Abstract

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty is frequently used in patients with severe arterial narrowing due to atherosclerosis. However, it induces severe arterial injury and an inflammatory response leading to restenosis. Here, we studied a potential activation of the endocannabinoid system and the effect of FA amide hydrolase (FAAH) deficiency, the major enzyme responsible for endocannabinoid anandamide degradation, in arterial injury. We performed carotid balloon injury in atherosclerosis-prone apoE knockout (apoE−/−) and apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice. Anandamide levels were systemically elevated in apoE−/− mice after balloon injury. ApoE−/−FAAH−/− mice had significantly higher baseline anandamide levels and enhanced neointima formation compared with apoE−/− controls. The latter effect was inhibited by treatment with CB1 antagonist AM281. Similarly, apoE−/− mice treated with AM281 had reduced neointimal areas, reduced lesional vascular smooth-muscle cell (SMC) content, and proliferating cell counts. The lesional macrophage content was unchanged. In vitro proliferation rates were significantly reduced in CB1−/− SMCs or when treating apoE−/− or apoE−/−FAAH−/− SMCs with AM281. Macrophage in vitro adhesion and migration were marginally affected by CB1 deficiency. Reendothelialization was not inhibited by treatment with AM281. In conclusion, endogenous CB1 activation contributes to vascular SMC proliferation and neointima formation in response to arterial injury.

Keywords: restenosis, balloon injury, fatty acid amide hydrolase

Catheter-based balloon dilatation of stenotic arteries is a frequent intervention in patients with coronary or peripheral artery disease (1, 2). Despite its beneficial effects in improving blood flow, it leads to vascular injury, loss of endothelium, and subsequent platelet deposition (3). Together with leukocytes that are recruited to the site of vascular injury in response to chemokine release (4), platelets synthesize growth factors and proinflammatory cytokines (3). Vascular injury also induces medial smooth-muscle cell (SMC) apoptosis and subsequent proliferation of neighboring SMCs, followed by migration of a subpopulation of medial SMCs into the intima in response to platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) or other stimuli (5). Intimal SMCs further proliferate and undergo phenotypic changes (6). Current therapeutic strategies to block vascular SMC proliferation are based on drug-eluting stents releasing anti-proliferative agents such as sirolimus or paclitaxel. However, a major complication of these drug-eluting stents is delayed endothelial healing and in-stent-thrombosis, due to inhibitory effects of these drugs on the reendothelialization process and pro-thrombotic properties (7–9).

In recent years, the endocannabinoid system, an endogenous lipid signaling system, has gained interest as a potential therapeutic target for various disorders, including cardiovascular disease (10). The classic cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2 belong to the family of seven trans-membrane G-protein-coupled receptors. They are part of the endocannabinoid system, which further comprises endogenous ligands (endocannabinoids) and enzymes implicated in the synthesis and metabolism of endocannabinoids. One of the key enzymes is FA amide hydrolase (FAAH), responsible for the degradation of the endocannabinoid anandamide (11). Anandamide binds marginally more readily to CB1 than to CB2 receptors and exhibits lower CB2 than CB1 efficacy (12). In addition, FAAH is also partly responsible for the metabolism of other N-acylethanolamines, i.e., palmitoylethanolamide (PEA) and oleoylethanolamide (OEA), which activate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-α (PPAR-α) (13, 14).

Within the vascular system, CB1 and CB2 are expressed on endothelial and smooth-muscle cells, as well as immune cells (10). In vitro studies have demonstrated that both CB1 and CB2 affect vascular SMC proliferation and migration. In particular, activation of CB2 with synthetic ligands or blockade of CB1 signaling was found to inhibit SMC inflammatory responses (15, 16). In support of a potential relevance for restenosis prevention, we found that in vivo administration of CB2 agonists reduced neointima formation in a mouse model of balloon injury (17). The underlying mechanisms of CB2-mediated protection involved inhibitory effects on macrophage and SMC inflammatory responses. The in vivo role of CB1 and potential elevation of endocannabinoid levels in restenosis has not been investigated so far. A major limitation for in vivo studies of endocannabinoid effects is their rapid metabolism. To overcome this problem, mice lacking the major anandamide-degrading enzyme FAAH have been developed. These mice have strongly increased anandamide levels, in particular in brain and liver, confirming the key role of FAAH in anandamide degradation (11, 18). We recently demonstrated that FAAH deficiency in atherosclerosis-prone mice leads to the development of an unstable atherosclerotic plaque phenotype due to enhanced neutrophil recruitment (19).

In the present study, we focused on the role of endocannabinoid signaling in restenosis. In particular, we investigated a potential activation of the endocannabinoid system in response to balloon-induced arterial injury. We further studied the consequence of enhanced anandamide levels in FAAH-deficient mice as well as of pharmacological CB1 blockade on neointima formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse model of balloon-induced arterial injury

FAAH−/− mice in a C57BL/6J background (11) were backcrossed with apoE−/− mice to generate apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice as described (19). We used 10 week-old male apoE−/− and apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice that we fed with a high-cholesterol diet (1.25% cholesterol) for 8 weeks before and up to 4 weeks after balloon injury until euthanasia. In some experiments, apoE−/− and apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice were treated with the CB1 receptor antagonist AM281 (10 mg/kg/day intraperitoneally; Tocris) or vehicle (Tocrisolve, Tocris), with the first injection given 30 min before balloon injury, followed by daily administration until euthanasia. Seven days before balloon injury, mice received aspirin via drinking water (16 mg/kg/day) to prevent acute thrombus formation. Balloon distension injury of the left common carotid arteries was performed as described previously (17, 20) after anesthesia with xylazine (10 mg/kg) and ketamine (100 mg/kg). Controlled over-distension of the vessel was achieved using a mean balloon diameter of 0.79 mm for a 25 g mouse (Schwager Medica, Switzerland). The balloon was expanded using a water-filled inflation syringe with digital display (IntelliSystemMonitor II; Meritmedical, UT). All animal studies were approved by the local Ethics Committee and Federal Veterinary Office and correspond to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the United States National Institutes of Health.

Endocannabinoid measurement

Endocannabinoids were extracted from 100 μl of mouse serum by liquid-liquid extraction. Analyses were performed on an LC-MS/MS system consisting of an Ultimate 3000 RS (Dionex, CA) LC system and a 5500 QTrap triple quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer equipped with a TurboIon-Spray interface (AB Sciex; ON, Canada). Data acquisition and analysis were performed using Analyst software version 1.5.1 (AB Sciex) (21).

Blood analysis

For measurements of differential blood cell counts (hematocytometer; Sysmex Digitana AG) and serum endocannabinoid and cholesterol content, blood samples were collected at endpoints by cardiac puncture.

Cholesterol measurement

Three pools of serum (from two mice per pool) were used per group of mice. In each pool, total cholesterol concentration was measured using an enzymatic colorimetric assay (BioMérieux, France). Then, lipoproteins were separated by fast protein liquid chromatography by gel filtration onto a Superose 6 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) with online cholesterol determination. Optical density measured at the appropriate wavelength was automatically converted to a graphic signal representing the lipid distribution profile. The area under each peak is proportional to lipid concentration in each fraction, allowing determination of cholesterol concentration in VLDL, LDL, and HDL lipoprotein fractions.

Histological and morphometric analysis

Mice were euthanized 7 or 28 days after balloon distension injury following anesthesia with xylazine (10 mg/kg) and ketamine (100 mg/kg) to harvest the injured left and the untouched right common carotid artery. For histomorphological and immunohistochemical analyses, vessels were rinsed with normal saline, perfusion-fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), followed by 2 h post fixation in 4% PFA and overnight immersion in 30% sucrose. Then vessels were embedded in OCT compound (Tissue-Tek; Sakura, The Netherlands) and snap-frozen.

We performed Evans-blue staining of elastic laminae and DAPI staining of nuclei using three serial cross-sections (5 μm thickness, 300 μm distance) taken from the mid portion of dilated vessels. Van Gieson staining of perfusion-fixed frozen sections was carried out with the Accustain elastic stain kit (Sigma-Aldrich) for morphometric assessment of intimal, medial, and lumen area and external elastic lamina (EEL) circumference. Immunostaining was performed with monoclonal antibodies for mouse CD68 (AbD serotec) and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA, Thermo Scientific) or polyclonal antibodies for CB1 (abcam) and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA; Thermo Scientific). Specificity of CB1 immunostaining was confirmed by absence of immunosignal after preabsorption with CB1 blocking peptide (abcam). Quantifications were performed by computer image analysis using MetaMorph6 software (Zeiss).

SMC isolation and proliferation

Primary vascular SMCs from thoracoabdominal aortas of apoE−/−, apoE−/−FAAH−/−, CB1−/− (22), and wild-type (WT; C57BL/6) mice were obtained by enzymatic digestion as described (17). Freshly isolated cells were stimulated with 25 ng/ml PDGF-BB (R and D Systems) in the presence or absence of the CB1 antagonist AM281 (10 µM) to determine cell proliferation based on bromodeoxyuridine incorporation (Cell Proliferation ELISA; Roche).

Bone marrow-derived macrophage migration and adhesion assay

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) from CB1−/− or WT mice were isolated by flushing femurs and tibiae. Cells were cultured in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium Invitrogen) containing 30% L929-conditioned medium as a source of macrophage colony-stimulating factor as described (17). Chemotaxis to 50 ng/ml MCP-5 (CCL12; AbD Serotec) was assessed in a 48-well microchemotaxis-modified Boyden chamber (NeuroProbe; Gaithersburg, MD). Cells were counted at 1,000× magnification in five random oil-immersion fields, and the chemotaxis index was calculated from the number of cells migrated to the chemoattractant divided by the number of cells migrated to the medium. Adhesion to 96-well plates coated with 1 µg per well fibronectin (Sigma) was assessed with 5 × 104 carboxyfluorescein diacetate, succinimidyl ester-labeled (Molecular Probes) BMDMs per well. After incubation for 30 min, nonadherent cells were removed by PBS washes, and relative numbers of adherent cells were determined by fluorescence reading (Victor3 multilabel reader; PerkinElmer).

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as mean (±SEM). Differences between P values below 0.05 were considered significant. For all experiments, two-group comparisons were performed with GraphPad Prism 5.01 software using unpaired t-test or Mann-Whitney U test when equal variance test failed. For multiple-group comparison, one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post test was used.

RESULTS

Balloon injury increases systemic endocannabinoid levels and arterial CB1 expression

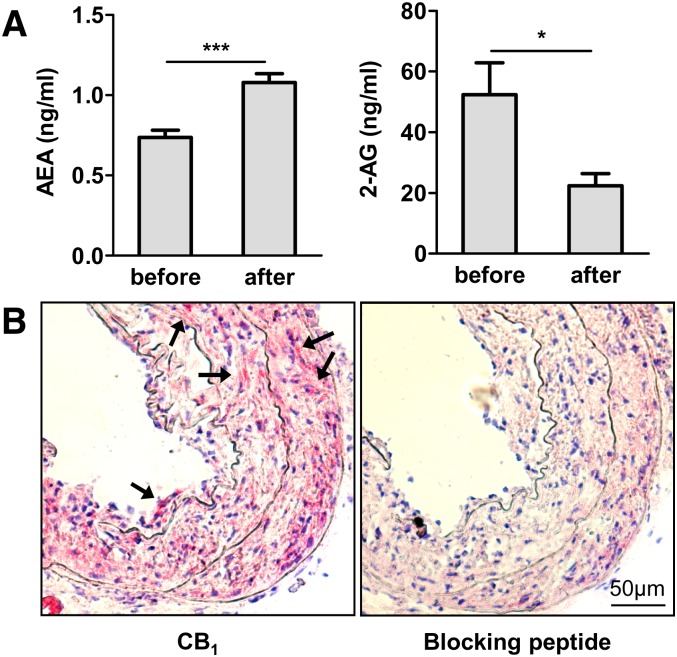

We tested a potential activation of the endocannabinoid system in response to balloon-induced arterial injury and found systemically elevated endocannabinoid anandamide levels in apoE−/− mice 7 days after balloon injury (Fig. 1A, P < 0.005). Surprisingly, endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) levels were 2.3-fold lower in response to balloon injury (P < 0.05). Although the CB1 receptor was undetectable in healthy control vessels, immunostaining revealed marked CB1 receptor expression in neointimal lesions of apoE−/− mice (Fig. 1B), suggesting an upregulation of CB1 receptor expression in response to injury. The specificity of the CB1 antibody was confirmed by preabsorption with blocking peptide before immunostaining.

Fig. 1.

Ballooning increases systemic endocannabinoid levels and arterial CB1 expression in hypercholesterolemic apoE−/− mice. A: Serum levels of endocannabinoids anandamide and 2-AG before and 7 days postinjury in apoE−/− mice (n = 6, ***P < 0.005). B: CB1 immunostaining in dilated carotid artery 28 days postballooning and negative control with blocking peptide. Stained cells are highlighted by arrows. 20× magnification.

Genetic deficiency of anandamide-metabolizing enzyme FAAH increases neointima formation

To clarify the causal effect of increased systemic anandamide levels in response to arterial injury, we investigated the effect of anandamide-degrading enzyme FAAH deficiency on neointima formation. At baseline, apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice exhibited significantly 1.8-fold increased serum anandamide levels in comparison to apoE−/− controls (Table 1; P < 0.005); however, anandamide levels did not further increase in FAAH-deficient mice in response to arterial injury. In addition, the levels of related FAAH substrates PEA and OEA were 2-fold higher in apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice compared with apoE−/− mice (P < 0.005). Interestingly, their serum levels significantly increased 1.5- to 2-fold in apoE−/− mice in response to balloon injury, comparable to the changes observed in anandamide levels (P < 0.005). Conversely, 2-AG levels were 2.3-fold lower (P < 0.01) in apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice after balloon injury, as observed in apoE−/− mice.

TABLE 1.

Serum endocannabinoid levels of apoE−/− versus apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice before and after arterial injury

| ApoE−/− | ApoE−/−FAAH−/− | ApoE−/− | ApoE−/−FAAH−/− | |

| Time point (ng/ml) | before | before | 7 days | 7 days |

| AEA | 0.737 ± 0.045 | 1.330 ± 0.044e | 1.078 ± 0.056c | 1.470 ± 0.215e |

| PEA | 7.202 ± 0.613 | 16.78 ± 0.778e | 11.04 ± 0.505c | 16.06 ± 1.671d |

| OEA | 5.228 ± 0.539 | 11.19 ± 0.243e | 10.86 ± 1.052c | 15.59 ± 0.643cd |

| 2-AG | 52.37 ± 10.45 | 56.39 ± 5.466 | 22.38 ± 3.999a | 24.65 ± 4.249b |

| n | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. AEA, anandamide; 2-AG, 2.arachidonylglycerol.

P < 0.05 for comparison of the same genotype at different time points.

P < 0.01 for comparison of the same genotype at different time points.

P < 0.005 for comparison of the same genotype at different time points.

P < 0.01 for comparison between two genotypes at the same time point.

P < 0.005 for comparison between two genotypes at the same time point.

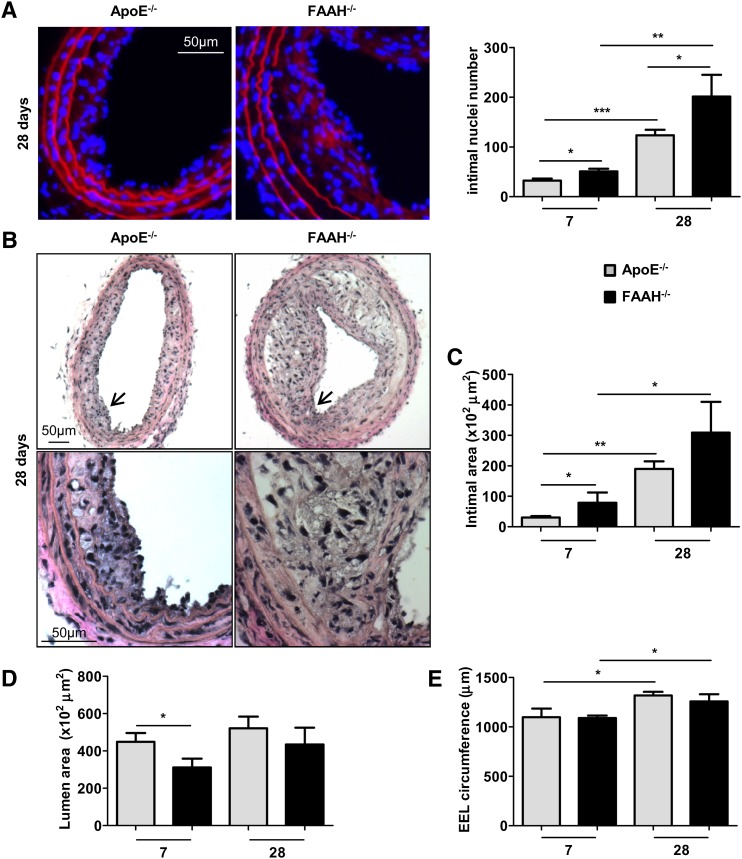

We found significantly increased intimal cell numbers in arteries of apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice 7 to 28 days postinjury compared with the apoE−/− control group (Fig. 2A, P < 0.05). Similarly, the morphometric analysis revealed significantly increased intimal areas in apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice (Fig. 2B, C, P < 0.05 after 7 days), whereas lumen areas were decreased (Fig. 2B, D, P < 0.05 after 7 days). After 28 days, the EEL circumference was significantly increased in both groups due to outward remodeling (Fig. 2E, P < 0.05). Of note, there was no difference in body weight and circulating leukocyte counts between the genotypes (Table 2), but a significantly lower LDL and HDL cholesterol content in apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice (Table 3, P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

FAAH deficiency increases neointima formation in hypercholesterolemic mice. A: Evans Blue (red)/DAPI (blue) staining of apoE−/− (gray bars) and apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice (black bars) 7 and 28 days postballooning was performed to visualize elastic laminae and nuclei. Intimal nuclei per entire cross-section were counted (n = 5–6). B–E: Van Gieson staining and morphometric analysis (n = 5–6). 10×, 40× magnification. Higher magnification zones are indicated by arrowheads. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005 for two-group comparison.

TABLE 2.

Systemic parameters of study groups 28 days postballooning

| ApoE−/− | ApoE−/−FAAH−/− | ApoE−/− | ApoE−/− | ApoE−/−FAAH−/− | ApoE−/−FAAH−/− | |

| Treatment | — | — | Vehicle | AM281 | Vehicle | AM281 |

| Body weight (g) | 29.14 ± 1.013 | 28.73 ± 1.462 | 29.18 ± 1.52 | 28.05 ± 0.96 | 25.62 ± 0.63 | 24.42 ± 0.29 |

| Leukocytes (n/µl) | 5340 ± 601.3 | 4517 ± 464.3 | 2.917 ± 293 | 3.450 ± 457 | 4.383 ± 511 | 3.520 ± 414 |

| n | 5 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

TABLE 3.

Cholesterol concentrations in the different study groups

| ApoE−/− | ApoE−/−FAAH−/− | ApoE−/− | ApoE−/− | ApoE−/−FAAH−/− | ApoE−/−FAAH−/− | |

| Treatment mg/dl | — | — | Vehicle | AM281 | Vehicle | AM281 |

| Total cholesterol | 735 ± 88 | 515 ± 15 | 847 ± 112 | 884 ± 71 | 714 ± 56 | 878 ± 151 |

| VLDL cholesterol | 396 ± 56 | 290 ± 14 | 482 ± 64 | 512 ± 63 | 396 ± 30 | 503 ± 88 |

| LDL cholesterol | 272 ± 28 | 181 ± 1a | 303 ± 46 | 308 ± 8 | 247 ± 14 | 307 ± 58 |

| HDL cholesterol | 66 ± 5 | 44 ± 5a | 62 ± 4 | 64 ± 3 | 71 ± 14 | 68 ± 7 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 3 per pool group (from two mice per pool).

P < 0.05 versus apoE−/−.

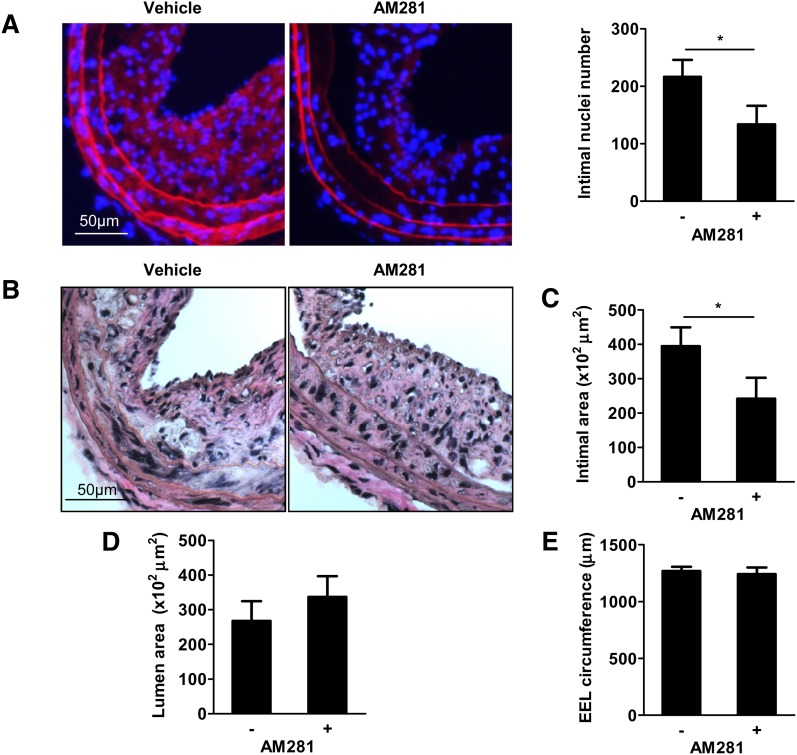

CB1 antagonism inhibits accelerated neointima formation in apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice

To determine whether the detrimental effects on neointima formation in apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice were dependent on CB1 activation, we treated mice with the selective CB1 antagonist AM281. Indeed, mice treated with AM281 had significantly reduced numbers of intimal nuclei and intimal areas in comparison to vehicle controls (Fig. 3AndashC, P < 0.05). Lumen area and EEL circumference were comparable between the two groups (Fig. 3B, D, E). AM281 administration did not affect body weight, cholesterol, and total blood leukocyte count (Tables 2, 3).

Fig. 3.

CB1 antagonism inhibits accelerated neointima formation in FAAH-deficient mice. A: Evans Blue/DAPI staining and intimal nuclei quantification in apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice treated with vehicle (n = 7) or AM281 (n = 5) 28 days postballooning. B–E: Van Gieson staining and morphometric analysis (n = 5–7). *P < 0.05.

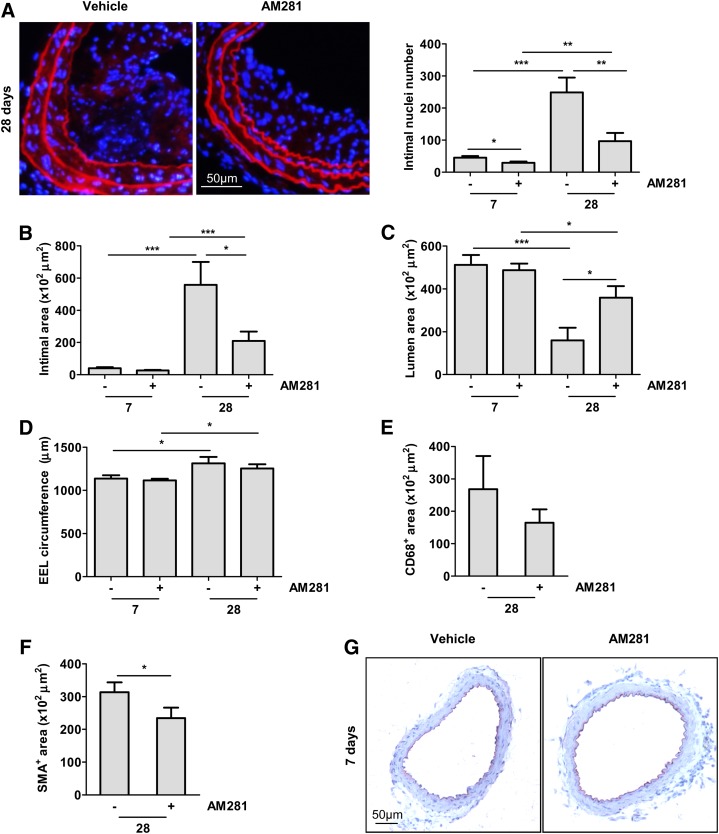

Therapeutic benefit of CB1 antagonism on neointima formation in apoE−/− mice

To confirm a potential therapeutic benefit of CB1 antagonism on neointima formation, we administered AM281 in apoE−/− mice subjected to balloon injury. Again, the treatment did not affect body weight, cholesterol profiles, and total blood leukocyte count (Tables 2, 3). After 7 to 28 days, intimal nuclei numbers and intimal areas were significantly lower in AM281-treated mice compared with the vehicle group (Fig. 4A, B). In both groups, the lumen area significantly decreased from 7 to 28 days due to neointimal thickening (Fig. 4C). However, the reduction of lumen area was lower in mice treated with the CB1 antagonist (Fig. 4C, P < 0.05). In both groups, the EEL circumference slightly increased from 7 to 28 days postinjury due to outward remodeling. (Fig. 4D, P < 0.05). We further determined which cell type was affected by the protective effects of CB1 antagonism. We found a nonsignificant tendency for decreased CD68-positive macrophage content (Fig. 4E), whereas SMC content determined by α-SMA staining was significantly reduced in AM281-treated mice (Fig. 4F, P < 0.05). To verify that CB1 antagonism with AM281 did not affect endothelial repair, we performed immunostaining of the endothelial cell marker platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (CD31). In both vehicle and AM281-treated mice, complete reendothelialization was observed after 7 days (Fig. 4G).

Fig. 4.

CB1 antagonism inhibits neointima formation in apoE−/− mice. A: Evans Blue/DAPI staining of carotid cross-sections and intimal nuclei quantification in apoE−/− mice treated with vehicle or AM281 7 (n = 9) and 28 days (n = 7) postballooning. B–D: Morphometric analysis. E–F: Quantification of CD68- (E) and α-SMA-positive (F) areas 28 days postballooning. G: CD31 immunostaining of apoE−/− mice treated with AM281 or vehicle 7 days postballooning. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.005 for two-group comparison.

CB1 deficiency or antagonism inhibits BMDM adhesion and migration as well as SMC proliferation

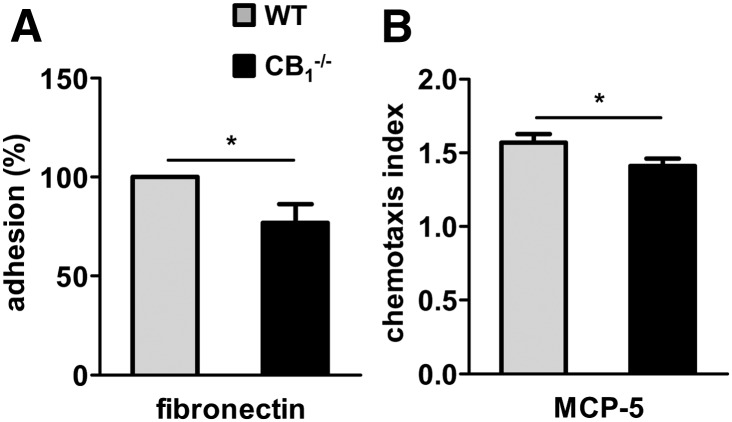

To strengthen our in vivo findings suggesting that SMCs rather than macrophages are the major cell type affected by CB1 antagonism, we performed a set of in vitro experiments. We therefore isolated macrophages from the bone marrow and SMCs from aortas of CB1−/− and WT mice. In addition, we isolated cells of apoE−/− and apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice. We found a moderate but significant reduction of adhesion to fibronectin and migration versus MCP-5 in CB1-deficient macrophages compared with WT (P < 0.05; Fig. 5A, B).

Fig. 5.

CB1 deficiency reduces macrophage adhesion and migration. A: Adhesion of wild-type (WT, gray bars) or CB1−/− (black bars) BMDM to fibronectin-coated culture dishes. B: Migration in response to 50 ng/ml MCP-5. n = 4, *P < 0.05.

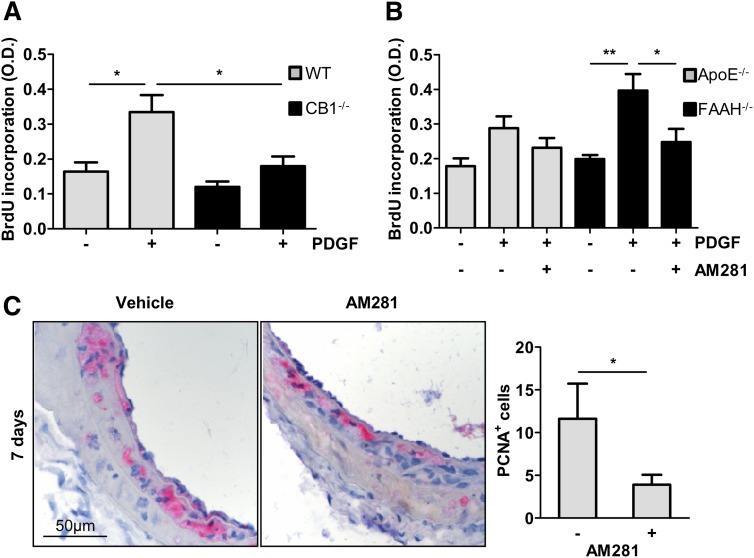

The SMC proliferation rate in response to PDGF was 1.86-fold lower in CB1−/− compared with WT cells (Fig. 6A, P < 0.05). We further investigated the effect of FAAH deficiency on SMC proliferation. The SMC proliferation in response to PDGF was higher in apoE−/−FAAH−/− compared with apoE−/− cells (Fig. 6B, P < 0.01), whereas AM281 significantly inhibited PDGF-induced proliferation of apoE−/− and apoE−/−FAAH−/− SMCs (P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

CB1 deficiency or antagonism inhibits SMC proliferation. In vitro proliferation of murine aortic SMCs in response to 25 ng/ml PDGF isolated from WT (gray bars, n = 4) and CB1−/− mice (black bars, n = 4) (A); apoE−/− (gray bars, n = 5) and apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice (black bars, n = 5) ± AM281 (10 μM) (B). C: Representative cross-sections and quantification of PCNA-positive cells in apoE−/− mice treated with AM281 or vehicle 7 days postballooning. O.D., optical density. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

To verify the relevance of these in vitro observations in vivo, we determined the number of proliferating cells in dilated arteries. Indeed, immunostaining of cross-sections revealed reduced numbers of PCNA-positive cells in AM281-treated mice 7 days post balloon injury (Fig. 6C, P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we investigated a potential activation and causal role of endocannabinoid signaling in neointima formation, a pathophysiological response to arterial injury. We provide evidence that enhanced lipid signaling through CB1 cannabinoid receptors contributes to the detrimental vascular responses induced by arterial injury. Increased systemic anandamide levels were accompanied by enhanced vascular CB1 expression at the site of injury. Hypercholesterolemic apoE−/− mice with elevated anandamide levels due to FAAH deficiency, the major enzyme involved in its metabolism, showed enhanced neointima formation. This effect was sensitive to CB1 antagonism, suggesting that it was attributable to the endocannabinoid anandamide. In fact, anandamide is a partial agonist at CB1 and CB2 receptors (CB1 Ki value = 61 to 543 nM, CB2 Ki value = 279 to 1,940 nM), with higher efficacy at CB1 than CB2 receptors. Other FAAH substrates that are also systemically elevated in FAAH-deficient mice, i.e., PEA and OEA (19), do not bind to CB1 and CB2 receptors, but are thought to activate PPAR-α (13, 14). The increase of anandamide in response to arterial injury was paralleled by reduced levels of the other major endocannabinoid, 2-AG, which is mainly metabolized by FAAH-independent pathways. A possible explanation might be enhanced expression and/or activity of its main metabolizing enzyme, monoacylglycerol lipase. Interestingly, the reduction of 2-AG levels was found in both apoE−/− and apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice, suggesting that regulation of 2-AG metabolism is independent of anandamide levels.

The lower serum LDL and HDL cholesterol levels observed in apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice could be related to changes in cholesterol accumulation and/or efflux. In fact, changes in lipid profiles have been reported in experimental and clinical studies using CB1 receptor antagonists (23). However, in the case of FAAH deficiency the effects on cholesterol seem to be independent of CB1, inasmuch as treatment with AM281 did not change lipid profiles in apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice.

The finding that FAAH deficiency resulted in accelerated neointima formation, which was, at least in part, attributable to CB1 activation, prompted us to further investigate the therapeutic potential of pharmacological CB1 antagonism. We confirmed the potent protective effect of the CB1 antagonist AM281 against neointima formation in hypercholesterolemic apoE−/− mice. Surprisingly, AM281 treatment did not affect macrophage content in neointimal areas. In vitro, we found a moderate but significantly reduced macrophage adhesion to fibronectin, as well as MCP-5-induced migration in CB1-deficient macrophages. Previous studies have suggested anti-inflammatory effects of CB1 antagonism in macrophages, including reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and thioglycollate-induced peritoneal macrophage recruitment (24, 25). Nevertheless, the immunohistological data do not support a major contribution of macrophages in CB1-mediated effects on neointima formation, at least in our model.

Our latest published findings demonstrate that FAAH deficiency leads to a striking increase of neutrophil recruitment into atherosclerotic plaques (19). This was related to enhanced expression of pro-inflammatory Th1 cytokines (TNF-α, IFN-γ) and increased local expression of neutrophil chemoattractant CXCL1 in mice lacking FAAH. However, in this model of neointima formation, neutrophils were barely detectable in neointimal lesions of apoE−/− and apoE−/−FAAH−/− mice as assessed after 1, 7, and 28 days after injury (data not shown). We may speculate that neutrophils are rarely recruited to neointimal lesions, although their presence in neointimal lesions and their pathophysiological role has been previously evidenced (26, 27). In particular, neutrophil-derived granule proteins were shown to play a protective role by promoting reendothelialization (27).

As opposed to potential effects on immune cells, our data suggest that the protective effect of CB1 antagonism on neointima formation is largely attributable to inhibition of SMC proliferation. This is in agreement with previous in vitro data reporting decreased proliferation and migration of PDGF-stimulated human coronary artery SMCs in response to the CB1 antagonist rimonabant (16). In this study, rimonabant was found to attenuate intracellular Ras and ERK1/2 signaling pathways.

To exclude the possibility of nonspecific effects in response to pharmacological CB1 blockade, we confirmed the role of CB1 in SMC proliferation by using CB1−/− SMCs. Remarkably, we observed a functional effect in isolated CB1−/− and FAAH−/− macrophages and SMCs compared with WT cells without addition of exogenous ligands. This clearly indicates the release of endogenous CB1 receptor ligands upon stimulation which act in an autocrine manner to activate CB1. This could involve the FAAH substrate anandamide, but also structurally related lipid mediators PEA and OEA. However, as mentioned above, these other N-acylethanolamines do not activate CB1 and CB2 receptors, but activate PPAR-α. A putative effect of these lipid mediators on vascular SMCs is unclear and deserves further investigation in subsequent studies. Another unresolved question remains the pathophysiological role of downregulated 2-AG levels in our model.

Finally, it is particularly noteworthy that the CB1 antagonist AM281 did not negatively affect endothelial repair in this model. This is of crucial importance, inasmuch as delayed endothelialization is largely responsible for thrombotic complications following catheter-based interventions. Today, the frequently used drug-eluting stents reduce rates of restenosis compared with bare metal stents. However, late thrombosis, a life threatening complication, has emerged as a major safety concern (28–30). In fact, a key player in the pathogenesis of late stent thrombosis is delayed healing, characterized by persistent fibrin deposition and the lack of complete endothelial repair (31). Thus, the development of novel strategies to prevent restenosis without impairing the arterial healing process is of crucial importance.

In conclusion, endocannabinoid signaling through CB1 receptors plays a detrimental role in neointima formation by stimulating SMC proliferation, suggesting a potential therapeutic benefit of CB1 receptor blockade.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Sebastien Lenglet for his support in genotyping of mouse strains.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- 2-AG

- 2-arachidonoylglycerol

- BMDM

- bone marrow-derived macrophages

- EEL

- external elastic lamina

- FAAH

- FA amide hydrolase

- OEA

- oleoylethanolamide

- PCNA

- proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- PDGF

- platelet-derived growth factor

- PEA

- palmitoylethanolamide

- PFA

- paraformaldehyde

- PPAR-α

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α

- α-SMA

- α-smooth-muscle actin

- SMC

- smooth-muscle cell

- WT

- wild type

This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant #310030_130732/1), Prevot, OPO Foundation, and Swiss Life (S.S.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bittl J. A. 1996. Advances in coronary angioplasty. N. Engl. J. Med. 335: 1290–1302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bittl J. A., Hirsch A. T. 2004. Concomitant peripheral arterial disease and coronary artery disease: therapeutic opportunities. Circulation. 109: 3136–3144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferns G. A., Avades T. Y. 2000. The mechanisms of coronary restenosis: insights from experimental models. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 81: 63–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schober A. 2008. Chemokines in vascular dysfunction and remodeling. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28: 1950–1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwartz S. M. 1997. Perspectives series: cell adhesion in vascular biology. Smooth muscle migration in atherosclerosis and restenosis. J. Clin. Invest. 99: 2814–2816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hao H., Gabbiani G., Bochaton-Piallat M. L. 2003. Arterial smooth muscle cell heterogeneity: implications for atherosclerosis and restenosis development. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 23: 1510–1520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Windecker S., Meier B. 2007. Late coronary stent thrombosis. Circulation. 116: 1952–1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raber L., Wohlwend L., Wigger M., Togni M., Wandel S., Wenaweser P., Cook S., Moschovitis A., Vogel R., Kalesan B., Seiler C., et al. 2011. Five-year clinical and angiographic outcomes of a randomized comparison of sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents: results of the Sirolimus-Eluting Versus Paclitaxel-Eluting Stents for Coronary Revascularization LATE trial. Circulation. 123: 2819–2828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stähli B. E., Camici G. G., Steffel J., Akhmedov A., Shojaati K., Graber M., Luscher T. F., Tanner F. C. 2006. Paclitaxel enhances thrombin-induced endothelial tissue factor expression via c-Jun terminal NH2 kinase activation. Circ. Res. 99: 149–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pacher P., Steffens S. 2009. The emerging role of the endocannabinoid system in cardiovascular disease. Semin. Immunopathol. 31: 63–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cravatt B. F., Demarest K., Patricelli M. P., Bracey M. H., Giang D. K., Martin B. R., Lichtman A. H. 2001. Supersensitivity to anandamide and enhanced endogenous cannabinoid signaling in mice lacking fatty acid amide hydrolase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98: 9371–9376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pertwee R. G. 2005. Pharmacological actions of cannabinoids. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 168: 1–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guzmán M., Lo Verme J., Fu J., Oveisi F., Blazquez C., Piomelli D. 2004. Oleoylethanolamide stimulates lipolysis by activating the nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR-alpha). J. Biol. Chem. 279: 27849–27854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo Verme J., Fu J., Astarita G., La Rana G., Russo R., Calignano A., Piomelli D. 2005. The nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha mediates the anti-inflammatory actions of palmitoylethanolamide. Mol. Pharmacol. 67: 15–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajesh M., Mukhopadhyay P., Hasko G., Huffman J. W., Mackie K., Pacher P. 2008. CB(2) cannabinoid receptor agonists attenuate TNF-alpha-induced human vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration. Br. J. Pharmacol. 153: 347–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajesh M., Mukhopadhyay P., Hasko G., Pacher P. 2008. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor inhibition decreases vascular smooth muscle migration and proliferation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 377: 1248–1252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molica F., Matter C. M., Burger F., Pelli G., Lenglet S., Zimmer A., Pacher P., Steffens S. 2012. Cannabinoid receptor CB2 protects against balloon-induced neointima formation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 302: H1064–H1074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Long J. Z., LaCava M., Jin X., Cravatt B. F. 2011. An anatomical and temporal portrait of physiological substrates for fatty acid amide hydrolase. J. Lipid Res. 52: 337–344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lenglet S., Thomas A., Soehnlein O., Montecucco F., Burger F., Pelli G., Galan K., Cravatt B. F., Staub C., Steffens S. 2013. Fatty acid amide hydrolase deficiency enhances intraplaque neutrophil recruitment in atherosclerotic mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33: 215–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matter C. M., Ma L., von Lukowicz T., Meier P., Lohmann C., Zhang D., Kilic U., Hofmann E., Ha S. W., Hersberger M., et al. 2006. Increased balloon-induced inflammation, proliferation, and neointima formation in apolipoprotein E (ApoE) knockout mice. Stroke. 37: 2625–2632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas A., Hopfgartner G., Giroud C., Staub C. 2009. Quantitative and qualitative profiling of endocannabinoids in human plasma using a triple quadrupole linear ion trap mass spectrometer with liquid chromatography. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 23: 629–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zimmer A., Zimmer A. M., Hohmann A. G., Herkenham M., Bonner T. I. 1999. Increased mortality, hypoactivity, and hypoalgesia in cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96: 5780–5785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pacher P. 2009. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists for atherosclerosis and cardiometabolic disorders: new hopes, old concerns? Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29: 7–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dol-Gleizes F., Paumelle R., Visentin V., Mares A. M., Desitter P., Hennuyer N., Gilde A., Staels B., Schaeffer P., Bono F. 2009. Rimonabant, a selective cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist, inhibits atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29: 12–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sugamura K., Sugiyama S., Nozaki T., Matsuzawa Y., Izumiya Y., Miyata K., Nakayama M., Kaikita K., Obata T., Takeya M., et al. 2009. Activated endocannabinoid system in coronary artery disease and antiinflammatory effects of cannabinoid 1 receptor blockade on macrophages. Circulation. 119: 28–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shagdarsuren E., Bidzhekov K., Mause S. F., Simsekyilmaz S., Polakowski T., Hawlisch H., Gessner J. E., Zernecke A., Weber C. 2010. C5a receptor targeting in neointima formation after arterial injury in atherosclerosis-prone mice. Circulation. 122: 1026–1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soehnlein O., Wantha S., Simsekyilmaz S., Doring Y., Megens R. T., Mause S. F., Drechsler M., Smeets R., Weinandy S., Schreiber F., et al. 2011. Neutrophil-derived cathelicidin protects from neointimal hyperplasia. Sci. Transl. Med. 3: 103ra198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finn A. V., Nakazawa G., Joner M., Kolodgie F. D., Mont E. K., Gold H. K., Virmani R. 2007. Vascular responses to drug eluting stents: importance of delayed healing. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27: 1500–1510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joner M., Finn A. V., Farb A., Mont E. K., Kolodgie F. D., Ladich E., Kutys R., Skorija K., Gold H. K., Virmani R. 2006. Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans: delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48: 193–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lüscher T. F., Steffel J., Eberli F. R., Joner M., Nakazawa G., Tanner F. C., Virmani R. 2007. Drug-eluting stent and coronary thrombosis: biological mechanisms and clinical implications. Circulation. 115: 1051–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joner M., Nakazawa G., Finn A. V., Quee S. C., Coleman L., Acampado E., Wilson P. S., Skorija K., Cheng Q., Xu X., et al. 2008. Endothelial cell recovery between comparator polymer-based drug-eluting stents. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 52: 333–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]