Abstract

We examined if height loss in older women predicts risk of hip fractures, other non-spine fractures, and mortality, and whether this risk is independent of both vertebral fractures (VFx) and bone mineral density (BMD) by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry. Among 3,124 women age 65 and older in the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, we assessed the association with measured height change between Year 0 (1986–1988) and Year 15 (2002–2004) and subsequent risk of radiologically confirmed hip fractures, other non-spine fractures, and mortality assessed via death certificates. Follow-up occurred every 4 months for fractures and vital status (>95% contacts complete). Cox proportional hazards models assessed risk of hip fracture, non-spine fracture, and mortality over a mean of 5 years after height change was assessed (i.e, after final height measurement). After adjustment for VFx, BMD and other potential covariates, height loss >5 cm was associated with a marked increased risk of hip fracture (HR 1.50, 95% CI 1.06, 2.12), non-spine fracture (HR 1.48; 95% CI 1.20, 1.83), and mortality (1.45; 95% CI 1.21, 1.73). Although primary analyses were a subset of 3,124 survivors healthy enough to return for a Year 15 height measurement, a sensitivity analysis in the entire cohort (n=9,677) using initial height in earlier adulthood (self-reported height at age 25 [−40 years] to measured height age >65 years [Year 0]) demonstrated consistent results. Height loss >5 cm (2”) in older women was associated with a nearly 50% increased risk of hip fracture, non-spine fracture, and mortality—independent of incident VFx and BMD.

INTRODUCTION

Identifying simple clinical risk factors that predict fracture independent of bone mineral density (BMD) is desirable. Vertebral fractures not only cause height loss, they are a strong predictor of non-spine fractures and mortality.(1, 2) However, most vertebral fractures (VFx) remain clinically undiagnosed,(3) so that many patients who could benefit from osteoporosis treatment are often missed. One large study of middle-aged and older patients found height loss was a risk factor for fractures requiring hospitalization—however, VFx status was not measured.(4)

Hence, it is unclear if height loss with aging, in addition to being an indicator of underlying VFx, could itself be a useful clinical predictor of future fractures. The aim of the current study was to determine if height loss in older women predicts risk of non-spine fractures and mortality, and if this risk is independent of both VFx and BMD.

METHODS

Study Sample

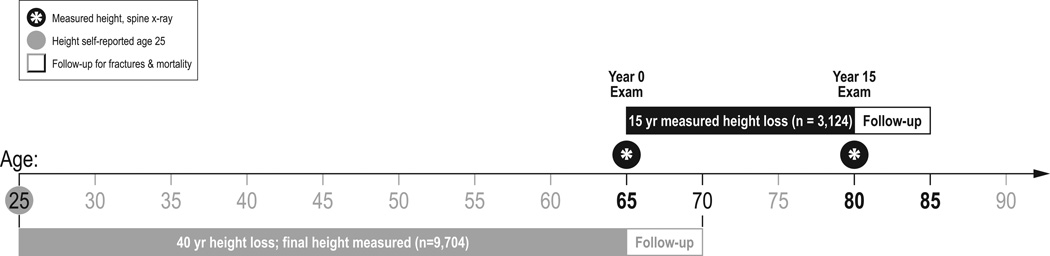

In 1986–88, the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) recruited 9,704 community-dwelling women, who were age 65 or older (>99% Non-Hispanic White), in four U.S. regions: Baltimore County, Maryland; Minneapolis, Minnesota; Portland, Oregon; and the Mononghela Valley near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.(5) Women were recruited irrespective of BMD and fracture history; those unable to walk without assistance and those with bilateral hip replacements were excluded. All women provided written consent, and SOF was approved by each site’s Institutional Review Board. There were 4261 women who participated in the Year 15 exam (88% of survivors). Inclusion criteria for the final analysis was prospective measured height by stadiometer at both Year 0 and the Year 15 exam (n=3,124). A sensitivity analysis was also done in the entire cohort (n=9,704) with historical height change determined by subtracting the height measurement at the Year 0 exam from self-reported height at age 25; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Timeline schematic of the primary analysis with height loss between the Year 0 exam (women age 65 and over) and 15 year follow-up exam (n=3,124; black bar). A secondary height loss analysis was done in the entire cohort (n=9,704; gray bar) using height at age 25 (self-reported at Year 0 exam) and height over 40 years later (measured at Year 0 exam). For comparison, mean follow-up for fractures and mortality was 5 years after height loss in both analyses.

height loss between Year 0 and Year 15

Measurement of Height Loss and Other Measures

Measurement and quality control procedures were rigorous (detailed elsewhere), and included a standardized protocol and clinic site training by the SOF Coordinating Center.(5) Height was measured by stadiometer at both the Year 0 and Year 15 exams, with participants barefoot (or in thin socks). Participants needed to stand with their back, buttocks and both heels against the wall-mounted stadiometer. If participants were obese or had a kyphotic posture that required modification, detailed instructions were given for positioning so that the buttocks, and if possible the scapula, were in contact with the wall-plate, with the legs as close together as possible. Clinic staff verified the participant maintained maximum erect posture after positioning, and that the participant’s head was in the Frankfort Horizontal Plane (in which the lowest point on the inferior orbital margin (orbitale) and the upper margin of the external auditory meatus (tragion) form a horizontal line).

Vertebral fractures were ascertained by morphometric analysis using lateral thoracic and lumbar spine x-rays collected at the Year 0 and Year 15 exams (Figure 1). Prevalent VFx were defined as a height ratio > 3 standard deviations (SD) below the trimmed mean at any vertebral level.(6) An incident VFx on the second x-ray (Year 15) was defined as >20% and at least a 4 mm decrease in vertebral height at any level,(7) and incident fractures were determined over the same 15-year period as height loss.

At the Year 15 exam (2nd height measurement), dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) was measured by Hologic QDR 1000 (Hologic, Bedford, Massachusetts) at the proximal femur (Figure 1). DXA BMD measurement standards and precision have also been previously detailed.(5, 8)

Other potential confounders measured at Year 15 included weight by balance beam scale, smoking and physical activity status (walking for exercise), and self-reported health (excellent/good/fair/poor) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics and outcomes for the primary analysis cohort (n=3,124), stratified by measured height loss over the 15 years since the Year 0 exam

| Height loss > 5 cm (n=649) |

Height loss ≤ 5 cm (n=2,475) |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristicsa | |||

| Year 0 age (years), mean (SD) | 70.2 ± 3.8 | 68.8 ± 3.2 | <0.001 |

| Year 15 age (years), mean (SD) | 85.3 ± 3.8 | 83.7 ± 3.3 | <0.001 |

| Year 0 height (cm), mean (SD) | 160.0 ± 5.6 | 160.1 ± 5.8 | 0.82 |

| Year 15 height (cm), mean (SD) | 153.0 ± 6.1 | 157.3 ± 5.9 | <0.001 |

| Year 0 weight (kg), mean (SD) | 67.8 ± 11.9 | 68.1 ± 12.1 | 0.51 |

| Year 15 weight (kg), mean (SD) | 61.3 ± 11.6 | 66.1 ± 12.5 | <0.001 |

| Walking for exercise | 31.7% | 39.3% | <0.001 |

| Self-reported health (excellent/good) | 71.0% | 77.7% | <0.001 |

| Current smoker | 2.6% | 2.5% | 0.87 |

| Year 0 prevalent vertebral fractureb | 23.8% | 12.7% | <0.0001 |

| Year 15 incident vertebral fracturec | 42.3% | 12.3% | <0.001 |

| Year 0 self-report of non-vertebral fracture after age 50 | 35.6% | 30.0% | 0.007 |

| Year 0 BMD (g/cm2), mean (SD) | 0.75 ± 0.12 | 0.79 ± 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Year 15 BMD (g/cm2), mean (SD) | 0.67 ± 0.14 | 0.74 ± 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Height loss from age 25 to year 0, mean (SD)d | 3.4 ± 2.6 | 2.5 ± 2.4 | <0.0001 |

| Height loss from year 0 to year 15, mean (SD) | 7.0 ± 2.1 | 2.8 ± 1.5 | <0.0001 |

| Outcomes after year 15 height loss measured | |||

| Hip fracture, n (%) | 76 (12.9%) | 148 (6.4%) | <0.0001 |

| Non-spine fracture, n (%) | 193 (32.5%) | 468 (20.0%) | <0.0001 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 302 (46.5%) | 707 (28.6%) | <0.0001 |

| Atherosclerosis | 98 (22.0%) | 252 (12.5%) | <0.0001 |

| Cancer | 32 (8.4%) | 131 (6.9%) | 0.29 |

| Non-athero/non-cancer | 172 (33.1%) | 324 (15.5%) | <0.0001 |

“Year 0” SOF exam is when initial height measured, and some Year 0 exam characteristics are reported for reference. Unless specified otherwise, characteristics are measured at Year 15 exam (Year 15 is the “baseline” for this analysis as it’s both when final height measured and when follow-up for fractures and mortality began).

Year 0 prevalent morphometric vertebral fractures on spine x-ray

Year 15 vertebral fractures are incident morphometric vertebral fractures that developed on repeat spine x-ray over the same 15 year interval as the height loss

As for all of Table 1, these means are in the primary analysis cohort (n=3,124)

Follow-up for Ascertainment of Fractures after Height Loss

After the Year 15 exam, participants were contacted every four months by postcard (with phone follow-up for non-responders) to ascertain incident hip, non-spine fractures, and mortality, for a mean follow-up of 5.2 years through August 2009 (Figure 1); more than 95% of these contacts were completed. Incident hip and non-spine fractures were physician-adjudicated from radiology reports; mortality was determined from death certificates.

Statistical Analyses

We evaluated the distribution of height loss over 15 years, with our outcomes of interest (hip fracture, non-spine fracture, and mortality), both continuously and in categories. On average there was a mean height loss of 3.65 cm over 15 years among the 3,124 women; 47 women had a height change >0 cm, and 29 (0.9%) measured >1 cm taller on repeat exam. We chose clinically meaningful categories using the distribution of height loss. The relationship between height loss and outcomes increased across height loss categories, but was greatest in women with the most height loss (>5 cm). Height loss of >5 cm was also about 2 SD of overall height change (1 SD=2.36 cm loss) in the analytic cohort. Moreover, 5 cm represented the top quartile of height loss (the exact 75%ile was 4.67 cm). Hence, we used height loss >5 cm vs. ≤5 cm for all final analyses.

Although the interaction term between height loss and incident vertebral fracture was not statistically significant (p>0.05) for any of our outcomes (hip fracture, non-spine fracture, or mortality), we also stratified analyses by incident vertebral fracture to illuminate any possible unexpected trends. These analyses confirmed our hypotheses that height loss is a predictor of fractures and mortality independent of incident vertebral fracture.

We used student’s t-tests and χ2 tests to compare means and proportions between height loss groups (Table 1). All the statistical tests that we report are two-sided; the term statistically significant implies a p-value <0.05. Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate the risk of hip fracture, non-spine fracture, and mortality associated with height loss (Tables 2 & 3). We considered variables for inclusion in multivariate models if they were related to height loss (such as age, weight, walk for exercise) or fracture (such as smoking, self-reported health) with an age-adjusted p-value of less than 0.05. We did separate multivariate models of fracture and mortality, adjusting for potential confounders. We then assessed the impact of additional adjustment for VFx and BMD. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System® version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Table 2.

Risk of fracture with measured height loss > 5 cm between Year 0 and Year 15 exam (n=3,124)

| Hip fracture | Non-spine fracture | Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total events | n=224 | n=661 | n=1,009 |

| Models:a | Hazard ratios (95% CI) | ||

| Multivariate | 1.87 (1.40, 2.50) | 1.68 (1.41, 2.00) | 1.45 (1.30, 1.73) |

| Multivariate + VFxb | 1.63 (1.16, 2.29) | 1.54 (1.25, 1.88) | 1.44 (1.21, 1.71) |

| Multivariate + VFxb + BMDc | 1.50 (1.06, 2.12) | 1.48 (1.20, 1.83) | 1.45 (1.21, 1.73) |

All models adjusted for Year 15 exam age, weight, smoking, walking for exercise, and self-reported health (excellent/good vs. fair/poor); mean follow-up for fractures and mortality was 5 years after the Year 15 exam; follow-up for fractures and mortality occurred during years 15–20.

VFx = incident vertebral fracture over same interval that height loss was measured

BMD = bone mineral density by DXA at Year 15 exam

Table 3.

Risk of fracture with height loss >5 cm over 40 years, assessed at Year 0 exam (Using self-reported age 25 height as initial height; N=9,704)

| Hip Fracture | Non-spine Fracture | Mortality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total events | n=228 | n=1554 | n=700 |

| Models:a | Hazard Ratios (95% CI) | ||

| Multivariate | 1.70 (1.29, 2.25) | 1.36 (1.21, 1.52) | 1.34 (1.13, 1.58) |

| Multivariate + VFxb | 1.40 (1.04, 1.87) | 1.22 (1.09, 1.38) | 1.31 (1.11, 1.56) |

| Multivariate + VFxb + BMDc | 1.08 (0.76, 1.54) | 1.15 (1.01, 1.32) | 1.41 (1.09, 1.83) |

All models adjusted for Year 0 age, weight, smoking, walking for exercise, and self-reported health (excellent/good vs. fair/poor); mean follow-up for fractures and mortality was 5 years after the Year 0 exam (to allow comparison of the analytic cohort with similar follow-up time)

VFx = prevalent vertebral fracture at Year 0 exam (when final height measured)

BMD=bone mineral density by DXA at Year 2 exam

Additional Sensitivity Analyses

Sub-sample with kyphosis measures

To evaluate whether height loss could be a surrogate for kyphosis, not captured with assessing incident spine fracture, we analyzed fractures and mortality in a random sub-set of 822 women who also had detailed Cobb measurements of kyphosis(9) at Year 15 as part of a SOF ancillary study (26.3% of the Year 15 sample), and evaluated their fracture and mortality risk after Year 15, adjusting for Cobb angle. The Cobb angle measure of kyphosis is calculated from lateral spine radiographs by drawing a line at the border of the vertebral body that corresponds to the beginning of the thoracic curve (commonly T4) and at the vertebra that corresponds to the interface between the thoracic-lumbar curves (T12 was used in this study). Perpendiculars are drawn from these two lines and the angle at the intersection of these two lines is the Cobb angle.(10, 11)

Height loss in entire cohort (retrospective self-reported height at age 25 to measured Year 0)

To determine if the relationships we observed for measured height loss in older women would be similar using a less precise self-reported initial height, we calculated height loss in the entire cohort of 9,704 women between age 25 (self-reported retrospectively at Year 0 exam) and more than four decades later (measured height at Year 0 exam); see Figure 1. Fracture and mortality follow-up was limited to 5 years after the Year 0 height measurement (when height loss calculated), to match the same follow-up period for our primary analysis (Figure 1). All measures for this full-cohort sensitivity analysis were collected at Year 0, except for DXA BMD, which was first measured 2 years after Year 0 (1988–1990).

RESULTS

The characteristics of the 3,124 women are shown in Table 1, stratified by height loss between Year 0 and the Year 15 exam (Table 1). At initial height measurement (Year 0), there was no difference in measured height for women who would develop >5 cm height loss compared with those who would have ≤5 cm height loss over 15 years (p=0.82).

Over a mean follow-up of 5.2 years after the Year 15 exam, 224 women incurred a hip fracture, and 661 a non-spine fracture; 1009 women died. The overall rates for fracture and mortality were up to two-fold higher among women with height loss >5 cm (Table 1). The absolute mortality rate over 5 years was nearly 50% with height loss >5 cm, compared to ~30% in those with height loss ≤5 cm (Table 1). There was no difference in cancer mortality between the height loss groups, but there was a significant doubling in death rates for both atherosclerosis and non-atherosclerosis/non-cancer categories (Table 1). We further evaluated the most prevalent specific causes of death within the non-atherosclerosis/non-cancer group. Height loss >5 cm increased the risk nearly 800% for osteoporosis/hip fracture death compared to women with height loss ≤5 cm (2.3% vs. 0.3%; p<0.0001). Death from pneumonia, COPD, valve disorders, and cognitive function were also 2–3 fold higher for women with height loss >5 cm compared to those with height loss ≤5 cm (p<0.05 for all causes). Death from sepsis did not differ by height loss groups (0.9% vs. 0.8%, p=0.98)

When height loss was assessed continuously, for each SD of height loss (2.36 cm), there was about a 20% increased adjusted risk for hip fracture (adjusted HR 1.19; 95% CI: 1.01, 1.39); non-spine fracture (adjusted HR 1.14; 1.03, 1.25); and mortality (adjusted HR 1.21; 1.12, 1.31) [all models adjusted for Year 15 age, weight, smoking, walking for exercise, self-reported health, and incident VFx over the same 15-year period as the height loss]. After additional adjustment for Year 15 BMD, this linear relationship was attenuated to borderline significance for hip (1.11; 95% CI 0.94, 1.31) and non-spine fracture (1.10; 0.99, 1.21), but not for mortality (1.21; 1.11, 1.30).

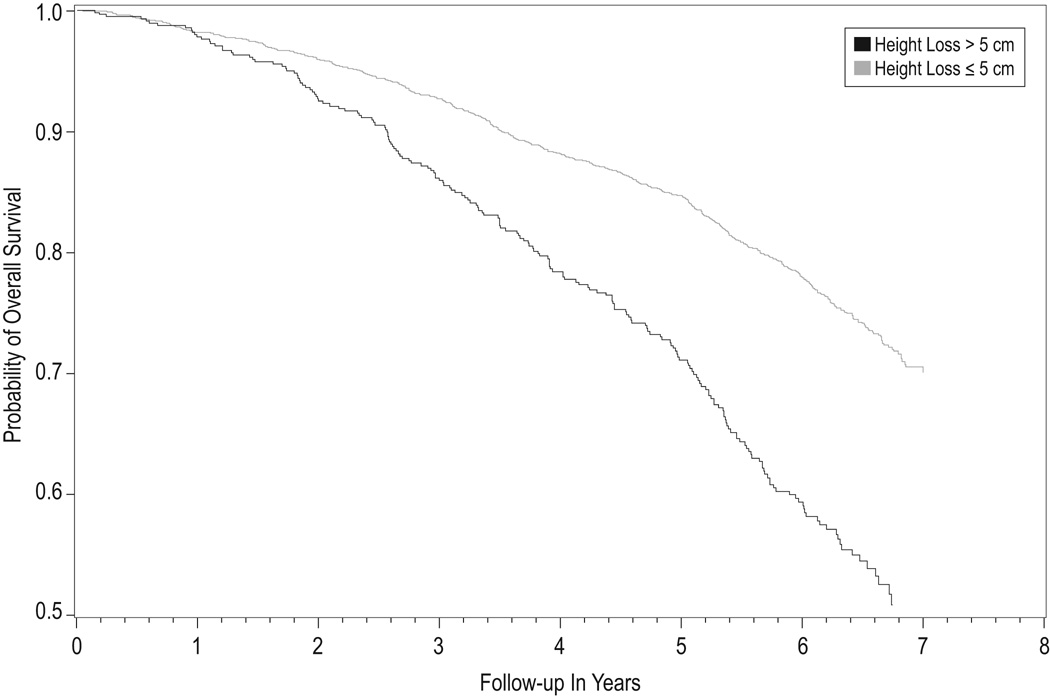

The risk for hip fracture, non-spine fracture, and mortality were all greater among those with >5 cm height loss, compared with those with ≤5 cm of height loss (Table 2). Specifically, after multivariate adjustment for Year 15 age, weight, smoking, walking for exercise, and self-reported health, women with height loss >5 cm had nearly a two-fold increased risk of hip fracture compared with women with height loss ≤5 cm (HR 1.87, 95% CI 1.40–2.50). This increased risk remained significant even after adjustment for incident morphometric VFx (during the same time period as the height loss) and Year 15 BMD (Table 2). Non-spine fracture risk and mortality were both also significantly increased by about 50% in women with height loss >5 cm (Table 2, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cox proportional hazard model for risk of overall mortality in women with height loss >5 cm over 15 years (between Year 0 and 15) compared with women with height loss ≤5 cm. Model is adjusted for age, weight, smoking, walking for exercise, and self-reported health (excellent/good vs. fair/poor), incident VFx during the same period as height loss, and BMD (n=3,124 total women). Mean follow-up for mortality after measured height loss is 5.2 years.

Sensitivity Analyses in the Primary Analysis Cohort with Measured Height Change

Height loss >5 cm remained a similarly significant independent predictor with separate models that evaluated prevalent fracture (instead of incident fracture) at the Year 15 exam for hip fracture, non-spine fracture and mortality (data not shown). Moreover, when we evaluated Cobb angle in the subset of 822 with available kyphotic measures at Year 15, results were similar to the entire Year 15 cohort sample without kyphosis adjustment (n=3,124), suggesting that neither VFx nor kyphosis are the entire explanation for height loss predicting fractures and mortality.

Sensitivity Analyses in the Entire Cohort

To evaluate if height loss >5 cm would remain an independent predictor if initial height was self-reported (and in an earlier stage in life), we did parallel analyses with the entire cohort assessing height loss over more than 40 years (Figure 1). About 1 in 4 women had height loss > 5 cm (2,322 of 9,677 with both height measures, or 24%). Among women with height loss >5 cm, the number (%) that developed hip fracture, non-spine fracture and mortality were 102 (4.6%), 480 (22.4%), and 266 (11.5%), respectively. In contrast, the 7,355 women with height loss ≤5 cm had about half the risk of hip fracture, non-spine fracture, and mortality (1.7%, 15.6%, and 5.9%, respectively, p<0.001 for all outcomes between height loss groups).

Thus, although the absolute risk of fracture and mortality associated with height loss earlier in life was expectedly lower at a younger age, the relative risk associated with height loss >5 cm was similar to what was observed in the primary cohort (Table 1). Moreover, even after multivariate adjustment, the risks were similar (Tables 2 vs. 3). BMD was also a strong predictor of fracture and mortality in the entire cohort; it attenuated the risk of hip fracture, so it was no longer significant among these women at a younger age (Table 3; HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.76, 1.54).

DISCUSSION

In this large US cohort study of 3,124 community-dwelling women age 65 and older, we found that measured height loss of >5 cm (or about 2 inches) was associated with a nearly 50% increased risk of hip, total non-spine fracture, and mortality. This increased risk remained significant even after adjustment for both incident morphometric VFx (over the same time-period as height loss) and BMD. As height measurements are relatively easy and inexpensive to obtain in any clinical setting, our results suggest that height loss (>5 cm) in older women is a simple yet robust measured predictor of increased fracture risk.

Moreover, height loss >5 cm was still a significant independent predictor of non-spine fracture even when the initial height was self-reported maximum adult height (age 25). These findings suggest that assessing height loss (by asking self-reported early adult height) is valuable, even when measuring an older woman’s height for the first time.

One prior large cohort of men and women age 42–82 found that annual height loss of >1 cm/year was associated with an increased risk of hip and non-spine fracture (n=390 fractures); however, VFx status was unknown in this study and could have been the underlying explanation for their findings.(4) Another recent study found that height loss of >3 cm over 20 years (vs. 1 cm) was associated with a significant increased risk of mortality (adjusted RR 1.45) and incident coronary heart disease (adjusted RR 1.42) in older men; again, VFx status was unknown.(12) To our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating the association between height loss and mortality in women.

Previous work in SOF has demonstrated that increased kyphosis is associated with self-reported height loss in a cross-sectional analysis.(13) Furthermore, while increased kyphosis has been associated with an increased risk of fractures(14) and mortality,(15) and we also observed measures of kyphosis to be an independent predictor of these outcomes, adjustment for kyphosis in the sub-sample revealed similar results as the models in the full cohort without kyphosis. Thus, kyphosis does not appear to entirely explain the increased risk of height loss we observed to predict fractures and mortality.

We found that women with height loss > 5cm had more than a three-fold risk of incident VFx over the same time period (Table 1), using the “gold” standard of morphometric radiographic measurement. However, VFx alone also did not fully explain the increased risk of future non-spine fracture and mortality associated with height loss.

Why would height loss be associated with overall mortality, independent of VFx? Height loss represents aging of not only bone but also cartilage (e.g. intervertebral discs), muscle, and joints. Intervertebral discs are responsible for about 25% of the spinal column height and also degenerate variably due to many factors including aging, biomechanical loading, and changes in the estrogen milieu with menopause.(16–18) Height loss might also contribute to mortality due to compression of internal organs (reduced vital capacity, early satiety, etc). Finally, it is possible that height loss represents an overall sign of accelerated aging, as women with height loss > 5cm also had evidence of poorer health (Table 1). However, even after adjustment for these potential confounders, height loss remained an independent predictor of mortality.

Frailty alone is unlikely to explain our findings as a similar increased adjusted relative hazard of mortality associated with height loss was observed among the entire cohort even when the height loss occurred over more than a four-decade span between early adulthood (self-reported age 25) and the Year 0 exam (when women were recruited based on being community-dwelling and ambulatory). Over a similar mean 5-year follow-up period, the absolute mortality rate after height loss>5 cm was expectedly lower in the entire cohort after the Year 0 exam (11.5%), compared with almost half (48.5%) of women after the Year 15 exam who were then a mean age of 84. However, the adjusted relative hazard of mortality with height loss >5 cm was increased by >40% in both groups (Tables 2 & 3). Additionally, even we excluded women who developed incident vertebral fracture over the same 15 years of measured height loss, adjusted relative risk of mortality associated with height loss >5 cm remained significantly increased by ~50% (data not shown). Finally, when we evaluated cause-specific mortality in the main sample (n=3,124), we found an increased risk for most all common causes of death, except cancer and sepsis. Height loss >5 cm had the greatest increased relative risk (8-fold) for hip fracture/osteoporosis death. Thus, our results suggest that height loss >5 cm may be an excellent measurement of overall vital status among women age 65 and older, and irrespective of vertebral fracture status. Our results also suggest that identifying older women with height loss >5 cm may provide an opportunity to intervene for osteoporosis prevention (both fracture and associated mortality).

Clinical Implications

Most VFx, the hallmark of osteoporosis, remain clinically undiagnosed. As such,(3) many patients who could benefit from effective osteoporosis treatments are often missed. Among 9,704 community-dwelling older U.S. women in the SOF study marked height loss (>5 cm, or about two inches), which occurred in about 25% of the sample, was associated with increased risk of hip fractures, non-spine fractures and mortality, even after adjustment for concurrent VFx and BMD.

As height can be readily measured accurately and inexpensively in most any clinical setting, our results suggest that height loss (>5 cm) in older women is a simple yet robust measured predictor of increased fracture risk. Moreover, our results also imply that even if an older women is in clinic for her first height measurement, identifying height loss >5 cm (by asking her height at age 25) is an important predictor of her increased fracture risk.

Although our results were independent of VFx and BMD, these were still two important independent risk factors for height loss. Moreover, BMD was such a strong predictor of hip fracture in the younger women that it attenuated their risk to non-significance (Table 3). Since under-treatment of osteoporosis is widely documented, even with the availability of effective medications, height loss assessment may prove to be another avenue of increasing osteoporosis awareness for further evaluation that could be cost-effective and readily applied in the clinic setting.

Future Research

Presumably height loss itself is not modifiable. We are not aware of any intervention studies to improve or stabilize height (and health) by conditioning or core strength training (such as yoga) in healthy older adults. However, an intriguing recent randomized trial among older adults with adult-onset hyperkyphosis found an intervention of yoga significantly improved two kyphotic measurements, along with a small (0.3 cm) increase in standing height, even among these adults with pre-existing kyphosis.(19) Future studies testing whether exercise that includes spinal strengthening and flexibility could also help maintain height and improve health among any older woman identified with height loss are appealing. As we await such studies, recommending exercise to increase strength, flexibility, and balance among women identified with height loss is unlikely to cause harm and has the potential for other benefits (including fall prevention in these women at higher risk of fracture).

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several important strengths. It is a large US study of community-dwelling older women, with measured height loss over 15 years, and rigorous quality control of morphometric VFx and BMD measurements. In addition, retention of survivors is excellent, and SOF has meticulously collected information regarding incident fractures and mortality.

Our study also has some limitations. Our results were in older, primarily Caucasian women, and may not be generalizable to other ethnic groups, men or younger women. Moreover, our primary analyses were in a subset of survivors healthy enough to return for the Year 15 height measurement. However, our consistent findings using self-reported height at age 25 to the Year 0 exam in the entire cohort (n=9,704) suggest that height loss > 5 cm is a significant risk factor for non-spine fracture and mortality across the lifespan of women. Moreover, height loss remains a significant risk factor for fracture, even when self-reported height at age 25 is used as a surrogate for baseline height.

Summary

We found that height loss >5 cm in older women was associated with an approximately 50% increased risk of non-spine fracture and mortality—independent of incident vertebral fractures (over the same time period) as well as DXA BMD. Less expensive and easier to measure in most clinic settings than DXA BMD or lateral spine radiographs, height loss could be a helpful initial assessment of potential future fracture risk that requires further examination. Assessment of height loss is not intended to supplant BMD measurement but is a tool available, by measuring height accurately, at essentially any clinic visit. Thus, in addition to increased age, low bone density, and history of vertebral fracture, height loss of over 5 cm (2”), even if assessed by history, should alert the astute clinician that this patient may be at particularly high risk for future fracture, and even earlier mortality.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to thank the following contributors to this work: Heather Baird for technical assistance, and Martie Sucec for editorial review.

Funding Source: This research was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases and the National Institute on Aging (Public Health Service grants 2 R01 AG027574-22A1, R01 AG005407, R01 AG027576-22, 2 R01 AG005394-22A1, AG05407, AG05394, AR35583, AR35582 and AR35584). The SOF investigators were completely independent of the funding source to design and conduct the study including data collection, management, analysis, interpretation of data, and preparation, review and final approval of the manuscript. It was presented in part at the proceedings of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research Meetings, Denver, Colorado, September 12, 2009.

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest:

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest relevant to the manuscript topic.

Authors’ Contributions:

Study design: TAH, LL and SRC. Study funding, conduct, and data collection: TAH, JAC, KEE, MCH, and SRC. Data analyses: LL. Drafting manuscript: TAH. Data interpretation, including critical revision and final approval of manuscript: TAH, LL, DMK, ESL, KKV, DCB, JAC, KEE, DMB, MCH, SRC. TAH takes responsibility for integrity of the manuscript, including data analyses.

Contributor Information

Teresa A. Hillier, Email: Teresa.Hillier@kpchr.org.

Li-Yung Lui, Email: LLui@sfcc-cpmc.net.

Deborah M. Kado, Email: DKado@mednet.ucla.edu.

ES LeBlanc, Email: Erin.S.LeBlanc@kpchr.org.

Kimberly K Vesco, Email: Kimberly.K.Vesco@kpchr.org.

Douglas C. Bauer, Email: DBauer@psg.ucsf.edu.

Jane A. Cauley, Email: JCauley@edc.pitt.edu.

Kristine E. Ensrud, Email: ensru001@umn.edu.

Dennis M. Black, Email: DBlack@psg.ucsf.edu.

Marc C. Hochberg, Email: mhochber@medicine.umaryland.edu.

Steven R. Cummings, Email: scummings@sfcc-cpmc.net.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kado DM, Browner WS, Palermo L, Nevitt MC, Genant HK, Cummings SR. Vertebral fractures and mortality in older women: a prospective study. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1215–1220. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.11.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black DM, Arden NK, Palermo L, Pearson J, Cummings SR. Prevalent vertebral deformities predict hip fractures and new vertebral deformities but not wrist fractures. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:821–828. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, O'Fallon WM, Melton LJ., III Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures: A population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1985–1989. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:221–227. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moayyeri A, Luben RN, Bingham SA, Welch AA, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT. Measured height loss predicts fractures in middle-aged and older men and women: The EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:425–432. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:767–773. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503233321202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cauley JA, Palermo L, Vogt M, et al. DM Prevalent vertebral fractures in black women and white women. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1458–1467. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Black DM, Palermo L, Nevitt MC, Genant HK, Christensen L, Cummings SR. Defining incident vertebral deformity: a prospective comparison of several approaches. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:90–101. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hillier TA, Stone KL, Bauer DC, et al. Evaluating the value of repeat bone mineral density measurement and prediction of fractures in older women: The study of osteoporotic fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:155–160. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.2.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kado DM, Prenovost K, Palermo L, Stone K, Hillier TA, Cummings SR. To what extent do vertebral fractures, disc height loss, low bone density, and poor muscle strength contribute to hyperkyphosis in older women? . J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:S432. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fon GT, Pitt MJ, Thies AC., Jr Thoracic kyphosis: Range in normal subjects. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980;134:979–983. doi: 10.2214/ajr.134.5.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kado DM, Prenovost K, Crandall C. Narrative review: Hyperkyphosis in older persons. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:330–338. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-5-200709040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Lennon L, Whincup PH. Height loss in older men: Associations with total mortality and incidence of cardiovascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2546–2552. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.22.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ettinger B, Black DM, Palermo L, Nevitt MC, Melnikoff S, Cummings SR. Kyphosis in older women and its relation to back pain, disability and osteopenia: The study of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 1994;4:55–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02352262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang MH, Barrett-Connor E, Greendale GA, Kado DM. Hyperkyphotic posture and risk of future osteoporotic fractures: The Rancho Bernardo study. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:419–423. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.051201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kado DM, Lui LY, Ensrud KE, Fink HA, Karlamangla AS, Cummings SR. Hyperkyphosis predicts mortality independent of vertebral osteoporosis in older women. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:681–687. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-10-200905190-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams P, Warwick R. Arthrology. In: Williams P, Warwick R, editors. Gray's Anatomy. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1980. pp. 444–445. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baron YM, Brincat MP, Galea R, Calleja N. Intervertebral disc height in treated and untreated overweight post-menopausal women. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:3566–3570. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin MD, Boxell CM, Malone DG. Pathophysiology of lumbar disc degeneration: A review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;13:E1. doi: 10.3171/foc.2002.13.2.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greendale GA, Huang MH, Karlamangla AS, Seeger L, Crawford S. Yoga decreases kyphosis in senior women and men with adult-onset hyperkyphosis: Results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1569–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]