Abstract

Objectives:

To assess the periodontal status among the patients suffering from acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and to investigate whether periodontitis is a risk factor for AMI or not.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study of 60 subjects, 30 subjects in each AMI group and control group was conducted. Details of risk factors like age, sex, smoking, and alcohol consumption were obtained through a personal interview. Medical history was retrieved from the medical file. The oral hygiene status was assessed by using a simplified oral hygiene index (OHI-S) and the periodontal status was assessed by community periodontal index (CPI) and loss of attachment (LOA) as per World Health Organization (WHO) methodology 1997. Chi-square test was used to analyze qualitative data whereas t-test and one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was used for quantitative data. Multiple regression model was applied to check the risk factors for AMI.

Results:

The mean OHI-S score for case and control group was 3.98 ± 0.70 and 3.11 ± 0.68, respectively, which was statistically highly significant ( P < 0.001). There was high severity of periodontitis (for both in terms of CPI and LOA) in the case group as compared with control group, that was found to be statistically highly significant ( P < 0.001). There was a significant result for OHI-S and LOA score with odds ratio of 0.13 and 0.79, respectively, when the multiple logistic regression model was applied.

Conclusion:

The results of the present study show evidence that those patients who have experienced myocardial infarction exhibit poor periodontal conditions in comparison to healthy subjects and suggest an association between chronic oral infections and myocardial infarction.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction, oral hygiene, periodontal disease, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease (CVD) are widespread conditions and therefore, an association between them is an important scientific subject from a preventive point of view. Several studies have been conducted using cohort, cross-sectional, or case control designs with varying conclusions on the strength of the association.[1] However, some studies[2–4] did not confirm such associations. There may be various reasons for this inconsistency, such as the use of different diagnostic criteria for periodontitis [e.g., the Community periodontal index of treatment needs (CPITN), the Russell′s periodontal index and probing depth (PD)] and different considerations of CVD risk factors. Secondly, host factors regulating inflammatory immune response, which have been identified in both diseases, might influence the interaction between CVD and periodontal disease. Finally, the impact of periodontal pathogens on the relationship between CVD and periodontitis has only been included in recent articles.[5]

Periodontitis shares a series of risk factors with CVD, such as a higher incidence in adult males, smokers, diabetics, and individuals with stress and/or a low socio-economic level. According to the most widely established hypothesis, the relationship between AMI and periodontitis depends on risk factors common to both diseases,[6] with tobacco use as the main confounding factor.[7]

Other hypotheses point to the direct action of periodontal pathogens that produce endotoxins and the release of pro-inflammatory mediators by the host monocytes, causing local and systemic destruction of the connective tissue,[8] favoring platelet aggregation and thromboembolic events.[9] It has even been proposed that these periodontal pathogens or their lipopolysaccharides are systemically disseminated via the blood flow and directly infect the vascular endothelium, producing an atherosclerotic lesion and subsequent myocardial ischemia.[10] Lipopolysaccharides that pass to the blood, along the side of inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) or interleukin1β, can induce secretion in the liver of acute-phase proteins, such as C-reactive protein. These proteins can form deposits in the damaged blood vessels, with the consequent activation of phagocytes and release of nitrous oxide, contributing to the formation of atheromas.[11]

Two available meta-analyses[12,13] indicate significant heterogeneity in the association between periodontal disease and AMI, suggesting the need for further studies in different populations. Hence, the present study was designed to assess the periodontal status among the patients having AMI and to determine whether periodontitis is a risk factor for the AMI or not.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects

The cross-sectional study was conducted among two groups: Patients with AMI (case group) and healthy control subjects (control group) attending V.S. General Hospital, Ahmedabad. The healthy control group comprised of age-and gender-matched subjects, who had no known systemic disease or condition and used no medication at that time of examination. These subjects were the relatives of the patients with AMI admitted into V.S. General Hospital. The criterion for inclusion as a case was the presence of a history of AMI verified by characteristic electrocardiogram changes and elevation of serum troponin I (TnI) level. The diagnosis of ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) was made if there was ST segment elevation of 2 mm or more in precordial leads or 1mm or more in limb leads and non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) was diagnosed if there was ST depression and/or T wave inversion combined with typical rise of TnI levels according to local laboratory standards. Both patients with STEMI and NSTEMI were included in the study and had undergone a through oral examination after four days of hospitalization when all were free of anticoagulation therapy.

A total of 30 subjects in each group; 21 (70%) male and 9 (30%) female subjects were included in the study. The mean ages were 54.3 ± 11.01 years and 53.07 ± 10.53 years for AMI and control group, respectively. All participants gave informed consent to participate in the present study, which was approved by the ethical committee of Ahmedabad Dental College and Hospital, Gujarat, India.

Clinical examination and indices

The periodontal examination of the subjects was done at the V.S. General Hospital, Ahmedabad. The personal details like adverse habits, past history were obtained through personal interview. The medical data were retrieved from the patient files. All periodontal examinations were done by the two trained dentists (MGN and JJ). The examiners could not be “blinded” to the subject's general condition, since they were examined in a hospital. The examiners had been calibrated for periodontal assessment by a senior (PSM). The clinical examination was carried out in artificial light with the use of a plane mouth mirror and World Health Organization (WHO) periodontal probe.

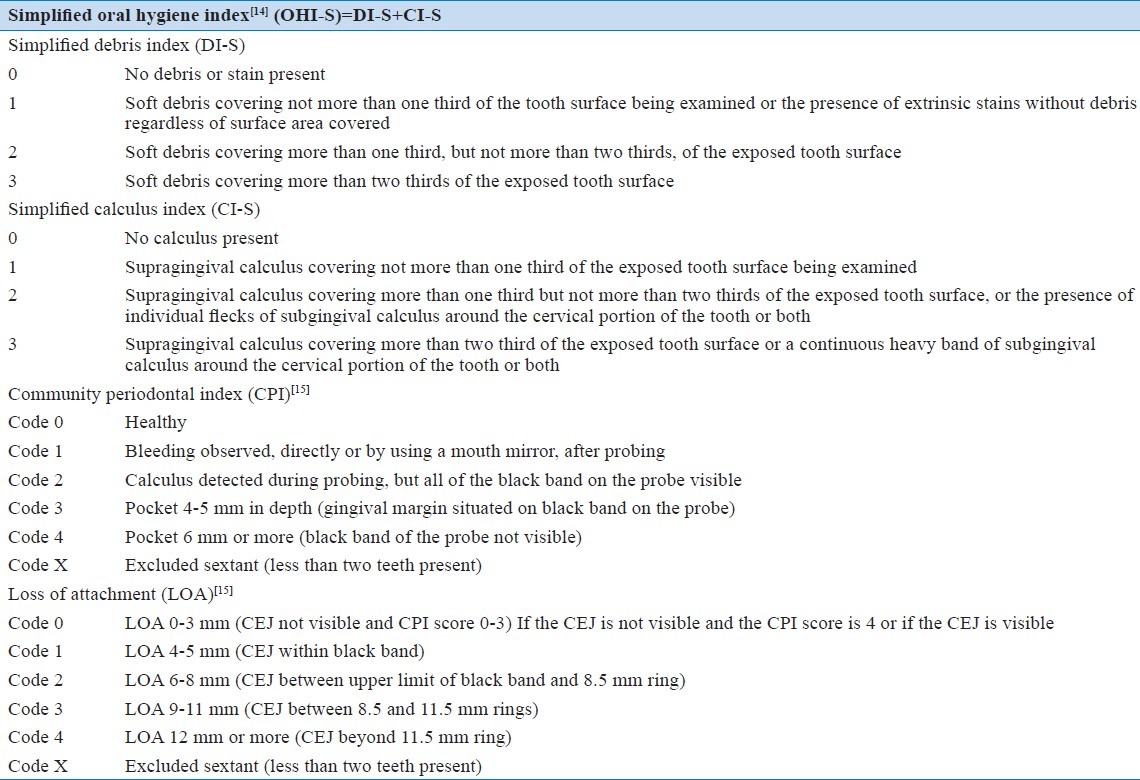

After explaining the study design to the participants, the oral hygiene status was assessed by simplified oral hygiene index (OHI-S)[14] on six indexed teeth (16-upper right posterior first molar, 11-upper right central incisor, 26-upper left posterior first molar, 36-lower left posterior first molar, 31-lower left central incisor, and 46-lower right posterior first molar) and the periodontal status was assessed by CPI and LOA as per WHO methodology 1997,[15] the same indexed teeth were examined. The description of dental indices is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of various dental indices used in the study

Data analysis

Student's t-test was used to analyze the difference between the means of the two groups regarding clinical parameters (oral hygiene status). The Chi-square test was used to analyze difference between the proportions of the two groups. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine the difference in clinical parameters (periodontal status) among the groups. The tests were two-sided, and P values <0.05 were considered significant. Multiple logistic regression analysis was applied to establish possible confounding variables such as age, gender, smoking, body mass index (BMI), hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Periodontitis, collapsed into two categories (absent or mild vs. moderate or severe) to achieve reasonably narrow confidence intervals, was also forced into the model to represent periodontal disease. Data were analyzed using SPSS statistical package version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).[16]

RESULTS

Oral hygiene status (OHI-S)

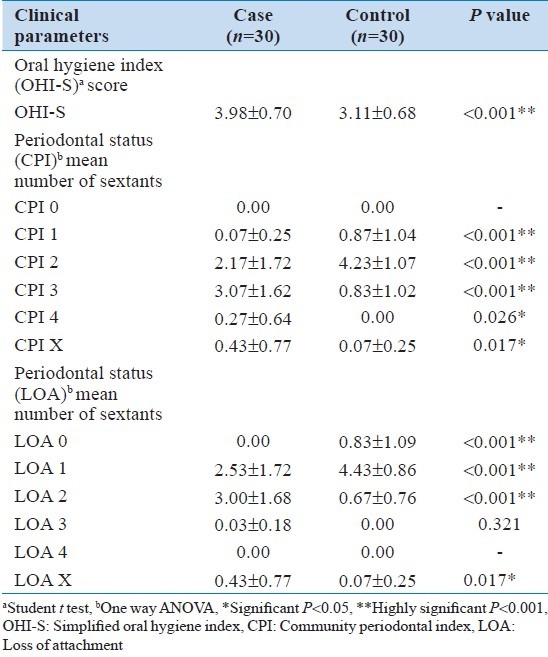

The mean score of OHI-S for the case group was 3.98 ± 0.70 whereas that of control group was 3.11 ± 0.68. The difference between the mean score of these groups was found to be highly significant statistically (P < 0.001) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparisons of clinical parameters between case and control groups

Periodontal status (CPI and LOA)

Table 2 shows the mean CPI and LOA score for both the case and the control group. There was statistically highly significant difference (P < 0.001) when the mean scores for CPI 1, CPI 2, CPI 3 and CPI X were compared among case and control groups. Whereas for score CPI 4, the difference was found to be significant statistically (P < 0.05). Similarly, there was statistically highly significant difference (P< 0.001) when the mean scores for LOA 0, LOA 1, LOA 2 and LOA X were compared among case and control groups. However, no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) was observed when the mean scores for LOA 3 were compared between the two groups.

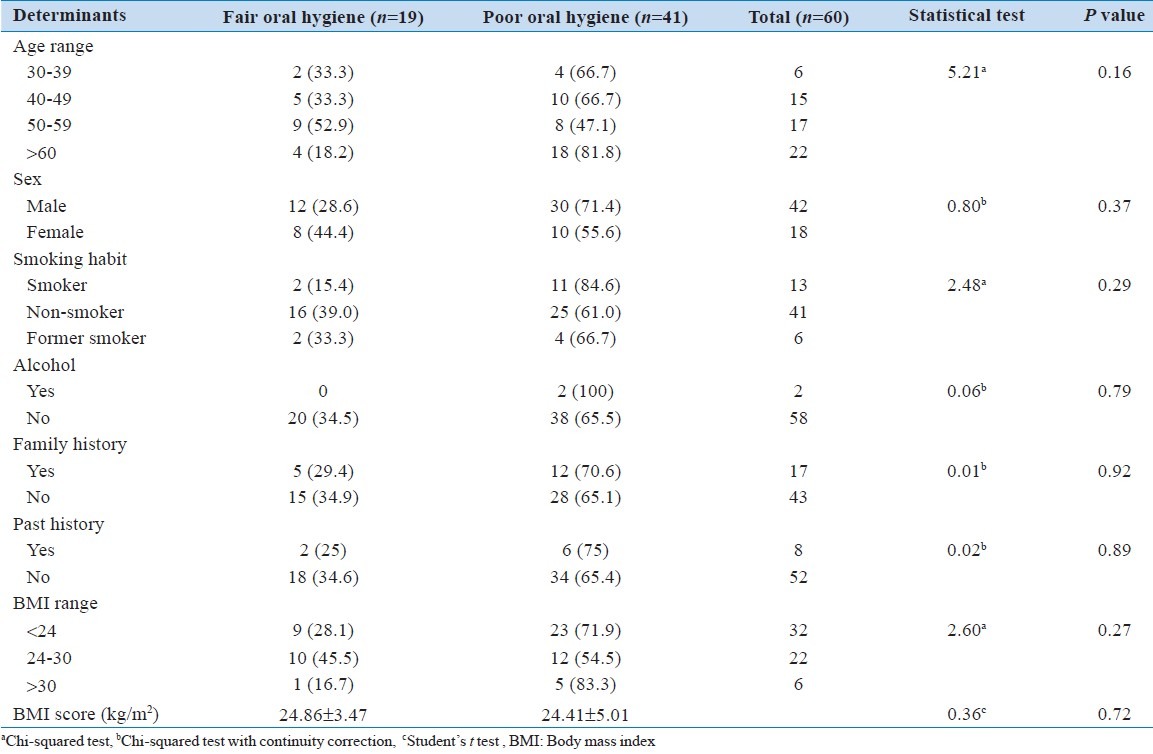

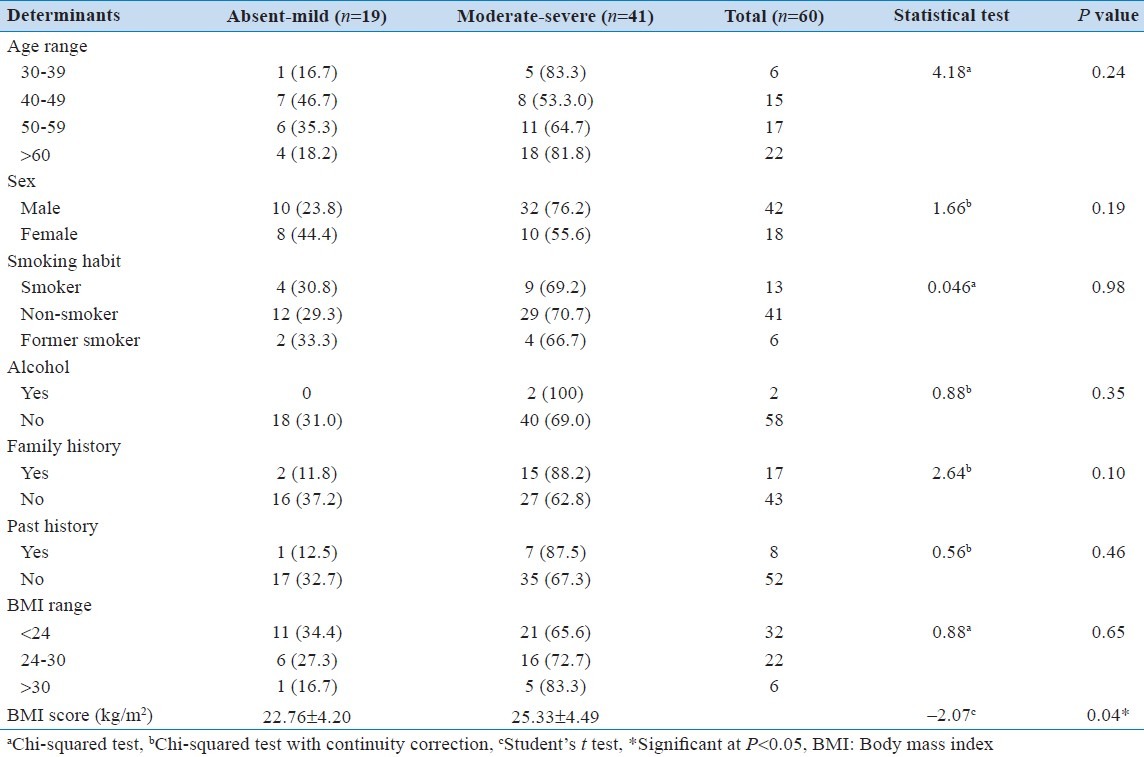

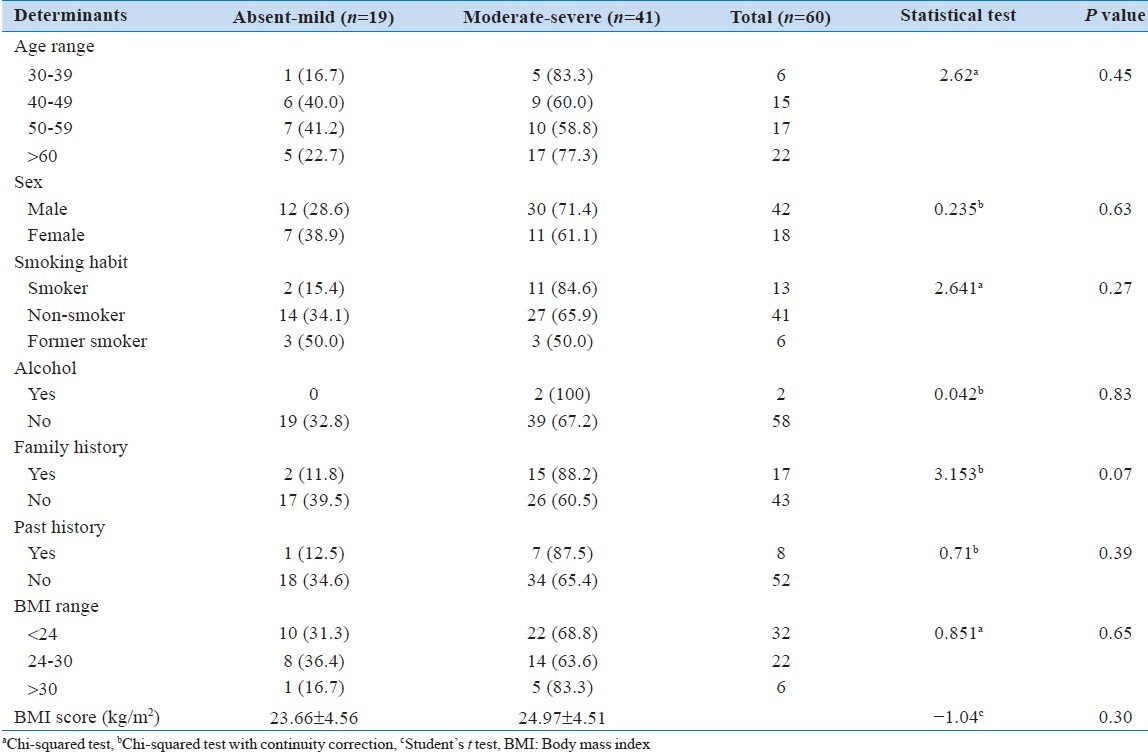

The association between the OHI-S score, CPI score and LOA score with the risk factors of AMI is shown in Tables 3 to 5 respectively. There was no statistically significant difference ( P > 0.05) found between the clinical parameters and the risk factors (age, gender, smoking, alcohol) of AMI. The oral hygiene and the periodontal condition worsened as the age advanced, however, there was no significant difference found ( P > 0.05). The male subjects were more prone to periodontitis as compared to their female counterparts, but it does not reach to a significant level. The only significant difference was observed when the mean BMI scores were compared for the (P = 0.04).

Table 3.

Associations between oral hygiene simplified oral hygiene index (OHI-S score) and very well.known risk factors for acute myocardial infarction

Table 5.

Associations between periodontitis loss of attachment (loss of attachment score) and very well.known risk factors for acute myocardial infarction

Table 4.

Associations between periodontitis community periodontal index (community periodontal index score) and very well.known risk factors for acute myocardial infarction

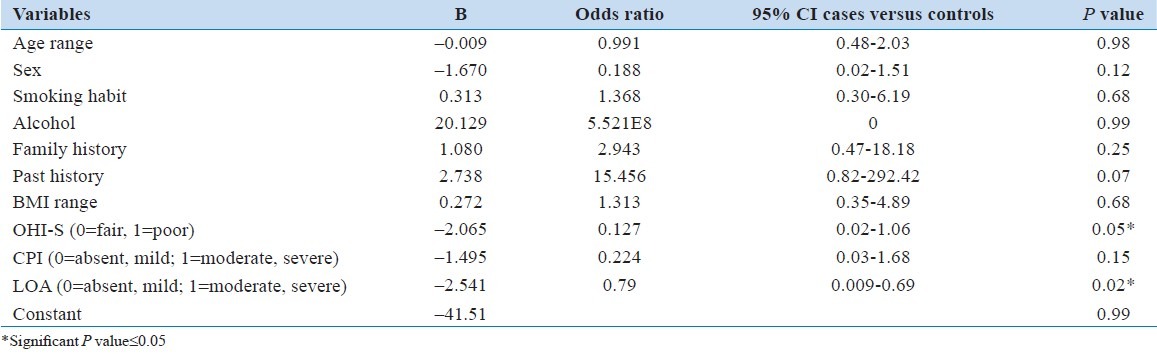

The multiple logistic regression analysis [Table 6] was done to remove the confounding effects of various factors revealed that oral hygiene (OR = 0.13, CI = 0.02-1.06) and LOA score (OR = 0.79, CI = 0.009-0.69) were the significant independent predictors of AMI. These results suggest that poor oral hygiene and poor periodontal status slightly increased the risk for AMI.

Table 6.

Logistic regression model for study variables and acute myocardial infarction

Age, gender, adverse oral habits (smoking and alcohol), past medical history, BMI, and family history of AMI ceased to act as independent predictors of AMI after indirect standardization through the multiple logistic regression analysis.

DISCUSSION

The present study constituted 60 study subjects, of which 30 were patients suffering from AMI and 30 belonged to the control group. The AMI group was matched with the control group in age and gender. The relatives of the patients having AMI formed the control group. This approach is clinically justified in relation to the specific population of AMI patients, and more likely to be reliable in view of their unusual accumulation of risk factors for periodontal disease.

Various studies state that age is a risk factor for both AMI as well as periodontal diseases.[5,17,18] The mean age of the AMI patients in the present study was 54.3 ± 11.01 years, which was found to be lower than the subjects of Rutger, et al.,[17] Cueto, et al.,[18] Willerhausen, et al.[19] The mean age of the AMI patients in the present study was higher than the subjects of Stein, et al.5] and Rai, et al. [20] This might be because different age ranges were selected in the different studies. This reflects that the AMI is prevalent in wider range of the age groups. Hence, it has become a priority to detect such patients at different age groups so that the risk involving its oral complications can be prevented as well.

The oral hygiene status of the case group was significantly poor as compared to the control group in the present study. Scannapieco, et al., reported that poor oral hygiene is associated with many systemic diseases, one of which is myocardial infarction.[21] Karhunen, et al., stated that low oral hygiene was related to an increased risk of sudden cardiac death.[22] Through extensive literature review, it was concluded that there was no similar study related to AMI and oral hygiene, thus more studies are required on these subjects.

The clinical periodontal findings like mean periodontal pocket depth, mean LOA and the number of sextants having bleeding were significantly higher than in controls. This was in accordance with the previous studies of similar[5,23] or different[17,18,24] design to the present work. The oral hygiene and the periodontal health shows the worsening of the score in the patients with AMI due to their part stay in intensive care unit and a longer hospital stay.[5] Furthermore, AMI patients usually receive anticoagulant drug treatment, which can increase the gingival bleeding.[18]

Higher prevalence and increased severity of the periodontal disease in patients with AMI was in accordance to the results of the previous studies.[25,26] This issue might be of importance because a higher number and increased depths of periodontal pockets favor the colonization of pathogens resulting in a greater risk of bacteremia.[2] Advanced periodontitis probably implies a sufficiently long evolution of the disease to become a risk factor for coronary artery disease. Severe periodontitis has been reported to be associated with a greater thickness of the muscle layer of coronary artery supporting the role played by the pathogenesis of periodontitis in the formation of atheroma and subsequent AMI.[27]

The multiple logistic regressions showed that oral hygiene and LOA were significantly associated with AMI. However, the risk factors like age, sex, smoking, alcohol, family history, and BMI are not significantly associated with AMI. This result was in contrast with the previous studies.[5,17,18] Studies related to AMI and periodontitis have been published with most ambiguous results with odds ratios of associations varying between 0.9 and 3.2.[8,13,28] The reasons for such diverse findings or lack of associations may solely reflect inadequate definition of periodontitis. It may also reflect study design not accounting for proper control subjects. In the present study, a significant effort was made to enroll carefully matched control subjects.

Research work conducted by Armitage,[11] Rutger, et al., [17] and Mattila, et al.[24] shows there exist an association between AMI and periodontal disease. The periodontal status among the subjects was assessed by using CPI and LOA index as per the WHO methodology 1997.[15] Extensive literature reviews showed that very few studies were conducted to assess the periodontal status by using WHO methodology 1997. This fact implies that the important, but so far understudied issue of prevalence and severity of periodontitis in AMI patients requires a standardized approach.

The limitations of this study include its performance in one hospital and relatively on a small sample, but comparable with most of the previous studies, this may not be large enough to represent the AMI population. In the present study, radiographs were not used, and periodontitis was defined with clinical measurements. Although reproducibility might be better appreciated in radiographic diagnostics, periodontal bone loss in radiographs can be detected in patients with untreated periodontitis, as well as in patients with a history of periodontitis. Moreover, in this study, partial mouth recordings protocol was used for the estimation of periodontal diseases that may be accurate and efficient in estimating the mean periodontal measures but could severely under and/or over-estimate the prevalence of periodontal disease.

Within the limits of the present study, the two main conclusions can be drawn: (1) the results demonstrate a worsening of the periodontal status in patients with AMI compared to healthy controls; (2) among the different cut-off values, oral hygiene and LOA showed the discrepancy between the patients with AMI and the control subjects. The results of the present study show that there is a strong association between periodontal health and AMI. However, to help break potentially confounded associations, larger and better controlled studies involving socially homogenous populations which can establish causality and which can estimate specific periodontal pathogens are required.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Holmstrup P, Poulsen AH, Andersen L, Skuldbøl T, Fiehn NE. Oral infections and systemic diseases. Dent Clin North Am. 2003;47:575–98. doi: 10.1016/s0011-8532(03)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hujoel PP, Drangsholt M, Spiekerman C, Derouen TA. Examining the link between coronary heart disease and the elimination of chronic dental infections. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:883–9. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howell TH, Ridker PM, Ajani UA, Hennekens CH, Christen WG. Periodontal disease and risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease in U.S. male physicians. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:445–50. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)01130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuominen R, Reunanen A, Paunio M, Paunio I, Aromaa A. Oral health indicators poorly predict coronary heart disease deaths. J Dent Res. 2003;82:713–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stein JM, Kuch B, Conrads G, Fickl S, Chrobot J, Schulz S, et al. Clinical periodontal and microbiologic parameters in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1581–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Syrjänen J. Vascular diseases and oral infections. J Clin Periodontol. 1990;17:497–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.1992.tb01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Müller HP. Periodontitis and cardiovascular disease: An ecological fallacy? Eur J Oral Sci. 2001;109:286–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2001.00109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck J, Garcia R, Heiss G, Vokonas PS, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1123–37. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herzberg MC, Weyer MW. Dental plaque, platelets, and cardiovascular diseases. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:151–60. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross R. Atherosclerosis – An inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armitage GC. Periodontal infections and cardiovascular disease – How strong is the association? Oral Dis. 2000;6:335–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2000.tb00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Janket SJ, Baird AE, Chuang SK, Jones JA. Meta-analysis of periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:559–69. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madianos PN, Bobetsis GA, Kinane DF. Is periodontitis associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease and preterm and/or low birth weight births? J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:22–36. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.29.s3.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greene JC, Vermillion JR. The simplified oral hygiene index. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;68:7–13. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1964.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization,Geneva. 4th ed. Delhi: AITBS Publisher and Distributors; 1997. Oral health survey basic methods; pp. 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chicago IL:: SPSS Inc; 2008. Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 17. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rutger PG, Ohlsson O, Pettersson T, Renvert S. Chronic periodontitis, a significant relationship with acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:2108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cueto A, Mesa F, Bravo M, Ocaña-Riola R. Periodontitis as risk factor for acute myocardial infarction.A case control study of Spanish adults. J Periodontal Res. 2005;40:36–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2004.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willershausen B, Kasaj A, Willershausen I, Zahorka D, Briseño B, Blettner M, et al. Association between chronic dental infection and acute myocardial infarction. J Endod. 2009;35:626–30. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rai B, Kaur J, Jain RK, Anand SC. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease. JK Sci. 2009;11:194–5. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scannapieco FA, Dasanayake AP, Chhun N. “Does periodontal therapy reduce the risk for systemic diseases”? Dent Clin North Am. 2010;54:163–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karhunen V, Forss H, Goebeler S, Huhtala H, Ilveskoski E, Kajander O, et al. Radiographic assessment of dental health in middle-aged men following sudden cardiac death. J Dent Res. 2006;85:89–93. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vijayalakshmi R, Anitha S, Emmadi P, Ambalavanan N, Ramarishnan T, Saravankumar R. Association between periodontal disease and acute myocardial infarction. J Ind Assoc Public Health Dent. 2007;10:101–6. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mattila KJ, Nieminen MS, Valtonen VV, Rasi VP, Kesäniemi YA, Syrjälä SL, et al. Association between dental health and acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1989;298:779–81. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6676.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emingil G, Buduneli E, Aliyev A, Akilli A, Atilla G. Association between periodontal disease and acute myocardial infarction. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1882–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.12.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nonnenmacher C, Stelzel M, Susin C, Sattler AM, Schaefer JR, Maisch B, et al. Periodontal microbiota in patients with coronary artery disease measured by real-time polymerase chain reaction: A case-control study. J Periodontol. 2007;78:1724–30. doi: 10.1902/jop.2007.060345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zamirian M, Raoofi S, Javanmardi R. Relationship between periodontal disease and acute myocardial infarction. Iran Cardiovasc Res J. 2008;1:216–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joshipura KJ, Rimm EB, Douglass CW, Trichopoulos D, Ascherio A, Willett WC. Poor oral health and coronary heart disease. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1631–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750090301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]