The diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer bring psychosocial consequences for many patients (Glanz & Lerman, 1992; Moyer & Salovey, 1996), ranging from mild distress to diagnosable mood and anxiety disorders (Antoni, 2003; Holland, 1998). Most women diagnosed with breast cancer experience heightened distress (e.g., Boehmke & Brown, 2005), and a subset of breast cancer patients experience significant levels of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic symptoms (e.g., intrusive thoughts, hyper-arousal) or adjustment disorder symptoms that make successful coping with cancer-related stressors more difficult (e.g., Khan et al., 2012; Mehnert & Koch, 2007). According to Lazarus and Folkmans’ Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), adaptive coping skills can be learned. Consistent with this model, interventions that include coping skills and stress management training for cancer patients have been found to increase positive coping and decrease symptoms (e.g., Andersen et al., 2004; Antoni et al., 2001; Cunningham et al., 1993; Cunningham & Tocco, 1989; Telch & Telch, 1986; Yates et al., 2005). Such interventions not only help patients learn new skills to cope with their current stressors, but also serve to increase coping self-efficacy (i.e., confidence in the ability to cope with cancer), which can empower patients to face the future with less anxiety (Bandura, 1991). Indeed coping self-efficacy has been found to be associated with favorable outcomes in cancer-related contexts, including reduced anxiety, depression and improved quality of life (Giese-Davis et al., 1999; Merluzzi & Martinez Sanchez, 1997; Philip et al., 2012).

Antoni et al’s Cognitive Behavioral Stress Management program (CBSM; Antoni et al., 2001) is one intervention for cancer patients that seeks to facilitate stress management by directly addressing patients’ coping skills. Several clinical trials with early stage breast cancer survivors have shown that CBSM participation was associated with decreased incidence of depression; lower reports of anxiety, cancer-related intrusive thoughts, and distress; and improved positive adjustment to cancer (e.g., finding benefit in the cancer experience and positive affect) as compared to treatment-as-usual or attention control conditions (e.g., Antoni, Lechner, et al., 2006; Antoni et al., 2001; McGregor et al., 2004). Further, the effects of CBSM appear to be durable, with women’s distress continuing to decrease for up to 12 months following treatment (Antoni, Wimberly, et al., 2006). CBSM also seems effective in applied clinical settings with cancer patients (e.g., Beatty & Koczwara, 2010).

Despite substantial evidence for the effectiveness of psychological interventions in reducing distress among cancer patients, dissemination of empirically-validated interventions is challenging, and many patients who could benefit from this intervention do not receive it (Ellis et al., 2005; Jacobsen, 2009; Kerner et al., 2005; Stanton, 2006). This gap in the dissemination and implementation of empirically supported interventions is due not only to a lack of therapists trained in delivering psychosocial interventions, but also to the fact that most interventions are delivered in urban clinic- and university-based settings using in-person groups, which can be difficult to access and fit into survivors’ schedules (Institute of Medicine, 2008).

The internet is one way to overcome these logistical and organizational barriers. Patients already turn to the internet for health information (Atienza et al., 2010). A 2011 Pew Report states that the internet is second only to physicians as a significant source of health information for 80% of online users (Fox, 2011). Although web sites exist in abundance for cancer patients, most are not structured interventions. Our literature search revealed only two CBT-based online interventions for cancer patients, one developed by Owen and colleagues (2005) and the other by Beatty and colleagues (2011), both providing structured CBT for distressed cancer patients. The Owen et al study (2005) investigated an intervention that was not modeled on a specific empirically-validated intervention and a small randomized trial of the intervention revealed no differences between the intervention group and a wait-list control condition. The Beatty et al (2011) intervention was modeled on existing self-help materials and appears promising, although to date it has only been evaluated in a small pilot study.

The goal of the present project was to develop an interactive web-based version of a CBSM intervention for breast cancer survivors, the Coping with Cancer Workbook, and evaluate its effectiveness in a randomized waitlist-controlled trial. The intervention was evaluated using a 2 group × 3 time design. It was hypothesized that, controlling for baseline scores on primary and secondary outcomes, those who received immediate access to the workbook would show better outcomes after 10 weeks than those whose access to the workbook was deferred for 10 weeks.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited locally and nationally using print and online resources, email announcements, community organization websites advertising clinical trials, online discussion boards, word of mouth, local support group presentations, and flyers posted in local cancer centers and community organizations. Most of the women (113 of 132) were recruited via email announcement to the Love/Avon Army of Women breast cancer research registry. Recruitment took place between April and July of 2010.

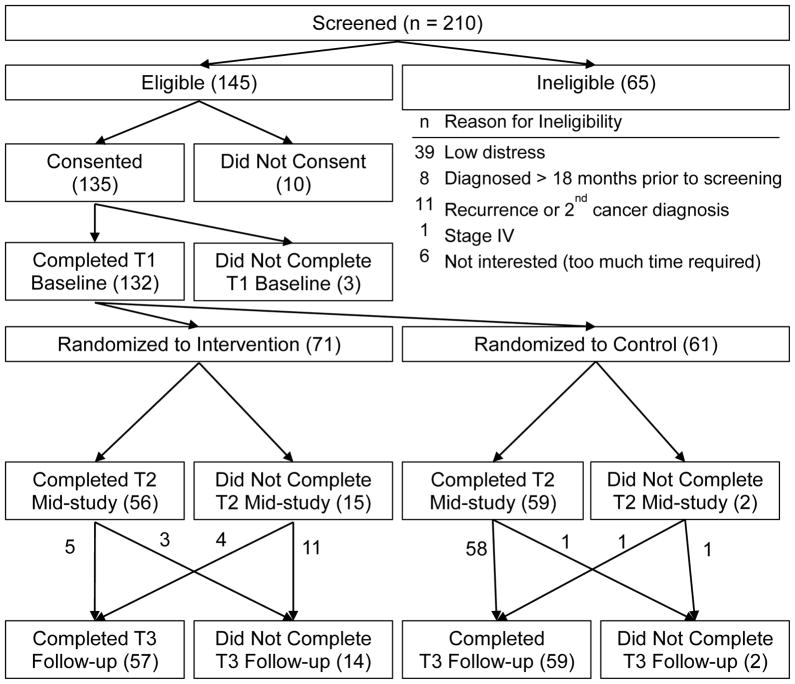

Two hundred and ten women were screened for eligibility (see Figure 1 for the study CONSORT diagram). Eligible participants were English-speaking adult women within 18 months of their diagnosis with Stage 0, I, II, or III breast cancer, reporting at least moderate distress, with reliable access to a phone and the internet. Moderate distress was defined as scoring at least 5 out of 10 on the Distress Thermometer (Hegel et al., 2006), or 6 out of 16 on the 4-item Perceived Stress Scale (corresponding to half a standard deviation above the mean in a community sample of similar aged women; Cohen, 1988), or 7 out of 20 on a 5-item brief adjective checklist similar to the Profile of Mood States which has been used in previous work with CBSM groups for breast cancer survivors. Ineligibility criteria excluded women with a cancer recurrence or concurrent other type of cancer. One hundred thirty-two women completed baseline measures and were randomized. Participants ranged in age from 25 to 73 years, with a mean of 50.9 (SD = 9.9). Nineteen percent endorsed racial or ethnic minority status, 68% were married or partnered, 45% worked full-time, 67% had graduated from college, 94% reported breast cancer-related surgery, 45% had undergone chemotherapy, 49% had undergone radiation, and 20% were currently undergoing chemotherapy or radiation. At diagnosis, 19% were in Stage 0, 38% were in Stage I, 33% were in Stage II, and 11% were in Stage III.

Figure 1.

Study CONSORT diagram.

Procedures

All procedures were approved by a human subjects review board, including a waiver of written consent. Eligible women were emailed a link to the online consent form and a unique user ID and password. Participants read the online consent form and clicked a button labeled “I consent.” Consenting participants continued to the baseline questionnaires. Upon completing the questionnaires, participants were randomized into the intervention or wait-list control condition according to a computerized random number table. Intervention participants were provided immediate access to all chapters of the online Coping with Cancer Workbook. Wait-listed participants were scheduled to receive access to the intervention after completing the 10 week assessment. Between baseline and week 10, all participants received biweekly phone calls from a research assistant to monitor their distress and to keep participants engaged in the study. During the calls, participants completed the Distress Thermometer (Hegel et al., 2006). Acute exacerbations of distress would have prompted further intervention; however, none were encountered. Because intervention participants were also asked about their use of the workbook and offered technical support if necessary, the research assistant was not blind to condition assignment. Dependent variables were not assessed during these calls and no explicit adherence troubleshooting took place.

Ten weeks after completing the baseline assessment, all participants were emailed a link to the week 10 assessment which was completed by 115 (87%). Intervention participants retained access to the workbook, and control participants received access after completing the week 10 assessment. Upon receiving access to the workbook, all participants were encouraged to complete one chapter per week for 10 weeks. At the start of each week of access, participants were sent an email encouraging them to use the next chapter of the workbook, reminding them of the topic to be covered, and asking them to review the exercises that worked well for them during the previous week. Ten weeks after completing the week 10 assessment, all participants were emailed a link to the week 20 assessment completed by 116 (88%) of the participants. Participants were paid $10 for each completed phone call in addition to payments for each completed assessment: $30 for baseline, $30 for the week 10 assessment and $40 for the week 20 assessment.

Measures

Primary outcomes of interest were those which were directly targeted by the intervention, including self-efficacy for coping with cancer, self-efficacy for coping with negative mood, and finding benefit in the cancer experience. Secondary outcomes of interest were variables hypothesized to be indirectly affected by the intervention, including cancer-related post-traumatic symptoms, social well-being, functional well-being, and positive affect.

Self-efficacy for coping with cancer was assessed with the Cancer Behavior Inventory v2.0 (CBI; Merluzzi et al., 2001). Each of 33 items begins with the stem, “I am confident that I can accomplish” and is rated on a 9-point Likert scale ranging from 1, not at all, to 9, totally. Items cover the following domains: activity maintenance/independence, seeking and understanding medical information, stress management, coping with treatment side-effects, accepting cancer and maintaining a positive attitude, affect regulation, and support-seeking. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the full scale was .945. Scores were calculated as a sum of the items, with possible scores ranging from 33–297.

Self-efficacy for coping with negative mood was assessed with the Negative Mood Regulation Scale (NMR; Catanzaro & Mearns, 1990), a 30-item, self-rated scale designed to measure the strength of beliefs in one’s ability to alter negative mood states using a variety of emotion regulation strategies. Statements about one’s beliefs when upset, e.g., “When I’m upset, I believe that I’ll feel okay if I think about more pleasant times,” are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). The scale yields total scores ranging from 30 to 150, with higher scores representing greater belief in one’s ability to alleviate a negative mood. Cronbach’s alpha for the full scale was .902.

Finding benefit in the cancer experience was measured with the Benefit Finding Scale (BFS; Antoni et al., 2001; Carver & Antoni, 2004). Benefit finding refers to survivors’ perceptions of positive contributions to their lives as a result of their cancer diagnosis and treatment experiences. Each of 17 items began with the stem, “Having had breast cancer has,” described a possible benefit, such as “led me to be more accepting of things,” and was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1, not at all, to 5, extremely. Cronbach’s alpha for the full scale was .941. Scores were calculated as a mean of the items, thus ranging from 1–5.

Cancer-related post-traumatic symptoms were assessed with the Revised Impact of Event Scale (IES; Horowitz et al., 1979; Weiss & Marmar, 1997). Twenty-two items cover avoidance, hyper-arousal symptoms, and intrusive thoughts after a traumatic event. Participants were instructed to answer with respect to thoughts about their breast cancer diagnosis over the preceding 7 days. Example items include, “I thought about it when I didn’t mean to” and “I tried not to think about it.” Items were rated on 5-point Likert scales ranging from 0, not at all, to 4, extremely. Cronbach’s alpha for the full scale was .920. Scores were calculated as a mean of the items, thus ranging from 0–4. The IES-R can yield subscale scores for avoidance, intrusions, and hyperarousal, but the only the total score, calculated as a mean of the items, was used in the present study.

Social and functional well-being were assessed with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast (Brady et al., 1997), which consists of thirty-seven items rated on a 5-point Likert scale with response options ranging from 0, not at all, to 4, very much. The items cover five dimensions of quality of life: physical, emotional, social, and functional well-being, as well as other concerns. For example, one item on the 7-item social well-being (SWB) subscale is, “During the past 7 days, I got support from my friends.” An example item from the 7-item functional well-being (FWB) subscale is, “During the past 7 days, I was able to enjoy life.” Cronbach’s alphas for social and functional wellbeing subscales were .833 and .839, respectively. According to convention, ratings are multiplied by seven and subscale scores are calculated as means of constituent items Thus, social and functional well-being scores range from 0–28.

Positive affect over the past week was measured with the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule – Short Form (Mackinnon et al., 1999). Ten items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1, very slightly or not at all, to 5, extremely. Positive affect (PAFF) items included: inspired, alert, excited, enthusiastic, and determined. Cronbach’s alpha for the five items was .844. Scores were calculated as a sum of the items, with possible scores ranging from 1–25.

Satisfaction with the intervention was evaluated with a 28-item questionnaire which asked detailed questions about a variety of aspects of the workbook and study. For the present paper, we examined three single item measures which asked about global satisfaction with the Coping with Cancer Workbook. “I would recommend this workbook to a friend with breast cancer” and “I think this workbook would be a good tool for breast cancer patients” were rated on a 5-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), and “My overall impression of the workbook is…” was rated on 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (terrible) to 5 (wonderful).

Intervention

Modeled after an in-person group intervention originally developed by Antoni and colleagues (Antoni, 2003), the Coping with Cancer Workbook was developed by a team of clinical psychologists and oncology social workers with expertise in CBT interventions in general and the original in-person CBSM intervention in particular, as well as experience in translating face-to-face interventions into self-directed internet interventions. The development process was iterative and included review by content and cultural competency experts in addition to focus groups and usability testing with breast cancer survivors.

The Coping with Cancer Workbook consists of an introduction and ten chapters, including didactic instruction on cognitive and behavioral coping strategies and supporting interactive exercises; relaxation training, including guided imagery and meditation techniques; guided expressive writing exercises; and weekly homework activities to promote integration of new coping skills into daily life. The guided writing exercises were not part of the original face-to-face CBSM intervention and were added in order to offer opportunities for emotional expression and meaning-based coping as are often encouraged in face-to-face groups.

Video and audio elements were used to approximate the personal feel of the original in-person CBSM intervention. In collaboration with a media production expert, five breast cancer survivors were highlighted in video-based vignettes throughout the workbook, each survivor sharing personal insights related to her breast cancer experience, learning new coping skills, and negotiating survivorship. Also via video, a social worker guided users through the workbook, highlighting resources and offering encouragement. These roles were played by actors with scripts written by the content development team based on clinical oncology experience. Finally, an asynchronous discussion board was added to facilitate social support between breast cancer survivors, as one might receive in an in-person support group. An oncology social worker and an oncology nurse (both study research personnel) acted as discussion board moderators.

The Coping with Cancer Workbook was designed to meet diverse learning and accessibility needs. All content was written at or below a sixth-grade reading level, as determined by the Flesch-Kincaid method (Kincaid et al., 1975). Transcripts were provided with all audio and video elements, and online worksheets were made available as printable worksheets for women who prefer writing to typing. All written exercises and journal entries were available by clicking a journal button and a downloadable audio library provided easy access to the relaxation exercises, encouraging participants to rehearse these key skills of the intervention. The journal and the library could be accessed from any page within the workbook. MP3 players pre-loaded with all of the relaxation exercises were sent to each participant for use with the workbook. For more information about the workbook, please see http://www.cancercoping.org.

Participants were given access to the entire workbook, but were encouraged to use one chapter per week. Each chapter followed a consistent structure: 1) Checking In: chapter objectives, a self-assessment of the previous week’s skills, and a 1 to 3 minute relaxation exercise; 2) Skill Building: education on specific CBSM techniques (e.g., identifying stressors, cognitive restructuring, communication skills training), including interactive exercises to promote skill rehearsal and self-reflection; 3) Relaxation: relaxation exercises, guided imagery, or meditation techniques (e.g., progressive muscle relaxation, breath-focused meditation, mindfulness meditation) lasting from 10 to 25 minutes for use in daily practice, 4) Writing: guided self-disclosure exercises (e.g., “describe your strengths and resources in coping with breast cancer”) to facilitate emotional expression and cognitive processing; and 5) The Week Ahead: review of the chapter objectives and suggested homework exercises.

Data Analytic Approach

Hypotheses

Our primary outcome variables were constructs specifically targeted by the CBSM intervention: self-efficacy for coping, self-efficacy for regulating negative mood, and finding benefit in the cancer experience. We hypothesized that at week 10, controlling for baseline scores, as compared to the control group, the intervention group would show higher levels of self-efficacy for coping and regulating negative mood and benefit finding. Moreover, we hypothesized that, as compared to the control group, the intervention group would report higher scores on secondary outcomes that were not directly targeted by the intervention, including social and functional well-being, higher positive affect, and lower levels of cancer-related post-traumatic symptoms. Further, we hypothesized that at week 20, after both groups had used the intervention, group differences would be attenuated in both primary and secondary outcomes.

Sample size determination

The study was powered to detect medium between-groups effects in the primary outcome variables in the context of repeated measures MANOVA. Power analysis conducted using G*Power 3 software (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007) indicated that a sample size of N = 98 with both pretest and posttest data would yield power of .80 to detect a medium effect size (Cohen’s f = .25). Assuming a loss-to-follow-up of 20%, we arrived at a target enrollment of 120 participants.

Baseline differences between groups

We examined whether randomization was successful in producing comparable groups in terms of demographics and baseline characteristics. Chi-square and t-tests revealed no significant differences between the intervention and control groups on any of the demographic, treatment, or outcome variables at baseline.

Relationships between participant characteristics and dependent variables at baseline

Pearson’s product moment and point-biserial correlations were computed as appropriate to examine relationships between the demographic and medical variables on the one hand and baseline scores on the dependent measures on the other. Coefficients are shown in Table 1. Variables found to be significantly related to the dependent variables were included as covariates in hypothesis testing.

Table 1.

Correlations Between Participant Characteristics and Dependent Variables at Baseline

| CBI | BFS | NMR | IES | SWB | FWB | PAFF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | .066 | −.083 | .116 | −.159 | .038 | .141 | .092 |

| Diagnostic Stage | −.037 | .123 | −.155 | .150 | −.096 | −.142 | −.005 |

| Current Treatment | .018 | −.049 | −.088 | .048 | .003 | −.166 | −.127 |

| Cancer-Related Surgery | −.022 | −.051 | −.010 | −.020 | −.062 | −.054 | −.115 |

| Past Chemotherapy | .014 | .057 | −.123 | .077 | −.100 | −.230 | −.051 |

| Past Radiation | .020 | .034 | .079 | −.019 | .016 | .173 | .037 |

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | −.004 | .051 | −.159 | .011 | −.120 | −.149 | −.064 |

| Married or Partnered | .047 | .086 | .134 | −.051 | .179 | .160 | .201 |

| Employed Full-Time | .064 | .171 | .178 | −.080 | .016 | .212 | .161 |

| Graduated College | .160 | −.127 | .127 | −.058 | .119 | .143 | .158 |

Note. CBI, Self-Efficacy for Coping with Cancer; BFS, Benefit Finding NMR, Negative Mood Regulation; IES, Impact of Event Scale; SWB, Social Well-Being; FWB, Functional Well-Being; PAFF, Positive Affect. Bold, italicized coefficients indicate p < .01.

Bold coefficients indicate p < .05.

Retention analyses

Next we examined whether those who completed the 10 week assessment differed from those who did not in terms of demographics and baseline characteristics. A chi-square test revealed that randomized women who did not complete the 10 week assessment were more likely to be in the intervention group than the control group, χ2(1) = 9.32, p = .002, N = 132. Otherwise, there were no significant differences between 10 week completers and non-completers with regard to any of the demographic, background, or baseline outcome variables.

Similar analyses were conducted to examine whether those who completed the 20 week assessment differed from those who did not. Again, there were no significant differences between 20 week completers and non-completers with regard to any of the demographic, background, or baseline outcome variables. However, a chi-square test revealed that women who did not complete the 20 week assessment were more likely to be in the intervention group than the control group, χ2(1) = 8.33, p = .004, N = 132.

Usage data

From the server logs, for each participant we computed the number of unique pages visited, the number of days on which the intervention was visited, and the number of chapters completed. Across conditions, 29% of participants completed all 10 chapters (defined as accessing the final page of each chapter). A chi square test indicated that this percentage did not differ between groups. Participants visited an average 159.8 pages (SD = 93.1) of the 195 unique pages of the workbook (i.e., 82%). Average length of the chapters was 18.2 pages. Participants signed on to the workbook on an average of 13.3 (SD = 8.8) days. Independent groups t-tests indicated that number of pages and number of days did not differ between groups.

Hypothesis testing

We elected to use multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) to test our hypotheses, controlling for baseline scores on the dependent measures and individual difference variables found to be significantly related with the dependent measures at baseline. The between-subjects factor was condition (intervention, control) and the within-subjects factor was time (baseline, 10 week and 20 week). All randomized participants were invited to complete outcome measures and were included in the analyses, without regard to their degree of participation in the intervention. As shown in Figure 1, 84% (111) of randomized participants completed baseline, week 10, and week 20 assessments. Due to the relatively low amount of missing data and the psychosocial nature of the intervention and outcome variables, we did not impute data.

Results

Primary outcomes

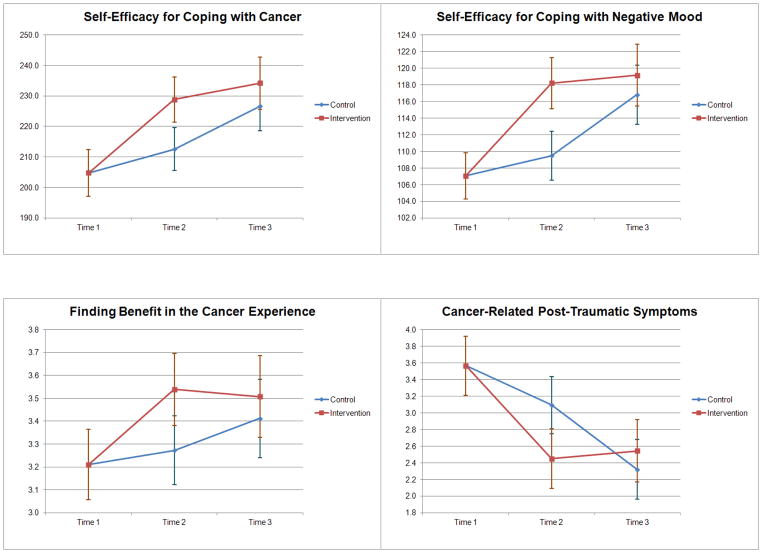

As shown in Table 2, MANCOVA revealed a multivariate main effect for condition, F(3, 98) = 3.04, p = .033, η2 = .085. Examination of the univariate tests indicated that the main effect of condition was significant for self-efficacy for coping with cancer, F(1, 100) = 5.67, p = .019, η2 = .054, and self-efficacy for coping with negative mood, F(1, 100) = 7.58, p = .007, η2 = .070. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed that, controlling for baseline scores and collapsing across week 10 and week 20, self-efficacy for coping with cancer and negative mood scores were significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group (p < .05). Table 3 presents means at baseline, collapsing across condition, and estimated means at weeks 10 and 20, controlling for baseline, by condition. Confidence intervals for estimated means are shown in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Results of MANCOVAs, Controlling for Baseline Scores and Individual Differences

| Wilks’ λ | F | df | p | Partial η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Outcomes: CBI, NMR, BFS | |||||

| Between Subjects Effects | |||||

| intercept | .986 | 0.46 | 3, 98 | .708 | .014 |

| condition | .915 | 3.04 | 3, 98 | .033 | .085 |

| Within Subjects Effects | |||||

| time | .998 | 0.05 | 3, 98 | .985 | .002 |

| time * condition | .934 | 2.31 | 3, 98 | .081 | .066 |

| Secondary Outcomes: IES, SWB, FWB, PAFF | |||||

| Between Subjects Effects | |||||

| intercept | .906 | 2.56 | 4, 98 | .044 | .094 |

| condition | .975 | 0.63 | 4, 98 | .640 | .025 |

| Within Subjects Effects | |||||

| time | .970 | 0.75 | 4, 98 | .342 | .030 |

| time * condition | .898 | 2.77 | 4, 98 | .031 | .102 |

Note. Main effects and interactions are evaluated with the following covariates in the model: past chemotherapy, past radiation, married or partnered, and employed full-time. CBI, Self-Efficacy for Coping with Cancer; BFS, Benefit Finding; NMR, Negative Mood Regulation; IES, Impact of Event Scale; SWB, Social Well-Being; FWB, Functional Well-Being; PAFF, Positive Affect.

Table 3.

Means of Primary and Secondary Outcomes by Condition and Time

| Baseline | Week 10

|

Week 20

|

Condition * Time

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total

|

Control

|

Intervention

|

Control

|

Intervention

|

|||||||||

| M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | F(1, 101) | p | Partial η2 | |

| CBI | 204.8 | 3.9 | 212.5 | 3.5 | 228.8 | 3.7 | 226.7 | 4.1 | 234.2 | 4.3 | – | – | – |

| BFS | 3.2 | 0.1 | 3.3 | 0.1 | 3.5 | 0.1 | 3.4 | 0.1 | 3.5 | 0.1 | – | – | – |

| NMR | 107.1 | 1.4 | 109.5 | 1.5 | 118.2 | 1.5 | 116.8 | 1.8 | 119.2 | 1.9 | – | – | – |

| IES | 3.6 | 0.2 | 3.1 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 2.3 | 0.2 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 10.4 | .002 | .093 |

| SWB | 19.3 | 0.5 | 19.3 | 0.5 | 19.1 | 0.6 | 20.0 | 0.5 | 19.7 | 0.5 | 0.0 | .827 | .000 |

| FWB | 16.3 | 0.5 | 18.0 | 0.5 | 18.8 | 0.5 | 19.1 | 0.6 | 19.5 | 0.6 | 0.2 | .638 | .002 |

| PAFF | 14.2 | 0.4 | 14.6 | 0.5 | 15.7 | 0.5 | 16.1 | 0.5 | 16.4 | 0.6 | 1.3 | .259 | .013 |

Note. All means shown above control for the following covariates: past chemotherapy, past radiation, married or partnered, and employed full-time. Means at Weeks 10 and 20 also control for baseline scores. CBI, Self-Efficacy for Coping with Cancer; BFS, Benefit Finding; NMR, Negative Mood Regulation; IES, Impact of Event Scale; SWB, Social Well-Being; FWB, Functional Well-Being; PAFF, Positive Affect.

Figure 2.

95% confidence intervals for estimated means for the CBI, NMR, BFS, and IES-R as a function of condition and time, controlling for baseline scores.

Secondary outcomes

MANCOVA revealed a multivariate condition by time interaction, F(4, 98) = 2.77, p = .031, η2 = .102. Inspection of the univariate tests, shown in Table 3, indicated that the interaction was significant for cancer-related post-traumatic symptoms, F(1, 108) = 9.66, p = .002, η2 = .088. Means are shown in Table 3, and confidence intervals are shown in Figure 2. Post hoc pairwise comparisons indicated that the conditions differed significantly in level of post-traumatic symptoms at week 10 (p < .05) but not at week 20. The interaction was not significant for any of the other secondary outcomes, and there were no other significant effects.

Global satisfaction with the workbook was high. Means on the three global satisfaction items were high: 4.3 (SD = 0.8) on the overall impression item (5 indicated “wonderful”), 4.4 (SD = 0.8) on the item assessing whether the workbook was a good tool for breast cancer patients (5 indicated strongly agree), and 4.4 (SD = 0.8) on the item assessing whether one would recommend the workbook to a friend with breast cancer (5 indicated strongly agree).

Discussion

The present study found a self-directed online version of an empirically-supported cognitive behavioral stress management intervention for breast cancer patients to be effective in increasing coping self-efficacy, specifically self-efficacy for coping with cancer and self-efficacy for regulating negative mood. Women who were randomly assigned to use the intervention first showed significantly increased self-efficacy at the week 10 assessment, supporting our primary hypothesis and the theoretical underpinnings of the intervention in relation to self-efficacy. Women in the intervention group maintained gains in self-efficacy from week 10 to week 20, while those in the wait-list control group lagged behind until receiving access to the intervention. At week 20, after both groups had used the intervention, we hypothesized that group differences would be attenuated. Although the expected condition by time interaction did not reach significance, support for this hypothesis was found in inspection of the 95% confidence intervals for both measures of self-efficacy, which did not overlap at week 10 but did overlap at week 20. The pattern of results apparent in the graphs suggests that the condition by time interaction did not reach significance because women in the wait-list control group did not entirely catch up to the intervention group at week 20 although they were not significantly different at that time.

Interestingly, unlike the in-person CBSM group intervention, the online adaptation did not appear to affect finding benefit in the cancer experience, for which we found no significant effects or interactions. It is possible that an important determinant of finding benefit in the cancer experience is having the opportunity to engage in emotional expression with other survivors, offering mutual support and the opportunity to process their feelings in a safe supportive environment. Although our online adaptation attempted to provide such an opportunity through a discussion board, it was not frequently used and thus may not have been a reasonable proxy for in-person support.

Among the secondary outcomes, there was a significant condition by time interaction for cancer-related post-traumatic symptoms, which decreased at week 10 in the intervention group but not in the control group. By week 20, the control group evidenced a comparable reduction in post-traumatic symptoms. No significant differences were found in regard to either social or functional well-being, however, and the intervention did not increase positive affect.

The online Coping with Cancer Workbook was focused on teaching a variety of cognitive and behavioral coping strategies and relaxation skills that apply broadly to the lives of women. This approach appeared to have been successful at increasing self-efficacy for both coping with cancer and coping with negative mood, Although we did not measure actual enactment of coping skills, coping self-efficacy is a theoretically important proxy for coping. High coping self-efficacy could decrease stress by changing the appraisal of stressors. Lazarus and Folkman’s theory of stress, appraisal and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Folkman, 2010) states that feeling stressed results from appraising a situation as requiring more personal resources than one possesses. Women who are more confident in their coping abilities may be more likely to appraise situations as manageable, resulting in decreased stress levels and the negative physiological and affective correlates of stress.

The findings from the present Cancer Coping Workbook study are consistent with findings from studies of other web-based psychological interventions, which appear to work about as well as in-person interventions for conditions such as pain, asthma, and improving health behaviors (Cuijpers, 2008; Wantland, 2004). This is not surprising because the Cancer Coping Workbook was based on a face-to-face cognitive behavioral stress management intervention and CBT appears particularly amenable to translation to self-directed web-based formats. Meta-analyses have shown that internet-based CBT interventions are effective overall, with effect sizes similar to those found in meta-analyses of face-to-face treatment (Andersson & Cuijpers, 2009; Spek et al., 2007).

Elements that were added to the online intervention that were not present in the face-to-face version include a discussion board and guided writing exercises. The guided writing exercises were designed to assist the women with expressing and processing their feelings about their cancer experience. As pointed out above, the moderated discussion board was not well utilized by the participants. Given the time limited nature of the study, and the fact that there were never more than 50 women in the intervention arm of the study at any one time, it is perhaps not surprising that the users did not come together to form a support community. There are a number of existing active online communities for breast cancer survivors with memberships that number in the thousands (e.g., www.youngsurvival.org). This experience leads us to question the utility of a discussion board in a time-limited intervention.

In the present study overall attrition was low, but women assigned to the intervention group had significantly higher attrition rates than control group women. We instituted the phone call protocol, in part, to keep the control women engaged in the study and that strategy seems to have been successful. It is unclear why women in the intervention group dropped out at higher rates. One possible explanation is that the control women were eagerly awaiting access to the workbook during weeks 1 through 10, while intervention women who had immediate access could decide right away if the intervention was of interest to them. It is possible, but seems unlikely, that the time requirement of completing the weekly chapter in addition to the phone calls was excessive leading the intervention women to drop out at higher rates; the five phone calls were kept at 10 minutes or shorter and occurred every other week. Because women were screened for elevated levels of stress at baseline, adding one more demand in the face of limited time resources may have been overwhelming to some participants and resulted in their need to discontinue the study. The most common reason cited by participants in both groups who formally withdrew from the study was a lack of time. Completing a chapter of the workbook required about 45 minutes of reading and completing interactive exercises, 20 minutes of writing and another 15 to 30 minutes to complete the relaxation or meditation exercises. Women were also asked to engage in relaxation exercises daily, although this was not tracked. This differential attrition rate is a weakness of the study as it is possible that women who did not find the workbook helpful were the ones who dropped out of the study, making it difficult to interpret the results. Further, as the overall attrition rate was low, we did not impute data to attempt to account for those missing at follow-up.

Another unexpected finding was that use of the workbook was not significantly different between intervention and control women even though the intervention women were contacted by phone five times during the 10 week intervention period and asked about their workbook use. When the control group women were using the workbook, they got weekly email reminders, but no phone calls. Two potential explanations are that either the phone calls did not act as a powerful incentive to use the workbook or the emails were just as powerful. Email does seem to be an effective method of prompting participation in online health interventions (see Fry & Neff, 2009 for a review). Certainly, in a real world setting emails are far less expensive to deploy. If it is true that email reminders are as effective as phone calls in promoting web-based intervention use, this would appear to hold promise for the intervention’s ability to be disseminated, as minimal staffing would be needed to support ongoing participation.

The present study joins an emerging literature supporting the effectiveness of internet based interventions for cancer patients. Internet interventions are gaining popularity because they work and because they decrease many of the barriers to participation in psychosocial treatment: they can be used privately in the home at the convenience of the user and are equally available to urban and rural women. Internet interventions have their own challenges when it comes to dissemination, however. Although the interventions are simple and low cost to deploy, getting them into the hands of patients is difficult and costly. Some countries with national health services promote and support evidence-based internet interventions (e.g., the MoodGym depression intervention in Australia which has been used by at least 30,000 people, Christensen et al., 2004; Christensen et al., 2002). In countries without such a straightforward method of distribution and reimbursement, it remains unclear how broad based dissemination of empirically supported internet interventions will be accomplished.

Limitations of the study include the lack of an active control condition. Further research should compare the workbook to an active treatment or at least an attention control. While we were able to use server logs to track participation in the online intervention, it is unclear how many women practiced the relaxation exercises and for how long. Given that the relaxation training is a key component of the CBSM intervention and the extent to which relaxation influences the psychological and biological outcomes is currently unknown, future web-based CBSM studies must consider ways to track these data. Finally, most of our sample came from the Love/Avon Army of Women research registry and was comprised of women eager to participate in research that might help other women with breast cancer. While certainly not a weakness of the study, it may perhaps limit generalizability of our findings to the general community of breast cancer survivors.

In conclusion, it appears that an internet intervention based on an empirically supported cognitive behavioral stress management intervention is effective for helping breast cancer patients live with more confidence in their ability to cope with stress. Given the increasing demands on healthcare and the fact that breast cancer patients are living longer as survivors, it is critical to find low impact ways to improve their lives. More research is certainly needed to ascertain the long-term effects of such interventions, whether women are able to maintain these positive changes, and whether such an intervention can help prevent the incidence in depression and other disorders in cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by grant number R44 CA106154-02 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) at the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCI.

Our many thanks to all of the people who helped with the development and evaluation of the Coping with Cancer Workbook, including Avon/Love Army of Women; Beth Daranciang, MPH; Linda Eaton, RN, MN, AOCN; Robin Adler, MSW, LICSW; Lynn Dhanak, PhD; Elana Rosenbaum, MS, LICSW; and Jacci Thompson-Dodd, MSW.

References

- Andersen BL, Farrar WB, Golden-Kreutz DM, Glaser R, Emery CF, Crespin TR, Carson WE., 3rd Psychological, behavioral, and immune changes after a psychological intervention: A clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(17):3570–3580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.030. 22/17/3570 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G, Carlbring P, Berger T, Almlov J, Cuijpers P. What Makes Internet Therapy Work? Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2009;1 doi: 10.1080/16506070902916400. 913870867 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH. Stress management and intervention for women with breast cancer. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Lechner SC, Kaxi A, Wimberly SR, Sifre T, Urcuyo KR, Carver CS. How stress management improves quality of life after treatment for breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1143–1152. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Lehman JM, Kilbourn KM, Boyers AE, Culver JL, Alferi SM, Carver CS. Cognitive–behavioral stress management intervention decreases the prevalence of depression and enhances benefit finding among women under treatment for early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2001;20:20–32. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Wimberly SR, Lechner SC, Kazi A, Sifre T, Urcuyo KR, Carver CS. Reduction of cancer-specific thought intrusions and anxiety symptoms with a stress management intervention among women undergoing treatment for breast cancer. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(10):1791–1797. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.10.1791. 163/10/1791 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atienza AA, Hesse BW, Gustafson DH, Croyle RT. E-health research and patient-centered care examining theory, methods, and application. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38(1):85–88. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.10.027. S0749-3797(09)00749-1 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavioral and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:248–257. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty L, Koczwara B. An effectiveness study of a CBT group program for women with breast cancer. Clinical Psychologist. 2010;14(2):45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Beatty L, Koczwara B, Wade T. Cancer coping online: A pilot trial of a self-guided CBT internet intervention for cancer-related distress. Electronic Journal of Applied Psychology. 2011;7(2):17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Boehmke MM, Brown JK. Predictors of symptom distress in women with breast cancer during the first chemotherapy cycle. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal. 2005;15(4):215–227. doi: 10.5737/1181912x154215220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, Bonomi AE, Tulsky DS, Lloyd SR, Shiomoto G. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1997;15(3):974–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Antoni MH. Finding benefit in breast cancer during the year after diagnosis predicts better adjustment 5 to 8 years after diagnosis. Health Psychology. 2004;23(6):595–598. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.595. 2004-20316-005 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catanzaro SJ, Mearns J. Measuring generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation: Initial scale development and implications. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1990;54(3–4):546–563. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF. Delivering interventions for depression by using the internet: randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 2004;328(7434):265. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37945.566632.EEbmj.37945.566632.EE. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Korten A. Web-based cognitive behavior therapy: Analysis of site usage and changes in depression and anxiety scores. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2002;4(1):e3. doi: 10.2196/jmir.4.1.e3. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Andersson G. Internet-administered cognitive behavior therapy for health problems: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31(2):169–177. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9144-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham AJ, Lockwood GA, Edmonds CV. Which cancer patients benefit most from a brief, group, coping skills program? International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1993;23(4):383–398. doi: 10.2190/EQ7N-2UFR-EBHJ-QW4P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham AJ, Tocco EK. A randomized trial of group psychoeducational therapy for cancer patients. Patient Education and Counseling. 1989;14(2):101–114. doi: 10.1016/0738-3991(89)90046-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis P, Robinson P, Ciliska D, Armour T, Brouwers M, O’Brien MA, Raina P. A systematic review of studies evaluating diffusion and dissemination of selected cancer control interventions. Health Psychology. 2005;24(5):488–500. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.5.488. 2005-09850-007 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39(2):175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S. Stress, coping, and hope. Psycho-Oncology. 2010;19(9):901–908. doi: 10.1002/pon.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox S. The social life of health information 2011. 2011 May 12; Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/~/media/Files/Reports/2011/PIP_Social_Life_of_Health_Info.pdf.

- Fry JP, Neff RA. Periodic Prompts and Reminders in Health Promotion and Health Behavior Interventions: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2009;11(2):e16. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giese-Davis J, Koopman C, Butler LD, Classen C, Morrow GR, Spiegel D. Self-efficacy with emotions predicts higher quality of life in primary breast cancer patients. Self-efficacy and Cancer: Theory, Assessment and Treatment; Symposium conducted at the Annual Meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine; San Diego, CA. 1999. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Lerman C. Psychosocial impact of breast cancer: A critical review. ANNALS of Behavioral Medicine. 1992;14(3):204–212. [Google Scholar]

- Hegel MT, Moore CP, Collins ED, Kearing S, Gillock KL, Riggs RL, Ahles TA. Distress, psychiatric syndromes, and impairment of function in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer. 2006;107(12):2924–2931. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland JC. Psycho-Oncology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1979;41(3):209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler NE, Page AEK, editors. Institute of Medicine (IOM) Cancer care for the whole patient: Meeting psychosocial health needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen PB. Promoting evidence-based psychosocial care for cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18(1):6–13. doi: 10.1002/pon.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerner J, Rimer B, Emmons K. Introduction to the special section on dissemination: dissemination research and research dissemination: how can we close the gap? Health Psychology. 2005;24(5):443–446. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.5.443. 2005-09850-001 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan F, Amatya B, Pallant JF, Rajapaksa I. Factors associated with long-term functional outcomes and psychological sequelae in women after breast cancer. Breast. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.01.013. S0960-9776(12)00019-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E, Han JY, Moon TJ, Shaw B, Shah DV, McTavish FM, Gustafson DH. The process and effect of supportive message expression and reception in online breast cancer support groups. Psycho-Oncology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/pon.1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kincaid JP, et al. Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel (Research Branch Report) National Technical Information Service; Springfield, Virginia: 1975. pp. 8–75. 22151 (AD-A006 655/5GA) [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MA, Golant M, Giese-Davis J, Winzlenberg A, Benjamin H, Humphreys K, Spiegel D. Electronic support groups for breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97(4):920–925. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon A, Jorm AF, Christensen H, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Rodgers B. A short form of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule: Evaluation of factorial validity and invariance across demographic variables in a community sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;27(3):405–416. doi: 10.1016/s0191-8869(98)00251-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor B, Antoni M, Boyers A, Alferi S, Blomberg B, Carver C. Cognitive-behavioral stress management increases benefit-finding and immune function among women with early-stage breast cancer. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;56:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehnert A, Koch U. Prevalence of acute and post-traumatic stress disorder and comorbid mental disorders in breast cancer patients during primary cancer care: A prospective study. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16(3):181–188. doi: 10.1002/pon.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merluzzi TV, Martinez Sanchez MA. Assessment of self-efficacy and coping with cancer: development and validation of the cancer behavior inventory. Health Psychology. 1997;16(2):163–170. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.16.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merluzzi TV, Nairn RC, Hegde K, Martinez Sanchez MA, Dunn L. Self-effiacy for coping with cancer: revision of the Cancer Behavior Inventory version 2.0. Psycho-Oncology. 10(3):206–217. doi: 10.1002/pon.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer A, Salovey P. Psychosocial sequelae of breast cancer and its treatment. ANNALS of Behavioral Medicine. 1996;18(2):110–125. doi: 10.1007/bf02909583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Klapow J, Roth D, Shuster J, Bellis J, Meredith R, Tucker D. Randomized pilot of a self-guided internet coping group for women with early-stage breast cancer. ANNALS of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30(1):54–64. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3001_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip EJ, Merluzzi TV, Zhang Z, Heitzmann CA. Depression and cancer survivorship: importance of coping self-efficacy in post-treatment survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2012 doi: 10.1002/pon.3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklicek I, Riper H, Keyzer J, Pop V. Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37(3):319–328. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706008944. S0033291706008944 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL. Psychosocial concerns and interventions for cancer survivors. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(32):5132–5137. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8775. 24/32/5132 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telch CF, Telch MJ. Group coping skills instruction and supportive group therapy for cancer patients: A comparison of strategies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54(6):802–808. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.54.6.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wantland DJ, Portillo CJ, Holzemer WL, Slaughter R, McGhee EM. The effectiveness of Web-based vs. non-Web-based interventions: A meta-analysis of behavioral change outcomes. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2004;6(4):e40. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.4.e40. v6e40 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D, Marmar C. The Impact of Event Scale-Revised. In: Wilson J, Keane T, editors. Assessing psychological trauma. New York: The Guilford Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Winzelberg AJ, Classen C, Alpers GW, Roberts H, Koopman C, Adams RE, Taylor CB. Evaluation of an internet support group for women with primary breast cancer. Cancer. 2003;97(5):1164–1173. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates P, Aranda S, Hargraves M, Mirolo B, Clavarino A, McLachlan S, Skerman H. Randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention for managing fatigue in women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(25):6027–6036. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.271. 23/25/6027 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]