Abstract

We report a case of 68-year-old Caucasian man who presented with cerebral infarcts secondary to arterial thrombosis associated with nephrotic syndrome. His initial presentation included edema of legs, left hemiparesis, and right-sided cerebellar signs. Investigations with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of brain showed multiple cerebral infarcts in middle cerebral and posterior cerebral artery territory. Blood and urine investigations also showed impaired renal function, hypercholesterolemia, hypoalbuminaemia, and nephrotic range proteinuria. Renal biopsy showed minimal change disease. Cerebral infarcts were treated with antiplatelet agents and nephrotic syndrome was treated with high dose steroids. Patient responded well to the treatment and is all well till date.

Keywords: Arterial thrombosis, cerebral infarction, nephrotic syndrome

Introduction

Nephrotic syndrome is known to cause hypercoaguable state. As Pierre Rayer first reported renal vein thrombosis associated with nephrotic syndrome in 1837, thrombosis is known to be one of the main complications of nephrotic syndrome with the renal vein being the most frequent site.[1–5] Awareness of pathogenesis and assessment of the risk factors for arterial thrombosis are required to allow appropriate management of these patients. There are no reliable risk factors to suggest anticoagulation therapy in patients with nephrotic syndrome and prophylactic anticoagulants remain controversial. Our case once again highlights the dilemma in managing these patients; however it also throws some light on management.

Case Report

A 68-year-old retired office manager (male) was admitted to the hospital with worsening epigastric pain, clay colored stools, nausea, and ankle swelling. He also complained of weakness and tingling in left arm, slurred speech and difficulty getting words out. His risk factor for cerebro-vascular disease included only hypertension that was well-controlled with felodipine. On examination, there was non-pitting pedal edema, right-sided cerebellar signs (past pointing, dysdiadochokinesia), left hemiparesis, and expressive dysphasia. Blood pressure was 180/90 mmHg. Urine Dipstick had 2+ blood, 4+ protein with urinary Protein creatinine ratio of 1401 (approx. 14 g/day). Renal function was mildly impaired with creatinine at 168 μmol/L. Albumin was low at 16 g/L. Cholesterol was elevated at 13.8 mmol/L.

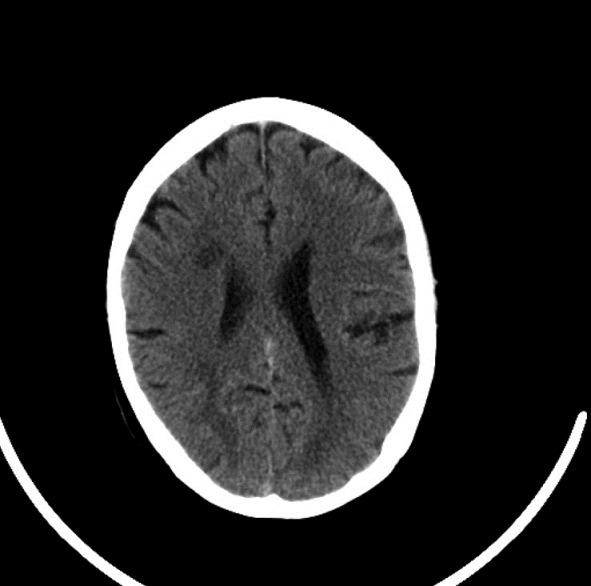

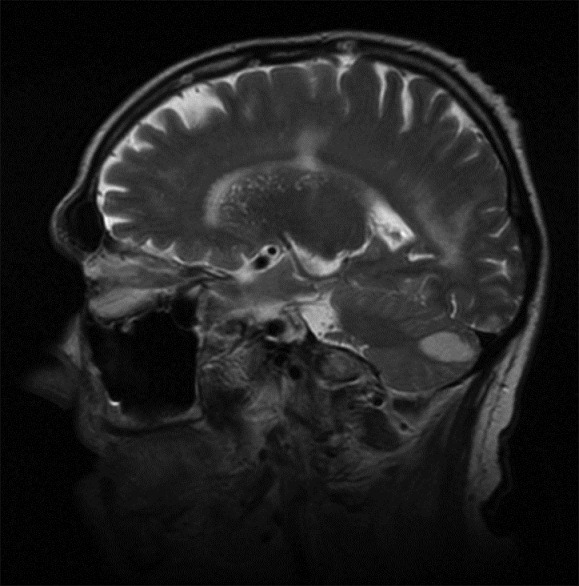

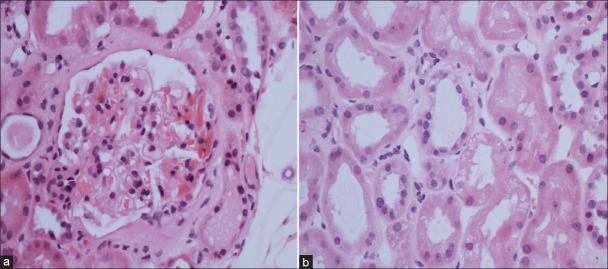

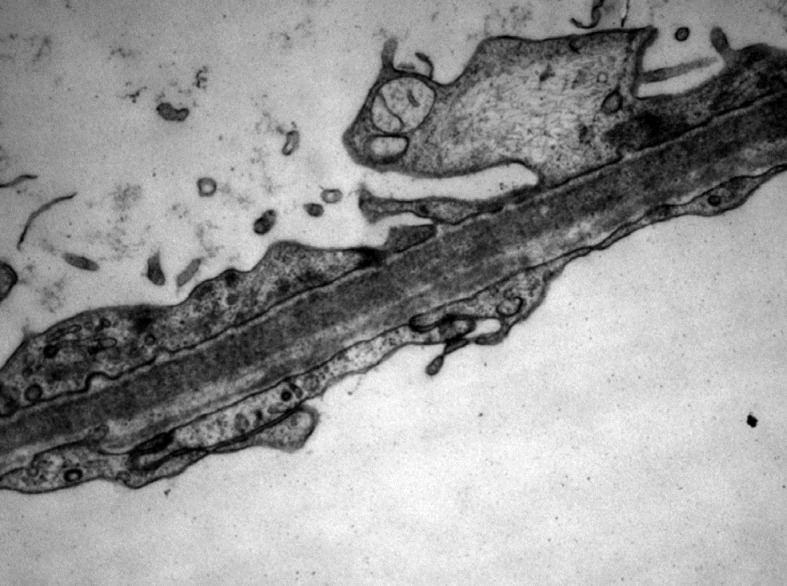

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed widespread cerebral infarcts in the middle cerebral and posterior cerebral artery territory [Figures 1 and 2]. Transthoracic echocardiogram and carotid doppler did not show any abnormality. Renal biopsy showed minimal change disease [Figures 3–5]. Auto immune profile and compliments were normal. Immunoelectrophoresis did not show any plasma cell dyscrasia. Protein C and S levels were at lower end of normal range that was considered secondary to renal loss rather than primary deficiency.

Figure 1.

CT of brain showing infarcts in middle cerebral artery infarcts

Figure 2.

MRI of brain showing cerebellar infarct

Figure 3.

Haematoxylin and eosin stain: (a) shows normal glomerulus. (b) shows vacuolated renal tubular cells suggesting heavy proteinuria and uptake of albumin by cells

Figure 5.

Electron Microscopy of glomerulus showing flattening of podocyte foot processes

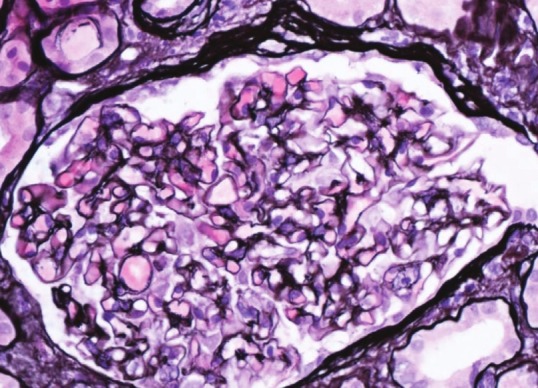

Figure 4.

Siver stain of glomerulus showing normal basement membrane

Other investigations for hypercoagulable state such as anti-cardiolipin antibodies, factor V leiden mutation were within normal limits.

Contrast CT of chest/abdomen/pelvis looking for malignancy was within normal limits.

Infarcts were considered secondary to arterial thombosis as a result of hypercoagulable state seen in nephrotic syndrome. Patient was treated with antiplatelet agents like aspirin and clopidogrel. Patient did not receive any prophylactic or therapeutic anticoagulation with heparin or low molecular weight heparin during his hospital stay. Nephrotic syndrome was treated with three doses of intravenous methyl prednisone and was started on oral prednisone at 1 mg/kg that was tapered down over a period of 3 months. There was good response to treatment with resolution of proteinuria and improvement in renal function. Most recent albumin has come up to 36 g/L. Patient remains in remission till date and has not had any further thrombotic episode.

Discussion

Nephrotic syndrome is one of the secondary causes of hypercoaguable state.[6–8] Hypercoagulable state can be either primary or secondary. Primary causes are due to deficiencies of anti-thrombin III, protein C or protein S. Other secondary causes include: Malignancy, pregnancy, and oral contraceptive use. Thrombotic complications in patients with nephrotic syndrome occur in both venous and arterial systems, with the most common being renal vein thrombosis.[2] In adults, the majority of thromboses are venous and arterial thromboses are more common in children.[3] Review of literature shows that hypercoagulable state is greater in nephrotic syndrome secondary to membranous nephropathy.[7] In our case, the etiology was minimal change disease. There are no data on the absolute risk of development of thromboembolism, but an observational study shows the risk of vascular thrombosis is greatest within the first 6 months of diagnosis, with an annual incidence rate of 1.48% for arterial thromboembolism.[9] Cerebral infarction in nephrotic syndrome is rare and has been previously reported in very few cases. Marsh et al.[10] described two adult patients, 34 and 36 years of age, who presented with acute cerebral infarction and were found to have a hypercoagulable state due to nephrotic syndrome. Although it is not clear why nephrotic syndrome causes a hypercoagulable state, there have been many hypothesis for its mechanism, such as urinary loss of antithrombin III,[4] Factor XII deficiency,[11] protein C, and protein S deficiency,[12] increased platelet aggregation, and increased hepatic production clotting factors.[13–16] Most authors report increased fibrinogen levels. Some studies described an increased incidence of thrombotic complications and hypercoagulation during steroid treatment.[9] Hypercholesterolemia may be another contributing factor in nephrotic patients.

Arterial thombosis is diagnosed with CT or MRI. Investigations for etiology of nephrotic syndrome involve autoimmune screen and renal biopsy. Treatment of arterial thrombosis involves anticoagulation with either conventional heparin or low molecular weight heparin or warfarin. Cerebral infarcts are treated with antiplatelet agents as in any other ischemic stroke. Prophylactic anticoagulation in patients with nephrotic syndrome and cerebral infarcts is unclear, and we did not give any prophylaxis in our patient.[17] Treatment of nephrotic syndrome involves general measures such as treating hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, proteinuria with angiotensin inhibiters, and edema with salt restriction and diuretics. Specific treatment of nephrotic syndrome involves immunosuppression with either steroids and antimetabolites or biological agents.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Llach F. Hypercoagulability, renal vein thrombosis, and other thrombotic complications of nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int. 1985;28:429–39. doi: 10.1038/ki.1985.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cameron JS. The nephrotic syndrome and its complications. Am J Kidney Dis. 1987;10:157–71. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(87)80170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kendall AG, Lohmann RC, Dossetor JB. Nephrotic syndrome: A hypercoagulable state. Arch Intern Med. 1971;127:1021–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller RB, Harrington JT, Ramos CP, Relman AS, Schwartz WB. Long-term results of steroid therapy in adults with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Am J Med. 1969;46:919–29. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(69)90094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marsh EE, 3rd, Biller J, Adams HP, Jr, Kaplan JM. Cerebral infarction in patients with nephrotic syndrome. Stroke. 1991;22:90–3. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parag KB, Somers SR, Seedat YK, Byrne S, Da Cruz CM, Kenoyer G. Arterial thrombosis in nephrotic syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1990;15:176–7. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80516-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuh JL, Teng MM, Yang WC, Liu HC. Cerebral infarction in young men with nephrotic. Stroke. 1992;23:295–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner BM, Rector FC. The Kidney. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1991. p. 1858. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahmoodi BK, ten Kate MK, Waanders F, Veeger NJ, Brouwer JL, Vogt L, et al. High absolute risks and predictors of venous and arterial thromboembolic events in patients with nephrotic syndrome: Results from a large retrospective cohort study. Circulation. 2008;117:224–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.716951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanfer A, Kleinknecht D, Broyer M, Josso F. Coagulation studies in 45 cases of nephrotic syndrome without uremia. Thromb Diath Haemorrh. 1970;24:562–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vigano-D’Angelo S, D’Angelo A, Kaufman CE, Jr, Sholer C, Esmon CT, Comp PC. Protein S deficiency occurs in the nephrotic syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:42–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-107-1-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mukherjee AP, Toh BH, Chan GL, Lau KS, White JC. Vascular complications in nephrotic syndrome: Relationship to steroid therapy and accelerated thromboplastin generation. Br Med J. 1970;4:273–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.4.5730.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schafer AI. The hypercoagulable states. Ann Intern Med. 1985;102:814–28. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-102-6-814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panicucci F, Sagripanti A, Vispi M, Pinori E, Lecchini L, Barsotti G, et al. Comprehensive study of haemostasis in nephrotic syndrome. Nephron. 1983;33:9–13. doi: 10.1159/000182895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alkjaersig N, Fletcher AP, Narayanan M, Robson AM. Course and resolution of the coagulopathy in nephrotic children. Kidney Int. 1987;31:772–80. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vaziri ND. Nephrotic syndrome and coagulation and fibrinolytic abnormalities. Am J Nephrol. 1983;3:1–6. doi: 10.1159/000166678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bellomo R, Atkins RC. Membranous nephropathy and thromboembolism: Is prophylactic anticoagulation warranted? Nephron. 1993;63:249–54. doi: 10.1159/000187205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]