Abstract

Memory CD8 T-cells recognizing conserved proteins from influenza A virus (IAV) such as nucleoprotein (NP), have the potential to provide protection in individuals who lack the proper neutralizing antibodies. Here we show that the most potent CD8 T-cell inducing influenza vaccine on the market (Flumist®), does not induce sufficient numbers of cross-reactive CD8 T-cells to provide substantial protection against lethal non-homologous IAV challenge. However, Flumist primed CD8 T-cells rapidly acquire memory characteristics and can respond to short interval boosting to greatly enlarge the IAV specific memory pool, sufficient to protect mice from non-homologous IAV challenge. Thus, a current vaccine strategy, Flumist, may serve as a priming platform for rapid induction of large numbers of memory CD8 T-cells with the capacity for broad protection against influenza.

Introduction

Despite the availability of a seasonal vaccine, Influenza A virus (IAV) continues to be a heavy burden on society and healthcare, infecting between 2–10% of the North American population and causing up to 500,000 annual deaths world wide (1). A major reason for the limited effectiveness of the vaccine is the high rate of mutation in the IAV hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins. This results in rapidly decreasing protection by neutralizing antibodies induced by prior seasonal vaccines (2). A vaccine that protects against a wide variety of IAV subtypes (heterosubtypic immunity, HI) would therefore be highly desirable. In contrast to the sequence variations in IAV surface proteins HA and NA, which are selected by the immunological pressure of neutralizing antibodies, internal viral components like the nucleoprotein (NP) and matrix protein (M) 1/2 are remarkably conserved over a wide range of subtype (3). Therefore in the absence of neutralizing antibodies, NP specific memory CD8 T-cells may control IAV, thereby mitigating disease symptoms and provide a first line of defense against a possible influenza pandemic. The relatively new (9 years on the market) cold adapted live attenuated nasal influenza vaccine, Flumist®, induces higher CD8 T-cell responses than the injectable IAV vaccines (4) and therefore has been speculated to provide HI (5). Whether Flumist vaccination induces sufficient cross reactive memory CD8 T-cells to provide resistance to non homologous IAV infection is unknown nor is it clear whether multiple Flumist vaccinations increase the number of these broadly protective memory CD8 T-cells. Here we address the cross protective potential of memory CD8 T-cells induced by Flumist immunization and show that specifically enhancing cross reactive CD8 T-cells through heterologous boosting of Flumist immune hosts provides a simple and potentially translational tool to broaden the protective capacity of this licensed vaccine.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Female BALB/c mice were acquired from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and housed under pathogen free conditions. After infection mice were transferred to BSL2 housing. All animal studies and procedures were approved by the University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee, under PHS assurance, Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare guidelines.

Immunization and challenges

Attenuated actA/inlB double deficient Listeria monocytogenes expressing PR8-nucleoprotein (LM-NP) was generated by Aduro BioTech, Inc. (Berkeley CA) using methodology as described (6). Vaccinia virus expressing nucleoprotein was a gift from Dr. Bennink (NIH, Bethesda MD). Recombinant NP was purchase at ImmuneTech (New York, NY). Flumist® (MedImmune, Gaithersburg MD) was purchased at the University of Iowa Hospital pharmacy. 5 μl of undiluted Flumist was introduced into each nostril while the mouse was conscious, to ensure the vaccine did not reach the lower respiratory tract (7). A/PuertoRico/8/34 (H1N1) influenza virus was grown in chicken eggs as described (8). Mice were challenged with a 10 LD50 in 50 μl PBS (2*105 TCID50), referred to as lethal dose throughout the manuscript, while lightly anesthetized with isoflurane. Body weight was monitored daily and mice were euthanized when mice had lost 30% of their starting weight in accordance with IACUC guidelines.

Viral titers

At the designated time points infected mice were euthanized, lungs were homogenized in 2 ml of DMEM and stored at −80°C until further analysis. Serial dilution of lung homogenates were co-seeded in 96 wells plates with 1*105 MDCK cells per well and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2. The next day medium was replaced with supplemented DMEM containing 0.001% Trypsin and incubated for an additional 72 hrs. To assess hemagluttination, supernatants were mixed with 0.5% v/v chicken red blood cells suspended in PBS and incubated for 60 min at 4°C.

Statistics

Unless indicated otherwise significance was calculated by one way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post test using Graphpad Prism 4 for Macintosh. P-values lower 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

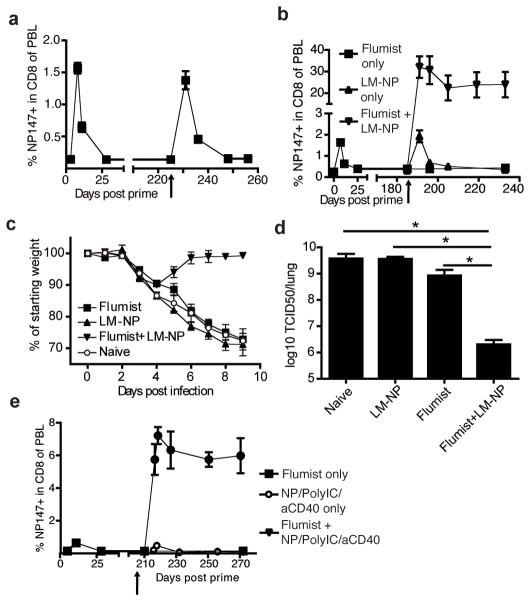

Vaccination with Flumist does not induce sufficient numbers of memory CD8 T-cells to protect mice from lethal heterosubtypic influenza challenge

The live attenuated Flumist vaccine has been reported to generate larger CD8 T-cell responses compared to injectable inactivated or subunit vaccines (4, 5) and could therefore be considered the most potent and translatable current strategy to induce IAV-specific memory CD8 T-cells. In line with this, nasal immunization of mice of BALB/c mice with Flumist induced a detectable NP147-specific CD8 T-cell response reaching 1.5% of the circulating CD8 T-cells at 8 days post immunization. However within 30 days NP147-specific CD8 T-cells in the circulation contracted to frequencies indistinguishable from naïve mice by tetramer analysis (Figure 1a). Interestingly, although the 2010/2011 Flumist contains an H1N1 (A/California/7/2009) IAV strain which has been reported to induce neutralizing antibodies against homologous challenge (9), serum from mice immunized with Flumist 40 days earlier did not contain any measurable neutralizing activity against PR8, also an H1N1 strain (Figure 1b). In contrast, serum from mice that had recovered from a sublethal PR8 challenge exhibited substantial neutralization activity against PR8 (Figure 1b, p<0.05). PR8 challenge of Flumist immunized mice is therefore similar to a scenario where individuals are infected with an IAV strain that has undergone antigenic drift and is no longer subjected to neutralization by antibodies provided by a prior infection or the seasonal IAV vaccination. To assess whether the CD8 T-cells induced by vaccination with Flumist provide protection in this scenario, mice were challenged with a lethal dose of PR8 40 days after immunization with Flumist. No decrease in peak viral titers (p=0.13 Figure 1c) and no significant increase in survival was observed (p=0.14, Figure 1d) in Flumist vaccinated mice. Some of the Flumist immune mice started to recover by day 8 post infection, whereas unimmunized mice uniformly suffered from additional weight loss until day 10 post infection (p.i.) (Figure 1d), suggesting that Flumist vaccination does provide some immunity to PR8. Recovery coincided with a substantial increase in the percentage of circulating NP147-specific CD8 T-cells at day 7 p.i., indicative of a potent secondary expansion of these cells following PR8 challenge of Flumist immune mice (Figure 1e). Moreover the limited protection Flumist provides is further reduced by depletion of CD8 T-cells prior to PR8 infection (Supplemental figure 1). Thus, immunization with Flumist results in a cross-reactive memory CD8 T-cell population, however this population seems numerically insufficient to control a non-homologous IAV infection during the first days post infection and takes at least 7 days to expand into numbers sufficient to limit disease in a fraction of immunized mice.

Figure 1.

Nasal vaccination with Flumist induces low numbers of NP147-specific memory CD8 T-cells that can greatly expand upon PR8 infection. a) BALB/c mice were intranasally immunized with Flumist and the number of circulating NP147 CD8 T-cells was determined over time. b) Neutralizing antibody activity of serum against PR8 from naïve, Flumist-immunized and PR8-immunized mice (serum from day 40 p.i.). c) Naïve and Flumist primed mice were challenged with PR8 and viral titers determined 4 days post infection and d) morbidity/mortality were assessed. Significance in survival rate was determined using Chi-square test. e) On day 7 post PR8 challenge the number of circulating NP147 CD8 T-cells in the blood was measured to evaluate the recall response. * p<0.05

Boosting can augment the Flumist-induced CD8 T-cell response to provide protection against non-homologous IAV challenge

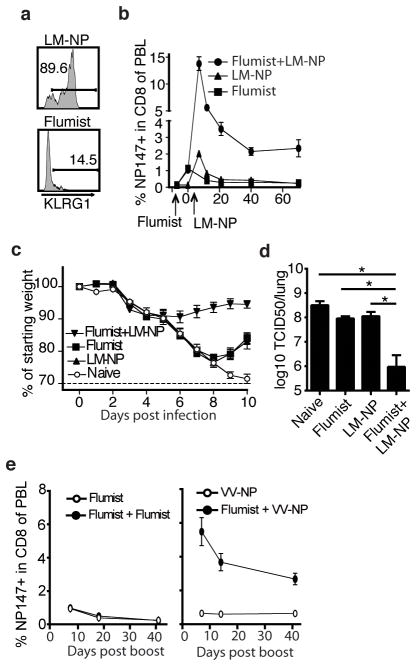

Our data suggest that the numbers of IAV-specific memory CD8 T-cells induced by Flumist vaccination are not sufficient to provide substantial protection against a non-homologous challenge. Prime boost strategies however, have been successfully applied in mice (10, 11) to induce large CD8 T-cell responses and are currently being evaluated in primates (12). As Flumist is administered annually, some individuals might have received prime-boost immunizations, but it is not known if the number of NP specific memory CD8 T-cells increases upon Flumist boosting. To address this question, mice received a second Flumist immunization 7 months after their first vaccination. Shortly after boost an increase in the frequency of circulating NP147 specific CD8 T-cell was observed (Figure 2a), suggesting that pre-existing neutralizing antibodies induced by the first immunization did not completely prevent nasal infection by Flumist. However the magnitude of the secondary response did not exceed the primary response to Flumist and no significantly increased numbers of NP147 specific memory CD8 T-cells were observed. Therefore these data suggest that annual homologous boosting with Flumist is not an effective way to increase the IAV specific memory CD8 T-cell population.

Figure 2.

Heterologous boosting of Flumist immunized mice 6–7 months after prime induces massive expansion of NP147-specific CD8 T-cells and robust protection against lethal PR8 challenge. a) BALB/c mice were primed with Flumist and were boosted after 225 days with Flumist or b) after 179 days with LM-NP (107 CFU). The NP147-specific CD8 T-cell response was tracked over time in the blood. Arrow indicates time of boost with Flumist (a) or LM-NP (b). c–d) 45 days post LM-NP boost Flumist primed mice were challenged with a lethal dose of PR8 and c) morbidity and d) lung viral titers on day 4 p.i. were determined. e) BALB/c mice were primed with Flumist and were boosted after 210 days with 50 μg recombinant NP adjuvanted with 50 μg and 10 μg anti-CD40. The NP147-specific CD8 T-cell response was tracked over time in the blood. * p<0.05

To circumvent potential neutralizing antibodies we asked whether boosting with a potent heterologous vector would effectively expand the Flumist primed NP147 specific CD8 T-cell population. actA/inlB double deficient Listeria monocytogenes (LM) are currently under clinical development (13) as a potent inducer of CD8 T-cell responses. When BALB/c mice were primed with Flumist and boosted 6 months later with actA/inlB double deficient LM expressing NP (LM-NP), a remarkable expansion of NP147-specific CD8 T-cells was observed that established a memory population exceeding 20% of all circulating CD8 T-cells (Figure 2b). Upon challenge with a lethal dose of PR8 two months post boost (Day 232), prime-boosted mice showed little weight loss (Figure 2c) and more than a 1000-fold reduction in viral titers 4 days post infection (p<0.0001, Figure 2d), compared to mice that were only primed with Flumist. Interestingly, boosting Flumist primed mice at this time point with an experimental subunit vaccine, recombinant IAV NP combined with the potent adjuvants (TLR3 agonist PolyIC and anti-CD40 (14)), also resulted in robust expansion of NP147-specific CD8 T-cells and the establishment of large memory CD8 T-cells populations (Figure 2e). Thus specifically enlarging the cross-reactive memory CD8 population by means of a live attenuated booster agent or a strongly adjuvanted subunit vaccine targeting conserved antigens appears an effective way of improving the protective potential of Flumist.

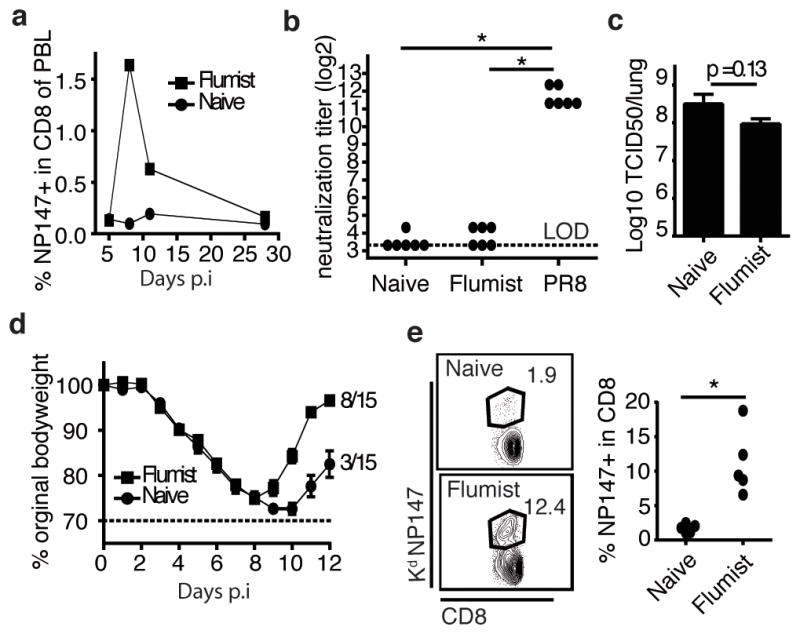

Flumist-induced CD8 T-cell response can be rapidly boosted to provide protection against non-homologous IAV challenge

LM-NP and Flumist prime a similar sized NP147 specific CD8 T-cell response in naïve animals (1.5% NP147 specific, Figure 2b). Nonetheless only LM-NP is capable of boosting NP147 specific memory CD8 T-cells in Flumist primed mice. Inducing strong inflammation is an important requisite of an effective booster agent (15), as signal 3 cytokines like type I interferon and IL-12 cause additional accumulation of effector CD8 T-cells (16). Although Flumist consists of a live replicating virus the lack of boosting by re-immunization with Flumist may suggest it does not induce strong inflammation. Consistent with, while LM-NP elicited primarily KLRG1hiNP147 specific effector CD8 T-cells, Flumist infection of naïve mice induced primarily KLRG1low NP147 specific effector CD8 T-cells (Figure 3a), which suggests the latter cells result from priming under low inflammatory conditions (17). Interestingly, a large representation of KLRG1low NP147 specific CD8 T-cells 8 days post Flumist vaccination also suggests that this population primarily consists of CD8 T-cells with early memory characteristics (18). This could mean that, CD8 T-cells induced by immunization with Flumist may be boostable shortly after priming.

Figure 3.

Flumist primed NP147-specific CD8 effector T-cells have an early memory phenotype and can be used in accelerated prime-boost generate protective immunity. a) Representative flow plot of expression of KLRG1 on KdNP147 positive CD8 T-cells from blood, 8 days post nasal immunization with LM-NP or Flumist. b) Naïve mice and mice primed with Flumist 7 days earlier were immunized with 107 CFU LM-NP (LM-NP and Flumist+LM-NP respectively) or were left unboosted (Flumist) c) On day 50 post LM-NP boost mice were challenged with a lethal dose of PR8 and morbidity and d) lung viral titers on day 4 p.i. were determined. e) Flumist primed mice were boosted 7 days later with Flumist or 5*106 PFU VV-NP. * p<0.05

Indeed, similar to boosting after 7 months, boosting Flumist primed CD8 T-cells with LM-NP 7 days post prime resulted in robust expansion of NP147 specific memory CD8 T-cells and the establishment of a large NP147 specific memory population (Figure 3b). In contrast, mice that received LM-NP without being primed with Flumist failed to establish a detectable NP147 specific memory CD8 T-cell population (Figure 3b). When challenged with a lethal dose of PR8 at a memory time point, Flumist primed – LM-NP boosted mice rapidly controlled the IAV infection, exhibiting less morbidity (Figure 3c) and significantly lower lung viral titers on day 4 post infection compared to naïve mice or mice that only received Flumist (p<0.0001 Figure 3d). Importantly, when CD8 T-cells in Flumist primed LM-NP boosted mice were depleted prior to PR8 challenge no decreased viral titers were observed (Supplemental figure 2), indicating that the protection against IAV was CD8 T-cell mediated.

Finally we assessed whether LM is the only vector capable of rapidly boosting Flumist primed CD8 T-cells. Although short interval boosting with Flumist did not enhance the numbers of NP147 specific memory CD8 T-cells (Figure 3e), boosting with vaccinia virus expressing NP (VV-NP), did result in expansion similar to LM-NP boosting. Thus Flumist primed NP specific CD8 T-cells could potentially be rapidly boosted by a relatively safe and established vaccine vector such as VV expressing NP.

Discussion

Due to constant need to reformulate seasonal vaccines and threat of pandemics the development of a universal IAV vaccine has been a major goal in the field of vaccine research. As the surface proteins HA and NA found in various subtypes are subject to rapid mutation, the conserved nature of internal viral components like NP or matrix protein has focused attention on the protective capacity of CD8 T-cells with specificity for conserved IAV proteins. Although data supports that influenza A infection elicits cross-reactive CD8 T-cells capable of eliminating infected cells after a secondary heterologous infection (19), this process does not provide life-long immunity against future influenza encounters. This conundrum has raised doubts whether CD8 T-cells can provide robust cross protection in humans (20) and clinical evidence of HI mediated by CD8 T-cells is scarce. Intranasal immunization with cold adapted attenuated IAV is currently the most efficacious licensed vaccine capable of inducing memory CD8 T-cells (21, 22). Nonetheless, in BALB/c mice, vaccination with Flumist induced too few cross-reactive memory CD8 T-cells to provide control of viral replication during the first days of non-homologous IAV infection and boosting with Flumist 7 months later did not increase the number of NP147 specific memory CD8 T-cells. Consistent with this, recent clinical studies actually suggest no increase of IAV-specific memory CD8 T-cells in children that receive the seasonal influenza vaccination annually (23) and show that repeated vaccination actually interferes with the establishment of memory CD8 T-cells after natural IAV infection due to the presence of neutralizing antibodies (24). We show that when a strong heterologous booster agent is used like LM-NP or adjuvanted NP, the numbers of cross reactive memory CD8 T-cells primed by Flumist can be dramatically increased to protect against a non-homologus IAV challenge. Importantly, we also show that Flumist induced CD8 T-cells have the unexpected property of rapid acquisition of memory characteristics and the ability to respond to short interval boosting. This is a surprising find as generally (but not exclusively (25)) immunization with live organisms are highly inflammatory and induce CD8 T-cells with a short lived effector phenotype (15, 26, 27) and delayed acquisition of memory characteristics. Therefore, it generally takes months to effectively boost CD8 T-cells primed by viral infection (11, 26) Flumist primed CD8 T-cells however, could be boosted to reach protective levels as early as 7 days post priming. This property of Flumist induced CD8 T-cells provides a potentially novel prime-boost strategy that could provide protective levels of CD8 T-cells in a matter of days. This accelerated prime-boost strategy might be very useful in the case of a sudden pandemic flu outbreak; people who were vaccinated with Flumist last season or only very recently could potentially be protected by boosting with a NP containing vector, until a traditional homologous influenza vaccine is available. Although the booster methods used in study are not approved for use in humans, both LM (13) and VV (28) based immunization have been administered safely to healthy volunteers, indicating it may be possible to develop a safe but potent CD8 T-cell inducing vaccine. As the amino acid sequence of IAV NP does not change drastically over time (3), a vector expressing NP has the potential to be mass produced and stockpiled until needed in case of a pandemic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J. Bennink (NIH) for providing VV-NP.

Support was provided by the NIH AI42767, AI085515, AI95178, AI96850, AI100527 (J.T.H.). and a Rubicon Fellowship (B.S.).

Abbreviations used in this paper

- IAV

Influenza A virus

- NP

nucleoprotein

- HA

hemagglutinin

- NA

neuraminidase

- HI

heterosubtypic immunity

- LM

Listeria monocytogenes

- VV

vaccinia virus

- TLR3

Toll like receptor 3

- IL-12

interleukin-12

- KLRG1

killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily G, member 1

Footnotes

Disclosures.

P.L. is an employee of Aduro Biotech, which holds patents related to materials used in this work.

References

- 1.Molinari NA, I, Ortega-Sanchez R, Messonnier ML, Thompson WW, Wortley PM, Weintraub E, Bridges CB. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine. 2007;25:5086–5096. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:36–44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heiny AT, Miotto O, Srinivasan KN, Khan AM, Zhang GL, Brusic V, Tan TW, August JT. Evolutionarily conserved protein sequences of influenza a viruses, avian and human, as vaccine targets. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1190. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoft DF, Babusis E, Worku S, Spencer CT, Lottenbach K, Truscott SM, Abate G, Sakala IG, Edwards KM, Creech CB, Gerber MA, Bernstein DI, Newman F, Graham I, Anderson EL, Belshe RB. Live and inactivated influenza vaccines induce similar humoral responses, but only live vaccines induce diverse T-cell responses in young children. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:845–853. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanthier PA, Huston GE, Moquin A, Eaton SM, Szaba FM, Kummer LW, Tighe MP, Kohlmeier JE, Blair PJ, Broderick M, Smiley ST, Haynes L. Live attenuated influenza vaccine(LAIV) impacts innate and adaptive immune responses. Vaccine. 2011;29:7849–7856. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.07.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinnathamby G, Lauer P, Zerfass J, Hanson B, Karabudak A, Krakover J, Secord AA, Clay TM, Morse MA, Dubensky TW, Jr, Brockstedt DG, Philip R, Giedlin M. Priming and activation of human ovarian and breast cancer-specific CD8+ T cells by polyvalent Listeria monocytogenes-based vaccines. J Immunother. 2009;32:856–869. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181b0b125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iida T, Bang FB. Infection of the upper respiratory tract of mice with influenza A virus. Am J Hyg. 1963;77:169–176. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Legge KL, Braciale TJ. Lymph node dendritic cells control CD8+ T cell responses through regulated FasL expression. Immunity. 2005;23:649–659. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang YH, Byun YH, Lee YJ, Lee YH, Lee KH, Seong BL. Cold-adapted pandemic 2009 H1N1 influenza virus live vaccine elicits cross-reactive immune responses against seasonal and H5 influenza A viruses. J Virol. 2012;86:5953–5958. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07149-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen JP, Doherty PC, Branum KC, Riberdy JM. Profound protection against respiratory challenge with a lethal H7N7 influenza A virus by increasing the magnitude of CD8(+) T-cell memory. J Virol. 2000;74:11690–11696. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11690-11696.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodland DL. Jump-starting the immune system: prime-boosting comes of age. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakhashe SK, Velu V, Sciaranghella G, Siddappa NB, Dipasquale JM, Hemashettar G, Yoon JK, Rasmussen RA, Yang F, Lee SJ, Montefiori DC, Novembre FJ, Villinger F, Amara RR, Kahn M, Hu SL, Li S, Li Z, Frankel FR, Robert-Guroff M, Johnson WE, Lieberman J, Ruprecht RM. Prime-boost vaccination with heterologous live vectors encoding SIV gag and multimeric HIV-1 gp160 protein: efficacy against repeated mucosal R5 clade C SHIV challenges. Vaccine. 2011;29:5611–5622. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le DT, Brockstedt DG, Nir-Paz R, Hampl J, Mathur S, Nemunaitis J, Sterman DH, Hassan R, Lutz E, Moyer B, Giedlin M, Louis JL, Sugar EA, Pons A, Cox AL, Levine J, Murphy AL, Illei P, Dubensky TW, Jr, Eiden JE, Jaffee EM, Laheru DA. A live-attenuated Listeria vaccine (ANZ-100) and a live-attenuated Listeria vaccine expressing mesothelin (CRS-207) for advanced cancers: phase I studies of safety and immune induction. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:858–868. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanchez PJ, McWilliams JA, Haluszczak C, Yagita H, Kedl RM. Combined TLR/CD40 stimulation mediates potent cellular immunity by regulating dendritic cell expression of CD70 in vivo. J Immunol. 2007;178:1564–1572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wirth TC, Harty JT, Badovinac VP. Modulating numbers and phenotype of CD8+ T cells in secondary immune responses. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:1916–1926. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao Z, Casey KA, Jameson SC, Curtsinger JM, Mescher MF. Programming for CD8 T cell memory development requires IL-12 or type IIFN. J Immunol. 2009;182:2786–2794. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joshi NS, Cui W, Chandele A, Lee HK, Urso DR, Hagman J, Gapin L, Kaech SM. Inflammation directs memory precursor and short-lived effector CD8(+) T cell fates via the graded expression of T-bet transcription factor. Immunity. 2007;27:281–295. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarkar S, Kalia V, Haining WN, Konieczny BT, Subramaniam S, Ahmed R. Functional and genomic profiling of effector CD8 T cell subsets with distinct memory fates. J Exp Med. 2008;205:625–640. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zweerink HJ, Courtneidge SA, Skehel JJ, Crumpton MJ, Askonas BA. Cytotoxic T cells kill influenza virus infected cells but do not distinguish between serologically distinct type A viruses. Nature. 1977;267:354–356. doi: 10.1038/267354a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dormitzer PR, Galli G, Castellino F, Golding H, Khurana S, Del Giudice G, Rappuoli R. Influenza vaccine immunology. Immunol Rev. 2011;239:167–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter NJ, Curran MP. Live attenuated influenza vaccine (FluMist(R); Fluenz): a review of its use in the prevention of seasonal influenza in children and adults. Drugs. 2011;71:1591–1622. doi: 10.2165/11206860-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forrest BD, Steele AD, Hiemstra L, Rappaport R, Ambrose CS, Gruber WC. A prospective, randomized, open-label trial comparing the safety and efficacy of trivalent live attenuated and inactivated influenza vaccines in adults 60 years of age and older. Vaccine. 2011;29:3633–3639. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bodewes R, Fraaij PL, Kreijtz JH, Geelhoed-Mieras MM, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, Rimmelzwaan GF. Annual influenza vaccination affects the development of heterosubtypic immunity. Vaccine. 2012;30:7407–7410. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bodewes R, Fraaij PL, Geelhoed-Mieras MM, van Baalen CA, Tiddens HA, van Rossum AM, van der Klis FR, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, Rimmelzwaan GF. Annual vaccination against influenza virus hampers development of virus-specific CD8 T cell immunity in children. J Virol. 2011;85:11995–12000. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05213-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bridle BW, Boudreau JE, Lichty BD, Brunelliere J, Stephenson K, Koshy S, Bramson JL, Wan Y. Vesicular stomatitis virus as a novel cancer vaccine vector to prime antitumor immunity amenable to rapid boosting with adenovirus. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1814–1821. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badovinac VP, Messingham KA, Jabbari A, Haring JS, Harty JT. Accelerated CD8+ T-cell memory and prime-boost response after dendritic-cell vaccination. Nat Med. 2005;11:748–756. doi: 10.1038/nm1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keppler SJ, Rosenits K, Koegl T, Vucikuja S, Aichele P. Signal 3 cytokines as modulators of primary immune responses during infections: the interplay of type I IFN and IL-12 in CD8 T cell responses. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berthoud TK, Hamill M, Lillie PJ, Hwenda L, Collins KA, Ewer KJ, Milicic A, Poyntz HC, Lambe T, Fletcher HA, Hill AV, Gilbert SC. Potent CD8+ T-cell immunogenicity in humans of a novel heterosubtypic influenza A vaccine, MVA-NP+M1. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1–7. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.