Abstract

Objective

To screen for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in primary care patients 7–16 months after 9/11 attacks and to examine its comorbidity, clinical presentation and relationships with mental health treatment and service utilization.

Method

A systematic sample (n = 930) of adult primary care patients who were seeking primary care at an urban general medicine clinic were interviewed using the PTSD Checklist: the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) Patient Health Questionnaire and the Medical Outcome Study 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12). Health care utilization data were obtained by a cross linkage to the administrative computerized database.

Results

Prevalence estimates of current 9/11-related probable PTSD ranged from 4.7% (based on a cutoff PCL-C score of 50 and over) to 10.2% (based on the DSM-IV criteria). A comorbid mental disorder was more common among patients with PTSD than patients without PTSD (80% vs. 30%). Patients with PTSD were more functionally impaired and reported increased use of mental health medication as compared to patients without PTSD (70% vs. 18%). Among patients with PTSD there was no increase in hospital and emergency room (ER) admissions or outpatient care during the first year after the attacks.

Conclusions

In an urban general medicine setting, 1 year after 9/11, the frequency of probable PTSD appears to be common and clinically significant. These results suggest an unmet need for mental health care in this clinical population and are especially important in view of available treatments for PTSD.

Keywords: Primary care, Posttraumatic stress disorder, 9/11 attacks

1. Introduction

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, (9/11) were the most extreme acts of mass violence in recent US history. The physical devastation and the immediate economic burden were unprecedented. Community surveys found that between 4% [1] and 11% [2] of the adult US population and 11% [3] and 14% [4] of the adult New York City (NYC) population experienced loss due to the attacks of 9/11.

Nationwide surveys conducted after 9/11 have shown elevated levels of PTSD symptoms immediately after the attacks and a significant decrease over the following year [1,5]. The same pattern has been observed in NYC, where rates of PTSD declined from 7.5% one month after the attacks among people in lower Manhattan [3] to 2.3% four months, and 1.5% six months after 9/11 in the entire city area [4].

As compared with economically advantaged populations, disadvantaged immigrant populations are at increased risk for a range of mental disorders following exposure to trauma [6,7]. One to 2 months after the attacks, Hispanics drawn from a community sample living in NYC were at greater risk for PTSD than their non-Hispanic counterparts [3,8], confirming a number of pre-9/11 reports suggesting that Hispanics are at increased risk for PTSD following trauma exposure [9,10].

Low-income minority populations tend to disproportionately rely on primary care services for the provision of mental health care [11] and they are less likely than majority white populations to seek [12] or to receive treatment from mental health specialists [13,14].

In recent years, it has become increasingly evident that individuals with a history of trauma are likely to be seen in primary care [15–24]. In one primary care study, PTSD was the most common anxiety disorder, with 17% of the sample meeting criteria for PTSD [25]. In a second study, 38.6% of primary care patients referred for mental health services met criteria for PTSD [19]. In a study of affluent primary care outpatients, 11.8% of the sample met criteria for PTSD [21]. Primary care studies in Israel [18] and Taiwan [22] have found PTSD in 9% and 11% of the primary care patients, respectively.

Reports on use of mental health services and medications during the first year following 9/11 showed initial increase in service use in NYC followed by a decline [3,26,27]. No increase was detected in the use of psychotropic medications for most of the nation in the first 3 months after the attacks [28]. A study of the use of mental health services among war veterans with PTSD conducted 6 months after the attacks failed to demonstrate a significant increase in service utilization [29]. These reports were based on general community samples and on war veterans and may not apply to groups receiving services in primary care settings.

Despite advances in understanding the short-term psychological aftermath of trauma and loss, knowledge remains scarce concerning the long-term consequences of large-scale traumatic events in general and terror attacks in particular. We report results of the long-term impact of 9/11 attacks on systematic sample of low-income, mostly Hispanic patients attending an urban large primary care clinic in NYC. The specific aims of this study were to (1) estimate the current prevalence of probable current 9/11-related PTSD in an urban low-income general medicine practice; and (2) compare demographic characteristics, trauma exposure, clinical features, impairment and service use patterns of patients who screened positive for PTSD with those who did not; and (3) report on health functioning and impairment of screen-positive patients. We hypothesized that 9/11-related PTSD in this population would be significantly associated with psychiatric comorbidity, functional impairment and greater treatment use and service utilization.

2. Subjects and methods

2.1. Setting

The study was conducted at the Associates in Internal Medicine (AIM) clinic at the New York Presbyterian Hospital (Columbia University Medical Center), New York. AIM is the faculty and resident group practice of the Division of General Medicine at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia University. Each year AIM provides approximately 72,000 ambulatory visits to 18,000 patients from the surrounding northern Manhattan community.

2.2. Sample

A systematic sample of adult patients seeking primary care at the practice was invited to participate over the time period of 7–16 months after the 9/11 attacks. Participants’ recruitment has been described in detail elsewhere [30,31]. Patients were systematically approached to determine their eligibility on the basis of the position of the seat they freely selected in the waiting room. Every consecutive patient from the chairs in the back of the room to the front was screened for eligibility to obtain our final goal of about 1000 patients. Eligible patients were between 18 and 70 years of age, had made at least one prior visit to the practice, could speak and understand Spanish or English, were waiting for face-to-face contact with a primary care physician and were able to complete the survey. The survey was administered between December 2001 and January 2003 by bilingual research assistants who were present during the administration to assist participants in completion of the study questionnaire.

Of the 1118 patients who met eligibility criteria, 992 (88.7%) consented to participate, and of these, 930 (93.8%) provided detailed data with regard to their location on 9/11 and PTSD symptoms and therefore comprise the analytic sample.

All assessment forms were translated from English to Spanish and back-translated by a bilingual team of mental health professionals. The Spanish forms were reviewed and approved by the Hispanic Research and Recruitment Center at Columbia University Medical Center. The Institutional Review Boards of the Columbia University Medical Center and the New York State Psychiatric Institute approved the study protocol, and all participants gave informed written consent. Subject recruitment started on April 1, 2002, and was completed on January 16, 2003.

2.3. Measurements

2.3.1. Sociodemographic characteristics, trauma exposure and clinical status

All participants completed a history form to assess sociodemographic characteristics, pre-9/11 trauma and family psychiatric history. Type of exposure to the 9/11 disaster was determined by questions inquiring whether the patient was in lower Manhattan (below 14th Street) and knew somebody who was killed in the WTC attacks. Exposure to trauma prior to 9/11 was determined based on (1) a positive report of at least one trauma exposure from a modified version of the Life Events Scale [32] (bhappened to meQ or “witnessed it”); and (2) age of patient at which the “earliest exposure occurred” was at least 2 years earlier than the subject's current age, to verify that the exposure occurred prior to 9/11. The PTSD Check List-Civilian Version (PCL-C) [33] was used to screen for probable current 9/11-related PTSD. The PCL-C consists of 17 items corresponding to each symptom in DSM-IV PTSD criteria B, C and D. With regard to the WTC attacks, patients were asked, “In the last month, how much have you been bothered by” each symptom, with the following response choices: 1=not at all, 2=a little bit, 3=moderately, 4=quite a bit and 5=extremely.

The PCL is widely used to screen for PTSD and was shown to have good internal consistency, to be strongly correlated with other PTSD scales and to have high diagnostic efficiency [33–35]. Following Hoge et al. [36], we used two algorithms of PTSD to estimate prevalence. First, in accordance with the broad definition of the DSM-IV criteria [37], patients were considered as having probable PTSD if they endorsed at least one intrusion symptom, three avoidance symptoms and two hyperarousal symptoms with a rating of at least “moderately”; second, using a strict definition of PTSD, we used a cutoff score of 50 and over to define PTSD [2,33].

The survey forms included the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) [38] assess current symptoms of DSM-IV major depression (MD), panic disorder (PD), general anxiety disorder (GAD) and probable alcohol abuse/dependence. A probable drug abuse/dependence section patterned after the PRIME/MD PHQ alcohol use disorder assessment was also given. Subjects who reported being bothered for at least several days in the past week by “thoughts that you would be better off dead or thoughts of hurting yourself in some way” were classified as having suicidal ideation. Good agreement exists between PHQ diagnoses and independent mental health professional ratings for the diagnosis of any one or more PHQ disorder (kappa=.65; overall accuracy, 85%; sensitivity, 75%; specificity, 90%) [39].

Physical and mental health functioning were measured with the Physical and Mental Component Summary scores of the Medical Outcome Study 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) [40]. Impairment was evaluated with the 10-point self-rated social life and family life/home responsibilities subscales of the Sheehan Disability Scale (0=none, 1–3=mild, 4–6=moderate, 7–9=marked, 10=extreme) [41]. Significant impairment for each subscale was defined by a rating of 7 or greater. Because only 152 (20.0%) of the patients were gainfully employed, the work subscale of the Sheehan Disability Scale was not used in the following analyses. An assessment was conducted of the number of days in the past month that patients had missed work (paid or unpaid) or school. Work loss (yes or no) was based on missing 7 or more days in these activities. Self-report information was collected on mental health diagnoses of first-degree family member(s) including “bipolar disorder,” “manic depression,” “depression,” “anxiety/bad nerves” and/or “alcohol/drug use problems”. In addition, self-report information was collected on mental health treatment and hospitalization history. The latter section included information on past month use of psychotropic medication.

In order to examine whether patients with 9/11-related PTSD had increased utilization of services during the first year post 9/11, a cross-linkage to the Columbia University Medical Center's computerized database enabled the analysis of (1) visits (number and dates) to the primary care clinic and to the emergency room (ER; both general and psychiatric); and (2) hospitalizations (including admission and discharge dates) during this time frame.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Prevalence estimates of PTSD were based on both the broad DSM-IV criteria and the strict cutoff score of 50. PTSD was stratified by age, gender, race/ethnicity, immigrant status, marital status (defined as married or cohabiting vs. not), educational attainment, annual household income, employment status and family psychiatric history, and results showed similar patterns whether we used a strict or broad definition of PTSD. Therefore, we present only the results where the broad definition was used. The rates of MD, PD, GAD and alcohol use were based on diagnostic algorithms for the PRIME-MD PHQ [38,39]. A similar algorithm was developed for drug use disorder. Age was categorized into four groups: 18–44, 45–54, 55–64 and 65–70 years. Race/ethnicity was based on self-designated national origin and race. Patients were categorized as Hispanic if they identified their nation of origin as Spain or a Latin American country or if they chose to complete the study forms in Spanish. In addition, patients of Hispanic origin were divided into three groups: (1) Dominicans, (2) Puerto Ricans and (3) others. Non-Hispanic patients were divided into two groups: (1) Blacks and (2) Whites or others.

We restricted our analysis of post-9/11 health care utilization to patients who had received services at New York-Presbyterian Hospital at least 1 year prior to 9/11. Because of the small number of subjects with one or more ER visits or hospital admissions during the time frame examined, use of each of these services was coded as a binary outcome (1=any, 0=none).

Chi-square analysis was used to compare patients with and without PTSD on background variables that included demographic characteristics, presence of family psychiatric history and presence of any pre-9/11 trauma. Fisher's exact test was used when any cell had an expected count less than 5. Binary logistic regression was used to assess the effect of three types of trauma exposure on the likelihood of PTSD (1=present, 0=absent): proximity to the WTC on 9/11 (3=in the WTC or lower Manhattan, 2=in NYC, 1=in the NYC area, 0=outside the NYC area) and knowing someone killed by the WTC disaster (1=yes, 0=no). In subsequent analyses, we adjusted for the categorical variables sex, marital status, education, race/ethnicity, immigrant status, family psychiatric history and exposure to at least one traumatic event prior to 9/11. Logistic regression was also used to assess the effect of PTSD (1=present, 0=absent) on other binary outcomes (other mental disorders, impairment and work loss, self-reported mental health treatment). In subsequent analyses, we adjusted for sex, martial status, education, race/ethnicity, immigrant status, family psychiatric history, exposure to at least one traumatic event prior to 9/11, proximity to the WTC on 9/11 and knowing someone who was killed by the WTC disaster. Impairment and treatment outcomes were further adjusted for the presence of any current disorder other than PTSD (i.e., MDD, GAD, PD and/or alcohol or drug use disorder).

Linear regression was used to assess the effect of PTSD (1=present, 0=absent) on SF-12 scores expressed as unstandardized betas with 95% confidence intervals. Further analyses adjusted for the same variables as the logistic regressions described above had PTSD as the primary predictor.

We fit linear regression models to assess the effect of PTSD (1=present, 0=absent) on the number of outpatient visits made in the year after 9/11, controlling for the number of outpatient visits made in the year prior to 9/11. We used logistic regression to assess the effect of PTSD on the likelihood of ER visits in the year after 9/11 (1=any, 0=none), controlling for ER visits in the year prior to 9/11. Analysis of hospital admissions was analogous to that of ER visits.

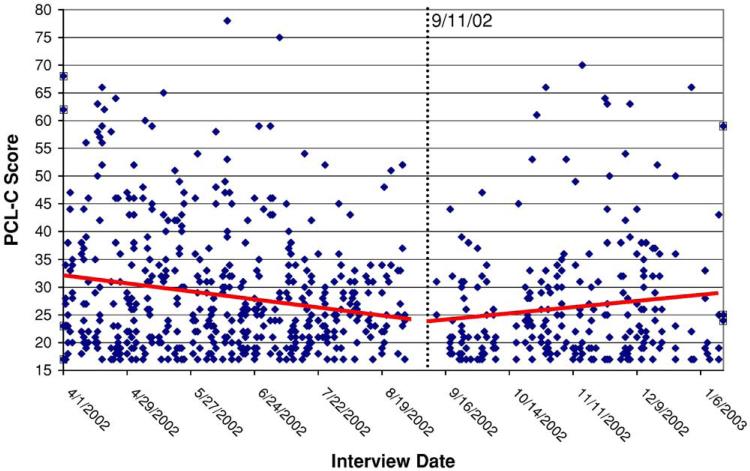

Exploratory analysis of PTSD rates during each month of the study suggested that from the start of the study until the 1-year anniversary of 9/11 (i.e., September 11, 2002), the likelihood of PTSD gradually receded and leveled off after the anniversary. However, the number of patients with PTSD in any 1- or 2-month period was too small to allow a sufficiently powered test of trend based on these rates. Therefore, we used piecewise linear regression to test the slope of PCL-C scores across time during two periods: between study start on April 1, 2002, and the 1-year anniversary of 9/11 on September 11, 2002; and between September 12, 2002, and study end on January 16, 2003. We further assessed whether the pre-anniversary and post-anniversary trends (i.e., the two slopes) were equivalent.

All tests were two-tailed, and significance was set at .05. Statistical analyses were conducted with SAS software version 9.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics and location during the attacks of 9/11, 2001

The sample was composed primarily of low-income, Hispanic patients, who were born outside of the United States and had little formal education. Females accounted for 69.6% of the patients; mean age was 51.2 (S.D.=11.9) years; 55.3% had not graduated from high school; 75.9% reported an annual family income of less than $12,000; 70.0% had never married or were currently separated, divorced or widowed, and only 20.0% of the patients reported they were paid workers. The percentage of the sample who had immigrated to the United States was 81.1%; 81.9% were of Hispanic origin, predominantly from the Dominican Republic (78.7%), followed by Puerto Rico (8.7%) and other Spanish-speaking countries (7.6%). Of the non-Hispanic patients, 73.2% were black. Notably, 38% of all patients reported a family psychiatric history and 62% reported pre-9/11 exposure to trauma.

The majority (78.2%) of the patients reported that they were in NYC during the 9/11 attacks and another 3.8% reported being in the WTC or in lower Manhattan below 14th Street. More than a quarter (27.1%) reported knowing someone who was killed during the 9/11 attacks.

3.2. PTSD and sociodemographic and exposure characteristics

Seven to 16 months after 9/11, the prevalence estimates of current 9/11-related probable PTSD in this sample ranged from 4.7% (based on a strict definition: PCL-C score of 50 or over) to 10.2% (based on DSM-IV criteria). Probable PTSD (hereafter referred to as PTSD) was significantly related to female gender, being born outside of the United States, not being married or cohabiting, and having a family history of psychiatric disorders and pre-911 trauma exposure (Table 1). No significant differences in PTSD were found between patients from Puerto Rico (3.0%; n =2/66) as compared to the Dominican Republic (5.7%; n =34/600) and to other Spanish-speaking countries (5.2%; n =3/58) ( P=.76; Fisher's exact test with df=2).

Table 1.

Prevalence rates of current 9/11-related probable PTSDa, by patient background characteristics

| Characteristic | % | χ2 (df=1) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 18–54 (n = 536) | 10.1 | 0.03 | .87 |

| 55–70 (n =394) | 10.4 | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female (n =647) | 11.6 | 4.4 | .04 |

| Male (n =283) | 7.1 | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic (n = 762) | 11.8 | 11.7 | .0006 |

| Non-Hispanic (n = 168) | 3.0 | ||

| Immigrant status | |||

| Born outside of the US (n =754) | 11.5 | 7.6 | .006 |

| Born in the US (n = 176) | 4.6 | ||

| Marital status | |||

| Separated/divorced, widowed or never married (n = 631) | 12.0 | 7.0 | .008 |

| Married/cohabiting (n =297) | 6.4 | ||

| Education level | |||

| Not a high school graduate (n =509) | 12.0 | 3.4 | .06 |

| High school graduate (n =412) | 8.3 | ||

| Annual household income | |||

| < $12,000 (n =700) | 10.7 | 0.9 | .36 |

| ≥ $12,000 (n =222) | 8.6 | ||

| Gainfully employed | |||

| No (n =744) | 10.4 | 0.1 | .79 |

| Yes (n =186) | 9.7 | ||

| Family psychiatric historyb | |||

| Yes (n =341) | 14.1 | 8.8 | .003 |

| No (n =558) | 7.9 | ||

| Any pre-9/11 traumac | |||

| Yes (n =474) | 15.2 | 28.9 | <.0001 |

| No (n = 285) | 2.8 |

Current 9/11-related PTSD was assessed with the PCL-C. Participants screen positive for current PTSD if they have at least one intrusion symptom, three avoidance symptoms and two hyperarousal symptoms. Symptoms are counted only if endorsed with a rating of 3 (indicating moderate severity) or higher.

First-degree family member(s) have been diagnosed with “bipolar disorder,“ “manic depression,” “depression,” “anxiety/bad nerves” and/or “alcohol/drug use problems”.

Data available for 759 subjects.

Mean PCL-C scores in patients interviewed 7–12 months after the attacks (n =491) significantly declined during this period (t =–4.38, P<.0001) (Fig. 1). Starting at the first year anniversary (9/11/2002), PCL-C scores (n =439) started to increase. We found a marginally positive time trend (t =1.92, P=.055). The two slopes (pre-anniversary and post-anniversary) were significantly different (t =3.13, P=.002).

Fig. 1.

Each dot represents a PCL-C score for a single participant plotted above the date of the interview. Separate lines of best fit are shown for two periods: (a) between study start on April 1, 2002, and the 1-year anniversary of 9/11 on September 11, 2002; and (b) between September 12, 2002, and study end on January 16, 2003.

Proximity to the epicenter of the attacks was not significantly associated with PTSD; however, the likelihood of PTSD tended to increase with closer proximity. Those outside of NYC on September 11, 2001, had a PTSD rate of 8.0% (16/201), those in NYC but not in lower Manhattan had a rate of 10.6% (73/692) and those in lower Manhattan or in the WTC itself had a rate of 17.1% (6/35) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Rates of current 9/11-related probable PTSD stratified by type of exposure to the WTC attacks

| Exposure variable | PTSD+ |

χ2 (df = 1) | P | Tests |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | Crude OR (95% CI)a | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | |||

| Proximity to WTC during 9/11 attacks | ||||||

| In the WTC or lower Manhattan (n = 35) | 6 | 17.1 | 2.0 (0.7–6.4) | 3.5 (0.9–14.0) | ||

| In New York City (n =692) | 73 | 10.6 | 1.1c | .30c | 1.2 (0.5–2.5) | 1.5 (0.6–3.8) |

| In the New York City area (n = 114) | 8 | 7.0 | 0.7 (0.3–2.1) | 1.1 (0.4–3.5) | ||

| Outside the New York City area (n = 87) | 8 | 9.2 | 1.0 (–) | 1.0 (–) | ||

| Loss in 9/11 and the Crash of Flight 587 | ||||||

| Know someone killed by the WTC disaster | ||||||

| Yes (n =252) | 43 | 17.1 | 17.6 | < .0001 | 2.5 (1.6–3.8) | 2.6 (1.6–4.4) |

| No (n = 677) | 52 | 7.7 | 1.0 (–) | 1.0 (–) | ||

Due to missing data, n =929–930.

OR is adjusted for sex; marital status (married/cohabiting vs. other); education (high school diploma: yes vs. no); race/ethnicity (Hispanic vs. black, non-Hispanic vs. white/other, non-Hispanic); born in the US (yes vs. no); family psychiatric history (yes vs. no); and exposure to at least one traumatic event prior to 9/11 (yes vs. no). Due to missing data, n =729–730.

Mantel–Haenszel test of linear trend.

PTSD was more common among patients who reported that they lost a person due to the attacks of 9/11 compared to those who did not experience such loss (Table 2).

To test whether indirect exposure to the attacks is associated with PTSD independent of family psychiatric history and history of trauma, we examined the prevalence of probable PTSD in patients who were not directly exposed to the attacks and reported no family psychiatric history or past trauma exposure (N=178). None of these participants screened positive for PTSD.

3.3. Psychiatric comorbidity

The majority of the patients with PTSD (68.4%) met criteria for a positive screen of one or more other mental disorder. The most frequent comorbid disorders were MD (57.9%) and GAD (33.7%) (Table 3). After adjustment for demographic and exposure covariates, PTSD remained strongly associated with each of the anxiety and mood disorders.

Table 3.

Mental health diagnoses and impairment/health status among patients with and without 9/11-related probable PTSD

| Outcome | PTSD+ (n =95) | PTSD– (n =835) | Tests | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | Crude OR (95% CI)a | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | |

| Mental disorder | ||||||

| Major depressive disorder | 55/98 | 57.9 | 146/829 | 17.6 | 6.4 (4.1, 10.0) | 5.3 (3.0, 9.3) |

| Panic disorder | 9/94 | 9.6 | 28/829 | 3.4 | 3.0 (1.4, 6.6) | 2.2 (0.8, 6.0) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 32/95 | 33.7 | 72/834 | 8.6 | 5.4 (3.3, 8.8) | 3.7 (2.0, 6.7) |

| Alcohol or drug use disorder | 10/94 | 10.6 | 62/798 | 7.8 | 1.4 (0.7, 2.9) | 1.4 (0.6, 3.3) |

| Any of the disorders above | 65/95 | 68.4 | 22/798 | 27.7 | 5.7 (3.6, 9.0) | 4.2 (2.4, 7.3) |

| Suicidal ideation | 17/95 | 17.9 | 27/830 | 3.3 | 6.5 (3.4, 12.4) | 1.6 (0.7, 3.7)c |

| Impairment | ||||||

| Social impairment | 50/85 | 58.8 | 101/815 | 12.4 | 10.1 (6.3, 16.3) | 5.2 (2.8, 9.8)d |

| Family life impairment | 35/89 | 39.3 | 92/822 | 11.2 | 5.1 (3.2, 8.3) | 2.7 (1.4, 5.1)d |

| Work loss | ||||||

| At least 7 days lost in past month | 46/63 | 73.0 | 142/535 | 26.5 | 7.5 (4.2, 13.5) | 4.6 (2.4, 8.9) |

| n | Mean±S.D. | n | Mean±S.D. | β (95% CI)e | Adjusted β (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health/functioning | ||||||

| SF-12 Mental Component Summary | 94 | 34.0±11.0 | 813 | 47.2±11.8 | –13.2 (–15.7, –10.7) | –6.2 (–8.7, –3.7)d |

| SF-12 Physical Component Summary | 94 | 34.2±9.8 | 813 | 40.4±11.5 | –6.2 (–8.7, –3.8) | –3.4 (–6.2, –0.6)d |

Mental disorders and suicidal ideation were assessed with the PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire. Impairment was assessed with the Sheehan Disability Scale; scores ≥ 7 (marked or extreme impairment) on the social and family life subscales were taken to indicate impairment. Health/functioning was assessed with SF-12.

Due to missing data, n =892–929, except for the “Work loss” outcome (n =598).

OR is adjusted for sex; marital status (married/cohabiting vs. other); education (high school diploma: yes vs. no); race/ethnicity (Hispanic vs. black, non-Hispanic vs. white/other, non-Hispanic) (to overcome estimation problems due to small cells, race/ethnicity was collapsed to “Hispanic” vs. “non-Hispanic” for the “Panic disorder” outcome); born in the US (yes vs. no); family psychiatric history (yes vs. no); proximity to the WTC on 9/11/01 (see Table 2 for description of the four levels); know someone killed by the WTC disaster (yes vs. no); and exposure to at least one traumatic event prior to 9/11 (yes vs. no). Due to missing data, n =677–726, except for the “Work loss” outcome (n = 519).

Adjusted also for the presence of major depression.

Adjusted also for the presence of at least one of the four listed mental disorders.

Expected score difference for those with PTSD (lower scores denote worse health).

Almost one fifth (17.9%) of the patients with PTSD, as compared with 3.3% of those without PTSD, reported suicidal ideation at least some days during the previous 2 weeks (Table 3). After controlling for the presence of MDD, demographic and exposure covariates, PTSD did not remain significantly associated with current suicidal ideation.

3.4. Impairment, functioning and health

Significant social and family life impairment were more common among patients with PTSD than those without it (Table 3). Impairment in both areas remained strongly associated with PTSD after adjusting for demographic and exposure covariates and the presence of any current mental disorder.

Work loss of 1 week or more in the past month was also more commonly reported by patients with PTSD than by those without and was significantly associated with PTSD after controlling for demographic and exposure covariates and the presence of any current mental disorder (Table 3). Finally, mental and physical health-related quality of life were worse for those with PTSD than for those without PTSD (Table 3). The group difference in SF-12 Mental Component Summary scores remained statistically significant after controlling for demographic and exposure covariates and the presence of any current comorbid mental disorder.

3.5. Mental health treatment and utilization of medical services

Half (50%) of the patients with PTSD reported taking a prescribed psychotropic medication in the last month, and the most commonly reported medications were antidepressants (48.9%). More than one third (39.8%) of the patients with PTSD reported receiving mental health treatment (Table 4). A history of previous mental health hospitalization was significantly more commonly reported by patients with PTSD than those without PTSD. In logistic regression models that adjusted for demographic and exposure covariates, PTSD remained significantly associated with the use of prescribed psychotropic medications and antidepressant drug and previous mental health hospitalization.

Table 4.

Mental health treatment in the past month, and visits in the first year after 9/11 attacks, among patients with and without 9/11-related probable PTSD

| Outcome | PTSD+ (n =95) | PTSD– (n = 835) | Tests | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | Crude OR (95% CI)a | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | |

| Mental health treatment (self-report) | ||||||

| Past month | ||||||

| Mental health treatment | 37/93 | 39.8 | 139/831 | 16.7 | 3.3 (2.1, 5.2) | 1.4 (0.8, 2.7) |

| Took a “prescribed medication” | 46/92 | 50.0 | 139/827 | 16.8 | 5.0 (3.2, 7.7) | 2.0 (1.1, 3.6) |

| Took an antidepressant drug | 45/92 | 48.9 | 124/822 | 15.1 | 5.4 (3.4, 8.5) | 2.4 (1.3, 4.3) |

| Took an antimanic drug | 3/91 | 3.3 | 13/818 | 1.6 | 2.1 (0.6, 7.6) | 2.5 (0.5, 11.7) |

| Took an antipsychotic drug | 8/91 | 8.8 | 23/818 | 2.8 | 3.3 (1.4, 7.7) | 1.1 (0.3, 3.8) |

| Lifetime | ||||||

| Psychiatric admission | 22/95 | 23.2 | 73/761 | 8.8 | 3.1 (1.8, 5.4) | 1.5 (0.7, 3.0) |

| Health services in the year after 9/11c | ||||||

| Emergency room visits, any | 23/49 | 46.9 | 180/441 | 40.8 | 1.3 (0.7, 2.4) | 0.7 (0.3, 1.5) |

| Hospital admissions, any | 6/49 | 12.2 | 89/441 | 20.2 | 0.6 (0.2, 1.4) | 0.3 (0.6, 1.2) |

| n | Mean±S.D. | n | Mean± S.D. | β (95% CI)d | Adjusted β (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health services in the year after 9/11 | ||||||

| Primary care visits | 49 | 7.5±4.4 | 441 | 7.6±5.5 | –0.1 (–1.3, +1.1)e | –0.1 (–1.5, +1.3)e |

Due to missing data, n = 909–929 for the “Mental health treatment (self-report)” outcomes, and n =490 for the “Health services in the year after 9/11” outcomes.

Odds ratios are adjusted for sex; marital status (married/cohabiting vs. other); education (high school diploma: yes vs. no); race/ethnicity (Hispanic vs. black, non-Hispanic vs. white/other, non-Hispanic); born in the US (yes vs. no); the presence of at least one other current mental disorder (MDD, GAD, panic disorder and/or “alcohol or drug use disorder”) (yes vs. no); family psychiatric history (yes vs. no); proximity to the WTC on 9/11/01 (see Table 2 for description of the four levels) (to overcome estimation problems due to small cells, proximity was omitted from analyses with the “antipsychotic drug” and “antimanic drug” outcomes); know someone killed by the WTC disaster (yes vs. no); and exposure to at least one traumatic event prior to 9/11 (yes vs. no). Due to missing data, n = 690–701 for the “Mental health treatment (self-report)” outcomes, and n = 358 for the “Health services in the year after 9/11” outcomes.

Visit data are presented for subjects who were locatable in the computerized medical records database and who were found to have made at least one visit (outpatient, emergency and/or inpatient) prior to September 11, 2000, i.e., a year prior to the 9/11 disaster.

Expected difference in number of visits for those with PTSD.

Adjusted also for service use during the 12 months prior to the 9/11 attacks: for emergency room visits, any (yes vs. no); for hospital admissions, any (yes vs. no); and for outpatient visits, the number of visits.

9/11-related current PTSD was not associated with making an ER visit, being admitted to a hospital or the number of outpatient visits made during the 12-month post-9/11 period, in either the crude or adjusted analyses.

4. Discussion

Prevalence estimates of probable current 9/11-related PTSD in this sample ranged from 4.7% (based on a PCL-C score of 50 or above) to 10.2% (based on DSM-IV criteria). This range of estimated prevalence is higher than previously reported 6 months after 9/11 in NYC (1.5%) [4] and may be related to family psychiatric history and extensive exposure to pre-9/11 trauma, as well as to the immigrant and marital status of this population. In a community survey in NYC conducted 6 months after 9/11, the prevalence of PTSD was the highest (15.1%) among participants who experienced four or more lifetime stressors before 9/11 [4]. In our clinical sample, nearly 6 in 10 patients reported pre-9/11 trauma, and the rate of probable PTSD was significantly associated with exposure to pre-9/11 trauma. These findings are consistent with both community and clinical studies conducted before 9/11 [3,4,6,7,42–47].

While community studies in NYC [4] suggested a rapid decline and diminished rates of PTSD over the 6 months after the 9/11 attacks, our findings suggest that a significant proportion of this sample of NYC residents seeking primary care continued to have PTSD associated with substantial functional impairment 7–16 months after the attacks. Similar to the pattern observed in previous studies [1,4], our findings indicate a steady decline in the prevalence of PTSD over time, but notably, starting at the 1-year anniversary (9/11/2002) an upward trend in PCL-C scores was observed. This finding might reflect the so-called anniversary reaction, possibly related to the massive media coverage of the 9/11 events around the 1-year anniversary. The graphic descriptions, as well as detailed accounts of bereaved, evacuees, rescue workers and witnesses, might have activated or exacerbated PTSD symptoms in a significant number of individuals to either meet full diagnostic criteria in persons with a partial syndrome or trigger a new onset of PTSD. Further research is needed to clarify this finding.

Nationwide post-9/11 surveys suggest that indirect exposure to large-scale disasters might be associated with PTSD [1,2]. Our findings suggest that indirect exposure to the 9/11 attacks by itself was not associated with PTSD among patients who did not report pre-9/11 trauma and/or family psychiatric history. These results are consistent with disaster [7,43,46] and combat [47] studies documenting a relationship between trauma severity and PTSD.

Previous research at our clinic [48] has found high rates of MD and suicidal ideation. The current study found that a majority of participants with current probable PTSD had comorbid psychiatric disorder (68%) [49]. PTSD is associated with significant disability [50]. Many patients with chronic PTSD are not able to function in work and social activities, and they remained impaired despite maintenance treatment [51]. Our study demonstrates that primary care patients who screen positive for PTSD also experience significant disability in health, social and family functioning even after adjusting for the presence of exposure to trauma both before and during 9/11 and for other mental disorders.

Findings from the general population and war veterans suggest that visits to mental health professionals and use of psychiatric drugs decreased over time following 9/11 [3,26,27] or were unchanged [28,29]. Findings from this primary care population suggest that while self-reported use of medication increased after 9/11, the administrative records from this population indicate that PTSD is not associated with increased hospital admissions, emergency care use or out-patient care during the first year after the 9/11 attacks. The accuracy of these self-reports remains uncertain. Adults who report high levels of distress tend to report more mental health care than can be confirmed in administrative records [52,53].

Taken together, these findings highlight the specific needs for health care associated with post-disaster psycho-pathology among low-income Hispanic primary care patients. Because poor and ethnic populations tend to avoid seeking [12] or receiving treatment from mental health specialists [13,14] and disproportionately rely on primary care services for the provision of their mental health care [11], our findings underscore the importance of developing post-trauma care for affected individuals in general medical practices, especially when disasters strike minority communities [54].

4.1. Limitations

The study has several limitations. First, self-report of traumatic exposure is subject to recall bias, and it is possible that some participants may have attributed PTSD symptoms to the 9/11 attacks that were actually more closely related to other traumatic events. Second, the computerized database that recorded the utilization of services of the patients in this sample is limited to Columbia University Medical Center and so does not capture services delivered by other providers. It is possible that study patients with PTSD sought primary care in other nonaffiliated clinics. However, a previous study of this population demonstrated that only 9% of the patients attended other clinics over 6 months of follow-up [55], suggesting that people in this community tend to be highly dependent on the university hospital services. It is therefore likely that the medical records provide a reasonable index of total medical care use. Third, because our survey assessed current PTSD, it potentially missed patients who had 9/11-related PTSD that resolved prior to our survey. Fourth, the positive temporal trend in 9/11-related PTSD symptom severity following the anniversary of the attacks might represent other changes in the community that might increase primary care utilization among the sample. Finally, because the study was undertaken in an urban general medical practice serving a low-income population, the findings may not be generalizable to primary care settings with different populations [56,57].

Our findings have clinical implications. Primary care patients from vulnerable populations, present in general medical settings, are likely to experience PTSD associated with long-term and clinically significant symptoms and functional impairment following large-scale events [15–24]. In order to recognize PTSD in primary care, physicians and mental health professionals need to obtain a detailed trauma history [54,58]. Timely interventions in patients who have been detected with exposure to trauma and manifest with PTSD symptoms in the aftermath of large-scale disasters may help to prevent long-term, chronic morbidity.

Footnotes

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, 1RO1 MHO72833-01; Yuval Neria), the National Association of Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD; Yuval Neria), Eli Lilly & Company (Myrna Weissman) and Glaxo Welcome (Adriana Feder).

Presented in part at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, May 3, 2004, New York, NY.

References

- 1.Silver RC, Holman EA, McIntosh DN, Poulin M, Gil-Rivas V. Nationwide longitudinal study of psychological responses to September 11. JAMA. 2002;288:1235–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.10.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlenger WE, Caddell JM, Ebert L, et al. Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: findings from the National Study of Americans’ Reactions to September 11. JAMA. 2002;288:581–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, et al. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:982–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa013404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galea S, Vlahov D, Resnick H, et al. Trends of probable post-traumatic stress disorder in New York City after the September 11 terrorist attacks. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158:514–24. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuster MA, Stein B, Jaycox LH, et al. A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. N Eng J Med. 2001;345:1507–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200111153452024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:748–66. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Norris F, Friedman M, Watson P, Byren C, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 2002;65:207–39. doi: 10.1521/psyc.65.3.207.20173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galea S, Vlahov D, Tracy M, Hoover DR, Resnick H, Kilpatrick D. Hispanic ethnicity and post-traumatic stress disorder after a disaster: evidence from a general population survey after September 11, 2001. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:520–31. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ortega AN, Rosenheck R. Posttraumatic stress disorder among Hispanic Vietnam veterans. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:615–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pole N, Best SR, Metzler T, Marmar CR. Why are Hispanics at greater risk for PTSD? Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2005;11:144–61. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.11.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olfson M, Broadhead WE, Weissman MM, et al. Subthreshold psychiatric symptoms in a primary care group practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:880–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830100026004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard KI, Cornille TA, Lyons JS, Vessey JT, Lueger RJ, Saunders SM. Patterns of mental health service utilization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53:696–703. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830080048009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallo JJ, Marino S, Ford D, Anthony JC. Filters on the pathway to mental health care: II. Sociodemographic factors. Psychol Med. 1995;25:1149–60. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leaf PJ, Bruce ML, Tischler GL, Freeman DH, Jr, Weissman MM, Myers JK. Factors affecting the utilization of specialty and general medical mental health services. Med Care. 1998;26:9–26. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruce SE, Weisberg RB, Dolan RT, et al. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care patients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:211–7. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v03n0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickinson LM, deGruy FV, III, Dickinson WP, Candib LM. Complex posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence from the primary care setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1998;20:214–24. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(98)00021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McQuaid JR, Pedrelli P, McCahill ME, Stein MB. Reported trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder and major depression among primary care patients. Psychol Med. 2001;3:1249–57. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taubman-Ben-Ari O, Rabinowitz J, Feldman D, Vaturi R. Post-traumatic stress disorder in primary-care settings: prevalence and physicians’ detection. Psychol Med. 2001;31:555–60. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samson AY, Bensen S, Beck A, Price D, Nimmer C. Posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care. J Fam Pract. 1999;48:222–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schonfeld WH, Verboncoeur CJ, Fifer SK, Lipschutz RC, Lubeck DP, Buesching DP. The functioning and well-being of patients with unrecognized anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 1997;43:105–19. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(96)01416-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stein MB, McQuaid JR, Pedrelli P, Lenox R, McCahill ME. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the primary care medical setting. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2000;22:261–9. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(00)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang YK, Yeh TL, Chen CC, et al. Psychiatric morbidity and posttraumatic symptoms among earthquake victims in primary care clinics. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:253–61. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00022-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holman EA, Silver RC, Waitzkin H. Traumatic life events in primary care patients: a study in an ethnically diverse sample. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:802–10. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Magruder KM, Frueh BC, Knapp RG, et al. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in Veterans Affairs primary care clinics. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:169–79. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fifer SK, Mathias SD, Patrick DL, Mazonson PD, Lubeck DP, Buesching DP. Untreated anxiety among adult primary care patients in a health maintenance organization. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:740–50. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950090072010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boscarino JA, Galea S, Adams RE, Ahern J, Resnick H, Vlahov D. Mental health service and medication use in New York City after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attack. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:274–83. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boscarino JA, Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, Vlahov D. Psychiatric medication use among Manhattan residents following the World Trade Center disaster. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16:301–6. doi: 10.1023/A:1023708410513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Druss BG, Marcus SC. Use of psychotropic medications before and after Sept. 11, 2001. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1377–83. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenheck R, Fontana A. Use of mental health services by veterans with PTSD after the terrorist attacks of September 11. Am J Psychiatry. 2003:1684–90. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weissman M, Neria Y, Das A, et al. Gender differences in PTSD among primary care patients following the World Trade Center attacks. Gender Medicine. 2005;2:76–7. doi: 10.1016/s1550-8579(05)80014-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Das AK, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA. 2005;293:956–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.8.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–60. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD checklist: reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; Boston: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Check List (PCL). Behav Res Ther. 1996;34:669–73. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forbes D, Creamer M, Biddie D. The validity of the PTSD Check-List as a measure of symptomatic change in combat-related PTSD. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39:977–86. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(00)00084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, et al. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV) 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington (DC): 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: The PRIME-MD 1000 Study. JAMA. 1994;272:1749–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ware J, Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leon AC, Shear MK, Portera L, Klerman GL. Assessing impairment in patients with panic disorder: the Sheehan Disability Scale. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1992;27:78–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00788510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.North CS, Nixon SJ, Shariat S, et al. Psychiatric disorders among survivors of the Oklahoma City bombing. JAMA. 1999;282:755–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.8.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bromet E, Sonnega A, Kessler RC. Risk factors for DSM-III-R posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:353–61. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neria Y, Bromet EJ, Sievers S, Lavelle J, Fochtmann LJ. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in psychosis: findings from a first-admission cohort. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:246–51. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoven CW, Duarte CS, Lucas CP, et al. Psychopathology among New York City public school children 6 months after September 11. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:545–51. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Solomon Z, Neria Y, Ohry A, Waysman M, Ginzburg K. PTSD among Israeli former prisoners of war and soldiers with combat stress reaction: a longitudinal study. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:554–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.4.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olfson M, Shea S, Feder A, Fuentes M, Nomura Y, Gameroff M, et al. Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders in an urban general medicine practice. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:876–83. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neria Y, Bromet EJ. Comorbidity of PTSD and depression: linked or separate incidence. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48:878–80. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yehuda R. Post-traumatic stress disorder. N Eng J Med. 2002;346:108–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra012941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Marshall RD, Cloitre M. Maximizing treatment outcome in PTSD: an empirically-informed rationale for combining psychotherapy with pharmacotherapy. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2000;2:335–40. doi: 10.1007/s11920-000-0078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rhodes AE, Fung K. Self-reported use of mental health services versus administrative records: care to recall. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:165–75. doi: 10.1002/mpr.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rhodes AE, Lin E, Mustard CA. Self-reported use of mental health services versus administrative records: should we care? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2002;11:125–33. doi: 10.1002/mpr.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lecrubier Y. Posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care: a hidden diagnosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mundinger MO, Kane RL, Lenz ER, et al. Primary care outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2000;283:59–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Blazer D, George LK, Landerman R, et al. Psychiatric disorders. A rural/urban comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:651–6. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790300013002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bruce ML, Takeuchi DT, Leaf PJ. Poverty and psychiatric status. Longitudinal evidence from the New Haven Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:470–4. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810290082015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Engel CC. Improving primary care for military personnel and veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder — the road ahead. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2005;27:158–60. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]