Abstract

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally and the American cancer society estimates approximately 226,160 new cases and 160,340 deaths from lung cancer in the USA in the year 2012. The majority of lung cancers are diagnosed in the later stages which impacts the overall survival. The 5-year survival rate for pathological st age IA lung cancer is 73% but drops to only 13% for stage IV. Thus, early detection through screening and prevention are the keys to reduce the global burden of lung cancer. This article discusses the current state of lung cancer screening, including the results of the National Lung Cancer Screening Trial, the consideration of implementing computed tomography screening, and a brief overview of the role of bronchoscopy in early detection and potential biomarkers that may aid in the early diagnosis of lung cancer.

Keywords: Early detection, lung cancer, screening

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally and the American cancer society estimates approximately 226,160 new cases and 160,340 deaths from lung cancer in the USA in the year 2012.[1] Almost 90% of lung cancers are attributed to smoking and unfortunately even the latest trend shows that 19.3% (45.3 million) of US adults continue to be active smokers.[2] Former smokers continue to be at elevated risk for lung cancer, constituting 50% of all newly diagnosed lung cancer cases. Estimates suggest that approximately 90 million people in the USA are at risk of a smoking-related lung cancer. This will continue to remain a substantial public health problem for years to come.

Compounding the sheer numbers of lung cancer, despite advances in the treatment strategies, the overall 5-year survival of lung cancer remains dismal at 16%.[1] One of the reasons for this poor survival is that only 15% of cases are diagnosed in the early localized stages[1] where there is the highest chance of survival. The 5-year survival rate for pathological stage IA lung cancer is 73% but drops to only 13% for stage IV.[3] Thus, early detection and prevention are the keys to succeeding in the global fight against lung cancer.

This article discusses the current state of lung cancer screening, including the results of the National lung cancer screening trial (NLST), the consideration of implementing CT screening, and a brief overview of the role of bronchoscopy in early detection and potential biomarkers that may aid in the early diagnosis of lung cancer.

OVERVIEW OF CONCEPTS FOR CANCER SCREENING

The aim of screening for a disease is to detect disease in the early asymptomatic stage when treatment has high chance of success. An effective screening test should be highly sensitive and specific with low false-positive rate and it should be cost-effective, safe, accessible, reproducible, and above all, it should reduce the disease-specific mortality.[4] The disease should have a preclinical phase that is long enough that it can be detected by screening and effective treatment for screen-detected disease should be available. However, there are some important concepts that must be considered before embarking on screening. The standard against which the effectiveness of a screening test is judged changes in the disease-specific mortality or the number of deaths from the disease with number of individual screened as denominator.[4] A lack of improvement in mortality from the disease may result from simply an earlier diagnosis of the disease without a change in the outcome (lead time bias), the extension of the time from diagnosis to death without a change in the mortality rate (length time bias), or the diagnosis of disease that is not likely to become deadly (overdiagnosis bias). No matter how effective a screening test is, there will always be interval cancers. Because we really do not know the natural history of early lung cancers, we cannot estimate the rates of interval lung cancers across multiple risk groups until there is more experience with detecting this disease early and screening over long periods of time.

Lung cancer screening with chest radiograph

Lung cancer has a long preclinical phase and generally starts as a nodule with a volume doubling time of typically 160-180 days[5] that raised the possibility of detecting it in early stages by imaging. Several large trials of lung cancer screening with chest radiographs and some with sputum evaluation were conducted in 1970s when central squamous cell histology was leading type of lung cancer (vs. the current trends in the USA where adenocarcinoma is the predominant histology) including three large National Cancer Institute sponsored trials in the USA (Mayo Clinic, John Hopkins, and Memorial-Sloan Kettering) and one in Czechoslovakia.[6–8] Unfortunately these trials, along with the results of recently reported prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian cancer screening (PLCO) trial, did not show any reduction of disease-specific mortality, although a higher fraction of resectable early stage disease was found.[7,9] These data are likely due in part to high false-positive rates and sub-optimal detection of small lung nodules by chest radiographs. In addition, the results suggest that lead time, length time, and overdiagnosis bias also had substantial influence.[10] In conclusion, the chest radiograph as a tool for lung cancer screening is no longer recommended.

Lung cancer screening with chest computed tomography

The low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) of the chest without contrast was considered a promising screening tool for lung cancer because it could detect small lung nodules using multi-detector technology with thin cuts and a lower dose of radiation. Several clinical screening trials were initiated in 1990s to evaluate the utility of this test.[11] Evidence from a prospective single-arm cohort trial suggested that LDCT resulted in the detection of earlier stage lung cancers with an improved survival rate.[12] However, questions remained about the influence of overdiagnosis on the results.[4] A meta-analysis of six randomized clinical trials of lung cancer screening with LDCT was published in 2010 and indicated that although a higher proportion of early stage lung cancers were detected, the rate of false-positive benign lesions was very high.[13] For every 1,000 individuals screened with LDCT, nine cases of stage 1 non-small-cell cancer were identified. At the same time, 235 benign nodules were identified that resulted in four unnecessary thoracotomies.[13] In addition, concerns of overdiagnosis and other biases persisted.[14,15] Above all, none of these studies showed a lung cancer-specific mortality benefit because they were not adequately powered and had an insufficient duration of follow-up. The NLST, the largest trial of lung cancer screening ever designed, was powered to answer several of these key questions and it now serves as the basis of several guidelines and future public policy decisions for lung cancer screening.

THE NATIONAL LUNG CANCER SCREENING TRIAL

The NLST was a NCI sponsored large multi-institutional trial (33 centers in the USA) comparing annual LDCT with annual chest radiographs for 3 years.[8,16,17] The trial recruited patients from August 2002 until April 2004 and subjects were followed-up until December 2009 (median: Follow-up 6.5 years). A total of 53,454 patients in the ages between 55 and 74 with a smoking history of at least 30 pack years were enrolled. Former smokers must have quit within the preceding 15 years to be enrolled. Exclusion criteria included history of lung cancer and the use of home oxygen support. The approximate radiation dose for each chest radiograph and LDCT was 0.02 mSv and 1.5 mSv, respectively (as compared to conventional chest CT dose of 8 mSv).[8] Adherence to the protocol was >90% in both groups. The findings of a nodule >4 mm, adenopathy, or effusions were considered to be suspicious and deemed to be a positive finding. Overall, 24.2% of LDCT and 6.9% of chest radiographs were positive over three screens and 96.4% and 94% of these nodules were deemed false positive, respectively. Further diagnostic work-up involved mainly imaging modalities while invasive tests were infrequent (invasive procedure performed on only 11.4% in LDCT group including 4% undergoing surgery). The rate of at least one complication from diagnostic tests was low at 1.4% in LDCT group and 1.6% in chest radiograph group.

A total of 1,060 lung cancers were diagnosed in LDCT arm and 941 in chest radiograph arm (645 and 572 per 100,000 person-years, respectively). Of the 1060 cancers in LDCT group, 649 (61%) were detected by screening, 44 (4%) were interval cancers, and 367 (35%) were found in participants who missed the screening or were still in follow-up after the 3rd year of screening was done. In the LDCT arm, 356 patients died of lung cancer, whereas 443 participants died of lung cancer in the chest radiograph arm. These numbers correspond to 247 and 309 deaths per 100,000 person-years, respectively. The LDCT group had a 20% relative reduction in lung cancer-specific mortality (95% CI, 6.8-26.7; P = 0.004) and 6.7% reduction in all-cause mortality (95% CI, 1.2-13.6; P = 0.02). This was the first randomized trial of lung cancer screening using LDCT that showed a significant decrease in lung cancer-specific mortality. These data show that in this population, 320 subjects needed to be screened with annual LDCT for 3 years to prevent one lung cancer death. The mortality benefit may be even higher in real practice as chest radiographs are not customarily done for lung cancer screening and the new generations of LDCT scanners are superior (though this may also transcribe into even higher false-positive rate). Due to logistic and economic issues, this study was not able to determine survival benefits of LDCT screening over a longer duration. In the LDCT arm, 40% of the lung cancers were detected in stage IA and 21.7% in stage IV compared to 21% of cancers being stage IA and 36% being stage IV in chest radiograph arm. This suggests that as LDCT is used more widely for lung cancer screening, there may be persistent changes in the rates of early lung cancers diagnosed, offering more patients surgical options for treatment.

ONGOING TRIALS OF LOW-DOSE COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY SCREENING

Several European trials of lung cancer screening with LDCT are ongoing including DANTE trial in Italy,[18] Danish randomized lung cancer CT screening trial,[19] and the Dutch Belgian randomized lung cancer screening trial (http://www.trialregister.nl/trialreg/admin/rctview.asp?TC = 636) (Dutch acronym: NELSON) that has routine care and not a chest radiograph in control arm.[20–22] This trial is the only trial that may have a sufficient sample size to possibly detect a mortality difference, as other trials are small. The trial is different as it also enrolls 5-year lung cancer survivors who are at very high risk of lung cancer, has a detailed assessment of smoking cessation in context of screening program, and looks into cost-effectiveness, quality of life as well as volumetric assessment of nodules to reduce false positives.[22] This trial is expected to complete in 2015.

CURRENT RECOMMENDATIONS REGARDING LUNG CANCER SCREENING WITH LOW-DOSE COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

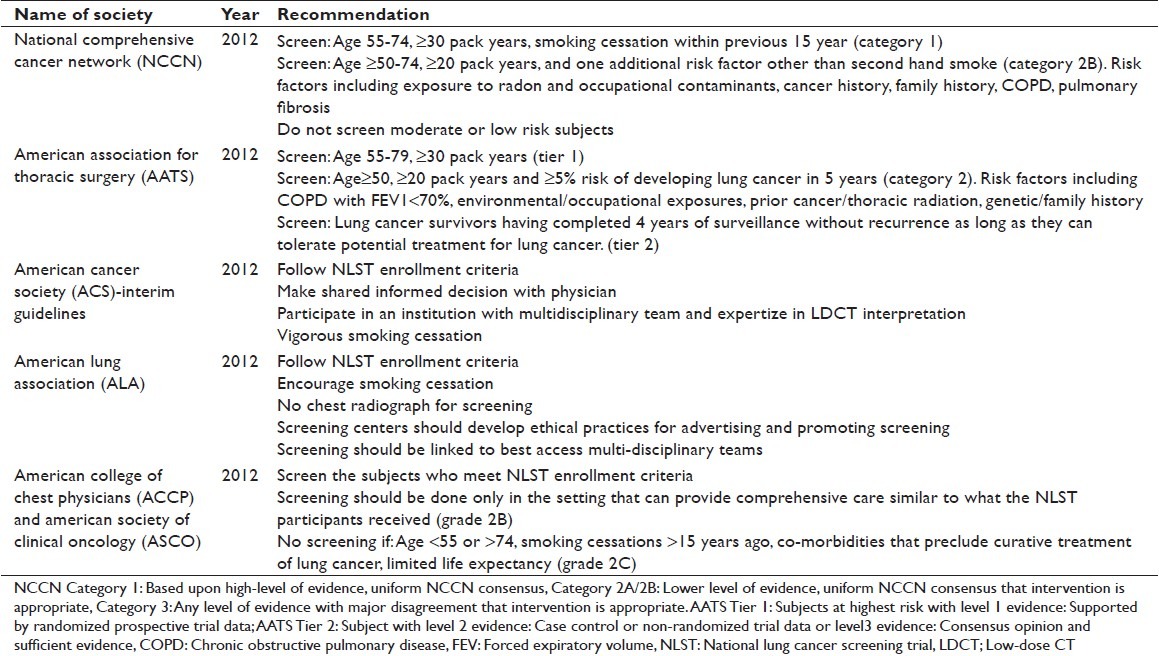

In the wake of NLST results, several professional organizations have developed guidelines for lung cancer screening.[4,23–26] Most agree that screening should include patients who meet the NLST inclusion criteria. The national comprehensive cancer network (NCCN) and american thoracic society (ATS) additionally recommend LDCT screening for patients who are 50 years or older with 20 pack years or more smoking history and who have an additional lung cancer risk factor, like environmental exposure or family history.[26] The American Association of Thoracic Surgery recommends increasing the upper age limit of screening to 79 because the peak incidence of lung cancer is at 70 years in the USA and with the average life expectancy is 79 years, at least half of Americans are expected to live until the age of 80-89 years.[25] Aggressive smoking cessation and performing screening in a center with a multi-disciplinary team, similar to NLST institutions, are also recommended by most organizations. A brief summary of these guidelines is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Recommendations of various organizations for lung cancer screening

SCREENING FOR LUNG CANCER WITH BRONCHOSCOPY

Several published studies have utilized bronchoscopy, coupled with LDCT, for the detection of early central premalignant lesions that are typically precursors for squamous cell carcinoma.[27–32] Although none of the national professional organizations have recommended the use of bronchoscopy for lung cancer screening, there are several programs, both research and clinical, based at large tertiary care centers that utilize bronchoscopy in patients at high risk for lung cancer. The majority of these programs also use devices that combine white light and autofluorescence imaging during the procedure, which has been shown to increase the detection of dysplasia.[33,34]

Access to the airway through bronchoscopy, while not likely to be applied as a standard screening exam in the immediate future, provides important sampling opportunities of the central lung field that can impact our understanding of biomarkers of lung field damage and early carcinogenesis. Although the majority of lung cancers now develop as adenocarcinoma in the distal segments of the lung that are not accessible by bronchoscopy, identifying biomarkers of field damage that may help to improve defining lung cancer risk, risk of recurrence, or risk of nodules that harbor cancer is an important step to conquering lung cancer.

THE STATE OF THE ART OF BIOMARKERS FOR LUNG CANCER DETECTION

With the advent of lung cancer screening recommendations for high-risk subjects, the need for biomarkers to aid in the identification of lung cancer risk and early stage disease becomes even more important.[35] Ideally, validated biomarkers of early lung cancer would serve to supplement LDCT findings and identify the indiscriminant lung nodules that carry the highest probability of harboring cancer. Validated markers could guide the use of interventional diagnostic testing and better classify the state of the lung field in characterizing lung cancer risk. There are many biomarkers currently under development that use several state-of-the-art technologies and utilize several different biospecimens. The key to this strategy is to identify either changes in the lung field or early lesions that will signal potential risk of lung cancer in the detected nodule or in the future.

There have been several recent reviews of the ongoing potential biomarkers for lung cancer.[36–39] A recent comprehensive review by Hassanein et al.,[40] documents the published candidate biomarkers and the spectrum of biospecimens that are being used. The tissue types include bronchial biopsies and brushes of normal and abnormal areas, tumor and adjacent normal tissue from surgical resections, serum, plasma and whole blood, sputum, and exhaled breath concentrate. The most promising markers under investigation range from specific mutations in the DNA from tumors, DNA methylation, mRNA expression arrays, miRNA signatures, proteins and proteomic signatures, autoantibodies, volatile organic compounds, and circulating tumor cells. The breadth of both the tissue types and the marker technologies demonstrates the need for methods to identify the populations at highest risk of lung cancer, to develop earlier interventions and more effective, targeted treatments.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR IMPLEMENTING LOW-DOSE COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY SCREENING

Although the NLST has ushered a new era in lung cancer screening, a few questions remain unanswered and several concerns have been raised about generalizing these results into the routine general practice:

The NLST participants were comparatively younger, better educated, and less likely to be current smokers as compared to general population based on US Census Survey,[16] a phenomenon also described as the “healthy volunteer” effect and also noted in the large PLCO trial. The average age at diagnosis of lung cancer in the USA is 70 and only 8.8% of participants of NLST were in age group of 70-74 years.

The smokers as a high-risk group may be difficult to target in the community because as a group they have higher chance of being poor, less well educated, have less access to screening and preventive services, such as smoking cessation. They are also more likely to less likely to participate in screening or pay for it.[41,42]

The compliance rate with screening in NLST was very high at >90% which may be difficult to replicate in standard practice settings.

The NLST was conducted in high volume urban tertiary care hospitals and the morality rate associated with surgical resections was very low at 1% as compared 3-6% rate reported in US general population.[43] It has been shown that survival after lung cancer resection is directly related to volume of surgeries performed at the institution and the use of thoracic surgeons over general surgeons.[43,44] The practice patterns of invasive diagnostic procedures may also vary and a recent report demonstrated an almost two-fold variation among geographical regions in the utilization of CT-guided biopsy.[45] Therefore, the extremely low rate of complications and low mortality may not be replicable in all settings.

The NLST utilized rigorous quality control to standardize the radiology equipment and LDCT interpretation. Only NLST approved expert radiologists, utilizing standardized protocols, reviewed the scans. Even with the precautions, variations in LDCT interpretation existed even between radiologists in high volume NLST study centers. These issues will only be compounded when screening is implemented in multiple centers and community practices.[46]

The NLST did not offer insight into the optimal duration of screening. A longer follow-up period would have clarified whether long-term screening had additional survival benefits and the potential role of overdiagnosis bias. The LDCT arm saw 120 more lung cancers than chest radiograph arm, suggesting that some overdiagnosis may have occurred.

The rate of false-positive findings seen in NLST is very high and the cost of the work-up can be prohibitive. In addition, as per the NLST protocol, the work-up and management of positive findings were determined by the individual healthcare providers. Thus, at the end of the trial, it is difficult to formulate standardized guidelines for management of abnormal findings on LDCT. The lung nodule guidelines by Fleishner society and recent guidelines on ground glass opacities are steps in right direction.[5,47] Volumetric growth rate assessment of CT lesions was incorporated into the NELSON trial which may also help to reduce false positives.[22] Again, this approach is costly, personnel intensive, and requires a certain level of expertise and must be evaluated before it is recommended for the broader community.

The issue of cost-effectiveness of screening needs to be analyzed further. Based on current NLST enrolling criteria, around 7 million people in the USA will qualify and there are around 94 million current and former smokers at risk of lung cancer.[8] Concern has been raised that the absolute number of deaths prevented by LDCT was low. The cost-effectiveness needs to take into account the rising cost of management of lung cancer in the era of aggressive surveillance and targeted therapy. Cost-effectiveness can improve and the number of patients (320) needed to be screened to find one lung cancer can decrease if the population screened has a greater risk than the participants enrolled in NLST.

The NLST recruited patients who had only smoking as a risk factor. The role of screening in patients with additional risk factors such as radon exposure, pulmonary fibrosis, asbestosis, and genetic factors/family history needs to be answered. Degree of lung function impairment and co-morbidities were not evaluated Developing risk prediction models that take into account the other risk factors may be helpful to decide about eligibility for screening.

The risk of radiation exposure from LDCT and any further radiological tests to evaluate positive findings have not been directly studied and data extrapolated from atomic bomb survivors are generally used. Brenner estimated that a 50-year-old smoker who undergoes annual LDCT until age 75 is at 0.85% risk of lung cancer from smoking in addition to 17% risk already incurred from smoking.[48] The Radiological Society of North America and The American College of radiology (http://www.radiologyinfo.org) classify the additional lifetime risk of cancer from a LDCT as very low (1 per 10,000 to 1 per 100,000 persons). However, the cumulative radiation exposure from multiple tests can be a cause for concern and needs to be evaluated and the current goal for radiation exposure should remain “As low as possible.”

Prevention is better than cure.” Since smoking cessation is a much less expensive and safer alternative to lung cancer screening, it should be the first public policy goal. Coordinating a smoking cessation intervention at the time of screening may be an optimal time to motivate more people to quit. However, there is concern that negative LDCT test results may provide smokers with a rationale to continue to smoke. Educating patients on the risk of lung cancer and other smoking-related diseases will be an important component to these efforts. The ongoing randomized NELSON trial is looking at these issues and early results suggest that screening may be a valuable teachable moment for smoking cessation.[49]

In summary, at this time, it is appropriate to offer lung cancer screening with LDCT to high-risk individuals after a discussion of the pros and cons of screening. It also seems critical that screening programs be highly integrated with smoking cessation programs. Screening programs should only be administered by well-equipped centers with multi-disciplinary teams that can evaluate and treat all abnormal findings and provide consistent ongoing follow-up, similar to those involved in the NLST centers. As the utility of bronchoscopy as a secondary screening tool is defined in high-risk populations, it may also be added to the screening program. In the future, the incorporation of validated biomarkers into lung cancer screening will improve the assessment of lung cancer risk, direct interventional diagnostic procedures, and may provide identifiable targets for chemoprevention and treatment.

AUTHOR'S PROFILE

Dr. Samjot Singh Dhillon, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, New York, USA

Dr. Gregory Loewen, Providence Regional Cancer Center, Spokane, WA, USA

Dr. Vijayvel Jayaprakash, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, New York, USA

Dr. Mary E. Reid, Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, New York, USA

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Vital signs: Current cigarette smoking among adults aged ≥8 years – United States, 2005-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1207–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, Giroux DJ, Groome PA, Rami-Porta R, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:706–14. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wood DE, et al. Lung cancer screening. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:240–65. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacMahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, Herold CJ, Jett JR, Naidich DP, et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: A statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology. 2005;237:395–400. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2372041887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holin SM, Dwork RE, Glaser S, Rikli AE, Stocklen JB. Solitary pulmonary nodules found in a community-wide chest roentgenographic survey; a five-year follow-up study. Am Rev Tuberc. 1959;79:427–39. doi: 10.1164/artpd.1959.79.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eddy DM. Screening for lung cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:232–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-3-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Black WC, Clapp JD, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oken MM, Hocking WG, Kvale PA, Andriole GL, Buys SS, Church TR, et al. Screening by chest radiograph and lung cancer mortality: The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;306:1865–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patz EF, Jr, Goodman PC, Bepler G. Screening for lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1627–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henschke CI, McCauley DI, Yankelevitz DF, Naidich DP, McGuinness G, Miettinen OS, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project: Overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet. 1999;354:99–105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)06093-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Libby DM, Pasmantier MW, Smith JP, et al. Survival of patients with stage I lung cancer detected on CT screening. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1763–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060476. International Early Lung Cancer Action Program Investigators. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gopal M, Abdullah SE, Grady JJ, Goodwin JS. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the baseline findings of randomized controlled trials. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1233–9. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181e0b977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reich JM. A critical appraisal of overdiagnosis: Estimates of its magnitude and implications for lung cancer screening. Thorax. 2008;63:377–83. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.079673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Welch HG, Black WC. Overdiagnosis in cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:605–13. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, Clapp JD, Clingan KL, et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the randomized national lung screening trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1771–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq434. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aberle DR, Berg CD, Black WC, Church TR, Fagerstrom RM, et al. The National Lung Screening Trial: Overview and study design. Radiology. 2011;258:243–53. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091808. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Infante M, Lutman FR, Cavuto S, Brambilla G, Chiesa G, Passera E, et al. Lung cancer screening with spiral CT: Baseline results of the randomized DANTE trial. Lung Cancer. 2008;59:355–63. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2007.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pedersen JH, Ashraf H, Dirksen A, Bach K, Hansen H, Toennesen P, et al. The Danish randomized lung cancer CT screening trial – Overall design and results of the prevalence round. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:608–14. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181a0d98f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Iersel CA, de Koning HJ, Draisma G, Mali WP, Scholten ET, Nackaerts K, et al. Risk-based selection from the general population in a screening trial: Selection criteria, recruitment and power for the Dutch-Belgian randomised lung cancer multi-slice CT screening trial (NELSON) Int J Cancer. 2007;120:868–74. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ru Zhao Y, Xie X, de Koning HJ, Mali WP, Vliegenthart R, Oudkerk M. NELSON lung cancer screening study. Cancer Imaging. 2011;11:S79–84. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2011.9020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Klaveren RJ, Oudkerk M, Prokop M, Scholten ET, Nackaerts K, Vernhout R, et al. Management of lung nodules detected by volume CT scanning. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2221–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fontham ET, Wender R. American Cancer Society Interim Guidance on Lung Cancer Screening, 2012. [Last accessed: January 29, 2013]. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/acspc-030879.pdf .

- 24.Bach PB, Mirkin JN, Oliver TK, Azzoli CG, Berry DA, Brawley OW, et al. Benefits and harms of CT screening for lung cancer: A systematic review. JAMA. 2012;307:2418–29. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaklitsch MT, Jacobson FL, Austin JH, Field JK, Jett JR, Keshavjee S, et al. The American Association for Thoracic Surgery guidelines for lung cancer screening using low-dose computed tomography scans for lung cancer survivors and other high-risk groups. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:33–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Providing Guidance on Lung Cancer Screening To Patients and Physicians, 2012. [Last accessed: January 29, 2013]. Available from: http://www.lung.org/lung-disease/lung-cancer/lung-cancer-screening-guidelines/lung-cancer-screening.pdf .

- 27.McWilliams A, Mayo J, MacDonald S, leRiche JC, Palcic B, Szabo E, et al. Lung cancer screening: A different paradigm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1167–73. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-144OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lam S, MacAulay C, Le Riche JC, Dyachkova Y, Coldman A, Guillaud M, et al. A randomized phase IIb trial of anethole dithiolethione in smokers with bronchial dysplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1001–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.13.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merrick DT, Kittelson J, Winterhalder R, Kotantoulas G, Ingeberg S, Keith RL, et al. Analysis of c-ErbB1/epidermal growth factor receptor and c-ErbB2/HER-2 expression in bronchial dysplasia: Evaluation of potential targets for chemoprevention of lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2281–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keith RL, Blatchford PJ, Kittelson J, Minna JD, Kelly K, Massion PP, et al. Oral iloprost improves endobronchial dysplasia in former smokers. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:793–802. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loewen G, Natarajan N, Tan D, Nava E, Klippenstein D, Mahoney M, et al. Autofluorescence bronchoscopy for lung cancer surveillance based on risk assessment. Thorax. 2007;62:335–40. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.068999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loewen GM, et al. Detection of premalignant bronchial epithelial abnormalities in high-risk patients. Proc ASCO. 2002;21:447. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lam S, Palcic B. Re: Autofluorescence bronchoscopy in the detection of squamous metaplasia and dysplasia in current and former smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:561–2. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.6.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edell E, Lam S, Pass H, Miller YE, Sutedja T, Kennedy T, et al. Detection and localization of intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive carcinoma using fluorescence-reflectance bronchoscopy: An international, multicenter clinical trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:49–54. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181914506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Massion PP, Carbone DP. The molecular basis of lung cancer: Molecular abnormalities and therapeutic implications. Respir Res. 2003;4:12. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gomperts BN, Spira A, Elashoff DE, Dubinett SM. Lung cancer biomarkers: FISHing in the sputum for risk assessment and early detection. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:420–3. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perdomo C, Spira A, Schembri F. MiRNAs as regulators of the response to inhaled environmental toxins and airway carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 2011;717:32–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Malerba M, Ragnoli B, Corradi M. Non-invasive methods to assess biomarkers of exposure and early stage of pulmonary disease in smoking subjects. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2008;69:128–33. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2008.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang YW, Chen LA. microRNAs as tumor inhibitors, oncogenes, biomarkers for drug efficacy and outcome predictors in lung cancer (review) Mol Med Report. 2012;5:890–4. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hassanein M, Callison JC, Callaway-Lane C, Aldrich MC, Grogan EL, Massion PP. The state of molecular biomarkers for the early detection of lung cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:992–1006. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Silvestri GA. Screening for lung cancer: It works, but does it really work? Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:537–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silvestri GA, Nietert PJ, Zoller J, Carter C, Bradford D. Attitudes towards screening for lung cancer among smokers and their non-smoking counterparts. Thorax. 2007;62:126–30. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.056036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bach PB, Cramer LD, Schrag D, Downey RJ, Gelfand SE, Begg CB. The influence of hospital volume on survival after resection for lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:181–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107193450306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Silvestri GA, Handy J, Lackland D, Corley E, Reed CE. Specialists achieve better outcomes than generalists for lung cancer surgery. Chest. 1998;114:675–80. doi: 10.1378/chest.114.3.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiener RS, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Welch HG. Population-based risk for complications after transthoracic needle lung biopsy of a pulmonary nodule: An analysis of discharge records. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:137–44. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gierada DS, Pilgram TK, Ford M, Fagerstrom RM, Church TR, Nath H, et al. Lung cancer: Inter observer agreement on interpretation of pulmonary findings at low-dose CT screening. Radiology. 2008;246:265–72. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2461062097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Godoy MC, Naidich DP. Subsolid pulmonary nodules and the spectrum of peripheral adenocarcinomas of the lung: Recommended interim guidelines for assessment and management. Radiology. 2009;253:606–22. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2533090179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brenner DJ. Radiation risks potentially associated with low-dose CT screening of adult smokers for lung cancer. Radiology. 2004;231:440–5. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2312030880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Aalst CM, van Klaveren RJ, van den Bergh KA, Willemsen MC, de Koning HJ. The impact of a lung cancer computed tomography screening result on smoking abstinence. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:1466–73. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00035410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]