Abstract

Purpose

A growing body of research documents the significance of siblings and sibling relationships for development, mental health, and behavioral risk across childhood and adolescence. Nonetheless, few well-designed efforts have been undertaken to promote positive and reduce negative youth outcomes by enhancing sibling relationships.

Methods

Based on a theoretical model of sibling influences, we conducted a randomized trial of Siblings Are Special, a group-format afterschool program for 5th graders with a younger sibling in 2nd through 4th grade, which entailed 12 weekly afterschool sessions and 3 Family Nights. We tested program efficacy with a pre-posttest design with 174 families randomly assigned to condition. In home visits at both time points we collected data via parent questionnaires, child interviews, and observer-rated videotaped interactions and teachers rated children’s behavior at school.

Results

The program enhanced positive sibling relationships, appropriate strategies for parenting siblings, and child self-control, social competence, and academic performance; program exposure was also associated with reduced maternal depression and child internalizing problems. Results were robust across the sample, not qualified by sibling gender, age, family demographics, or baseline risk. No effects were found for sibling conflict, collusion or child externalizing problems; we will examine follow-up data to determine if short-term impacts lead to reduced negative behaviors over time.

Conclusions

The breadth of the SAS program’s impact is consistent with research suggesting that siblings are an important influence on development and adjustment and supports our argument that a sibling focus should be incorporated into youth and family-oriented prevention programs.

Keywords: Prevention, Siblings, Family, Human Development, Middle Childhood, Adolescent Behavior, Risky Behavior, Substance Use, Program Outcomes, Evaluation Studies

This study was designed to test a novel approach to promoting youth development and family relationships prior to adolescence, a period of increased risk. Siblings play a key role in each other’s adjustment [1, 2]. Research on children and adolescents reveals concordance between siblings’ adjustment [3,[4, 5], as well as links between sibling relationship qualities (e.g., warmth, hostility) and adjustment in domains including externalizing and internalizing problems, school adjustment, and peer relationships. Further, studies controlling for parent-child and peer relationships, parental characteristics and genetic and other family factors [1, 5-10] document unique variance accounted for by sibling characteristics and relationships. And, sibling effects are robust across social-cultural contexts [11, 12].

Given that middle childhood-aged siblings spend more of their free time with each other than with parents or friends [13], that sibling relationships are emotionally intense, and that sibling conflict is parents’ leading childrearing concern [13, 14], findings documenting the scope and strength of sibling influences are not surprising. With a few notable exceptions [15], however, prevention scientists have not capitalized on sibling influences in efforts to prevent youth behavior problems. Further, although the popular press provides advice to parents on reducing sibling conflict, empirically-validated approaches are rare [16]. To address this gap, we describe the conceptual model and curriculum for a sibling-focused prevention program, Siblings are Special (SAS), and present the results of a randomized control trial implemented with sibling dyads and their parents.

Theoretical Model of Sibling Effects

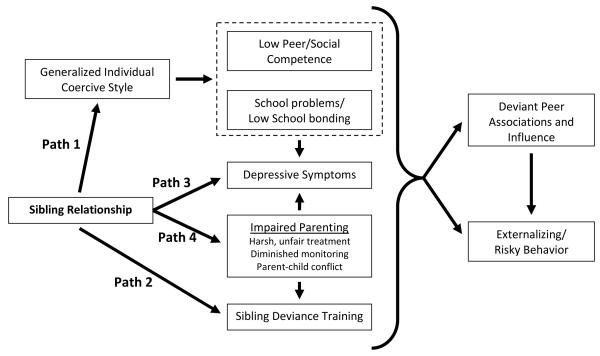

Our model (Figure 1) is grounded in developmental and family research that shows how high negativity and low positivity between siblings lead to adjustment problems. The model includes four pathways that begin with sibling relationship quality, particularly warmth and conflict; we view these pathways as parallel, not mutually exclusive, with links to both proximal and more distal youth outcomes. The first pathway was described in Patterson’s coercive process model [17]: coercion in family relationships represents a “training ground” for the development of a generalized coercive interpersonal style, when children learn that escalating negative behavior is reinforced by social partners who give into their demands. This coercive cycle occurs with parents and in sibling exchanges. In turn, youth who develop coercive interpersonal styles encounter peer difficulties and are perceived negatively by teachers at school [18]. They then affiliate with similar peers [19], with mutual reinforcement of antisocial tendencies.

Figure 1.

onceptual model of pathways from sibling relationship to adjustment problems

Through Path 2, sibling deviance training, siblings collude in opposition to parental authority [10, 20, 21]. In this “partner in crime” dynamic, siblings reinforce each other’s antisocial tendencies and expose each other to risks such as antisocial peers, substance use, and delinquent behaviors [10, 22, 23]. Sibling deviance training may involve positivity between siblings; indeed, a primary index is shared laughter in response to antisocial talk. As such, enhancing positive sibling relationships might be expected to lead to deviance training. The counterargument is that positive sibling exchanges do not have a causal effect on deviance training but are byproducts of the deviance training process [e.g., [24]. Accordingly, we tested whether involvement in SAS increased or decreased sibling deviance training.

Path 3 links sibling conflict and low support to depressive symptoms [1, 25]. Depression is painful, costly, and a risk factor for externalizing problems including by making youth more susceptible to peer pressure or to make efforts to change a negative mood states through substance use. Sibling research has often focused on the negative effects of sibling conflict, but low warmth and support also has negative implications [25, 26].

Path 4 concerns the evocative effects of sibling relationships on parenting. Coercive sibling dynamics are a stressor for parents [13] and disrupt competent parenting [27]. Sibling negativity may increase parental stress and depression, reducing parents’ capacity for monitoring youths’ activities and ability to disrupt peer and sibling deviance training. Stress engendered by sibling conflict also cause parental disengagement, decreased involvement, and inconsistent and harsh parenting, all linked to child adjustment problems [28].

Structural features of sibling relationships (dyad gender composition, birth order, age spacing), may moderate the strength of these paths. Slomkowski et al. [24] suggest that deviance training may be most prominent in brother-brother pairs, and social learning theory holds that youths learn new behaviors and attitudes through exposure to models who are powerful, warm, and similar to themselves such as, older and same sex siblings, and those with warm relationships [7, 11, 24, 29].

The Siblings Are Special (SAS) Program

Siblings Are Special was based on this framework and aimed at preventing behavior problems by enhancing youths’ socio-emotional competencies in the context of their sibling relationships—as well as parents’ ability to manage sibling relationships. We designed the program for middle childhood-aged siblings to promote sibling and family relationships just prior to older siblings’ transition to middle school, a transition marked by increased exposure to and involvement in risky behaviors. SAS combined a series of 12 afterschool sessions for small groups of sibling dyads with 3 Family Nights that included parents. As a universal, school-based intervention focused on siblings, SAS was designed to be non-stigmatizing.

SAS aimed to promote sibling relationship qualities directly and through fostering children’s interpersonal skills and parents’ involvement in the sibling relationship. Specifically SAS aimed to enhance: (1) Sibling relationship qualities, including warmth, a sense of mutual responsibility and joint decision-making regarding shared, constructive activities, while reducing sibling conflict and deviance training (Paths 3 and 4 in Figure 1); (2) Children’s individual socio-emotional competencies, including emotion understanding, self-control, perspective taking, social problem solving, and fair play skills—versus coercive style (some program elements targeting these factors were adapted from the PATHS program [30] and the Fast Track social skills curriculum [31]; Path 1); (3) Parental involvement, including parental mediation of sibling conflict, purposeful non-involvement in sibling conflict when appropriate, knowledge of siblings’ relationship dynamics, and time in shared activities with the dyad and avoidance of authoritarian control [14] (Path 4).

Grounded in this model, we conducted a randomized trial to test the effects of SAS on enhanced sibling relationship qualities, children’s socio-emotional competencies and adjustment, and parental involvement and adjustment.

Method

Participants

Data came from mothers, fathers, and two target siblings in 174 families, drawn from 16 schools in seven rural and urban school districts. School personnel identified families with children in the targeted age range (i.e., one child in the 5th grade and a second child in the 2nd, 3rd, or 4th grade) and sent home letters describing the study. Siblings had to be living in the same household for at least the past three years. Of the 504 families to whom letters were sent, 174 (35%) agreed to participate. At pretest, 38 families did not include father data (six refused; 32 were single-mother families) and three did not include mother data (one refused, two single-father families), resulting in a sample of 136 fathers and 171 mothers.

Reflecting the region, participants were mostly White (79% mothers, 77% fathers), but included African Americans (10% mothers and fathers), and other ethnicities. Median annual family income was $63,750 (M = $68,857, SD = $45,841). These figures approximate the state profile from 2012 U.S. Census Bureau data , (84% White; median household income of $50,398 [32]). The sample included 69% married, 10% cohabiting, and 21% single parents. Older siblings averaged 10.8 (SD = 0.39) and younger siblings averaged 8.59 (SD = 1.33) years of age. Dyad sex constellation was roughly evenly distributed ( 22% sister-sister, 32% older sister-brother, 23% older brother-sister, and 23% brother-brother).

Procedures

Pretest data were collected prior to randomization, and posttest was approximately 4 weeks after SAS ended. In home visits research assistants collected questionnaire data from parents, interviewed each sibling privately, and videotaped family interactions. This study used videotaped data from a 10-minute dyadic sibling interaction in which siblings were asked to plan a party. Ech child’s homeroom or English teacher was asked to complete a mailed survey. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Families were randomly assigned to intervention (n = 88) or control (n = 86) conditions. We found two pretest differences among 20 demographic variables: control (25%) as compared to intervention (10%) fathers were more likely to be non-White, and intervention fathers reported more depressive symptoms (control M = 1.38, SD = 0.33, intervention M = 1.53, SD = 0.51). Thus, all models of father-reported outcomes included non-White status and pretest depression as controls We found one pretest difference among the outcome variables, a less than chance result, which was thus ignored.

To minimize the potential effect of disappointment among control families for not being assigned to the program as well as to test the intervention against a low-cost alternative, families in both conditions received a popular book on parenting siblings [33]. Intervention families participated in SAS, which was delivered by pairs of trained leaders to groups of four sibling dyads. On average, children attended 10.41 (SD = 2.76) of the 12, 1.5 hour after-school sessions. 81% of families attended at least two of three Family Nights that were 2.5 hours long and delivered around the 4th, 8th, and 12th afterschool session. In these sessions parents learned about the perspectives and skills that were being conveyed to children and learned how to generalize intervention-targeted behaviors at home through behavior management and involvement with the dyad [34]. Observer ratings of 25% of the program sessions indicated that the program was delivered with high fidelity, with an average of 80-95% of the curriculum content presented as planned.

At posttest, 19 (11%) of families did not participate. Comparisons revealed no evidence for differential attrition based on demographics, parent and child adjustment, or sibling relationship qualities. An additional seven families at pretest and one family at posttest declined the videotaped observations.

Measures

Measures are described in Table 1, and post-test adjusted means and standard deviations are shown in Table 2. Unless noted, scales were created by averaging item responses, with high scores signifying high values of the construct.

Table 1.

Summary of Study Measures

| Construct | Scale | Sample item | # items | Response scale | Alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sibling relationship | |||||

| Fair play | Fair Play (developed for this project) | “child takes turns when my children play together” | 6 | 1 = never; 5 = always | .85 |

| Warmth | Social Relations Questionnaire subscale [38] |

“you go to your sibling for advice and support” | 8 | 1 = not at all; 5 = very much |

.83 |

| Conflict | Sibling Relationship Inventory [39] | “you feel mad or angry at your sibling” | 5 | 1 = hardly ever; 5 = always |

.75 |

|

| |||||

| Child adjustment | |||||

| Externalizing | Behavior Problems Index [40] | “child has a strong temper and loses it easily” | 20 | 0 = never; 1 = some- times; 2 = often |

.86 |

| Internalizing | Behavior Problems Index [40] | “child feels worthless or inferior” | 10 | Same as above | .77 |

| Self-control | Children’s Self-Control Scale [41] | “child plans ahead before acting” | 8 | 1 = never; 5 = almost always | .88 |

| Social competence |

Social Competence Scale [42] | “child helps, shares, and cooperates with others” | 5 | 1 = almost never; 6 = almost always |

.88 |

| Academic performance |

Academic Performance Rating Scale [43]* |

“what is the quality of the child’s reading skills?” | 10 | 5-point Likert scales b | .95 |

|

| |||||

| Parenting | |||||

| Authoritarian control |

Adapted from [44] | “threaten to punish children to get them to stop fighting” |

4 | 1 = never; 5 = almost always |

.70 |

| Positive guidance |

Adapted from [44] | “you explain one child’s feelings or point of view to the other child” |

8 | Same as above | .85 |

| Non- involvement |

Adapted from [44] | “let your children work out disagreements on their own” |

4 | Same as above | .81 |

| Depressive symptoms |

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale [45] |

“during the last week, I felt lonely” | 20 | 1 = rarely; 4 = most of the time |

.76 |

Note. For measures with multiple reporters and/or multiple targets, the alpha reported in this table is the average alpha across reporters at pretest.

Category 2 and 3 were combined such that 0 = never, 1= sometimes/often.

Items had varied response scale anchors (e.g., 1 = poor, 5 = excellent; 1 = far below grade level, 5 = far above grade level); We added 4 items to the original 6 that rated the child relative to grade level expectations.

Table 2.

Model Adjusted Posttest Means and Standard Deviations for Study Variables, by Intervention and Control Conditions

| Intervention | Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD |

| Sibling relationship | ||||

| Fair play (M) | 3.54 | 0.63 | 3.39 | 0.66 |

| Fair play (F) | 3.57 | 0.58 | 3.50 | 0.62 |

| Sibling intimacy (C) | 3.10 | 0.80 | 3.03 | 0.85 |

| Sibling conflict (C) | 2.36 | 0.76 | 2.23 | 0.80 |

| Sibling negativity (O) | 0.03 | 0.88 | 0.01 | 0.88 |

| Sibling positivity (O) | 0.10 | 0.89 | −0.18 | 0.89 |

| Rule break approval (O) a | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

|

| ||||

| Child adjustment | ||||

| Externalizing (M) | 8.25 | 4.97 | 8.85 | 4.89 |

| Externalizing (F) | 8.50 | 4.90 | 8.50 | 4.51 |

| Internalizing (M) | 2.85 | 2.68 | 3.40 | 2.63 |

| Internalizing (F) | 3.19 | 2.80 | 3.50 | 2.45 |

| Self-control (M) | 3.35 | 0.70 | 3.22 | 0.72 |

| Self-control (F) | 3.38 | 0.63 | 3.24 | 0.62 |

| Social competence (T) | 4.83 | 1.10 | 4.61 | 1.12 |

| Academic performance (T) | 3.53 | 0.82 | 3.44 | 0.84 |

|

| ||||

| Parenting | ||||

| Authoritarian control (M) | 2.96 | 0.57 | 3.03 | 0.63 |

| Authoritarian control (F) | 2.93 | 0.64 | 3.08 | 0.60 |

| Positive guidance (M) | 3.82 | 0.62 | 3.75 | 0.70 |

| Positive guidance (F) | 3.52 | 0.59 | 3.62 | 0.61 |

| Noninvolvement (M) | 3.30 | 0.58 | 3.11 | 0.58 |

| Noninvolvement (F) | 3.09 | 0.49 | 2.90 | 0.62 |

| Depressive symptoms (M)b | 1.47 | 0.40 | 1.64 | 0.55 |

| Depressive symptoms (F)b | 1.40 | 0.38 | 1.43 | 0.31 |

Note. (M) = mother-reported; (F) = father-reported; (T) = teacher-reported; (C) = child-reported; (O) = observed.

Values represent predicted probabilities.

Scores for depressive symptoms were log transformed. Adjusted means from alternative regression model on original scores; significance results based on log-transformed scores.

Sibling relationship qualities were assessed first, via child reports of sibling warmth and conflict using established measures [38,39]. Parents rated each sibling’s fair play using a measure created for this study that was based on behaviors targeted in the intervention, including take turns and be a good sport, Research assistants were trained and supervised in weekly meetings to rate videotaped family interactions according to a coding system adapted from previous research [35-37]. All observations were coded by at least two coders; final scores were created by averaging across raters. Intra-class correlations ranged from .73 to .87 across subscales. We used three observed scores. Sibling positivity was comprised of codes for affection and positive engagement. Sibling negativity was comprised of hostility and bossiness. Sibling deviance training was assessed in terms of each sibling’s positive reaction to rule breaking behavior by the other, including rules associated with the videotape procedure; talk about sex, substance use, or antisocial acts; obscene or aggressive gestures; and collusion against parental authority. Deviance training was a dichotomous indicator: 0 = there was no sibling rule break or the child did not approve of the rule break and 1 = child approved of a sibling rule break. Although coders were given a brief description of the study, they were blind to condition.

Child adjustment was measured through mother and father reports of externalizing behavior, internalizing behavior, and self-control, and through teacher reports of social competence and academic performance. Parenting of the sibling dyad was indexed via parents’ reports of their authoritarian control, positive guidance, and deliberate noninvolvement [44], and parent adjustment was assessed via mothers’ and fathers’ reports of their depressive symptoms [45].

Results

Analysis Plan

To assess program impact, we used an intent-to-treat design, including all families that were randomly assigned at pretest regardless of their level of program participation ( 0 = control condition; 1 = intervention condition). To accommodate missing data in regression models, we used multiple imputation (MI) carried out using SAS’s PROC MI; 40 multiply-imputed datasets were generated for each data source, with key demographic and outcome variables incorporated into the missing data model. Standard procedures were used to combine regression coefficients to assess statistical significance. MI models were carried out on subjects who were recruited into the study; we did not impute data for parents who were not recruited (e.g., fathers who were not in the household at the time of the study). We estimated separate models for mother- and father-reported variables because mother and father reports were only moderately correlated (rs ranged from .16 to .65, median = .53), suggesting that findings could differ across parent.

For outcomes that were not sibling-specific ( parent adjustment, parenting the sibling dyad), we used multiple regression. For outcomes that differed by sibling ( child adjustment, sibling relationship qualities), we used multilevel models (MLM) to accommodate interdependence (siblings nested within families). Preliminary MLMs including school as an additional level of clustering revealed little variance at the school level. Therefore, we tested program impacts using 2-level MLMs that included a random intercept to represent family clustering. For all models with sibling-specific outcomes, we assessed differential intervention impact on older versus younger siblings by including a birth order X condition term. No significant effects emerged, so the term was removed from final models. For teacher reports of academic performance, there was little family-level variance, so we used a regression model with standard errors adjusted for non-independence. All models controlled for the pretest measure of the outcome, birth order, child age, child gender, and income; models for father-reported outcomes also included father depressive symptoms and non-White status to account for condition differences at pre-test. We also examined potential moderators of intervention impact, including income, child gender, and initial risk status, but found no consistent effects (results not described).

Intervention Effects

Sibling relationships

Table 3 shows results of the tests of the intervention. Intervention mothers reported significantly more fair play at post-test, controlling for pretest. In addition, coders rated intervention children as exhibiting more sibling positivity than control children. There was no significant intervention effect on observed rule-break approval or child rated conflict or warmth.

Table 3.

Results for Intervention Effects

| Outcome | B | SE | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sibling relationship | |||

| Fair play (M) | 0.15* | 0.06 | 0.34 |

| Fair play (F) | 0.03 | 0.08 | --- |

| Sibling intimacy (C) | 0.07 | 0.09 | --- |

| Sibling conflict (C) | 0.13 | 0.08 | --- |

| Sibling negativity (O) | 0.01 | 0.10 | --- |

| Sibling positivity (O) | 0.28* | 0.13 | 0.32 |

| Rule break approval (O)a | 0.41 | 0.82 | --- |

|

| |||

| Child adjustment | |||

| Externalizing (M) | −0.59 | 0.41 | --- |

| Externalizing (F) | 0.01 | 0.59 | --- |

| Internalizing (M) | −0.55* | 0.22 | 0.31 |

| Internalizing (F) | −0.32 | 0.33 | --- |

| Self-control (M) | 0.12* | 0.06 | 0.24 |

| Self-control (F) | 0.14* | 0.07 | 0.29 |

| Social competence (T) | 0.22** | 0.08 | 0.32 |

| Academic performance (T) | 0.08* | 0.04 | 0.24 |

|

| |||

| Parenting | |||

| Authoritarian control (M) | −0.07 | 0.09 | --- |

| Authoritarian control (F) | −0.15 | 0.11 | --- |

| Positive guidance (M) | 0.07 | 0.09 | --- |

| Positive guidance (F) | −0.10 | 0.09 | --- |

| Noninvolvement (M) | 0.19* | 0.09 | 0.27 |

| Noninvolvement (F) | 0.19* | 0.09 | 0.29 |

| Depressive symptoms (M) | −0.10** | 0.03 | 0.23 |

| Depressive symptoms (F) | −0.03 | 0.04 | --- |

Note. (M) = mother-reported; (F) = father-reported; (T) = teacher-reported; (C) = child-reported; (O) = observed.

Log-odds coefficient from multi-level logistic regression.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Child adjustment

Based on mother report, children in the intervention condition, compared to control children, had significantly lower levels of internalizing problems at posttest, controlling for pretest levels, mothers and fathers reported that intervention children had higher levels of self-control at post-test than control children, and teachers reported that intervention children had significantly higher social competence and academic performance There were no significant intervention effects on child externalizing behavior or father- or teacher-reported internalizing behavior.

Parenting of the sibling dyad and parent adjustment

Intervention parents reported significantly more non-involvement in their children’s arguments compared to the control parents but there were no program effects on parents’ authoritarian control or positive guidance. Intervention mothers reported significantly fewer depressive symptoms at post-test than control mothers, but there were no effects for fathers.

Discussion

This study represents one of the few randomized trials ever conducted to harness the power of sibling relationships to foster youth adjustment. To our knowledge, this is the only sibling-relationship focused prevention trial to use a universal approach ( not limited to high risk youth) to promote youth adjustment and family dynamics in middle childhood. As such, it represents a starting point for efforts to integrate sibling relationships into prevention programming aimed at supporting families and youth who are heading into the high-risk period of adolescence.

The results evidence the promise of a sibling-focused prevention program. Based on intent-to-treat analyses, we found significant program effects for child adjustment as well as dimensions of sibling relationship quality, parent adjustment, and parenting of siblings. The breadth of the SAS program’s impact is consistent with research suggesting that siblings are an important influence on youth adjustment and on larger family dynamics and supports our argument that a sibling focus should be incorporated into youth and family-oriented prevention programs.

Results were not consistent across all outcome variables, leaving room for improving SAS. For example, although mother and observer ratings showed a significant program impact we found no effects on child or father reports or observer ratings of sibling conflict and collusion. Rates of conflict and collusion were low at Time 1, suggesting a possible floor effect. With respect to mother-father differences, mothers’ generally higher level of involvement in parenting may mean that they were more sensitive to the effects of the intervention.

Of our conceptual model’s four proposed pathways of sibling influence, SAS had the most consistent effects on children’s positive (vs. coercive) interpersonal styles, sibling positivity, and the pathway through which sibling dynamics engender parental stress and low quality parenting. With respect to the first pathway, effects on youth social competence (teacher report) and self-control (parent report) were likely due to the fact that these were direct targets of program activities; as our model suggests, such competencies also may have been reinforced in the context of positive sibling social exchanges. Teachers also reported that intervention children showed relatively better academic performance at post-test, perhaps due to their enhanced socio-emotional skills. Such an interpretation would be consistent with pathway one, linking a positive interpersonal style to stronger school attachment and functioning.

We found no evidence of program impact on sibling approval of rule-breaking behavior, an indicator of sibling deviance training, representing the second pathway in the model. Prior research on deviance training has focused on clinical samples, and as with sibling conflict, the low rates observed in our sample may represent a floor effect. However, we also did not find negative (iatrogenic) effects of the program as there was no evidence of increased deviance training. With respect to the third pathway, consistent with our conceptual model and prior correlational studies, the positive changes in the sibling relationship in intervention children may have had implications for the decreases in child depressive symptoms that we also observed.

Turning to the fourth pathway, maternal depressive symptoms were reduced among SAS families. Prior research documents that sibling dynamics are a source of parental stress, and thus SAS program effects on sibling relationship positivity may underlie this positive change in mothers’ mental health. Depression is linked to irritability and emotional reactivity, and program effects on parental non-involvement suggest that both mothers and fathers were able to trust their children to work out their problems on their own. This may have been due to children’s enhanced socio-emotional competencies and more positive sibling relationships and diminished depression also may have allowed mothers to remain non-reactive in the face of sibling conflict. We are unable to tease apart the possible pathways involving sibling relationships, parent adjustment, and parenting with our current data, but with additional waves we will be able to test these and other meditational pathways suggested by our conceptual model.

We found no program effects for sibling conflict, a construct central to several pathways in our model. As noted, the absence of effects on sibling conflict may be due to the low base rate. In the interaction task sibling conflict was rare, and parents’ ratings of conflict were below the midpoint of the scale, giving rise to the possibility of floor effects. Moreover, there was substantial stability across waves (correlations range from .49 to .72), limiting the potential for intervention effects. Thus patterns of sibling conflict have considerable inertia, and a more sustained or a refined manner of working with parents may be needed to foster change.Alternatively including a more refined measure of conflict that focuses on resolution processes (e.g., problem solving; compromise) may be a direction for future research.

The absence of condition differences in sibling conflict also should be viewed in light of the increases in parental non-involvement: The fact that intervention parents allowed their children to solve their problems on their own to a greater extent may imply that the sibling conflicts that did occur in intervention condition dyads were less intense and more manageable. As noted, in future tests of SAS it will be important to examine sibling conflict in a more nuanced way, including its subject matter and intensity. It also will be important to determine whether sibling conflict decreases over a longer timeframe due to the accumulating effects of youths’ improved socio-emotional competencies and positive sibling dynamics.

We found no consistent moderating effects of sibling birth order or gender or of family income, suggesting that the effects of the intervention were robust across the sample. The sample size was relatively small, however, and future research with larger samples will be needed to test the moderating role of structural factors.

Taken together, findings of SAS program effects on child adjustment and family dynamics demonstrate the promise of a focus on siblings for prevention programming. Data on program attendance— children attended more than 10 of the 12 afterschool sessions on average and 81% of families attended at least two Family Nights—provide additional evidence of families’ perceived need and interest in sibling-focused prevention programming [34]. Targeting the sibling relationship may reduce the stigma involved in prevention programs. Given that problematic sibling dynamics are common in families and a source of stress for parents, parents may be motivated to involve their children in a sibling relationship-oriented program. The Family Nights were centered on parents’ learning about their children’s experiences including in a show-and-tell format. This may have reinforced to parents that it was their children, not themselves, who were in the intervention’s spotlight. In a prior paper [34], we assessed the feasibility of SAS, reporting that parents and school administrators were satisfied with the program and that it could be delivered with fidelity. Parents also rated some program “tools”—strategies for managing sibling conflict and relationships—as being more helpful and more often used than others. Thus, we have a foundation for improving SAS to attain stronger and more consistent benefits for families. The results here, indicating impact on positive but not negative dimensions of sibling relations and child adjustment, also suggest that there is an opportunity to modify and improve SAS. The program’s partial success, however, evidences the promise of incorporating siblings into the prevention repertoire. We envision future development of this and other programs focused on sibling relationships as well as integrating sibling-focused strategies into other family, school, and community based programs.

Implications and Contribution.

This study represents one of the few randomized trials ever conducted to harness the power of sibling relationships to promote youth adjustment. To our knowledge, this is the only sibling-relationship focused prevention trial that has used a universal approach to promote youth adjustment and family relationships in early adolescence.

Table 4.

Siblings Are Special outline

| Session # | Title | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | Building Positive Feelings |

This session introduces the program to the participants, establishes the rules and routines of the program, fosters a positive group environment, and promotes positive sibling interaction. |

| Session 2 | Understanding Feelings |

The Traffic Light is introduced as a tool to help with self-control. Children practice identifying their own and others’ feelings, and are coached in practicing to identify and express their feelings with various levels of intensity. |

| Session 3 | OK and NOT OK | Children learn how to communicate their feelings without blaming or hurting others’ feelings. They also practice how to handle strong feelings such as jealousy and how to use the Traffic Light to calm down in stressful situations. |

| Session 4 | Working together | This session introduces the idea that siblings can work together as a team. Siblings will create a team mascot. Children practice listening carefully and practice self-control using the RED LIGHT to stay calm in an exciting situation. |

| Family Night 1 |

Introduction | Program tools and lessons are shared with parents: Red Light, Compliments, and Building a Team. |

| Session 5 | Ears and Ideas | The session introduces the YELLOW LIGHT, in which children listen carefully to each other, discuss the problem, think of choices together, and make a plan. The focus is on generating ideas for problem solving and listening respectfully to others. |

| Session 6 | Win-Win | This session focuses on the act of negotiating and agreeing on a good idea. Children will learn to look for WIN-WIN ideas and identify differences between WIN-WIN, WIN-LOSE, and LOSE-LOSE ideas. |

| Session 7 | Rejection and Deals | This session helps children explore feeling rejected. They brainstorm win-win solutions to problems with feeling rejected and learn ways to be more inclusive with their sibling. They learn about how to solve problems using negotiation and that making a deal is part of being a team. |

| Session 8 | Fair Play | This session again focuses on siblings as a team, with much time spent on ideas and practices concerning Fair Play. |

| Family Night 2 |

Family Nite 2 | Program tools and lessons: Yellow Light, Talking Stick, Fair Play and Positive Leisure Activity Choices. Parents are also coached on how and when to intervene and help manage sibling conflict. |

| Session 9 | Respect | The group is separated into older sibling sub-group and a younger sibling sub-group in order to discuss the sensitive topic of treating a sibling respectfully. |

| Session 10 |

Goal Setting | This session teaches children how to set goals specific to improving their sibling relationship. Goal setting and planning initially focuses on reducing difficult situations. Children will then consider positive goals. This session also touches appropriate ways to ask for help, giving and receiving social support from family members, and tattling. |

| Session 11 |

Fairness | Children discuss perceptions of fairness in situations that involve parents’ differential treatment of siblings. Children learn ways to problem-solve unfair situations, and are exposed to the idea that some situations feel unfair even when differential treatment is appropriate. |

| Session 12 |

Siblings Are Special | This session focuses on the siblings’ relationship and how much they’ve developed over the past months. The activities in this session aim to show the positive influence they’ve had on each other and illustrate the bonds that they’ve strengthened in their relationship. |

| Family Night 3 |

Family Nite 3 | Program tools and lessons: Decision-making, Respect, Fair Play, and Compliments. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Karen Bierman, Kimberly Updegraff, Lew Bank, and Gene Brody for their collaboration and support in our initial conceptualization of a sibling-focused, universal preventive intervention; Stephen Erath and Kerry Weissman contributed to the initial intervention development and piloting. We also thank the families who participated in the study. Support for this work was provided by a grant from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (DA025035) and funding from Pennsylvania State University’s Children, Youth, and Family Consortium.

References

- 1.Kim J-Y, et al. Longitudinal linkages between sibling relationships and adjustment from middle childhood through adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(4):960–973. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waldinger RJ, E G, Vaillant, Orav EJ. Childhood Sibling Relationships as a Predictor of Major Depression in Adulthood: A 30-Year Prospective Study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:949–954. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shortt JW, et al. Maternal emotion coaching, adolescent anger regulation, and siblings’ externalizing symptoms. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines. 2010;59:799–808. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conger RD, Rueter MA. Siblings, parents, and peers: A longitudinal study of social influences in adolescent risk for alcohol use and abuse. In: Brody GH, editor. Sibling relationships: Their causes and consequences. Advances in applied developmental psychology. Ablex Publishing; Westport, CT, US: 1996. pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rende R, et al. Sibling effects on substance use in adolescence: social contagion and genetic relatedness. Journal of Family Psychology. Special Issue: Sibling Relationship Contributions to Individual and Family Well-Being. 2005;19(4):611–618. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagan AA, Najman JM. The relative contributions of parental and sibling substance use to adolescent tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(4):869–884. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trim RS, Leuthe E, Chassin L. Sibling Influence on Alcohol Use in a Young Adult, High-Risk Sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67(3):391–398. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGue M, Sharma A. Parent and sibling influences on adolescent alcohol use and misuse: Evidence from a U.S. adoption cohort. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;57(1):8–18. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia MM, et al. Destructive sibling conflict and the development of conduct problems in young boys. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(1):44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Snyder J, Bank L, Burraston B. The consequences of antisocial behavior in older male siblings for younger brothers and sisters. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:643–653. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.East PL, Khoo ST. Longitudinal pathways linking family factors and sibling relationship qualities to adolescent substance use and sexual risk behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology. Special Issue: Sibling Relationship Contributions to Individual and Family Well-Being. 2005;19(4):571–580. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rosario-Sim MG, O’Connell KA. Depression and language acculturation correlate with smoking among older Asian American adolescents in New York City. Public Health Nursing. 2009;26(6):532–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2009.00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McHale SM, Crouter AC. The family contexts of children’s sibling relationships. In: Brody GH, editor. Sibling relationships: Their causes and consequences. Advances in applied developmental psychology. Ablex Publishing Corp; Norwood, NJ, USA: 1996. pp. 173–195. 10. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perlman M, Ross H. The benefits of parent intervention in children’s disputes: An examination of concurrent changes in children’s fighting styles. Child Development. 1997;64:690–700. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bank L, et al. Sibling Intervention for Children with Conduct Problems: Testing the Benefits for Older and Younger Siblings. 2011.

- 16.Kramer L. Experimental intervention in sibling relationships. In: Conger RD, Lorenz FO, Wickrama KAS, editors. Continuity and Change in Family Relations. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patterson GR. Siblings: Fellow travelers in the coercive family process. In: Blanchard RJ, Blanchard DC, editors. Advances in the study of aggression. Academic Press; New York: 1984. pp. 235–264. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Natsuaki MN, et al. Aggressive behavior between siblings and the development of externalizing problems: Evidence from a genetically sensitive study. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(4):1009–1018. doi: 10.1037/a0015698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dishion TJ, et al. Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27(1):172–180. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bank L, Patterson GR, Reid JB. Negative sibling interaction patterns as predictors of later adjustment problems in adolescent and young adult males. In: Brody GH, editor. Sibling relationships: Their causes and consequences. Advances in applied developmental psychology. Ablex Publishing; Westport, CT: 1996. pp. 197–229. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bullock BM, Dishion TJ. Sibling collusion and problem behavior in early adolescence: Toward a process model for family mutuality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:143–153. doi: 10.1023/a:1014753232153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bricker JB, et al. Close friends’, parents’, and older siblings’ smoking: Reevaluating their influence on children’s smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8(2):217–226. doi: 10.1080/14622200600576339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyle MH, et al. Familial influences on substance use by adolescents and young adults. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2001;92:206–209. doi: 10.1007/BF03404307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slomkowski C, et al. Sisters, brothers, and delinquency: Evaluating social influence during early and middle adolescence. Child Development. 2001;72:271–283. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milevsky A, Levitt MJ. Sibling support in early adolescence: Buffering and compensation across relationships. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2005;2(3):299–320. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gass K, Jenkins J, Dunn J. Are sibling relationships protective? A longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(2):167–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brody GH. Parental monitoring: Action and reaction. In: Crouter AC, Booth A, editors. Children’s influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ, US: 2003. pp. 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobson KC, Crockett LJ. Parental monitoring and adolescent adjustment: An ecological approach. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10:65–97. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McHale SM, Bissell J, Kim J. Sibling relationship, family, and genetic factors in sibling similarity in sexual risk. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:562–572. doi: 10.1037/a0014982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenberg MT, et al. Promoting emotional competence in school-aged children: The effects of the PATHS curriculum. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:117–136. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bierman KL, Greenberg MT, C.P.P.R. Group . Social skills training in the Fast Track Program. In: Peters RD, McMahon RJ, editors. Preventing childhood disorders, substance abuse, and delinquency. Banff international behavioral science series. Vol. 3. Sage Publications, Inc; Newbury Park, CA: 1996. pp. 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- 32.USCensusBureau . State and County Quick Facts. Pennsylvania: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faber A, Mazlish E. Siblings Without Rivalry. Avon Books; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feinberg ME, et al. Enhancing Sibling Relationships to Prevent Adolescent Problem Behaviors: Theory, Design and Feasibility of Siblings Are Special. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Howe N, Recchia H. Playmates and teachers: reciprocal and complementary interactions between siblings. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19(4):497–502. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stocker C, Ahmed K, Stall M. Family relationships study, parent-child interaction video coding system. University of Denver; Denver: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shebloski B, et al. The Social Interactions Between Siblings Process Codes SIBS-PC. University of California; Davis: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blyth D, Hill J, Thiel K. Early adolescents’ significant others: Grade and gender differences in perceived relationships with familial and nonfamilial adults and young people. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1982;11:425–450. doi: 10.1007/BF01538805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stocker CM, McHale SM. The nature and family correlates of preadolescents’ perceptions of their sibling relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1992;9(2):179–195. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peterson JL, Zill N. Marital disruption, parent-child relationships, and behavioral problems in children. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1986;48:295–307. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Humphrey LL. Children’s and teachers’ perspectives on children’s self-control: The development of two rating scales. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1982;50(5):624–633. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.5.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stormshak EA, et al. The quality of sibling relationships and the development of social competence and behavioral control in aggressive children. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:79–89. [Google Scholar]

- 43.DuPaul GJ, Rapport MD, Perriello LM. Teacher ratings of academic skills: The development of the Academic Performance Rating Scale. School Psychology Review. 1991;20:284–300. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McHale SM, et al. Step in or stay out? Parents’ roles in adolescent siblings’ relationships. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62(3):746–760. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]