Abstract

Bone mineral density (BMD) is a strong predictor of fracture, yet most fractures occur in women without osteoporosis by BMD criteria. To improve fracture-risk prediction, the World Health Organization recently developed a country-specific fracture risk index of clinical risk factors (FRAX®) that estimates 10-year probabilities of hip and major osteoporotic fracture. Within differing baseline BMD categories, we evaluated 6252 women age 65 and older in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures using FRAX 10-year probabilities of hip and major osteoporotic fracture (hip, clinical spine, wrist, humerus) compared to incidence of fractures over 10 years of follow-up. Overall ability of FRAX to predict fracture risk based on initial BMD T-score categories (normal, low bone mass, and osteoporosis) was evaluated with receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) analyses using area-under-the-curve (AUC). Over 10 years of follow-up, 368 women incurred a hip fracture, and 1011 a major osteoporotic fracture. Women with low bone mass represented the majority (n=3791; 61%); they developed many hip (n=176; 48%) and major osteoporotic fractures (n=569; 56%). Among women with normal and low bone mass, FRAX (including BMD) was an overall better predictor of hip fracture risk (AUC = 0.78 and 0.70, respectively) than major osteoporotic fractures (AUC = 0.64 and 0.62). Simpler models (e.g., age+prior fracture) had similar AUCs to FRAX, including among women for whom primary prevention is sought (no prior fracture or osteoporosis by BMD). The FRAX, and simpler models, predict 10-year risk of incident hip and major osteoporotic fractures in older U.S. women with normal or low bone mass.

Keywords: osteopenia, osteoporosis, fracture, risk, prediction

INTRODUCTION

Although bone mineral density (BMD) is a strong predictor of fracture risk,(1,2) only a small portion of women meet BMD criteria for osteoporosis, and thus the majority of fractures occur in women with low bone mass (previously called osteopenia).(3) To improve fracture prediction, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recently developed a country-specific fracture risk index using nine clinical risk factors in addition to BMD.(4–6) The U.S. National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) subsequently released guidelines recommending treatment for women with existing hip or spine fracture, osteoporosis by BMD (T-score ≤ −2.5), or low bone mass by BMD (−2.5 < T <−1.0) with an increased risk of fracture based on the FRAX model.(7) FRAX appears similar to age-adjusted BMD alone in overall prediction of fracture risk in postmenopausal women.(8) However, it is unknown how well the FRAX model predicts fractures across differing levels of BMD, particularly among women with low bone mass—who present the greatest treatment dilemma. The aim of our study was to evaluate how the FRAX model 10-year probabilities predicted actual fractures observed over 10 years in a prospective U.S. cohort of women age 65 and older.

METHODS

Study Sample

In 1986–88, the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) recruited 9704 community-dwelling women, who were age 65 or older (>99% Non-Hispanic White) in four U.S. regions: Baltimore County, Maryland; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Portland, Oregon; and the Monongahela Valley near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.(1) Women were recruited irrespective of BMD and fracture history; those unable to walk without assistance and those with bilateral hip replacements were excluded. All women provided written consent, and SOF was approved by each site’s Institutional Review Board.

About two years after the initial visit, 9339 (of 9451 surviving) SOF women returned for a visit that included their first DXA BMD measurement in the clinic; 7963 had adequate DXA BMD measurement. For this analysis we required women to have measurements for all of the risk factors at the baseline in the FRAX model, as well as femoral neck BMD. Among the 7963 women with BMD, the primary reason for missing FRAX risk factors was unknown parental history of fracture (n=1445). Complete data to calculate FRAX data was available on 6252 women. Women who were missing risk factors for FRAX were on average older (72.3 vs. 71.3) and a larger proportion reported a previous history of fracture (42% vs 34%). However, the 6252 women in the analytic cohort and those missing FRAX risk factors had similar BMI (26.4 kg/m2) and similar femoral neck BMD (0.65 g/cm2).

Measurement of Clinical Risk Factors, Including BMD

Measurement and quality control procedures were rigorous (detailed elsewhere).(1) At the baseline examination (1986–8), height was measured by stadiometer, and weight (in light clothing without shoes) by balance-beam scale. Women also provided information on date of birth, personal fracture history after age 50, parental history of hip fracture, smoking status, alcohol use, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and glucocorticoid use. At the second visit (1988–90), dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) was first available, and measured by Hologic QDR 1000 (Hologic, Bedford, Massachusetts) at the proximal femur and lumbar spine. DXA BMD measurement standards and precision have also been previously detailed.(9) T-scores were calculated using the National Health and Examination Survey (NHANES) young female age 20–29 as the reference, and were computed by WHO criteria.(10)

Follow-up for Ascertainment of Fractures

Participants were contacted every four months by postcard (with phone follow-up for non-responders) to ascertain incident hip and other non-spine fractures; more than 98% of these contacts were completed. Incident non-spine fractures were physician-adjudicated from radiology reports. Clinical spine fractures were also adjudicated, when reported. Major osteoporotic fractures included: hip, clinical spine, wrist (distal radius or ulna), and humerus.

WHO and FRAX 10-year Absolute Fracture Risk

The WHO 10-year absolute risk of both hip fracture and major osteoporotic fracture (hip, clinical spine, wrist, or humerus) was calculated for each SOF participant by the WHO Collaborating Centre for Metabolic Bone Disease using the FRAX algorithm for U.S. Caucasian women,(6) and provided to SOF (FRAX Version 3.0 was used for final analyses).(11,12) The FRAX 10-year probabilities are based on the following risk factors: age, sex, body mass index (kg/m2), previous history of fracture, parental history of hip fracture, current smoking, glucocorticoid use in the last three months, presence of RA, other types of secondary osteoporosis, and 3 or more alcoholic beverages a day.(6) For secondary osteoporosis, only RA was assessed in SOF. However, the U.S. FRAX model calculator (with BMD) similarly does not consider other types of secondary causes of osteoporosis in the FRAX calculation when BMD is known as they typically mediate their risk through BMD.(7) FRAX 10-year probabilities were provided both with and without femoral neck (FN) BMD. We did not evaluate use of non-hip BMD (e.g., spine), nor is this recommended with the FRAX calculator as it has not been validated.(7)

Statistical Analyses

To compare 10-year FRAX predicted fracture risk to observed fracture risk in our cohort, we evaluated 6252 women who had measurements for all nine risk factors as well as DXA BMD. To allow an adequate comparison with the 10-year FRAX probabilities, we also limited follow-up to 10 years (mean follow-up was 9.4 years, range 2.2 years–10.0 years).

We evaluated each individual woman’s FRAX predicted probability of hip and major osteoporotic fracture compared to observed rates of hip and major osteoporotic fracture, both with and without FN BMD T-score in the FRAX model.(5,6) We did additional analyses that included traumatic fractures as part of observed fractures to confirm results were consistent for all fracture types (data not shown).

As our goal was to evaluate how FRAX predicts fractures across varying levels of baseline BMD, we stratified results based on initial FN BMD T-score by 0.5 increments as well as T-score groups: normal (T ≥ −1.0), low bone mass (−2.5 < T <−1.0); and osteoporotic (T≤ −2.5). So that within strata comparisons (e.g., comparisons within the low bone mass group) to FRAX would be valid, we developed our models on the full population before stratifying by BMD. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves assessed overall sensitivity and specificity to predict observed hip and major osteoporotic fractures by the area under the ROC Curve (AUC) statistic) using the 10-year probabilities of hip and major osteoporotic fractures, respectively, calculated with FRAX.(5,6) Higher AUC values represent better prediction with the models. STATA® version 9.2 was used to compare the AUC statistic across BMD groups (StataCore, College Station, Texas). All other statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We used χ2 tests and analysis of variance to test bivariate associations. A STATA algorithm by DeLong, DeLong, and Clarke-Pearson(13) was used to test the equality of the area under the curve across the three BMD groups. Post-hoc pair-wise comparisons using the same procedure were also conducted. Linear trends in AUC statistics were also tested using regression analyses. Specifically, the AUC statistic was regressed on the BMD group (normal, low bone mass, osteoporotic). For these trend analyses, observations were weighted by the standard deviation of the AUC statistic and BMD groups were assumed to be equally spaced. The p-value (for trend) reported is for the slope of the regression equation.

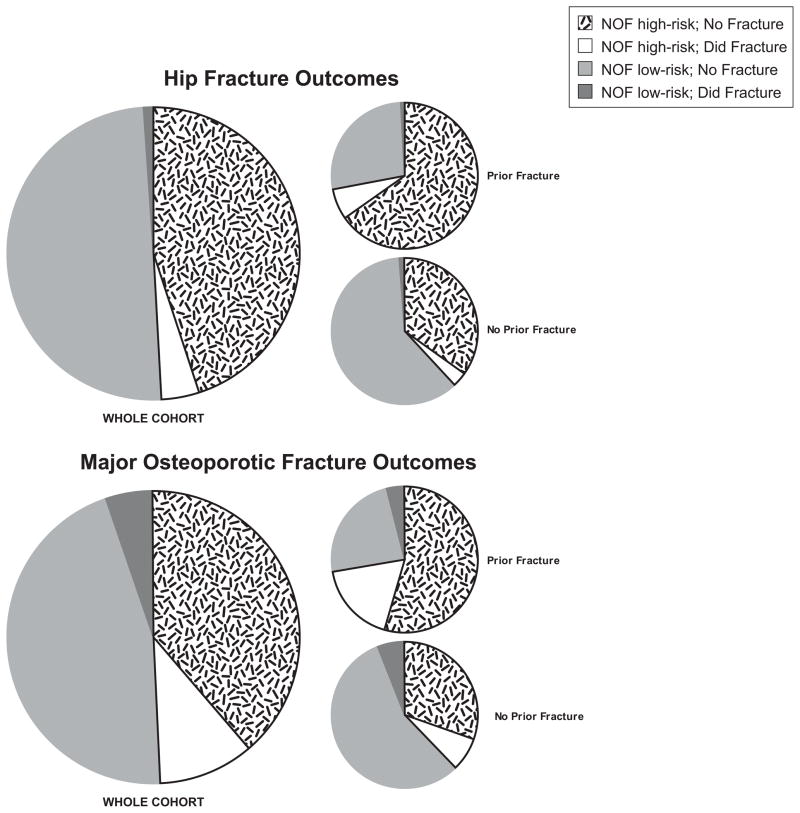

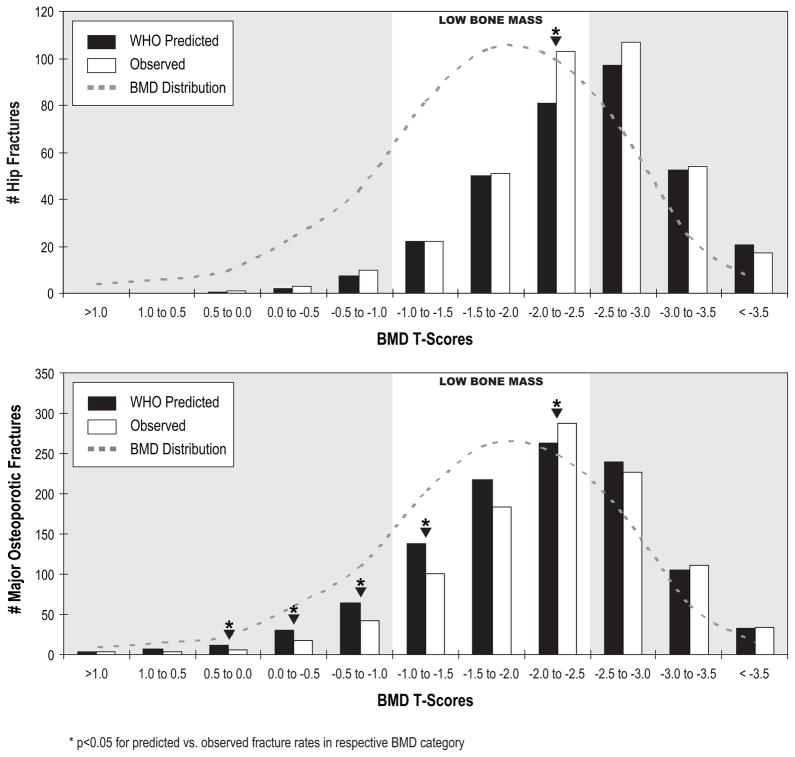

Within each 0.5 T-score increment, we used t-tests to compare the FRAX-predicted probability of fracture to the actual fracture proportions. We summarized these findings in terms of predicted and observed number of fractures within each of the BMD categories by 0.5 T-score increments (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of women with low bone mass (n=4464) at baseline exam that would meet current National Osteoporosis (NOF) treatment thresholds (high-risk; n=2218) or not (low-risk; n=2246), with further stratification on whether fracture occurred in 10 years of follow-up. NOF high-risk is low bone mass (T score between −1.0 and −2.5 by femoral neck or spine BMD) and 10 year FRAX (including BMD) probability of fracture of ≥3% for hip and ≥20% for major osteoporotic fracture (MOF).(7) Proportions are illustrated for the whole cohort (n=4,464), as well as by a prior history of fracture (n=1505) or no prior fracture history (n=2,959).

Although the FRAX model was developed using other data, we confirmed there was no evidence of multi-collinearity between predictor variables used in the FRAX calculations in all comparisons (r<0.4). All the statistical tests that we report are two-sided; the term statistically significant implies a p-value <0.05.

Sensitivity Analyses based on Prior Fracture Status or Age at Baseline

In addition to evaluating overall probabilities in the whole cohort, we did separate analyses among the 4097 (65.5%) women with no prior fracture history (those who did not report any fracture since age 50 at the baseline exam). We also stratified these analyses by age at baseline (≤75 years vs. >75 years).

Sensitivity Analyses of US FRAX Treatment Thresholds

A primary aim of our analysis was to evaluate FRAX among women with low bone mass (“osteopenia”)—those who present a clinical conundrum about treatment benefit. The US NOF recommends pharmacologic treatment of high-risk women with low bone mass (T-score between −1.0 and −2.5 on either femoral neck or lumbar spine) if they have a 10-year probability of a hip fracture ≥3% or a 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture ≥20% based on the US adapted FRAX model.(7) Based on NOF criteria, we dichotomized the 4464 women who had low bone mass (LBM) by femoral neck or spine BMD depending on whether the NOF would recommend treatment (FRAX high risk; n=2218) or not (FRAX low risk; n=2246).(7) We then evaluated what proportion of the high and low risk groups of LBM women developed a fracture over 10 years. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of NOF treatment thresholds for FRAX were also calculated in these LBM women.(14,15)

RESULTS

The characteristics of the 6252 women, who were an average age of 71 years at the baseline exam, are shown in Table 1, stratified by baseline BMD category. All risk factors, except history of RA and corticosteroid use, significantly differed based on baseline BMD T-score (Table 1). Over a total of 58,879 person-years of follow-up, 368 women suffered a hip fracture and 1011 incurred a major osteoporotic fracture. Fracture risk increased with decreasing BMD as would be expected (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the SOF Cohort at Baseline, and Over 10 Years of Follow-up

| Risk Factors Used in FRAX Model: | Normala (n=1154) | Low Bone Massa (n=3791) | Osteoporotica (n=1307) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69.6 (4.0) | 71.1 (4.8) | 73.6 (5.9) | <.001 |

| Sex – Female | 100% | 100% | 100% | — |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 29.0 (5.2) | 26.5 (4.3) | 24.1 (3.6) | <.001 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis – Ever | 67 (5.8) | 258 (6.8) | 104 (8.0) | .11 |

| Steroid Use – Ever | 146 (12.7) | 432 (11.4) | 163 (12.5) | .38 |

| Smoking – Current | 90 (7.8) | 347 (9.2) | 146 (11.2) | .01 |

| Alcohol Use – >=3 Drinks/day | 46 (4.0) | 109 (2.9) | 29 (2.2) | .03 |

| Fracture of Any Bone After Age 50 | 253 (21.9) | 1251 (33.0) | 651 (49.8) | <.001 |

| History of Parental Hip Fracture | 132 (11.4) | 557 (14.7) | 236 (18.1) | <.001 |

| Femoral Neck BMD – T-score | −0.32 (0.66) | −1.79 (0.41) | −2.90 (0.33) | — |

| Other Variables and Outcomes: | ||||

| Femoral Neck BMD, g/cm2 | 0.82 (0.08) | 0.64 (0.05) | 0.51 (0.04) | |

| Total Hip BMD, g/cm2 | 0.93 (0.10) | 0.76 (0.08) | 0.61 (0.08) | |

| Years Follow-up | 9.6 (1.3) | 9.5 (1.4) | 9.1 (1.8) | |

| Hip Fractures - Observed | 14 (1.2) | 176 (4.7) | 178 (14.3) | <.001 |

| Hip Fractures – Predicted b | 11 (0.9) | 153 (4.0) | 170 (13.0) | |

| Major Osteoporotic Fractures - Observed | 71 (6.3) | 569 (15.7) | 371 (30.0) | <.001 |

| Major Osteoporotic Fractures – Predicted c, d | 115 (10.0) | 615 (16.2) | 376 (28.8) | |

Data are presented as mean (SD) or n (%).

Based on initial femoral neck T-score

Using FRAX hip fracture probability with BMD

Using FRAX major osteoporotic fracture probability with BMD

Major osteoporotic fractures include hip, clinical spine, wrist and humerus(6)

A model with no utility in predicting fracture would have an AUC of 0.50 (i.e., no better than flipping a coin or chance alone); AUC was greater than 0.50 for all models (Table 2). The FRAX model predicted hip and major osteoporotic fractures within all BMD categories, even when baseline BMD was not part of the probability calculation (Table 2). However, prediction with FRAX models was similar to simpler models (Table 2). In general, overall prediction was better (higher AUCs) for all hip fracture models (using either FRAX or simpler models) than it was for major osteoporotic fracture.

Table 2.

Prediction of Fracture, Stratified by Baseline BMD

| Normal N=1154 |

Low Bone Mass N=3791 |

Osteoporotic N=1307 |

p-valuec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO Models: | AUC (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | |

| Hip Fracture | n=14 | n=176 | n=178 | |

| Whole Cohort | ||||

| FRAX with BMDa | 0.78 (0.67, 0.90)e | 0.70 (0.66, 0.73)e | 0.62 (0.58, 0.66) | 0.004d |

| FRAX without BMDa | 0.79 (0.70, 0.88)e | 0.66 (0.61, 0.70)f | 0.63 (0.59, 0.67) | 0.006 |

| Age+Prior Fracture | 0.78 (0.69, 0.87)e | 0.66 (0.62, 0.70)f | 0.65 (0.61, 0.70) | 0.04 |

| Age+BMD | 0.71 (0.58, 0.83)f | 0.70 (0.66, 0.74) | 0.65 (0.61, 0.70) | 0.22 |

| Age alone | 0.69 (0.55, 0.83) | 0.65 (0.61, 0.69) f | 0.64 (0.60, 0.69) | 0.82 |

| No Prior Fracture | ||||

| FRAX with BMD | 0.74 (0.47, 1.00) | 0.71 (0.66, 0.76) e | 0.62 (0.55, 0.68) | 0.07 |

| FRAX without BMD | 0.82 (0.71, 0.94)e | 0.64 (0.59, 0.70) f | 0.63 (0.57, 0.70) | 0.009 |

| Major Osteoporotic Fractureb | n=71 | n=569 | n=371 | |

| Whole Cohort | ||||

| FRAX with BMDa | 0.64 (0.57, 0.70) | 0.62 (0.59, 0.64) | 0.61 (0.58, 0.64) | 0.75 |

| FRAX without BMDa | 0.62 (0.56, 0.69) | 0.59 (0.56, 0.61)f | 0.61 (0.57, 0.64) | 0.48 |

| Age+Prior Fracture | 0.61 (0.54, 0.68) | 0.60 (0.58, 0.63) | 0.60 (0.57, 0.64) | 0.99 |

| Age+BMD | 0.58 (0.50, 0.65) | 0.63 (0.61, 0.65) | 0.61 (0.57, 0.64) | 0.26 |

| Age alone | 0.52 (0.45, 0.60) f | 0.57 (0.55, 0.60) f | 0.57 (0.54, 0.61) | 0.44 |

| No Prior Fracture | ||||

| FRAX with BMD | 0.60 (0.52, 0.69) | 0.61 (0.57, 0.64) | 0.59 (0.54, 0.64) | 0.93 |

| FRAX without BMD | 0.60 (0.52, 0.69) | 0.55 (0.52, 0.59)f | 0.59 (0.54, 0.65) | 0.32 |

N=6252 subjects for whole cohort and 4097 subjects reporting no prior fracture after age 50; model n’s vary by fracture type due to missing values (for fracture type). FRAX models use calculated FRAX hip and major osteoporotic fracture probabilities compared to actual fractures. All models with BMD use femoral neck BMD.

FRAX hip and major osteoporotic probabilities are used for corresponding fracture outcomes.

Major osteoporotic fractures include hip, clinical spine, wrist and humerus.(6)

p value for overall χ2comparison across BMD categories

p<0.05 for trend across BMD groups

p<0.05 compared to osteoporotic group (pair-wise comparison)

p<0.05 compared to FRAX with BMD model (pair-wise comparison within BMD category)

When analyses were restricted to the 4097 women without prior fracture at the baseline exam for all BMD categories, FRAX prediction (AUC) was similar to the whole cohort, for both fracture types (Table 2). Thus, FRAX discriminated fracture risk, particularly for hip fracture, among women without current evidence of osteoporosis (by BMD or history of fracture)—women one would like to target for primary prevention.

When hip fracture risk was further evaluated among women without prior history of fracture, FRAX models with BMD predicted 10-year probability best among women age 65–75 years at baseline (vs. >75 years old; Table 3). Simpler models (e.g., age+BMD) similarly predicted best in younger women.

Table 3.

FRAX Prediction of Hip Fracture among 4097 Women Without a History of Prior Fracture

| Normal/LBM (n=3441) | Osteoporotic (n=656) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Models if no Prior Fracture History: | AUC (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | |

| Hip Fracture n | 105 | 76 | |

| Age <=75 | |||

| FRAX with BMD | 0.75 (0.69, 0.80) | 0.60 (0.51, 0.70) | 0.01 |

| FRAX without BMD | 0.62 (0.56, 0.69) | 0.60 (0.51, 0.70) | 0.75 |

| Age+BMD | 0.73 (0.68, 0.79) | 0.59 (0.50, 0.69) | 0.01 |

| Age alone | 0.63 (0.57, 0.69) | 0.58 (0.48, 0.67) | 0.34 |

| Age >75 | |||

| FRAX with BMD | 0.66 (0.58, 0.73) | 0.51 (0.41, 0.60) | 0.02 |

| FRAX without BMD | 0.62 (0.53, 0.71) | 0.49 (0.39, 0.59) | 0.06 |

| Age+BMD | 0.69 (0.61, 0.77) | 0.62 (0.52, 0.71) | 0.22 |

| Age alone | 0.51 (0.41, 0.62) | 0.52 (0.42, 0.63) | 0.89 |

N=4097 women without a prior history of fracture. Although the age distribution for the whole cohort was approximately evenly split for age <=75 vs. age >75, for women without a history of fracture there were 3,427 women age <75 and 670 women who were age >75 at baseline. All BMD models use femoral neck BMD.

FRAX Prediction across T-Score BMD increments

Clinically, it is helpful to know not only overall prediction (AUC), but also whether the error is an over- or under-estimation. To better illustrate how the rates of fracture predicted by the FRAX model with BMD compared to actual rates, we evaluated this by 0.5 increments of T-score FN BMD (Figure 1). Hip fracture prediction when using 10-year hip fracture probabilities was very close to actual fracture rates across most BMD increments (Figure 1), consistent with higher AUC values for hip fracture (Table 2). In contrast, FRAX over-predicted major osteoporotic fractures in women with normal and low bone mass when using 10-year major osteoporotic probabilities (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

FRAX predicted 10-year hip probabilities with FN BMD are compared to observed fracture across baseline BMD increments. Observed fractures are plotted as total number of fractures for each BMD T-score group, and BMD distribution of the population is indicated on each graph. FRAX hip probabilities were used to predict hip fracture; major osteoporotic probabilities were used to predict major osteoporotic fractures. Major osteoporotic fractures were defined as hip, clinical spine, wrist and humerus.(6) *p<0.05 by paired t-tests of predicted vs. observed fractures in each respective 0.5 BMD T-score increment.

FRAX Prediction Based on NOF Treatment Guidelines

There were 4464 women (71% of the 6252) who had low bone mass by femornal neck or spine BMD. Based on the FRAX US model version 3.0, nearly half of these 4464 women with low bone mass would be considered high-risk by NOF, and recommended for treatment (Figure 2). Importantly, during the 10 years of follow-up after the SOF baseline exam in 1986–88, osteoporosis treatment was less common and less available (e.g., only ~1% used alendronate prior to the year 10 exam), and thus it is a more ideal population to compare fracture risk to predicted. Interestingly, <10% of LBM women classified as “high-risk” by NOF(7) suffered a hip fracture, and <25% of the high risk (treatment recommended) incurred a major osteoporotic fracture (Figure 2). For those with a history of prior fracture, the proportion recommended for treatment was higher, as well as the percent that developed a fracture (Figure 2, Table 2). The NOF treatment threshold (high-risk) for women with low bone mass was reasonably sensitive at identifying a high proportion of women who would develop fracture (most true positives with few false negatives) but was not very specific in excluding false positives and thus had a low specificity among women with low bone mass (Table 4). Moreover, the positive predictive value of this NOF threshold was very poor (Table 4) for women with low bone mass because of the very high false positive rate.

Table 4.

Proportion of women with Low Bone Mass meeting NOF thresholds for treatment (high-risk)a, and performance characteristicsb of NOF treatment thresholds overall, and based on prior history of fracture

| NOF high-risk; No Fracture | NOF high-risk; Did Fracture | NOF low-risk; No Fracture | NOF low-risk; Did Fracture | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP, % | TP, % | TN, % | FN, % | Sensitivityc | Specificityd | PPVe | NPVf | |

| Whole Cohort | ||||||||

| Hip Fracture | 45 | 4 | 50 | 1 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 0.09 | 0.98 |

| MOF Fracture | 39 | 11 | 46 | 5 | 0.67 | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.90 |

| No Prior Fracture | ||||||||

| Hip Fracture | 35 | 3 | 61 | 1 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.98 |

| MOF Fracture | 31 | 7 | 56 | 6 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.19 | 0.91 |

| Prior Fracture | ||||||||

| Hip Fracture | 65 | 7 | 27 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.30 | 0.09 | 0.97 |

| MOF Fracture | 54 | 18 | 24 | 4 | 0.82 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.86 |

NOF high-risk is low bone mass (T score between −1.0 and −2.5 by femoral neck or spine BMD, n=4,464) and 10 year FRAX (including BMD) probability of fracture of ≥3% for hip or ≥20% for major osteoporotic fracture (MOF).(7)

FP=false positive; TP=true positive; TN=true negative; FN=false negative. For presentation, we rounded group percentages to whole numbers (thus the group total may not be exactly 100%). PPV=positive predictive value; NPV=negative predictive value.(14,15)

Sensitivity, or true positive rate = TP/(TP+FN)

Specificity, or true negative rate = TN/(TN+FP)

PPV = TP/(TP+FP)

NPV = TN/(TN+FN)

DISCUSSION

In this large prospective cohort study of 6252 community-dwelling women age 65 and older, we found that the FRAX model predicted incident hip and major osteoporotic fractures among women with normal and low bone mass, not just those with frank osteoporosis. Overall prediction in each BMD category (normal, low, or osteoporotic) was similar using either FRAX model (clinical risk factors alone or combined with BMD) for all fracture types.

FRAX predicted hip fractures better in women with normal and low bone mass than it did for women with frank osteoporosis by BMD criteria. These results don’t contradict prior data that BMD is a strong risk factor for fracture (hazards ratios are based on sensitivity, not specificity). Moreover, one would hope that a clinical risk model would perform best with overall prediction of sensitivity and specificity (AUC) of fracture risk among those identified as low risk by BMD. Similarly, one would hope a risk model would be useful in women who have not yet manifested fragile bones (by experiencing a fracture after age 50). Indeed, our results suggest that the FRAX model, and assessing additional risk factors, offers particular utility in stratifying fracture risk among women with normal and low bone mass. Importantly, this improved prediction for women with normal and low bone mass was present even among women who had yet to experience a fracture since age 50 (Table 2).

Because BMD (the gold standard) is an excellent discriminator of fracture risk, it is not surprising that hip fractures occurred rarely in women with normal BMD (n=14). However, the majority of hip fractures occurred in women without osteoporosis by BMD (n=190), and the addition of clinical risk factors improved fracture prediction in these women. This improved hip fracture prediction occurred even among women who had not “declared” their fragile bone status with a prior fracture.

Ensrud and others have recently published that FRAX prediction is similar to simpler models for prediction of overall non-spine and spine fracture rates.(8,16–19) One could reasonably argue from our results that BMD (if known) or prior fracture after age 50 (if occurred) are very good (and simple) predictors of fracture risk, including among women with low bone mass. However, our results also suggest that in women for which true primary prevention is sought (i.e., normal or low bone mass and no history of prior fracture), FRAX can offer utility in predicting risk—especially for hip fracture.

We now have excellent evidence that treatment for women who meet BMD criteria for osteoporosis can reduce future fracture risk.(20–23) The data for treatment benefit in women with low bone mass is less compelling, particularly with prevention of non-spine fractures.(20, 22, 24–26) Because women with low bone mass (osteopenia) represent the majority of all postmenopausal women, treating nearly all women to prevent future fractures is cost prohibitive with limited resources and also unnecessarily increases adverse effects in women who are unlikely to receive individual benefit.

Thus, the concept of the FRAX model is desirable to better stratify fracture risk and potential benefit with treatment in women without osteoporosis. Our findings provide insight into how FRAX probabilities (and simpler models) relate to observed risk, especially among women with low bone mass that is not yet osteoporotic. Moreover, our results suggest FRAX can be helpful to stratify risk among women who have not yet experienced a fracture—the target group for primary prevention. Additional evidence about how treatment based on FRAX risk stratification will reduce fracture risk is still needed.

With current NOF guidelines, the majority of postmenopausal women with low bone mass are now recommended for treatment based on the FRAX model probabilities.(7,27,28) Since the publication of Donaldson and colleagues’ report on the high proportion of U.S. women meeting NOF treatment thresholds,(27) the US version of FRAX was updated (version 3.0) to improve overestimation of fracture.(12) Our results that current NOF treatment thresholds (based on FRAX) still identify a large proportion of women with low bone mass as high risk who will not fracture (false positives), more research is needed on how to improve screening women with low bone mass who would benefit from primary prevention (and thus avoid unnecessarily treating a large proportion of women).

Our study has several important strengths. It is a large prospective study of 6252 community-dwelling older women, with rigorous quality control of BMD and other measurements. In addition, retention of survivors is excellent, including fracture ascertainment over the 10 years of follow-up.

Our study also has some potential limitations. All FRAX risk factors were measured at baseline, except baseline BMD which was not available until about 2 years after baseline. However, this is unlikely to provide a bias given our prior evidence on the stability of one measurement of BMD longitudinally as a predictor.(2) Also, our results are in postmenopausal U.S. women age 65 or older, and may not be generalizable to other groups, particularly younger women, who are transitioning through the menopause.

The FRAX models provide a paradigm shift in fracture prevention, as it encourages providers (and patients) to think in terms of absolute fracture risk, as there is no compelling rationale for treating people with low absolute risks of fracture. An important limitation of FRAX is that the evidence of treatment efficacy has come from populations with osteoporosis by BMD criteria.(20–23) Therefore, until treatments are shown to be efficacious in women without osteoporotic BMD, the utility of identifying high fracture risk in women without osteoporosis should still be viewed with caution. Our results that FRAX predicts fractures within all BMD categories, including women with normal bone mass and without prior fracture provides the first step. Treatment trials are also needed, to demonstrate that fractures will be prevented among women identified by FRAX to be high risk but without osteoporotic BMD.

In summary, among older U.S. women we found that the FRAX model predicted hip and major osteoporotic fractures within all BMD categories, including women with normal and low bone mass. Simpler models provided similar risk stratification (e.g., age+BMD) among women with low bone mass. For the large proportion of postmenopausal women for whom osteoporosis primary prevention is sought (normal or low bone mass without prior fracture), more research is still needed on how to reduce the false positive rate (and unnecessary treatment) with FRAX (or other screening tests), while retaining our ability to identify women at high risk of fracture.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the following contributors to this work: Heather Baird for technical assistance, and Martie Sucec for editorial review. TA Hillier had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding Source: This research was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the National Institute on Aging (Public Health Service grants 2 R01 AG027574-22A1, R01 AG005407, R01 AG027576-22, 2 R01 AG005394-22A1, AG05407, AG05394, AR35583, AR35582 and AR35584). The SOF investigators were completely independent of the funding source to design and conduct the study including data collection, management, analysis, interpretation of data, and preparation, review and final approval of the manuscript. It was presented in part at the proceedings of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research Meetings, Montreal, Canada, September 13, 2008.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: JAC is a consultant for Novartis, and has received research funding from Novartis. DCB has received research funding from Novartis, Merck and Amgen. DMB is a consultant for Amgen and has received research funding from Novartis, Roche, Merck, and Amgen.

Contributor Information

Teresa A. Hillier, Email: Teresa.Hillier@kpchr.org.

Jane A. Cauley, Email: JCauley@edc.pitt.edu.

Joanne H. Rizzo, Email: Joanne.Rizzo@kpchr.org.

Kathryn L. Pedula, Email: Kathy.Pedula@kpchr.org.

Kristine E. Ensrud, Email: ensru001@umn.edu.

Douglas. C. Bauer, Email: DBauer@psg.ucsf.edu.

Li-Yung Lui, Email: llui@sfcc-cpmc.net.

Kimberly K. Vesco, Email: Kimberly.K.Vesco@kpchr.org.

Dennis M. Black, Email: dblack@psg.ucsf.edu.

Meghan G. Donaldson, Email: mdonaldson@sfcc-cpmc.net.

Erin LeBlanc, Email: Erin.S.LeBlanc@kpchr.org.

Steven R. Cummings, Email: scummings@sfcc-cpmc.net.

References

- 1.Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, Stone K, Fox KM, Ensrud KE, Cauley J, Black D, Vogt TM. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:767–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503233321202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillier TA, Stone KL, Bauer DC, Rizzo JH, Pedula KL, Cauley JA, Ensrud KE, Hochberg MC, Cummings SR. Evaluating the value of repeat bone mineral density measurement and prediction of fractures in older women: The study of osteoporotic fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:155–160. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, Barrett-Connor E, Miller PD, Wehren LE, Berger ML. Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1108–1112. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.10.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, Johansson H, De Laet C, Brown J, Burckhardt P, Cooper C, Christiansen C, Cummings S, Eisman JA, Fujiwara S, Gluer C, Goltzman D, Hans D, Krieg MA, La CA, McCloskey E, Mellstrom D, Melton LJ, III, Pols H, Reeve J, Sanders K, Schott AM, Silman A, Torgerson D, van ST, Watts NB, Yoshimura N. The use of clinical risk factors enhances the performance of BMD in the prediction of hip and osteoporotic fractures in men and women. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1033–1046. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0343-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanis JA, McCloskey EV, Johansson H, Strom O, Borgstrom F, Oden A. Case finding for the management of osteoporosis with FRAX--assessment and intervention thresholds for the UK. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1395–1408. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0712-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:385–397. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) [Accessed June 16, 2010.];Clinician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Internet [serial online] Available at: http://www.nof.org/professionals/Clinicians_Guide.htm.

- 8.Ensrud KE, Lui LY, Taylor BC, Schousboe JT, Donaldson MG, Fink HA, Cauley JA, Hillier TA, Browner WS, Cummings SR Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. A comparison of prediction models for fractures in older women: Is more better. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009 Dec 14;169:2087–2094. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steiger P, Cummings SR, Black DM, Spencer NE, Genant HK. Age-related decrements in bone mineral density in women over 65. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:625–632. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Looker AC, Johnston CC, Jr, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, Calvo MS, Harris TB, Heyse SP, Lindsay RL. Prevalence of low femoral bone density in older U.S. women from NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res. 1995;10:796–802. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650100517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. [Accessed November 14, 2009.];FRAX release notes. available at http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/FRAX_Release_Notes.pdf. FRAX Website [serial online]

- 12.Ettinger B, Black DM, wson-Hughes B, Pressman AR, Melton LJ., III Updated fracture incidence rates for the US version of FRAX(R) Osteoporos Int. 2009 Aug 25; doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-1032-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: A nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosner B. Fundamentals of Biostatistics. 2. PWS Publishers (Duxbury Press); 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altman DG, Bland JM. Diagnostic tests. 1: Sensitivity and specificity. BMJ. 1994;308:1552. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6943.1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colon-Emeric CS, Lyles KW. Should there be a fracas over FRAX and other fracture prediction tools?: Comment on “A comparison of prediction models for fractures in older women”. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2094–2095. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kauffman RP. ACP Journal Club. Simple models predicted 10-year fracture risk in older women as accurately as more complex FRAX models. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Mar 16;152:JC3–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-6-201003160-02013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tremollieres FA, Pouilles JM, Drewniak N, Laparra J, Ribot Dargent-Molina P. Fracture risk prediction using BMD and clinical risk factors in early postmenopausal women: sensitivity of the WHO FRAX tool. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:1002–1009. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donaldson MG, Palermo L, Schousboe JT, Ensrud KE, Hochberg MC, Cummings SR. FRAX and risk of vertebral fractures: the fracture intervention trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1793–1799. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacLean C, Newberry S, Maglione M, McMahon M, Ranganath V, Suttorp M, Mojica W, Timmer M, Alexander A, McNamara M, Desai SB, Zhou A, Chen S, Carter J, Tringale C, Valentine D, Johnsen B, Grossman J. Systematic review: Comparative effectiveness of treatments to prevent fractures in men and women with low bone density or osteoporosis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:197–213. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-3-200802050-00198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cauley JA, Robbins J, Chen Z, Cummings SR, Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, LeBoff M, Lewis CE, McGowan J, Neuner J, Pettinger M, Stefanick ML, Wactawski-Wende J, Watts NB. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on risk of fracture and bone mineral density: The Women’s Health Initiative randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1729–1738. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.13.1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, Zippel H, Bensen WG, Roux C, Adami S, Fogelman I, Diamond T, Eastell R, Meunier PJ, Reginster JY. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:333–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevenson M, Lloyd Jones M, De Nigris E, Brewer N, Davis S, Oakley J. A systematic review and economic evaluation of alendronate, etidronate, risedronate, raloxifene and teriparatide for the prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Health Technol Assess. 2005;9 doi: 10.3310/hta9220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, Applegate WB, Barrett-Connor E, Musliner TA, Palermo L, Prineas R, Rubin SM, Scott JC, Vogt T, Wallace R, Yates AJ, LaCroix AZ. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial. JAMA. 1998;280:2077–2082. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.24.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wells GA, Cranney A, Peterson J, Boucher M, Shea B, Welch V, Coyle D, Tugwell P. Alendronate for the primary and secondary prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001155.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McCloskey EV, Beneton M, Charlesworth D, Kayan K, deTakats D, Dey A, Orgee J, Ashford R, Forster M, Cliffe J, Kersh L, Brazier J, Nichol J, Aropuu S, Jalava T, Kanis JA. Clodronate reduces the incidence of fractures in community-dwelling elderly women unselected for osteoporosis: Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized study. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:135–141. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donaldson M, Cawthon P, Lui L, Schousboe J, Ensrud K, Taylor B, Cauley J, Hillier T, Black D, Bauer D, Cummings S. Estimates of the proportion of older white women who would be recommended for pharmacologic treatment by the new US National Osteoporosis Foundation guidelines. J Bone Miner Res. 2008 Dec 2; doi: 10.1359/JBMR.081203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dawson-Hughes B, Tosteson AN, Melton LJ, III, Baim S, Favus MJ, Khosla S, Lindsay RL. Implications of absolute fracture risk assessment for osteoporosis practice guidelines in the USA. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:449–458. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0559-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]