Abstract

Background

Weight loss is common among patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) and is mainly due to tumor and treatment related factors. The aim of the present study was to evaluate weight loss in patients with SCCHN undergoing two different radiotherapy (RT) schedules.

Material and methods

Nutritional data were analyzed from the ARTSCAN study, a controlled randomized prospective Swedish multicenter study conducted with the aim of comparing conventional fractionation (2.0 Gy per day, total 68 Gy during 7 weeks) and accelerated fractionation (1.1 + 2.0 Gy per day, total 68 Gy during 4.5 weeks). Seven hundred and fifty patients were randomized and 712 patients were followed from the start of RT in the present nutritional study.

Results

The patients had a weight loss of 11.3% (± 8.6%) during the acute phase (start of RT up to five months after the termination of RT). No difference in weight loss was seen between the two RT fractionation schedules (p = 0.839). Three factors were significantly predictive for weight loss during the acute phase, i.e. tumor site, overweight/obesity or lack of tube feeding at the start of RT. Moreover, the nadir point of weight loss occurred at five months after the termination of RT.

Conclusion

The results of the present study showed no difference in weight loss between the two RT fractionation schedules and also highlight that weight loss in SCCHN is a multifactorial problem. Moreover, the nadir of weight loss occurred at five months after the termination of treatment which calls for more intense nutritional interventions during the period after treatment.

It is well recognized that patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN) represent a group that during and after treatment suffers from nutritional impairments [1]. Though no commonly used definition of malnutrition exists internationally, the reported prevalence of malnutrition in SCCHN can vary between 20–67% [2]. Weight loss is the most important parameter used to describe nutritional status in clinical practice [2,3], particularly in combination with BMI and information about eating problems [4].

Involuntary weight loss as a result of disease is mainly due to the loss of fat free mass [5] and the weight loss seen during the treatment for SCCHN may have a number of different explanations [1,6,7]. The tumor itself may obstruct the passage of bolus thus causing swallowing problems [1,8]. Metabolic alterations can affect appetite and strength of the patient [1]. Both acute and late toxicities that arise in the treatment area due to tissue injury may have a direct impact on ability to eat [1,6]. Strategies for surveillance and treatment of nutritional impairment in patients with SCCHN are heterogeneous, and no “gold standard” is established. Knowledge of optimal nutritional strategies is incomplete and the relationship between predictive factors and weight loss is not fully known.

Radiotherapy (RT), alone or combined with surgery and/or anticancer drugs, is the mainstay for treatment of SCCHN [6,9]. Conventionally fractionated RT consists of daily absorbed doses of 1.8–2.0 Gy delivered five days a week up to a total dose of 68–70 Gy. Due to theories on rapid tumor cell proliferation, interest has been on shortening the overall treatment time, i.e. to deliver a higher absorbed dose per day (split in two fractions) resulting in a shorter overall treatment time. The ARTSCAN study, a controlled randomized Swedish multicenter study, was conducted with the aim to compare conventional fractionation (CF) versus accelerated fractionation (AF) and the effects of the treatment on outcome, overall survival and quality of life. Two-year results from the study failed to show significant differences between the two treatment schedules regarding loco-regional control, cause-specific survival and overall survival [10]. In the present study, data from the ARTSCAN study were used to investigate weight loss and related impact factors in patients undergoing CF or AF. The main objectives of the present study were to analyze weight loss over time with focus on the two RT schedules, and to explore other clinical factors for weight loss during and after RT.

Material and methods

Patients

Between November 1998 and June 2006, 750 patients with M0 SCCHN of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx or larynx (except glottic T1-2, N0) were randomized to receive either CF (2.0 Gy/day, total 68 Gy during seven weeks) or AF (1.1 Gy + 2.0 Gy/day, total 68 Gy during 4.5 weeks) as a single modality treatment or as preoperative RT. Previous malignant disease in the head and neck region, age under 18, inability to understand the information about treatment, expected non-compliance and chemotherapy closer than three months before randomization excluded patients from participating in the study. Seventeen patients were not eligible for evaluation and hence data for 733 patients were available in the ARTSCAN study. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of each participating center and written consent for participation was received from all participants. Altogether 12 treatment centers participated in the study, making it nationwide. The quality assurance program for the ARTSCAN study is described elsewhere [11]. For more information about the RT techniques and dose fractionation schedules used see Zackrisson et al. [10].

Data collection

Clinical assessments were performed every week of RT, at 4–6 weeks after the termination of RT, at five months, and thereafter every three months up to two years after the termination of RT. After that time point, patients were scheduled for follow-up every six months up to five years.

Nutritional data

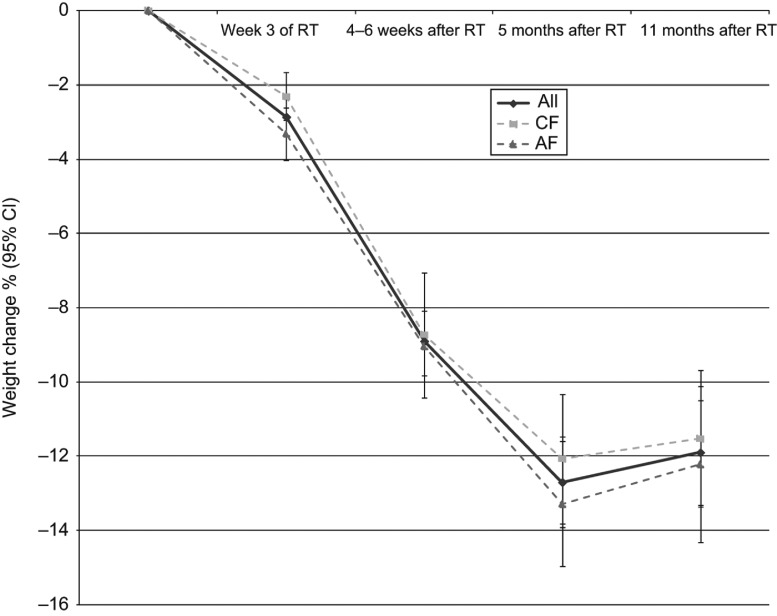

The pre-treatment weight and weight at five months after the termination of RT, here named the acute phase, were used to calculate relative percentage weight loss. Patients with weight data registrations at the start of RT, week 3 of RT, 4–6 weeks after the termination of RT and five and 11 months after the termination of RT were used to illustrate weight change over time.

Height was not recorded in the ARTSCAN database and therefore, retrospective data from the medical records were collected for 361 patients. Body mass index (BMI, weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), was calculated and the cut-off values for BMI from The European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) guidelines for nutritional screening were used in the analysis [4]. The patients were divided into three groups based on their BMI; underweight (BMI < 20), normal weight (BMI 20–25) and overweight or obese (BMI > 25). For patients over 70 years of age BMI < 22 was considered underweight and a BMI between 22 and 27 was considered normal [12].

Local guidelines for nutritional surveillance and treatment were present at the 12 participating centers. These guidelines stated that the patient should receive nutritional support when needed after the physicians’ and dieticians’ evaluation and patient approval. There were three grades of nutritional support administered during the study, i.e. oral intake (with or without dietary counseling and/or oral nutritional support), tube feeding (TF, nasogastric feeding tube or percutaneous endogastric gastrostomy) and parenteral nutrition. Only the presence of TF and parenteral nutrition were registered in the study database. The guidelines for TF use were based either on a wait-and-see procedure or prophylactic placed feeding tube, and indications for TF were not individually registered.

Clinical data

The presence of swallowing problems and use of opioid analgesics at the start and the end of RT and the presence of mucositis at the end of RT were analyzed in relation to weight loss. In the study protocol, the clinical data were scored based on the LENT-SOMA scale [13] using grades one to four, and in the analysis data were dichotomized with grades three or four defining presence of the complication. Data on performance status using the Karnofsky Performance Status Scale (KPS) [14] were also dichotomized (< 80 and ≥ 80). Patients with a KPS ≥ 80 were able to carry out normal activity and to work with no special care needed.

Statistical analyses

For the statistical analyses, the data software Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19.0 was used. The independent samples t-test and one-way between-groups ANOVA were used for continuous data and the Fisher's exact test was used as the non-parametric alternative. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to analyze variables significant in univariate analysis. Paired samples t-test and repeated measures ANOVA were used to analyze change of mean weight over time. All tests were two-sided and a p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Eligibility and patient characteristics

Weight data at the start of RT were available for 712 patients (97.1%). Of these patients, weight was available for 432 patients (60.7%) at five months after the termination of RT, while it was not available in 280 patients due to death (n = 85), residual/recurrent disease or loss of follow-up (n = 57), or missing weight data registrations (n = 138).

The majority of the patients in the studied cohort (n = 712) were men (74.4%) and the median age was 62 years (range 26–91 years). The most common tumor site was oropharyngeal cancer (48.7%) and the majority of the patients had stage III or IV disease (82.7%). Moreover, 261 of 712 patients (36.7 %) were treated with surgery (resection of primary tumor, neck dissection or both) after RT as part of their tumor treatment. The patients were evenly distributed to receive either AF (49.9%) or CF (50.1%).

Development of acute treatment toxicities

The development of treatment toxicities at the start and the end of RT were analyzed according to the two fractionation schedules (n = 712). No significant difference was seen between the two fractionation schedules for the characteristics (swallowing problems and opioid analgesics) studied at the start of RT. However, significantly more patients treated with AF were reported to have swallowing problems (AF 56.9%, CF 43.1%, missing n = 38), mucositis (AF 54.2%, CF 45.8%, missing n = 51) and used opioid analgesics (AF 58.6%, CF 41.4%, missing n = 39) more frequently at the end of RT (p < 0.001, 0.001 and 0.001, respectively).

Characteristics for tube feeding administration during RT

Administration of TF at the start and end of RT was analyzed together with patient-, tumor- and treatment data (n = 712) (Table I). At the start of RT, 76 (10.7%) patients (missing n = 5) received TF and the corresponding number at the end of RT was 335 patients (47.1%) (missing n = 43). At the start of RT older patients (≥ 65 years), patients with tumor of the hypopharynx or oral cavity, patients with stage IV disease, patients with a low BMI or KPS (< 80), patients with swallowing problems or patients treated with opioid analgesics received TF more frequently. At the end of RT patients treated with AF received TF more frequently than patients treated with CF (p < 0.001). Other characteristics for receiving TF at the end of RT were: tumor of the hypopharynx or oral cavity, a low BMI at the start of RT or swallowing problems, mucositis or treatment with opioid analgesics at the end of RT.

Table I.

Characteristics for use of tube feeding (TF) at the start and the end of radiotherapy (RT) (n = 712).

| Start RT, n (%) |

End RT, n (%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Use of TF | No TF | P* | Missing | Use of TF | No TF | P* | Missing |

| Age | ||||||||

| < 65 years ≥ 65 years |

36 (8.2) 40 (14.9) |

403 (91.8) 228 (85.1) |

0.006

|

5 |

200 (48.0) 135 (53.6) |

217 (52.0) 117 (46.4) |

0.175 |

43 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male Female |

60 (11.4) 16 (8.8) |

465 (88.6) 166 (91.2) |

0.405 |

5 |

249 (50.3) 86 (49.4) |

246 (49.7) 88 (50.6) |

0.860 |

43 |

| Site | ||||||||

| Oropharynx Larynx Hypopharynx Oral cavity |

23 (6.7) 11 (7.4) 30 (25.4) 12 (12.6) |

322 (93.3) 138 (92.6) 88 (74.6) 83 (87.4) |

< 0.001

|

5 |

161 (48.8) 53 (38.4) 75 (66.4) 46 (52.3) |

169 (51.2) 85 (61.6) 38 (33.6) 42 (47.7) |

< 0.001

|

43 |

| Clinical stage | ||||||||

| I II III IV |

1 (3.3) 5 (5.4) 17 (8.7) 53 (13.6) |

29 (96.7) 87 (94.6) 178 (91.3) 337 (86.4) |

0.041

|

5 |

13 (43.3) 37 (41.1) 89 (48.4) 196 (53.7) |

17 (56.7) 53 (58.9) 95 (51.6) 169 (46.3) |

0.134 |

43 |

| Treatment modality | ||||||||

| CF AF |

35 (9.8) 41 (11.7) |

322 (90.2) 309 (88.3) |

0.467 |

5 |

126 (38.3) 209 (61.5) |

203 (61.7) 131 (38.5) |

< 0.001

|

43 |

| BMI‡ | ||||||||

| Underweight Normal weight Overweight/obese |

8 (18.2) 13 (9.3) 5 (2.9) |

36 (81.8) 127 (90.7) 170 (97.1) |

0.001

|

353 |

25 (62.5) 60 (45.1) 67 (40.1) |

15 (37.5) 73 (54.9) 100 (59.9) |

0.041

|

372 |

| Karnofsky | ||||||||

| < 80 ≥ 80 |

19 (33.3) 50 (8.1) |

38 (66.7) 565 (91.9) |

< 0.001

|

40 |

–†

|

–†

|

–†

|

–†

|

| Swallowing problem | ||||||||

| Yes No |

52 (53.1) 24 (3.9) |

46 (46.9) 585 (96.1) |

< 0.001

|

5 |

322 (62.8) 11 (7.1) |

191 (37.2) 143 (92.9) |

< 0.001

|

45 |

| Mucositis | ||||||||

| Yes No |

–†

|

–†

|

–†

|

–†

|

295 (51.7) 30 (35.7) |

276 (48.3) 54 (64.3) |

0.007

|

57 |

| Use of opioid analgesics | ||||||||

| Yes No |

29 (39.2) 47 (7.4) |

45 (60.8) 584 (92.6) |

< 0.001 | 7 | 217 (66.8) 116 (34.0) |

108 (33.2) 225 (66.0) |

< 0.001 | 46 |

| Number of patients, n (%) | 76 (10.7) | 631 (88.6) | 5 (0.7%) | 335 (47.1) | 334 (46.9) | 43 (6.0) | ||

*p-value controlled by Fisher's Exact Test; †Data not recorded at that time point; ‡ Underweight: BMI < 20 (BMI < 22 if ≥ 70 years); normal weight: BMI 20–25 (BMI 22–27 if ≥ 70years); overweight/obese: BMI > 25 (BMI > 27 if ≥ 70 years).

Characteristics for weight loss during the acute phase

Weight loss during the acute phase was analyzed in relation to patient-, tumor-, treatment and nutritional treatment characteristics (n = 432) (Table II). There was a significant decrease in mean weight with 9.4 kg (± 7.9) during the acute phase (p < 0.001) which corresponded to a weight loss of 11.3% (± 8.6%). No difference in weight change was seen in patients treated with AF and CF (p = 0.839). Weight loss during the acute phase could significantly be explained by the following characteristics: age < 65 years, oropharyngeal tumor, a high BMI at the start of RT, a high KPS (≥ 80) at the start of RT, absence of swallowing problems at the start of RT, lack of TF at the start of RT and presence of mucositis at the end of RT.

Table II.

Characteristics for weight loss during the acute phase (n = 432). Weight change percent at five months after the end of radiotherapy (RT) is shown in relation to initial weight taken at the start of RT (mean [SD]).

| Acute phase Weight change (%), mean [SD] |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | All | P* | Missing | |||||

| Weight change total | −11.3 [8.6] | |||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| < 65 years ≥ 65 years |

−12.0 [8.1] −10.1 [9.3] |

0.032

|

− |

|||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male Female |

−11.6 [8.5] −10.7 [8.9] |

0.371 |

− |

|||||

| Site | ||||||||

| Oropharynx Larynx Hypopharynx Oral cavity |

−13.7 [7.9] −8.6 [7.7] −8.4 [9.8] −9.0 [8.9] |

< 0.001

‡

0.002 § |

− |

|||||

| Clinical stage | ||||||||

| I II III IV |

−11.8 [6.5] −10.0 [8.2] −10.2 [8.0] −12.4 [8.6] |

0.088 – 0.999‖

|

− | |||||

| BMI† | ||||||||

| Underweight Normal weight Overweight/obese |

−3.5 [9.1] −9.3 [7.5] −14.5 [7.3] |

< 0.001

¶

0.003** |

178 |

|||||

| Treatment modality | ||||||||

| CF AF |

−11.3 [8.1] −11.4 [9.0] |

0.839 |

− |

|||||

| Surgery | ||||||||

| Yes No |

−12.1 [8.0] −10.9 [9.0] |

0.150 |

− |

|||||

| Karnofsky start | ||||||||

| < 80 ≥ 80 |

−5.9 [10.3] −11.6 [8.4] |

0.002

|

21 |

|||||

| Swallowing problems start RT | ||||||||

| Yes No |

−7.1 [10.4] −11.7 [8.3] |

0.003

|

1 |

|||||

| Swallowing problems end RT | ||||||||

| Yes No |

−11.9 [8.8] −10.1 [7.9] |

0.076 |

14 |

|||||

| Mucositis end RT | ||||||||

| Yes No |

−12.0 [8.3] −6.6 [9.3] |

< 0.001

|

21 |

|||||

| Use of opioid analgesics start RT | ||||||||

| Yes No |

−10.4 [10.7] −11.4 [8.4] |

0.547 |

3 |

|||||

| Use of opioid analgesics end RT | ||||||||

| Yes No |

−12.1 [8.6] −10.8 [8.6] |

0.118 |

15 |

|||||

| Tube feeding start RT | ||||||||

| Yes No |

−5.7 [11.0] −11.8 [8.3] |

< 0.001

|

4 |

|||||

| Tube feeding end RT | ||||||||

| Yes No |

−10.8 [9.2] −11.9 [8.1] |

0.212 | 17 | |||||

*p-value controlled by Independent samples T-test or One way ANOVA; † Underweight: BMI < 20 (BMI < 22 if ≥ 70 years); normal weight: BMI 20–25 (BMI 22–27 if ≥ 70years); overweight/obese: BMI > 25 (BMI > 27 if ≥ 70 years); ‡ p-value when comparing tumor of the oropharynx against tumors of the larynx and hypopharynx; § p-value when comparing tumor of the oropharynx against tumor of the oral cavity; ‖ no significant values for weight change, range p-values (min, max); ¶ p-value when comparing BMI overweight/obese with BMI underweight and BMI normal weight; **p-value when comparing BMI underweight with BMI normal weight.

A multiple linear regression analysis was used to make a model of the significant variables from the univariate analysis to predict weight loss during the acute phase (n = 230). Weight loss during the acute phase was used as the dependent variable (numerical). Seven independent variables were used in the model: age grouped as < 65 and ≥ 65 years, tumor site (oropharynx, oral cavity, larynx or hypopharynx), BMI at the start of RT grouped as underweight, normal weight or overweight/obese, Karnofsky at the start of RT grouped as < 80 or ≥ 80, presence of TF at the start of RT (yes/no), swallowing problems at the start of RT (yes/no) and mucositis at the end of RT (yes/no). The coefficient of correlation R2 for the model including all seven independent variables was 27.8% (p < 0.001). Three variables were significantly predictive for weight loss during the acute phase: tumor site, BMI and TF. Patients with tumor of the oropharynx had a significantly larger weight loss during the acute phase compared with patients having tumors of the larynx (B = 3.626, p = 0.008) or oral cavity (B = 3.787, p = 0.018). No significant difference was seen between patients with tumors of the oropharynx or hypopharynx (B = 1.658, p = 0.316). Furthermore, patients with overweight or obesity according to the BMI classification demonstrated significantly greater weight loss than patients with normal weight (B = 4.220, p < 0.001) or underweight (B = 10.058, p < 0.001). Moreover, patients without TF at the start of RT had a significantly greater weight lost compared with patients receiving TF (B = 6.427, p = 0.006).

Weight change over time

A total of 175 patients had weight data registrations at five time points from the start of RT up to 11 months after the termination of RT. An analysis of weight change over time was performed for these patients (Figure I). The figure shows a rapid weight loss during RT, which continues after RT with a nadir of weight loss at five months after the termination of RT. When analyzing the same subgroup of patients, mean weight (kg) changed significantly over time (p < 0.001). There was a significant decrease in mean weight (kg) between each of the different time points, except for mean weight change between five and 11 months after the termination of RT (p = 0.415).

Figure 1.

Weight change in % (mean ± 95% CI) from the start of RT up to different time points during and after the termination of RT (n = 175). The data are presented in total and divided by patients receiving conventional fractionation (CF, n = 79) and accelerated fractionation (AF, n = 96).

Discussion

This study comprises a secondary study based on nutritional data with 712 patients with head and neck cancer. The main result of the present study was that no significant difference in weight loss during the acute phase could be observed between the two RT fractionation schedules. Explanatory factors for the weight loss seen during that time period were tumor location, BMI and TF. A rapid weight loss over time was seen during and after treatment, with a nadir at five months after the termination of RT.

The result from the present study showed that tumor of the oropharynx was a strong predictive factor for weight loss during the acute phase which also has been described in earlier studies [8,15]. Patients with tumors of the oral cavity and oropharynx have in general impaired swallowing function prior to treatment [8]. A high BMI at the start of RT was another characteristic important for weight loss during the acute phase. Previous studies show conflicting results when considering pretreatment BMI as a predictor for weight loss and use of nutritional support during RT [16,17]. The reason why patients with a low BMI in the present study experienced less weight loss can be due to that these patients received TF more frequently. This could have been the result of an attitude, both by the health care professionals and the patients that patients with a higher BMI might be in a better nutritional balance than patients with a lower BMI. As evident, weight loss in SCCHN is a multifactorial problem and therefore, more studies are warranted to further identify characteristics for weight loss in SCCHN in a longer perspective after the termination of RT.

No attempt was made in the ARTSCAN trial to use the same guidelines for TF at every participating center. Instead a wait-and-see attitude for TF was evident, as only 10.7% of the patients received TF at the start of RT. The prevalence of tube feeding (TF) use in SCCHN shows a wide range (4–60%) depending on at which time point the patient receives the nutritional support as the routines for placement of feeding tube varies between different treatment centers internationally [18]. The present study showed that patients with TF placed at the start of RT showed less weight loss during the acute phase, and due to the wait-and-see attitude patients with poor general condition got TF more frequently. Additionally, patients treated with AF received TF more frequently at the end of RT compared with patients treated with CF. The pattern of use of TF may therefore offer an explanation as to why a difference in weight loss between the two treatment schedules could not be demonstrated, although patients treated with AF experienced more acute treatment toxicity at the end of RT compared to patients treated with CF.

Use of TF at the start of RT in the present study was dependent on factors such as age, tumor site and clinical stage, BMI, KPS, swallowing problems and use of opioid analgesics. At the end of RT, tumor location was still a characteristic for use of TF along with fractionation type, BMI, swallowing problems, mucositis and use of opioid analgesics. Weight loss prior to treatment, tumor site and stage, RT dose, a combinational treatment approach, amongst others, have earlier been stated in the literature as factors that increase the use of TF [7,16,18]. Furthermore, it is important to consider complications related to percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy insertion with the most common severe complication being wound infection [19]. Recent awareness has also arisen about whether the presence of a feeding tube makes the patient less willing to eat leading to swallowing muscle atrophy [20]. Still, many authors have highlighted the benefits of TF use in SCCHN [21,22] as well as the benefits with prophylactic placed feeding tubes [7,23,24]. A comprehensive review from 2011 discusses the issue more indepth and concludes that it seems to be both advantages and disadvantages regarding prophylactic placed feeding tubes in SCCHN and that the overall picture is not fully known [18]. Due to the lack of conclusive answers, The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition states in their cancer guidelines that “nutrition support therapy should not be used routinely in patients undergoing head and neck irradiation,” and that nutritional support “is appropriate in patients who are already malnourished and who are anticipated to be unable to ingest and/or absorb adequate nutrition for a prolonged period of time” [25]. In other words, without clear evidence an individual evaluation of the need of nutritional support must be present, and more studies are needed to understand when and to whom TF should best be administered and the longitudinal benefits with TF.

The longitudinal pattern of weight loss found in this study confirms earlier findings within this area [17]. The patients in the present study had a rapid decrease in weight during the acute phase with a percentage weight loss of 11.3%. When illustrating weight change over time, the nadir of weight loss occurred at the five month follow-up after the termination of RT. More time points than presented in the current study are needed to examine the true value of the nadir of weight loss in SCCHN. Nonetheless, the result of the present study underline the fact that these patients continue to lose weight after the termination of RT which calls for the importance of a prolonged follow-up in this patient group with focus on eating difficulties.

The ARTSCAN study was primarily not designed with the focus on investigating nutritional data, which is important to consider when interpreting the results. The results of our study present a risk of being biased due to missing weight registrations at follow-up, probably due to inadequate routines in clinical practice. Moreover, as no “gold standard” for nutritional support in this patient group is established, it was left to each participating center to give nutritional support following local guidelines, i.e. no standardized nutritional treatment was given. This limitation of the present study makes it difficult to give clear answers to how the use of nutritional support might have affected weight loss and different impact factors for weight loss. Since few patients received TF at the start of RT, it was not possible to include significant interaction effects between TF and the other variables in the multivariate model. Moreover, due to death, residual/recurrent disease, loss of follow-up or missing weight data registrations, the number of patients was reduced at follow-up which limited the amount of data available for the multivariate analysis. The low explanation rate by the multiple linear regression analysis leaves a number of questions unanswered regarding predictive factors for weight loss in SCCHN.

In summary, weight loss in patients with SCCHN during the acute phase could be explained, in part, by tumor location, BMI and TF which underlines that there are still questions left to answer in this multifactorial problem. No significant difference in weight loss during the acute phase was seen between the two fractionation schedules despite that treatment toxicities were more prevalent in patients receiving AF. The patients in the present study lost 11.3% during the acute phase, with a nadir at the assessment five months after the termination of RT. This calls for a frequent and prolonged follow-up for patients with SCCHN with focus on remaining treatment toxicities and nutritional impairments after the termination of RT.

Acknowledgements

The study was made possible by the commitment from the staff at the participating centers in the ARTSCAN study – Umeå University Hospital, Lund University Hospital, Karolinska University Hospital at Solna and at Huddinge, Stockholm, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Göteborg, Örebro University Hospital, Malmö University Hospital, Karlstad Central Hospital, Linköping University Hospital, Gävle Hospital, Ryhov County Hospital, Jönköping, and Uppsala University Hospital. The authors acknowledge Ove Björ for statistical advice.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Cancer Society, Laryngfonden (Sweden), Lions Cancer Research Foundation at Umeå University and the Cancer Research Foundation of Northern Sweden. The study sponsors had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis and writing or in the decision to submit the manuscript.

References

- 1.Chasen MR, Bhargava R. A descriptive review of the factors contributing to nutritional compromise in patients with head and neck cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1345–51. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0684-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, van Leeuwen PA, Sauerwein HP, Kuik DJ, Snow GB, Quak JJ. Assessment of malnutrition parameters in head and neck cancer and their relation to postoperative complications. Head Neck. 1997;19:419–25. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199708)19:5<419::aid-hed9>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ravasco P, Monteiro-Grillo I, Vidal PM, Camilo ME. Nutritional deterioration in cancer: The role of disease and diet. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2003;15:443–50. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(03)00155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kondrup J, Allison SP, Elia M, Vellas B, Plauth M. ESPEN guidelines for nutrition screening 2002. Clin Nutr. 2003;22:415–21. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(03)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silver HJ, Dietrich MS, Murphy BA. Changes in body mass, energy balance, physical function, and inflammatory state in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer treated with concurrent chemoradiation after low-dose induction chemotherapy. Head Neck. 2007;29:893–900. doi: 10.1002/hed.20607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vissink A, Jansma J, Spijkervet FKL, Burlage FR, Coppes RP. Oral sequelae of head and neck radiotherapy. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:199–212. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaver ME, Matheny KE, Roberts DB, Myers JN. Predictors of weight loss during radiation therapy. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:645–8. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.120428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pauloski BR, Rademaker AW, Logemann JA, Stein D, Beery Q, Nweman L, et al. Pretreatment swallowing function in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 2000;22:474–82. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200008)22:5<474::aid-hed6>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehanna H, West CML, Nutting C, Paleri V. Head and neck cancer – Part 2: Treatment and prognostic factors. BMJ Open. 2010;341:721–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zackrisson B, Nilsson P, Kjellén E, Johansson K-A, Modig H, Brun E, et al. Two-year results from a Swedish study on conventional versus accelerated radiotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma – The ARTSCAN study. Radiother Oncol. 2011;100:41–8. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johansson K-A, Nilsson P, Zackrisson B, Ohlson B, Kjellén E, Mercke C, et al. The quality assurance process for the ARTSCAN head and neck study – a practical interactive approach for QA in 3DCRT and IMRT. Radiother Oncol. 2008;87:290–9. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vallén C, Hagell P, Westergren A. Validity and user- friendliness of the minimal eating observation and nutrition form – version II (MEONF-II) for undernutrition risk screening. Food Nutr Res. 2011;55 doi: 10.3402/fnr.v55i0.5801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.EORTC Late Effects Working Group. LENT SOMA tables. Radiother Oncol. 1995;35:17–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mor V, Laliberte L, Morris JN, Wiemann M. The Karnofsky Performance Status Scale: An examination of its reliability and validity in a research setting. Cancer. 1984;53:2002–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840501)53:9<2002::aid-cncr2820530933>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jager-Wittenaar H, Dijkstra PU, Vissink A, van der Laan BF, van Oort RP, Roodenburg JL. Critical weight loss in head and neck cancer – prevalence and risk factors at diagnosis: An explorative study. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:1045–50. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangar S, Slevin N, Mais K, Sykes A. Evaluating predictive factors for determining enteral nutrition in patients receiving radical radiotherapy for head and neck cancer: A retrospective review. Radiother Oncol. 2006;78:152–8. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ehrsson YT, Langius-Eklöf A, Laurell G. Nutritional surveillance and weight loss in head and neck cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:757–65. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1146-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Locher JL, Bonner JA, Carroll WR, Caudell JJ, Keith JN, Kilgore ML, et al. Prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement in treatment of head and neck cancer. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:365–74. doi: 10.1177/0148607110377097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ehrsson YT, Langius-Eklöf A, Bark T, Laurell G. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) – a long-term follow-up study in head and neck cancer patients. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004;29:740–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langmore S, Krisciunas GP, Miloro KV, Evans SR, Cheng DM. Does PEG use cause dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients? Dysphagia. 2012;27:251–9. doi: 10.1007/s00455-011-9360-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zogbaum AT, Fitz P, Duffy V. Tube feeding may improve adherence to radiation treatment schedule in head and neck cancer: An outcomes study. Top Clin Nutr. 2004;19:95–106. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senft M, Fietkau R, Iro H, Sailer D, Sauer R. The influence of supportive nutritional therapy via percutaneous endoscopically guided gastrostomy on the quality of life of cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 1993;1:272–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00366049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silander E, Nyman J, Bove M, Johansson L, Larsson S, Hammerlid E. Impact of prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy on malnutrition and quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer – a randomized study. Head Neck. 2012;34:1–9. doi: 10.1002/hed.21700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Assenat E, Thezenas S, Flori N, Pere-Charlier N, Garrel R, Serre A, et al. Prophylactic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in patients with advanced head and neck tumors treated by combined chemoradiotherapy. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42:548–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.August DA, Huhmann MB. ASPEN clinical guidelines: Nutrition support therapy during adult anticancer treatment and in hematopoietic cell transplantation. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009;33:472–500. doi: 10.1177/0148607109341804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]