Abstract

In order to develop predictive markers for a beneficial humoral immune response, we evaluated the in vivo and in vitro response to the pandemic (p)H1N1 vaccine in young and elderly individuals. We measured serum antibody response and associated this with the in vitro B-cell response to the vaccine, measured by activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID). Both responses decrease with age and are significantly correlated. The percentage of switched memory B cells in blood, both before and after vaccination, is decreased with age. The percentage of switched memory B cells at t0 correlates with the hemagglutination inhibition response and therefore, we suggest that this may be used as a predictive marker for B-cell responsiveness. AID induced by CpG before vaccination also predicts the robustness of the vaccine response. Plasmablasts showed a trend to increase after vaccination in young individuals only. This report establishes molecular biomarkers of response, percentage of switched memory B cells and AID response to CpG, useful for identifying individuals at risk of poor response and also for measuring improvements in vaccines and monitoring optimal humoral responses.

Keywords: Aging, B lymphocytes, biomarkers for vaccine response, immunoglobulin class switch recombination, pH1N1

Introduction

Vaccination is the most effective method of preventing influenza, but the effects of vaccination are different in individuals of different ages (1–5). For example, in the case of seasonal influenza vaccination, there is evidence that elderly individuals who have routinely received the vaccine can still contract the infection with secondary complications leading to hospitalization, physical debilitation, exacerbation of underlying medical conditions and death (6–10).

The novel strain of pH1N1 influenza virus, which emerged in 2009 in Mexico and then spread worldwide, caused illness more among young individuals as compared with older ones (age ≥ 65 years) (11). This has been postulated to occur because a cross-reactive antibody response to pH1N1 was found in a proportion of elderly individuals, particularly those born in the second and third decade of the 20th century, that was largely absent in younger subjects (12, 13). Although pH1N1 vaccination had been recommended for older individuals, studies on the effects of age on the response to the pH1N1 vaccine are few and not focused on the B-cell response (14–16).

We have previously shown an age-related impairment in the ability of B cells to undergo Ig class switch recombination, which is due to reduced expression of both activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) and the E47 transcription factor which transcriptionally activates AID (17). More recently, results from two seasonal influenza vaccination years have shown that AID can accurately track optimal immune responses and therefore be considered a valid marker of the humoral response to the vaccine in humans (18). Here, we wanted to evaluate the effects of age on the in vivo response to the pH1N1 vaccine. The objective of this study was to establish new biomarkers which could (i) predict which individuals would respond less well and identify those for possible further vaccine enhancement and (ii) be used for future vaccine efficacy measurements.

Methods

Subjects

Experiments were conducted using blood isolated from healthy volunteers of different ages after appropriate signed consent. The study has been approved with IRB protocol #20070481. The individuals participating in the study were screened for diseases known to alter the immune response or for consumption of medications that could alter the immune response, as in our previously published work on seasonal influenza vaccination (18). All subjects were influenza-free at the time of enrollment and at the time points of blood draws and were also without symptoms associated with respiratory infections. They were all also free from influenza at 3-month follow-up.

Participants were 43 healthy subjects (age 20–75 years) and were 18 females and 25 males. Three were Black, and 40 White (of which 18 identified themselves as Hispanic Whites). For the purpose of this study, ‘elderly’ persons refer to those ≥65 years of age (n = 9; mean age 70 ± 1, age range 65–75 years). Young persons were 20–64 years of age (n = 34; mean age 42 ± 2).

Vaccination

Two pH1N1 2009 monovalent vaccines were used: Novartis NDC 66521-200-10 (subunit vaccine) and Sanofi-Pasteur NDC 49281-640-15 (split vaccine). Sixteen young and five elderly received the Novartis vaccine, whereas 18 young and 4 elderly received the Sanofi-Pasteur vaccine. The two vaccines were given in two different centers at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. Both vaccines gave similar results. Blood samples were collected immediately before vaccination (t0), 1 week (t7) and 4–6 (t28) weeks postvaccination. All elderly individuals had been vaccinated with the seasonal influenza vaccine in the previous three seasons and in the current one. Only 7/34 (20%) of the young subjects, conversely, had been vaccinated with seasonal vaccine in the previous and in the current season.

PBMC cultures

PBMC were collected by density gradient centrifugation on Ficoll–Paque premium solution (GE Healthcare). Cells were then washed three times with PBS and used either fresh or frozen. Frozen PBMC (10 × 106) were thawed in a 37°C water bath and washed twice with medium (RPMI 1640), resuspended, rested for 1 h and then counted in trypan blue to evaluate cell viability, which was usually over 80%. PBMC (1 × 106 ml−1) were cultured in complete medium (RPMI 1640, supplemented with 10% FCS, 10 μg ml−1 Pen-Strep, 1 mM Sodium Pyruvate and 2 × 10−5 M 2-ME and 2 mM l-glutamine), stimulated for 7 (fresh) or 3 (frozen) days, optimal kinetics for each, in 24-well culture plates with 5 μg ml−1 CpG (ODN 2006 InvivoGen) or with influenza vaccine (2 μl ml-1 containing 106 cells).

For each subject, the vaccine used to stimulate PBMC in vitro was the same as that given in vivo. Novartis and Sanofi-Pasteur vaccines contained 0.76 μg μl−1 and 0.74 μg μl−1 of protein, respectively. At the end of stimulation, cells were harvested, and RNA extracted for quantitative (q)PCR to evaluate AID and GAPDH mRNA expression. Although B cells in the PBMC cultures have been stimulated in the presence of other cell types, primarily T cells and monocytes–macrophages, our endpoint is to measure a B-cell response, as AID is exclusively expressed in B cells. This differs from our previous study (18) where we used magnetically separated (CD19+), purified B cells for culture. For the study here with the pH1N1 vaccine response, we found that purified B cells were unable to respond to their cognate vaccine, perhaps due to the vaccine lacking mitogenic components present previously. It is for this reason that we also compared the B-cell response in fresh and frozen PBMC (see below).

Flow cytometry

One hundred microliter of blood from each subject were stained for 20 min at 4°C with the following antibodies: APC-conjugated anti-CD19 (BD 555415), PE-conjugated anti-CD27 (BD 555441), FITC-conjugated anti-IgD (BD 555778), biotin-SP-conjugated AffiniPure F(ab′)2 fragment anti-human IgG (Jackson 109-066–098) and biotin-SP-conjugated AffiniPure F(ab′)2 fragment anti-human IgA (Jackson109-066-011). Biotin-conjugated antibodies were revealed with PerCP-conjugated streptavidin (1/40 diluted; BD 554067). Naive B cells were IgG−/IgA−CD27−, IgM memory B cells were IgG−/IgA−/CD27+/IgD+, and switched memory B cells were IgG+/IgA+, as previously shown (19–21). After staining, red blood cells were lysed using the RBC Lysing Solution BD PharmLyse (BD 555899), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Up to 105 events in the lymphocyte gate were acquired and analysed on an LSRI flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using logarithmic amplification. Single color controls were included in every experiment to determine background fluorescence and to set the gates.

As investigators have previously noted, antibody-secreting cells (ASC)/plasmablasts increase 7 days after vaccination as a marker of response (22, 23), we also investigated the level of circulating ASC/plasmablasts at t0 and t7. To detect ASC, PBMC were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD3 (BD 555339), PacBlue-conjugated anti-CD19 (Invitrogen MHCD1928), APC-H7-conjugated anti-CD20 (BD 641396), PE-conjugated anti-CD27 (BD 555441) and PerCP Cy5.5-conjugated anti-CD38 (BD 551400). ASC were CD3-/CD19+/CD20low/CD27bright/CD38bright. Samples of at least 1 × 106 events were analysed and acquired on an LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Hemagglutination inhibition assay

We evaluated the immunogenicity of the pH1N1 vaccine in young and elderly individuals before (t0) and after vaccination (t28) by hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) assay, as previously described (18, 24). The HAI test is useful for the measurement of antibody titers of sera and is the most established correlate with vaccine protectiveness (25, 26). Briefly, paired preimmunization and postimmunization serum samples from the same individual were tested simultaneously, according to Hsiung et al. (27). Serum inhibiting titers of 1/40 or greater confer protection against infection, whereas a 4-fold rise in the reciprocal of the titer from t0 to t28 indicates a positive response to the vaccine and indicates seroconversion (25).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

pH1N1-specific IgG, IgM and IgA concentrations in serum of individuals before and after vaccination were evaluated by human Ig quantitative ELISA kits (Bethyl Labs E80–104, E80–100 and E80–102, respectively), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, after coating the plates with pH1N1 vaccine at the concentration of 2 μg ml−1. Results are expressed as follows: OD values at t28-OD values at t0.

RNA extraction, reverse transcription–PCR and qPCR

mRNA was extracted from stimulated PBMC (106 ml−1) using the μMACS mRNA isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec), according to the manufacturer’s protocol, eluted into 75 μl of preheated elution buffer, stored at −80°C until use and qPCR performed as described (18). Calculations were made as follows. We determined the cycle number at which transcripts reached a significant threshold (Ct) for AID and GAPDH as control. A value for the target gene, relative to GAPDH, was calculated and expressed as ΔCt. We have chosen a 2-fold rise in AID mRNA from t0 to t28 to indicates a positive response to the vaccine (18).

Statistical analyses

Nonparametric analyses of the variables in young and elderly groups were performed by Mann–Whitney test (two-tailed), whereas correlations were performed by Spearman test, using GraphPad Prism 5 software.

Results

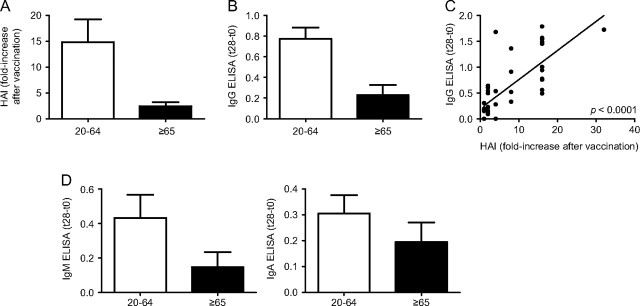

Aging decreases the pH1N1-specific serum response

We first analysed the effects of age on the in vivo response, evaluated by HAI. Sera were isolated from the blood of 34 young and 9 elderly subjects before (t0) and after (t28) pH1N1 vaccination and tested in the HAI assay. Thirty-three/34 young and 9/9 elderly subjects had a seroprotective titer (1/40) at t0. Geometric mean titers (GMT) at t0, which are the geometric mean of the reciprocal of the titers (GMT = antilog , where T is the reciprocal of the HAI titer and n is the number of samples) were comparable in young versus elderly subjects (70 versus 64, P = 0.075). Our results from previous years (2008–2009 and 2009–2010 seasonal influenza response) have shown that elderly had a significantly higher t0 titer (18). Fig. 1(A) shows that aging significantly decreases the specific HAI response to the new pH1N1 vaccine at t28. Results are expressed as fold-increase in titer after vaccination. Among the young subjects, nine did not respond to vaccination and had a fold-increase ≤4. Among the elderly subjects, seven did not respond and the response of the elderly individuals was significantly reduced as compared with that of young subjects (P = 0.0024). Although others have recently shown that the in vivo response to the pH1N1 vaccine declines from 20 to 80 years of age (15), the purpose of our study additionally was to correlate the in vivo HAI response in our subjects with the in vitro response of B cells to the vaccine.

Fig. 1.

The serum response to pH1N1 vaccination decreases with age. (A) Sera isolated from subjects of different ages, before (t0) and after vaccination (t28), were collected and analysed by HAI assay to evaluate antibody production to vaccine. Results are expressed as fold-increase in the reciprocal of the titer after vaccination, calculated as follows: reciprocal of titer values after vaccination/reciprocal of titer values before vaccination. Thirty-four young and nine elderly subjects were evaluated. The difference between young and old is significant (P = 0.0024). White column: young. Black column: elderly. (B) Sera were also evaluated in pH1N1-specific IgG ELISA. Data are expressed as OD at t28–OD at t0. The difference between young and elderly individuals is significant (P = 0.0325). White column: young. Black column: elderly. (C) Correlation between IgG ELISA and HAI. P < 0.0001 (two-tailed). Absolute OD values for IgG ranged from 0.1 to 2.3. (D) Results of pH1N1-specific IgM and IgA ELISA, respectively. Data are expressed as OD at t28–OD at t0. Absolute OD values for IgM ranged from 0.1 to 2.9 and for IgA from 0.1 to 1.4. The differences between the two age groups were not significant (P = 0.4028 and P = 0.8402 for IgM and IgA, respectively). White column: young. Black column: elderly.

The HAI assay does not distinguish the isotype of the antibodies, although it is known that IgG is the main isotype in serum, it is the major contributor to HAI and its levels are correlated with protection from influenza infection (28). Moreover, it has recently been shown that pH1N1-specific monoclonal antibodies obtained from infected, hospitalized patients were able to bind the recombinant hemagglutinin protein in an ELISA test, whereas only one-third of these antibodies displayed HAI activity (22). We also evaluated the IgG-specific response by ELISA. Results (Fig. 1B) show that aging significantly decreases the specific IgG response in serum (P = 0.0325). In our subjects, the HAI response was significantly correlated with the IgG ELISA response (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1C). Our results may differ from those above because we assayed vaccinated, not infected subjects. However, both pH1N1-specific IgM (left) and IgA (right) responses were not affected by age, although a slight decrease was observed for the IgM response (Fig. 1D). These results show for the first time that ELISA, which evaluates the binding capacity but not the function of specific antibodies, is significantly correlated with the functional measures determined by the HAI.

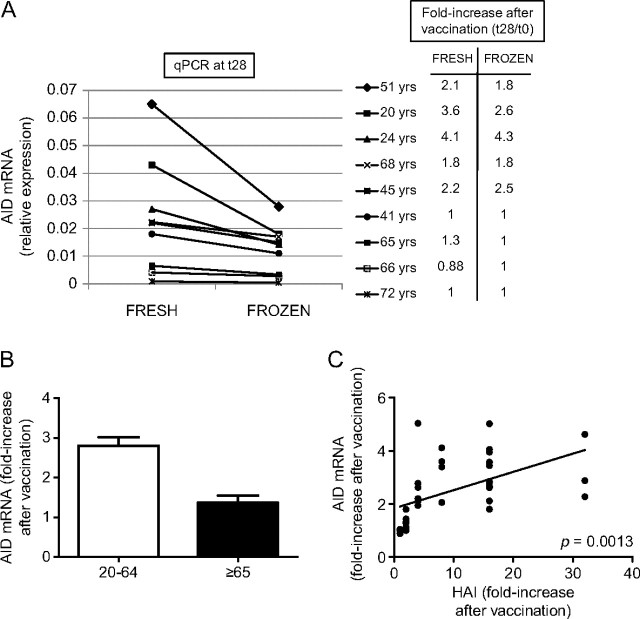

Age-related decrease in pH1N1-specific AID mRNA induction

We have used AID as a marker for optimal B-cell function in humans because it completely correlates with the ability of B cells to class switch Ig (17) and AID regulates not only class switch but also somatic hypermutation, necessary for affinity maturation of Ig V regions. We have previously shown that B cells can be stimulated in vitro by the influenza vaccine (seasonal) to induce AID and this response is up-regulated in young as compared with elderly subjects (18). We therefore started our investigation by stimulating B cells in vitro with the pH1N1 vaccine. Briefly, B cells were isolated from the PBMC of the same individuals of different ages as above, before (t0), or after (t28) pH1N1 vaccination and then stimulated in vitro for 7 days to induce optimal AID mRNA. To our surprise, we found that purified B cells did not proliferate/differentiate in response to the pH1N1 vaccine in the absence of APC and T cells (data not shown). Therefore, in order to evaluate the B-cell response to the vaccine in vitro, we stimulated frozen PBMC with the vaccine (or with CpG as control). To validate this approach, we first compared the response of fresh PBMC with that of frozen PBMC from five young and four elderly subjects. Results in Fig. 2(A) show that the qPCR values of AID in frozen PBMC cultures stimulated with the vaccine are lower than those obtained in fresh PBMC cultures from the same individuals. Nevertheless, the relative expression of AID in frozen PBMC cultures (e.g. in high versus low responder samples) is proportional to that in fresh cultures and as is the fold-increase after vaccination. We have also shown in seasonal influenza vaccinated individuals that vaccine-induced AID in purified B-cell cultures and in frozen PBMC cultures correlate (data not shown). We have thus validated that frozen PBMC in this assay give reliable results which allow their analyses not only in this report but should also be able to be used for other studies. It should also be noted that in many previous experiments with multiple stimuli (anti-CD40/IL-4, seasonal influenza vaccine, CpG), no response and very little/no cell recovery were seen with purified B cells frozen and then subsequently stimulated in vitro.

Fig. 2.

The in vitro AID response of B cells to pH1N1 vaccination decreases with age and is correlated with the serum response. (A) Fresh or frozen PBMC (106 cells ml–1), isolated from five young and four elderly individuals after vaccination (t28), were cultured with the vaccine, for 7 days. At the end of this time, cells were processed as described in Methods. Results are expressed as raw qPCR values of AID mRNA normalized to GAPDH. The right part of the figure shows the fold-increases after vaccination in AID mRNA expression in cultures of fresh and frozen PBMC. The fold-increase in AID mRNA expression after vaccination is calculated as follows: qPCR values after vaccination/qPCR values before vaccination. The difference between the two values (fresh versus frozen) is not significant in all subjects. (B) PBMC isolated from subjects of different ages, before (t0) and after vaccination (t28), were frozen. On the day of culture, PBMC were thawed and 106 cells ml–1 were cultured with the vaccine, for 3 days, optimal for frozen PBMC response (data not shown). At the end of this time, cells were processed as described in Methods. Twenty-eight young and seven elderly subjects were evaluated. Results are expressed as fold-increase in AID mRNA expression after vaccination, calculated as above. The difference between young and old is significant (P = 0.0024). White columns: young. Black columns: elderly. C. PBMC were cultured as described in B. Twenty-eight young and seven elderly subjects were evaluated. Of the seven elderly, two had a positive HAI fold-increase of 4 and 8. Results are expressed as fold-increase in HAI and AID mRNA expression after vaccination, calculated as indicated above. Spearman rho = 0.523, P = 0.0013 (two-tailed).

We then evaluated the response to the vaccine in vitro by stimulating frozen PBMC obtained at t0 and t28. Results in Fig. 2(B) show that aging significantly decreases AID mRNA expression. In more detail, 21 of the 28 young subjects showed at least a 2-fold up-regulation of AID mRNA at t28, whereas only one of seven elderly had a positive response to the vaccine. Therefore, this up-regulation was significantly higher in young than in elderly subjects (P = 0.0024).

In order to determine whether the AID response could be used as a marker to measure individuals with robust or poor serum responses, we evaluated whether the in vitro AID response of B cells to the vaccine and the in vivo HAI response were correlated. Results in Fig. 2(C) show that in vitro AID and in vivo HAI responses are significantly correlated (P = 0.0013) and suggest the possibility to use AID as a novel marker for assessing vaccine-specific and likely also other immune responses. These results are in line with our previous ones showing that a high seasonal influenza-specific in vitro AID response was significantly correlated with a high HAI response and vice versa (18).

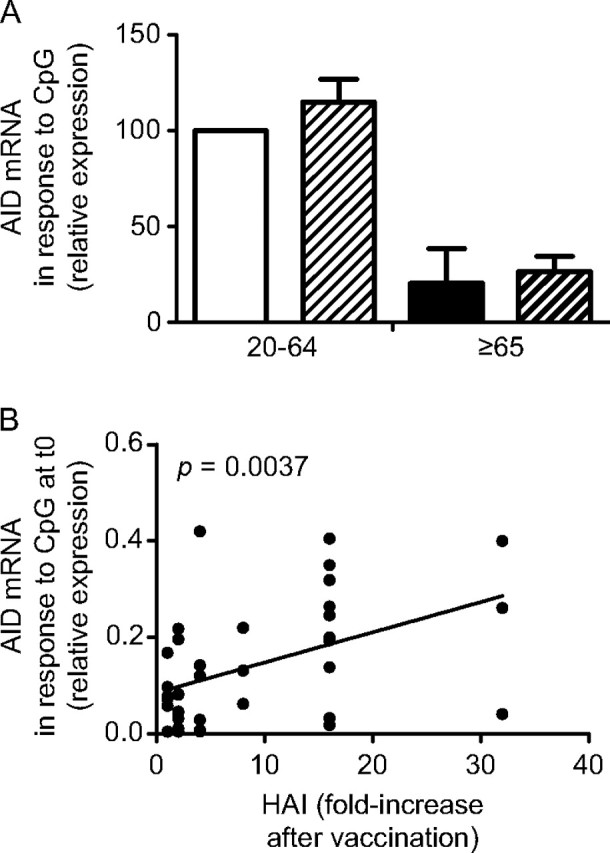

The AID response at t0 can predict the response to the pH1N1 vaccine

Our results in Fig. 2(B) show that the influenza-specific AID response is lower in aged individuals, as compared with young controls. However, as expected, the CpG response is similar before and after vaccination in both young and elderly individuals, although the elderly have significantly less CpG-induced AID response as compared with the younger adults (Fig. 3A). In order to test whether the AID at t0 could be used to predict the robustness of the influenza response, we measured AID in response to CpG at t0 and correlated this with the fold-increase in the HAI serum response. Results show that the HAI response was correlated with the CpG-induced AID at t0 (P = 0.0037) (Fig. 3B), indicating that AID in nonantigen-specific stimulated B cells can predict the ability to generate an optimal influenza vaccine response.

Fig. 3.

The AID response at t0 can predict the response to the pH1N1 vaccine. (A) Frozen PBMC were cultured with CpG, for 3 days. Twenty-eight young and seven elderly subjects were evaluated. Results are expressed as AID mRNA expression (qPCR values) at t0 and t28. The difference between young t0 versus t28 and old t0 versus t28 is not significant. The difference between young and old t0 and young and old t28 are both significant (P = 0.0335 and P = 0.0091, respectively). White column: young t0. Light diagonal column: young t28. Black column: elderly t0. Dark diagonal column: old t28. (B) Correlation between CpG-induced AID at t0 and HAI (only two elderly had a positive HAI fold-increase of 4 and 8). P = 0.0037 (two-tailed).

Switched memory B cells as markers of the response to vaccination

To identify other possible predictive markers for an optimal vaccine response, we measured the percentages of B-cell subsets at t0 and t28 in response to the pH1N1 vaccine, as evaluated by flow cytometry. Table 1 shows that the percentages of naive B cells are significantly increased by age, whereas those of IgM memory B cells did not change between young and elderly individuals, but all B subsets are decreased in number with age (20). When we evaluated switched memory B cells, we found that IgG+IgA+CD27− cells did not change between young and elderly individuals, whereas IgG+IgA+CD27+ were found decreased in elderly as compared with young at t0 (P < 0.01). For the response to the vaccine, we found that the percentages of naive, IgM memory and IgG+IgA+CD27− switched memory B cells remained the same between t0 and t28, in both young and elderly subjects. However, the percentage of IgG+IgA+CD27+ switched memory B cells increased after vaccination (t28) in young but not in elderly subjects, with a significant difference (P = 0.0012) in the fold-increase after vaccination between the two age groups, as we (18) and others (29) have already shown. Therefore, the pH1N1 vaccine, as well as other vaccines (seasonal influenza and anthrax vaccines), was able to specifically induce a subpopulation of switched memory B cells, with the IgG+IgA+CD27+ phenotype.

Table 1.

Percentages of B cell subsets from young and elderly subjects before and after H1N1 vaccination

| Naive IgG−IgA−CD27− |

IgM memory IgG−IgA−CD27+ |

Switched memory IgG+IgA+CD27− |

Switched memory IgG+IgA+CD27+ |

|||||

| Age (years) | t0 | t28 | t0 | t28 | t0 | t28 | t0 | t28 |

| 20–64 | 58 ± 2 | 57 ± 2 | 36 ± 2 | 34 ± 2 | 3 ± 0.1 | 3 ± 0.4 | 3 ± 0.2 | 6 ± 0.4a |

| ≥65 | 71 ± 3b | 70 ± 2b | 26 ± 7 | 27 ± 5 | 2 ± 0.9 | 2 ± 0.5 | 1 ± 0.2b | 1 ± 0.3b |

One hundred microliter of blood from each subject were stained as described in Methods. Results refer to CD19+ cells.

P < 0.01, indicates the difference between t0 and t28. Total numbers and percentages of B cells decrease with age by about half to 120 cells μl–1 and 6%, respectively, so although there is an increase in the % of naive cells in the elderly, the overall numbers are decreased. The t0 values here are consistent with those we have previously reported in 66 young and 46 elderly [see ref. (27)]

P < 0.01, indicates the difference between the young (20–64) and the elderly (≥65) individuals.

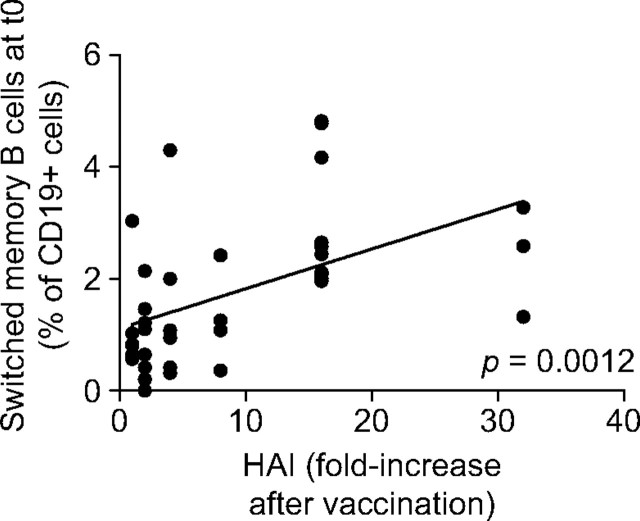

To investigate whether IgG+IgA+CD27+ switched memory B cells could be used as a predictive marker to assess the response to the pH1N1 vaccine, we correlated the percentage of this subset at t0 and the HAI response in the same individuals. Results in Fig. 4 show that the percentage of this subset of switched memory cells in the blood of prevaccinated subjects was significantly correlated with the fold-increase in the in vivo response. From these results, we propose that the subset of CD27+ switched memory B cells can be used as a predictive marker of the response to the pH1N1 vaccine here and perhaps to many if not all vaccines.

Fig. 4.

The percentage of switched memory B cells IgG+IgA+CD27+ at t0 correlates with the in vivo serum response. Correlation between switched memory B-cell percentages at t0 and HAI (only two elderly had a positive HAI fold-increase of 4 and 8). Spearman rho = 0.590, P = 0.0012 (two-tailed).

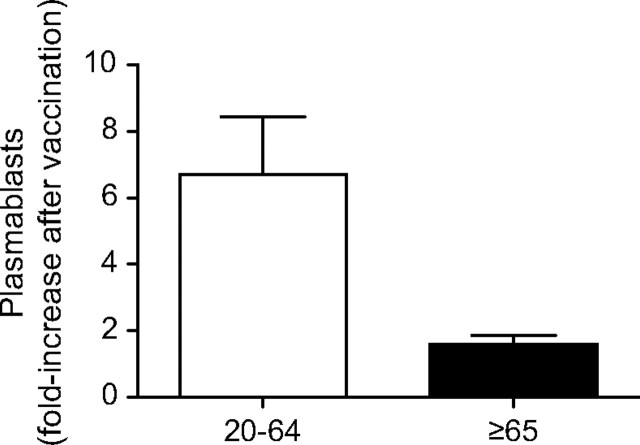

We also measured the plasmablast response at t7 after influenza vaccination in 31 subjects (24 young and 7 elderly). Others have determined that t7 is the peak for the plasmablast response, which is completely gone at t14 (22, 23, 30) and we also confirmed that. Moreover, this response at t7 is vaccine-specific, as previously shown (23, 31). Results in Fig. 5 show that although elderly subjects had a lower fold-increase in the percentages of plasmablasts as compared with younger controls, this was not significant because of the reduced numbers of subjects that came back for a blood draw at t7 (P = 0.0838). However, this trend is encouraging and we are pursuing the evaluation of plasmablasts at t7 in further B-cell vaccine response studies.

Fig. 5.

The percentage of plasmablasts increases after vaccination in young but not in elderly subjects. Two millions of PBMC from young and elderly subjects at t0 and t7 were stained as described in Methods. Twenty-four young and seven elderly subjects were evaluated. Results are expressed as fold-increase in plasmablasts percentages after vaccination, calculated as above. The difference between young and old is not significant (P = 0.0838), although a trend is observed. White columns: young. Black columns: elderly.

Discussion

The focus of the present study was to evaluate the in vivo response and the in vitro response of B cells from individuals of different ages to the pH1N1 vaccine. Our results show that aging affects both responses. Moreover, we have identified molecular biomarkers for the response to this vaccine, which we would suggest might also be effective predictors of the response to other vaccines. These biomarkers are CpG-induced AID at t0 and the percentage of switched memory B cells at t0. Other markers can also be used to evaluate a beneficial response, e.g. AID at t28, the increase in switched memory cells at t28 and the increase in plasmablasts at t7, the latter here a trend, but also present in other studies (22, 23).

Although in our study protective titers before vaccination were found in all subjects, seroconversion rates were significantly different in young and elderly subjects. Others have also shown that protective serum titers before vaccination can be observed at any age; however, in contrast with the results herein, titers to pH1N1 after vaccination were found increased more in elderly than in young individuals, due to vaccination with a cross-reactive seasonal flu vaccine during the same or previous years (14). Although others have shown increased t0 titers for elderly to the H1N1 vaccine (13) and only in those 80 or older (15), we (here) and others for 65- to 80-year-old individuals (15) have not. Surprisingly, these t0 values are lower than those we have reported in our seasonal influenza vaccine study where the elderly t0 values were higher than those of young (18). These discrepancies could be explained by differences in the history of vaccination against seasonal influenza and/or infection. Moreover, the type of vaccine received in prior years affects the serum antibody and the in vitro B-cell response to subsequent vaccination (32). Regardless, the response we are measuring, fold-increase at t28, is not a result of a difference in initial titers/activated memory cells at t0.

Here, we also show that the in vivo-specific IgG response evaluated by ELISA is significantly higher in young than in elderly individuals, whereas the specific IgM response is not. This result suggests that the pH1N1 vaccine has induced a strong T-dependent response, which is reduced with age, as opposed to the IgM response which is not significantly different between young and elderly individuals, although a trend has been observed. Moreover, the pH1N1 vaccine has induced a specific, although relatively low, IgA response, which is also present in the elderly, as others have also found (31, 33–35).

In this paper, we have also evaluated the plasmablast response at t7 after pH1N1 vaccination. Plasmablasts have been shown by us (D. Frasca, B. B. Blomberg, unpublished) and others (23, 30) to transiently appear in blood with a peak at day 7 and then disappear. This observation suggests that the fold-increase in the serum antibody response is associated with the presence of effector B cells in the blood. Therefore, the plasmablast response is another useful measure of the response to the vaccine. This has the advantage of being an early response (t7) as compared with the other biomarkers (AID and switched memory B cells), which are evaluated at t28. Moreover, in the case of seasonal influenza vaccination, it has been shown that there is a significant correlation between the concentration of specific antibodies secreted by plasmablasts at t7 and the frequency of total ASCs, as evaluated by ELISPOT (36), suggesting that the evaluation of plasmablasts can easily substitute for conventional serological assays for investigating the antibody response to the vaccine. We here show that plasmablasts are increased by vaccination in young but not in elderly individuals. Although we observed an age-related trend, the fold-increases in young and elderly subjects were not statistically different. We will evaluate plasmablasts in subsequent influenza vaccination with larger numbers of subjects.

The subset of switched memory B cells that express the memory CD27 marker is also up-regulated in young but not in elderly subjects after pH1N1 vaccination, as we have previously shown in seasonal influenza vaccinated people (18). With a different method to evaluate memory B cells, others have shown that serum antibody titers and peripheral memory B cell numbers in blood are significantly correlated in people vaccinated against Measles, Mumps, Rubella, Vaccinia and Diphtheria (37). Our results are very important because memory B cells carry the history of the individual in terms of specific immune responses and are where high-affinity antibodies reside. These cells proliferate and differentiate rapidly in recall responses generating a pool of plasma cells concomitant with an elevation in serum antibodies and plasma cells and preformed antibodies represent the first line of defense of the individual from infection (37, 38).

In conclusion, our study shows that, after pH1N1 vaccination, the serum response, the induction of AID in vaccine-stimulated cultures and the induction of switched memory B cells in vivo decrease with aging. Our results indicate that the AID response can be used as a biomarker for effective B-cell (antibody) response to the pH1N1 influenza vaccine and likely other vaccines. Other predictive biomarkers we have revealed for an optimal vaccine response are the percentage of switched memory (CD27+IgG+IgA+) B cells at t0 and the AID response to CpG at t0. These biomarkers should help to identify individuals who will have impaired responses to vaccination and therefore reduce morbidity and mortality due to infections in the elderly.

Funding

National Institutes of Heath (AG-17618 and AG-28586 to B.B.B.).

Acknowledgments

We thank people who participated in this study. We thank the personnel of the Family Medicine Department at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (in particular Dr Robert Schwartz, chairman) and Dr Sandra Chen Walta (Employee Health Manager), for help with the recruitment; Jim Phillips (Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Core Resource), for help with the Flow Cytometer and Michelle Perez, for secretarial assistance.

References

- 1.Goodwin K, Viboud C, Simonsen L. Antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly: a quantitative review. Vaccine. 2006;24:1159. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McElhaney JE. Influenza vaccine responses in older adults. Ageing Res. Rev. 2010;10:379. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McElhaney JE, Effros RB. Immunosenescence: what does it mean to health outcomes in older adults? Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2009;21:418. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simonsen L, Taylor RJ, Viboud C, Miller MA, Jackson LA. Mortality benefits of influenza vaccination in elderly people: an ongoing controversy. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2007;7:658. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70236-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Targonski PV, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Immunosenescence: role and measurement in influenza vaccine response among the elderly. Vaccine. 2007;25:3066. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Pahor M, Corti MC, Havlik RJ. Hospital diagnoses, Medicare charges, and nursing home admissions in the year when older persons become severely disabled. JAMA. 1997;277:728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross PA, Hermogenes AW, Sacks HS, Lau J, Levandowski RA. The efficacy of influenza vaccine in elderly persons. A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Ann. Intern. Med. 1995;123:518. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-7-199510010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monto AS, Ansaldi F, Aspinall R, et al. Influenza control in the 21st century: optimizing protection of older adults. Vaccine. 2009;27:5043. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simonsen L, Clarke MJ, Schonberger LB, Arden NH, Cox NJ, Fukuda K. Pandemic versus epidemic influenza mortality: a pattern of changing age distribution. J. Infect. Dis. 1998;178:53. doi: 10.1086/515616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vu T, Farish S, Jenkins M, Kelly H. A meta-analysis of effectiveness of influenza vaccine in persons aged 65 years and over living in the community. Vaccine. 2002;20:1831. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jain S, Kamimoto L, Bramley AM, et al. Hospitalized patients with 2009 H1N1 influenza in the United States. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1935. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenbaum JA, Kotturi MF, Kim Y, et al. Pre-existing immunity against swine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses in the general human population. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci USA. 2009;106:20365. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911580106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hancock K, Veguilla V, Lu X, et al. Cross-reactive antibody responses to the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1945. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcelin G, Bland HM, Negovetich NJ, et al. Inactivated seasonal influenza vaccines increase serum antibodies to the neuraminidase of pandemic influenza A(H1N1) 2009 virus in an age-dependent manner. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;202:1634. doi: 10.1086/657084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skowronski DM, Hottes TS, Janjua NZ, et al. Prevalence of seroprotection against the pandemic (H1N1) virus after the 2009 pandemic. CMAJ. 2010;182:1851. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.100910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou X, McElhaney JE. Age-related changes in memory and effector T cells responding to influenza A/H3N2 and pandemic A/H1N1 strains in humans. Vaccine. 2011;29:2169. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frasca D, Landin AM, Lechner SC, et al. Aging down-regulates the transcription factor E2A, activation-induced cytidine deaminase, and Ig class switch in human B cells. J. Immunol. 2008;180:5283. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, et al. Intrinsic defects in B cell response to seasonal influenza vaccination in elderly humans. Vaccine. 2010;28:8077. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bernasconi NL, Traggiai E, Lanzavecchia A. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science. 2002;298:2199. doi: 10.1126/science.1076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Landin AM, Blomberg BB. Age effects on B cells and humoral immunity in humans. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011;10:330. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu YC, Kipling D, Leong HS, Martin V, Ademokun AA, Dunn-Walters DK. High-throughput immunoglobulin repertoire analysis distinguishes between human IgM memory and switched memory B-cell populations. Blood. 2010;116:1070. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wrammert J, Koutsonanos D, Li GM, et al. Broadly cross-reactive antibodies dominate the human B cell response against 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus infection. J. Exp. Med. 2011;208:181. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wrammert J, Smith K, Miller J, et al. Rapid cloning of high-affinity human monoclonal antibodies against influenza virus. Nature. 2008;453:667. doi: 10.1038/nature06890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ito T, Suzuki Y, Mitnaul L, Vines A, Kida H, Kawaoka Y. Receptor specificity of influenza A viruses correlates with the agglutination of erythrocytes from different animal species. Virology. 1997;227:493. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.8323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murasko DM, Bernstein ED, Gardner EM, et al. Role of humoral and cell-mediated immunity in protection from influenza disease after immunization of healthy elderly. Exp. Gerontol. 2002;37:427. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00210-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Skowronski DM, Tweed SA, De Serres G. Rapid decline of influenza vaccine-induced antibody in the elderly: is it real, or is it relevant? J. Infect. Dis. 2008;197:490. doi: 10.1086/524146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsiung GD, Fong CKY, Landry ML. Diagnostic Virology. Yale University Press; 1994. New Haven, CT. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clements ML, Betts RF, Tierney EL, Murphy BR. Serum and nasal wash antibodies associated with resistance to experimental challenge with influenza A wild-type virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1986;24:157. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.1.157-160.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crotty S, Aubert RD, Glidewell J, Ahmed R. Tracking human antigen-specific memory B cells: a sensitive and generalized ELISPOT system. J. Immunol. Methods. 2004;286:111. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cox RJ, Brokstad KA, Zuckerman MA, Wood JM, Haaheim LR, Oxford JS. An early humoral immune response in peripheral blood following parenteral inactivated influenza vaccination. Vaccine. 1994;12:993. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sasaki S, Sullivan M, Narvaez CF, et al. Limited efficacy of inactivated influenza vaccine in elderly individuals is associated with decreased production of vaccine-specific antibodies. J. Clin. Invest. 2011;121:3109. doi: 10.1172/JCI57834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasaki S, He XS, Holmes TH, et al. Influence of prior influenza vaccination on antibody and B-cell responses. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Bruijn IA, Remarque EJ, Jol-van der Zijde CM, van Tol MJ, Westendorp RG, Knook DL. Quality and quantity of the humoral immune response in healthy elderly and young subjects after annually repeated influenza vaccination. J. Infect. Dis. 1999;179:31. doi: 10.1086/314540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Remarque EJ, de Bruijn IA, Boersma WJ, Masurel N, Ligthart GJ. Altered antibody response to influenza H1N1 vaccine in healthy elderly people as determined by HI, ELISA, and neutralization assay. J. Med. Virol. 1998;55:82. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199805)55:1<82::aid-jmv13>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Remarque EJ, de Jong JM, van der Klis RJ, Masurel N, Ligthart GJ. Dose-dependent antibody response to influenza H1N1 vaccine component in elderly nursing home patients. Exp. Gerontol. 1999;34:109. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(98)00060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He XS, Sasaki S, Narvaez CF, et al. Plasmablast-derived polyclonal antibody response after influenza vaccination. J. Immunol. Methods. 2011;365:67. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amanna IJ, Carlson NE, Slifka MK. Duration of humoral immunity to common viral and vaccine antigens. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1903. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A, Araki K, Ahmed R. From vaccines to memory and back. Immunity. 2010;33:451. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]