinyl-CoA as CoA donor and the resultant product is succinate. The proposed mechanism for the stabilization of HIF-α is shown to occur through the accumulation of mitochondrial succinate. With ketone body utilization mitochondrial succinate is elevated; maintaining the succinate mitochondrial pool would require transport of succinate out of the mitochondria via dicarboxylic acid transporter system into the cytosol. Elevation of succinate in the cytosol results in stabilization of HIF-1α through the product inhibition of PHD. During conditions when succinate does not accumulate, PHD is the enzyme which catalyzes the reaction of HIF-1α to the hydroxylated form (OH-HIF-1α) and undergoes proteasome degradation. Hydroxylation also requires 2-oxoglutarate* as a substrate and generates succinate as a co-product. The resultant increase in HIF-1α stimulates the production of a vasogenic activator (VEGF), erythropoietin and survival pathways, through the activation of related target genes, including Bcl-2. (Note the nomenclature for 2-oxoglutarate*, also known 2-ketoglutarate, refers to the cytosolic substrate, whereas 2-ketoglutarate notation in the citric acid cycle refers to the mitochondrial substrate).