Abstract

Substance use is prevalent among HIV-positive adults and linked to a number of adverse health consequences; however little is known about risk and protective factors that influence substance use among HIV-positive adults coping with AIDS-related bereavement. Using structural equation modeling (SEM), male gender, diagnostic indications of antisocial and borderline personality disorders (PD), and grief severity were tested as risk factors, and social support as a protective factor, for alcohol and cocaine use among a diverse sample of 268 HIV-positive adults enrolled in an intervention for AIDS-related bereavement. Results indicated that the hypothesized model fit the study data. Male gender, PD indication, and social support had direct effects on substance use. PD had significant indirect effects on both alcohol and cocaine use, mediated by social support, but not by grief. Finally, both PD and social support had significant, but opposite, effects on grief. Implications for intervention and prevention efforts are discussed.

Keywords: Bereavement, Complicated grief, Personality disorder, Social support, Substance use

Despite advances in treatment for HIV infection, more than half a million people have died from AIDS in the U.S., including between 15,798 and 17,849 annually between 2000 and 2004 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2005), and AIDS-related bereavement is an experience shared by many. While many people adapt to bereavement over time, for some grieving remains unresolved, or complicated (Zhang et al. 2006). Complicated grief has been proposed as a distinct clinical syndrome characterized by a chronic state of mourning that impairs the survivor's psychosocial functioning. Risk factors for complicated grief include “excessive stresses concurrent with the death” (Mallinson 1999, p. 166), deaths from overly-lengthy illness, and perceived lack of social support (Rando 1992). AIDS-bereaved survivors who are HIV-positive are particularly susceptible to complicated grief as they: (a) must simultaneously cope with the loss of a loved one while being reminded of their own mortality through a loss to the same illness that is threatening their own lives (Sherr et al. 1992); (b) are often members of disenfranchised communities and thereby receive less sympathy and support from the public; (c) may have reduced social support due to AIDS-related losses within their own communities; (d) may have been involved in a care-taking role with the lost loved one; and (e) are often coping with multiple losses (Mallinson 1999). In non-HIV infected samples, AIDS-related bereavement (Martin 1988) and complicated grief (Prigerson et al. 1997) have been linked to increased substance use and abuse; however, to our knowledge, no studies have examined the impact of grief on the substance use behaviors of HIV-infected adults coping with AIDS-related bereavement.

Substance use and abuse are prevalent among persons with HIV/AIDS and are associated with deleterious health outcomes, including death (Bing et al. 2001; Chander et al. 2006; Galvan et al. 2002). In fact, although antiretroviral drugs have lengthened the lives of many with HIV/AIDS, medical professionals are now seeing an increase in non-HIV related deaths among those with HIV, with 31% of those deaths being attributed to substance use (Sackoff et al. 2006). In a population sample of persons with HIV/AIDS, over half reported alcohol use in the previous 4 weeks and nearly 20% reported “heavy” or “frequent heavy” use of alcohol (Bing et al. 2001; Galvan et al. 2002). Galvan and colleagues (2002) also found that 16.9% had used cocaine or heroin, and Bing and colleagues (2001) found that half had used an illicit drug in the last 12 months. Additionally, cocaine and alcohol use have been associated with nonadherence to antiretroviral and mental health treatment (Cook et al. 2001; Tucker et al. 2003). Given the prevalence of substance use and associated problems among HIV-positive adults, there is a need to know more about the risk and protective factors for substance use behavior in this population in order to reduce substance use and abuse and improve health outcomes.

Persons living with HIV/AIDS are also more likely to suffer from personality disorders (PD), particularly antisocial PD and borderline PD (Golding and Perkins 1996; Taylor et al. 1996). Although there is a paucity of research pertaining to PD among HIV-infected persons (Singh and Ochitill 2006), research in the general population and broader clinical populations documents an association between antisocial PD and borderline PD and substance use disorders (Compton et al. 2005; Feske et al. 2006). Further, patients with borderline and antisocial traits are difficult to engage in treatment, are frequently non-adherent, and continue to engage in HIV risk behaviors (Palmer et al. 2003; Singh and Ochitill 2006).

Among persons grieving the loss of a loved one, alcohol use and a history of mental illness have been viewed as risks for developing complicated bereavement (Ellifritt et al. 2003). Additionally, people with PD frequently experience unstable and tumultuous interpersonal relationships, maladaptive coping styles, and engage in self-harm and high-risk behavior (American Psychiatric Association 1994). The process of bereavement may exacerbate and highlight these maladaptive ways of coping. One outlet for coping with negative emotion and loss is through the use of substances. The use of substances to cope with an AIDS-related loss among those living with HIV/AIDS and PD is particularly concerning given the negative consequences of substance use on health in people living with HIV infection (Neuman et al. 2006; Sackoff et al. 2006).

Social support has been identified as a protective factor for life stressors (Cohen and Wills 1985) and linked with decreased distress in HIV-positive adults (Hays et al. 1992), particularly during later stages of disease progression (Balbin et al. 1999; Miller and Cole 1998). Recent evidence suggests a positive association between social support and the use of antiretroviral treatment, although the relationship appears to be contingent upon disclosure of HIV status (Waddell and Messeri 2006). In addition, social support has been linked with more use of active coping strategies and less use of avoidant and self-destructive coping strategies (Tarakeshwar et al. 2005). In turn, low levels of social support have been linked to grief and suicidal ideation in bereaved samples (Rosengard and Folkman 1997), including complicated grief reactions (Ott 2003); a greater use of self-destructive coping, including drinking more than usual, among HIV-positive gay and bisexual men (Tate et al. 2006); and more distress in HIV-positive women (Hudson et al. 2001).

Given the negative health consequences of substance abuse in people living with HIV, and the potential for grief to exacerbate substance use, particularly in those with PD characteristics, the present study examined the relationships between these variables in a sample of persons with HIV/AIDS who have experienced an AIDS-related loss. Specifically, this study investigated a structural model of the relationships between antisocial PD and borderline PD characteristics, participant gender, and alcohol and cocaine use. Additionally, the potential mediating effects of social support and grief were examined in the model. The study hypothesized that social support would have a direct negative effect on substance use; grief would have a direct positive effect on substance use; PD characteristics would be directly related to substance use, and indirectly related to substance use through both social support and grief; and participant gender would be directly related to substance use, with men reporting more use than women, and that gender would be indirectly related to substance use through both social support and grief. To test these hypotheses, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test the significance of the hypothesized relationships between variables, as well as the overall fit of the hypothesized model to the actual data.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

A total of 268 HIV-positive participants (94 women, 174 men) were recruited in Milwaukee, WI, and New York, NY to take part in a randomized, controlled trial of a group intervention for coping with AIDS-related bereavement (Hansen et al. 2006, 2007; Sikkema et al. 2006). Participants were recruited through HIV service organizations and medical and mental health care providers between June 1997 and April 1999. HIV-positive individuals who had lost a partner/lover, spouse, family member, or close friend to AIDS were included according to the following eligibility criteria: (a) health care provider verification of HIV-positive serostatus; (b) experience of an AIDS-related loss not less than 1 month and not more than 2 years ago; (c) not currently psychotic, as measured at screening by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Screen Patient Questionnaire (SCID Screen PQ; First et al. 1996); and (d) no more than mild cognitive impairment as measured by the Mini Mental Status Exam (MMSE; Folstein et al. 1975). Of the 322 persons initially screened, 54 people began the screening process but did not enter the study (38 dropped out voluntarily, 15 were ineligible to participate, and 1 died). Those who did not participate differed from participants on two variables: they were more likely than participants to be heterosexual (χ2 = 6.9, P<.01) and had fewer sex partners who died of AIDS (Mann–Whitney U, z = −2.05, P<.05).

Measures

Participant Gender

A dichotomous variable of participant gender was created. Three transsexual participants were coded based on their self-identification: two male and one female.

Personality Disorder Indication

The Computer-Assisted SCID-II (CAS-II) program was used to screen for PD (First et al. 1997). As participants in this study were part of a group intervention RCT, only the screening questions for antisocial PD and borderline PD were included, as these disorders may present the most complications for group treatment. While the authors of CAS-II do not recommend using this instrument to establish a diagnosis (First et al. 1997), a number of studies indicate that the CAS-II is a useful measure on its own. For example, the CAS-II has been shown to correlate with other measures of personality and symptoms (Piedmont et al. 2003), have a low false negative rate (Jacobsberg et al. 1995), have high stability over time (Ouimette and Klein 1995), and have high sensitivity and utility as an epidemiological tool to estimate rates of PD within a population (Ekselius et al. 1994). As no significant differences were found between participants with antisocial PD indication and borderline PD indication on study variables, and only 16 participants received an antisocial PD indication, antisocial PD and borderline PD were combined into a single dichotomous variable representing the presence or absence of a PD indication. This same procedure has also been used in a study predicting HIV symptoms and health-related quality of life (Hansen et al. 2007).

Social Support

A latent variable representing the construct of social support was created using the four 10-item subscales of the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL; Cohen et al. 1985). These subscales include: (1) Tangible Support, which reflects the availability of material aid; (2) Appraisal Support, which measures the availability of others with whom one can discuss issues of personal importance; (3) Self-Esteem Support, which measures the presence of others who potentially bolsters one's sense of self-worth; and (4) Belonging Support, which reflects the presence of others with whom one can identify and socialize. Participants responded to each ISEL item on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = definitely true to 4 = definitely false); items were coded such that higher scores were indicative of greater perceived social support. The ISEL has demonstrated adequate criterion validity, test-retest reliability, and internal consistency (Cohen et al. 1985). For the current sample, internal consistency was good (Tangible Support, α = .84; Appraisal Support, α = .83; Self-Esteem Support, α = .74; Belonging Support, α = .83).

Grief Severity

A latent variable representing grief severity was created using the Grief Reaction Index (GRI) (Lennon et al. 1990) and the two subscales of the Impact of Events Scale (IES) (Horowitz et al. 1979). The 12-item GRI measures common grief symptoms of numbness, denial, and preoccupation with the deceased. Participant responded using a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never to 4 = very often) which were summed to yield an overall grief score such that higher scores indicated more grief (Cronbach's α = .87, current sample). The 15-item IES measures stress associated with traumatic events. It consists of two subscales, one (7 items) reflecting intrusive stress experiences such as stress-related thoughts, feelings, or bad dreams; and the other (8 items) reflecting avoidance of ideas, feelings, and situations associated with a traumatic stressor. Participants completed the IES with the loss of a loved one to AIDS as the referent stressor. Items use a 4-point Likert scale to rate how frequently the intrusive or avoidance reaction occurred, with higher scores reflecting more stressful impact. The IES has been widely used across numerous studies and has well established psychometric properties (Sundin and Horowitz 2003). The internal consistency of the IES was good in the current sample (Intrusion, Cronbach's α = .89; Avoidance, Cronbach's α = .89).

Substance Use Variables

The substance abuse scale assessed the frequency of use of a number of substances, including alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, tranquilizers, narcotics, amphetamines, and injection drugs (Sikkema et al. 2003). Participants rated their use of each substance over the previous 4 months on a six point Likert scale (0 = No use, 1 = Once or twice a month, 2 = About once a week, 3 = Several times a week, 4 = About every day, and 5 = More than once a day). For the current analyses, categories 4 and 5 were collapsed into a single category reflecting daily use or more. Additionally, only data on alcohol and cocaine were utilized, as reported use of other substances was infrequent.

Statistical Analysis

Structural equation modeling was used to assess the hypothesized model, including: (1) the overall fit of the model, (2) the amount of variability (R2) of the latent mediating variables and outcome variables accounted for by the predictive variables in the model, and (3) the significance of the direct and indirect structural paths between predictor variables and outcome variables. The goodness-of-fit χ2, the RMSEA, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) were used to evaluate the overall fit of the model. A non-significant goodness-of-fit χ2 value indicates that the hypothesized model does not differ significantly from the actual covariance structure of the data. Additionally, RMSEA values under 0.06 and CFI and TLI values greater than .95 indicate relatively good fit (Hu and Bentler 1999).

Ordinal categorical or nominal data violate assumptions of SEM using maximum likelihood (ML) estimation, resulting in inefficient estimates and increased type I error rates (Nussbeck et al. 2006). While methods such as weighted least squares (WLS) have been developed for modeling ordinal data, they require large sample sizes. As an alternative, the robust WLS mean- and variance-adjusted χ2 test (WLSMV) was developed and shown to have good statistical properties in testing model fit with relatively small sample sizes (N = 200) and ordinal outcomes (Nussbeck et al. 2006). As the current study uses both dichotomous indicator variables and ordinal categorical outcome variables, the evaluation of the hypothesized structural model was conducted using WLSMV, available with the computer program Mplus.

Results

Demographic and Loss Characteristics

Participants were predominately ethnic minorities (72.8%) and impoverished, with 90.9% reporting annual incomes under $20,000. Most had completed high school or equivalent (75.7%), with 39.0% reporting some college education. Participants reported wide variability in disease progression. On average, participants had been living with HIV for 7 years (range from 2 months to 16 years), and while 35.7% report experiencing no symptoms of HIV, 45.8% reported having previously been diagnosed with AIDS. Supporting the argument that HIV disrupts, and can devastate, social support networks, participants reported tremendous numbers of HIV-related losses. As a number of men reported well over 100 AIDS-related losses, data was winsorized (a method for correcting for outliers without removing data by setting tail values of the distribution equal to a specified percentile of the data), and outliers over the 95th percentile (102 AIDS-related deaths) were recoded as having experienced 103 AIDS-related deaths, resulting in a mean of 16 deaths of loved ones to AIDS (median = 7). One participant in five (19.4%) had lost over 20 loved ones to AIDS, while only 8.6% reported one AIDS-related loss. Table 1 presents comparisons of demographic and loss info by gender.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of sample by gender

| Men (N = 174) |

Women (N = 94) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N (%) | N (%) | χ 2 |

| Categorical | |||

| Ethnicity | 9.52 | ||

| African-American | 91 (52.3%) | 54 (57.4%) | |

| White/Caucasian | 57 (32.8%) | 16 (17.0%) | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 12 (6.9%) | 11 (11.7%) | |

| Other or Mixed | 14 (8.0%) | 13 (13.8%) | |

| Sexual orientation | 124.72** | ||

| Heterosexual | 38 (21.8%) | 86 (91.5%) | |

| Gay/Bisexual | 136 (78.2%) | 8 (8.5%) | |

| Ever diagnosed with AIDS | 79 (45.4%) | 41 (43.6%) | 0.17 |

| Partner/Spouse died from AIDS | 81 (46.6%) | 43 (45.7%) | 0.02 |

| Caregiver for lost loved one | 153 (87.9%) | 75 (79.8%) | 3.19 |

| Variables | M (s.d.) | M (s.d.) | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous | |||

| Participant age in years | 40.0 (7.3) | 40.3 (6.4) | −.27 |

| Years of education | 13.1 (2.2) | 12.0 (2.2) | 3.94** |

| Years since HIV diagnosis | 7.4 (4.1) | 6.1 (3.8) | 2.36* |

| Number of AIDS-related loses | 9a | 5a | −3.59**b |

Value significant, P < .05;

Value significant, P < .01

Number represents the median within each gender

Mann–Whitney U z-score

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents descriptive information for study variables by gender. Most participants (69.8%) reported a history of substance abuse, and half (52.8%) reported receiving treatment for substance abuse at some point in their lives. Over the previous 4 months, 45.9% of participants reported alcohol use and 18.3% reported cocaine use. Participant responses on the CAS-II indicated that 28.4% of participants had indications of a PD. Although overall rates of PD indication (antisocial PD and borderline PD combined in a single variable) did not differ by gender (χ2 = .90, P = .34), it can be seen in Table 2 that rates of antisocial PD and borderline PD did differ by gender when considered independently.

Table 2.

Descriptive data for independent and dependent variables compared by gender

| Men (N = 174) |

Women (N = 94) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N (%) | N (%) | χ 2 |

| Categorical | |||

| Alcohol use | 28.11** | ||

| No use | 75 (43.1%) | 70 (74.5%) | |

| Monthly | 31 (17.8%) | 13 (13.8%) | |

| Weekly | 29 (16.7%) | 7 (7.4%) | |

| Several times a week | 27 (15.5%) | 3 (3.2%) | |

| Daily | 12 (6.9%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Cocaine use | 2.28 | ||

| No use | 140 (80.5%) | 79 (84%) | |

| Monthly | 17 (9.8%) | 5 (5.3%) | |

| Weekly | 3 (1.7%) | 3 (3.2%) | |

| Several times a week | 9 (5.2%) | 4 (4.3%) | |

| Daily | 5 (2.9%) | 3 (3.2%) | |

| Axis 2 indicated | 7.38* | ||

| Antisocial personality traits | 14 (8.0%) | 2 (2.1%) | |

| Borderline personality traits | 32 (18.4%) | 28 (29.8%) |

| Variables | M (s.d.) | M (s.d.) | t |

|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous | |||

| Social support | |||

| ISEL Appraisal subscale | 20.26 (6.33) | 20.01 (5.85) | 0.31 |

| ISEL Self-Esteem subscale | 18.72 (4.84) | 17.98 (5.08) | 1.18 |

| ISEL Tangible subscale | 19.81 (6.52) | 18.73 (6.52) | 1.29 |

| ISEL Belonging subscale | 20.43 (5.78) | 20.31 (6.08) | 0.16 |

| Grief severity | |||

| Grief reaction inventory | 18.59 (9.42) | 20.55 (10.85) | 1.53 |

| IES Intrusion subscale | 14.65 (9.19) | 15.46 (9.93) | 0.67 |

| IES Avoidance subscale | 14.46 (10.03) | 17.56 (11.90) | 2.25* |

Value significant, P < .05;

Value significant, P < .01

Model Predicting Alcohol and Cocaine Use

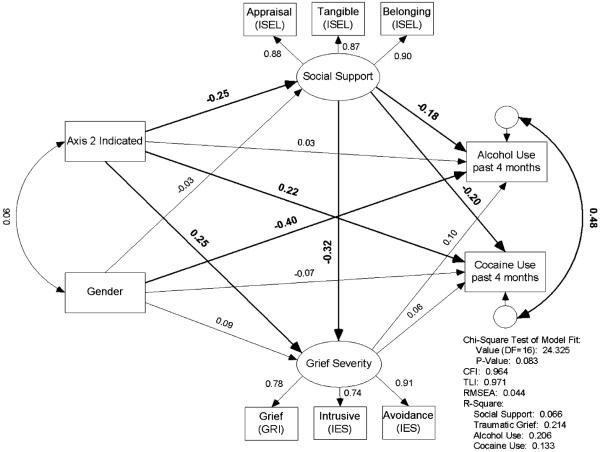

The fit of the hypothesized structural model was tested in a three-step process. First, a confirmatory analysis evaluated the measurement model of the two latent constructs (social support and grief severity) without any structural paths (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). The measurement model demonstrated reasonable fit (χ2 (13) = 28.67, P = .007; CFI = .99; TLI = .98; RMSEA = .07). Second, manifest variables and hypothesized structural paths were added to the model. Similar to the measurement model, this model showed reasonable fit (χ2 (19) = 37.28, P = .007; CFI = .94; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .06). Third, an examination of variable correlations (shown in Table 3) and loadings within the structural model suggested that the self-esteem subscale of the ISEL was detracting from model fit. Thus, a final model was evaluated without the ISEL self-esteem subscale loading on the social support latent construct. This model, shown in Fig. 1, achieved good fit with a non-significant χ2 (χ2 (16) = 24.33, P = .08), both CFI and TLI above .95 (CFI = .96; TLI = .97), and RMSEA below .06 (RMSEA = .04). Figure 1 also presents R2 values for each latent variable and outcome variable, indicating the amount of variance within each construct or outcome variable accounted for by the predictor variables in the structural model. Table 4 presents all of the coefficients of the direct paths and summed coefficients of indirect paths modeled in Fig. 1.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix of variables used in the structural equation model

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | – | ||||||||||

| 2. Alcohol use | − .299 | – | |||||||||

| 3. Cocaine use | −.037 | .336 | – | ||||||||

| 4. Axis 2 indicated | .058 | .070 | .203 | – | |||||||

| 5. ISEL Appraisal support | −.029 | − .159 | − .219 | − .250 | – | ||||||

| 6. ISEL Self-Esteem support | −.059 | −.069 | − .138 | − .324 | .599 | – | |||||

| 7. ISEL Tangible support | −.090 | −.085 | − .156 | − .206 | .729 | .602 | – | ||||

| 8. ISEL Belonging support | −.011 | − .166 | − .149 | − .233 | .807 | .723 | .806 | – | |||

| 9. GRI | .090 | .095 | .111 | .238 | − .266 | − .293 | − .295 | − .259 | – | ||

| 10. IES Intrusion | .039 | .090 | .109 | .223 | − .215 | − .243 | − .221 | − .206 | .629 | – | |

| 11. IES Avoidance | .125 | .036 | .105 | .316 | − .346 | − .369 | − .335 | − .320 | .636 | .725 | – |

Note: Bold numbers indicate statistical significance (P < .05). ISEL = Interpersonal Support Evaluation List; GRI = Grief Reaction Index; IES = Impact of Events Scale

Fig. 1.

Structural equation model predicting alcohol and cocaine use in a sample of HIV-positive adults who have experienced an AIDS-related loss

Table 4.

Indirect effects of predictor variables on alcohol and cocaine use

| Social support | Grief severity |

Alcohol use |

Cocaine use |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Direct | Indirect | Direct | Indirect | Direct | Indirect | |

| Axis II Indicated | −.25** | .25** | .08** | .03 | .08** | .22* | .07* |

| Gender | −.03 | .09 | .01 | −.40** | .01 | −.07 | .01 |

| Social Support | −.32** | −.18** | −.03 | −.20* | −.02 | ||

| Grief Severity | .10 | .06 | |||||

Value significant, P < .05;

Value significant, P < .01

Alternative models were also tested, including a model with antisocial PD and borderline PD indications entered independently rather than as a combined variable, and a model including sexual orientation of participants. These models did not achieve acceptable fit, and therefore are not reported here, though patterns of relationships were consistent with the model shown in Fig. 1. Of note, however, borderline PD, but not antisocial PD, was significantly related to grief severity when these were modeled as independent variables (though antisocial PD did trend toward significance); and though both heterosexual men and MSM were more likely to use alcohol than women, MSM were more likely than heterosexual men to use alcohol.

Discussion

The current study tested male gender, PD indications, and grief severity as risk factors, and social support as a protective factor, for substance use in a high-risk sample of HIV-positive adults who have lost loved-ones to AIDS. As hypothesized, antisocial PD or borderline PD indication had a direct effect on cocaine use, though contrary to hypotheses, there was not a direct effect of PD indication on alcohol use. Additionally, PD indication had significant indirect effects on both alcohol use and cocaine use, with this relationship mediated by social support, but not grief. Specifically, individuals with indications of PD were less likely to experience social support, and in turn, were more likely to use alcohol and cocaine. The hypothesized path through grief severity was not significant. In fact, in the current analysis, level of grief did not have any relationship with substance use. Given the frequency of substance abuse problems in people living with HIV (Bing et al. 2001), and that substance use often precedes HIV infection, it is probable that the use of drugs and alcohol by some HIV-positive participants in the current sample represents substance use problems relatively independent of bereavement or grief severity. Additionally, people living with HIV have numerous stressors associated with their disease and social status, thus participants in this study likely have multiple potential triggers for substance use, likely resulting in greater difficulty determining the unique impact of bereavement on substance use for these participants than in less stressed populations. Additionally, our hypotheses around gender were not supported as, with the exception of male gender predicting alcohol use, there were no significant direct or indirect effects of gender on study variables. Finally, both PD indication and social support had significant, though opposite, effects on grief severity (with PD indication linked to increases in, and social support linked to decreases in, grief severity); and antisocial PD and borderline PD indications had significant indirect effects on grief through reduced perception of social support.

The influence of social support within the structural model is important to note. All direct paths from social support were significant, and social support mediated all significant indirect paths in the model. Higher social support appears to be a protective factor against grief, and is related to lower levels of substance use in this sample. It is possible that the influence of social support is particularly strong within this population, which is characterized by many stigmatizing features, including HIV infection, racial/ethnic minority status, substance use, and homosexuality. Participant responses on the ISEL represent relatively low levels of social support when compared to reported responses from other studies with chronic or life threatening illnesses. For example, participants in the current sample had significantly lower ISEL scores than patients with end-stage renal disease (Symister and Friend 2003) and metastatic breast cancer (Turner-Cobb et al. 2000). The low reported levels of social support in this sample are not surprising, however, given the potential disruptions to social support networks created by the numerous losses these participants have experienced.

There are a number of limitations to this research that should be noted. For instance, the PD indication variable does not represent a formal DSM-IV diagnosis, and while the CAS-II is likely to provide reliable estimates of the prevalence of PD in a population (Ekselius et al. 1994), the reliability of such an indication for each individual is unknown. The substance use variables used in this study represent the frequency of use over the previous 4 months, and are not adequate to determine total level (amount) of use, or the impact of substance use on functioning, such that an indication of substance abuse could be determined. Additionally, all of the variables used in the structural model are based on participant self-report, thus variables such as PD indication and level of substance abuse may be underreported; and the data in this study are cross-sectional, limiting the ability to draw conclusions regarding the direction of relationships.

The construct of grief is based on scores from the GRI and IES, both rated in relation to the loss of a loved one to AIDS. Although neither of these instruments was developed to specifically measure complicated grief, there is evidence that similar measures are useful for assessing complicated grief reactions (Boelen and van den Bout 2005), and the IES has been used to measure intrusive and avoidant symptoms related to the experience of bereavement and loss (Sundin and Horowitz 2003). Also, participants are seeking services (i.e., they are enrolling in a group intervention to address their bereavement related to AIDS-related loss) and share the same diagnosis as the lost loved one, indicated that they are at elevated risk for complicated grief.

The current study utilized one of the largest data sets in the HIV bereavement literature, and represents a very diverse range of participants, including women, gay and bisexual men, and heterosexual men from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. Additionally, data were drawn from two distinct and diverse geographical locations within the United States, New York City, which is an HIV/AIDS epicenter with comparatively extensive services and support for people living with HIV, and Milwaukee, WI, a smaller Midwestern city with comparatively fewer resources for people living with HIV infection. Given the composition of the sample, the ability of the current findings to be generalized across other HIV-positive, bereaved samples in the United States is strengthened. Further, while it is likely that variables such as grief and social support may manifest differently in different subsamples (e.g., women, MSM, heterosexual men), our data suggests that the relationship between these variables will remain similar.

Despite the prevalence, and associated complications, of PD among the HIV infected, the literature on comorbid PD and HIV infection is relatively sparse. What is most frequently noted is that these individuals are more likely to: (a) engage in substance abuse, (b) engage in ongoing HIV risk behavior that may increase the risk of transmission to others, (c) have disrupted relationships and impaired social support, (d) be less responsive to HIV prevention messages, and (e) have poorer treatment adherence (Singh and Ochitill 2006). Thus individuals with PD have a great need for effective interventions. Yet, these individuals are difficult to engage in interventions and less likely to adequately utilize them. It is not surprising that the number of empirically supported treatment options for PD are limited, and to date, we are aware of only one intervention, Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), that has been modified to address PD in the context of HIV infection (Wagner et al. 2004), though empirical support for this modified intervention has yet to be established. Clearly much more research is needed on the negative health consequences that accompany PD in people living with HIV, including poorer treatment adherence, maladaptive coping strategies, substance abuse, and diminished quality of life. For example, our data have shown that PD indications are predictive of increased HIV symptoms and decreased health-related quality of life (Hansen et al. 2007). Additionally, empirically-supported substance use prevention and HIV risk-reduction interventions, and mental health treatments, are needed to address the complex needs of individuals with comorbid PD and HIV infection.

With advances in treatment that have significantly decreased the number of deaths directly attributable to AIDS, people living with HIV infection are living long enough to die from alternative causes, many of which are directly (Sackoff et al. 2006) and indirectly (Bica et al. 2001) related to substance use and abuse. Additionally, there is evidence that alcohol use has a synergistic effect with antiretroviral therapies, resulting in increased hepatotoxicity (Neuman et al. 2006), and contributing to accelerated disease progression in comorbid conditions such as Hepatitis C (Cooper and Cameron 2005). It is important, therefore, to identify risk factors for increased substance use, and to develop effective prevention and treatment strategies to reduce substance use, among people living with HIV infection (Bryant 2006).

HIV-positive individuals are at increased risk for experiencing stressful and traumatic events, including AIDS-related losses, and these experiences increase the risk of substance use and abuse. We found social support to provide a buffer against substance use, which suggests that enhancing and mobilizing social support resources may be an effective strategy for prevention and treatment with this population, and supports the use of group intervention formats in addressing grief and substance use (see Hansen et al. 2006; Sikkema et al. 2006). It is important, therefore, that integrated HIV/AIDS services be established that can provide: (a) adequate case management and links to care providers; (b) links and access to available social support resources, including support and self-help groups and community and/or religious organizations; and (c) coping skills training to enhance the ability of HIV-positive individuals to cope effectively with stressors.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants R01-MH54958, K23-MH076671, and P30-MH62294 (Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS), from the National Institute of Mental Health; and T32-DA019426, from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The authors gratefully acknowledge our community collaborations with the AIDS Resources Center for Wisconsin, the Madison AIDS Support Network, and the Callen-Lorde Community Health Center in New York City.

References

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed Author; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JC, Gerbing DW. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin. 1988;103:411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Balbin EG, Ironson GH, Solomon GF. Stress and coping: The psychoneuroimmunology of HIV/AIDS. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1999;13:615–633. doi: 10.1053/beem.1999.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bica I, McGovern B, Dhar R, Stone D, McGowan K, Scheib R, et al. Increasing mortality due to end-stage liver disease in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;32:492–497. doi: 10.1086/318501. see comment. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, Fleishman JA, Sherbourne CD, London AS, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:721–728. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boelen PA, van den Bout J. Complicated grief, depression, and anxiety as distinct postloss syndromes: A confirmatory factor analysis study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:2175–2177. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant KJ. Expanding research on the role of alcohol consumption and related risks in the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS. Substance Use & Misuse. 2006;41:1465–1507. doi: 10.1080/10826080600846250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 2004. 2005 from Retrieved February 14, 2007 from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/stats/hasrlink.htm.

- Chander G, Himelhoch S, Moore RD. Substance abuse and psychiatric disorders in HIV-positive patients: Epidemiology and impact on antiretroviral therapy. Drugs. 2006;66:769–789. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman HM. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason BR, Sarason IG, editors. Social support: Theory, research, and applications. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; Boston, MA: 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Conway KP, Stinson FS, Colliver JD, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity of DSM-IV antisocial personality syndromes and alcohol and specific drug use disorders in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005;66:677–685. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RL, Sereika SM, Hunt SC, Woodward WC, Erlen JA, Conigliaro J. Problem drinking and medication adherence among persons with HIV infection. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:83–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.00122.x. see comment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CL, Cameron DW. Effect of alcohol use and highly active antiretroviral therapy on plasma levels of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in patients coinfected with HIV and HCV. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005;41(Suppl 1):S105–109. doi: 10.1086/429506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekselius L, Lindstrom E, von Knorring L, Bodlund O, Kullgren G. SCID II interviews and the SCID Screen questionnaire as diagnostic tools for personality disorders in DSM-III-R. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1994;90:120–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellifritt J, Nelson KA, Walsh D. Complicated bereavement: A national survey of potential risk factors. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care. 2003;20:114–120. doi: 10.1177/104990910302000209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske U, Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Pilkonis PA. Borderline personality and substance use in women. American Journal on Addictions. 2006;15:131–137. doi: 10.1080/10550490500528357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. Users guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV disorders. research version (SCID-I, Version 2.0) 1996. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Benjamin LS. Users guide for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan FH, Bing EG, Fleishman JA, London AS, Caetano R, Burnam MA, et al. The prevalence of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking among people with HIV in the United States: Results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63:179–186. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding M, Perkins DO. Personality disorder in HIV infection. International Review of Psychiatry. 1996;8(2–3):253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen NB, Tarakeshwar N, Ghebremichael M, Zhang H, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Longitudinal effects of coping on outcome in a randomized controlled trial of a group intervention for HIV-positive adults with AIDS-related bereavement. Death Studies. 2006;30:609–636. doi: 10.1080/07481180600776002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen NB, Vaughn EL, Cavanaugh CE, Connell CM, Sikkema KJ. Health-related quality of life in bereaved HIV-positive adults: Relationships between HIV symptoms, grief, social support, and Axis II indication. Manuscript Submitted for Review. 2007 doi: 10.1037/a0013168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays RB, Turner H, Coates TJ. Social support, AIDS-related symptoms, and depression among gay men. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:463–469. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of event scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L.-t., Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson AL, Lee KA, Miramontes H, Portillo CJ. Social interactions, perceived support, and level of distress in HIV-positive women. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2001;12:68–76. doi: 10.1016/S1055-3290(06)60218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsberg L, Perry S, Frances A. Diagnostic agreement between the SCID-II screening questionnaire and the Personality Disorder Examination. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1995;65:428–433. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon MC, Martin JL, Dean L. The influence of social support on AIDS-related grief reaction among gay men. Social Science & Medicine. 1990;31:477–484. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(90)90043-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallinson RK. Grief work of HIV-positive persons and their survivors. Nursing Clinics of North America. 1999;34:163–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JL. Psychological consequences of AIDS-related bereavement among gay men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(6):856–862. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Cole SW. Social relationships and the progression of human immunodeficiency virus infection: A review of evidence and possible underlying mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;20:181–189. doi: 10.1007/BF02884959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman MG, Monteiro M, Rehm J. Drug interactions between psychoactive substances and antiretroviral therapy in individuals infected with human immunodeficiency and hepatitis viruses. Substance Use & Misuse. 2006;41:1395–1463. doi: 10.1080/10826080600846235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbeck FW, Eid M, Lischetzke T. Analysing multitrait-multimethod data with structural equation models for ordinal variables applying the WLSMV estimator: What sample size is needed for valid results? British Journal of Mathematical & Statistical Psychology. 2006;59:195–213. doi: 10.1348/000711005X67490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott CH. The impact of complicated grief on mental and physical health at various points in the bereavement process. Death Studies. 2003;27:249–272. doi: 10.1080/07481180302887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette PC, Klein DN. Testetest stability, mood-state dependence, and informant subject concordance of the SCID-Axis II Questionnaire in a nonclinical sample. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1995;9:105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer NB, Salcedo J, Miller AL, Winiarski M, Arno P. Psychiatric and social barriers to HIV medication adherence in a triply diagnosed methadone population. AIDS Patient Care & Stds. 2003;17:635–644. doi: 10.1089/108729103771928690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piedmont RL, Sherman MF, Sherman NC, Williams JE. A first look at the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV personality disorders screening questionnaire: More than just a screener? Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development. 2003;36:150–160. [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson HG, Bierhals AJ, Kasl SV, Reynolds CF, III, Shear MK, Day N, et al. Traumatic grief as a risk factor for mental and physical morbidity. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:616–623. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.5.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rando TA. The increasing prevalence of complicated mourning: The onslaught is just beginning. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying. 1992;26:43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rosengard C, Folkman S. Suicidal ideation, bereavement, HIV serostatus and psychosocial variables in partners of men with AIDS. AIDS Care. 1997;9:373–384. doi: 10.1080/713613168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackoff JE, Hanna DB, Pfeiffer MR, Torian LV. Causes of death among persons with AIDS in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: New York City. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145:397–406. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-6-200609190-00003. [see comment][summary for patients in Ann Intern Med. 2006 Sep 19;145(6):I49; PMID: 16983125] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr L, Hedge B, Steinhart K, Davey T, Petrack J. Unique patterns of bereavement in HIV: Implications for counselling. Genitourinary Medicine. 1992;68:378–381. doi: 10.1136/sti.68.6.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Ghebremichael M, Kochman A, Tarakeshwar N, Meade CS, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a coping group intervention for adults with HIV who are AIDS bereaved: Longitudinal effects on grief. Health Psychology. 2006;25:563–570. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikkema KJ, Kochman A, DiFranceisco W, Kelly JA, Hoffmann RG. AIDS-related grief and coping with loss among HIV-positive men and women. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26:165–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1023086723137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh K, Ochitill H. Personality disorders. In: Fernandez F, Ruiz P, editors. Psychiatric aspects of HIV/AIDS. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2006. pp. 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Sundin EC, Horowitz MJ. Horowitz's Impact of Event Scale evaluation of 20 years of use. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2003;65:870–876. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000084835.46074.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symister P, Friend R. The influence of social support and problematic support on optimism and depression in chronic illness: A prospective study evaluating self-esteem as a mediator. Health Psychology. 2003;22:123–129. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.22.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarakeshwar N, Hansen N, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Gender, ethnicity and spiritual coping among bereaved HIV-positive individuals. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2005;8:109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Tate DC, Van Den Berg JJ, Hansen NB, Kochman A, Sikkema KJ. Race, social support, and coping strategies among HIV-positive gay and bisexual men. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2006;8:235–249. doi: 10.1080/13691050600761268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor ER, Amodei N, Mangos R. The presence of psychiatric disorders in HIV-infected women. Journal of Counseling & Development. 1996;74:345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Burnam MA, Sherbourne CD, Kung FY, Gifford AL. Substance use and mental health correlates of nonadherence to antiretroviral medications in a sample of patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. American Journal of Medicine. 2003;114:573–580. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner-Cobb JM, Sephton SE, Koopman C, Blake-Mortimer J, Spiegel D. Social support and salivary cortisol in women with metastatic breast cancer. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62:337–345. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200005000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell EN, Messeri PA. Social support, disclosure, and use of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS & Behavior. 2006;10:263–272. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EE, Miller AL, Greene LI, Winiarski MG. Dialectical behavior therapy for substance abusers adapted for persons living with HIV/AIDS with substance use diagnoses and borderline personality disorder. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2004;11:202–212. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, El-Jawahri A, Prigerson HG. Update on bereavement research: Evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of complicated bereavement. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2006;9:1188–1203. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]