Abstract

Health-related quality of life (HRQL) has been assessed in various lung transplantation (LT) investigations but never analyzed systematically across multiple studies. We addressed this knowledge gap through a systematic literature review. We searched the PubMed, CINAHL, and PsychInfo databases for publications from 1/1/1983-12/31/2011. We performed a thematic analysis of published studies of HRQL in LT. Using a comparative, consensus-based approach, we identified themes that consistently emerged from the data, classifying each study according to primary and secondary thematic categories as well as by study design. Of 749 publications initially identified, 73 remained after exclusions. Seven core themes emerged: 1) Determinants of HRQL; 2) Psychosocial factors in HRQL; 3) Pre- and post-transplant HRQL comparisons; 4) Long-term longitudinal HRQL studies; 5) HRQL effects of therapies and interventions; 6) HRQL instrument validation and methodology; 7) HRQL prediction of clinical outcomes. Overall, LT significantly and substantially improves HRQL, predominantly in domains related to physical health and functioning. The existing literature demonstrates substantial heterogeneity in methodology and approach; relatively few studies assessed HRQL longitudinally within the same persons. Opportunity for future study lies in validating existing and potential novel HRQL instruments and further elucidating the determinants of HRQL through longitudinal multidimensional investigation.

Keywords: end-stage lung disease, clinical outcomes, health outcomes, lung transplantation, patient outcome, quality of life, quality of life research, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Lung transplantation (LT) aims not merely to extend recipient survival, but also to improve health-related quality of life (HRQL). It is well-appreciated that patients with advanced lung disease awaiting LT suffer from poor HRQL.1-11 While in-depth studies of survival are routine, analyses of HRQL outcomes following LT are relatively infrequent. Among other chronic diseases, HRQL is recognized as a key patient-centered outcome (PCOs). Although this presumably true in LT as well, PCOs have not been an emphasized area of the research agenda to date and the literature on this subject thus remains fragmented.

An improved understanding of HRQL has important clinical and research implications. It could provide patients and clinicians with estimates of the magnitude and durability of improvements in HRQL that might be expected from LT, identify HRQL determinants that may be targets for intervention, and lay the foundation needed to incorporate HRQL into clinical decision-making.

In this systematic review, we aimed to analyze studies of HRQL in LT in order to distill the unifying themes embedded within the existing biomedical literature. In characterizing the current state of knowledge, we also sought to identify knowledge gaps that provide opportunity for future study.

METHODS

Search Strategy

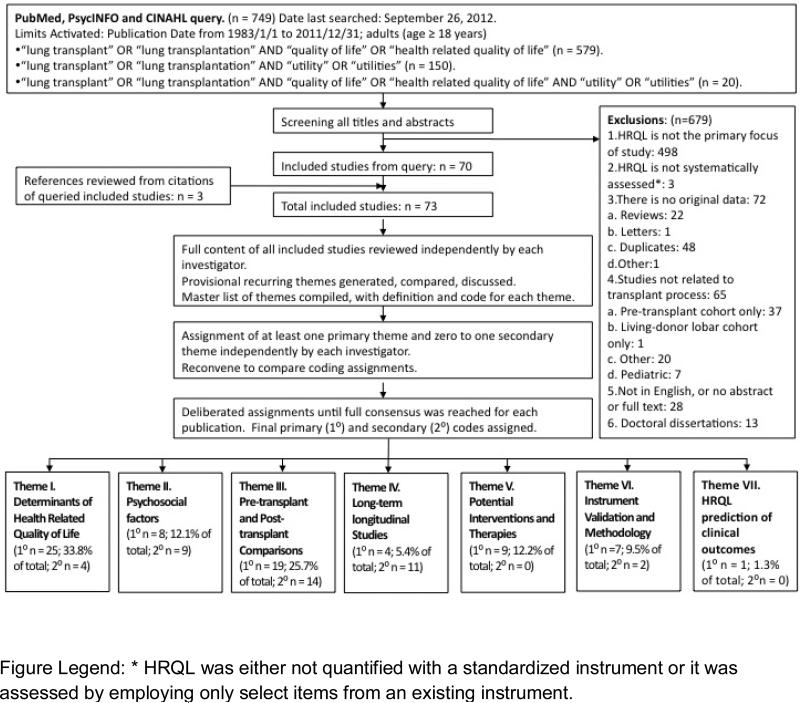

We queried the PubMed, CIHNAL, and PsychINFO databases using the search terms “(health-related) quality of life” “utility/ies”, and “lung transplant/ation”, limited to studies in adults (age≥18), and published from1/1/1983-12/31/2011. We identified 749 potentially relevant citations and, after exclusions, 73 publications were ultimately retained (one of these in abstract form only) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Systematic review and thematic analysis process.

Data Analysis

We utilized thematic analysis, a qualitative mode of scientific inquiry that systematically analyzes textual data12. A central aspect of thematic analysis is its inductive and iterative nature, which is not bound to any philosophic tradition or theoretical paradigm.12 Study content was iteratively reviewed and analyzed by three investigators (J.S, J.C.,H.C.).12 First, a provisional list of recurring themes was developed by each investigator. These were compared and discussed. Themes deemed similar or overlapping were merged; those encompassing conceptually distinct themes were split. A master thematic list was coded; definitions for each theme were developed to ensure consistency among investigators (Table 1). Using the listed themes, each investigator independently assigned a primary thematic code to each study. For some studies, a secondary code also was assigned. Investigators reconvened to compare coding assignments; discrepancies in coding were resolved by consensus ultimately resulting in the 73 studies being categorized according to the overarching themes that emerged (Table 1).

Table I.

Unifying Themes and Categorized Studies

| Theme | Studies fulfilling Primary Theme (N (%) of 73 total) | Primary thematic code | Secondary Thematic code | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Determinants of HRQL | 24 (32.9%) | Anyanwu 2001Gerbase 2008 Gerbase 2005 Girard 2006 Hummel 2001 Irani 2010 Kugler 2005 Kugler 2007 Kunsebeck 2007 Langer 2009 Littlefield 1996 Lutogniewska 2010 |

Pinson 2000 Ricotti 2006 Rodrigue 2006 Singer 2005 Smeritschnig 2005 Tegtbur 2004 Van Den 2000 Vasiliadis 2006 Vermeulen 200428 Vermeulen 200432 Vermeulen 2007 Vermeulen 2008 |

Eskander2011 Ortega 2009 Ramsey 1995 Stilley 1999 |

|

| 2. Psychosocial aspects of HRQL | 8 (10.9%) | Archonti 2004 De Vito Dabbs 2003 Goetzmann 2008 Kollner 2002 |

Kurz 2001 Limbos 2000 Nilsson 2011 Stilley 1999 |

Cohen 1998 Festle 2002 Feurer 2004 Girard 2006 Irani 2006 |

Myaskovsky 2006 Santana 2009 Smeritschnig 2005 Vermeulen 200428 |

| 3. Pre- and post-transplant HRQL comparisons | 20 (27.4%) | Beilby 2003 Busschbach 1994 Caine 1991 Cohen 1998 Eskander 2011 Gross 1995 Kugler 2004 Lanuza 2000 Limbos 1997 MacNaughton 1998 |

O'Brien 1988 Ortega 2009 Pirson 2011 Ramsey 1995 Rodrigue 2005 Santana 2009 Shih 2002 Singer 2009 TenVergert 1998 TenVergert 2001 |

Anyanwu 2001 Archonti 2004 Irani 2010 Kugler 2010 Kurz 2001 Limbos 2000 Santana201061 Stavern 2000 |

Vasiliadis 2006 Vermeulen 2003 Vermeulen 2008 Pinson 2000 Rodrigue 2006 Vermeulen 2004 |

| 4. Longitudinal studies of HRQL in the post-transplant period | 4 (5.5%) | Kugler 2010 Myaskovsky 2006 Rutherford 2005 |

Vermeulen 2003 | Gerbase 2008 Gerbase 2005 Gross 1995 Ihle 2011 Kugler 2004 O'Brien 1988 |

Van Den 2000 Vermeulen 2005 Vermeulen 2007 TenVergert 1998 TenVergert 2001 |

| 5. Impact of therapies and other interventions on HRQL | 9 (12.3%) | De Vito Dabbs 2009 Ihle 2011 Irani 2006 Matthees 2001 Munro 2009 |

Robertson 2011 Santana 201051 Silvertooth 2004 Vivodtzev 2011 |

||

| 6. HRQL instrument Validation and Methodology | 7 (9.6%) | Festle 2002 Feurer 2004 Lobo 2004 |

Santana 201061 Stavern 2000 Vasiliadis 2005 Vermeulen 2005 |

Singer 2009 Lanuza 2000 |

|

| 7. HRQL prediction of clinical outcomes | 1 (1.4%) | Squier 1995 | |||

RESULTS

Among 73 publications, 7 themes emerged (Table 1): 1) Determinants of HRQL; 2) Psychosocial factors in HRQL; 3) Pre- and post-transplant HRQL comparisons; 4) Longitudinal studies of HRQL in the post-transplant period; 5) HRQL in relation to therapies or other interventions; 6) HRQL instrument validation and methodology; 7) HRQL prediction of clinical outcomes. For 40 studies a secondary thematic category was assigned.

Determinants of HRQL

The majority of studies (primary theme, n=24; secondary theme, n=4) assessed determinants of HRQL. Exclusive of psychosocial factors (categorized separately), bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) and transplant type were the determinants most commonly addressed. Others included: pre-transplant diagnosis, immunosuppressant adverse effects, dyspnea, allograft function, pain, and acute rejection. Notably, few studies employed multivariate adjustment,13-23 making confounding difficult to assess.

Studies consistently observed that BOS is strongly associated with poorer HRQL.13, 20, 21, 23-28 This was consistent across HRQL instruments, including both respiratory-specific measures (St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire [SGRQ])24, 26 and generic measures (Quality of Life Profile for Chronic Diseases13, 12- or 36-item Short Form [SF-12 or SF-36]25,26, Nottingham Health Profile [NHP]17, 27, 28) and utilities (Standard gamble)21. The impact of BOS was greatest in HRQL domains relating to physical functioning, energy, and mobility. Several of these studies included overlapping cohort participants; most were cross-sectional, comparing patients with and without BOS. Only two studies (total n=51) assessed change in HRQL longitudinally as BOS developed.27, 28

Six studies evaluating transplant type yielded mixed results. The findings of single-, bilateral- and heart-lung transplantation comparisons, although equivocal, suggested better outcomes among bilateral- and heart-lung recipients compared to single LT. Two demonstrated higher health-utilities (5-Dimensional EuroQOL [EQ-5D] or Standard Gamble) among bilateral and heart-lung recipients.21, 29 Underscoring the heterogeneity of findings, one study observed that single-LT recipients reported greater pain and worse HRQL than recipients of bilateral-LT18, whereas another reported the opposite22 (both used the SF-36). The only study employing a respiratory-specific instrument (SGRQ) demonstrated non-statistically significantly better HRQL in bilateral-LT versus single-LT.7 In studies among various organ recipients (one including lung, kidney and liver recipients30 and another lung, heart and liver recipients14), LT recipients manifested the greatest magnitude post-transplant improvement in HRQL in most domains of the SF-36.30

While few studies examined the impact of pre-LT diagnosis on HRQL, four suggested that cystic fibrosis, compared to other diagnoses, is associated with better post- vs. pre-LT HRQL..4, 22, 26, 31, 32 Other less-studied factors that may impact post-LT HRQL include side-effects related to immunosuppression26, 33, dyspnea20, 34, energy/mobility23, 27, 28, pain18, 20, 35, rejection13, 20, exercise tolerance36, infections,13 and olfactory performance19.

Psychosocial Factors

Psychosocial factors emerged as the primary theme in eight studies and a secondary theme in nine others. Most of these focused on depression or anxiety symptoms, observing that many patients manifested symptoms both before and after LT.16, 37-39 Symptoms were more likely post-LT when pre-LT depression or anxiety were present6, 16 These studies employed a broad range of psychosocial measures, including the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (n=10), Beck Depression Inventory (n=5), Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (n=8), and State Trait Anxiety Inventory (n=11).

Psychosocial factors other than depression and anxiety have also been investigated40-46. These included symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder44, burden on relationships37, adjustment to illness,41 feeling of responsibility to donors and caregivers42, low self-esteem38, decreased sexual drive38, and perceived threat of risk of graft rejection48. Few of these studies, however, analyzed such factors beyond identifying an association between them and HRQL or describing the extent of the attribute observed. A notable exception was a longitudinal study of 105 patients in which greater optimism, social support, and perceived positive relationships predicted higher HRQL, while avoidant coping strategies predicted poorer HRQL.46 Similar cross-sectional relationships have also been observed in two other studies.46, 47, 49

Pre- and Post-transplant Comparisons

Thirty-four studies (primary theme, n=20; secondary theme, n=14) compared HRQL in relation to LT status (i.e., pre- vs. post-LT). Many (n=13) compared wait-listed patients to others that had undergone LT 11, 19, 22, 29, 37, 38, 45, 50, 51; others (n=14) did employ a true longitudinal design, assessing the same patients before and after LT. 17, 30, 31, 39, 52-56 Of these, eleven studied cohorts of relatively modest size (n=22-66).3, 4, 6, 30, 39, 52, 54-58 A larger 5-year prospective cohort study obtained repeated measures of HRQL before and after LT in 88 patients who survived the first post-LT year.53 Of the 88, 48 contributed data at 5-years post-LT. Notably, it is unclear whether this study represented an overlapping cohort from an earlier report.52 Another study (abstract only) assessed health-utilities in 207 patients before and after LT.31 A single study determined that HRQL pre-LT was not predictive of post-LT mortality.17

Importantly, the HRQL instruments employed varied greatly. The SF-36 was the most frequently employed generic instrument.3, 6, 9, 11, 22, 30, 37, 38, 50, 52-54, 59 Other generic instruments included the Nottingham Health Profile (NHP)1, 4, 5, 17, 28, 55, 57, 58, 60 and health-utility indices, including the EQ-5D1, 29, 61, Standard Gamble1, 4, 21, 56, 62, Health Utilities Index (HUI)39, 51, 61, Index of Well Being5, 17, 27, 28, 32, 55, 58, 63, and Visual Analog Scale7, 20, 24, 38, 56, 64-66. The only frequently employed respiratory-specific instrument was the SGRQ.7, 11, 20, 24, 26, 34, 52, 56, 67

Despite instrument heterogeneity, the impact of LT on HRQL was consistently demonstrated to be both significant and substantial. The largest changes were typically observed in physical health and functioning domains. As expected, improvements in these domains paralleled improvements in forced expiratory volume in 1-second and walk distance11, 54, 59, 68. Despite large improvements, residual HRQL impairments remained post-LT in comparison to normative population values. These impairments tended to affect physical health and functioning domains9, 15, 20, 26, 30, 42, 50, 51, 54, 64, 69-71. Further, improvements in HRQL were not uniform and sometimes spared other domains..3, 4, 9, 11, 30, 38 For example, pain was unchanged or possibly worsened soon after transplant11, 15, 30, 37, 52, 55, although it was observed to improve over time39, 52. In contrast to physical health, changes in emotional well-being and mental health domains were heterogeneous, frequently demonstrating small or non-significant improvements2, 3, 6, 9, 11, 22, 42, 52, 53, 59, 72,52, 54, 68. Post-transplant scores in these domains were comparable with normative population values 9, 14, 15, 20, 26, 42, 50, 53, 54, 64, 70, 71. In studies of depression and anxiety, depression appeared to decrease post-LT, whereas an effect on anxiety was not observed19, 39. In an atypical study design combining archival data with a contemporary cross-sectional analysis, pre-transplant psychopathology (anxiety, depression) was associated with poorer HRQL (SF-36), disturbed sleep, and poorer mental health.6

Long-term Longitudinal Studies

A small number of relatively recent studies report long-term HRQL assessed longitudinally (primary theme n=4, secondary theme n=11). HRQL tends to improve substantially within the first 6-months post-LT and continues to do so through the first year.46, 52 Thereafter, the trajectory of HRQL is less clear. In some studies, HRQL stabilized after the first post-transplant year 5, 53, 58, whereas in others, it declined7, 55, 71. Nonetheless, in those studies observing a decline, the impairment never reached levels observed before transplant. Declines were associated with the onset of BOS and comorbid illnesses.23, 24, 27, 53, 55, 58, 63, 71

A limited number of studies with a relatively small cumulative subject pool studied HRQL in patients surviving greater than three years post-LT.7, 23, 24, 27, 53, 55, 63, 67, 71, 73 Survivorship bias due to losses to follow-up makes interpreting these data difficult. Additionally, results from these studies vary depending on the analytic approach used.73 Only 175 of such “long-term” survivors have been included in the entire body of this literature.24, 53, 55, 63, 71 Two additional studies evaluated long-term survivors within larger cohorts, but the data are presented in ways that make it difficult to extract information on this subset. 7, 23

Potential Therapies and Interventions

Nine studies evaluated therapies or interventions. Six of these involved behavioral interventions.43, 65, 67, 72, 74, 75 Four studies employed randomized designs (RCT.)51, 67, 74, 76 One RCT assessed the impact of incorporating utilities (HUI-measure) into the post-transplant care of 213 subjects.51 Small improvements in patient-clinician communication and patient management were observed but improved health status (EQ-5D) was not. A separate RCT of 30 subjects studied a hand-held, computer-based device used to record, review, and report health data. Use of this device improved measures of self-care and HRQL (SF-36).74 A small RCT (reported in letter form) evaluated the impact of citalopram on HRQL.76 Non-randomized, uncontrolled studies have also evaluated pulmonary rehabilitation72, pet companionship43, and complementary and alternative medicine65 post-LT.

Instrument Validation and Methodology

Relatively few studies (primary theme n=7, secondary theme n=1) evaluated the psychometric performance and validity of HRQL instruments LT populations. The SF-36 and SGRQ demonstrated good internal consistency and discriminant validity.11, 41 Santana et al. evaluated HUI Mark-3 utility construct validity by comparing clinician-based predictions with observed correlations.51 They showed that the instrument performed largely in the expected manner. Other investigators have evaluated preference-based utilities.31, 77 Using the Standard Gamble, utilities are associated with “transplant-readiness” and improve post-LT. Interestingly, LT candidates can accurately estimate utilities post-LT, except in the setting of advanced BOS.

Only one study evaluated HRQL through qualitative methods.40 Descriptions of life post-LT were provided based on a collection of patient narratives. The study uncovered important factors not captured in the quantitative literature, such as mixed feelings of both gratitude and guilt for the donor and their family, “sacrificing” extra-pulmonary organ function (i.e., renal) to maintain allograft function, and a responsibility to make the most of a “second chance at life”.

HRQL prediction of clinical outcomes

A single study analyzed whether pre-transplant HRQL predicted survival both on the waiting list and after transplant. HRQL (Quality of Well-Being Scale [QWB]), was collected in 74 waitlisted subjects. Of these, 49 underwent LT. In the total cohort of waitlisted and transplanted subjects, subjects with upper median baseline QWB scores (higher HRQL) had significantly better survival than subjects with lower median scores. Although the statistical modeling included transplant status, other methodological limitations make it difficult to determine whether pre-transplant HRQL predicts survival post-transplant. Further, the survival models did not include covariates other than HRQL and transplant status raising the possibility of unmeasured confounding.78

DISCUSSION

This systematic review of 73 studies over three-decades of scholarship identifies important insights into HRQL relevant for clinicians and patients considering lung transplantation. Most importantly, the literature supports that LT results in clinically meaningful and significant improvements in HRQL for patients with advanced lung disease. This improvement is greatest in physical health and functioning domains. The largest improvement is observed within the first 6-months after LT, continuing up to one-year. After one-year, HRQL trajectories are less stable, being negatively affected by BOS and incident comorbidities. Although some heterogeneity exists, overall HRQL levels post-LT do not decline to pre-LT levels.

Nevertheless, LT recipients manifest substantial residual impairments in HRQL compared to population norms. Comparative data with other types of solid organ transplant, while limited, suggest that LT recipients may derive greater HRQL benefit. This benefit, however, is likely attributable to the extremely poor HRQL in pre-operative LT candidates.

While the insights provided in the existing literature are impressive, our search revealed limitations that provide opportunity for future research. First and foremost, despite its clinical primacy, HRQL remains understudied in the field of LT. Indeed, similar search criteria over the same time-period yielded 1131 articles published in cardiac transplantation, 1291 in liver, and 1689 in kidney. Poorer survival post-LT relative to other solid-organ transplants further underscores the importance of HRQL as a key clinical and research outcome. By accounting for HRQL, a substantial “net-benefit” could arguably be achieved from LT even when extended survival may not be clear. Indeed, just such a net-benefit was demonstrated in lung volume reduction surgery for emphysema.79 Notably, we employed a rather liberal approach in defining HRQL, including health utilities within our search. Health utility-based instruments quantitatively measure patient preferences for certain health states or outcomes. Health utilities, which capture degree of impairment, degree of bother, and willingness to undergo risk to reduce bother, offer an alternative means for measuring the health benefit of interventions80. Health-utilities are conceptually related to HRQL but are not wholly inter-changeable; in particular, the item content contained in utility-based instruments rarely reflect the multidimensional nature of HRQL. Had we excluded studies employing utilities, only 45 of 73 would have remained.

Analyzed thematically, it becomes clear that the available data are fragmented among investigations of a variety of clinical and psychosocial determinants with relatively sparse data on instrument validation. Other methodological limitations include incomplete or no multivariate adjustment, a focus on single risk factors studied in isolation, overlapping cohorts, survivorship effects, and small sample sizes. These limitations raise concerns for bias and unmeasured confounding.73, 81-83 Moreover, longitudinal studies are critically few in number; rarer still are those following subjects from before transplant to beyond the first post-transplant year.5, 53 Notably, no U.S. study of HRQL has been reported since 2005 overhaul of the system of U.S. organ allocation (Lung Allocation Score [LAS]),84 which increased the medical acuity of waitlisted patients.85 Therefore, prior studies of HRQL may no longer be generalizable to U.S. populations. Furthermore, studies have yet to measure psychosocial and physiologic factors concurrently before and after transplant. The knowledge gaps of the cumulative and relative effect of these factors on HRQL hinder the development of interventions designed to relieve disability and further improve HRQL.

Additionally, a thematic imbalance across these studies identifies areas ripe for future research. The majority of studies focused on individual determinants of HRQL. Studies of interventions and instrument validation/methodology were infrequently represented. Moreover, the heterogeneity of HRQL instruments employed further magnifies the underlying imbalance. Many instruments were not respiratory-specific and none were specific to LT. While this heterogeneity makes cross-study comparisons difficult, these data lay the groundwork for the development of a LT-specific instrument. Finally, we identified only one study that employed qualitative methods. This represents a significant shortcoming as qualitative methods are generally considered a prerequisite for adequate characterization of disease-specific HRQL constructs.

Future Directions

The limitations discussed above provide a roadmap to advance HRQL in LT. Existing limitations and gaps aligned with potential research solutions are summarized in Table 3. In particular, the path forward includes longitudinal studies (accounting for survivorship and important covariates) and investigations in understudied thematic areas. Future studies should use structured instruments (established or newly developed, all with appropriate validation for LT populations) as well as qualitative approaches. Additionally, since immunosuppressives used in LT have broad effects, studies should consider use of both respiratory-specific and generic instruments. Indeed, in HRQL assessment, respiratory-specific and generic measures are considered complementary rather than duplicative. Not only do generic instruments capture transplant-related co-morbidities and treatment side-effects, they also permit comparisons of HRQL across other types of solid-organ transplantation. On the other hand, respiratory-specific instruments are likely to be more sensitive in measuring the impact of respiratory factors such as BOS.75

Table III.

Existing Research Limitations and Future Directions

| Existing Research Limitations and Gaps | Future Directions |

|---|---|

| Lack of instruments validated for use in lung transplant population. The wide variety of instruments employed in the existing literature limits interpretability and pooling of results. | •The research agenda should emphasize the need for studies that examine the performance characteristics of HRQL instruments in lung transplant populations (e.g., reliability, validity, responsiveness). •Qualitative studies are needed. These studies are considered a prerequisite for adequate characterization of disease-specific HRQL constructs (i.e., content validity). •The pulmonary transplant community with professional society engagement should develop a shared understanding of how HRQL should be conceptually defined. This definition may identify existing instruments for use or highlight the need for a novel instrument in lung transplant to be developed. •Studies should include both generic and respiratory-specific HRQL instruments to maximize responsiveness to changes in allograft status and capture systemic effects of transplant-related co-morbidities and treatment side effects. |

| Methodological limitations including: | To address these limitations, studies should: |

| •Incomplete or no multivariate adjustment •Selection bias (e.g., studies enrolled only those subjects healthy enough to attend clinic or those who chose to return mailed questionnaires) •Survivorship (e.g., subjects who died did not contribute HRQL data resulting in potentially inflated effect estimates) •Overlapping cohorts •Small sample sizes • Scant HRQL data beyond the first post-operative year •No published U.S. data since the Lung Allocation Score was instituted. Existing effect estimates may not be generalizable to contemporary U.S. populations. |

•Account for known and/or potentially important covariates and employ multivariate analysis • Employ strategies such as telephone surveys, repeated efforts to contact subjects who don't respond to initial attempts, and/or home visits to minimize selection bias •Account for deaths explicitly through strategies such as “extreme case analysis”, “carry forward” or multiple imputation. •Greater transparency regarding overlapping subject data between studies. • Perform power calculations a priori to inform sample size selection • Address small sample sizes through multi-center studies or incorporating HRQL measures into existing registries once common metrics have been defined. •Extend HRQL assessments beyond the first post-operative year; key timepoints should be targeted (such as years 3 and 5) that parallel existing clinical benchmarks. •Evaluate contemporary U.S. subjects and across the spectrum of transplant urgency (LAS) |

| Lack of longitudinal studies and long-term follow up | Studies of HRQL over time should employ true longitudinal designs with repeated measures of the same subjects over time. |

Central to advancing the field is developing a shared understanding within the pulmonary transplant community of how HRQL in LT should be conceptually defined. Consensus definitions of primary graft dysfunction and bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome, for example, have led to important scientific progress. Such definitions, with professional society engagement, could direct research efforts by defining relevant domains of HRQL and identifying instruments that best assess them in LT. If existing instruments fail to meet the criteria identified, this would serve to underscore prioritization for funding necessary to develop novel instruments specific to LT. Consensus definitions could also guide instrument selection for future investigators, thereby reducing cross-study heterogeneity. Once common metrics are established, HRQL instruments could potentially be incorporated into existing LT registries. Such incorporation could address sample size limitations and aid efforts to understand the impact of lung transplant on HRQL, identify areas for intervention, and even inform organ allocation.

Despite advances in our understanding of HRQL in the field of LT, many important questions remain. The next decade promises additional understanding as we address these questions armed with new research methods and tools among a growing cohort of international researchers focused on this area of inquiry. This understanding is critically important for providing patients with evidence-based counseling, identifying areas for interventions aimed at maximizing the HRQL benefit from transplant, exploring efforts to incorporate patient-centered outcomes into clinical decision-making, and more broadly quantifying the “net”-benefit afforded by lung transplantation.

Table II.

Instruments and measures employed in studies

| Category | Instrument or measure | Studies | N study sites | N patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRQL | ||||

| Generic | • Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form-36‡ | Archonti 2004; Beilby 2003; Cohen 1998; De Vito Dabbs 2009; Eskander2011; Feurer 2004; Girard 2006; Goetzmann 2008; Hummel 2001; Ihle 2011; Kollner 2002; Kugler 2004; Kugler 2010; Langer 2009; Lobo 2004; Limbos 1997; Limbos 2000; Littlefield 1996; Lutogniewska 2010; Ortega 2009; Pinson 2000; Munro 2009; MacNaughton 1998; Nilsson 2011; Ricotti 2006; Rodrigue 2005; Rodrigue 2006; Rutherford 2005; Smeritschnig 2005; Stavern 2000; Vasiliadis 2006 |

23 | 1913† |

| • Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form-20 | Gross 1995 | 1 | 98 | |

| • Medical Outcomes Survey Short Form-12 | Kunsebeck 2007 | 1 | 119 | |

| • Nottingham Health Profile | Busschbach 1994; Caine 1991; O'Brien 1988; TenVergert 1998; TenVergert 2001; Van Den 2000; Vermeulen 2003; Vermeulen 200432; Vermeulen 200428; Vermeulen 2005; Vermeulen 2007; Vermeulen 2008 |

4 | 1078† | |

| • Quality of Well Being Scale | Squier 1995; Stilley 1999 | 2 | 110 | |

| • Quality of Life Profile for Chronic Diseases | Ihle 2011; Kugler 2004; Kugler 2005; Kugler 2007; Tegtbur 2004 |

2 | 715† | |

| • FLZM Questions on Life Satisfaction (Health Satisfaction Module) | Irani 2006 | 1 | 89 | |

| Disease-specific: Respiratory | • St George's Respiratory Questionnaire‡ | Eskander 2011; Gerbase 2005; Gerbase 2008; Ihle 2011; Kugler 2004; Lutogniewska 2010; Ricotti 2006; Smeritschnig 2005; Stavern 2000 |

8 | 704† |

| • Seattle Obstructive Lung Disease Questionnaire | Silvertooth 2004 | 1 | 27 | |

| • Chronic Respiratory Questionnair (CRQ) | Vivodtzev 2011 | 1 | 12 | |

| Disease-specific: Gastrointe stinal | • Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index | Robertson 2011 | 1 | 16 |

| Health status | • Sickness Impact Profile | De Vito Dabbs 2003; De Vito Dabbs 2009; Lanuza 2000; Ramsey 1995; Stilley 1999 |

3 | 178† |

| Health Utilities | • Euroqol 5D | Anyanwu 2001; Busschbach 1994 (only Euroqol VAS); Eskander 2011; Santana 201051; Santana 201061 |

4 | 886† |

| • Standard Gamble‡ | Busschbach 1994; Eskander 2011; Ramsey 1995; Singer 2005; Vasiliadis 2005 |

5 | 365 | |

| • Time trade-off (derived from Standard Gamble) | Busschbach 1994 | 1 | 6 | |

| • Health Utilities Index 2 and 3‡ | Santana 2009; Santana 201051; Santana 201061 | 1 | 469† | |

| • Index of Well Being (also a HRQL instrument) | Gross 1995; TenVergert 1998; TenVergert 2001; van den Berg 2000; Vermeulen 2003; Vermeulen 200428; Vermeulen 200432; Vermeulen 2008 |

2 | 689 | |

| • Visual Analog Scale | Eskander 2011; Gerbase 2005; Gerbase 2008; Limbos 2000; Lobo 2004; Matthees 2001; Ricotti 2006; Shih 2002 |

5 | 559† | |

| Quality of Life (not solely health-related) | • Quality of Life Index | Kurz 2001 | 1 | 25 |

| • FLZM Questions on Life Satisfaction (General Life Satisfaction Module) | Irani 2006 | 1 | 89 | |

| Psychological | ||||

| Depression and Anxiety | • Spielberger's State Trait Anxiety Inventory | Cohen 1998; Girard 2006; Littlefield 1996; TenVergert 1998; TenVergert 2001; Van Den 2000; Vermeulen 2003; Vermeulen 200432; Vermeulen 200428; Vermeulen 2005; Vermeulen 2007; Vermeulen 2008 |

3 | 1156† |

| • Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale‡ | Irani 2006; Irani 2010; Limbos 1997; Limbos 2000 Rutherford 2005; Santana 2009; Santana 201061; Santana 201051; Smeritschnig 2005; Stavern 2000 |

6 | 982† | |

| • Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale | TenVergert 1998; TenVergert 2001; van den Berg 2000; Vermeulen 2003; Vermeulen 200428; Vermeulen 200432; Vermeulen 2007; Vermeulen 2008 |

1 | 731† | |

| • Beck Depression Inventory (BDI or BDI-II) | Archonti 2004; Girard 2006; Kunsebeck 2007; Silvertooth 2004; Squier 1995 |

5 | 355 | |

| • Center of Epidemiologic Studies- Depression Scale | Lobo 2004; Matthees 2001; Kunsebeck 2007 |

2 | 317† | |

| • Hamilton Depression Rating Scale | Silvertooth 2004 | 1 | 27 | |

| • Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale | Silvertooth 2004 | 1 | 27 | |

| • Mental Health Inventory | Cohen 1998; Littlefield 1996 | 1 | 119† | |

| Sense of Mastery | • Sense of Mastery Scale | De Vito Dabbs 2003; Stilley 1999 | 1 | 86† |

| Coping | • Brief COPE Scale (28-item) | Myaskovsky 2006 | 1 | 199† |

| • Coping Checklist | De Vito Dabbs 2003 | 1 | 50 | |

| • Coping with everyday life | Kunsebeck 2007 | 1 | 119 | |

| Self-esteem | • Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (10-items) | Limbos 1997; Limbos 2000; Stilley 1999 | 2 | 186† |

| Life satisfaction | • Summarized Life Satisfaction | Irani 2006 | 1 | 89 |

| • Global life satisfaction | Kugler 2010 | 1 | 88 | |

| Social support | • F-SozU | Archonti 2004; Irani 2006 | 2 | 128 |

| • Caregiver support assessment on caregiver social support (modeled on Spanier1, Pearlin and Schooler2) | Myaskovsky 2006; Stilley 1999 | 1 | 235† | |

| • UCLA Loneliness Scale-Revised | Littlefield 1996 | 1 | 59 | |

| Multidimen sional | • Brief Symptoms Inventory | Limbos 2000; Lanuza 2000 | 2 | 119 |

| • Symptom Checklist-90-Revised | De Vito Dabbs 2003; De Vito Dabbs 2009; Stilley 1999 | 1 | 116† | |

| Friend Support | • Friend support assessment | Myaskovsky 2006 | 1 | 199 |

| Optimism/Pessimism | • Life Orientation Test | Irani 2006; Myaskovsky 2006 | 2 | 288† |

| Adjustment to illness | • Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale‡ | Feurer 2004; Pinson 2000 | 1 | 130† |

| Perceived control | • Perception of Self-Care Agency scale | De Vito Dabbs 2009 | 1 | 30 |

| Desire for control | • Desire for Control Scale | Kurz 2001 | 1 | 25 |

| • Multidimensional Health Locus of Control scales | Cohen 1998 | 1 | 60 | |

| Perceived impact of illness | • Illness Intrusion Rating Scale | Littlefield 1996; Lobo 2004; Matthees 2001 | 2 | 257† |

| Family unit based approach to problem solving | • Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scale | Kurz 2001 | 1 | 25 |

| Body Image | • Body Cathexis Scale | Limbos 1997; Limbos 2000 | 1 | 150† |

| Psychiatric | • Renard Diagnostic Interview Form | De Vito Dabbs 2003; Stilley 1999 | 1 | 86† |

| • General Health Questionnaire | Ricotti 2006 | 1 | 129 | |

| • Impact of Event Scale | Kollner 2002 | 1 | 10 | |

| • Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R | De Vito Dabbs 2003; Kollner 2002 | 2 | 60 | |

| Transplant Specific | • General Health/QOL Rating Scale | Lanuza 2000 | 1 | 10 |

| • Hannover Transplantation Rating Scale | Kunsebeck 2007 | 1 | 119 | |

| • Transplant Effects Questionnaire | Goetzmann 2008 | 1 | 76 | |

| • Perceived threat of the risk for graft rejection (PTGR) | Nilsson 2011 | 1 | 29 | |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Dyspnea | • Baseline Dyspnea Index | Lutogniewska 2010 | 1 | 86 |

| • Borg Scale | Lutogniewska 2010; Ricotti 2006; Vivodtzev 2011 | 3 | 227 | |

| • Dyspnea Scale | Lobo 2004 | 1 | 99 | |

| • Medical Research Council Breathlessness Scale | Lutogniewska 2010 | 1 | 86 | |

| • Oxygen Cost Diagram | Lutogniewska 2010; Stavern 2000 | 2 | 132 | |

| • BOS Score | Rutherford 2005 | 1 | 28 | |

| • Pulmonary Scale (4 items from Symptom Distress scale as well as the Dyspnea scale from the Epidemiology Standardization Project) | Lobo 2004 | 1 | 99 | |

| • | ||||

| Pain | • Brief Pain Inventory | Girard 2006 | 1 | 96 |

| Gastro-esophagea l reflux disease (GERD) | • DeMeester Reflux Questionnaire | Robertson 2011 | 1 | 16 |

| • Reflux Symptom Index (RSI) | Robertson 2011 | 1 | 16 | |

| Multidimensional | • Zerssen Symptom Checklist | Kunsebeck 2007 | 1 | 119 |

| • Cardiac symptom inventory (developed at the Toronto Hospital) | Cohen 1998 | 1 | 60 | |

| Transplant Specific | • Symptom Frequency and Distress Scale | Matthees 2001; Kugler 2007; Lobo 2004; MacNaughton 1998 |

3 | 502† |

| • Simmons’ Post-transplant Symptom Inventory | De Vito Dabbs 2003 | 1 | 50 | |

| Functioning | ||||

| General | • Karnofsky Functional Performance Index | Busschbach 1994; Feurer 2004; Gross 1995; Matthees 2001; Pinson 2000; TenVergert 1998; TenVergert 2001; Vermeulen 2003; Vermeulen 200432; Vermeulen 2008 |

5 | 637† |

| • Activities of daily living (ADLs) | TenVergert 1998 | 1 | 24 | |

| • Sleep disturbance (7-item scale) | Littlefield 1996 | 1 | 59 | |

| Sexual | • Derogatis Sexual Functioning Inventory | Limbos 1997; Limbos 2000 | 1 | 150† |

| • Designed for individual study | Smeritschnig 2005 | 1 | 108 | |

| Qualitative | • Semi-structured interview | Festle 2002 | 1 | 30 |

| Other | ||||

| Medication Adherence | • Medication Adherence Questionnaire | Santana 2009; Santana 201051 | 1 | 256† |

| • Medication Taking Scale | Matthees 2001 | 1 | 99 | |

| • 8-area measure of difficulties with adherence | Littlefield 1996 | 1 | ||

| Work | • Work performance index | Kugler 2010 | 1 | 88 |

| • Employment Status Index | Kugler 2010 | 1 | 88 | |

| Olfactory performance | • Olfactory test battery | Irani 2010 | 1 | 92 |

| Health Habits | • Health Habits Assessment | De Vito Dabbs 2009 | 1 | 30 |

| Exercise | • Leisure Time Exercise Questionnaire | Santana 2009; Santana 201051 | 1 | 256 |

| Religiosity | • 3 items adapted from King and Hunt3 | Myaskofsky 2006 | 1 | 199 |

| Opinion of healthcare provider | • Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers | Santana 201051 | 1 | 213 |

| Interview-based | • Semi-structured interview | Kugler 2004 (based on the Illness Belief Model); Shih 2002 | 2 | 69 |

| Specific to individual study | • Satisfaction with transplant outcome, adverse effects of immunosuppression | Smeritschnig 2003 | 1 | 108 |

| • Complementary and alternative medicine | Matthees 2001 | 1 | 99 | |

| • Two open-ended questions concerning women | Limbos 1997 | 1 | 41 |

Study subject counts do not account for the potential of overlapping cohorts within the contributing studies.

Instrument validated in LT populations. Validated instruments include: SF-36, SGRQ, SG, HUl-Mark 3, HADS and PAIS.

Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: new scale assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and Family, Vol. 38, No. 1 (Feb., 1976), pp. 15-28.

Pearlin L, Schooler C. The structure of coping. J Health Soc Behav. March 1978; 19: 2-21.

King M, Hunt R. Measuring the religious variable: National replication. J Sci Study Religion 1975; 14: 13.

Acknowledgements

Grant support: Supported in part by NHLBI K23 HL111115, F32 HL107003-01 (J.S.), NHLBI K23 HL086585 (H.C.), and Novartis Pharmaceuticals (J.S.,P.B.)

ABBREVIATIONS

- HRQL

Health-related quality of life

- LT

lung transplantation

- PCOs

patient-centered outcomes

- BOS

bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome

- SGRQ

St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire

- NHP

Nottingham Health Profile

- EQ-5D

5-Dimensional EuroQOL

- SF-36

36-item Short Form Health Survey

- SF-12

12-item Short Form Health Survey

- HUI measure

Health Utilities Index

- RCT

randomized designs

- LAS

Lung Allocation Score

Footnotes

The majority of the work on this manuscript was completed while Dr. Chen was a member of the UC San Francisco Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, Allergy and Sleep Medicine and the Cardiovascular Research Institute at UC San Francisco.

Disclosure:

JPS and PDB have conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation. They hold an investigator initiated research agreement with Novartis Pharmaceuticals to study health-related quality of life in lung transplantation. No representative from Novartis was involved in any aspect of this manuscript.

The remaining authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Busschbach JJ, Horikx PE, van den Bosch JM, Brutel de la Riviere A, de Charro FT. Measuring the quality of life before and after bilateral lung transplantation in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 1994;105:911–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.3.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eskander A, Waddell TK, Faughnan ME, Chowdhury N, Singer LG. BODE index and quality of life in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease before and after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Limbos MM, Chan CK, Kesten S. Quality of life in female lung transplant candidates and recipients. Chest. 1997;112:1165–74. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.5.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramsey SD, Patrick DL, Lewis S, Albert RK, Raghu G. Improvement in quality of life after lung transplantation: a preliminary study. The University of Washington Medical Center Lung Transplant Study Group. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1995;14:870–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.TenVergert EM, Vermeulen KM, Geertsma A, et al. Quality of life before and after lung transplantation in patients with emphysema versus other indications. Psychol Rep. 2001;89:707–17. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.89.3.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen L, Littlefield C, Kelly P, Maurer J, Abbey S. Predictors of quality of life and adjustment after lung transplantation. Chest. 1998;113:633–44. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.3.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerbase MW, Spiliopoulos A, Rochat T, Archinard M, Nicod LP. Health-related quality of life following single or bilateral lung transplantation: a 7-year comparison to functional outcome. Chest. 2005;128:1371–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.3.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanuza DM, Lefaiver CA, Farcas GA. Research on the quality of life of lung transplant candidates and recipients: an integrative review. Heart Lung. 2000;29:180–95. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2000.105691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacNaughton KL, Rodrigue JR, Cicale M, Staples EM. Health-related quality of life and symptom frequency before and after lung transplantation. Clin Transplant. 1998;12:320–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rodrigue JR, Baz MA, Kanasky WF, Jr., MacNaughton KL. Does lung transplantation improve health-related quality of life? The University of Florida experience. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:755–63. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stavem K, Bjortuft O, Lund MB, Kongshaug K, Geiran O, Boe J. Health-related quality of life in lung transplant candidates and recipients. Respiration. 2000;67:159–65. doi: 10.1159/000029480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kugler C, Fischer S, Gottlieb J, et al. Health-related quality of life in two hundred-eighty lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:2262–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Littlefield C, Abbey S, Fiducia D, et al. Quality of life following transplantation of the heart, liver, and lungs. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1996;18:36S–47S. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(96)00082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinson CW, Feurer ID, Payne JL, Wise PE, Shockley S, Speroff T. Health-related quality of life after different types of solid organ transplantation. Ann Surg. 2000;232:597–607. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200010000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stilley CS, Dew MA, Stukas AA, et al. Psychological symptom levels and their correlates in lung and heart-lung transplant recipients. Psychosomatics. 1999;40:503–9. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3182(99)71189-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vermeulen KM, TenVergert EM, Verschuuren EAM, Erasmus ME, van der Bij W. Pre-transplant Quality of Life Does Not Predict Survival After Lung Transplantation. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2008;27:623–7. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girard F, Chouinard P, Boudreault D, et al. Prevalence and Impact of Pain on the Quality of Life of Lung Transplant Recipients*. Chest. 2006;130:1535–40. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.5.1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irani S, Thomasius M, Schmid-Mahler C, et al. Olfactory performance before and after lung transplantation: Quantitative assessment and impact on quality of life. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2010;29:265–72. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ricotti S, Vitulo P, Petrucci L, Oggionni T, Klersy C. Determinants of quality of life after lung transplant: an Italian collaborative study. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2006;65:5–12. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2006.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singer LG, Gould MK, Tomlinson G, Theodore J. Determinants of health utility in lung and heart-lung transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:103–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasiliadis HM, Collet JP, Poirier C. Health-related quality-of-life determinants in lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:226–33. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vermeulen KM, van der Bij W, Erasmus ME, TenVergert EM. Long-term Health-related Quality of Life After Lung Transplantation: Different Predictors for Different Dimensions. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2007;26:188–93. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerbase MW, Soccal PM, Spiliopoulos A, Nicod LP, Rochat T. Long-term health-related quality of life and walking capacity of lung recipients with and without bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27:898–904. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunsebeck HW, Kugler C, Fischer S, et al. Quality of life and bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome in patients after lung transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2007;17:136–41. doi: 10.1177/152692480701700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smeritschnig B, Jaksch P, Kocher A, et al. Quality of life after lung transplantation: a cross-sectional study. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:474–80. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2003.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van den Berg J, Geertsma A, van Der BW, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation and health-related quality of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1937–41. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.6.9909092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vermeulen KM, Groen H, van der Bij W, Erasmus ME, Koeter GH, TenVergert EM. The effect of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome on health related quality of life. Clin Transplant. 2004;18:377–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2004.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anyanwu AC, McGuire A, Rogers CA, Murday AJ. Assessment of quality of life in lung transplantation using a simple generic tool. Thorax. 2001;56:218–22. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ortega T, Deulofeu R, Salamero P, et al. Health-related Quality of Life before and after a solid organ transplantation (kidney, liver, and lung) of four Catalonia hospitals. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:2265–7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singer LG, Chowdhury N, Chaparro C, Hutcheon MA. 175: Post-Lung Transplant Health-Related Quality of Life: Perception and Reality. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2009;28:S127–S. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vermeulen KM, van der Bij W, Erasmus ME, Duiverman EJ, Koeter GH, TenVergert EM. Improved quality of life after lung transplantation in individuals with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37:419–26. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kugler C, Fischer S, Gottlieb J, et al. Symptom experience after lung transplantation: impact on quality of life and adherence. Clinical Transplantation. 2007;21:590–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2007.00693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lutogniewska W, Jastrzebski D, Wyrwol J, et al. Dyspnea and quality of life in patients referred for lung transplantation. Eur J Med Res. 2010;15(Suppl 2):76–8. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-15-S2-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wildgaard K, Iversen M, Kehlet H. Chronic pain after lung transplantation: a nationwide study. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:217–22. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b705e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tegtbur U, Sievers C, Busse MW, et al. [Quality of life and exercise capacity in lung transplant recipients]. Pneumologie. 2004;58:72–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-812526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Archonti C, D'Amelio R, Klein T, Schafers HJ, Sybrecht GW, Wilkens H. [Physical quality of life and social support in patients on the waiting list and after a lung transplantation]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 2004;54:17–22. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-812589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Limbos MM, Joyce DP, Chan CK, Kesten S. Psychological functioning and quality of life in lung transplant candidates and recipients. Chest. 2000;118:408–16. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.2.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santana MJ, Feeny D, Jackson K, Weinkauf J, Lien D. Improvement in health-related quality of life after lung transplantation. Can Respir J. 2009;16:153–8. doi: 10.1155/2009/843215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Festle MJ. Qualifying the quantifying: assessing the quality of life of lung transplant recipients. Oral Hist Rev. 2002;29:59–86. doi: 10.1525/ohr.2002.29.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feurer ID, Moore DE, Speroff T, et al. Refining a health-related quality of life assessment strategy for solid organ transplant patients. Clin Transplant. 2004;18(Suppl 12):39–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2004.00216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goetzmann L, Sarac N, Ambuhl P, et al. Psychological response and quality of life after transplantation: a comparison between heart, lung, liver and kidney recipients. Swiss Med Wkly. 2008;138:477–83. doi: 10.4414/smw.2008.12160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Irani S, Mahler C, Goetzmann L, Russi EW, Boehler A. Lung transplant recipients holding companion animals: impact on physical health and quality of life. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:404–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kollner V, Schade I, Maulhardt T, Maercker A, Joraschky P, Gulielmos V. Posttraumatic stress disorder and quality of life after heart or lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:2192–3. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurz JM. Desire for control, coping, and quality of life in heart and lung transplant candidates, recipients, and spouses: a pilot study. Prog Transplant. 2001;11:224–30. doi: 10.1177/152692480101100313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Myaskovsky L, Dew MA, McNulty ML, et al. Trajectories of Change in Quality of Life in 12-Month Survivors of Lung or Heart Transplant. American Journal of Transplantation. 2006;6:1939–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Myaskovsky L, Dew MA, Switzer GE, et al. Avoidant coping with health problems is related to poorer quality of life among lung transplant candidates. Prog Transplant. 2003;13:183–92. doi: 10.1177/152692480301300304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nilsson M, Forsberg A, Backman L, Lennerling A, Persson LO. The perceived threat of the risk for graft rejection and health-related quality of life among organ transplant recipients. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:274–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.De Vito Dabbs A, Dew MA, Stilley CS, et al. Psychosocial vulnerability, physical symptoms and physical impairment after lung and heart-lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22:1268–75. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(02)01227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beilby S, Moss-Morris R, Painter L. Quality of life before and after heart, lung and liver transplantation. N Z Med J. 2003;116:U381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santana M-J, Feeny D, Johnson J, et al. Assessing the use of health-related quality of life measures in the routine clinical care of lung-transplant patients. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19:371–9. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9599-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kugler C, Strueber M, Tegtbur U, Niedermeyer J, Haverich A. Quality of life 1 year after lung transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2004;14:331–6. doi: 10.1177/152692480401400408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kugler C, Tegtbur U, Gottlieb J, et al. Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors after heart and lung transplantation: a prospective cohort study. Transplantation. 2010;90:451–7. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181e72863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodrigue JR, Baz MA, Kanasky JWF, MacNaughton KL. Does Lung Transplantation Improve Health-Related Quality of Life? The University of Florida Experience. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2005;24:755–63. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vermeulen KM, Ouwens JP, van der Bij W, de Boer WJ, Koeter GH, TenVergert EM. Long-term quality of life in patients surviving at least 55 months after lung transplantation. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003;25:95–102. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(03)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Eskander A, Waddell TK, Faughnan ME, Chowdhury N, Singer LG. BODE index and quality of life in advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease before and after lung transplantation. The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2011;30:1334–41. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O'Brien BJ, Banner NR, Gibson S, Yacoub MH. The Nottingham Health Profile as a measure of quality of life following combined heart and lung transplantation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1988;42:232–4. doi: 10.1136/jech.42.3.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.TenVergert EM, Essink-Bot ML, Geertsma A, van Enckevort PJ, de Boer WJ, van der Bij W. The effect of lung transplantation on health-related quality of life: a longitudinal study. Chest. 1998;113:358–64. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.2.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodrigue JR, Baz MA. Are there sex differences in health-related quality of life after lung transplantation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:120–5. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Caine N, Sharples LD, Smyth R, et al. Survival and quality of life of cystic fibrosis patients before and after heart-lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:1203–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Santana MJ, Feeny D, Ghosh S, et al. The construct validity of the health utilities index mark 3 in assessing health status in lung transplantation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2010;8:110. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vasiliadis HM, Collet JP, Penrod JR, Ferraro P, Poirier C. A cost-effectiveness and cost-utility study of lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:1275–83. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gross CR, Savik K, Bolman RM, 3rd, Hertz MI. Long-term health status and quality of life outcomes of lung transplant recipients. Chest. 1995;108:1587–93. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.6.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lobo FS, Gross CR, Matthees BJ. Estimation and comparison of derived preference scores from the SF-36 in lung transplant patients. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:377–88. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018488.95206.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matthees BJ, Anantachoti P, Kreitzer MJ, Savik K, Hertz MI, Gross CR. Use of complementary therapies, adherence, and quality of life in lung transplant recipients. Heart Lung. 2001;30:258–68. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2001.116135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shih FJ, Tsao CI, Lin MH, Lin HY. The context framing the changes in health-related quality of life and working competence before and after lung transplantation: one-year follow-up in Taiwan. Transplant Proc. 2002;34:2801–6. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(02)03481-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ihle F, Neurohr C, Huppmann P, et al. Effect of inpatient rehabilitation on quality of life and exercise capacity in long-term lung transplant survivors: a prospective, randomized study. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2011;30:912–9. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lanuza DM, Lefaiver C, Mc Cabe M, Farcas GA, Garrity E., Jr Prospective study of functional status and quality of life before and after lung transplantation. Chest. 2000;118:115–22. doi: 10.1378/chest.118.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hummel M, Michauk I, Hetzer R, Fuhrmann B. Quality of life after heart and heart-lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:3546–8. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02427-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Langer D, Gosselink R, Pitta F, et al. Physical activity in daily life 1 year after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:572–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rutherford RM, Fisher AJ, Hilton C, et al. Functional status and quality of life in patients surviving 10 years after lung transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:1099–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Munro PE, Holland AE, Bailey M, Button BM, Snell GI. Pulmonary rehabilitation following lung transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:292–5. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vermeulen KM, Post WJ, Span MM, van der Bij W, Koeter GH, TenVergert EM. Incomplete quality of life data in lung transplant research: comparing cross sectional, repeated measures ANOVA, and multi-level analysis. Respir Res. 2005;6:101. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.DeVito Dabbs A, Dew MA, Myers B, et al. Evaluation of a hand-held, computer-based intervention to promote early self-care behaviors after lung transplant. Clin Transplant. 2009;23:537–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.00992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vivodtzev I, Pison C, Guerrero K, et al. Benefits of home-based endurance training in lung transplant recipients. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;177:189–98. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Silvertooth EJ, Doraiswamy PM, Clary GL, et al. Citalopram and quality of life in lung transplant recipients. Psychosomatics. 2004;45:271–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Singer LG, Theodore J, Gould MK. Validity of standard gamble utilities as measured by transplant readiness in lung transplant candidates. Med Decis Making. 2003;23:435–40. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03258421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Squier HC, Ries AL, Kaplan RM, et al. Quality of well-being predicts survival in lung transplantation candidates. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:2032–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Benzo R, Farrell MH, Chang CC, et al. Integrating health status and survival data: the palliative effect of lung volume reduction surgery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:239–46. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200809-1383OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McDowell I. Measuring Health: A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yusen RD. Lung transplantation outcomes: the importance and inadequacies of assessing survival. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1493–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yusen RD. Technology and outcomes assessment in lung transplantation. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:128–36. doi: 10.1513/pats.200809-102GO. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yusen RD. Survival and quality of life of patients undergoing lung transplant. Clin Chest Med. 2011;32:253–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Egan TM, Murray S, Bustami RT, et al. Development of the new lung allocation system in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1212–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yusen RD, Shearon TH, Qian Y, et al. Lung transplantation in the United States, 1999-2008. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1047–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]