Abstract

Background

Surgeons may be reluctant to withdraw postoperative life support after a poor outcome.

Methods

A cross-sectional random sample U.S. mail survey of 2100 surgeons who routinely perform high-risk operations. We used a hypothetical vignette of a specialty-specific operation complicated by a hemiplegic stroke and respiratory failure. On postoperative day 7 the patient and family request withdrawal of life-supporting therapy. We experimentally modified the timing and role of surgeon error to assess their influence on surgeons’ willingness to withdraw life-supporting care.

Results

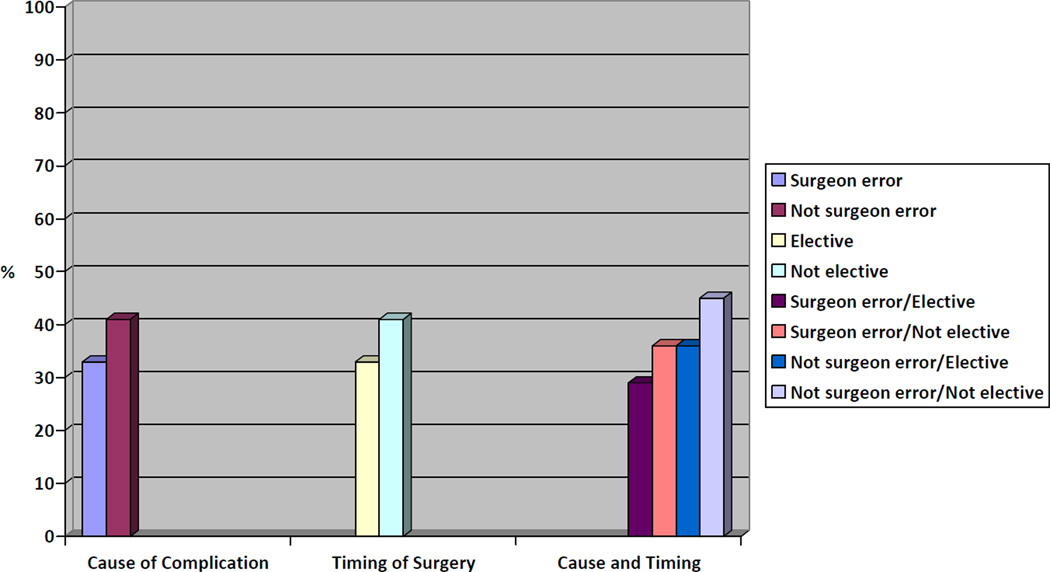

The adjusted response rate was 56%. Sixty-three percent of respondents would not honor the request to withdraw life-supporting treatment. Willingness to withdraw life-support was significantly lower in the setting of surgeon error (33% vs. 41%, p<0.008) and elective operations rather than emergency cases (33% vs. 41%, P=0.01). After adjustment for specialty, years of experience, geographic region, and gender, odds of withdrawing life-supporting therapy were significantly greater in cases where the outcome was not explicitly from error during an emergency operation as compared to iatrogenic injury in elective cases (odds ratio 1.95, 95% confidence intervals 1.26–3.01). Surgeons who did not withdraw life-support were significantly more likely to report the importance of optimism regarding prognosis (79 vs. 62%, p<0.0001) and concern the patient could not accurately predict future quality of life (80 vs. 68%, p<0.0001).

Conclusions

Surgeons are more reluctant to withdraw postoperative life-supporting therapy for patients with complications from surgeon error in the elective setting. This may also be influenced by personal optimism and a belief that patients are unable to predict the value of future health states.

BACKGROUND

“When the patient of an internist dies, his colleagues ask"What happened?”, when the patient of a surgeon dies, his colleagues ask"What did you do?’”

- Charles Bosk, To Forgive and Remember(1)

Surgeons embrace an ethos of personal responsibility for the surgical patient. This strong history and tradition contribute to over a century of success prolonging and improving patients’ quality and length of life through operative intervention. However, despite a record of impressive surgical success, not all patients have good operative outcomes. Surgeons, arguably more than their non-surgical colleagues, are acutely aware and personally sensitive to the risks and complications inherent in the treatments they provide given the active role they assume in the provision of surgical therapy.(1–4)

Although this commitment to the surgical patient may be an essential component of care, in some settings surgeons’ personal responsibility may conflict with patients’ autonomy. For example, prior to the policy of required reconsideration, DNR orders were routinely suspended in the operating room suggesting that patient autonomy would not be honored if a cardiac arrest was the direct result of surgery or anesthesia.(5–7) Our work(8) and that of others(9, 10) suggest that this surgical paternalism is linked to the issue of error and responsibility and is founded in the unique relationship between surgeon and patient. Most of what is known about this reluctance to withdraw life-support in surgery is based on qualitative studies(1, 2, 11) and anecdotal reporting.(12, 13) It is unknown how frequently surgeons will override a patient’s or surrogate’s request for withdrawal of aggressive care and what factors influence this decision.

We used clinical vignettes to examine potential conflict between surgeon error and patient autonomy in the context of high-risk operations where unfortunate outcomes are not uncommon. Our use of vignettes allowed us to experimentally examine the role that operative timing and surgeon error may play in surgeons’ decisions to withdraw life-supporting therapy following an unwanted clinical outcome. We explicitly tested the association between surgeons’ personal responsibility and decisions to withdraw life-supporting therapy in the setting of a postoperative complication.

METHODS

Participants and incentives

We administered our survey to a randomly selected sample of Vascular, Cardiothoracic, and Neurosurgeons derived from membership lists of regional vascular surgery societies, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS) Cerebrovascular Section. We selected these subspecialties to maximize the likelihood that participants routinely performed high risk operations. We defined “high risk” throughout the survey as an operation with a procedural mortality greater than 1% or significant morbidity such as renal failure, major stroke, paralysis or ventilator dependence.

In March of 2010 we sent 2100 surveys, 700 per subspecialty group, to potential respondents. Each survey was packaged with a stamped return envelope and a laser-pointer pen valued at $2.85 as an incentive to encourage participation. A follow up survey with stamped return envelope was sent to all non-respondents. Due to a low response rate, a third survey was sent to non-responding neurosurgeons after verifying addresses through Internet searches. We then added 180 AANS members to replace individuals from the first cohort whose addresses could not be verified.

We used the American Association for Public Opinion (AAPO) guidelines to calculate our response rate.(14) First, all surveys that were returned to sender without survey response and all surveys completed by ineligible respondents such as junior residents and non-surgeons were removed. Next, we used an Internet search to estimate the percentage of non-respondents who were ineligible due to faulty contact information by verifying the contact information of 60 respondents, 20 from each subspecialty group, and 60 non-respondents. We combined this eligibility information according to the AAPO standards to calculate the adjusted response rate.

Survey Design

We designed a survey to elicit factors that may influence a surgeon’s decision to withdrawal life-supporting therapy postoperatively after a life altering complication. We first conducted a qualitative study to identify themes and trends regarding surgeons’ practices around the use of advance directives and withdrawal of life supporting therapy. We used semi-structured interviews of surgeons and other physicians who routinely care for patients having high risk operations. This study identified the importance of preoperative discussions, the influence of error and responsibility and personal investment in the surgical patient as important factors for postoperative decisions about life supporting therapy.(8, 15) Next, we developed survey questions to validate and generalize the results of our qualitative investigation.

We designed a vignette to assess surgeon response to a patient’s request to withdraw life-supporting therapy after a difficult postoperative complication. (Appendix) The vignette featured a specialty specific operation and we used a 2×2 between-subject factorial design to assess the associations of interest. (Table 1) Thus, each surgeon received one of four vignette versions that modified the timing of the case (elective vs. emergent) and the nature of the surgical complication (surgeon error vs. happenstance). Our primary variable of interest was the surgeon’s response to the patient’s request to withdraw life-supporting therapy. We asked respondents how likely they would be to withdraw therapy using a four-point Likert scale response frame (“Not at all Likely”, “Somewhat Unlikely”, “Somewhat Likely” and “Very Likely”). We also examined respondents’ likelihood of asking the patient to wait for a short period of time (3 days) or for a prolonged period (10 days) to revisit the question of withdrawal of life-support. To understand factors that contributed to the surgeon’s decision we directly assessed the influence of 10 distinct factors on the surgeon’s management of the patient’s request to withdraw aggressive therapy. These factors are listed in table 4 and include surgeon factors such as impact on performance measures and fear of litigation, institutional factors such as hospital resources invested in the patient’s care and patient factors such as the patient’s ability to accurately predict the value of future health states.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Clinical Vignettes Administered to Surgeons.

| Vascular | Cardiothoracic | Neurosurgical | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elective | Thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair | Ascending aortic aneurysm repair | Calcified right MCA aneurysm clipping |

| Emergent | Ruptured thoracoabdominal aneurysm repair | Emergency ascending aortic aneurysm repair for dissection | Calcified right MCA aneurysm clipping with a Fischer 3, Hunt and Hess grade II subarachnoid hemorrhage |

| Surgeon Error | During the operation surgeon inadvertently places the proximal clamp so that it occludes the left carotid artery and the patient has weakness in her right arm and leg when she awakes from anesthesia | During the operation surgeon inadvertently dislodges arterial cannula and patient has weakness in her right arm and leg when she awakes from anesthesia | Postoperative angiogram demonstrates that during the operation surgeon inadvertently caused ischemia from a third MCA branch that was accidently occluded by the clip tines |

| Not clearly surgeon error | Patient has an intra-operative stroke and weakness in her right arm and leg when she awakes from anesthesia | Patient has an intra-operative stroke and has weakness in her right arm and leg when she awakes from anesthesia | Patient has a dense left hemiparesis when she awakes from anesthesia; MRI confirms non-hemorrhagic stroke in the right internal capsule |

TABLE 4.

Association between Factors Impacting Decisions to Withdraw Life Supporting Therapy.

| Response to hypothetical vignette regarding whether or not life supporting therapy should be withdrawn | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factors “Somewhat” or “Very Important” influencing management of vignette patient | Favor withdrawing therapy (N=329), % | Favor not withdrawing therapy (N=557), % | P |

| Preoperative discussion with family | 97 | 94 | 0.08 |

| Impact on performance measures | 25 | 27 | 0.54 |

| Personal time and emotional commitment | 50 | 52 | 0.66 |

| Hospital resources invested in patient | 19 | 16 | 0.25 |

| Patient’s unknown prognosis | 70 | 70 | 0.97 |

| Personal optimism regarding patient’s future QOL | 62 | 79 | <0.0001 |

| Concern patient is unable to accurately predict value of future health state | 68 | 80 | <0.0001 |

| Personal feelings about morality of WD of LST | 16 | 31 | <0.0001 |

| Fear of litigation | 16 | 16 | 0.99 |

| Belief that as the patient’s surgeon you are ultimately responsible for her death | 31 | 33 | 0.54 |

The hypothetical vignette was piloted and pretested with 2 vascular surgeons, 1 neurosurgeon, and 1 cardiac surgeon for technical clarity and plausibility. In addition, all survey items were iteratively tested and modified using cognitive interviews with 6 surgeons who routinely perform high risk operations but did not practice vascular, cardiac or neurosurgery. The study was approved as exempt by Institutional Review Boards at the University of Wisconsin and the University of Chicago and included a waiver of written consent.

Analysis

We entered data using Microsoft Excel with a ten percent audit confirming that the accuracy of data entry was greater than 99%. We used descriptive statistics to examine the distribution of each variable. We defined our primary outcome as the surgeon’s response to the patient’s request for withdrawal of life supporting therapy. For this analysis, we dichotomized responses by comparing “Not at all Likely” and “Somewhat Unlikely” with “Somewhat Likely” and “Very Likely”. In sensitivity analyses, we examined the effect of different methods of categorizing this outcome variable, and findings were substantively unchanged using other methods of categorization. Next, we examined the bivariate association between the timing of the case, the nature of the surgical complication, surgeon cited factors, and the surgeon’s likelihood of honoring the patient’s request to withdraw life-supporting therapy. Finally, we conducted stepwise multivariate logistic regression to identify factors independently associated with surgeons’ decision to withdraw care. Our final models included the experimental variables of interest, basic demographic characteristics of respondents, and factors surgeons reported as influential in guiding their decision making that were of at least borderline significance (p<0.10) on bivariate analysis. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Participants

A total of 912 completed surveys were returned. The adjusted response rate was 56% for vascular surgeons, 54% for cardiac surgeons and 56% for neurosurgeons. A similar number of surveys was returned for each of the four randomly distributed vignettes. We found no significant difference in the willingness to withdraw life-supporting therapy between the early responders and the late responders to this survey, suggesting the absence of response-wave or non-response bias.

Nearly all surgeons reported performing at least one high risk procedure per month (mean=10.8, median=8). The respondents were evenly split between private practice and academic practices and represented a broad range of practice experience. (Table 2) In response to the vignette featuring a patient requesting withdraw of life supporting therapy, 63% of surgeons reported they were “Not at all” or “Somewhat unlikely” to withdraw life supporting therapy in this setting; 57% reported they were “Very Likely” or “Somewhat Likely” to wait 10 days to see if the patient’s condition improved.

TABLE 2.

Respondent Characteristics (N=912).

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Male gender | 850 (94) |

| Specialty | |

| Vascular | 327 (36) |

| Neurological | 273 (30) |

| Cardiovascular | 312 (34) |

| Practice setting | |

| Private practice | 376 (42) |

| Academic practice | 328 (37) |

| Private practice with academic affiliation | 182 (20) |

| Other | 8 (1) |

| Years in practice | |

| <10 | 187 (22) |

| 11–20 | 208 (25) |

| 21–30 | 229 (27) |

| >30 | 216 (26) |

| Number of high risk operations performed each month | |

| 0 | 34 (4) |

| 1–5 | 311 (34) |

| 6–10 | 256 (31) |

| 11+ | 238 (29) |

Factors influencing the decision to withdraw life supporting therapy

On bivariate analysis, surgeons who were told the patient’s complication was the result of surgeon error were significantly less likely to withdraw support than their colleagues who encountered a non-iatrogenic complication (33 vs. 41%, p = 0.008). Similarly, surgeons who had an elective operation were less likely to withdraw life-supporting therapy than those operating in an emergent setting (33 vs. 41%, p = 0.01). (Table 3) There were also differences in the likelihood of withdrawal of life-support based on several other surgeon characteristics. For example, cardiothoracic and neurosurgeons were significantly less likely to withdraw life-support than vascular surgeons (30 vs. 37 vs. 45%, respectively, p=0.0006). In addition, surgeons who were less likely to withdraw life-supporting therapy were more likely to report personal optimism about the patient’s future quality of life than their counterparts (79 vs. 62%, P< 0.0001). There was no difference in reported concern about performance measures between surgeons who withdrew and did not withdraw life supporting therapy (25 vs. 27%, p = 0.54). (Table 4)

TABLE 3.

Bivariate Association between Respondent and Vignette Characteristics and Withdrawal

| Characteristic | N | Percent withdrawing life supporting therapy |

Bivariate p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 830 | 38 | 0.90 |

| Female | 49 | 37 | |

| Subspecialty | |||

| Cardiothoracic | 307 | 30 | |

| Neurosurgery | 264 | 37 | 0.0006 |

| Vascular | 317 | 45 | |

| Years of experience | |||

| 0–10 | 193 | 42 | |

| 11– 20 | 213 | 39 | 0.22 |

| 21–30 | 228 | 36 | |

| 31–40+ | 214 | 33 | |

| Region | |||

| Midwest | 226 | 36 | |

| Northeast | 245 | 43 | 0.03 |

| South | 234 | 30 | |

| West | 158 | 40 | |

| Cause of complication | |||

| Surgeon Error | 427 | 33 | 0.008 |

| Not surgeon error | 461 | 41 | |

| Timing of surgery | |||

| Elective | 429 | 33 | 0.01 |

| Not elective | 459 | 41 | |

| Cause and timing | |||

| Surgeon error/Elective | 208 | 29 | |

| Surgeon error/Not elective | 221 | 36 | 0.004 |

| Not surgeon error/Elective | 219 | 36 | |

| Not surgeon error/Not elective | 240 | 45 | |

On multivariate analyses, a strong and statistically significant association persisted between surgical timing, the surgeon’s role in the poor outcome, and willingness to withdraw life-support. The odds of withdrawing life-sustaining therapy were nearly two-fold as great among surgeons who encountered a complication that was not clearly the result of surgeon error during an emergency operation than among surgeons encountering a complication from surgeon error in the elective setting (odds ratio [OR]=1.95, 95% confidence intervals [CI] 1.26–3.01). In addition, the odds of withdrawing life-support were greater among those who did not express optimism about the patient’s future quality of life (OR=1.75, CI 1.11–2.50) and among those who were less concerned that the patient did not accurately value her future health state (OR 1.59, CI 1.11–2.27) than among their counterparts. (Table 5)

TABLE 5.

Multivariate Logistic Regression of Surgeon and Operative Factors Associated With Withdraw of Life Supporting Therapy

| Odds ratio (95% confidence intervals) |

|

|---|---|

| CASE FACTORS | |

| Iatrogenic/Elective | Ref |

| Iatrogenic/Emergent | 1.34 (0.86–2.11) |

| Not iatrogenic/Elective | 1.37 (0.88 – 2.12) |

| Not Iatrogenic/Emergent | 1.95 (1.26 – 3.01) |

| SURGEON FACTORS | |

| Specialty | |

| Cardiothoracic | Ref |

| Neurosurgery | 1.29 (0.87 – 1.90) |

| Vascular | 1.72 (1.81 – 2.52) |

| Years of experience | |

| 30+ | Ref |

| 21 – 30 | 1.05 (0.68 – 1.61) |

| 11 – 20 | 1.43 (0.92 – 2.20) |

| 0 – 10 | 1.50 (0.96 – 2.36) |

| Region | |

| South | Ref |

| Midwest | 1.23 (0.79 – 1.91) |

| Northeast | 1.64 (1.07 – 2.54) |

| West | 1.47 (0.92 – 2.35) |

| Somewhat or very important factors influencing decision making | |

| Pre-operative conversations | 2.00 (0.91 – 4.4) |

| Optimism about patient’s future quality of life | 0.57 (0.40 – 0.80) |

| Concern patient cannot accurately predict value of future health state | 0.63 (0.44 – 0.90) |

| Morality of withdrawing life supporting therapy | 0.51 (0.35 – 0.75) |

DISCUSSION

In this national study of surgeons, those faced with complication from surgical error during an elective operation were substantially less likely to withdraw life supporting therapy than those managing a patient where a complication was not clearly from error and occurred in the setting of an emergency operation. Optimism about the patient’s future quality of life and concern for the patient’s ability to accurately predict her future health state were both associated with a surgeon’s decision to delay withdrawal of postoperative life-support.

These findings are important because high risk operations are performed frequently and little is known about the complex factors that influence the management of complications and requests for withdrawal of life-supporting therapy. Surgeons who feel responsible for the life of their patient and the role that they played in an unwanted outcome have difficulty relinquishing the goal of patient survival. Patients and other providers unaware of the surgeon’s error and feelings of responsibility may then struggle to understand the surgeon’s inability to change course and reconsider clinical goals. In The Silent World of Doctor and Patient, Jay Katz notes that “…physicians and patients bring their own vulnerabilities to the decision-making process. Both are authors and victims of their own conflicting motivations, interests and expectations.” (16) Our findings demonstrate that in the setting of an unwanted postoperative outcome, a surgeon’s emotion and accountability have inevitable clinical consequences for both surgeons and patients.

For surgeons, these data suggest that non-clinical factors may influence decision making about withdraw of life supporting therapy. Ours is not the first study to suggest the importance of non-clinical factors that influence clinical decision-making; there is a large body of literature demonstrating how non-clinical patient characteristics, as well as features of physicians and structural aspects of care, may affect health care delivery.(17–20) However, our study is unique in its examination of high risk operations and the role that technical performance may play in guiding the management of postoperative life supporting therapies. Iatrogenic complications that clearly derive from technical error during elective operations may pose considerable guilt and emotional burden upon surgeons.(21–23) It is understandable that such factors should weigh on the surgeon. However, our findings call into question the degree to which these factors may unduly interfere with a patient’s ability to control his or her health care decisions.(24, 25)

For patients and their families, these data suggest that surgeons who prognosticate in the setting of an elective operation complicated by technical error may be providing information that is overly influenced by an emotional response to the clinical situation rather than an unbiased interpretation of the relevant clinical data. Indeed physicians’ subjective impressions about survival may have more impact on the decision to withdraw support in the critically ill patient than validated predictive models(26, 27) and physicians’ tendency to be overly optimistic regarding the prognosis of terminally ill patients has been well described.(28) Our data suggest that commission of an error in surgical technique and prognostic optimism may present a challenge to patient autonomy. Particularly in settings where there is disagreement between patients and their families and the treating physician, our findings highlight the importance of frank discourse and, when needed, consultation with other disinterested parties in order to navigate what may be difficult postoperative decision-making.

Recognition that the surgeon’s emotional state may have a significant impact on patients’ postoperative management also suggests the importance of efforts to alleviate surgeons’ emotional strain while simultaneously respecting the fierce ethic of responsibility that surgeons possess for patients’ outcomes.(1) While surgical Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) Conferences may be a forum for catharsis and education surrounding technical error, there are few, if any, other formal venues for surgeons to express the emotional burden of caring for the surgical patient.(22, 29–31) Furthermore, while efforts to improve quality and outcomes in surgery are essential, the goals of quality improvement should be distinct from the intrinsic goals of surgical therapy and from the value of the surgeon-patient relationship. The performance of an operation in order to save or improve quality of life is valuable to patients and their families even when the patient doesn’t survive.

Our study had several limitations. First, as with all surveys, our findings may be subject to non-response bias. However, we did not find any evidence of response wave bias, and since our hypothetical vignette used an experimental design, it is unlikely that our main findings would be substantively affected by such bias. Second, we focused on Vascular, Cardiothoracic, and Neurosurgeons because of how commonly they perform high risk operations. Although our findings may not be generalizable to surgeons in other fields such as general surgery or non-thoracic surgical oncology, we have no reason to believe otherwise. Third, our study design necessarily used a hypothetical vignette so that operative characteristics could be experimentally altered. Although vignettes cannot capture the complexity present in a real clinical case, evidence supports their use to examine physicians’ clinical decision-making.(32)

In conclusion, when a patient suffers a life threatening complication and requests withdrawal of life-supporting therapy postoperatively, surgeons may be unlikely to withdraw life supporting therapy without delay. These decisions are influenced by both the timing of surgery and whether the complication was the result of explicit technical error. In addition, these non-clinical factors may be associated with surgeons’ optimism about the patient’s postoperative quality of life. Future efforts to enhance shared decision making for critically ill surgical patients need to address non-clinical biases that influence decision making in the setting of surgical complications.

Figure.

Percentage of Surgeons Who Would Withdraw Life Support at the Time of Patient Request as Influenced by Vignette Characteristics

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Layton Rikkers and Michelle Mello for their thoughtful review of this manuscript. In addition, we appreciate the work of Glen Leverson and Ann Chodara for assistance with statistical analysis and data management.

Funding

Dr. Schwarze is supported by a Greenwall Faculty Scholars Award and the Department of Surgery at the University of Wisconsin. Mr. Redmann is supported by a Shapiro Summer Research Award from the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. Dr. Alexander is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (RO1 HS0189960). These funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript for publication.

APPENDIX

Hypothetical Vignette Administered to Surgeons.*

| You perform a (specialty specific operation performed electively or emergently) on a 75 year-old woman with emphysema and stable coronary artery disease. She has an intra-operative stroke and weakness in her arm and leg when she awakes from anesthesia. (insertion of iatrogenic injury here) Her post-operative status is tenuous and she has been re-intubated twice. After 7 days in the intensive care unit she has developed pneumonia and requires ventilatory support. She is alert and has the capacity to make decisions about her medical therapy. The patient and her family request withdrawal of life supporting therapy stating that her future quality of life is unacceptable and that she would rather be allowed to die. |

See Table 1 for experimental manipulations administered to survey participants

REFERENCES

- 1.Bosk CL. Forgive and Remember. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1979. Introduction; pp. 2–34. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cassell J, Buchman TG, Streat S, Stewart RM. Surgeons, intensivists, and the covenant of care: administrative models and values affecting care at the end of life--Updated. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(5):1551–1557. discussion 7–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerber LA. Transformations in self-understanding in surgeons whose treatment efforts were not successful. Am J Psychother. 1990;44(1):75–84. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1990.44.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larochelle MR, Rodriguez KL, Arnold RM, Barnato AE. Hospital staff attributions of the causes of physician variation in end-of-life treatment intensity. Palliat Med. 2009;23(5):460–470. doi: 10.1177/0269216309103664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burns JP, Edwards J, Johnson J, Cassem NH, Truog RD. Do-not-resuscitate order after 25 years. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(5):1543–1550. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000064743.44696.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen CB, Cohen PJ. Do-not-resuscitate orders in the operating room. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(26):1879–1882. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112263252611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wenger NS, Greengold NL, Oye RK, Kussin P, Phillips RS, Desbiens NA, et al. Patients with DNR orders in the operating room: surgery, resuscitation, and outcomes. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. J Clin Ethics. 1997;8(3):250–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwarze ML, Bradley CT, Brasel KJ. Surgical "buy-in": the contractual relationship between surgeons and patients that influences decisions regarding life-supporting therapy. Crit Care Med. 38(3):843–848. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cc466b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosk CL. Conclusion. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1979. pp. 168–192. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buchman TG, Cassell J, Ray SE, Wax ML. Who should manage the dying patient?: Rescue, shame, and the surgical ICU dilemma. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194(5):665–673. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01157-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz P. The Scalpel's Edge. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1999. The Surgeon as Hero; pp. 19–35. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tulsky JA. Beyond advance directives: importance of communication skills at the end of life. JAMA. 2005;294(3):359–365. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belanger S. Check your advance directive at the door: transplantation and the obligation to live. Am J Bioeth. 2010;10(3):65–66. doi: 10.1080/15265160903581809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 7th ed. AAPOR; 2011. The American Association for Public Opinion Research. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bradley CT, Brasel KJ, Schwarze ML. Physician attitudes regarding advance directives for high-risk surgical patients: a qualitative analysis. Surgery. 2010;148(2):209–216. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz J. The Silent World of Doctor and Patient. 3 ed. Baltimore: The John's Hopkins University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Redelmeier DA, Rozin P, Kahneman D. Understanding patients' decisions. Cognitive and emotional perspectives. JAMA. 1993;270(1):72–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dale W, Hemmerich J, Ghini EA, Schwarze ML. Can induced anxiety from a negative earlier experience influence vascular surgeons' statistical decision-making? A randomized field experiment with an abdominal aortic aneurysm analog. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(5):642–652. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cykert S, Dilworth-Anderson P, Monroe MH, Walker P, McGuire FR, Corbie-Smith G, et al. Factors associated with decisions to undergo surgery among patients with newly diagnosed early-stage lung cancer. JAMA. 2010;303(23):2368–2376. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):273–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott SD, Hirschinger LE, Cox KR, McCoig M, Brandt J, Hall LW. The natural history of recovery for the healthcare provider "second victim" after adverse patient events. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(5):325–330. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.032870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sirriyeh R, Lawton R, Gardner P, Armitage G. Coping with medical error: a systematic review of papers to assess the effects of involvement in medical errors on healthcare professionals' psychological well-being. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(6):e43. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.035253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christensen JF, Levinson W, Dunn PM. The heart of darkness: the impact of perceived mistakes on physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(4):424–431. doi: 10.1007/BF02599161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Casarett D, Ross LF. Overriding a patient's refusal of treatment after an iatrogenic complication. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(26):1908–1910. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199706263362611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Casarett DJ, Stocking CB, Siegler M. Would physicians override a do-not-resuscitate order when a cardiac arrest is iatrogenic? J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(1):35–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.00278.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barnato AE, Angus DC. Value and role of intensive care unit outcome prediction models in end-of-life decision making. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20(3):345–362. vii–viii. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook D, Rocker G, Marshall J, Sjokvist P, Dodek P, Griffith L, et al. Withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in anticipation of death in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(12):1123–1132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christakis NA, Lamont EB. Extent and determinants of error in doctors' prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2000;320(7233):469–472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutter MM, Rowell KS, Devaney LA, Sokal SM, Warshaw AL, Abbott WM, et al. Identification of surgical complications and deaths: an assessment of the traditional surgical morbidity and mortality conference compared with the American College of Surgeons-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(5):618–624. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gore DC. National survey of surgical morbidity and mortality conferences. Am J Surg. 2006;191(5):708–714. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bosk CL. Forgive and Remember. 2 ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1979. The Legitimation of Attending Authority; p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peabody JW, Luck J, Glassman P, Dresselhaus TR, Lee M. Comparison of vignettes, standardized patients, and chart abstraction: a prospective validation study of 3 methods for measuring quality. JAMA. 2000;283(13):1715–1722. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.13.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]