Abstract

Purpose: Cancer in childhood may disrupt normal developmental processes and cause psychosocial problems in adolescent survivors of childhood cancers (ACCSs). Previous studies report inconsistent findings. Study aims were to assess subjective well-being (SWB), psychological distress, and school contentment in survivors of three dissimilar childhood cancers. Patients and methods: Nordic patients treated for acute myeloid leukemia (AML), infratentorial astrocytoma (IA), and Wilms tumor (WT) in childhood from 1985 to 2001, aged ≥1 year at diagnosis, and aged 13–18 years at the time of study were eligible for this questionnaire-based survey that included items on SWB, psychological distress, school contentment, self-esteem, and personality traits; 65% (151/231) responded. An age-equivalent group from a Norwegian health survey (n=7910) served as controls. Results: The median age of ACCSs was 16 years; 52% were males. ACCSs reported better SWB (p=0.004) and self-esteem (p<0.001). They had fewer social problems in school (p=0.004) and their school contentment tended to be higher than controls. SWB and school contentment were positively influenced by self-esteem. However, ACCSs reported higher levels of psychological distress (p=0.002), mostly attributable to general worrying. No significant differences in outcomes were found across diagnoses, and time since diagnosis did not significantly affect the results. Conclusion: The overall emotional functioning of ACCSs was good, possibly due to changes in their perception of well-being after having survived a life-threatening disease. However, they seemed more worried than their peers. This may cause an additional strain at a vulnerable period in life.

The improved prognosis for childhood cancers has led to increased focus on the survivors' mental and social health.1–4 Studies on emotional and socio-behavioral functioning in adolescent survivors have yielded inconsistent findings that may be attributed to mixed and small-sized samples. Many studies have used selected control groups or no comparisons. Also, some studies have used instruments lacking adequate psychometric properties.4,5 Some reports have demonstrated increased levels of anxiety and depression among survivors compared to population norms or matched controls,6–9 while others have found no differences.10–13 Findings on self-esteem have been conflicting, with some studies reporting lower levels in survivors6,8 but others finding levels comparable to controls.14,15 Well-being has mostly been assessed as part of quality of life (QOL) assessments, demonstrating similar results between survivors and comparison groups.1,2,4 Results on school performance have also been reported, mostly focusing on educational achievement, and showing learning difficulties in some studies16,17 but not in others.18,19 Inconclusive results in previous reports call for further systematic studies of psychological well-being and school contentment in adolescent survivors of childhood cancer (ACCSs).

Childhood cancer may cause disruption to normal developmental processes.20 Frequent hospitalizations, separation from family and friends, absence from school, fear of the unknown, and unpleasant side effects are all potential stressors that might increase the risk for later psychological problems. Adolescence is a critical period in the psychological and social development toward adulthood, and is associated with a significant increase in psychological problems such as depression in the general population, particularly among girls.21–23 Vulnerabilities might increase the risk of developing psychosocial problems in this period, and the cancer experience might represent such a vulnerability.24

Contentment in school is an important factor in adolescence, when social integration and good relations with peers are significant predictors for well-being. School-related stress includes conflicts with friends, pupils, or teachers, or a perception of schoolwork pressure, and may result in withdrawal and loneliness.25 Adolescents with high school contentment are less likely to suffer from emotional problems and are more likely to take part in social and school-related activities.26 Neuropsychological sequelae after cancer can impede school performance and negatively affect the school contentment of survivors.1,2

Studies on the emotional functioning of ACCSs have largely been conducted in samples of mixed diagnoses or high incidence cancers, such as acute lymphatic leukemia and brain tumors.5,10,12,14 Due to the heterogeneity of the disease course and treatment, emotional functioning after different cancer diagnoses may vary. Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), infratentorial astrocytoma (IA), and Wilms tumor (WT) are different low incidence cancers. AML treatment consists of intensive chemotherapy, sometimes supplemented with stem cell transplantation (SCT), while most IAs need only surgical treatment.27,28 Treatment for WT usually consists of chemotherapy, surgery, and sometimes radiotherapy.29

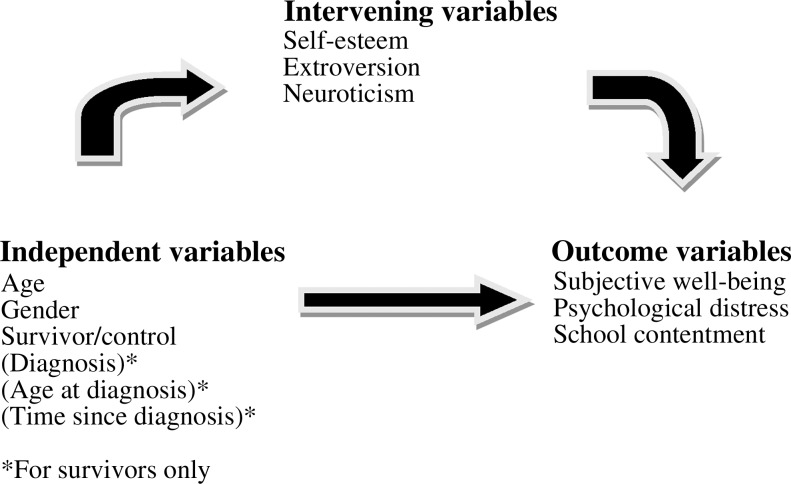

This paper is a part of a larger study on psychosocial late effects after childhood AML, IA, and WT. We have found that a significant number of young adult survivors report problems with social functioning, but our hypothesis about a relationship between intensive treatment and more psychosocial problems has not been confirmed.19,30 According to a literature review, associations between school contentment and emotional functioning have not previously been assessed in ACCSs. Therefore, study aims were to assess if ACCSs differed from controls in overall subjective well-being (SWB), psychological distress, and school contentment, and to what extent these differences were mediated by variations in self-esteem and personality traits (extroversion and neuroticism; Fig. 1). Our hypothesis was that ACCSs would have more problems with emotional functioning and be less content in school than age-matched peers.

FIG. 1.

The analytic model—the effect of independent and intervening variables on emotional functioning.

Methods

Participants

ACCSs

The five Nordic countries (Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland) collaborate closely through the Nordic Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology (NOPHO). All Nordic pediatric cancer patients are registered in the same registry and receive similar diagnosis-specific treatment according to standardized protocols.

Patients treated for childhood AML, IA, or WT in the Nordic countries from 1985 through 2001 were identified from the NOPHO registry. Inclusion criteria were: (1) histologically verified diagnosis; (2) treatment according to established protocols, though some local variations may have occurred; (3) age ≥1 year at diagnosis; (4) age ≥13 years and ≤18 years at time of assessment; (5) complete remission at time of assessment; and (6) no cancer treatment during the last three years. Survivors with mental retardation or Down's syndrome were not included. A specially designed questionnaire package was sent to eligible survivors with one written reminder after three weeks.

Controls

Between 1995 and 1997, the Nord-Trøndelag health study (HUNT), a population-based health survey, was conducted in central Norway.31 This county is considered representative of Norway in most respects.32 All students in junior and senior high school (ages 13–19) were among the invited participants and included in a sub-study (“Young-HUNT”).31 A total of 8984 (88.1%) participants completed a questionnaire during one school hour. They responded to the same items on mental health and school contentment as in the present study.22,33 All participants aged 13–18 years (n=7910) served as a comparison group in the present study.

Measures

The questionnaire package included age-appropriate items that focused on subjective well-being, psychological distress, school contentment, self-esteem, and personality traits. Translations into the different Nordic languages were done using the standard International Quality of Life Assessment (IQOLA) guidelines for translation, with two forward and two backward translations.34 A national coordinator was responsible for the data collection and management in each country.

Subjective well-being was measured by a short version of the SWB scale developed by Moum et al.35 The scale comprises three items covering components related to cognition (life satisfaction), and positive (happy/strong) and negative affect (worn out/sad). Responses on the 7-point scale ranging from “most negative” (1) to “most positive” (7) were summarized as a SWB index ranging from 3 to 21. The scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity in a number of studies.22,36,37 The internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the scale was 0.75 in this study.

Psychological distress symptoms were measured by five items from the Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (SCL-25).22,33 The items were scored on a 4-point scale ranging from “not at all” (1) to “extremely” (4), with high scores indicating the most distress. Previous publications have shown that this short version, the SCL-5 scale, correlates highly (r>0.90) with the full-length scale and is a reliable and valid measure of psychological distress.38,39 The SCL-5 reached a Cronbach's α of 0.79 in the present study.

School contentment was assessed by asking participants to respond to 14 statements regarding perceived school functioning and contentment. Items were formulated by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health for the Young-HUNT survey31 and had been used in a study of adolescents' mental health.22 Exploratory factor analyses revealed two highly meaningful dimensions, including 11 of the statements. One factor named school problems included items such as “problems with concentration in class” and “communication with the teacher and students.” Another factor named school contentment included items such as “contentment in class” and “contentment with test results.” Additive weighted indexes representing these subdimensions were retained and used as dependent variables. Items were scored on a 4-point scale ranging from “never” (1) to “very often” (4). Cronbach's α was 0.66 for both indexes.

Self-esteem was measured by the Rosenberg self-esteem scale.40 A shortened Norwegian version was validated in a study using data from the Young-HUNT survey.41 The study measured the self-acceptance aspect of self-esteem with four items scored on a 4-point scale, with a higher score indicating better self-esteem. Four questions, correlating 0.80–0.95 with the total score in the 10-item version, were selected as the subset best predicting scores on the full self-esteem scale41 with a Cronbach's α of 0.73.

Personality traits (extroversion/neuroticism) were assessed by the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ).42 A short version previously developed by multivariate analyses of data from the original Norwegian translation of EPQ41 showed a highly satisfactory correlation with the full scale.43 The two subscales of extroversion and neuroticism (each including six items) showed acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach's α was 0.60 and 0.65 respectively). The answers were “no” (1) and “yes” (2), yielding scores of 6–12, with higher scores indicating more extroversion/neuroticism.

Personality and self-esteem may be regarded as traits and thus should be more stable than the other outcome variables.44 Nevertheless, they may be permanently affected by major life events such as surviving cancer. These traits were used as intervening variables between survivorship and the other outcome variables (Fig. 1).

Ethical considerations

Approval was obtained from the NOPHO Scientific Committee, the Norwegian Social Science Data Services, the National Committees for Medical Research Ethics, and the Finnish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. All participants signed an informed consent and files were encrypted before data management.

Statistics

Differences in characteristics across groups were analyzed with t-tests, chi-square tests, and one-way ANOVAs with post hoc tests. Correlations and linear multiple hierarchical regression analyses were performed to identify associations between independent, intervening, and outcome variables. Multicollinearity was tested for, and the Pearson correlation coefficient was <0.60 for all variables. Due to the observational design and the multiplicity of tests, the significance level was set at <0.01. By comparing the survivors to a relatively large group of normal controls, the power is increased, and thus the risk of type II errors is reduced. This might infer that clinically insignificant differences become statistically significant. Effect size, assessed by Cohen's d, was calculated in order to evaluate the clinical meaningfulness of differences. Differences in gender and age at diagnosis and assessment were controlled for in the regression analyses. Analyses were performed by the SPSS statistical software version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

There were 233 ACCSs eligible for this study, but two questionnaires were returned unanswered due to unknown address. Of the remaining 231, 151 returned completed questionnaires (65%). The response rate was highest in Denmark (76%) compared to 58% in Finland and about 65% for the other countries. Among the WT survivors, the response rate was 70% (80/114) compared to 67% among AML (34/51) and 56% among IA survivors (37/66). Responders tended to be younger than non-responders (although not significantly), but the groups were otherwise similar.

Demographic and medical characteristics

The gender distribution was similar in ACCSs and controls; median age at assessment was 16 years in both groups. Age at diagnosis ranged from 1 to 13 years (mean 5.5 years) among the ACCSs, and time from diagnosis to assessment ranged from 4 to 16 years (Mean [M]=11 years; Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Medical Characteristics of Study Participants

| Variables | Survivors n=151 | Comparison group n=7910 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | n | % | n | % | |

| Male | 78 | 51.7 | 3982 | 50.3 | NS |

| Female | 73 | 48.3 | 3928 | 49.7 | |

| Age at assessment (years) | NS | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 16 | (1.7) | 16 | (1.5) | |

| Diagnosis | n | % | |||

| AML | 34 | 22.5 | |||

| IA | 37 | 24.5 | |||

| WT | 80 | 53.0 | |||

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.5 | (2.9) | |||

| AML | 6.5 | (3.4) | |||

| IA | 6.2 | (2.9) | 0.003 | ||

| WT | 4.8 | (2.4) | |||

| Time since diagnosis (years) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 10 | (3.2) | |||

| AML | 9.12 | (3.7) | |||

| IA | 10.0 | (3.4) | NS | ||

| WT | 10.9 | (2.8) | |||

| Treatment | n | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 13 | ||||

| Chemotherapy, surgery | 55 | ||||

| Chemotherapy, radiation, surgery | 22 | ||||

| Radiation, surgery | 4 | ||||

| Surgery | 31 | ||||

| Stem cell transplantation | 22 | ||||

| Unknown | 4 | ||||

AML, acute myeloid leukemia; IA, infratentorial astrocytoma; NS, not significant; SD, standard deviation; WT, Wilms tumor.

More than two-thirds of ACCSs had surgery as part of their treatment; 90 (60%) received chemotherapy, and 26 received radiotherapy. Twenty-two had undergone SCT, of which 21 were AML patients.

Differences in outcome variables between groups

ACCSs reported significantly better SWB (p=0.004) and self-esteem (p<0.001) than controls (Table 2). Differences in self-esteem were greater among females (M=12.8 vs. 11.5, p<0.001) than males (M=13.2 vs. 12.7, p<0.05). However, more psychological distress was found among the ACCSs relative to controls (p=0.002). ACCSs reported fewer problems in school (p=0.004) and tended to be more content in school, although not significantly. Controls showed higher scores on neuroticism (p=0.007). No difference was found for extroversion. No significant difference was found across diagnoses for any of the outcome variables, although AML survivors tended to report the highest levels of SWB and self-esteem and the lowest level of distress (data not shown). Time since diagnosis did not significantly affect the results (data not shown).

Table 2.

Differences in Mean Values of Emotional Functioning and School Contentment Between Survivors and the General Population

| |

Survivors n=151 |

Comparison group n=7910 |

|

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome variables | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | p-value | Cohen's d* |

| Subjective well-being (range 3–21) | 16.6 | 2.7 | 15.9 | 2.7 | 0.004 | 0.26 |

| Symptom checklist (SCL-5) (range 5–20) | 7.8 | 3.1 | 7.2 | 2.4 | 0.002 | 0.22 |

| School problems (range 5–20) | 7.6 | 2.1 | 8.1 | 2.0 | 0.004 | −0.24 |

| School contentment (range 6–24) | 17.1 | 3.1 | 16.7 | 2.8 | NS | 0.14 |

| Rosenberg self-esteem (range 4–16) | 13.0 | 2.1 | 12.1 | 2.1 | <0.001 | 0.43 |

| Neuroticism (range 6–12) | 8.3 | 1.9 | 8.7 | 1.8 | 0.007 | −0.22 |

| Extroversion (range 6–12) | 10.5 | 1.4 | 10.7 | 1.4 | NS | −0.09 |

An effect is small when d is ∼0.20, an effect is medium-sized when d is ∼0.50, and an effect is large when d is ∼0.80.

Regression analyses

The multivariate analyses showed that self-esteem strongly influenced the other outcome variables, especially SWB and school contentment, in which more than 80% of the group differences appeared to be mediated by differences in self-esteem (Table 3). Neuroticism and extroversion did not significantly influence the difference between ACCSs and controls for any of the variables, except for psychological distress. Here the relatively low levels of neuroticism among ACCSs, combined with a very strong association between neuroticism and distress, created a situation of statistical suppression, that is, the difference between comparison groups in psychological distress actually increased when neuroticism was controlled for. An item-by-item analysis of the distress scale revealed that the difference between ACCSs and controls was primarily due to higher mean scores among survivors on one item: “more worries about different things.” School contentment was positively associated with subjective well-being, but not significantly so (results not shown).

Table 3.

Effects of Intervening Variables on Outcome Variables for the Entire Sample and Differences for Outcome Variables Between Survivors and Controls

| |

Effect of intervening variables on outcome variables |

Difference between survivors and controls (ref. group) controlling in three blocks for various intervening variables |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

Self-esteem (range 4–16) |

Extroversion (range 6–12) |

Neuroticism (range 6–12) |

I Age/gender |

II+Self-esteem |

III+Personality traits |

|

||||||

| Outcome variables | Ba | p | B | p | B | p | B | p | B | p | B | p | Adjusted R2(for blocks I, II, and III)b |

| Subjective well-being (high=positive well-being) | 0.663 | <0.001 | 0.258 | <0.001 | −0.444 | <0.001 | 0.712 | 0.002 | 0.120 | 0.541 | 0.126 | 0.497 | 0.046/0.288/0.374 |

| Psychological distress (high=much distress) | −0.474 | <0.001 | −0.068 | <0.001 | 0.634 | <0.001 | 0.655 | 0.001 | 1.054 | <0.001 | 1.109 | <0.001 | 0.077/0.230/0.402 |

| School problems (high=many problems) | −0.197 | <0.001 | 0.328 | <0.001 | 0.214 | <0.001 | −0.558 | 0.001 | −0.392 | 0.020 | −0.279 | 0.084 | 0.010/0.050/0.119 |

| School contentment (high=contented) | 0.553 | <0.001 | 0.204 | <0.001 | −0.165 | <0.001 | 0.492 | 0.036 | 0.042 | 0.845 | 0.068 | 0.751 | 0.003/0.159/0.179 |

| Self-esteem (high=good) | 0.231 | <0.001 | −0.435 | <0.001 | 0.850 | <0.001 | 0.706 | <0.001 | 0.085/0.248 | ||||

| Extroversion (high=extroverted) | 0.120 | <0.001 | −0.063 | <0.001 | −0.147 | 0.202 | −0.268 | 0.018 | −0.275 | 0.015* | 0.010/0.053/0.059 | ||

| Neuroticism (high=neurotic) | −0.324 | <0.001 | −0.091 | <0.001 | −0.409 | 0.005 | −0.123 | 0.363 | −0.147 | 0.275** | 0.061/0.207/0.211 | ||

Unadjusted coefficient; bHow much of the variability in each outcome variable is accounted for by adding the intervening variables. *Only neuroticism; **only extroversion.

Discussion

The overall emotional functioning of Nordic adolescent survivors of AML, IA, and WT is satisfactory based on self-reported scores, and is comparable to an age-adjusted control sample assumed to be representative for the general population.

ACCSs reported better subjective well-being than the controls. The SWB instrument used refers to a multidimensional evaluation of life, and is considered moderately consistent across situations and the lifespan.36,37 Previous studies have measured QOL after childhood cancer using different instruments, and many confirm generally positive results in the majority of survivors.1,2,4,45 This may result from changes in perspectives of life satisfaction and well-being after having survived a life-threatening disease (a response shift).5,46,47 The ACCSs also reported significantly better self-esteem than controls. The literature shows conflicting results.4,6,8,15 Langeveld et al., who used the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in 400 survivors of childhood cancers, found they had a level of self-esteem comparable to their peers.14 The reasons for the positive results in the present study are not fully explained by the data, but it is possible that ACCSs may have been subject to increased attention because of their illness. Others have reported increased confidence and strengthened relationships with family and friends as positive outcomes of cancer, supporting this interpretation.48

ACCSs were more troubled with psychological distress than controls. The literature shows conflicting findings on this aspect,6,8,12,13,49,50 which may be attributed to the use of different instruments and heterogeneous study samples. In the present study, the level of distress seemed to increase with age, independent of time since diagnosis. As the non-responders were somewhat older than the participating ACCSs, the psychological distress may be slightly underestimated. The distress was more pronounced among females, in line with other studies.6,49 It is reasonable to assume that the cancer experience changes its psychological meaning from childhood into adulthood. Similarly, increased worrying such as more concern about future health might be more pronounced as adulthood comes closer.

ACCSs experienced fewer problems in school compared to controls. This may reflect the personal growth and maturity that many survivors experience.48 Previous studies in childhood cancer survivors have mainly focused on learning difficulties.16,17,19 This study focuses on school contentment, which is an important indicator of social functioning. ACCSs also reported higher contentment in school, an effect greatly mediated by higher levels of self-esteem among the survivors. The fact that survivors of AML, IA, and WT are generally at low risk for neuropsychological sequelae such as learning difficulties may also have led to higher school contentment and fewer school problems.

Self-esteem was the intervening variable with the most pronounced effect. It was strongly correlated to SWB. Differences in SWB between ACCSs and controls could for the most part be explained by the influence of self-esteem. SCL-5 may measure distress as a consequence of life events, including morbidity, while neuroticism is a personality trait.39,51 ACCSs scored higher on questions regarding worries than on questions regarding emotional instability. They also had lower scores on neuroticism than the controls. The reason for lower neuroticism among the ACCSs is unclear. De Clercq et al. found higher QOL but no difference for personality traits in survivors aged 8–14 years compared to healthy schoolchildren.47

There were surprisingly small differences across diagnoses, time since diagnosis, and treatment modalities. A recent study showed more anxiety and fewer positive health beliefs in survivors with the highest level of treatment intensity;20 this was not confirmed here. On the contrary, AML patients reported the highest levels of SWB and self-esteem and the lowest level of distress, although this was not significant. This may reflect the aforementioned response shift or change in the outlook on life that may be more pronounced in the most life-threatening diagnoses.

Several factors that strengthen this study are worth pointing out. This study measures self-reported SWB directly through three components and not as part of a multidimensional QOL instrument. It focuses on school contentment while previous studies have mainly focused on learning difficulties and academic achievement among survivors. The instruments used have demonstrated acceptable validity and reliability and have been used in several studies in adolescents.22,33,52 The outcome variables and model for analyses give an insight into the assumed causal relationships between important outcomes for ACCSs. The study is population-based with a representative comparison group. Studies specifically focusing on ACCSs are relatively scarce and comparison with healthy peers is necessary for a valid interpretation of results in this transitional period in life.

Among the possible limiting factors for the study may be the selection of a national control sample. However, the homogeneity across the Scandinavian countries supports the argument that this sample is fairly representative of Nordic adolescents. The fact that few studies in this age group present comparisons with population reference data should outweigh possible disadvantages. The mode of administration may have caused some bias, as the controls completed the questionnaire at school while the ACCSs received their questionnaire by mail. Table 2 shows that despite statistically significant differences, the clinical difference may not be as large. There may also be smaller differences across the groups that are not discovered by the variables or methods used. The survivors of IA had the lowest response rate—only 58%. One possible explanation is that some of these survivors did not identify themselves as cancer survivors, as they were treated with surgery only and had few follow-up visits. This assumption is supported by the fact that some IA respondents answered that they had never had a malignant disease.

The conclusion is that the great majority of adolescent survivors of AML, IA, and WT in childhood have adjusted well emotionally. However, they are more worried than adolescents from the general population. That may result in additional strain on their resources in a vulnerable period of their lives. This study cannot point to survivors at particular risk of psychosocial problems during adolescence. To examine this, longitudinal studies are necessary. However, we strongly believe that medical follow-up during this period should include screening for psychosocial difficulties in well-being, school performance, and emotional distress to provide support as necessary.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the respondents who participated in the study. We also thank Kirsten Marie Skandsen, Kristine Finset, and Ann-Marie Jacobsson for participating in data collection and management. The study was supported by a grant from the Norwegian Cancer Society (Grant no. 05075/001) and the Nordic Cancer Union (Grant no. NF-55014/001).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Langeveld NE. Stam H. Grootenhuis MA. Last BF. Quality of life in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2002;10:579–600. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeltzer LK. Recklitis C. Buchbinder D, et al. Psychological status in childhood cancer survivors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2396–2404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oeffinger KC. Nathan PC. Kremer LC. Challenges after curative treatment for childhood cancer and long-term follow up of survivors. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:251–273. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.10.009. xiii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDougall J. Tsonis M. Quality of life in survivors of childhood cancer: a systematic review of the literature (2001–2008) Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1231–1246. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0660-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stam H. Grootenhuis MA. Last BF. Social and emotional adjustment in young survivors of childhood cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2001;9:489–513. doi: 10.1007/s005200100271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Servitzoglou M. Papadatou D. Tsiantis I. Vasilatou-Kosmidis H. Psychosocial functioning of young adolescent and adult survivors of childhood cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:29–36. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0278-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shemesh E. Annunziato RA. Shneider BL, et al. Parents and clinicians underestimate distress and depression in children who had a transplant. Pediatr Transplant. 2005;9:673–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2005.00382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Essen L. Enskar K. Kreuger A, et al. Self-esteem, depression and anxiety among Swedish children and adolescents on and off cancer treatment. Acta Paediatr. 2000;89:229–236. doi: 10.1080/080352500750028889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zebrack BJ. Zeltzer LK. Whitton J, et al. Psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of childhood leukemia, Hodgkin's disease, and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatrics. 2002;110:42–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elkin TD. Phipps S. Mulhern RK. Fairclough D. Psychological functioning of adolescent and young adult survivors of pediatric malignancy. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1997;29:582–588. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-911x(199712)29:6<582::aid-mpo13>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross L. Johansen C. Dalton SO, et al. Psychiatric hospitalizations among survivors of cancer in childhood or adolescence. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:650–657. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsson G. Mattsson E. von Essen L. Aspects of quality of life, anxiety, and depression among persons diagnosed with cancer during adolescence: a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1062–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zebrack BJ. Zevon MA. Turk N, et al. Psychological distress in long-term survivors of solid tumors diagnosed in childhood: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:47–51. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langeveld NE. Grootenhuis MA. Voute PA, et al. Quality of life, self-esteem and worries in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13:867–881. doi: 10.1002/pon.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauld C. Anderson V. Arnold J. Psychosocial aspects of adolescent cancer survival. J Paediatr Child Health. 1998;34:120–126. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1998.00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langeveld NE. Ubbink MC. Last BF, et al. Educational achievement, employment and living situation in long-term young adult survivors of childhood cancer in the Netherlands. Psychooncology. 2003;12:213–225. doi: 10.1002/pon.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrera M. Shaw AK. Speechley KN, et al. Educational and social late effects of childhood cancer and related clinical, personal, and familial characteristics. Cancer. 2005;104:1751–1760. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boman KK. Lindblad F. Hjern A. Long-term outcomes of childhood cancer survivors in Sweden: a population-based study of education, employment, and income. Cancer. 2010;116:1385–1391. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johannsdottir IM. Loge JH. Hjermstad MJ, et al. Social outcomes in young adult survivors of low incidence childhood cancers. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:110–118. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kazak AE. Derosa BW. Schwartz LA, et al. Psychological outcomes and health beliefs in adolescent and young adult survivors of childhood cancer and controls. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2002–2007. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin HC. Tang TC. Yen JY, et al. Depression and its association with self-esteem, family, peer and school factors in a population of 9586 adolescents in southern Taiwan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:412–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Storksen I. Roysamb E. Moum T. Tambs K. Adolescents with a childhood experience of parental divorce: a longitudinal study of mental health and adjustment. J Adolesc. 2005;28:725–739. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avenevoli S. Knight E. Kessler R. Merikangas K. Epidemiology of Depression in Children and Adolescents. In: Abela J, editor; Hankin B, editor. Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 6–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nes RB. Roysamb E. Reichborn-Kjennerud T, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in young adults: genetic and environmental influences on stability and change. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10:450–461. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.3.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murberg TA. Bru E. The role of neuroticism and perceived school-related stress in somatic symptoms among students in Norwegian junior high schools. J Adolesc. 2007;30:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kristjansson AL. Sigfusdottir ID. Allegrante JP. Helgason AR. Adolescent health behavior, contentment in school, and academic achievement. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33:69–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gustafsson G. Lie S. Acute Leukemias. In: Voute PA, editor; Kalifa C, editor; Barrett A, editor. Cancer in Children—Clinical Management. 4th. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Camargo B. Weitzman S. Nephroblastoma. In: Voute PA, editor; Kalifa C, editor; Barrett A, editor. Cancer in Children—Clinical Management. 4th. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 259–273. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medlock M. Infratentorial Astrocytoma. In: Keating R, editor; Goodrich J, editor; Packer R, editor. Tumors of the Pediatric Central Nervous System. New York: Thieme; 2001. pp. 199–205. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johannsdottir IM. Hjermstad MJ. Moum T, et al. Increased prevalence of chronic fatigue among survivors of childhood cancers: a population-based study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:415–420. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.HUNT. [Aug 16;2006 ]. www.ntnu.no/hunt www.ntnu.no/hunt

- 32.Holmen J. Midthjell K. Krüger O, et al. The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study 1995-97 (HUNT 2): objectives, contents, methods and participation. Norsk Epidemiologi. 2003;13:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Storksen I. Roysamb E. Holmen TL. Tambs K. Adolescent adjustment and well-being: effects of parental divorce and distress. Scand J Psychol. 2006;47:75–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ware J. Gandek B. Keller S. IQOLA Group. Evaluating Instruments Used Cross-Nationally: Methods from the IQOLA Project. In: Spilker B, editor. Quality of Life and Pharmaeconomics in Clinical Trials. 2nd. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Press; 1996. pp. 681–692. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moum T. Naess S. Sorensen T, et al. Hypertension labelling, life events and psychological well-being. Psychol Med. 1990;20:635–646. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700017153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Røysamb E. Harris JR. Magnus P, et al. Subjective well-being. Sex-specific effects of genetic and environmental factors. Pers Individ Differ. 2002;32:211–223. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nes RB. Roysamb E. Tambs K, et al. Subjective well-being: genetic and environmental contributions to stability and change. Psychol Med. 2006;36:1033–1042. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strand BH. Dalgard OS. Tambs K. Rognerud M. Measuring the mental health status of the Norwegian population: a comparison of the instruments SCL-25, SCL-10, SCL-5 and MHI-5 (SF-36) Nord J Psychiatry. 2003;57:113–118. doi: 10.1080/08039480310000932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tambs K. Moum T. How well can a few questionnaire items indicate anxiety and depression? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87:364–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberg M. Society and Adolescent Self-Image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bjornelv S. Nordahl HM. Holmen TL. Psychological factors and weight problems in adolescents. The role of eating problems, emotional problems, and personality traits: the Young-HUNT study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;46:353–362. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0197-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eysenck H. Eysenck S. Manual of the EPQ. London: Hodder & Stoughton; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tambs K. (In Norwegian) Valg av Spørsmål til Kortversjoner av Etablerte Psykometriske Instrumenter. Forslag til Framgangsmåte og Noen Eksempler. In: Sandanger I, editor; Sørgaard K, editor; Ingebrigtsen G, editor; Nygaard J, editor. Ubevisst Sjeleliv og Bevisst Samfunnsliv. Psykisk Helse i en Sammenheng. Festskrift til Tom Sørensens 60 års Jubileum. Oslo: University of Oslo; 2004. pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Canals J. Vigil-Colet A. Chico E. Marti-Henneberg C. Personality changes during adolescence: the role of gender and pubertal development. Pers Individ Differ. 2005;39:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zebrack BJ. Chesler MA. Quality of life in childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2002;11:132–141. doi: 10.1002/pon.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Apajasalo M. Sintonen H. Siimes MA, et al. Health-related quality of life of adults surviving malignancies in childhood. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:1354–1358. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(96)00024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.de Clercq B. de Fruyt F. Koot HM. Benoit Y. Quality of life in children surviving cancer: a personality and multi-informant perspective. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29:579–590. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wicks L. Mitchell A. The adolescent cancer experience: loss of control and benefit finding. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2010;19:778–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michel G. Rebholz CE. von der Weid NX, et al. Psychological distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer: the Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1740–1748. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mackie E. Hill J. Kondryn H. McNally R. Adult psychosocial outcomes in long-term survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and Wilms' tumour: a controlled study. Lancet. 2000;355:1310–1314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eysenck H. Genetic and environmental contributions to individual differences: the three major dimensions of personality. J Pers. 1990;58:245–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Breidablik HJ. Meland E. Lydersen S. Self-rated health in adolescence: a multifactorial composite. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36:12–20. doi: 10.1177/1403494807085306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]