Abstract

Study design: Systematic review.

Objectives: (1) Does brace treatment compared with observation of curves lead to lower rates of surgery and failure for patients with idiopathic scoliosis? (2) Does brace treatment compared with observation of curves lead to better quality of life outcomes for patients with idiopathic scoliosis? (3) Does brace treatment compared with observation of curves lead to improved curve angle for patients with idiopathic scoliosis?

Methods: A systematic review of the English-language literature was undertaken for articles published between 1970 and December 2010. Electronic databases and reference lists of key articles were searched to identify studies comparing brace treatment with observation of curves in patients with idiopathic scoliosis. Two independent reviewers assessed the strength of evidence using the GRADE criteria assessing quality, quantity, and consistency of results. Disagreements were resolved by consensus.

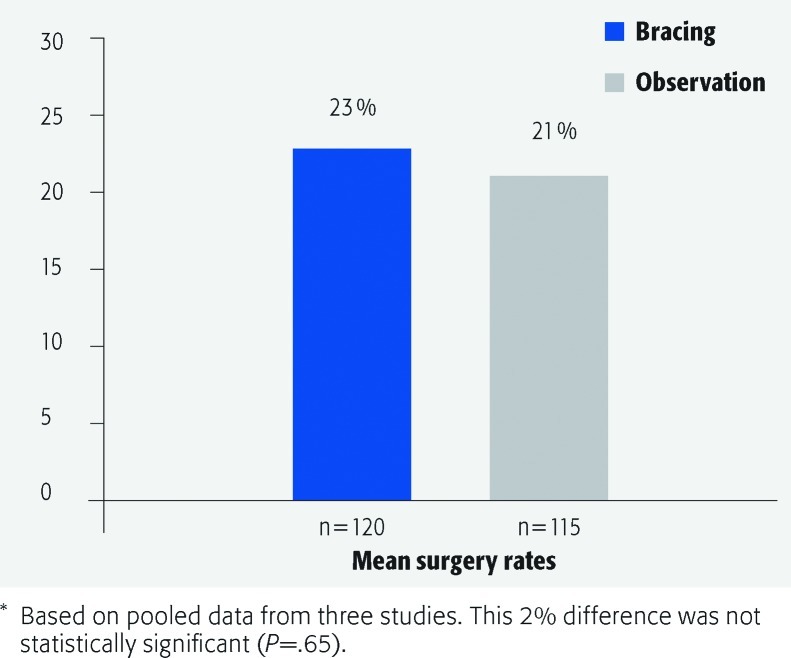

Results: We identified eight studies meeting our inclusion criteria. The pooled studies comparing surgical rates between observation and brace treatment showed no statistical significance (P = .65). One study showed a statistically significant difference in failure rate between observation (45%) and brace (15%) treatment (P < .001). Findings with respect to posttreatment quality of life at 2 years were inconsistent. Two studies favored the brace group, and one the observation group using the SRS-22 and Quality of Life Profile for Spine Deformities (QLPSD) measures. Two of three studies reporting pretreatment and posttreatment curve angles demonstrated a treatment effect favoring bracing; however, statistical significance for these treatment effects could not be calculated. One study described a treatment effect favoring observation but the differences were not statistically significant (P = .26).

Conclusion: This systematic review identified and summarized only the highest level of evidence by limiting to comparison studies. Case-series were not included. This allowed for comparisons among the same patient populations. Findings with respect to surgical rates, quality of life, and change in curve angle demonstrate either no significant differences or inconsistent findings favoring one treatment or the other. If bracing does not cause a positive treatment effect, then its rejection will lead to significant savings for healthcare providers and purchasers. Given the very low to low level of evidence and inconsistent findings, a randomized trial is necessary to determine if bracing should be recommended.

Study Rationale and Context

Bracing of patients with idiopathic scoliosis remains an evocative subject. There are strong advocates and skeptics. The aim of bracing is to prevent curve deterioration and surgical intervention. However, it is still a treatment that can adversely affect the individual patient. Often, a patient with a small curve may have a spinal deformity unrecognizable to their friends and peer group. This occurs at a time for most patients when appearing different can lead to significant negative consequences. Bracing in itself may create an illness behavior. By making the problem more visible this may highlight the condition to other individuals. The negative result of a brace can be offset if its clinical effect causes a treatment outcome that stops major surgical intervention and risk exposure. However, if the brace does not prevent surgery or curve progression then the economic costs to society and the negative psychological and social effects of wearing a brace cause a morbidity that should be avoided.

There has been little done in the way of systematic reviews using only high-level evidence studies or meta-analyses comparing brace treatment with observation in the past. Several systematic reviews have compared bracing with observation.1,2,3 Negrini et al1 only included two studies; one comparing brace treatment to observation and one comparing two different brace types. They concluded that there was very low quality of evidence supporting brace treatment. Weiss and Goodall2 compared several different treatments—physical therapy, inpatient rehabilitation, bracing, and surgery to the natural history of idiopathic scoliosis. They concluded that there was some evidence of a better scientific standard supporting inpatient rehabilitation and bracing for the treatment of idiopathic scoliosis. Finally, Lenssinck et al3 compared various conservative treatments, such as bracing, electrical stimulation, and exercise. They concluded that because of the low-level quality studies, it is hard to draw firm conclusions. However, the effectiveness of bracing is promising, but not yet established. In one meta-analysis, Rowe et al4 compared different kinds of bracing with electrical stimulation and observation. However, only one study with observation was included. All other studies compared different types of braces and electrical stimulation. Their conclusions support the effectiveness of bracing for treating idiopathic scoliosis. None of the previous systematic reviews included surgical rates, failure rates, curve-angle changes, and patient-centered quality of life (QoL) outcomes together in the same review. Therefore, our aim was to compare brace treatment with observation only with respect to all these measures in the treatment of idiopathic scoliosis.

Objectives

(1) Does brace treatment compared with observation of curves lead to lower rates of surgery and failure for patients with idiopathic scoliosis? (2) Does brace treatment compared with observation of curves lead to better QoL outcomes for patients with idiopathic scoliosis? (3) Does brace treatment compared with observation of curves lead to improved curve angle for patients with idiopathic scoliosis?

Materials and Methods

Study design: Systematic review.

Sampling:

Search: PubMed, Cochrane collaboration database, and National Guideline Clearinghouse databases; bibliographies of key articles.

Dates searched: 1970–December 2010.

Inclusion criteria: Patients with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and nonrandomized comparison studies.

Exclusion criteria: Scoliosis from any other causes; adult patients; adjunct treatments such as electrical stimulation; case-series and studies with historical controls.

Outcomes: Surgery rates, failure rates, QoL, and curve-angle changes.

Analysis: Descriptive statistics. Study-level surgical rate data was combined to calculate pooled surgical rates and risk differences (between the two groups) with 95% confidence intervals. Change scores for studies reporting pretreatment and posttreatment QoL and curve angles were computed. Treatment effects (ie, effects of bracing versus observation) were calculated by subtracting change scores. Data could not be pooled due to the heterogeneity of outcome measures and absence of preoperative and postoperative standard deviations.

Details about methods can be found in the web appendix at www.aospine.org/ebsj.

Results

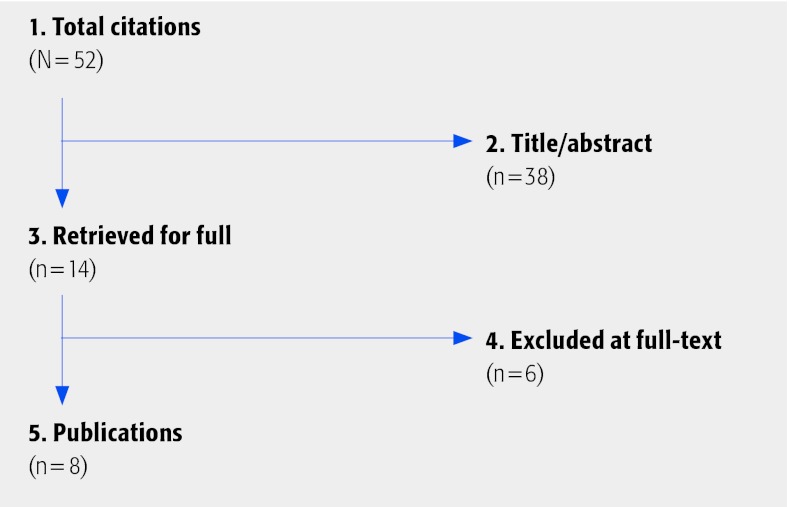

Fifty-two potential articles were identified from our initial search code. Thirty-eight studies were excluded at title or abstract and 14 were pulled for full-text review. Six of these studies were excluded. Three studies contained historical controls groups (ie, groups were not compared during the same period). Three studies contained cohorts comparing different brace types but they did not compare a brace treatment group with an observation group. We identified eight studies5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 meeting our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). No randomized controlled trial comparing brace treatment with observation was identified. All eight studies were nonrandomized studies comparing brace treatment with observation of curves. Details of each study can be found in Table 1,Table 2,Table 3,Table 4.

Fig. 1.

Results of literature search.

Table 1. Characteristics of cohort studies in an idiopathic scoliosis population comparing bracing with observation.

| Reference | Study design | Study population | Bracing | Observation | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nachemson and Peterson (1995)5 | Prospective cohort April 1985–March 1989 |

N = 240

|

n = 111

|

n = 129

|

Failure rate defined as an increase in the curve of at least 6° |

|

Danielsson et al. (2007)

6 Subpopulation of Nachemson |

Prospective cohort April 1985–March 1989 |

N = 92

|

n = 35

|

n = 57

|

Surgery rate at 16 y after maturity |

| Fernandez-Feliberti et al. (1995)7 | Retrospective cohort 1982–1990 |

N = 101

|

n = 54/69

|

n = 47 (indicated for TLSO, but never used)

|

Surgery rate Cobb angle < 40° |

| Cheung et al. (2007) 8 | Retrospective cohort December 1990 |

N = 92

|

N = 46

|

n = 46

|

SRS-22 questionnaire |

| Parent et al (2009) 9 | Prospective cohort April 2004–May 2005 |

N = 139

|

n = 32

|

n = 107

|

SRS-22 questionnaire |

| Mannherz et al. (1988)10 | Retrospective cohort 1940–1986 |

N = 43

|

n = 31/32 (1 patient refused brace)

|

n = 11

|

Surgery rate |

| Pham et al. (2008)11 | Prospective cohort | N = 73

|

n = 41

|

n = 32

|

Quality of Life Profile for Spine Deformities (QLPSD) Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain and quality of life |

| Ugwonali et al. (2004)12 | Prospective cohort | N = 214

|

N = 78

|

N = 136

|

Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ) Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument (PODCI) |

Table 2. Subject characteristics of studies evaluating brace treatment versus observation for the treatment of idiopathic scoliosis.

| Bracing, N = 231 | Observation, N = 244 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Studies, n | Patients, n | Results, mean | Results, range | Studies, n | Patients, n | Results, mean | Results, range |

| Surgical rates | 36,7,10 | 120 | 23% | 0%–42% | 36,7,10 | 115 | 21% | 0%–38% |

| Failure rates* | 15 | 111 | 15% | 15% | 15 | 129 | 45% | 45% |

Defined as an increase in the curve of at least 6°, demonstrated on two consecutive x-rays.

Table 3. Characteristics of studies using Quality of Life (QoL) as an outcome in patients with idiopathic scoliosis treated with bracing or observation.

| Reference | QoL measure | Domains | Brace Mean |

Observation Mean |

P value | Measure interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cheung et al.(2007)8 | SRS-22 questionnaire | Function/activity | 4.53 | 4.89 | .00007 |

|

| – Self-image | 3.63 | 4.04 | .0007 | |||

| – Pain | 4.62 | 4.65 | .7 | |||

| – Mental health | 4.31 | 4.50 | .1 | |||

| – Satisfaction | 3.90 | 3.98 | .6 | |||

| Total score | 4.24 | 4.47 | .005 | |||

| Parent et al. (2009)9 | SRS-22 questionnaire | Function/activity | 4.5 ± 0.59 | 4.3 ± 0.59 | .09 |

|

| – Self-image | 3.6 ± 0.72 | 3.6 ± 0.73 | 1.0 | |||

| – Pain | 4.3 ± 0.78 | 3.9 ± 0.78 | .01 | |||

| – Mental health | 4.0 ± 0.71 | 3.9 ± 0.71 | .49 | |||

| – Satisfaction | 4.0 ± 0.85 | 3.5 ± 0.85 | .004 | |||

| Total score | 4.1 ± 0.54 | 3.9 ± 0.54 | .07 | |||

| Pham et al. (200)11 | Quality of Life Profile for Spine Deformities (QLPSD) | Psychosocial functioning | 13 | 9 | <.001 |

|

| – Sleep disturbance | 9.5 | 7 | <.001 | |||

| – Back pain | 8 | 6.25 | .122 | |||

| – Body image | 8.25 | 6 | <.01 | |||

| – Back flexibility | 9.25 | 4 | <.001 | |||

| Total score | 48 | 32.25 | <.001 | |||

| Ugwonali et al. (2004)12 | Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ) |

Physical functioning | 92.7 | 94.2 | .57 |

|

| – Bodily pain | 76.3 | 78.6 | .58 | |||

| – Behavior | 84.0 | 82.0 | .31 | |||

| – Mental health | 84.5 | 84.7 | .93 | |||

| – Self-esteem | 85.4 | 85.3 | .96 | |||

| – General health | 77.6 | 81.3 | .15 | |||

| – Emotional/ behavioral limits | 98.3 | 98.0 | .86 | |||

| – Physical limits | 97.0 | 97.0 | .97 | |||

| – Parental impact-emotional | 71.7 | 76.5 | .16 | |||

| – Parental impact-time | 93.6 | 95.3 | .43 | |||

| – Family activities | 95.9 | 94.5 | .41 | |||

| – Family cohesion | 81.9 | 80.3 | .58 | |||

| Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument (PODCI) | – Upper extremity and physical function | 98.0 | 98.8 | .18 |

|

|

| Transfers and basic mobility | 99.1 | 99.3 | .70 | |||

| Sports and physical function | 94.3 | 95.9 | .09 | |||

| – Pain/comfort | 88.2 | 91.9 | .16 | |||

| – Happiness | 90.1 | 89.3 | .72 | |||

| Expectations | 79.2 | 65.2 | .02* | |||

| Global function/symptoms | 95.0 | 96.9 | .04* |

These differences disappeared with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Items in bold represent statistically significant associations.

Table 4. Characteristics of studies using curve angle as an outcome in patients with idiopathic scoliosis treated with bracing or observation.

| Reference | Pretreatment curve bracing (B) | Pretreatment curve observation (O) | Posttreatment curve (B) | Posttreatment curve (O) | Change* | Treatment effect† or risk difference (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (B) | (O) | ||||||

| Danielsson et al. (2007)6 | Cobb angle: 31.8°‡ (26–38°) |

Cobb angle: 29.5°‡ (23–39°) |

Cobb angle: 26.4°‡ (14–37°) |

Cobb angle: 29.9°‡ (10–42°) |

−5.4° | +0.4° | −5.0° |

| Fernandez-Feliberti et al. (1995)7 | Cobb angle ≤ 29°: 25/54 (46.3%) Cobb angle ≥30°: 29/54 (53.7%) |

Cobb angle ≤ 29°: 27/47 (57.5%) Cobb angle ≥ 30°: 20/47 (42.5%) |

Cobb angle ≤ 39°: 38/54 (70.4%) Cobb angle ≥ 40°: 16/54 (29.6%) |

Cobb angle ≤ 39°: 28/47 (59.6%) Cobb angle ≥ 40°: 19/47 (40.4%) |

NA | NA | Risk difference −10.7% (95% CI: −.08–.29; P = .26§) |

| Mannherz et al. (1988)10 | Cobb angle: 22° (10–40°) |

Cobb angle: 11° (10–15°) |

Cobb angle: 29° (0–40°) |

Cobb angle: 8° (0–25°) |

+7.0° | −3.0° | +4.0° |

| Pham et al.†(2008)11 | Cobb angle: 30.5°‡ ± 3.1 |

Cobb angle: 26.5°‡ ± 2.4 |

Cobb angle∥: 17.8°‡ |

Cobb angle∥: 26.5°‡ |

−12.7 ± 2.3 | 0° | −12.7° |

P values for change scores could not be calculated from raw data. NR indicates not reported; NA, not applicable.

Treatment effect is difference in change scores. Negative favors bracing; positive favors observation. Confidence intervals (CI) could not be calculated because standard deviations were not reported by the authors. Data between studies could not be pooled for this reason. Risk difference = Bracing - Observation (rates > 40°). A negative number suggest a smaller failure rate for bracing.

The pre-curve and post-curve angles were statistically significant.

Risk difference is not statistically significant; however, bracing group included patients with more severe baseline curves. This is not accounted for in the analysis. Part-time bracing group (not included in analysis) had an 11.0° ± 2.7 improvement.

Calculated from change scores.

Surgery rates comparing brace treatment with observation of curves (Table 2 and Fig. 2)

Fig. 2.

Mean surgery rates comparing brace treatment with observation.*

Failure rates comparing brace treatment with observation of curves

One study defined failure rate as an increase in curve of at least 6° from the time of first x-ray, on two consecutive x-rays.5

The failure rate was 15% and 45% after brace and observation, respectively. The risk difference was 30% (95% confidence interval, 0.19–0.41; P < .001).

QoL outcomes comparing brace treatment with observation of curves

Four studies8,9,11,12 were identified that reported some type of QoL outcome (Table 3). None of these studies reported preoperative scores, so we could not calculate and compare treatment effects between groups based on change scores. Only postoperative scores were reported which may be confounded by the baseline scores.

Two studies compared brace with observation using the SRS-22 questionnaire. In Cheung et al study,8 the overall score favored the observation group (4.47 versus 4.24 points, respectively; P = .005) (Table 3). In contrast, there was no significant difference in overall score in the Parent et al study;9 however, the brace group was favored in the pain and satisfaction sub-domains (Table 3).

The study by Pham et al11 demonstrated the greatest difference in postoperative QoL scores using the Quality of Life Profile for Spine Deformities (QLPSD) in favor of the brace group (48 versus 32.25 points; respectively; P < .001). Few differences in QoL were observed in the study by Ugwonali et al,12 with the exception of small differences in expectations in favor of the brace and global function/symptoms in favor of observation (Table 3).

Curve-angle change comparing brace treatment with observation of curves

Four studies6,7,10,11 reported curve-angle outcomes. Three of the four reported pretretament and posttreatment angles or degrees of correction;2,6,7 however, only one study reported standard deviations so data could not be pooled nor could standardized mean differences be calculated. One study reported postoperative rates of patients who developed curve angles ≥40° which the authors considered a failure.3

Two of the three studies reporting pretreatment and posttreatment curve angles demonstrated a treatment effect favoring bracing;6,11 however, statistical significance for these treatment effects could not be calculated. One study reported a treatment effect favoring observation.10 The study that evaluated rates of curve-angle failure favored the bracing group (risk difference = 10.7%; P = .26).7 This difference was not statistically significant; however, baseline curves in the bracing group were on average more severe than the observation group. This was not accounted for in the analysis.

Evidence Summary

| Outcomes | Strength of evidence | Conclusions/comments |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Surgery rates |

|

|

| 2. Failure rates |

|

|

| 3. Quality of life |

|

|

| 4. Curve changes |

|

Discussion

No randomized controlled trials were identified in the literature making a comparison between bracing and observation as to wether bracing reduces surgical interventions. While valid comparisons and conclusions can be made from nonrandomized comparison studies, greater care must be taken in interpreting the results. The greatest threat to these studies is selection bias (ie, one group that is more or less severe across studies). However, these studies did not control for important baseline differences to ensure confounding was not present. Further, the baseline scores for QoL outcomes were not reported and therefore a change in QoL could not be calculated. Change in QoL is the most valid measure (compared with outcome score only), especially when groups may differ at baseline. Curve-angle treatment effects may have favored the bracing group; however, statistical significance of differences could not be calculated due to lack of raw data and/or baseline differences were not controlled for.

Bracing seems an attractive nonoperative treatment for patients with idiopathic scoliosis. It makes clinicians believe they are treating the condition without major intervention and makes parents feel that their children are being treated. However, even if the clinical effect of bracing is minimal, the impact on the patient for wearing a brace, multiple hospital attendances as well as the negative social and psychological effects need to be considered before subjecting a patient to this treatment.

We are aware that even if braces are prescribed the compliance with brace wearing is variable. It could be argued that if compliance was better then bracing would be more effective. Yet if the treatment compliance is so poor then its effectiveness should still be considered poor.

If bracing does not cause a positive treatment effect then its rejection will lead to significant savings for health care providers and purchasers.

If bracing does work and prevents patients having surgical procedures then this should lead to significant cost savings for society.

Given the poor scientific evidence currently available, bracing should probably only be considered if patients are involved in a randomized controlled trial to confirm its efficacy.

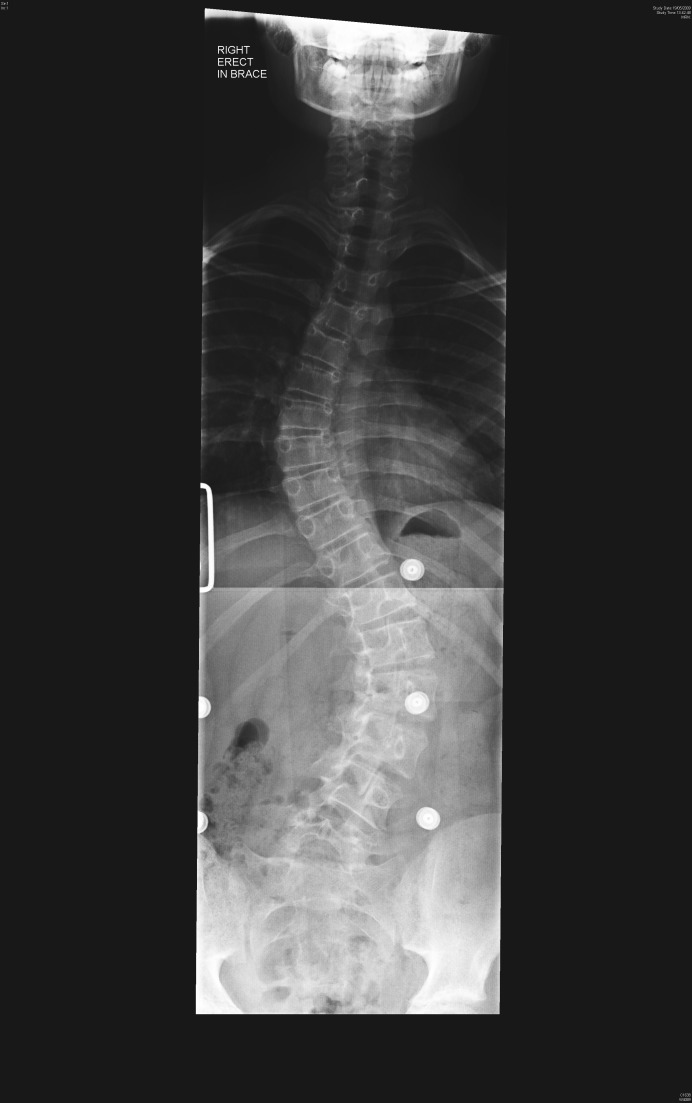

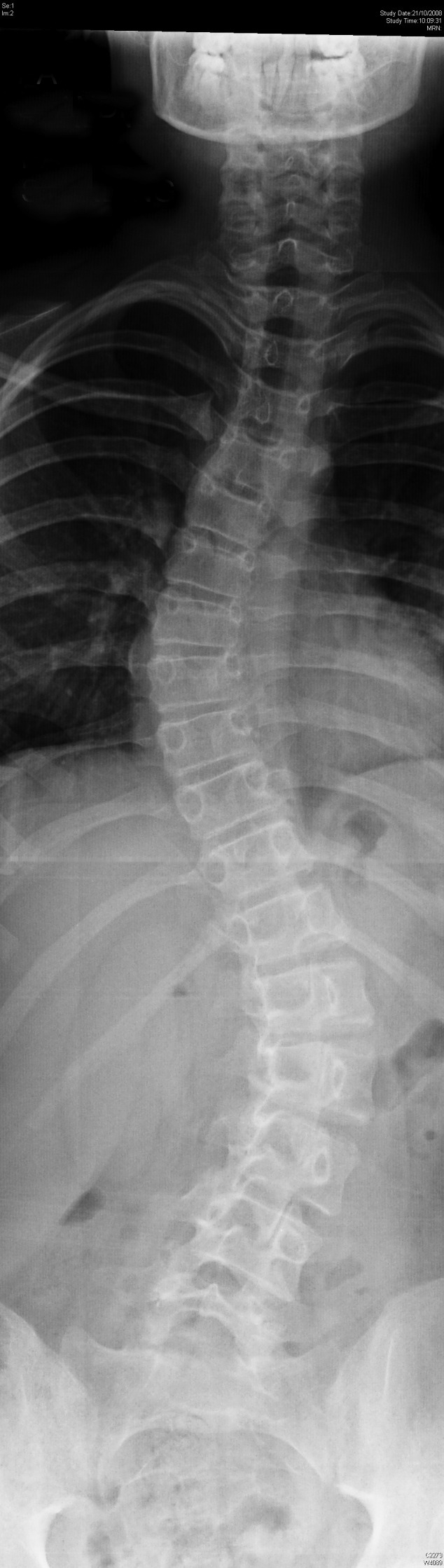

Illustrative Case

This set of x-rays (Fig. 3,Fig. 4,Fig. 5,Fig. 6,Fig. 7,Fig. 8) demonstrates curve progression in a patient with idiopathic scoliosis who was extremely compliant with brace wearing. She initially presented at 13 years old and during a 2-year period she was braced in a Boston Brace. The curve progressed during that time to a more complex double curve that required a more significant intervention to correct the curve surgically.

Fig. 3.

Patient aged 13 years. No treatment.

Fig. 4.

Patient aged 13 years; at 6 mths, progression and start bracing.

Fig. 5.

Patient aged 14 years; bracing.

Fig. 6.

Patient aged 14 years; at 6 months, bracing.

Fig 7.

Patient aged 15 years; bracing.

Fig. 8.

Patient aged 15 years; at 6 months, decision for surgery.

Footnotes

This systematic review was funded by AOSpine.

Editorial Perspective

The reviewers found the article interesting and relevant but noted that there had been previous attempts at meta-analysis, most recently in Lancet 2008 by S Weinstein et al1 using the Cochrane review and Medline from 1996–2006 and by Sponseller in 2011.2 It should, however, be noted that the Weinstein systematic review is primarily a summary of case series from both treatment arms that reduces the level of evidence of their findings substantially.

Only one of the studies (Fernandez-Feliberti, 1995) used in the systematic review by Weinstein1 was also used in the published EBSJ systematic review, which includes 8 articles: Mannherz (1988}; Nachemson (1995); Fernandez-Feliberti (1995); Ugwonali (2004); Cheung (2006); Pham (2008); Danielsson (2007); Parent (2009).

In addition, the Weinstein article1 consisted of a review of surgical techniques versus bracing without mention of observation only. As to the Sponseller article.2, its creation coincided with the writing of the present EBSJ article. Its main focus was aimed at identifying consensus for indications for bracing.

The reviewers concur with the EBSJ authors' conclusion that the evidence for bracing in the treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is—at best—marginal. Despite a literal explosion of publications on the subject of AIS in the general literature and a steadily growing body of studies in the orthopaedic literature there remains a paucity of clarity. There are two current well-funded and well-controlled prospective trials under way in North America, but it will likely be many years before any conclusions can be reached.

Are there then patients well suited for bracing using a best practices standard? The present EBSJ systematic review was not designed to provide any directed help in this regard.

Sponseller in his recent review suggests that patients with AIS curves between 25 to 45 degrees during their Risser 0 to 1 status should be considered for initial bracing.2 He goes on to suggest that patients of Risser scores 2 or 3 and curves of 30–45 degrees may be offered bracing on their initial visits.

This recommendation, however, is again tempered by questions surrounding the reliability of the Risser sign, thus limiting the validity of these recommendations. Patient compliance with brace wear and brace acceptance remains another important variable, which cannot be fully accounted for despite technological advances, such as thermal scanners and electrical impedance measuring devices.

Finally, the reviewers noted that the authors of the EBSJ systematic review touched upon, but did not elaborate on the importance of cultural expectations, family dynamics, and physician-interactions in the determination for or against bracing. Both, the Sponseller review2 and the Weinstein review1 recommended a shared decision-making model to be used. The effects of a shared decision-making model in regards to patient outcomes and conversion rates to surgery of patients presenting with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis remain unknown. In terms of study size and long-term dimensions the reviewers recommend reading the Nachemson study from 1995, which was part of the systematic review performed here.3

References

- 1.Negrini S, Minozzi S, Bettany-Saltikov J. et al. Braces for idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;2:1285–1293. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181dc48f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weiss H R, Goodall D. The treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) according to present evidence: a systematic review. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2008;2(2):177–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenssinck M L, Frijlink A C, Berger M Y. et al. Effect of bracing and other conservative interventions in the treatment of idiopathic scoliosis in adolescents: a systematic review of clinical trials. Phys Ther. 2005;2(2):1329–1339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowe D E, Bernstein S M, Riddick M F. et al. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of non-operative treatments for idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;2(2):664–674. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199705000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nachemson A L, Peterson L E. Effectiveness of treatment with a brace in girls who have adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a prospective, controlled study based on data from the Brace Study of the Scoliosis Research Society. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;2(2):815–822. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199506000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danielsson A J, Hasserius R, Ohlin A. et al. A prospective study of brace treatment versus observation alone in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a follow-up mean of 16 years after maturity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;2:2198–2207. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31814b851f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez-Feliberti R, Flynn J, Ramirez N. et al. Effectiveness of TLSO bracing in the conservative treatment of idiopathic scoliosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;2:176–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung K M, Cheng E Y, Chan S C. et al. Outcome assessment of bracing in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis by the use of the SRS-22 questionnaire. Int Orthop. 2007;2(2):507–511. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0209-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parent E C, Hill D, Mahood J. et al. Discriminative and predictive validity of the scoliosis research society-22 questionnaire in management and curve-severity subgroups of adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009;2:2450–2457. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181af28bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mannherz R E, Betz R R, Clancy M. et al. Juvenile idiopathic scoliosis followed to skeletal maturity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1988;2:1087–1090. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pham V M, Houlliez A, Carpentier A. et al. Determination of the influence of the Cheneau brace on quality of life for adolescent with idiopathic scoliosis. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2008;2(2):3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annrmp.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ugwonali O F, Lomas G, Choe J C. et al. Effect of bracing on the quality of life of adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis. Spine J. 2004;2(2):254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Editorial Perspective

- 1.Weinstein S L, Dolan L A, Cheng J C. et al. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Seminar. Lancet. 2008;2(2):1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60658-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sponseller P D. Bracing for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in practice today. J Pediatr Orthop. 2011;2 01:S53–S60. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181f73e87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nachemson A, Peterson L E. Effectiveness of treatment with a brace in girls who have adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a prospective, controlled study based on data from the brace study of the Scoliosis Research Society. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;2:815–822. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199506000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]