Abstract

Osteoporosis, characterized by low bone mass and structural deterioration of bone tissue with an increased susceptibility to fractures, is a major public health threat to the elderly. Bone mass homeostasis in adults is maintained locally by the balance between osteoblastic bone formation and osteoclastic bone resorption. Haploinsufficiency of PPARγ, a key transcription factor implicated previously in adipogenesis, lipid metabolism, and glucose homeostasis, has now been shown to promote osteogenesis through enhanced osteoblast formation. These findings support a reciprocal relationship between the development of bone and fat, and may prompt further exploration of the PPAR pathway as a potential target for intervention in osteoporosis.

Osteoclast and osteoblast: the yin and yang that control skeletal homeostasis

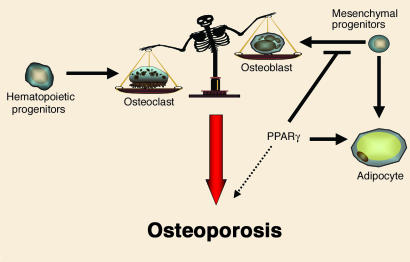

In vertebrates, bones undergo a process of continual renewal throughout life. This process, called bone remodeling, can be viewed as a balance between osteoblast-mediated bone formation and osteoclast-mediated bone resorption (1). Osteoclasts are specialized cells derived from the monocyte/macrophage lineage that degrade extracellular bone matrix (2). On the other hand, mesenchyme-derived osteoblasts rebuild the resorbed bone by elaborating matrix that subsequently undergoes mineralization (3). An imbalance between the two arms of bone remodeling is associated with diseases including rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis (Figure 1). According to the National Institutes of Health and the National Osteoporosis Foundation, in the US alone, 10 million individuals have osteoporosis, and almost 34 million more have low bone mass, placing them at increased risk for osteoporosis.

Figure 1.

Model for the influence of the PPARγ pathway on osteogenesis. Bone homeostasis is maintained by the balance between osteoblastic bone formation and osteoclastic bone resorption. An imbalance between the two is associated with osteoporosis. The PPARγ pathway not only determines adipocyte differentiation from mesenchymal progenitors, but also inhibits osteoblast differentiation, as revealed by Akune et al. (10). This new finding raises the possibility of interrupting the PPARγ pathway for the treatment of osteoporosis.

PPARγ: adipocyte determinator and osteoblast terminator?

Besides osteoblasts, mesenchymal progenitor cells can also give rise to adipocytes, myocytes, and chondrocytes. The nuclear receptor PPARγ is the dominant regulator of adipogenesis and is required for the expression of many adipocyte genes, including adipocyte-specific fatty acid binding protein, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, and lipoprotein lipase (4). Multiple studies have suggested that a certain degree of plasticity exists within the mesenchymal lineage. For example, myoblastic cell lines can be converted to adipocytes through expression of PPARγ and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α (5); bone morphogenetic protein and retinoic acid cooperate to induce osteoblast differentiation of preadipocytes (6); and ligand activation of PPARγ drives the differentiation of multipotent mesenchymal progenitor cells towards adipocytes over osteoblasts (7, 8). Clinically, the decreased bone mass observed in age-related osteoporosis is accompanied by an increase in marrow adipose tissue (9).

In the current issue of the JCI, Akune et al. further explore the relationship between osteogenesis and adipogenesis using cells and animals deficient in PPARγ expression (10). They showed that homozygous PPARγ-deficient ES cells failed to differentiate into adipocytes but spontaneously differentiated into osteoblasts (Figure 1). Furthermore, PPARγ haploinsufficiency was shown to enhance osteoblastogenesis in vitro and to increase bone mass in mice in vivo. Indeed, several osteoblast markers and key molecules for osteoblast differentiation, including Runx2 and osterix, were more highly expressed in primary cultured marrow cells lacking expression of one PPARγ allele. In contrast to the effect on osteoblasts, Akune et al. found no change in osteoclast function in cells lacking PPARγ. A number of important issues remain to be addressed, however, including the molecular mechanism whereby loss of PPARγ leads to enhanced osteogenesis. For example, what genes regulated by PPARγ are antagonistic to osteoblast differentiation?

PPARγ and osteoporosis: from bench to clinic

Agents currently approved for treatment of osteoporosis act largely by inhibiting bone resorption. These include hormone replacement therapy, calcium and vitamin D supplementation, and bisphosphonate-based drugs (alendronate sodium/Fosamax and risedronate/Actonel) (11). The only exception is the recently approved parathyroid hormone (PTH)-derived peptide Forteo, which can stimulate bone formation. However, significant disadvantages exist for PTH treatment. For example, sustained exposure to elevated PTH levels results in net bone loss, so intermittent exposure by daily injection is necessary (12). New medicines that promote bone formation/osteoblastogenesis with fewer side effects could have great utility in the treatment of osteoporosis.

The findings of Akune et al. suggest that aspects of the PPARγ pathway might be amenable to pharmacologic intervention in osteoporosis (10). One possibility raised by the authors is the use of PPARγ modulators or antagonists. Some support for this idea comes from a recent study that identified 12/15-lipoxygenase as a susceptibility gene for bone mineral density in mice (13). The authors of this study hypothesized that PPARγ may be involved in these effects, since 12/15-lipoxygenase is capable of generating PPARγ ligands from linoleic/arachidonic acids and oxidized LDL (14, 15). However, the use of PPARγ modulators/antagonists for osteoporosis needs to be approached with caution given the critical role of PPARγ in mammalian physiology. Thiazolidinediones, a class of synthetic PPARγ agonists, are currently used to treat type 2 diabetes. The possibility that an antagonist to PPARγ might exacerbate insulin resistance, particularly in susceptible individuals, needs to be carefully considered. In the case of the estrogen receptor, it has been possible to identify compounds that have tissue-specific actions on a nuclear receptor. A bone-selective PPARγ modulator, in this case an antagonist, may be required to exploit PPARγ as a target in osteoporosis.

Footnotes

See the related beginning on page 846.

Nonstandard abbreviation used: parathyroid hormone (PTH).

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Karsenty G, Wagner EF. Reaching a genetic and molecular understanding of skeletal development. Dev. Cell. 2002;2:389–406. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003;423:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature01658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harada S, Rodan GA. Control of osteoblast function and regulation of bone mass. Nature. 2003;423:349–355. doi: 10.1038/nature01660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. Molecular regulation of adipogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2000;16:145–171. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hu E, Tontonoz P, Spiegelman BM. Transdifferentiation of myoblasts by the adipogenic transcription factors PPAR gamma and C/EBP alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:9856–9860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skillington J, Choy L, Derynck R. Bone morphogenetic protein and retinoic acid signaling cooperate to induce osteoblast differentiation of preadipocytes. J. Cell Biol. 2002;159:135–146. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeon MJ, et al. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma inhibits the Runx2-mediated transcription of osteocalcin in osteoblasts. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:23270–23277. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211610200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lecka-Czernik B, et al. Divergent effects of selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma 2 ligands on adipocyte versus osteoblast differentiation. Endocrinology. 2002;143:2376–2384. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.6.8834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meunier P, Aaron J, Edouard C, Vignon G. Osteoporosis and the replacement of cell populations of the marrow by adipose tissue. A quantitative study of 84 iliac bone biopsies. Clin. Orthop. 1971;80:147–154. doi: 10.1097/00003086-197110000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akune T, et al. PPARγ insufficiency enhances osteogenesis through osteoblast formation from bone marrow progenitors. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:846–855. doi:10.1172/JCI200419900. doi: 10.1172/JCI19900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prestwood KM, Pilbeam CC, Raisz LG. Treatment of osteoporosis. Annu. Rev. Med. 1995;46:249–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.46.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg C, Neumeyer K, Kirkpatrick P. Teriparatide. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2003;2:257–258. doi: 10.1038/nrd1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein RF, et al. Regulation of bone mass in mice by the lipoxygenase gene Alox15. Science. 2004;303:229–232. doi: 10.1126/science.1090985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang JT, et al. Interleukin-4–dependent production of PPAR-gamma ligands in macrophages by 12/15-lipoxygenase. Nature. 1999;400:378–382. doi: 10.1038/22572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tontonoz P, Nagy L, Alvarez JG, Thomazy VA, Evans RM. PPARgamma promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation and uptake of oxidized LDL. Cell. 1998;93:241–252. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81575-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]