Abstract

Objective

To compare population versus customized fetal growth norms in identifying neonates at risk for adverse outcomes (APO) associated with small for gestational age (SGA).

Study Design

Secondary analysis of an intrapartum fetal pulse oximetry trial in nulliparous women at term. Birthweight percentiles were calculated using ethnicity- & gender-specific population norms and customized norms (Gardosi).

Results

508 (9.9%) and 584 (11.3%) neonates were SGA by population (SGApop) and customized (SGAcust) norms. SGApop infants were significantly associated with a composite adverse neonatal outcome, neonatal intensive care admission, low fetal oxygen saturation and reduced risk of cesarean delivery; while both SGApop and SGAcust were associated with a 5-minute Apgar score < 4. The ability of customized and population birthweight percentiles in predicting APO was poor (12 out of 14 APOs had AUC <0.6).

Conclusion

In this intrapartum cohort, neither customized nor normalized-population norms adequately identify neonates at risk of APO related to SGA.

Keywords: customized norm, fetal growth, small for gestational age, adverse outcomes

Introduction

Disturbances in fetal growth are associated with increased neonatal and infant morbidities as well as adverse long term health consequences.(1–5) Fetal growth is determined by a combination of genetic, environmental, physiologic and pathologic influences. Traditionally, evaluation of fetal growth has been accomplished by comparing fetal or neonatal weight to population based norms. (6, 7) These population norms are usually derived from either heterogeneous or highly-selected patient cohorts that included abnormally grown fetuses (whether large or small), and fail to account for individual variability. Relying on these norms can lead to misclassification of growth e.g. pathologic fetal growth restriction versus constitutionally small but otherwise healthy fetus. (8,9)

In order to circumvent these limitations with population-based standards, a number of customized norms have been developed. Customized norms model the optimal fetal growth in an uncomplicated pregnancy by accounting for individual variables that are known to affect growth. They allow the measurement of deviation from an ideal fetal growth potential rather than deviation from an expected norm for a population, and thus are thought to be a better predictor of adverse perinatal outcomes. (9) One of the more widely used models is that of Gardosi et al. (10–13) Using large datasets of normal pregnancies, Gardosi and colleagues developed a model that determines the optimal growth of each fetus using specific maternal and fetal characteristics. This model has been shown to better detect disturbances in fetal growth. (8–11) The association between abnormal fetal growth by customized growth potential and adverse perinatal outcomes has been validated in various studies from different countries (UK, Sweden, New Zealand, Australia, and others). (9, 13) Recently, using a large US cohort, Gardosi et al determined the coefficients for the customized growth model for the US population and then internally validated, in the same database used to develop the coefficients, the association between small for gestational age (SGA) status by the customized model and adverse perinatal and neonatal outcomes (APO). (12, 14)

The ability of the Gardosi model for the US population to predict APO associated with SGA has not been validated in a patient cohort that is independent from the one from which the model was derived. Additionally its usefulness in an intrapartum setting has not been verified. Therefore, our aims in this study are to test our hypotheses that smallness for gestational age is associated with APO and that a customized fetal growth norm compared with a normalized-population standard better identifies these APOs; and consequently externally validate the Gardosi model for the US population using an intrapartum cohort.

Materials & Methods

Study Design

This was a secondary analysis of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network multicenter randomized trial of intrapartum fetal pulse oximetry conducted between May 2002 and February 2005 in 14 US centers. (15) Nulliparous women who had a singleton, cephalic, living fetus at or beyond 36 weeks of gestation, and who were in early labor (cervical dilatation between 2 cm and 6 cm) were randomly assigned to either open or masked fetal pulse oximetry. Further details of the methodology of the study have been described elsewhere. (15) All women enrolled in the trial (n=5341) were eligible for inclusion in the secondary analysis except those women with missing information needed to determine the customized fetal growth, and pregnancies complicated by major congenital malformations (n=193). This study was deemed exempt from institutional review board review since the data and samples were de-identified before the analysis was performed.

Growth Centile Calculations

Centile birthweight was determined for each individual pregnancy using ethnicity- and gender-specific population (pop) norm, (6) and from a customized (cust) growth standard developed by Gardosi et al.(12,13) The Gardosi customized growth model generates optimal growth curves for individual pregnancies by taking into account maternal and fetal characteristics: maternal weight (kg) and height (cm) at entry to care or pre-pregnancy, ethnicity/race, parity (any birth after 20 weeks), and infant gender. (10,11) The actual birthweight was compared with the optimal weight, and a measure of the percentage of optimal growth was calculated using GROW (Gestation Related Optimal Weight) at www.gestation.net. (13) Small for gestational age (SGA) was defined as ≤10th percentile by either population (SGApop) or customized (SGAcust) method.

Outcomes

As this is a study in an intrapartum low risk cohort, our primary outcome was a composite neonatal outcome that included neonatal death, intrapartum stillbirth, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission > 48 hours, 5-minute Apgar score < 4, umbilical artery blood pH < 7.0, seizures, or intubation in the delivery room. Secondary outcomes analyzed included components of the composite outcome as well as low fetal oxygen saturation defined as fetal oxygen saturation less than 30% for at least 2 consecutive minutes. Death, intrapartum stillbirth, NICU admission > 48 hours, seizures and intubation in the delivery room were not frequent enough to warrant separate analysis as secondary outcomes. We also analyzed NICU admission, cesarean delivery and placental abruption. Details about these selected outcomes are described elsewhere. (15)

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (www.r-project.org). In the original trial, the fetal pulse oximeter did not influence outcomes; therefore, the two study groups (oximeter and control) were combined into one cohort for the current analysis. The odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the various APOs were calculated for SGAcust and SGApop. The concordance between presence or absence of SGA and presence or absence of APO was calculated for each norm and APO. For each APO and norm, a case was concordant when SGA by that norm and that particular APO were both present or both absent. Concordance was compared between the population and customized norms for each APO using McNemar test. (16)

Since the continuous values of the population norms were not available to us, we used the following approximation approach. After an Arc-Tan based transformation of birth weights (ArcTan((weight/1000)2)*2/π), we calculated the corresponding continuous values of the population norms using a simple approximation method based on the linear connection of the 3rd, 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles provided by Alexander et al. (6) in the different races, infant genders and gestational age groups. The ability of the customized and generated population birthweight centiles to predict APOs was then compared using the receiver operating characteristics curve (ROC) and the area under the curve (AUC, or c-statistic). For this study, since we did not assume any prior knowledge of the association, we did not specify the association direction (positive or negative) between an adverse outcome and SGA but rather used a two-sided approach. To be predictive of an event, the AUC must be at least 0.5 and the 95% CI must not cross 0.5. The population and customized AUC’s for an individual outcome were then compared using a nonparametric statistical method for comparing AUC’s. (17) Two-sided p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant and no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Results

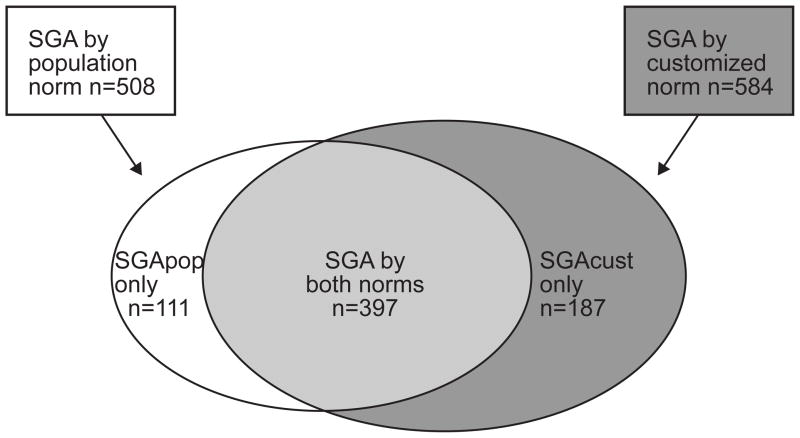

5148 women and their children were included in the analysis. Five hundred eight (9.9%) neonates were SGA by population norms (SGApop) and 584 (11.3%) were SGA by customized norms (SGAcust) (Figure 1). Three hundred and ninety seven neonates were SGA by both methods, 111 were SGA by population centiles only (i.e. not SGA by customized), and 187 were SGA by customized norms only (i.e. not SGA by population) (Figure 1). The baseline maternal and fetal characteristics of the SGApop and SGAcust neonates, compared with those of neonates not SGA by either norm, are summarized in Table 1. Only 27 (3.9%) infants born SGA by either norm (n=695) developed the primary neonatal outcome.

Figure 1.

distribution of neonates classified as small for gestational age (SGA) by the population (SGApop, n=508) and the customized methods (SGAcust, n=584). The diagram also shows the subgroups that are SGA by both methods (n=397) and SGA by population or customized norms only (SGApop only, n=111 and SGAcust only, n=187)

Table 1.

Maternal and fetal characteristics of SGA neonates by population or customized standards, and those not SGA by either.

| Variable | SGA by population (N=508) | SGA by customized (N=584) | Not SGA by either method (N=4453) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Maternal age (years) | 23.2 (5.5) | 23.3 (5.5) | 23.6 (5.5) |

|

| |||

| BMI (at entry to care) (kg/m2) | 24.5 (5.9) | 27.4 (7.3) | 25.4 (6.0) |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 168 (33.1) | 238 (40.7) | 1345 (30.2) |

| African American | 260 (51.2) | 289 (49.5) | 2374 (53.3) |

| Hispanic | 65 (12.8) | 50 (8.6) | 641 (14.4) |

| Other | 15 (2.9) | 7 (1.2) | 93 (2.1) |

|

| |||

| GA at delivery (weeks) | 39.4 (1.2) | 39.9 (1.4) | 39.8 (1.3) |

|

| |||

| Parity | |||

| 1 | 508 (100) | 584 (100) | 4453 (100) |

| >1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

|

| |||

| Birth weight (grams) | 2632.5 (253.5) | 2728.6 (311.5) | 3463.0 (403.2) |

|

| |||

| Male gender | 271 (53.4) | 305 (52.2) | 2333 (52.4) |

Data are reported as mean (SD), or n (%)

SGA = small for gestational age, BMI = body mass index, GA = gestational age

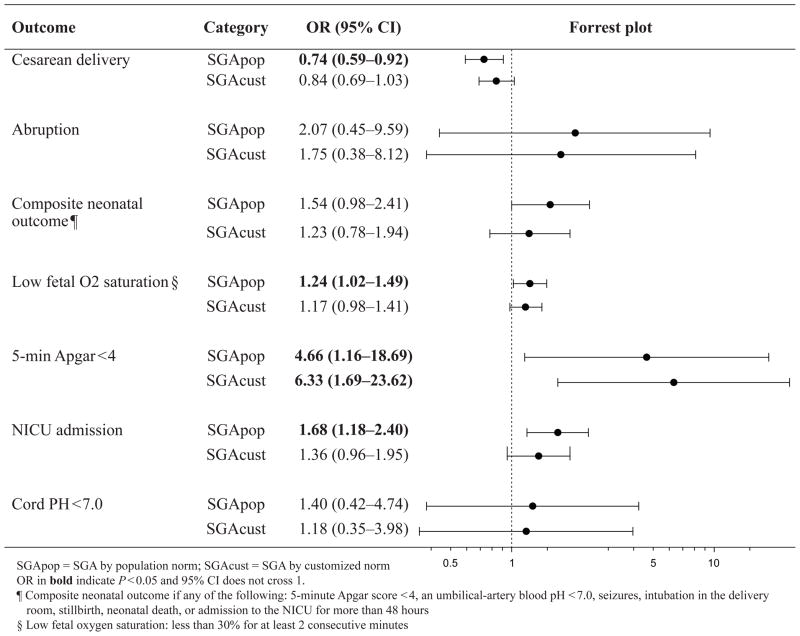

The associations between SGApop and SGAcust with APO and the incidence of APO in the different groups are summarized in Figure 2. Only SGApop was associated with a significant increase in the composite neonatal outcome (OR 1.59, 95%CI 1.02 – 2.48, p=0.038), NICU admission (OR 1.71, 95%CI 1.20 – 2.43; p =0.002) and low fetal oxygen saturation (OR 1.25, 95%CI 1.03 – 1.51; p=0.024); while both SGApop and SGAcust were significantly associated with a 5-minute Apgar score < 4 (for SGApop, OR 4.59, 95%CI 1.14 – 18.4, p=0.018; for SGAcust, OR 6.29, 95%CI 1.68 – 23.5, p=0.002). Neither SGAcust nor SGApop was associated with placental abruption or cord pH < 7.0. The odds of CD were reduced in both groups, but was only significant in the SGApop group (OR 0.75, 95%CI 0.60 – 0.93; p=0.010).

Figure 2.

Odds and incidence of adverse perinatal and neonatal outcomes in SGA neonates by population or customized norms categories compared with those not SGA.

The proportions of agreement between the APOs and either SGApop or SGAcust ranged between 66% and 90% (Table 2). SGApop had significantly higher proportions of agreement (i.e. higher proportions of correct associations between SGA status and the outcome, as well as non-SGA status and the absence of the outcome) than SGAcust for all outcomes except for CD for which the difference in agreement was not statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion of agreement between SGA status defined as < 10th percentile and outcome

| SGApop % | SGAcust % | P * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Composite neonatal outcome ¶ | 87.9 | 86.3 | <0.0001 |

| Low fetal O2 saturation § | 66.4 | 65.6 | 0.021 |

| 5-min Apgar < 4 | 90.1 | 88.6 | <0.0001 |

| NICU admission | 86.6 | 85.1 | <0.0001 |

| Cord blood pH < 7.0 | 89.8 | 88.3 | <0.0001 |

| Cesarean delivery | 67.6 | 67.2 | 0.247 |

| Placental abruption | 90.0 | 88.5 | <0.0001 |

SGApop = SGA by population norm; SGAcust = SGA by customized norm

P using McNemar test for difference to test the agreement between SGApop & SGAcust for the outcome

Composite neonatal outcome if any of the following: 5-minute Apgar score < 4, an umbilical-artery blood pH <7.0, seizures, intubation in the delivery room, stillbirth, neonatal death, or admission to the NICU for more than 48 hour

Low fetal oxygen saturation: less than 30% for at least 2 consecutive minutes

Table 3 summarizes the AUC (and 95 % CI) of the ROC curve for prediction of APO by population and customized norms. In general, the ability to predict adverse outcomes was poor as 12 out of the 14 ROC’s had AUC’s less than 0.6. No significant differences between methods were noted for any of the AUCs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Area under (AUC) the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve for prediction of adverse perinatal and neonatal outcomes by population and customized norms

| Population AUC¥ (95% CI) | Customized AUC (95% CI) | P* | Interpretation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite neonatal outcome ¶ | 0.56 (0.52–0.61) | 0.56 (0.51–0.60) | 0.671 | Both predictive, not statistically different |

| Low fetal O2 saturation § | 0.49 (0.48–0.51) | 0.48 (0.47–0.50) | 0.079 | Neither predictive |

| 5-min Apgar < 4 | 0.73 (0.58–0.88) | 0.69 (0.53–0.86) | 0.488 | Both predictive, not statistically different |

| NICU admission | 0.54 (0.50–0.58) | 0.55 (0.52–0.59) | 0.329 | Both predictive, not statistically different |

| Cord blood pH < 7.0 | 0.51 (0.40–0.62) | 0.43 (0.32–0.53) | 0.042 | Neither predictive |

| Cesarean delivery | 0.54 (0.52–0.56) | 0.53 (0.51–0.55) | 0.280 | Both predictive, not statistically different |

| Placental abruption | 0.51 (0.32–0.70) | 0.57 (0.39–0.75) | 0.401 | Neither predictive |

P for two-sided, pair-wise ROC comparison. (AUC with CI crossing 0.5 was not considered for the comparison). Bold for AUC > 0.5 and 95% CI does not cross 0.5

Composite neonatal outcome if any of the following: 5-minute Apgar score < 4, an umbilical-artery blood pH <7.0, seizures, intubation in the delivery room, stillbirth, neonatal death, or admission to the NICU for more than 48 hour

Low fetal oxygen saturation: less than 30% for at least 2 consecutive minutes

After an Arc-Tan based transformation of birth weights (ArcTan((weight/1000)2)*2/π), we calculated the corresponding continuous values of the population norms using a simple approximation method based on the linear connection of the 3rd, 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles provided by Alexander et al. (6) in the different races, infant genders and gestational age groups.

Discussion

In an intrapartum cohort, neither customized nor normalized population norms identify neonates at risk of adverse outcomes related to smallness for gestational age. However, there was an association between SGA and a composite adverse neonatal outcome when using a population-based approach, but not when using a customized approach.

Our study is novel in that we used two approaches in analyzing the data: first, we analyzed the association between neonates born ≤10th percentile and APO, and then we approximated the continuous values of the population percentiles and compared the 2 norms using ROC curves, which has not been done in the prior validation studies. It was also unique as we attempted to externally validate the Gardosi customized model for the US population in an intrapartum setting. Additional strengths of our study include the use of the same cohort of patients to compare customized and population norms. This allowed us to control for differences in potential confounders when using different cohorts, such as pregnancy dating bias which is especially important. (18) In addition, the outcomes have been accurately ascertained in the primary study.

This study, however, is limited by its sample size which is relatively smaller compared with the one used to develop the coefficients for the US population (12), and which did not allow us to compare outcomes between neonates who were SGA for one but not the other norm, however that does not negate our since our sample is derived from a cohort of patients deemed stable for vaginal delivery. In addition, this was basically a cohort of term nulliparous women with a normal fetal heart rate tracing, enrolled in a multicenter trial and delivering at university hospitals and therefore with expected low rate of adverse events related to SGA. In fact the primary neonatal outcome developed only in 27 infants out of 695 born SGA by either norm (3.9%). This is not surprising as fetuses with suspected significant growth restriction and pregnancy with evolving obstetrical complications were excluded or may have been delivered by cesarean before labor for fetal or maternal indications. Additional limitation is that women were being enrolled at the time of delivery, and so pre-pregnancy weight may not be the most accurate and not as well collected. Because only nulliparous women were included, the parity component of the customized model was not applicable in this cohort. Moreover, it is important to note that the population norm that we used is not typically used in clinical practice or most studies. The typical norms either do not take into account any variables other than gestational age, or merely add either infant gender or ethnicity. By including both in the norm we used, and by nullifying the contribution of the parity variable, we limited our ability to detect differences in performance between the 2 norms. This is different from prior studies that compared the customized model to the more often used population norm which is not adjusted for gender and ethnicity.

Our findings should not be used to dismiss the Gardosi model for the US population, as the limitations of this study may explain some of the apparent discrepancy between our results and those from other studies that demonstrated that SGAcust is superior than SGApop in association with antepartum, intrapartum and neonatal complication. (9, 19–25) The discrepancy regarding stillbirth with the internal validation of the US model (14) may be explained by the fact that our data was limited only to intrapartum stillbirth. Moreover, 32.0 % (187 out of 584; Figure 1) of neonates in our cohort who were SGA by customized standards were not classified as SGA by population norms, and these neonates have been reported in previous studies to have higher risk of adverse outcomes. (9, 14) Conversely, only 21.8 % (111 out of 508; Figure 1) of neonates determined to be SGA by population standards were not detected as SGA by the customized approach, and these were found in prior studies not to be associated with increased rates of neonatal complications. (9, 14)

In summary, a customized approach for fetal growth assessment did not perform better than a normalized population approach that adjusts for ethnicity and infant gender, and neither approach was adequate in predicting infants at risk of adverse outcomes related to SGA in our cohort of low risk women. Further studies are necessary to determine if using ultrasound based customized fetal weights as a standard measure improves neonatal and infant health outcomes, and to investigate the utility of the customized model in predicting the long term outcomes associated with growth restriction.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) [HD21410, HD27860, HD27869, HD27915, HD27917, HD34116, HD34136, HD34208, HD40485, HD40500, HD40512, HD40544, HD40545, HD40560, and HD36801] and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NICHD or NIH.

The authors wish to acknowledge Network members who contributed as follows: George Saade, M.D. (manuscript review), Elizabeth Thom, Ph.D. and Steven Weiner, M.S. (protocol/data management and statistical analysis), Allison T. Northen, M.S.N., R.N. (protocol development and coordination between clinical research centers), and Kenneth, J. Leveno, M.D. (protocol development and oversight).

Abbreviations

- SGA

small for gestational age

- APO

adverse perinatal and neonatal outcomes

- pop

population

- cust

customized

- ROC

receiver operating characteristics curve

- AUC

area under the curve

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- BMI

body mass index

- NICU

neonatal intensive care unit

- GA

gestational age

- CD

cesarean delivery

In addition to the authors, other members of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network are as follows:

University of Alabama at Birmingham — A. Northen, K. Bailey, J. Grant, S. Tate, T. Hill-Webb

Brown University — M. Carpenter, J. Tillinghast, D. Allard, P. Breault, N. Connolly, J. Silva

Case Western Reserve University-MetroHealth Medical Center — C. Milluzzi, C. Heggie, H. Ehrenberg, B. Stetzer

Columbia University — V. Pemberton, S. Bousleiman, H. Husami, V. Carmona, S. South

Drexel University — M. Talucci, M. Pollock, M. Sherman, C. Tocci, E. Selzer

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill — S. Brody, J. Granados, K. Clark, J. Mitchell, K. Dorman

Northwestern University — G. Mallett, N. Cengic, M. Huntley, T. Triplett

The Ohio State University — F. Johnson, S. Fyffe, M. Landon

University of Pittsburgh — M. Cotroneo, M. Luce, H. Birkland, M. Bickus, L. Creswell-Hartman

The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston — M. Day, F. Ortiz, B. Figueroa, S. Shaunfield, M. Messer

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center — K. Leveno, J. Gold, L. Moseley

University of Utah — K. Anderson (University of Utah Health Sciences Center), B. Oshiro (McKay-Dee Hospital), F. Porter (Intermountain Healthcare), K. Jolley (Utah Valley Regional Medical Center), A. Guzman (McKay-Dee Hospital)

Wake ForestUniversity Health Sciences — M. Swain, J. Chilton, C. Leftwich, W. Davido, K. Johnson

Wayne State University — G. Norman, B. Steffy, C. Sudz, S. Blackwell

The George Washington University Biostatistics Center — E. Thom, S. Weiner, A. Swanson, F. Galbis-Reig, L. Leuchtenburg

Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development — S. Tolivaisa, K. Howell

MFMU Network Steering Committee Chair (University of Texas Medical Center, Galveston, TX) — G. Anderson, M.D.

Footnotes

Disclosure: None of the authors have a conflict of interest

Presentation Information: Presented in part at the Society for Gynecologic Investigation 58th Annual Scientific Meeting in Miami, FL, March 17–19, 2011

References

- 1.McIntire DD, Bloom SL, Casey BM, Leveno KJ. Birth weight in relation to morbidity and mortality among newborn infants. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1234–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904223401603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schoendorf KC, Hogue CJ, Kleinman JC, Rowley D. Mortality among infants of black as compared with white college educated parents. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1522–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199206043262303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kajantie E, Osmond C, Barker DJ, Forsen T, Phillips DI, Eriksson JG. Size at birth as a predictor of mortality in adulthood: a follow-up of 350 000 person-years. Int J epidemiol. 2005;34:655–63. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barker DJ, Osmond C, Forsen TJ, Kajantie E, Eriksson JG. Trajectories of growth among children who have coronary events as adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1802–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozanne SE, Fernandez-Twinn D, Hales CN. Fetal growth and adult dieseases. Semin Perinatol. 2004;28:81–87. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alexander GR, Kogan MD, Himes JH. 1994–1996 U.S. singleton birth weight percentiles for gestational age by race, Hispanic origin, and gender. Matern Child Health J. 1999;3:225–231. doi: 10.1023/a:1022381506823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hadlock FP, Harrist RB, Martinez-Poyer J. In utero analysis of fetal growth: a sonographic weight standard. Radiology. 1991;181:129–33. doi: 10.1148/radiology.181.1.1887021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reeves S, Bernstein IM. Optimal growth modeling. Semin Perinatol. 2008;32:148–153. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardosi J. Customized fetal growth standards: rationale and clinical application. Semin Perinatol. 2004;28:33–40. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardosi J, Chang A, Kalyan B, Sahota D, Symonds EM. Customised antenatal growth charts. Lancet. 1992;339:283–7. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91342-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardosi J, Mongelli M, Wilcox M, Chang A. An adjustable fetal weight standard. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;6:168–174. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1995.06030168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gardosi J, Francis A. A customized standard to assess fetal growth in an American population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:25.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.GROW: Gestation Related Optimal Weight. [Accessed April, 20, 2011];Customised growth chart software versions 5.x-7.x. 2000–2009 Available at: Gestation Network, www.gestation.net.

- 14.Gardosi J, Francis A. Adverse pregnancy outcome and association with small for gestational age birthweight by customized and population-based percentiles. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:28.e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloom SL, Spong CY, Thom E, Varner MW, Rouse DJ, Weininger S, et al. for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Fetal pulse oximetry and cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2195–202. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNemar Q. Note on the Sampling Error of the Difference between Correlated Proportions or Percentages. Psychometrika. 1947;12:153–157. doi: 10.1007/BF02295996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the Areas Under Two or More Correlated Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves: A Nonparametric Approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mongelli M, Wilcox M, Gardosi J. Estimating the date of confinement: Ultrasonographic biometry versus certain menstrual dates. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:278–281. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70408-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Jong CL, Gardosi J, Dekker GA, Colenbrander GJ, van Geijn HP. Application of a customised birthweight standard in the assessment of perinatal outcome in a high risk population. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;105:531–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clausson B, Gardosi J, Francis A, Cnattingius S. Perinatal outcome in SGA births defined by customised versus population based birthweight standards. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;108:830–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCowan L, Harding JE, Stewart AW. Customised birthweight centiles predict SGA pregnancies with perinatal morbidity. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;112:1026–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mongelli M, Gardosi J. Reduction of false-positive diagnosis of fetal growth restriction by application of customized fetal growth standards. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 88:844–848. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00285-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ego A, Subtil D, Grange G, et al. Customized versus population-based birth weight standards for identifying growth restricted infants: a French multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1042–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobsson B, Ahlin K, Francis A, Hagberg G, Hagberg H, Gardosi J. Cerebral palsy and restricted growth status at birth: population-based case-control study. BJOG. 2008;115:1250–1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sciscione AC, Gorman R, Callan NA. Adjustment of birth weights standards for maternal and infant characteristics improves the prediction of outcome in the small-for-gestational-age infant. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:544–7. doi: 10.1053/ob.1996.v175.a73600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]