Abstract

Recent work on comorbidity finds evidence for hierarchical structure of mood and anxiety disorders and symptoms. This study tests whether a higher-order internalizing factor accounts for variation in depression and anxiety symptom severity and change over time in a sample experiencing a period of major life stress. Data on symptoms of depression, chronic worry and social anxiety were collected 5 times across 7 months from 426 individuals who had recently lost jobs. Growth models for each type of symptom found significant variation in individual trajectories. Slopes were highly correlated across symptom type, as were intercepts. Multilevel confirmatory factor analyses found evidence for a higher-order internalizing factor for both slopes and intercepts, reflective of comorbidity of depression and anxiety, with the internalizing factor accounting for 54% to 91% of the variance in slopes and intercepts of specific symptom sets, providing evidence for both a general common factor and domain-specific factors characterizing level and change in symptoms. Loadings on the higher order factors differed modestly for men and women, and when comparing African-American and White participants, but did not differ by age, education, or history of depression. More distal factors including gender and history of depression were strongly associated with internalizing in the early weeks after job loss, but rates of change in internalizing were associated most strongly with reemployment. Findings suggest that stressors may contribute in different ways to the common internalizing factor as compared to variance in anxiety and depression that is independent of that factor.

Keywords: Comorbidity, Trajectories, Depression, Anxiety, Stressful Events

Depressive and anxiety disorders co-occur frequently. In the National Comorbidity Survey Replication, 12-month prevalence diagnoses of Major Depressive Episodes were correlated .62 with Generalized Anxiety Disorder and .52 with Social Anxiety Disorder (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005). Most studies of comorbidity have focused on diagnoses made at a single point in time, although a few investigators have recently studied co-occurrence of disorders or symptoms as they manifest over a period of years (Olino, Klein, Lewinsohn, Rohde & Seeley, 2010). In this paper we take up the question of whether and why symptoms of anxiety and depression follow similar or different trajectories over a period of months following a major stressful life event, in this case the sudden loss of employment. Although stressful events are strongly associated with and prospectively predict both depressive disorders and anxiety disorders (Paul & Moser, 2009), there is little research as yet on whether stressful events increase risk for co-occurring anxiety and depressive symptoms, whether these symptoms grow, stabilize or remit in parallel in the months following the event, and what might account for patterns of change.

Models of Comorbidity

Investigators have approached comorbidity from two different modeling perspectives. Some have considered comorbidity to reflect a true hierarchical model. In such a model, elements at lower levels are completely subsumed by elements at higher levels. Clark and Watson (1991) developed one of the first hierarchical models of co-occurring internalizing symptoms, hypothesizing a tripartite structure with three components: a general distress factor common to both depression and anxiety, a physiological hyper-arousal factor specific to anxiety, and an anhedonia factor specific to depression. Based on this, Clark and Watson also proposed a diagnosis of mixed anxiety-depression. Watson (2005) expanded this model for the internalizing disorders, suggesting that an overarching class of mood and anxiety disorders subsumes three subclasses involving bipolar disorders, distress disorders, and fear disorders. A number of investigators have advanced and studied other variants of hierarchical models to explain associations among contemporaneous symptoms or diagnoses (Brown, Chorpita & Barlow, 1998; Kreuger & Finger, 2001).

Several studies have used confirmatory factor analysis to test whether diagnostic or symptom measures cluster into latent variables, finding support for such clusters when analyzing data involving contemporaneous diagnoses (Miller et al., 2008; Naragon-Gainey, 2010). Investigators have in some cases expanded the model to include externalizing disorders, which appear to fall into a separate latent factor that is moderately correlated with the higher-order internalizing factor (Slade & Watson, 2006). Not all studies have replicated this hierarchical model, however. Beesdo-Baum et al. (2009) recently reported a failure to replicate the higher order internalizing factor in a sample of adolescents and young adults, and Miller et al. (2008) found that substance abuse disorders cross-loaded with an anxious-misery factor in a sample of Vietnam veterans, violating the assumptions of a strict set of hierarchies.

Simms, Grös, Watson, and O'Hara (2008) proposed a bifactor model as an alternative to the true hierarchy model. Bifactor models do not assume hierarchy; rather they posit that associations among mood and anxiety disorders reflect two types of latent processes: a broad, more general process that leads to associations among all disorders, and a set of more limited processes that lead to higher associations among specific subsets of disorders. Chen, West, and Sousa (2006) note several advantages of the bifactor model, including the capacity to study measurement invariance across both general and domain-specific factors (such as comparing models for males and females), and to study the causes and effects of domain-specific variation independent of the more general factor.

Sims et al. (2008) were perhaps the first to apply a bifactor model to measures of anxiety and depressive symptoms, using data from three different samples of community adults, psychiatric patients and undergraduate students. They found that a general factor accounted for between 40% and 50% of the item variance, and a set of 13 specific factors together accounted for another 25% to 28% of the remaining variance. They were able to show that this structure replicated across all three groups. Based on this work, we predicted that a model incorporating both common and domain-specific processes would best characterize variation in trajectories of depression and anxiety following job loss.

Modeling Comorbidity over Time

Most research on higher-order characterization has focused on symptoms or diagnoses measured at one point in time, although a few investigators have begun to study patterns of symptom co-occurrence more dynamically to understand how they might change over time. Krueger, Caspi, Moffit, and Silva (1998) found that measures of ten common disorders could be modeled with two higher-order latent variables that distinguished internalizing and externalizing disorders in 18 year olds. In addition, these two latent variables were again found on follow-up at age 21, and the stability of these higher-order variables was high across the three year period. This suggests that the general internalizing factor found by other investigators is relatively stable, but provides no information about the stability of more specific factors which were not modeled by Krueger et al. (1998).

Olino et al. (2008) addressed this issue directly, collecting diagnostic data on depressive and anxiety disorders four times from childhood through young adulthood, on a community sample followed over 15 years. Their data supported a three factor model involving a common factor loading on both diagnoses at all four waves, and two disorder-specific factors loading only on depression or anxiety across all four waves. This model provided evidence for long-term stability of both the common and unique factors, and found no evidence that disorders became more differentiated over early adulthood.

Olino et al. (2010) more recently used latent class growth analyses to model trajectories of depressive and anxiety disorders in these data, identifying six trajectory classes that included change in both depression and anxiety. Comorbidity varied across classes, with some evidence that dynamic fluctuations in disorders operated in parallel for some groups but not for others. These findings suggest that studying trajectories that characterize both stability and change in anxiety and depression can provide a more detailed picture of the dynamics of symptom co-occurrence over time, necessary for understanding how risk and protective factors operate to shape both depression and anxiety.

Comorbidity at Shorter Time Scales

Understanding the etiology of comorbidity will require attention to processes that operate at different time scales (Howe, 2004). Lewis and Granic (2000) introduced the distinction between mesodevelopmental and macrodevelopmental theories, the former involving processes that shape regulation of emotion over a time scale of weeks or months, the latter involving processes shaping emotional development over years. Most studies of the evolution of comorbidity over time have focused on macrodevelopmental time scales. The present study, however, focuses on comorbidity at mesodevelopmental time scales, characterizing anxiety and depressive symptom trajectories over a period of several months following the occurrence of a specific risk factor, in this case sudden involuntary loss of employment.

The effects of exposure to stressful events have been studied across a variety of time scales, but exposure to severe focal life events appears to have effects that operate at mesodevelopmental time scales. Longitudinal studies find that risk for major depressive episodes is elevated for only one to six months after an event, unless new stressful circumstances emerge (Kendler, Karkowski, & Prescott, 1998). Studies have consistently found contemporaneous and prospective associations between job loss and depression, including both depressive symptoms (Dew, Penkower, & Bromet, 1991) and diagnoses of major depressive episodes (Kendler et al., 1998). Studies of anxiety are less frequent, but effects are consistent here as well (Paul et al., 2009). We have however been unable to locate any studies concerning whether job loss is associated with co-occurrence of anxiety and depression, either contemporaneously or prospectively.

We suggest two possible scenarios that could lead to comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms following a stressful life event. It is possible that one set of symptoms may precede onset of the other. There is evidence for this progression in macrodevelopmental studies which find that anxiety disorders, particularly GAD, emerge first during childhood or adolescence and tend to be followed by an increased risk for depressive disorders (Cole, et al., 1998). Similar staging may occur in mesodevelopmental time scales, such that anxiety arises immediately after a major stressful event, followed by depression if the stressful conditions show no sign of abating. It is also possible that common etiologic mechanisms are at the root of both types of disorders. These may include common neurobiological mechanisms involved in processing information about environmental threat, for example (Hariri et al., 2005). We know of no studies that look at the progression or co-occurrence of these disorders across mesodevelopmental time scales. In this study, we look at the patterns of development of anxiety and depressive symptoms when both sets of symptoms are present.

Stress and Comorbidity

Studies of stressful events suggest that these events may have effects that are both general and domain-specific. Given that such events are associated with both depression and anxiety, it is very likely that both of those responses often occur in the same individuals. As a result, trajectories of symptom onset, stabilization, and resolution are likely to occur in parallel for both depressive and anxiety symptoms. Rose et al. (2009), in one of the very few tests of this thesis, found evidence for conjoint trajectories of depressive and anxiety symptoms in cancer survivors followed for two years.

However, there is also evidence that various stressful events may have different characteristics that are associated with somewhat different responses. Kendler et al. (2003) found that major depressive episodes were more likely to follow events involving loss or humiliation, while clinically significant increases in anxiety followed events involving loss or danger. These findings were based on Brown and Harris's (1978) contextual assessment system for identifying and rating life events on various dimensions. Loss events included loss of persons, material possessions, health, or employment; humiliation included separation or breakup with partner and events involving rejection or direct verbal attack by a close tie or person in authority; danger included potential for future loss or recurrence of traumatic events. Keller, Neale, and Kendler (2007)also found that event characteristics were differentially associated with different subsets of depressive symptoms, such that interpersonal loss events were more strongly associated with anhedonia, sadness, and appetite loss, while failure events were more strongly associated with fatigue and hypersomnia. These findings suggest that severely stressful events will have effects on both general internalizing and on specific symptom domains, with the latter effects depending on variation in the nature of those events.

In this study we focus on loss of employment and its aftermath. Such events clearly involve loss on several fronts. Employment provides economic support, association with a network of co-workers or colleagues, and a way of fulfilling personal aspirations. Loss of employment is associated with an erosion of personal identity (Price, Friedland, & Vinokur, 1998), and can involve loss of contact with a work-related social network. Loss of income threatens other areas of goal attainment, including capacities to provide security for self and family. There is also substantial evidence that loss of employment is associated in American society with loss of self-value, and that unemployed individuals are often treated in devaluing ways by others, increasing exposure to humiliation (McFadyen, 1998). As a result, job loss is often characterized by forms of loss and humiliation that Kendler et al. found associated with risk for depression, as well as by threat to personal and family security, which have been associated with anxiety responses. Given a substantial literature linking job loss in general to both depression and anxiety (Paul & Moser, 2009), we hypothesize that individuals facing unemployment will show high rates of comorbid anxiety and depressive responses.

Risk Factors for Comorbidity

Most research on risk for comorbidity has focused on general demographic factors. Evidence is strongest for gender differences. In the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS: Kessler et al., 1999) gender was associated with both depression and anxiety disorders, including GAD and social phobia, with women showing higher rates of both mood and anxiety disorders. Kessler et al. (2005) used latent class analysis to identify seven patterns of comorbidity in diagnostic data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Four of these classes involved substantial comorbidity among depression and anxiety disorders, and all four were more prevalent for women. Olino et al. (2010), in their macrodevelopmental study of anxiety and mood disorders in a sample followed from adolescence for 15 years, also found higher representation of women in their latent class involving late onset anxiety and increasing depression.

Findings for age, education, and ethnicity are less consistent. Both age and education were associated with both forms of disorder in the NCS, with highest prevalence rates in the 25–34 year age group. Rates decreased monotonically as education levels increased (Kessler & Zhao, 1999). Rose et al. (2009) found that relatively older and better educated cancer patients were more likely to report more moderate levels of depression and anxiety, and more likely to show improvement in symptoms over the two year study period. However, in the NCS-R data, education only distinguished classes that differed on comorbid externalizing disorders, and younger participants showed higher prevalence rates for only two of the four internalizing comorbidity classes (Kessler et al, 2005).

Ethnicity has been found to be associated with depression, with African Americans showing significantly lower rates of mood disorders than whites (Blazer, Kessler, McGonagle & Swartz, 1994), but there have been mixed findings on the prevalence rates of anxiety disorders based on ethnicity. Kessler and Zhao (1999) failed to find significant differences among ethnicities, though Ruscio, et al. (2008) found that Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks had reduced odds of being diagnosed with social phobia. In the NCS-R, African Americans only showed lower prevalence in a class involving comorbidity with externalizing diagnoses.

Given the recurrent nature of major depression, it is also possible that prior depressive episodes may be related to risk for future comorbidity. This issue is complex: a number of studies find that risk for depressive episodes following severe life stressors is high for initial onsets, but diminishes after each recurrence (Mazure, 1998). Although some have suggested this reflects a reduction in the effects of stressors, Monroe and Harkness (2005) have noted that it may reflect the opposite, with weaker stressors increasing in potency for triggering depression, and therefore washing out the singular effects of more severe events in studies where only severe events are measured. This issue has not been studied in relation to comorbidity, although future anxiety disorders are associated with prior history of major depression (Karsten et al., 2011).

To our knowledge, there have been no studies as yet testing for individual differences in the strength, severity, or trajectories of comorbid conditions following loss of employment or any other major life event. As noted earlier, job loss is characterized by a number of risk factors that have been associated with both depression and anxiety responses more generally. However there is little research on whether these risk factors vary across subpopulations. Indirect evidence suggests the possibility that comorbidity is associated with changes in patterns of stressful events. Prior research has found that re-employment is associated with resolution of depressive symptoms (Ginexi, Howe, & Caplan, 2004), suggesting that resolution of this stressful context may also shape changes in comorbid anxiety. Based on this work, we hypothesize that general internalizing, if found, will be more prevalent for women. We make no predictions concerning the generality of higher-order structure for other demographic factors, but do include tests of generality across variation in age, education, ethnicity, and prior history of major depression, as all of these factors are associated with both depressive and anxiety disorders in other research. We also hypothesize that re-employment will lead to a resolution of symptoms. We make no predictions concerning association with unique variation in symptom sets after controlling for general internalizing, but include tests of such associations.

The Present Study

The present study had three goals. First, we estimated growth models to characterize variation in trajectories based on symptom scores collected five times in the seven month period after loss of employment. These data, collected from a sample of 426 adults initially interviewed within six weeks of job loss, allowed us to estimate both linear and quadratic components of trajectories for symptoms of depression, worry, and social anxiety.

These analyses showed that parameters characterizing these trajectories were highly correlated across the different symptom areas. As our second goal we then conducted two-level confirmatory factor analyses of the combined set of growth parameters for all three symptom measures, in order to identify the model best explaining the associations among growth parameters. We tested hypotheses that anxiety and depressive reactions would co-occur, and that the patterns of change and stability in the symptoms over the period following job loss would commonly be parallel. However, based on findings concerning both common and unique components of internalizing, we tested hypotheses that depression and anxiety trajectories do not always move strictly in parallel.

As our last goal we studied whether common and unique variations in trajectories were associated with participant characteristics including age, gender, ethnicity, education, prior history of major depression, and re-employment.

Method

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the George Washington University Institutional Review Board.

Participants & Recruitment

In order to assure a sample with adequate variation on important factors, we employed heterogeneous purposive sampling, a method designed to aid in generalization of results when random sampling cannot be implemented (Shadish, Cook & Campbell, 2002). In order to increase generalizability, we recruited this sample from a state-wide database which included rural, suburban and urban areas. In addition, this sampling method allowed us to recruit individuals from varying ethnicities, ages and both genders. We also oversampled African-American males in order for our final sample to have relatively equal numbers of males and females and of African-American and White participants.

Potential participants resided in one of six Maryland counties in the greater Baltimore-Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. We collaborated with the Maryland Department of Labor, Licensing, and Review to send out letters describing the study on a weekly basis to a random sample of all individuals applying for unemployment insurance within the last week. Recruitment continued from February 2007 to December 2008. Those interested in the study contacted the project directly and participated in an eligibility screening. Eligibility criteria included: a) unemployed for no more than 42 days at the time of first interview; b) had not been offered or received a new job or were not working in any job for more than 19 hours per week; c) did not quit previous job; d) had been laid off permanently; e) was not planning to retire in next two years; f) lost job was not seasonal; and g) the participant was able to speak and read English. Over a period of 22 months, 1,056 people were screened and 643 individuals met the eligibility criteria for the study. In cases where a potential participant was not eligible, the most common cause was too much time since job loss. Eligible individuals were given a short description of the study and invited to participate in an interview in or near their home. Of those eligible, 217 did not participate; 82% of these because interviewers were unable to schedule an interview within the required time frame, or because the individual had found employment prior to the interview.

The final sample consisted of 426 individuals. The sample included 220 women and 206 men ranging in age from 19 to 81 (mean age = 46). Forty-seven percent were white, 42% African-American, 6% more than one race, 2% Hispanic, and 3% unknown or other (American Indian, Asian, Pacific Islander). On average, participants had completed 14.4 years of education (SD = 2.64), ranging from 8 to 20 years. Around 28% of participants lived alone, 24% lived with other adults, 19% lived only with a spouse or partner, and 29% lived with children. Median household income was $63,000 before job loss, and $17,000 after, with 38% of the sample reporting no income after job loss. Based on 2008 weighted average poverty thresholds (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010), 6% of participant households were below poverty line before job loss, with 51% of the sample below poverty threshold after job loss.

Data Collection

Participants completed a series of five interviews over the seven months following loss of employment. The initial interview took place in person, generally in the home of the participants; follow-up interviews were conducted by telephone. In-person interviews ranged from two to four hours and follow up interviews from 30 minutes to two hours. All elements of data collection were computer administered, some interviewer administered and some self administered. Time 2 interviews were scheduled 12 weeks after the date of job loss, and the remaining interviews were scheduled every 6 weeks. Interviews 2 through 4 had to be completed within two weeks of the target date. The interview period for Time 5 was extended beyond this two week window in an effort to increase the number of completed assessments six months post job loss. The average time between the T4 and T5 interviews was therefore 8 weeks. Eighty-five percent of the participants completed the Time 2 interviews, 74% the Time 3 interview, 72% the Time 4 interview, and 88% the Time 5 interview. Participants were compensated $15 per hour for their time.

Measures

The initial interview encompassed a broad range of variables for characterizing the job loss event and subsequent economic and housing conditions, as well as assessments of personality factors. Mood and anxiety symptoms were assessed through questionnaire and through diagnostic interviews. Participants also provided saliva samples for analysis of DNA.

In this report we focus on data from symptom measures of depression, social anxiety, and worry collected during all five waves of data collection. All of these measures were self-administered on laptops via computer-assisted programming during the in-home interview. During telephone follow-ups these measures were administered verbally by the interviewer.

Depression symptoms

To measure depressive symptoms, we used an abbreviated version of the Center for Epidemiological Study Depression Scale (CES-D) which was developed to measure symptoms of depression in the general population (Radloff, 1977). This instrument asks the individual to indicate on a four point scale how often they have experienced various symptoms in the past week. For example, one item asks the individual how often “I felt everything I did was an effort.” We administered the full 20 item measure during the first wave of data collection, and a shorter 12 item version at each of the four subsequent waves. Time one total scores for the full and abbreviated versions of the measure were correlated .98, indicating excellent comparability. Only the shorter version was used in the analyses for this study for all five waves. Previous research has also used abbreviated versions of this scale. Cole, Rabin, Smith and Kaufman (2004) validated a ten item version of the CES-D which demonstrated a wide range of depressive severities and measured all aspects of the theoretical construct found in the full form. In this study, we used all ten items used by Cole et al. and included two additional items, “I felt depressed” and “I felt sad,” in order to be able to compare findings to those from other studies using this set of 12 items in unemployment samples (Howe, Levy, & Caplan, 2004). Consistent with previous research, in this sample we found Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.75 to 0.89 for waves 1 through 5 for our abbreviated scale.

Chronic worry symptoms

The Penn State Worry Scale was used to assess general levels of worry (Meyer et al., 1990). This 16-item instrument asks participants to rate items such as, “I know I should not worry about things, but I just cannot help it,” and “once I start worrying, I cannot stop” on a 5 point scale ranging from “very typical” to “not at all typical.” This measure has shown high internal consistency and good test-retest reliability (Meyer et al., 1990). It has been used to reliably distinguish cases of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (Behar, Alcaine, Zuellig & Borkovec, 2003; Fresco, Mennin, Heimberg & Turk, 2003), and as an index of symptom change in clinical trials of interventions for GAD (e.g. Katzman et al., 2008). The range for Cronbach's alpha for this measure was from 0.75 to 0.88 in the current study.

Social anxiety symptoms

In order to measure participants' characteristic symptoms of social anxiety, The Brief Social Phobia Scale (BSPS) was used (Davidson, Miner, De Veaugh-Geiss, Tupler, Colket & Potts, 1997). This 18 item measure consists of three subscales; fear, avoidance, and physiological arousal, which were combined into a total score. The BSPS asks participants to rate on a 5-point rating scale their level of fear or anxiety in a number of different situations, including, “speaking in public or in front of others” and “talking to people in authority.” This measure also asks participants to rate how often they tend to avoid each situation on a 5-point rating scale from “never” to “always.” The BSPS has shown high levels of reliability and validity, as well as test-retest reliability and internal consistency (Davidson et al., 1997). It has been used to reliably distinguish subjects with Social Anxiety Disorder from subjects with subthreshold levels of SAD and control groups (Filho, et al., 2009). The Cronbach's alpha for this ranged from 0.92 to 0.95 in the current study.

Prior history of depressive disorder

Lifetime history of depression was assessed using the computerized depression module of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Kessler & Ustun, 2004) during in-home interviews at the first wave of data collection. The CIDI is a well-established structured clinical assessment that maps symptoms reported during the interview onto DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. This format, designed for lay interviewers, has demonstrated good test-retest reliability (Wittchen, 1994) and the lifetime version has demonstrated excellent positive predictive value (Booth et al.,1998). Standard training materials and procedures were used to train interviewers on administration of the CIDI. Interviews were recorded and reviewed by supervisory staff, who followed a quality control protocol to insure the assessment was administered properly. A binary index was constructed for presence of lifetime history of major depressive episodes by assigning a 1 to all individuals who met CIDI criteria for lifetime history, excluding those who met these criteria solely because of the presence of a first episode around the time of job loss. All others were assigned a score of 0.

Financial status and demographics

Demographic information was collected at Time 1 through a self-administered questionnaire including items describing their gender, education, age, and ethnicity. To gather information about financial status, participants were asked to estimate their income prior to job loss. Questions on re-employment were administered by interview during follow-up.

Results

We conducted all analyses with MPLUS software, Version 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010). There were a few missing data points within each wave due to participant refusal to answer specific questionnaire items. All scale scores were prorated when less than 20% of items were missing; otherwise scores were considered missing. This led to missing rates of around 1% across all three measures across all waves. We used the MPLUS option for full information maximum likelihood (assuming an MAR mechanism) to handle this form of missingness. Given that symptom data were somewhat skewed, we used the MLR estimation procedure for all analyses, to produce robust standard errors. Chi-square estimates from nested models based on MLR cannot be directly compared; we therefore used scaling factors provided by the program to calculate a scaled difference chi square test statistic (Satorra & Bentler, 2001) for comparing such models.

Measurement invariance

Some investigators have recently found evidence that symptom scales, particularly those involving worry, may not show invariance across ethnic groups (Carter et al., 2005; Hambrick et al., 2009), which could lead to problems in interpreting findings in samples including people of different ethnic backgrounds. We therefore tested each of our three scales for measure invariance, comparing our African-American and White samples. We used multilevel confirmatory factor analysis in order to include data from all five waves, using the COMPLEX option in MPLUS to adjust for non-independence of repeated measurements. Although it does not include random effects, this analysis is considered multilevel because measures are nested within participant across waves. We compared models that fixed all item loadings to be equal across ethnic group to models that allowed all item loadings to be free across groups. These analyses found evidence for both configural and metric equivalence (Vandenberg & Lance, 2000) for all three of our symptom measures (for CES-D, Wald Test (78) = 16.61, p = .12; for PSWQ, Wald Test (15) = 13.62, p = .55; for BSP, Wald Test (17) = 18.53, p = .36). These results supported the further use of these measures, given evidence for equivalence across ethnic groups.

Symptom severity

To provide a benchmark for assessing the overall severity of symptoms observed in this sample, we compared means and distributions of symptom measures at the first interview to other studies of community samples. With a sample mean on the CES-D of 15.4, 42 percent of participants scored above the standard cut-off score of 16 for possible depression (Radloff, 1977; Roberts & Vernon, 1983). Combining data from two larger community samples (Gillis, Haaga & Ford, 1995; Van Rijsoot, Emmelkamp, & Vervaeke, 1999), we calculated a mean of 40.8 and a 70-th percentile benchmark of 47 and above on the PSWQ. The PSWQ mean for our sample was 45.5, with 37% scoring at or above 47. Our sample had a mean score of 18.5 on the BSPS, with 38% scoring at or above the cutoff of 21 recommended by Osório, Crippa & Loureiro (2010). Overall, these findings indicate clinical levels of depression, worry, and social anxiety in a substantial proportion of this sample.

Growth models for each symptom set

Timing of measurement was somewhat variable within each wave, and particularly so for the final wave. We specified growth models for each symptom set using both variable and fixed times of measurement, the former requiring more complex random effects models. Results were generally similar, and we chose the fixed times of measurement model for all remaining analyses, because the random effects model that is required to estimate varying times of measurement was difficult or impossible to include in the higher-order analyses we describe later. We set the date of job loss as the intercept to provide a common point of origin for all participants and used loadings that scaled time units in terms of 4 week durations. Loadings for the slope factor were set at 1.17, 2.90, 4.37, 5.80, and 7.43 for waves 1 through 5, respectively. These loadings were based on the average time since job loss for each wave of data collection. Use of the full-information maximum likelihood option insured that all data points contributed to the analyses, regardless of whether a participant had missed one or more measurement occasions.

We first specified growth models that included fixed and random effects for intercept, linear growth, and quadratic growth. We then estimated reduced models forcing the quadratic growth variance to zero, and tested comparative model fit, using the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi square test. If the reduced model did not differ significantly from the full model, we repeated this strategy to test fixed and random effects for each parameter. We then selected the best fitting reduced model for each symptom set. Table 1 reports parameters and fit indices for these final models.

Table 1.

Unstandardized parameters and model fit indices from final growth models

| Fixed Effect Parameter | Standard Error | Variance Parameter | Standard Error | χ2(df) | P | RMSEA | SRMR | CFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression | 13.85 (9) | .13 | .036 | .023 | .99 | ||||

| Intercept | 10.299*** | .521 | 40.505*** | 4.719 | |||||

| Linear | −.856*** | .231 | .514* | .136 | |||||

| Quadratic | .073** | .025 | --- | ||||||

| Worry | 3.66 (9) | .93 | .000 | .016 | 1.00 | ||||

| Intercept | 45.466*** | .839 | 156.832*** | 12.079 | |||||

| Linear | −1.277*** | .291 | .772*** | 0.206 | |||||

| −Quadratic | .095** | .031 | --- | ||||||

| Social Anxiety | 12.34 (10) | .26 | .023 | .033 | 1.00 | ||||

| Intercept | 18.543*** | .558 | 99.344*** | 10.349 | |||||

| Linear | −.217** | .069 | .689* | 0.292 | |||||

| Quadratic | --- | --- |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Fixed intercept effects estimate the average symptom levels at the beginning of the period of job loss. These are all significant, and as noted earlier are elevated in comparison to other community samples not experiencing job loss, consistent with the large body of work finding elevations in depression and anxiety symptoms after job loss. Fixed linear slope effects estimate the average increase or decrease in symptom scale points over time (in this case per 4 weeks). All average slopes are significant and negative, indicating an average decrease in all three types of symptoms over the study. Fixed quadratic effects reflect nonlinear change. Fixed quadratic effects for depression and worry were significant and positive, indicating some deceleration in downward change. Variances of intercept and linear slope were significant for all three types of symptoms, indicating that symptom levels and linear trajectories systematically varied across study participants. Variance of the quadratic parameter was not significant for any symptom set, suggesting that the rates of downward deceleration did not differ across participants. Average trajectories based on the fixed effect parameters are illustrated in Figure 1. To provide some perspective on rates of change, we calculated the proportion of the sample still above clinical cutoff levels at T5. Based on actual symptom scores, 29% remained above cutoff for depression, 28% for worry, and 31% for social anxiety.

Figure 1.

Average trajectories for individual symptom sets. Symptom scores have been standardized with intercept mean of one and standard deviation of one, to allow comparisons on a standard metric.

Correlations among growth parameters

We next specified growth parameters for all three symptom sets in the same model, using trimmed versions that set the variances of all quadratic terms and the quadratic mean for social anxiety to zero. This model allowed us to estimate correlations among the growth parameters across the three symptom sets. As results in Table 2 illustrate, the intercepts were very strongly correlated among the three symptom areas, as were the slopes.

Table 2.

Correlations among latent growth and intercept variables1

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Depression Intercept | |||||

| 2 | Chronic Worry Intercept | .80*** | ||||

| 3 | Social Anxiety Intercept | .72*** | .67*** | |||

| 4 | Depression Slope | −.20 | −.27** | −.18 | ||

| 5 | Chronic Worry Slope | −.15 | −.05 | −.05 | .87*** | |

| 6 | Social Anxiety Slope | −.07 | −.14 | .01 | .66*** | .74*** |

p < .05;

p < .01

p < .001

Model fit indices: χ2(91) = 201.90, p < .000; RMSEA = .054; SRMR = .031; CFI = .97.

Higher-order model

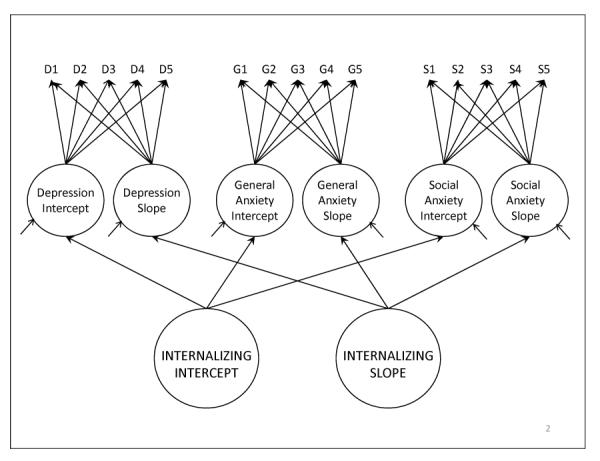

This pattern of correlations strongly suggested that growth trajectories of the three symptom sets would be accounted for in part by more general higher-order factors. To test for higher-order structure, we specified a three-level model, illustrated in Figure 2, with two latent factors. The first factor, labeled the internalizing intercept, loaded on the depression, worry, and social anxiety intercept latent variables that were in turn estimated from the 15 respective symptom scores across the five waves of measurement. The second factor, labeled the internalizing slope, loaded on the respective slope latent variables of the three specific growth models. We reasoned that the symptom-specific loadings on these two factors should be equal, allowing us to interpret these latent variables as intercept and slope of the same higher-order construct. We therefore constrained these to be equal; for example, the loading of depression intercept on internalizing intercept was constrained to equal the loading of depression slope on internalizing slope. As a result, each symptom set contributes the same proportion of variance to both the intercept and the slope latent factors. This eliminates situations where one symptom set might contribute more strongly to the latent intercept, while a different symptom set is represented more strongly in the latent slope factor. We compared this constrained model to a model allowing these parameters to be free. The constrained model had no significant effect on model fit, supporting its use (change in -2LL(2) = 4.45, p = .11). We also included a fixed effects estimator for the mean quadratic change in chronic worry and depression to improve model fit.1

Figure 2.

Three level model with higher-order latent variables for internalizing intercept and linear growth. D1 – D5 indicate measures of depression symptoms from waves 1 through 5; G1 – G5 indicate measures of chronic worry; S1 – S5 indicate measures of social anxiety. Loadings on each symptom set intercept are constrained to 1; loadings on each symptom set slope reflect fixed times of measurement, and are therefore constrained to mean time since job loss for each wave of data collection, in units of 4 weeks duration (1.17, 2.90, 4.37, 5.80, and 7.43 for waves 1 through 5, respectively).

Analogous to bifactor models, this three-level model partitions slope and intercept variance into common and unique components, with separate unique variances estimated for each of the depression, worry, and social anxiety growth factors. Model fit indices showed good fit to the data [χ2(101) = 211.92, p < .001; CFI = .973, RMSEA = .051; SRMR = .034). Factor loadings, reported in Table 3, were all strong and significant. Estimates of variance accounted for indicate that the higher-order factors account for much but not all of the variance in the symptom-specific intercept and growth factors, consistent with other studies that have found both common and unique effects. Slopes and intercepts were associated for the common factors (r= −.20, p < .05). This is likely due to the sampling period starting soon after a major stressful event; those who were most affected would have high intercepts, but would also be more likely to show a return to baseline over time, compared to those who were not as affected by the event. None of the slopes and intercepts for the unique factors were correlated with each other within symptom set, suggesting that a pattern of reaction and resolution may be limited to the general internalizing factor.

Table 3.

Loadings on higher-order internalizing factors for entire sample

| Unstandardized Factor Loading | Standard Error | Standardized Factor Loading | Variance accounted for(R2) by Higher-order factor | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalizing Intercept | ||||

| Depression Intercept | 1.000 | --- | .929 | 86.3% |

| Chronic Worry Intercept | 1.787*** | .138 | .811 | 65.8% |

| Social Anxiety Intercept | 1.357*** | .091 | .772 | 59.6% |

| Internalizing Slope | ||||

| Depression Slope | 1.000 | --- | .735 | 54.0% |

| Chronic Worry Slope | 1.787*** | .138 | .953 | 90.8% |

| Social Anxiety Slope | 1.357** | .091 | .751 | 56.5% |

Loadings for depression intercept and depression slope were constrained to 1 for model identification, and to establish scaling of higherorder latent variables.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Generality of common and unique factors

As noted earlier, we found evidence for measurement invariance across ethnicity for each of our individual symptom measures. However, model invariance can also differ at higher levels of structure. We therefore used multiple group analysis methods in MPLUS to test whether this factor structure was stable across gender, age, education, ethnicity, and lifetime history of major depression. We dichotomized age and education at their medians (median age = 47; median education = 14 years). We tested variation by ethnicity by comparing African-American and White participants that together made up 88% of the sample. We first specified and estimated models where all loading parameters were free to vary across the relevant grouping variable. We then specified models that constrained all loading parameters to be equal across groups, and compared relative model fit using the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square test.

There was no evidence of group differences based on age, education, or lifetime history of major depression. Loadings did differ significantly for gender (scaled χ2 difference = 7.10, df = 2, p < .03) and for ethnicity (scaled χ2 difference = 10.44, df = 2, p < .006). Follow-up analyses reported in Table 4 indicated that loadings differed significantly for males and females only on worry, with women having somewhat higher loadings for that set of symptoms. For ethnicity, loadings differed significantly only for social anxiety, with African Americans having somewhat higher loadings. Although these differences reach standard levels of significance, they are modest in size.

Table 4.

Differences in standardized factor loadings by gender and ethnicity

| Male | Female | African American | White | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | ||||

| Depression | .925 | .925 | .938 | .938 |

| Chronic Worry | .770a | .836b | .817 | .817 |

| Social Anxiety | .768 | .768 | .817c | .720d |

| Slope | ||||

| Depression | .716 | .716 | .707 | .707 |

| Chronic Worry | .925a | .951b | .930 | .930 |

| Social Anxiety | .730 | .730 | .785c | .680d |

Note: parameters with different subscripts differ significantly from each other (as tested on unstandardized parameters).

Associations with age, education, ethnicity, gender, and history of major depression

To explore the association of sample variables with symptom growth, we specified and estimated seven models. In all cases age and education were included as continuous variables, gender as a dummy variable (coded 0 for males, 1 for females), ethnicity as two dummy variables, one contrasting African Americans (coded 1) with Whites (coded 0), the second contrasting all other ethnic categories as a group (coded 1) with Whites (coded 0), and lifetime history of major depressive episode as a dummy variable contrasting presence (coded 1) with absence (coded 0). Three of these models included these variables in a multiple regression as predictors of each symptom set's growth parameters, not including any other symptom set. We then estimated a model regressing the higher-order internalizing intercept and slope factors on these variables. Given that findings concerning gender and ethnic differences in loadings were relatively modest, we elected to conduct these analyses with the entire sample, rather than within these subgroups. Finally, we estimated three models that regressed the unique variance in the growth parameters of each symptom set on these variables after controlling for variance due to the respective higher-order internalizing factors. In all cases the relevant intercept was included in the regression predicting slope, to control for initial status. Overall, this strategy allowed us to study whether these variables were associated with the general common factors in similar or different fashion as compared to their association with unique variance in growth in each specific symptom set.

Results of the analyses are summarized in Table 5; all coefficients reflect effects after controlling for all other variables. Gender was associated with the intercepts of worry and social anxiety, as well as the intercept of the general internalizing factor, with women reporting higher levels in each case. Women were also somewhat more likely to report chronic worry above that associated with general internalizing. Age and education were significantly associated with intercepts for all three symptom sets and internalizing, with older and more highly educated participants reporting lower levels of symptoms. Ethnicity was not associated with any specific symptom set intercepts directly. However minority participants in general reported more depression and lower levels of chronic worry than Whites after accounting for general internalizing. History of major depressive episodes was strongly associated with all three symptom sets and with internalizing. It remained associated with depression after controlling for externalizing, but not with worry or social anxiety.

Table 5.

Standardized regression coefficients for variables predicting slopes and intercepts for symptom sets, common effects, and unique effect.

| Predictor | Depression | Chronic worry | Social anxiety | Internalizing | Depression (Unique) | Chronic worry (unique) | Social anxiety (unique) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized regression coefficients predicting intercept latent variables | |||||||

| Age | −.11* | −.10* | −.13* | −.12** | −.02 | −.05 | −.07 |

| Education | −.14* | −.11* | −.16** | −.16** | −.03 | −.02 | −.09 |

| Women vs. men | .20 | .48*** | .30*** | .36*** | −.10 | .36*** | .12 |

| AA vs. White | .17 | −.16 | .00 | −.05 | .22* | −.29** | −.07 |

| Other vs. White | .20 | −.24 | −.07 | −.04 | .34* | −.32* | −.07 |

| History of MDE | .88*** | .67*** | .49*** | .85*** | .45*** | .21 | .00 |

| Standardized regression coefficients predicting slope latent variables | |||||||

| Age | .10 | −.04 | −.09 | −.03 | .14* | −.01 | −.07 |

| Education | .00 | −.08 | .09 | −.08 | .05 | −.02 | −.05 |

| Women vs. men | −.20 | −.46** | −.04 | −.21 | −.11 | −.46** | .07 |

| AA vs. White | .37* | .31 | .02 | .24 | .31* | .22 | −.10 |

| Other vs. White | −.14 | .32 | −.32 | −.01 | −.17 | .50* | −.34 |

| History of MDE | −.08 | −.28 | −.03 | −.11 | −.09 | −.40* | −.02 |

| Intercept latent variable | −.15 | .08 | .01 | −.13 | −.15 | .26* | .03 |

| Satorra-Bentler χ2 difference based on comparison of models with regression parameters free or fixed to zero (df =12) | |||||||

| 87.52*** | 85.43*** | 64.78*** | 100.55*** | 46.31*** | 38.57*** | 19.57 | |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

There were fewer significant associations with the slope latent variables. Women's reports of chronic worry grew more slowly or decreased more quickly than those of men, and this held even after controlling for the general internalizing slope factor. Depression slopes by themselves were less likely to decline or more likely to increase for African Americans as compared to Whites, even after controlling for internalizing. Older and non-African-American minority participants showed slower resolution of depression, but only after controlling for internalizing.

Slope associations with re-employment

We repeated the analyses of slopes with the addition of a variable reflecting re-employment by T5, using the smaller subsample (N = 372) that had participated in that wave. Around 64% of the sample was re-employed by that time. Re-employment was associated with resolution of depression (β = −1.04, p < .001) and worry (β = −.35, p < .05), as well as overall internalizing (β = −.58, p < .01). Similar associations were found for depression (β = −.97, p < .001) but not worry after controlling for internalizing. Findings also suggested that re-employment rates may mediate the association of minority status with slopes.2 Re-employment rates were significantly associated with African-American versus white status (β = −.76, p < .01), with 52% of the African Americans re-employed at T5, compared with 70% of the whites. Inclusion of re-employment in the regression reduced associations of this variable to nonsignificance for both depression slopes in general and after controlling for internalizing. Associations of age with unique depression slopes were also reduced to nonsignificance. No other associations with slopes were affected. We also explored whether time to re-employment was associated with slopes for this subsample. This variable was not associated with slopes of any of the three symptom sets. Models including internalizing failed to converge for this variable.

Discussion

Our findings support growing evidence for hierarchical structure in the mood and anxiety disorders, and provide one of the first tests of such structure using longitudinal data and modeling growth over a seven month period following a major stressful life event. Variation in symptom trajectories could be partitioned into that related to a single more general internalizing factor, and that remaining within specific diagnostic symptom clusters after accounting for that general factor. This held true for estimates of both intercept and slope components of growth trajectories, with general factors accounting for a majority of the variance in both the intercepts and slopes of depression, worry, and social anxiety symptoms.

What might account for this pattern of findings? In terms of descriptive nosology, these findings bear on Watson's distinction between fear and distress disorders. Correlations in Table 2 are slightly higher between depression and chronic worry than between those factors and social anxiety, consistent with this distinction. However all three correlations are very robust, suggesting that the distinction for these data is weak at best. This is consistent with recent failures to find support for Clark and Watson's (1991) tripartite model of symptoms; several studies using confirmatory factor analysis have now found muted distinctions between anxiety and depression constructs which are however highly correlated (Buckby et al, 2008), suggesting that both constructs are part of a higher-order continuous factor.

These findings are more consistent with a common/unique model (Sims et al., 2008). In this case the same symptom score is simultaneously part of both a general factor and a symptom-specific factor. Both classification dimensions are necessary for a complete description of symptom presentation, and neither is more central than the other.

From an etiologic perspective, this suggests that depression and anxiety symptoms may be driven by a set of mechanisms that have both common and symptom specific elements. We speculate that this may reflect two different stress response mechanisms. The first mechanism involves general emotional dysregulation, and is not specific to a particular emotional response system. Biological underpinnings of this mechanism likely involve the amygdala-HPA axis, a phylogenetically more primitive system that is involved in a range of emotional reactions including depression, anxiety, and irritability. This system appears sensitive to the presence of simple threatening stimuli, and may be triggered by a wide range of stressful contexts, with crude but fast processing of stimuli into simple distinctions of threat versus no threat. Operation of this system would contribute primarily to the general internalizing factor found in this study, consistent with Davidson's (1998) speculations about comorbidity, and with the concept of general negative affect found in the tripartite model.

The second response system involves more nuanced processing of stressful contexts, with finer discrimination along the lines of Kendler et al's dimensions of loss, humiliation, or danger. Stressful events vary in terms of objective characteristics involving permanent loss or evidence for likelihood of future loss or adversity. Differential sensitivity to these stimuli is also likely, leading to variation in appraisal of threat. This system engages in more complex processing, underpinned by cortical activity. Elements of permanent loss would be more likely to push the system towards sadness, while elements of impending threat would enhance worry and anxiety. This is consistent with Beck's model of differential cognitive processing involved in depression or anxiety, and with Lazarus's model of emotional specificity to different stressful contexts. This more complex system would contribute both to the general internalizing response, through activating the first system, and to more symptom-specific responses that are activated or suppressed on top of the generalized response.

Recent theories advanced to account for comorbidity of anxiety and depression have focused more on this second response system (Shankman & Klein, 2003), as does the regulatory process model of comorbidity advanced by Klenk, Strauman, and Higgins (2011). These models emphasize distinctions in cognitive processing with biological foundations in the neocortex, but pay less attention to the effects of variation in stressful contexts. We suggest that both will be important to consider in any complete model of comorbidity.

Our findings also point to the importance of studying the dynamics of symptom change over time and focusing on mesodevelopmental time scales, suggesting that the intercept and slope components of the growth trajectories are themselves shaped by somewhat distinct processes. In this sample, variation in the intercept is probably influenced by both contextual factors, such as the nature and severity of the job loss event, and more distal factors, including personality characteristics, or the interaction of both stressors and personality. Findings concerning the association of various demographic characteristics suggest that more distal factors may be more relevant for the general internalizing intercept than for the independent specific symptom set intercepts. Age, education, gender, and history of major depression are all significantly associated with the general internalizing intercept, but only gender and history of depression continue to be associated with the specific intercept factors independent of the general intercept factor. In addition, gender has opposite associations with the unique depression and worry intercepts, with women reporting more chronic worry but less depression after controlling for internalizing.

Findings for ethnicity appear to contradict this thesis, given that ethnicity is associated with the unique depression and worry intercepts f, but not with the general internalizing intercept. This may however reflect the possibility that African-American and other minority participants are experiencing higher levels of stressors following the job loss, such that ethnicity is operating as a proxy for this more proximal factor. This is consistent with findings from another study of recently unemployed individuals conducted in the same geographic region: in that study Howe, Levy & Caplan (2004) found that African Americans reported significantly higher rates of stressors in the period immediately after job loss, as compared to White participants. However, this thesis would require that African Americans be exposed to different forms of stressors, given that they report higher levels of unique depression but lower levels of chronic worry, after controlling for general internalizing. This could reflect more exposure to immediate loss and less exposure to threat of future adversity, in line with Kendler et al's findings concerning differential effects of these different forms of stressful events. It could also reflect different patterns of appraisal. Given historical patterns of discrimination, employed minority participants are more likely to be moving out of poverty, and therefore may be more likely to experience layoff as a loss of aspirations, with less focus on the possibility of future adversity.

The picture differs for symptom change captured by slope parameters. In this sample slopes of change in the three unique symptom sets are uncorrelated with their estimated intercepts, suggesting that processes shaping these slopes will differ from those shaping the intercept. The correlation of intercept and slope is small but significant for the general internalizing factor, indicating some possible overlap in causal variables. Proximal or distal variables that influence the intercept may be less relevant for predicting patterns of change, and in this case there are fewer significant associations between demographic factors and slope variance, after controlling for the relevant intercept. Rates of change in symptoms over this period may be more related to variables changing during the course of the study, such as continuation or resolution of stressful economic, housing, and employment circumstances, than to distal factors. This is consistent with findings that re-employment by the end of the study is a strong predictor of reductions in general internalizing. Re-employment may also be appraised by the individual as regaining a lost source of income and identity, leading to more reduction in depressive symptoms above and beyond that for general internalizing.

This study has a number of limitations that need to be considered. The sample is constituted of individuals who have experienced a major stressful life event, and who continue to be exposed to stressful economic conditions. This extends previous work on comorbidity, but it may also set constraints on the applicability of these findings to individuals who are not experiencing such conditions. The sampling frame for the study was purposive rather than random. This allowed us to accrue a sample that varied substantially in terms of age, education, gender, and ethnicity, but cannot be considered representative of all job seekers. For example, the use of lists of people applying for unemployment insurance may fail to include individuals who have enough assets as to obviate motivation to apply for financial support. The study also focuses on symptom trajectories over a seven month period. This window was chosen in order to study medium-term change following a major stressful event, and so findings may differ when change is assessed over periods of longer duration. Finally, the study attends to variation in individuals who have all lost jobs, but does not include comparisons to individuals who remain employed, and so can make no claims concerning the causal effects of job loss itself.

Implications

These findings have implications for basic nosology as well as for studies of risk and protective mechanisms. In this and other recent studies, a general internalizing factor accounts for substantial variance in measures of mood and anxiety disorders, in terms of both contemporaneous comorbidity and dynamic changes in symptoms over time. As a result, studies using only measures of depression or anxiety are likely to conflate effects related to this general factor with effects involving variance unique to that specific symptom set. Attention to both general and unique components of these disorders may be necessary to advance our understanding of etiology, and is likely to be important for both prevention and treatment trials. In addition, these findings reinforce the importance of research to determine whether risk and protective mechanisms vary in their effects on both the more general internalizing factor as compared to more diagnosis-specific factors. Tests of differential causes of etiology, course, and resolution are necessary to understand the mechanisms underlying the common/unique distinctions found here.

It will be important to explore whether these findings generalize to individuals in other contexts. The depressive and anxiogenic effects of other severe life events are well established but variation in effects across different stressful contexts has been studied infrequently. Although Kendler et al (2003) provide some evidence that events can be sorted in terms of more general characteristics such as loss, humiliation, or danger, many severe events are likely to involve complex combinations of these factors, making it more challenging to parse the effects of different types of events. A number of investigators have also suggested that a specific type of event, such as job loss, may lead to very different sequelae for different individuals (Brown & Harris, 1978). Some individuals such as single parents may face substantial economic threats, while others such as part-time workers who only supplement family incomes will face much less economic disadvantage, for example. This suggests that future studies would benefit from studying variation within as well as across events in terms of characteristics such as loss and danger or other forms of threat. In addition, threat may vary depending on the actual or perceived controllability of the event (Brown & Harris, 1978). The sequelae of job loss are likely more controllable than events such as the death of a loved one, although even this may vary depending on employment opportunities. Based on Kendler et al's findings, we speculate that events involving a broader range of threats would increase the likelihood of comorbid depressive and anxious response. As a result, general internalizing may reflect a general response that is common across many forms of stressors, while more unique depressive or anxiety responses may be shaped by exposure to stressors that are more limited to particular components such as loss or danger.

Finally, it will be essential to study the specific risk and protective mechanisms that combine both contextual and individual differences factors to understand how these operate in concert to increase risk for both general internalizing and symptom-specific outcomes. This paper is part of a larger effort to study how personality factors, history of depression, and genetic variation interact with variation in exposure to stressors to identify constellations of risk for depression, and anxiety, both unique and comorbid, with future analyses planned to study these more complex models.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01 MH073712 awarded to George W. Howe. We wish to acknowledge the vital support of Thomas Wendell and Julie Ellen Squire of the Maryland Department of Labor, Licensing and Review. We also thank Amy Whitesel and Chris Nettles for their contributions to the study, and the members of the Prevention Science and Methodology Group for their thoughts and comments on early versions of this work.

Footnotes

1. MPLUS program code specifying these models is available from the first author. Other model parameterizations are possible, including a higher-order growth model of an internalizing latent variable measured at each wave. We were however unable to fit such a model due to cross-wave correlation estimates among the latent variables that approached or exceeded 1. In addition, such models do not allow for the separation of growth variance into common and unique components.

2. We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this possibility.

References

- Beesdo-Baum K, Höfler M, Gloster AT, Klotsche J, Lieb R, Beauducel A, Wittchen HU. The structure of common mental disorders: a replication study in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. International Journal Of Methods In Psychiatric Research. 2009;18(4):204–220. doi: 10.1002/mpr.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behar E, Alcaine O, Zuellig AR, Borkovec TD. Screening for generalized anxiety disorder using the Penn State Worry Questionnaire: A receiver operating characteristic analysis. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2003;34(1):25–43. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(03)00004-1. doi:10.1016/S0005-7916(03)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Swartz MS. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: The National Comorbidity Survey. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1994;151(7):979–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth BM, Kirchner JE, Hamilton G, Harrell R, Smith G. Diagnosing depression in the medically ill: Validity of a lay-administered structured diagnostic interview. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1998;32:353–360. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(98)00031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(2):179–192. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.179. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.107.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckby JA, Cotton SM, Cosgrave EM, Killackey EJ, Yung AR. A factor analytic investigation of the Tripartite model of affect in a clinical sample of young Australians. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:79–79. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-8-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris TO, editors. Social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. Tavistock; London: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Carter MM, Sbrocco T, Miller O, Jr., Suchday S, Lewis EL, Freedman REK. Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire: Differences between African-American and White-American college students. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2005;19(8):827–843. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.11.001. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen FF, West SG, Sousa KH. A Comparison of bifactor and second-order models of quality of life. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2006;41(2):189–225. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4102_5. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr4102_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100(3):316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Peeke LG, Martin JM, Truglio R, Seroczynski AD. A longitudinal look at the relation between depression and anxiety in children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66(3):451–460. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.451. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.66.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole JC, Rabin AS, Smith TL, Kaufman AS. Development and Validation of a Rasch-Derived CES-D Short Form. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:360–372. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.4.360. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.16.4.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson JR, Miner CM, De Veaugh-Geiss J, Tupler LA, Colket JT, Potts NLS. The Brief social phobia scale: A Psychometric evaluation. Psychological Medicine. 1997;27:161–166. doi: 10.1017/s0033291796004217. doi:10.1017/S0033291796004217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Affective style and affective disorders: perspectives from affective neuroscience. Cognition and Emotion. 1998;12:307–330. [Google Scholar]

- Dew MA, Penkower L, Bromet EJ. Effects of unemployment on mental health in the contemporary family. Behavior Modification. 1991;15(4):501–544. doi: 10.1177/01454455910154004. doi: 10.1177/01454455910154004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Mennin DS, Heimberg RG, Turk CL. Using the Penn State Worry Questionnaire to identify individuals with generalized anxiety disorder: A receiver operating characteristic analysis. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2003;34(3–4):283–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2003.09.001. doi:10.1016/j.jbtep.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filho AS, Hetem LAB, Ferrari MCF, Trzesniak C, Martín-Santos R, Borduqui T, Crippa JAS. Social anxiety disorder: What are we losing with the current diagnostic criteria? Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2010 Mar;121(3):216–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01459.x. 2010. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis MM, Haaga DAF, Ford GT. Normative values for the Beck Anxiety Inventory, Fear Questionnaire, Penn State Worry Questionnaire, and Social Phobia and Anxiety Inventory. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7(4):450–455. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.450. [Google Scholar]

- Ginexi EM, Howe GW, Caplan RD. Depression and control beliefs in relation to reemployment: What are the directions of effect? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2000;5:323–336. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambrick JP, Rodebaugh TL, Balsis S, Woods CM, Mendez JL, Heimberg RG. Cross-ethnic measurement equivalence of measures of depression, social anxiety, and worry. Assessment. 2010;17(2):155–171. doi: 10.1177/1073191109350158. doi: 10.1177/1073191109350158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Drabant EM, Munoz KE, Kolachana BS, Mattay VS, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. A susceptibility gene for affective disorders and the response of the human amygdala. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:146–152. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe GW. Studying the dynamics of problem behavior across multiple time scales: Prospects and challenges. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2004;32(6):673–678. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000047215.55438.0a. doi: 10.1023/B:JACP.0000047215.55438.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe GW, Levy ML, Caplan RD. Job Loss and Depressive Symptoms in Couples: Common Stressors, Stress Transmission, or Relationship Disruption? Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(4):639–650. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.639. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsten J, Hartman CA, Smit JH, Zitman FG, Beekman ATF, Cuijpers P, van der Does AJW, Ormel J, Nolen WA, Penninx BWJH. Psychiatric history and subthreshold symptoms as predictors of occurrence of depressive or anxiety disorder within 2 years. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;198:206–212. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman MA, Vermani M, Jacobs L, Marcus M, Kong B, Lessard S, Galarraga W, Struzik L, Gendron A. Quetiapine as an adjunctive pharmacotherapy for the treatment of non-remitting generalized anxiety disorder: A flexible-dose, open-label pilot trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22(8):1480–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.03.002. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MC, Neale MC, Kendler KS. Association of different adverse life events with distinct patterns of depressive symptoms. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(10):1521–1529. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091564. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06091564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Hettema JM, Butera F, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of Major Depression and Generalized Anxiety. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(8):789–796. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.789. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Stressful life events and major depression: risk period, long-term contextual threat, and diagnostic specificity. The Journal Of Nervous And Mental Disease. 1998;186(11):661–669. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199811000-00001. doi:10.1097/00005053-199811000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Zhao S. Overview of descriptive epidemiology of mental disorders. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, editors. Handbook of sociology of mental health. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, Netherlands: 1999. pp. 127–150. [Google Scholar]

- Klenk MM, Strauman TJ, Higgins ET. Regulatory focus and anxiety: A self-regulatory model of GAD-depression comorbidity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;50(7):935–943. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.12.003. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Silva PA. The structure and stability of common mental disorders (DSM-III-R): A longitudinal-epidemiological study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(2):216–227. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.2.216. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.107.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Finger MS. Using item response theory to understand comorbidity among anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13(1):140–151. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.13.1.140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MD, Granic I. Emotion, development, and self-organization: dynamic systems approaches to emotional development. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2000. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511527883. [Google Scholar]

- Mazure CM. Life stressors as risk factors for depression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1998;5:291–313. [Google Scholar]

- McFadyen RG. Attitudes toward the unemployed. Human Relations. 1998;51:179–199. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1990;28:487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Fogler JM, Wolf EJ, Kaloupek DG, Keane TM. The internalizing and externalizing structure of psychiatric comorbidity in combat veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21(1):58–65. doi: 10.1002/jts.20303. doi: 10.1002/jts.20303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Harkness KJ. Life stress, the “kindling” hypothesis, and the recurrence of depression: Considerations from a life stress perspective. Psychological Review. 2005;112:417–445. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.2.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]