Abstract

Aging leads to reduced cellular immunity with consequent increased rates of infectious disease, cancer and autoimmunity in the elderly. The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) modulates innate and adaptive immunity via innervation of lymphoid organs. In aged Fischer 344 (F344) rats, noradrenergic (NA) nerve density in secondary lymphoid organs declines, which may contribute to immunosenescence with aging. These studies suggest there is SNS involvement in age-induced immune dysregulation.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to longitudinally characterize age-related change in sympathetic innervation of the spleen and sympathetic activity/tone in male Brown Norway (BN) rats, which live longer and have a strikingly different immune profile than the F344 rat, the traditional animal model for aging research.

Methods

Splenic sympathetic neurotransmission was evaluated between 8 and 32 months of age by (1) NA nerve fiber density; (2) splenic norepinephrine (NE) concentration; and (3) circulating catecholamines levels after decapitation.

Results

We report a decline in noradrenergic nerve density in splenic white pulp (45%) at 18 months of age compared with 8 month-old (M) rats, which is followed by a much slower rate of decline between 18 and 32 months. Lower splenic NE concentrations were consistent with morphometric findings. Circulating catecholamines levels generally dropped with increasing age.

Conclusion

These findings suggest there is a sympathetic-to-immune system dysregulation beginning at middle age. Given the unique T-helper-2 bias in Brown Norway rats, altered sympathetic-immune communication may be important for understanding the age-related rise in asthma and autoimmunity.

Keywords: noradrenergic nerves, secondary lymphoid organ, stress-induced plasma catecholamines, fluorescence histochemistry, cardiovascular measures, aged

1. INTRODUCTION

The central nervous system (CNS) regulates immune function, at least in part, via noradrenergic (NA) sympathetic nerves that innervate primary and secondary immune organs (reviewed in Bellinger et al., 2008b). Norepinephrine (NE) released by sympathetic nerves interacts with adrenergic receptors (AR) expressed on the surface of cells of the immune system (reviewed in Kin and Sanders, 2006; Bellinger et al., 2008b). The sympathetic nervous system (SNS) modulates many aspects of immune function. Based on in vitro and in vivo studies in young adult rodents, the roles ascribed to the SNS include: (1) limiting the magnitude of both acute and chronic inflammatory responses by shifting the cytokine balance from a pro-inflammatory towards an anti-inflammatory cytokine profile (Vizi and Elenkov, 2002); (2) promoting T-helper-2 (Th2)-driven antibody responses via β2-AR signaling of B cells by up-regulating B cell accessory molecule expression and increasing B cell responsiveness to interleukin (IL)-4 (reviewed in Kin and Sanders, 2006); (3) enhancing cell-mediated responses, such as a delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) reaction to a contact sensitizing agent through direct interaction with both T cells and antigen-presenting cells (Madden et al., 1989; Li et al., 2004); and (4) influencing Th1-driven antibody responses through β2-AR stimulation of Th1 cells (Madden et al., 1995; Kruszewska et al., 1995; reviewed in Kin and Sanders, 2006; Bellinger et al., 2005). In general, agents that activate the SNS tend to reduce T cell responses (Madden et al., 1989; Sanders et al., 1997; reviewed in Kin and Sanders, 2006), anti-viral immune reactivity (Dobbs et al., 1993), and natural killer (NK) cell activity (Irwin et al., 1988). Collectively, studies performed in young adult rodents demonstrate that genetic background, gender, site of immunization, type of immune cells involved in the immune response, and timing of exposure to catecholamines during the immune response all contribute to the complexity of SNS interactions with the immune system and affect the outcome of SNS modulation of the immune response (Madden et al., 1995; Kin and Sanders, 2006; Bellinger et al., 2008b). Furthermore, these complexities likely reflect an important role of the SNS in fine-tuning an immune response with the goal of effectively eliminating the threat to the host and restoring immune system homeostasis.

NA innervation of, and NE content in, secondary lymphoid organs, such as the spleen, can be affected by physiological changes (i.e., immune challenge or immunosuppression) (Yang et al., 1998; Lorton et al., 2008), immunodeficiency virus infection (Kelley et al., 2003; Sloan et al., 2008), psychosocial stress (Sloan et al., 2007), hypertension (Purcell and Gattone, 1992), pregnancy and parturition (Bellinger et al., 2001) and with advancing age (Bellinger et al., 1987, 2001, 2002). Age-related changes in sympathetic innervation of the spleen are species- and/or strain-specific. For example, sympathetic NA innervation of spleens from aged C57Bl/6J and BALB/cJ mice is preserved (Madden et al., 1997; Bellinger et al., 2001), but declines with advancing age in male C3H, MRL-lpr/lpr (Breneman et al., 1993) and New Zealand mice (NZB, NZW, and NZBW) (Bellinger et al., 1989). In murine strains that develop autoimmune diseases (MRL lpr/lpr, NZB and NZBW) the onset of sympathetic nerve loss in the spleen occurs with, or slightly precedes the onset of the autoimmune disease (Breneman et al., 1993; Bellinger et al., 1989).

In a previous study from our laboratory (Bellinger et al., 2002) we compared sympathetic innervation of the spleen in four strains of young (3-month-old (M)) and old (21M) rats. These strains of rats were chosen for study because they are commonly used as models for human aging and/or used to study neural-immune interactions. We reported that NA innervation of spleens from male Fischer 344 (F344) and Lewis rats decline in normal aging, whereas NA innervation was preserved in age-matched Brown Norway (BN) and BN X F344 (F1; BNF1) rats. The reason for this strain difference is unclear, but maybe a result of the BN and BNF1 rats having a longer life span (median age 32M) than F344 and Lewis rats (median age 24M) (Nadon, 2004). Unlike F344 rats, the most commonly used rat model for aging, in BN rats there is low morbidity from pituitary adenomas or glomerulonephrosis with increasing age (Lipman et al., 1996, 1999; Nadon, 2004). BN and F344 rats also differ in their behavior (Rex et al., 1996; Ramos et al., 1997), learning and memory (van der Staay et al., 1996), immune function (Sado et al., 1986; Koch 1976; Stankus and Leslie 1976; Festing, 1998; Lipman, 1996, 1999), and stress responses (Segar et al., 2008; Duclos et al., 2005; Sarrieau et al., 1998; Gómez et al., 1998), which may affect NA nerve integrity in the spleen with advancing age.

The purpose of the present study was to longitudinally examine the effect of age on sympathetic NA innervation of spleens from BN rats. Since age-related changes in SNS and sympatho-adrenal medullary system (SAM) reactivity may contribute to age-induced changes in NA nerve integrity and splenic NE content via increased local catecholamine concentrations influencing uptake into the nerve terminals from the circulation, local sympathetic nerve activity, and/or affecting leukocyte migration (Bellinger et al., 2008b; Elenkov et al,. 2000; Madden et al., 1995), SNS and SAM reactivity to decapitation stress was also assessed by measuring circulating catecholamine levels (NE and epinephrine (EPI), respectively). We report here an age-related decline in NA nerve density in the splenic white pulp, evident by morphometric analysis at 18 months of age, and reduced splenic NE concentration between 18 and 32 months of age. Decapitation stress-induced plasma catecholamine levels were diminished in middle aged and aged rats. Given the well documented role of the SNS in immune modulation, altered sympathetic innervation likely affects immune competence in aging BN rats.

RESULTS

3.1. Fluorescence Histochemistry for Catecholamines in the Spleen

In young adult rats (8M), dense plexuses of NA fibers entered the spleen with the splenic artery and its branches. The greatest density of NA nerves was found in the white pulp associated with the central arteriole and its branches (Fig. 1A). Fluorescent NA nerve fibers extend from these vascular plexuses into the periarteriolar lymphatic sheath (PALS) among lymphocytes and macrophages, as either linear or punctate profiles. NA nerve fibers also course as less dense plexuses along the venous sinuses and trabeculae in the red pulp, but are rarely found in splenic follicles, where B cells predominantly reside.

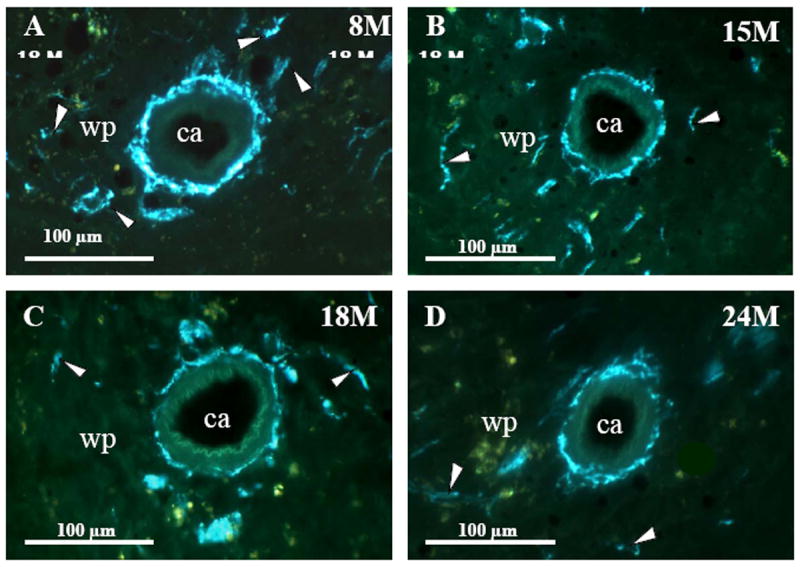

Fig. 1. NA Nerves in the Splenic White Pulp across Age.

Fluorescence histochemistry for localizing catecholamines revealed a dense plexus of bluish-green fluorescent noradrenergic (NA) nerves surrounding the central arteriole (ca) and in the adjacent white pulp (wp; indicated by arrowheads) of spleens from 8M (A). In 15M (B) rats, NA innervation was diminished compared with 8M rats, a change that persisted through 32 months of age (C-F). These photographs are representative of NA innervation of spleens from all animals in each treatment group. 18M (C), 24M (D), 27M (E), and 32M (F) BN rats. Calibration bar = 100 μm.

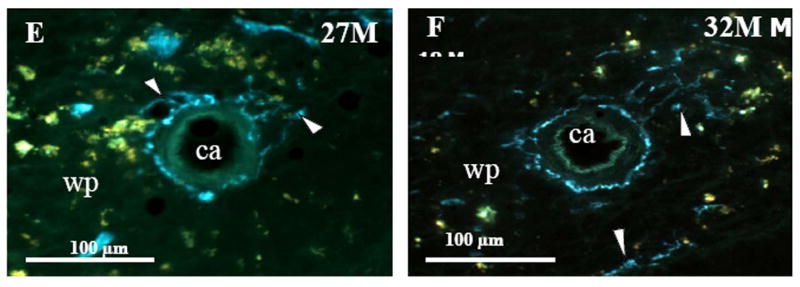

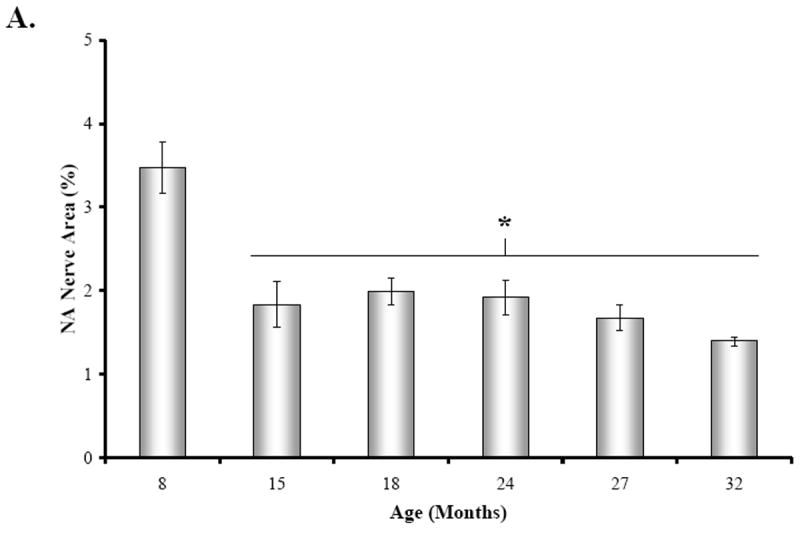

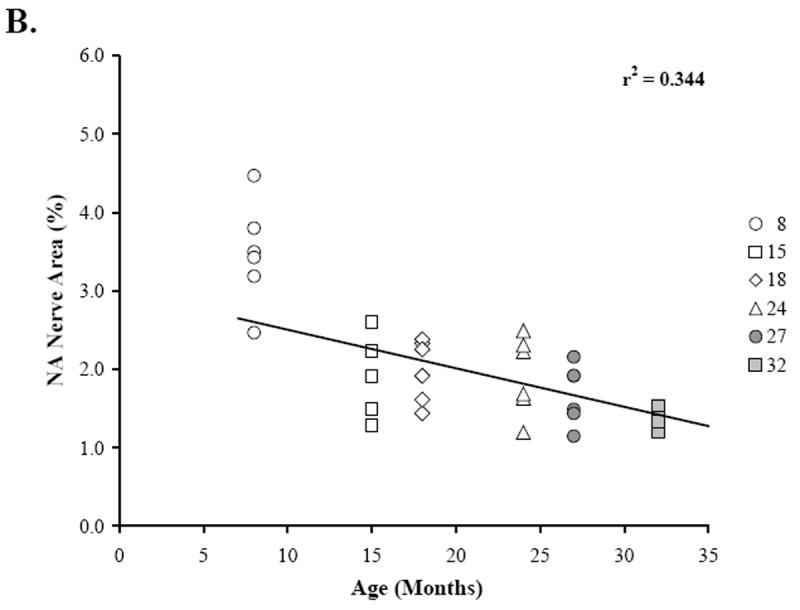

At 15 months of age, a decline in NA nerve density was observed in all compartments of the spleen, but most strikingly in the white pulp along the central arteriole (Fig. 1B). Between 18 and 32 months of age, the density of NA plexuses in the splenic white pulp, along the central arteriole (Fig. 1C-1F) and other regions of the spleen appeared comparable to that seen at 15 months of age. Morphometric analysis of fluorescent nerve profiles in the splenic white pulp across age (Fig. 2A) confirmed our qualitative assessment of sympathetic innervation (F(5,30) = 15.14, p < 0.0001). There was a significant reduction in the mean percentage of NA nerve area in spleens from 15M to 32M rats compared with 8M rats (p < 0.001). A scatter plot showing the percent area of NA nerve fibers in splenic white pulps across age is shown in Fig. 2B. Linear regression analysis revealed a significant negative correlation (p < 0.0001) between sympathetic nerve area and increasing age.

Fig. 2. Effect of Age on Mean Percentage of NA Nerve Area in the Splenic White Pulp.

A. The mean percent area of noradrenergic (NA) nerves in splenic white pulps was significantly reduced (*, p < 0.0001) between 15 and 32 months of age. Four white pulp regions from 6 rats per age group were used to quantify nerve area and data are expressed as mean of mean ± SEM. B. A scatter plot demonstrates the distribution of splenic NA nerve expressed as a percentage of sample area in the white pulp across age expressed in months. The line of best fit shows that NA nerve area is negatively associated (r2 = 0.344; p < 0.0001) with age.

3.2. NE Concentration in the Spleen

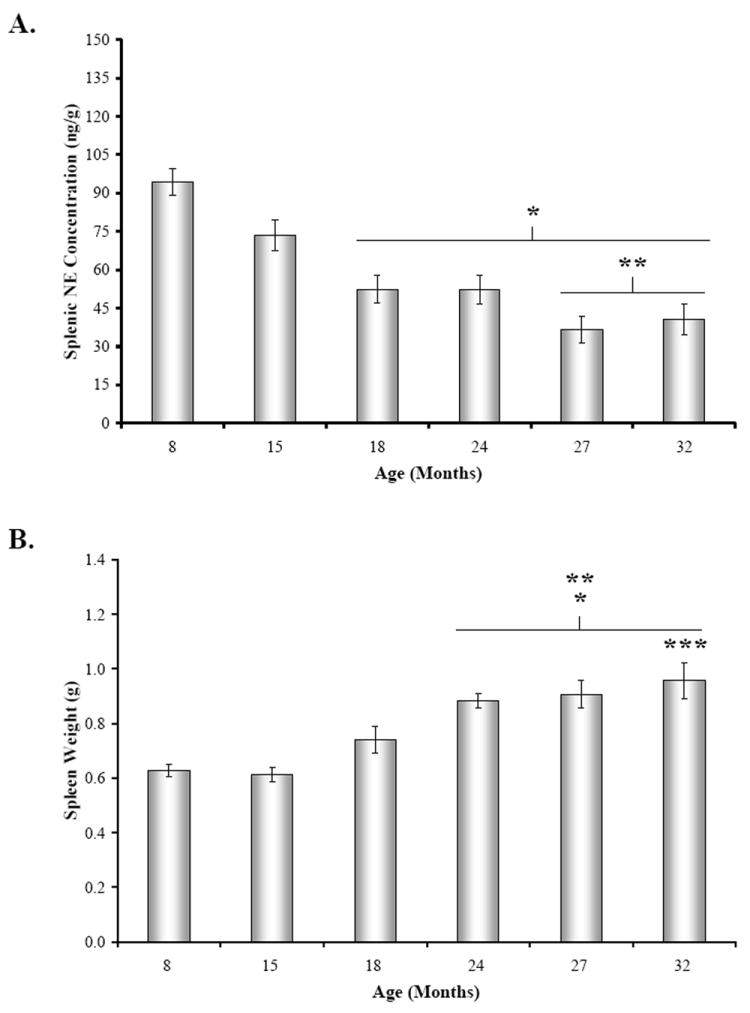

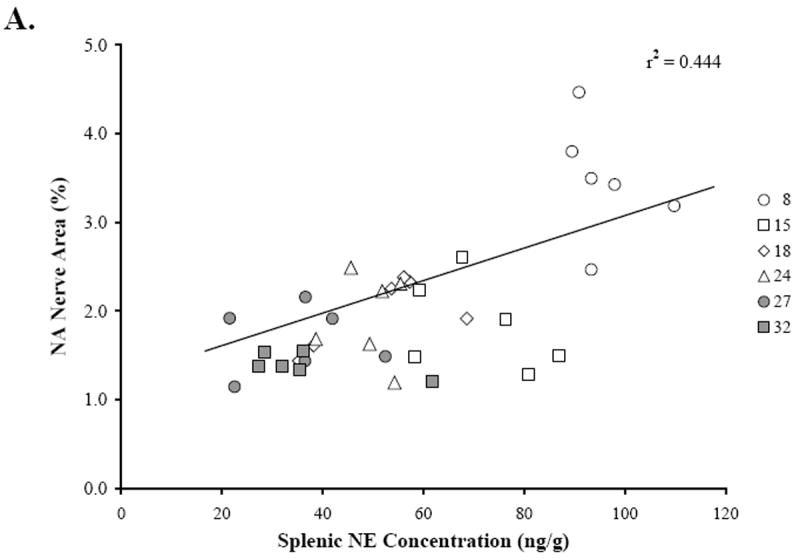

There was a significant effect of age on splenic NE concentration (Fig. 3A) (F(5,41)= 15.39, p < 0.0001). In 15M and 18M rats, the mean splenic NE concentration (Fig. 3A) was reduced by approximately 25 and 45% of the 8M values, respectively (only significant at 18M, p < 0.001), followed by a more gradual decline between 18 and 32 months of age (8 vs.24-32M, p < 0.001). Additionally, posthoc analysis also revealed a significant decrease in mean splenic NE concentration at 27 and 32 months of age compared with 15M rats (27M, p < 0.001; 32M, p < 0.01), representing approximately a 44% drop in splenic NE concentration from 15 to 32 months of age.

Fig. 3. Mean Concentrations Splenic NE, Spleen Weight, and Body Weight across Age.

A. Mean splenic norepinephrine (NE) concentration (expressed in ng/g tissue wet weight) was slightly lower, but not significantly different at 15 months of age compared with 8M rat. Between 18 and 32 months of age, splenic NE levels significantly (*, p < 0.001) decreased compared with 8M levels. Splenic NE concentrations from 27M and 32M rats also significantly differed (**, p < 0.01 and p < 0.01, respectively) from levels in 15M rats. B. Mean spleen weight (expressed in g) progressively rose between 8 and 32 months of age, with significant differences revealed by posthoc analysis in 24 through 32M rats compared with 8M and 15M rats (*, p < 0.01, 24M; p < 0.001, 27-32M and **, p < 0.001, respectively). Spleen weight also was significantly higher in 32M compared with 18M rats (***, p < 0.05). C. Mean body weights (expressed in g) were comparable at 8 and 15 months of age, but increased between 18 and 32 months of age. Error bars = SEM. *, significantly different from 8M: 18M, p < 0.01; 24 – 32M, p < 0.001; **, significantly different from 15M: 24 – 32M, p < 0.001; ***, significantly different from 18M: 24 – 27M, p < 0.001.

In contrast, the mean spleen weight progressively increased from 15 through 32 months of age (Fig. 3B) (F(5,41) = 12.67, p < 0.0001). Spleen weights from 24M, 27M, and 32M rats were significantly greater than 8M rats (24M, p < 0.01; 27-32M, p < 0.001). Similarly, spleens from 24-32M rats weighed significantly more than spleens from middle aged rats (15M vs. 24-32M, p < 0.001; 18M vs. 32M, p < 0.05). Similar to spleen weights, body weight progressively increased from 15 through 32 months of age (Fig. 3C).

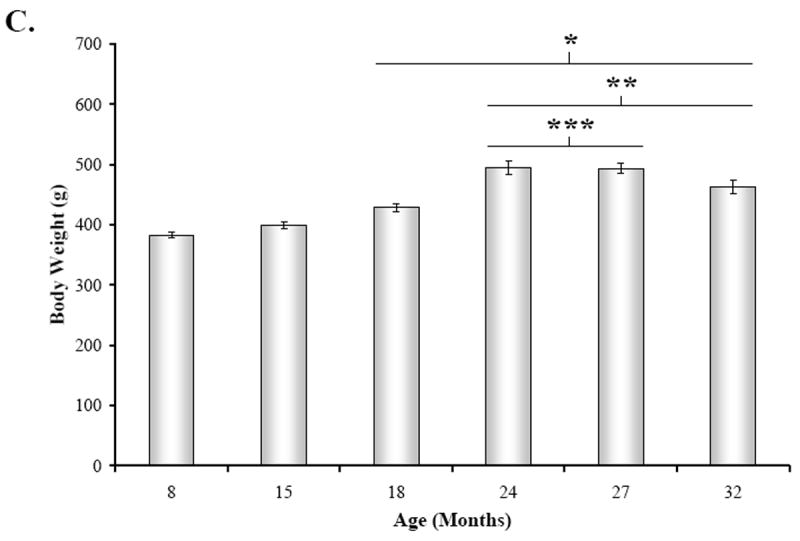

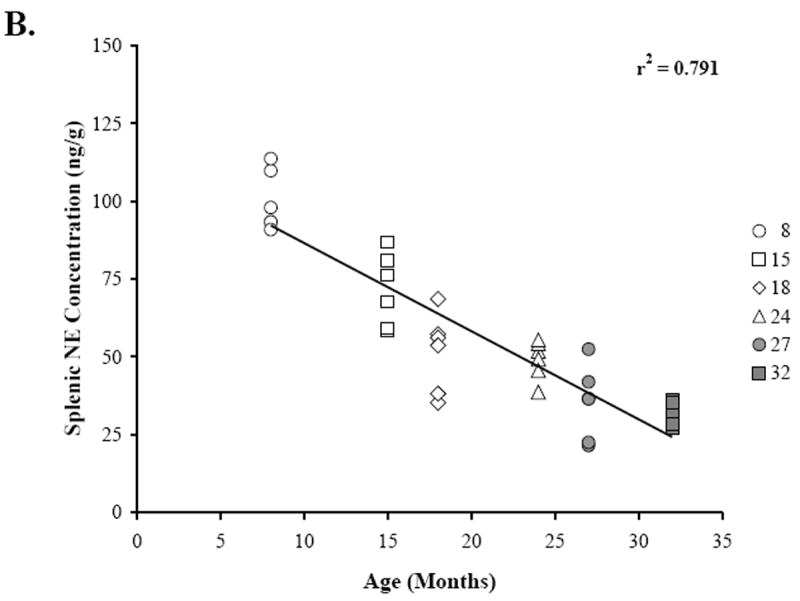

Figure 4 shows the scatter plots that demonstrate the relationships between splenic NE concentration (Fig. 4A, 4B), percentage of NA nerve area in the splenic white pulps (Fig. 4A), and age (Fig. 4B). Linear regression analysis revealed a positive correlation (r2 = 0.444; p < 0.0001) between splenic NE concentration and NA nerve area in the splenic white pulp. A higher percentage of sympathetic nerves in the white pulp is associated with greater splenic NE concentration (Fig. 4A). In contrast, increasing age is associated (r2 = 0.791; p < 0.0001) with reduced splenic NE concentration (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4. Relationship between Splenic NE Concentration and NA Nerve Area or Age.

The scatter plots demonstrate the distribution of the mean percentage of NA nerve area in the white pulps that were sampled per rat across splenic NE concentration (ng/g) for each age group (A), and the distribution of splenic NE concentration (ng/g) across age (B). Linear regression analysis was used to plot the line of best fit and calculate r2, and reveals a positive association (p < 0.0001) between NA nerve area in the white pulp and splenic NE concentration (A) and a negative correlation between splenic NE concentration and increasing age (p < 0.0001) (B).

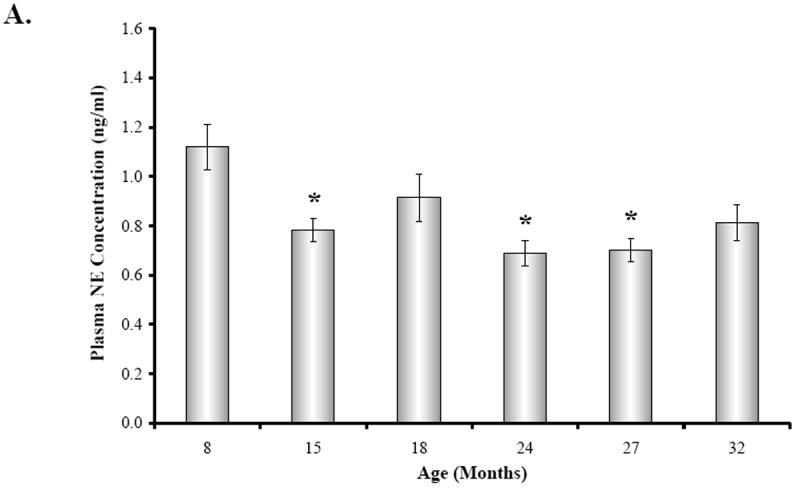

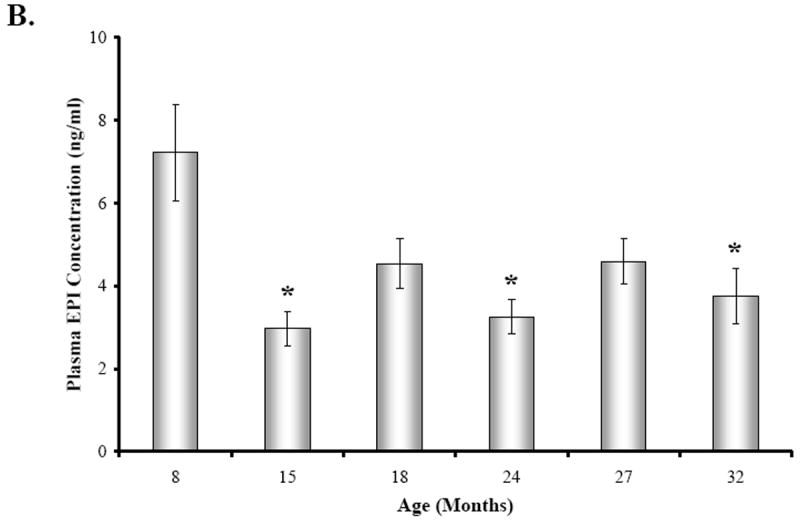

3.4. Mean Plasma Catecholamine Concentration

Plasma catecholamine levels in all age groups were significantly elevated over basal levels previously reported in the literature (Fig. 5A-B). There was an effect of age on mean plasma catecholamine levels (Fig. 5A-B) (NE, F(5,34) = 5.652, p < 0.0007; EPI, F(5,33) = 5.143, p < 0.0014). Mean plasma NE concentration (Fig. 5A) was reduced by approximately 24% in 15, 24, and 27M old rats compared with young adults (15M, p < 0.05; 24M, p < 0.001; 27M, p < 0.01). Similarly, plasma EPI levels (Fig. 5B) were highest at 8 months of age and reduced with aging (~32-58%), with a significant decline observed at 15, 24, and 32 months of age compared with young adult rats (15M, 24M, p < 0.01; 32M, p < 0.05).

Fig. 5. The Effect of Decapitation-Induced Stress on Plasma Catecholamine Content from Trunk Blood across Age.

Plasma norepinephrine (NE) (A) and epinephrine (EPI) (B) concentrations (expressed in ng/ml as a mean ± SEM) in BN rats are shown across age (in months). A. Plasma NE concentrations were significantly (*, p < 0.05, p < 0.001, and p < 0.01, respectively) diminished at 15, 24, and 27 months of age compared with 8M rats. B. Similarly, plasma EPI levels were significantly (*, p < 0.01, 15 and 24M; p < 0.05, 32M) lower at 15, 24, and 32 months of age compared with 8M rats. Dashed boxes represent the range of basal catecholamines levels reported in the literature based on assessments from awake, undisturbed rats from which blood was drawn via an indwelling catheter ((Popper et al., 1977; Mabry et al 1995a,b,c; Paulose and Dakshinamurti, 1987; Carruba et al., 1981; Kvetnansky et al., 1978).

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrated a dramatic age-related decline in NA sympathetic nerve density and NE concentration in spleens from male BN rats that was evident by early middle age (15M). Splenic NE concentration positively correlated with sympathetic nerve area. In contrast, both splenic NE concentration and sympathetic nerve area in the white pulp negatively correlated with age. These findings are consistent with a loss of neurotransmitter content in the spleen as sympathetic nerves are concomitantly lost with advancing age. NA nerve density in the splenic white pulp, as well as other splenic compartments, was relatively comparable between 15 and 32 months of age despite the progressive decline in splenic NE concentration during this time period. These findings suggest a dying back of sympathetic nerves in middle age without a change in NE metabolism. Furthermore, these results suggest that there are age-related alterations in sympathetic signaling to immune cells in the aging BN rat spleen, because the amount of NE that is available to interact with cells of the immune system is reduced.

These findings are generally consistent with reports in male F344 rats (Bellinger et al., 1987, 1992a,b), the most commonly used rat model for aging. Interestly, the age at which NA nerve loss becomes evident is comparable in both strains of rats (18 months of age) despite the fact that male BN rats live 20% longer than male F344 rats (75% mortality by 34 and 26 months of age, respectively (Nadon, 2004)). However, there are some noteworthy differences between these two strains. First, the decline in splenic nerve density in the white pulp is less extensive in BN compared with F344 rats (~56% vs. 75% at around the time of 75% mortality). This finding suggests that while the mechanisms that initiate the age-related decline in sympathetic innervation of the spleen may be similar in these two strains, the microenvironment of spleen may differ such that greater resilience is afforded to sympathetic nerve fibers in spleens from BN rats. Whether this is a reflection of the striking differences in the immune profiles of these two strains awaits further study. Similarly, how differential preservation of sympathetic innervation of secondary lymphoid tissues, and its consequences on immune regulation contributes to greater longevity, requires further investigation.

Another difference between these two strains is that the decline in nerve density in old BN rats is comparable to the loss of splenic NE concentration (approximately 56-57% decline for both parameters at 32 months of age). In contrast, the extent of NA nerve lost at 27 months of age in F344 rats is much greater (75%) than the loss in splenic NE concentration (~50%) (Bellinger et al., 1987, 1992b). These data, along with functional data in F344 rats indicating increased signaling of splenocytes via NE binding with β-AR (Bellinger et al., 2008a) suggest compensatory mechanisms in NE metabolism in response to NA nerve loss in F344 rats, which do not occur with nerve loss in BN rats. NE turnover studies are needed to directly address this hypothesis; however preliminary findings from our laboratory (unpublished observations) showing that NE signaling of splenocytes via β-AR stimulation is significantly impaired in old BN rats indirectly supports this hypothesis.

In a previous study from our laboratory (Bellinger et al., 2002) no significant differences in splenic NE concentration between 8M and 21M male BN rats were reported. The reason for the greater effect of aging on NA nerve integrity observed in the present study is not known, but may be due to differences in the vendor source. Male BN rats in the present study were obtained through National Institute on Aging (NIA) from Harlan, whereas in the earlier study animals were purchases through NIA from Charles River Laboratories. These discrepancies are not unique as other studies have reported differences in physiological parameters depending on the vendor source (Perrotti et al., 2001; Turnbull and Rivier, 1999; Pare and Kluczynski, 1997). For example, neuroendocrine and immune responses to inflammatory stimuli differed in Sprague-Dawley rats depending on whether they were obtained through Harlan or Charles Rivers Laboratories (Turnbull and Rivier, 1999).

The loss of NA innervation of the spleen in male BN rats may be explained by (a) changes in neurotrophic support, neurotrophic receptor expression, and/or neurotrophic signal transduction in splenic sympathetic NA nerve fibers, (b) cumulative effects of oxidative stress on the NA nerve fibers, and/or (c) an increase in systemic inflammation that occurs with aging. Neurotrophic growth factors such as neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) and nerve growth factor (NGF) are important for maintaining and supporting NA nerve integrity (Levi-Montalcini, 2004). NGF, NT-3 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor are abundantly present in the spleen (Yamamoto et al., 1996). While it is not known whether there is an age-related decrease in NGF activity in F344 and BN rats, there are reports of an age- and disease-related decline in the content of NGF in several organs. Nishizuka and coworkers reported a decline in NGF in specific brain regions with age (Nishizuka et al., 1991; Nitta et al., 1993). There is also a decline in NGF and NT3 in the spleens of Lewis rats with adjuvant-induced arthritis (Bellinger et al., 2001). NGF, an essential neurotrophin factor for sympathetic neuron survival, is extensively distributed in the parenchyma of spleen. A decline in its activity may explain the age-related disappearance of NA nerve fibers in splenic white pulp.

In support for a role for oxidative stress in NA nerve loss, administration of deprenyl, a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, reverses the 6-hydroxydopamine-induced and age-related loss of splenic NA innervation in young and old F344 rats respectively (reviewed in ThyagaRajan and Felten, 2002). The reversal in NA neuronal loss was accompanied by enhanced cell-mediated immunity especially NK cell activity and IL-2 and IFN-γ production (reviewed in ThyagaRajan and Felten, 2002). These studies suggest growth factors and cytokines are important in maintaining sympathetic nerve fibers in the splenic white pulp across life span, and altered trophic support can have functional consequences.

Alternatively, individual variability in aging of sympathetic innervation of the spleen, or survival selectivity may contribute to the differences seen; however, the individual variability we found in our study does not lend support to the former hypothesis. Other factors that may contribute include differences in animal transport to the study location, time of year, and housing conditions. Collectively, these findings suggest that environmental factors may affect NA nerve integrity in the aging rat spleen. In support of this hypothesis, Sloan et al (2008) have shown that simian immunodeficiency virus infection decreases sympathetic innervation of primate lymph nodes, possibly due to reduced neurotrophic support.

Plasma NE and EPI levels reported here reflect a stress response to handling and decapitation, as they are ~5-10 and 15-80 fold greater, respectively, than measurements taken via indwelling catheters from awake, undisturbed rats (Popper et al., 1977; Mabry et al 1995a,b,c; Paulose and Dakshinamurti, 1987; Carruba et al., 1981; Kvetnansky et al., 1978). Basal catecholamines were not measured in the present study, however, other studies in rats commonly report no effect of age on circulating NE and EPI (McCarty, 1981, 1985; Korte et al., 1992; Mabry et al., 1995a,b,c), and some studies have found elevated levels (Michalikova et al., 1990). Plasma NE and EPI concentrations from 8M rats in our study are comparable to levels previously reported in young BN rats (Gilad and Jimerson, 1981) and other rat strains under the conditions used to obtain blood in this study (Ben-Jonathan & Porter, 1976; Roizen et al., 1975; Popper et al., 1977). One study (Gilad and Jimerman, 1981) has compared sympathetic reactivity to decapitation stress alone or with immobilization in young BN and Wistar-Kyoto (WK) rats, of which the latter strain is more reactive to stress. They found that plasma catecholamine levels immediately after decapitation and 0 or 10 min after immobilization stress were significantly higher in WK than in BN rats. No studies that we are aware of have examined the effect of decapitation stress in the long-lived BN rat across age. However, in another study from our laboratory, no age-related change in decapitation stress-induced plasma NE concentrations and reduced plasma EPI levels at 24 months were found in male F344 rats (Bellinger et al., 2008a), a strain with a little less than 1 year shorter median life span (Nadon, 2004) and greater behavioral responses to stress generally attributed to differences in hypothalamic-adrenocortical functioning (Marissal-Arvy et al., 1999; Sarrieau et al., 1998; Gómez et al., 1996, 1998; Kusnecov et al., 1995). The age-related decline in decapitation-stress induced rise in plasma NE and EPI concentrations found in this study suggests diminished capacity of the SNS and SAM to effectively respond to an acute stressor in aging male BN rats. Relevant to the present study, Kusnecov et al. (1995) demonstrated significant differences in footshock stress during early diurnal and nocturnal periods of the day on T cell mitogen-induced lymphocyte proliferation and IL-6 response in male BN rats compared with three other strains of rats, including F344 rats.

Stress studies by other investigators (Mabry et al., 1995a,b,c; Cizza et al., 1995) have demonstrated variable age-related differences in SNS and SAM reactivity to other acute and chronic stressors, depending on the type, duration, and intensity of the stressor. For example, in contrast to our findings in F344 rats, Mabry and colleagues (1995a) reported greater plasma catecholamine responses in aged F344 rats (22M) and slower return to baseline after termination of the stressor than those of young adult rats (3M) after cold (20 and 25 °C) swim stress, but no aging difference when the water temperature was at 30 or 35 °C. In another aging study using Wistar rats (Michalíková et al., 1990), basal plasma catecholamines were elevated in 11 and 28M rats compared with young rats, and immobilization stress markedly increased plasma NE in 11M, but plasma NE and EPI was mildly elevated in 28M animals. Although poorly characterized in rats, stress-induced effects on sympathetic reactivity in humans are not attributable to differences in thermoregulatory mechanisms or kinetic factors, such as neuronal uptake or plasma clearance rates of catecholamines (Linares and Halter, 1987; Morrow et al., 1987; Poehlman et al., 1990; Stromberg et al., 1991). Since visceral organs contribute very little to plasma NE levels (reviewed in Bellinger et al., 1998), it seems unlikely that reduced SNS activity in the spleen contributes to the lower plasma catecholamine levels. Collectively, these studies indicate an age-related impairment in the ability of animals, including humans, to adapt to an ever-changing environment because of defects in hypothalamic regulation of SNS and SAM activity in aged animals. Thus, whereas basal levels of circulating hormones, like NE and EPI, are often not affected by aging, defects in neuroendocrine and autonomic regulation become unmasked when aged animals are exposed to acute stressors.

Our plasma catecholamine findings are relevant to sympathetic regulation of immune function in at least two ways. First, physical and psychosocial stressors can affect an immune function by elevating circulating stress hormones [Szelenyi and Vizi, 2007; Starkie et al., 2005; Moncek et al., 2003; Giovambattista et al., 2000; Condé et al., 1999; Hasko et al., 1995; Mujika et al., 2004; Brenner et al., 1998; Pederson et al., 1997; Pyne, 1994; Hinrichsen et al., 1992]. Second, exposure to environmental antigens is in and of itself a stressor, affecting the reactivity of the SNS and SAM (Sakata et al., 1994; Moncek et al., 2003; Giovambattista et al., 2000).

The functional significance of altered sympathetic reactivity to stress and sympathetic innervation of the aging rat spleen awaits further investigation. It is clear, at least in young adults, the SNS plays an important role in regulating immune function and that dysregulation of the SNS can affect immune-mediated diseases (reviewed in Kin and Sanders, 2006; Bellinger et al., 2008b; Elenkov et al., 2000). It is also well documented that as cell-mediated immunity declines with increasing age (reviewed in Chakravarti and Abraham, 1999; Shearer, 1997), there is a shift toward humoral-mediated immunity (Caruso et al., 1996; Castle et al., 1997). Given these data, it is tempting to speculate that altered NA neural signaling of the immune system may contribute to immune senescence. Whether this is true or not, SNS dysregulation in aging is likely to affect the host’s ability to optimally defend against infectious diseases, prevent autoimmunity, detect/eliminate cancerous cells, and influence circulating proinflammatory cytokine levels, which progressively rise with age. As the immune system shifts to a Th2 response with aging, tolerance mechanisms have been postulated to fail leading to the production of clinically significant autoreactive antibodies (Stacy et al., 2002; Stephan et al., 1997).

BN rats are unique, because they have a vigorous Th2 immune responses, producing cytokines IL-4, IL-6, and IL-10, along with antibody isotypes IgG1 and IgE on antigenic stimulation (Fournié et al., 2001). They also share many immunological and physical responses seen in human asthma, such as high production of IgE antibody, contraction of airway smooth muscle, airway hyperresponsiveness, involvement of leukotrienes in lung reactions, and infiltration of eosinophils and lymphocytes into the airway (Ohtsuka et al., 2005). BN rats are widely used to study several chemically-induced autoimmune syndromes such as polyarthritis, vasculitis, lupus-like syndromes, and other types of T helper cell dependent autoimmune diseases. With their striking Th2 bias, aged BN rats may provide a good model for discovering the mechanisms that predispose the elderly to increased risk for Th2-mediated autoimmune diseases and asthma. Careful analysis of species- and strain-related differences in how the SNS and immune system changes with advancing age and their relationship with frequencies of morbidity and mortality to certain types of disease may reveal risk factors and/or aging phenotypes that strongly predict susceptibility to certain types of diseases associated with aging.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

2.1. Animals

Male, inbred, specific-pathogen-free BN/Bi (BN) rats at 8, 15, 18, 24, 27, or 32 months of age (n of 8 per age group) were purchased under a National Institute of Aging (NIA) contract from Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, IN). Animals were housed two per cage in the vivarium at Loma Linda University, an Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (ALAC)-accredited facility. The room temperature (22-25 °C) and humidity (30-40%) were controlled and maintained on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. Rats had access to rodent chow and water ad libitum. Animals were closely observed for changes in physical condition and/or presence of age-related illness. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Loma Linda University. At the time of sacrifice, all visceral organs were autopsied for evidence of gross pathologies and tissues were dissected for study. Rats with any visible lesions, tumors, and evident pathology were removed from this study and their tissues excluded from the analysis. Three additional animals per group at older ages in our study were purchased to compensate for loss of animals from the study due to pathology and to maintain an n of 8 per treatment group.

2.2. Study Design

Rats were housed in the vivarium at Loma Linda University for 1 week prior to study initiation to acclimate to vivarium conditions. After acclimation to vivarium conditions, rats were sacrificed by decapitation, and spleens and trunk blood were immediately harvested. Spleens were cut cross-sectionally into 5 equally-sized pieces. The middle piece of the spleen was weighed, immediately frozen on dry ice, and stored at -80 °C until samples were prepared for neurochemical measurement of NE by high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection (HPLC). The adjacent spleen pieces were used for fluorescence histochemical staining to localize NA nerves. Trunk blood (8-10 ml per sample) was collected in 12×75 mm tubes containing 10 mmol/L disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) kept on ice. All blood samples were collected within 1 min of decapitation. After centrifugation (1200 rpm), the plasma was collected into microfuge tubes and stored at -80 °C until the determination of catecholamine levels.

2.3. Fluorescence Histochemistry for Catecholamines

The glyoxylic acid method of histofluorescence for catecholamines was used to visualize NA sympathetic nerves in spleens from BN rats. Spleen blocks from each rat were sectioned at 16 μm on a cryostat at -20 °C. The sections were thaw-mounted onto slides and stained using a modification of the glyoxylic acid condensation method (SPG method), as previously described by de la Torre (1980). Briefly, 3 sections were mounted on each slide, dipped into a solution containing 1% glyoxylic acid, 0.2 M potassium phosphate, and 0.2 M sucrose (pH 7.4), and then slides were air dried under a direct stream of cool air for 15 minutes. Spleen sections were covered with several drops of mineral oil, placed on a copper plate in an oven at 95 °C for 2.5 minutes, then coverslipped. Catecholamine-containing nerve terminals were visualized using an Olympus BH-2 fluorescence microscope equipped with epi-illumination accessories.

2.4 High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with Coulometric Detection

Spleen samples were transferred into labeled centrifuge tubes containing 10X volume per tissue wet weight of cold 0.1 M perchloric acid containing 0.25 μM 3, 4-dihydroxybenzylamine (DHBA) as an internal standard, sonicated using a Branson Sonifier 250, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. Supernatants were transferred to microfilterfuge tubes, centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min and stored at -80 °C until assayed for NE content. Plasma samples (200 μl per sample) were pipetted into a 12×75 mm glass tube, followed by the addition of 1.0 ml of phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 1.0 ml of 1.5 M Tris buffer (pH 8.6), 50 μl of the internal standard, DHBA, and 50 mg of acid washed alumina. Plasma samples were vortexed and placed on a shaker for 5 min at 175 rpm and then the alumina was allowed to settle. Next, the samples were aspirated, washed 3X with double distilled H2O, and centrifuged for 2 min at 14,000 rpm. The alumina was placed into a new microfilterfuge tube and vortexed in 200 μl of 0.1 M HClO4. After the samples were centrifuged again for 2 min at 9000 rpm, 50 μl of supernatant from each sample were transferred to HPLC vials and loaded into an ESA Model 542 autosampler to quantify NE concentrations ([NE]) by HPLC using a CouleChem HPLC System (ESA, Chelmsford, MA). The mobile phase was delivered at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min by an ESA Model 582 solvent delivery module through a reverse phase C18 5 μm, 8×100 mm Radial-Pak analytical column. The potential through the guard cell and the two detector cells in the ESA CouleChem III coulometric system were set at 400 mV, 350 mV, and -350 mV, respectively. Peak heights and area under the curves were analyzed using EZChrom Elite Software (Scientific Software Inc. Pleasanton, CA). Unknown sample catecholamine concentrations were determined by comparing peak area (peak height) with those from known standards.

2.6. Data Analysis

Morphometric analysis of splenic NA nerves in the white pulp was carried out without knowledge of the treatment groups (i.e., blinded) using the Image Pro® Plus software (version 5.0; Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD), as previously described (Lorton et al., 2005; Bellinger et al., 1987, 2002). The white pulp was selected for analysis, because the majority of sympathetic nerve fibers innervate this splenic compartment. One randomly selected splenic white pulp in the hilar region (the point of NA nerve entry into the spleen) of 4 spleen sections per rat from 6 animals per age group was used for analysis. The criteria for selection of white pulps for analysis were that (1) there was only one cross-section through the central arteriole in the white pulp; (2) the size of the central arteriole was comparable across all samples (80-100 μm across the largest diameter of the vessel) and (3) the arteriole was cut in true cross section. Splenic white pulps were digitally photographed at 200X and the number of pixels containing NA nerve profiles in each image, based on size and color, were determined. At this magnification, all pixels of each image were within the white pulp. The number of positive pixels (i.e., those containing nerve fibers) was used to determine the percentage of the total area positive for sympathetic nerves in each image. The average percentage area positive for sympathetic nerves from the 4 white pulps that were sampled from each animal was calculated, and then the means from each animal per age group were averaged to determine the within group mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM).

Catecholamine concentrations, and spleen and body weights were expressed as a mean ± SEM. NE concentrations in the spleen, and plasma NE and EPI concentrations, were determined from known standards and concentrations corrected based on the recovery rate of the internal standard, DHBA. Plasma catecholamineconcentrations were expressed in ng/ml. Splenic NE concentration was expressed in ng per g tissue wet weight. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on all data to determine between group differences using GraphPad Prism 4.0®. Factors reaching significance levels of at least p < 0.05 by ANOVA were subjected to Bonferroni post-hoc analysis to determine which groups contributed to the significant ANOVA. Scatter plots and least-squares linear regression analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.0® to determine correlations between splenic NE content and noradrenergic nerve density and age, and splenic NE concentration and age.Lines of best fit with a 95% confidence interval were generated. Significance levels were determined by calculating the correlation coefficients (r2 values) and degrees of freedom (n-2); p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH Grant NS44302.

Abbreviations

- DHBA

4-dihydroxybenzylamine

- AR

adrenergic receptors

- BN

Brown Norway

- BNF1

BN X F344 (F1)

- CNS

central nervous system

- DTH

delayed type hypersensitivity

- DP

diastolic pressure

- EPI

epinephrine

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- F344

Fischer 344

- SPG method

glyoxylic acid condensation method

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection

- IL

interleukin

- M

month-old

- NK

natural killer

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- NT-3

neurotrophin-3

- NZB, NZW, and NZBW

New Zealand black, white, and black and white mice, respectively

- NA

noradrenergic

- NE

norepinephrine

- PALS

periarteriolar lymphatic sheath

- HClO4

perchloric acid

- SAM

sympathetic-adrenal medullary system

- SNS

sympathetic nervous system

- Th1

T-helper-1

- Th2

T-helper-2

- WK

Wistar-Kyoto

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES CITED

- Bellinger DL, Silva D, Millar AB, Molinaro C, Ghamsary M, Carter J, Perez S, Lorton D, Lubahn C, Arauja G, Thyagarajan S. Sympathetic nervous system and lymphocyte proliferation in the Fischer 344 rat spleen: a longitudinal study. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2008a;15:260–271. doi: 10.1159/000156469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger DL, Millar BA, Perez S, Carter J, Wood C, Thyagarajan S, Molinaro C, Lubahn C, Lorton D. Sympathetic modulation of immunity: relevance to disease. Cell Immunol. 2008b;252:27–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger DL, Stevens SY, ThyagaRajan S, Lorton D, Madden KS. Aging and sympathetic modulation of immune function in Fischer 344 rats: effects of chemical sympathectomy on primary antibody response. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;165:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger D, Tran L, Kang J, Lubahn C, Felten D, Lorton D. Age-related changes in noradrenergic sympathetic innervation of the rat spleen are strain dependent. Brain Behav Immun. 2002;16:247–261. doi: 10.1006/brbi.2001.0626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger D, Lorton D, Lubahn C, Felten D. Innervation of lymphoid organs: association of nerves with cells of the immune system and their implications in disease. In: Ader R, Felten DL, Cohen N, editors. Psychoneuroimmunology. Academic Press; San Diego: 2001. pp. 55–111. [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger DL, Felten DL. Sympathetic nervous system and aging. In: Mobbs CV, Hov PF, editors. Interdiscipl Topics Gerontol, Functional Endocrinology of Aging. Vol. 29. Karger; Basel: 1998. pp. 166–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger DL, Lorton D, Felten SY, Felten DL. Innervation of lymphoid organs and implications in development, aging, and autoimmunity. Int J Immunopharmacol. 1992a;14:329–344. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(92)90162-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger DL, Ackerman KD, Felten SY, Felten DL. A longitudinal study of age-related loss of noradrenergic nerves and lymphoid cells in the rat spleen. Exp Neurol. 1992b;116:295–311. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(92)90009-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellinger DL, Felten SY, Collier TJ, Felten DL. Noradrenergic sympathetic innervation of the spleen: IV. Morphometric analysis in adult and aged F344 rats. J Neurosci Res. 1987;18:55–63. 126–129. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490180110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Jonathan N, Porter JC. A sensitive radioenzymatic assay for dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine in plasma and tissue. Endocrinology. 1976;98:1497–1507. doi: 10.1210/endo-98-6-1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishopric NH, Cohen HJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta adrenergic receptors in lymphocyte subpopulations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1980;65:29–33. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(80)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breneman SM, Moynihan JA, Grota LJ, Felten DL, Felten SY. Splenic norepinephrine is decreased in MRL-lpr/lpr mice. Brain Behav Immun. 1993;7:135–143. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1993.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner I, Shek PN, Zamecnik J, Shephard RJ. Stress hormones and the immunological responses to heat and exercise. Int J Sports Med. 1998;19:130–143. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunag RD, Teravainen TL. Tail-cuff detection of systolic hypertension in different strains of ageing rats. Mech Ageing Develop. 1991;59:197–213. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(91)90085-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruba MO, Picotti GB, Miodini P, Lotz W, Da Prada M. Blood sampling by chronic cannulation technique for reliable measurements of catecholamines and other hormones in plasma of conscious rats. J Pharmacol Methods. 1981;5:293–303. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(81)90041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso C, Candore G, Cigna D, DiLorenzo G, Sireci G, Dieli F, Salerno A. Cytokine production pathway in the elderly. Immunol Res. 1996;15:84–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02918286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle S, Uyemura K, Wong W, Modlin R, Effros R. Evidence of enhanced type 2 immune response and impaired upregulation of a type 1 response in frail elderly nursing home residents. Mech Ageing Dev. 1997;94:7–16. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(96)01821-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti B, Abraham GN. Aging and T-cell-mediated immunity. Mech Ageing Dev. 1999;108:183–206. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(99)00009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cizza G, Pacak K, Kvetnansky R, Palkovits M, Goldstein DS, Brady LS, Fukuhara K, Bergamini E, Kopin IJ, Blackman MR, et al. Decreased stress responsivity of central and peripheral catecholaminergic systems in aged 344/N Fischer rats. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1217–1224. doi: 10.1172/JCI117771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condé GL, Renshaw D, Zubelewicz B, Lightman SL, Harbuz MS. Central LPS-induced c-fos expression in the PVN and the A1/A2 brainstem noradrenergic cell groups is altered by adrenalectomy. Neuroendocrinology. 1999;70:175–185. doi: 10.1159/000054474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Torre J. Standardization of the sucrose-potassium phosphate-glyoxylic acid histofluorescence method for tissue monoamines. Neurosci Lett. 1980;17:339–340. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(80)90047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs CM, Vasquez M, Glaser R, Sheridan JF. Mechanisms of stress-induced modulation of viral pathogenesis and immunity. J Neuroimmunol. 1993;48:151–160. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(93)90187-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duclos M, Bouchet M, Vettier A, Richard D. Genetic differences in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity and food restriction-induced hyperactivity in three inbred strains of rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 2005;17:740–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2005.01367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov IJ, Wilder RL, Chrousos GP, Vizi ES. The sympathetic nerve—an integrative interface between two supersystems: the brain and the immune system. Pharmacol Rev. 2000;52:595–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festing MFW. Inbred strains of rats and their characteristics. Mouse Genome Informatics, The Jackson Laboratory. 1998 ( http://www.informatics.jax.org/external/festing/rat/docs/BN.shtml)

- Fournié GJ, Cautain B, Xystrakis E, Damoiseaux J, Mas M, Lagrange D, Bernard I, Subra JF, Pelletier L, Druet P, Saoudi A. Cellular and genetic factors involved in the difference between Brown-Norway and Lewis rats to develop respectively type-2 and type-1 immune-mediated diseases. Immunol Rev. 2001;184:145–160. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1840114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilad GM, Jimerson DC. Modes of adaptation of peripheral neuroendocrine mechanisms of the sympatho-adrenal system to short-term stress as studied in two inbred rat strains. Brain Res. 1981;206:83–93. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SC, Woda BA, Feldman JD. T lymphocytes of young and aged rats. I. Distribution, density, and capping of T antigens. J Immunol. 1981;127:149–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovambattista A, Chisari AN, Gaillard RC, Spinedi E. Modulatory role of the epinergic system in the neuroendocrine-immune system function. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2000;8:98–106. doi: 10.1159/000026459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez F, De Kloet ER, Armario A. Glucocorticoid negative feedback on the HPA axis in five inbred rat strains. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:R420–R427. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.274.2.R420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez F, Lahmame A, de Kloet ER, Armario A. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal response to chronic stress in five inbred rat strains: differential responses are mainly located at the adrenocortical level. Neuroendocrinology. 1996;63:327–337. doi: 10.1159/000126973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goonewardene IM, Murasko DM. Age associated changes in mitogen induced proliferation and cytokine production by lymphocytes of the long-lived brown Norway rat. Mech Ageing Dev. 1993;71:199–212. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(93)90084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruver AL, Hudson LL, Sempowski GD. Immunosenescence of aging. J Pathol. 2007;211:144–156. doi: 10.1002/path.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskó G, Elenkov IJ, Kvetan V, Vizi ES. Differential effect of selective block of alpha 2-adrenoreceptors on plasma levels of tumour necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-6 and corticosterone induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in mice. J Endocrinol. 1995;144:457–462. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1440457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichsen H, Fölsch U, Kirch W. Modulation of the immune response to stress in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: review of recent studies. Eur J Clin Invest. 1992;22(Suppl 1):21–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes DJ. Experimental Rodent Strains. Brown Norway Rat. Sci Aging Knowl Environ. 2004;2004:as3. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M, Hauger RL, Brown M, Britton KT. CRF activates autonomic nervous system and reduces natural killer cell cytotoxicity. Am J Physiol. 1988;255:R744–R747. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1988.255.5.R744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kin NW, Sanders VM. It takes nerve to tell T and B cells what to do. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;79:1093–104. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1105625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch C. Genetic control of antibody responses to PHA in inbred rats. Scand. J Immunol. 1976;5:1149–1153. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1976.tb00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohm AP, Sanders VM. Suppression of antigen-specific Th2 cell-dependent IgM and IgG1 production following norepinephrine depletion in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;162:5299–5308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korte SM, Buwalda B, Bouws GA, Koolhaas JM, Maes FW, Bohus B. Conditioned neuroendocrine and cardiovascular stress responsiveness accompanying behavioral passivity and activity in aged and in young rats. Physiol Behav. 1992;51:815–822. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(92)90120-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruszewska B, Felten SY, Moynihan JA. Alterations in cytokine and antibody production following chemical sympathectomy in two strains of mice. J Immunol. 1995;155:4613–4620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusnecov AW, Shurin MR, Armfield A, Litz J, Wood P, Zhou D, Rabin BS. Suppression of lymphocyte mitogenesis in different rat strains exposed to footshock during early diurnal and nocturnal time periods. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995;20:821–835. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvetnansky R, Sun CL, Lake CR, Thoa N, Torda T, Kopin IJ. Effect of handling and forced immobilization on rat plasma levels of epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. Endocrinology. 1978;103:1868–1874. doi: 10.1210/endo-103-5-1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurant P, Adrian M, Berthelot A. Effect of age on mechanical properties of rat mesenteric small arteries. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2004;82:269–275. doi: 10.1139/y04-026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Montalcini R. The nerve growth factor and the neuroscience chess board. Prog Brain Res. 2004;146:525–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Taylor S, Zegarelli B, Shen S, O’Rourke J, Cone RE. The induction of splenic suppressor T cells through an immune-privileged site requires an intact sympathetic nervous system. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;153:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linares OA, Halter JB. Sympathochromaffin system activity in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1987;35:448–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1987.tb04667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman RD, Dallal GE, Bronson RT. Effects of genotype and diet on age-related lesions in ad libitum fed and calorie-restricted F344, BN, and BNF3F1 rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1999;54:B478–B491. doi: 10.1093/gerona/54.11.b478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman RD, Chrisp CE, Hazzard DG, Bronson RT. Pathologic characterization of brown Norway, brown Norway × Fischer 344, and Fischer 344 × brown Norway rats with relation to age. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51:B54–B59. doi: 10.1093/gerona/51A.1.B54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorton D, Lubahn C, Sweeney S, Major A, Lindquist CA, Schaller J, Washington C, Bellinger DL. Differences in the injury/sprouting response of splenic noradrenergic nerves in Lewis rats with adjuvant-induced arthritis compared to rats treated with 6-hydroxydopamine. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorton D, Lubahn C, Lindquist CA, Schaller J, Washington C, Bellinger DL. Changes in the density and distribution of sympathetic nerves in spleens from Lewis rats with adjuvant-induced arthritis suggest that an injury and sprouting response occurs. J Comp Neurol. 2005;489:260–273. doi: 10.1002/cne.20640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabry TR, Gold PE, McCarty R. Age-related changes in plasma catecholamine and glucose responses of F-344 rats to a single footshock as used in inhibitory avoidance training. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1995c;64:146–155. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1995.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabry TR, Gold PE, McCarty R. Age-related changes in plasma catecholamine responses to chronic intermittent stress. Physiol Behav. 1995b;58:49–56. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(94)00387-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabry TR, Gold PE, McCarty R. Age-related changes in plasma catecholamine responses to acute swim stress. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1995a;63:260–268. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1995.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden KS, Bellinger DL, Felten SY, Snyder E, Maida ME, Felten DL. Alterations in sympathetic innervation of thymus and spleen in aged mice. Mech Ageing Dev. 1997;94:165–175. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(96)01858-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden KS, Sanders VM, Felten DL. Catecholamine influences and sympathetic neural modulation of immune responsiveness. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;35:417–448. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.002221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden KS, Felten SY, Felten DL, Sundaresan PR, Livnat S. Sympathetic neural modulation of the immune system. I. Depression of T cell immunity in vivo and in vitro following chemical sympathectomy. Brain Behav Immun. 1989;3:72–89. doi: 10.1016/0889-1591(89)90007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marissal-Arvy N, Mormède P, Sarrieau A. Strain differences in corticosteroid receptor efficiencies and regulation in Brown Norway and Fischer 344 rats. J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11:267–273. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marque V, Kieffer P, Atkinson J, Lartaud-Idjouadiene I. Elastic properties and composition of the aortic wall in old spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1999;34:415–422. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty R. Aged rats: diminished sympathetic-adrenal medullary responses to acute stress. Behav Neural Biol. 1981;33:204–212. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(81)91638-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty R. Sympathetic-adrenal medullary and cardiovascular responses to acute cold stress in adult and aged rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1985;12:15–22. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(85)90037-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalíková S, Balázová H, Jezová D, Kvetnanský R. Changes in circulating catecholamine levels in old rats under basal conditions and during stress. Bratisl Lek Listy. 1990;91:689–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncek F, Aguilera G, Jezova D. Insufficient activation of adrenocortical but not adrenomedullary hormones during stress in rats subjected to repeated immune challenge. J Neuroimmunol. 2003;142:86–92. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(03)00268-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrow LA, Linares OA, Hill TJ, Sanfield JA, Supiano MA, Rosen SG, Halter JB. Age differences in the plasma clearance mechanisms for epinephrine and norepinephrine in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;65:508–511. doi: 10.1210/jcem-65-3-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujika I, Padilla S, Pyne D, Busso T. Physiological changes associated with the pre-event taper in athletes. Sports Med. 2004;34:891–927. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434130-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadon NL. Gerontology and age-associated lesions. In: Suckow MA, Weisbroth SH, Franklin CL, editors. The Laboratory Rat. Academic Press; New York: 2006. pp. 761–772. [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka M, Katoh-Semba R, Eto K, Arai Y, Iizuka R, Kato K. Age- and sex-related differences in nerve growth factor distribution in the rat brain. Brain Res Bull. 1991;27:685–688. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90045-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta A, Hasegawa T, Nabeshima T. Oral administration of idebenone, a stimulator of NGF synthesis, recovers NGF content in aged rat brain. Neurosci Lett. 1993;163:219–222. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90387-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka R, Shutoh Y, Fujie H, Yamaguchi S, Takeda M, Harada T, Doi K. Changes in histology and expression of cytokines and chemokines in the rat lung following exposure to ovalbumin. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2005;56:361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pare WP, Kluczynski J. Differences in the stress response of Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) rats from different vendors. Physiol Behav. 1997;62:643–648. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulose CS, Dakshinamurti K. Chronic catheterization using vascular-access-port in rats: blood sampling with minimal stress for plasma catecholamine determination. J Neurosci Methods. 1987;22:141–146. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(87)90008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen BK, Bruunsgaard H, Klokker M, Kappel M, MacLean DA, Nielsen HB, Rohde T, Ullum H, Zacho M. Exercise-induced immunomodulation—possible roles of neuroendocrine and metabolic factors. Int J Sports Med. 1997;18(Suppl 1):S2–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotti LI, Russo SJ, Lagos F, Quinones-Jenab V. Vendor differences in cocaine-induced behavioral activity and hormonal interactions in ovariectomized Fischer rats. Brain Res Bull. 2001;54:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(00)00330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poehlman ET, McAuliffe T, Danforth E., Jr Effects of age and level of physical activity on plasma norepinephrine kinetics. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:E256–262. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1990.258.2.E256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popper CW, Chiueh CC, Kopin IJ. Plasma catecholamine concentrations in unanesthetized rats during sleep, wakefulness, immobilization and after decapitation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1977;202:144–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne DB. Regulation of neutrophil function during exercise. Sports Med. 1994;17:245–258. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199417040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell ES, Gattone VH., 2nd Immune system of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. I. Sympathetic innervation. Exp Neurol. 1992;117:44–50. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(92)90109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos A, Berton O, Mormède P, Chaouloff F. A multiple-test study of anxiety-related behaviours in six inbred rat strains. Behav Brain Res. 1997;85:57–69. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(96)00164-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex A, Sondern U, Voigt JP, Franck S, Fink H. Strain differences in fear-motivated behavior of rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;54:107–111. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roizen MF, Moss J, Henry DP, Weise V, Kopin IJ. Effect of general anesthetics on handling- and decapitation-induced increases in sympathoadrenal discharge. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1978;204:11–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sado Y, Naito I, Akita M, Okigaki T. Strain specific responses of inbred rats on the severity of experimental autoimmune glomerulonephritis. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1986;19:193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata Y, Morimoto A, Murakami N. Changes in plasma catecholamines during fever induced by bacterial endotoxin and interleukin-1 beta. Jpn J Physiol. 1994;44:693–703. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.44.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders VM, Munson AE. Beta adrenoceptor mediation of the enhancing effect of norepinephrine on the murine primary antibody response in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984;230:183–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders VM, Baker RA, Ramer-Quinn DS, Kasprowicz DJ, Fuchs BA, Street NE. Differential expression of the β2-adrenergic receptor by Th1 and Th2 clones. J Immunol. 1997;158:4200–4210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarrieau A, Chaouloff F, Lemaire V, Mormède P. Comparison of the neuroendocrine responses to stress in outbred, inbred and F1 hybrid rats. Life Sci. 1998;63:87–96. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segar TM, Kasckow JW, Welge JA, Herman JP. Heterogeneity of neuroendocrine stress responses in aging rat strains. Physiol Behav. 2009;96:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearer GM. Th1/Th2 changes in aging. Mech Aging Dev. 1997;94:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(96)01849-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan EK, Capitanio JP, Tarara RP, Mendoza SP, Mason WA, Cole SW. Social stress enhances sympathetic innervation of primate lymph nodes: mechanisms and implications for viral pathogenesis. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8857–8865. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1247-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan EK, Nguygen CT, Cox BF, Tarara RP, Capitanio JP, Cole SW. SIV infection decreases sympathetic innervation of primate lymph nodes: the role of neurotrophins. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy S, Krolick KA, Infante AJ, Kraig E. Immunological memory and late onset autoimmunity. Mech Ageing Dev. 2002;123:975–985. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(02)00035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan RP, Lill-Elghanian DA, Witte PL. Development of B cells in aged mice: decline in the ability of pro-B cells to respond to IL-7 but not to other growth factors. J Immunol. 1997;158:1598–1609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankus RP, Leslie GA. Rat interstrain antibody response and cross idiotypic specificity. Immunogenet. 1976;3:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Starkie RL, Hargreaves M, Rolland J, Febbraio MA. Heat stress, cytokines, and the immune response to exercise. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:404–412. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromberg JS, Linares OA, Supiano MA, Smith MJ, Foster AH, Halter JB. Effect of desipramine on norepinephrine metabolism in humans: interaction with aging. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:R1484–R1490. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.261.6.R1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szelényi J, Vizi ES. The catecholamine cytokine balance: interaction between the brain and the immune system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1113:311–324. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J, Bertrand H, Stacy C, Herlihy JT. Long-term caloric restriction improves baroreflex sensitivity in aging Fischer 344 rats. J Gerontol. 1993;48:B151–B155. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.4.b151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ThyagaRajan S, Felten DL. Modulation of neuroendocrine–immune signaling by L-deprenyl and L-desmethyldeprenyl in aging and mammary cancer. Mech Ageing Dev. 2002;123:1065–1079. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(01)00390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull AV, Rivier CL. Sprague-Dawley rats obtained from different vendors exhibit distinct adrenocorticotropin responses to inflammatory stimuli. Neuroendocrinology. 1999;70:186–195. doi: 10.1159/000054475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Staay FJ, Blokland A. Behavioral differences between outbred Wistar, inbred Fischer 344, Brown Norway, and hybrid Fischer 344 × Brown Norway rats. Physiol Behav. 1996;60:97–109. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizi ES, Elenkov IJ. Nonsynaptic noradrenaline release in neuro-immune responses. Acta Biol Hung. 2002;53:229–244. doi: 10.1556/ABiol.53.2002.1-2.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Sobue G, Yamamoto K, Terao S, Mitsuma T. Expression of mRNAs for neurotrophic factors (NGF, BDNF, NT-3, and GDNF) and their receptors (p75NGFR, trkA, trkB, and trkC) in the adult human peripheral nervous system and nonneural tissues. Neurochem Res. 1996;21:929–938. doi: 10.1007/BF02532343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Wang L, Huang C. Plasticity of GAP-43 innervation of the spleen during immune response in the mouse. Evidence for axonal sprouting and redistribution of the nerve fibers. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1998;5:53–60. doi: 10.1159/000026326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]