Abstract

Background

Previous research has implicated the behavioral activation system (BAS) in depression. The relation of BAS functioning to aspects of cognitive vulnerability to depression, however, is not known.

Methods

The present study investigated associations among level of BAS functioning and the encoding and recall of positive and negative self-referent information in currently nondepressed participants with a history of recurrent major depression (recovered; RMD) and in never-depressed control participants (CTL). Participants completed self-report measures of levels of BAS and behavioral inhibition system (BIS) functioning. Following a negative mood induction, participants were presented with a series of positive and negative adjectives; they indicated which words described them and later recalled as many of the words as they were able.

Results

The relation of BAS functioning to self-referent processing was dependent on participant group. Although lower BAS reward responsivity was associated with the endorsement and recall of fewer positive words across groups, the magnitude of these associations was stronger, and was only significant, within the RMD group. Furthermore, only for RMD participants was lower BAS reward responsivity associated with the endorsement of more negative words. These effects were not accounted for by depressive or anxiety symptoms, current mood, or level of BIS functioning.

Conclusions

These results indicate that BAS functioning may be distinctively linked to negatively biased self-referent processing, one facet of cognitive vulnerability to depression, in individuals with a history of MDD. Enhancing BAS functioning may be important in buffering cognitive vulnerability to depression.

Keywords: depression, behavioral activation system, remission, cognitive processing, memory

Depressed mood and loss of interest or pleasure are hallmark symptoms of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Biopsychological models of emotion postulate a behavioral activation system (BAS) that regulates reward sensitivity and behavioral approach (e.g., Fowles, 1988; Depue & Iacono, 1989; Gray, 1994), which, when underactive, manifests as the diminished positive affect and goal motivation that characterizes MDD (e.g., Davidson, 1992; Mineka et al. 1998). These models also postulate a behavioral inhibition system (BIS) that regulates sensitivity to threat and behavioral avoidance; higher levels of BIS functioning have been associated with both depression and anxiety disorders (see Zinbarg & Yoon, 2008; and Bijttebier et al. 2009, for reviews of this literature).

Investigators have reliably documented a relation between diminished BAS functioning and unipolar depression (e.g., Henriques et al. 1994; Harmon-Jones & Allen, 1997). Based on Davidson’s (1992) proposal that electrophysiological activity in the left hemisphere is positively associated with BAS functioning, researchers have used electroencephalography (EEG) to demonstrate that depressed individuals are characterized by left relative to right frontal hypoactivation (e.g., Henriques & Davidson, 1991; Gotlib et al.1998). Carver and White (1994) developed the commonly used self-report BIS/BAS scales, in which the BIS scale measures sensitivity to experiencing fear and anxiety in response to imminent punishment, and the BAS scales measure sensitivity to experiencing positive emotions such as happiness, excitement, and hope in response to imminent reward. Researchers using these measures have found that depressed individuals report lower levels of BAS functioning than do nondepressed controls (e.g., Kasch et al. 2002), and that in unselected samples, lower levels of BAS functioning are associated with more severe depressive symptoms (e.g., Beevers & Meyer, 2002; Spielberg et al. 2011). Importantly, individuals who have recovered from depression have been found to exhibit the same patterns of frontal cortical asymmetry (Henriques & Davidson, 1990; Gotlib et al. 1998; reviewed in Thibodeau et al. 2006) and self-reported levels of BAS functioning (Pinto-Meza et al. 2006) that have been documented in depressed individuals. Furthermore, in a recent study of individuals with no history of depression, Nusslock et al. (2011) found that left frontal hypoactivation predicted the subsequent onset of a first depressive episode, suggesting that reductions in BAS sensitivity are not simply a consequence or scar of previous depressive episodes. In sum, the results of cross-sectional and longitudinal research converge on the formulation that BAS functioning is related to vulnerability to depression (Carver & White, 1994; Gray, 1994; Campbell-Sills et al. 2004).

Carver and White’s (1994) BAS scale is composed of three subscales: BAS-Reward Responsiveness (BAS-RR), BAS-Drive, and BAS-Fun-Seeking (BAS-Fun) (e.g., Huebeck et al. 1998; Jorm et al. 1999; Ross et al. 2002; Campbell-Sills et al. 2004; Levinson et al. 2011). BAS-RR measures affective responding, BAS-Drive assesses behavioral responding, and BAS-Fun measures affective and behavioral responding (Carver & White, 1994; Campbell-Sills et al. 2004). Interestingly, within samples diagnosed with MDD, BAS-RR most consistently predicts the general course of the disorder, whereas BAS-Drive predicts specific aspects of disorder course. For example, Kasch and colleagues (2002) found that in participants with MDD, lower BAS-RR and BAS-Drive scores predicted the subsequent persistence of the diagnosis and a higher number of depressive symptoms at an eight-month follow-up assessment; lower baseline BAS-RR scores also predicted greater severity of depressive symptoms. Similarly, McFarland and colleagues (2006) found that after controlling for baseline clinical variables, lower BAS-RR and BAS-Drive scores predicted the maintenance of MDD at a six-month follow-up assessment; lower BAS-RR scores also predicted a higher number of subsequent depressive symptoms and poorer psychiatric status. These findings indicate that, even within depressed groups, variation in BAS functioning may be a marker for disorder persistence and subsequent symptomatology. Indeed, BAS sensitivity may be a particularly potent risk factor for depression in persons who are already vulnerable to MDD because of having experienced prior episodes.

The precise mechanisms explaining the association between reductions in BAS functioning and risk for depression are not yet known. Theorists have proposed that because persons with diminished BAS sensitivity are less responsive to positive stimuli, they have a lower likelihood of exerting effort toward or engaging in potentially rewarding experiences, which thereby increases their risk for depression (e.g., Depue & Iacono, 1989; Fritzsche et al. 2010). It is also possible that BAS functioning is related to aspects of cognitive vulnerability to depression. Spurred by Beck’s (1967) concept of negative cognitive schemas as risk factors for depression, a large body of research has demonstrated that depression is associated with negative biases in the processing of self-referent information, as one such facet of cognitive vulnerability (reviewed in Beevers, 2005, and Gotlib & Joormann, 2010).

In this context, investigators have used the self-referential encoding task (SRET; Derry & Kuiper, 1981), an information-processing task that assesses self-schema function, to examine the processing of valenced stimuli in depressed, recovered depressed, and nondepressed participants. Depressed individuals have been shown to endorse and recall more negative and/or less positive self-referent information than do their nondepressed counterparts. Findings for persons who have recovered from MDD are less consistent; an initial negative mood induction appears necessary to detect negatively biased self-referent processing in this group (e.g., Dobson & Shaw, 1987; Fritzsche et al. 2010).

Researchers have recently begun to explore the relations between BAS functioning and different facets of cognitive vulnerability to depression, although they have not yet examined self-referent processing. Beevers and Meyer (2002) found in an unselected sample of participants that positive experiences and expectancies mediated the relation between self-reported level of BAS functioning and anhedonic symptoms of depression. Similarly, Nusslock et al. (2011) found that left frontal hypoactivation in their sample of currently nondepressed participants was associated with the extent to which the participants attributed negative events to stable and global causes and endorsed likely negative consequences of the events.

The present study is the first to examine associations among BAS functioning and one aspect of cognitive vulnerability to depression in both a clinical sample (participants with a history of recurrent major depression [RMD]) and in never-depressed control (CTL) participants. As we noted above, BAS sensitivity has been found to be related to risk for depression in both clinical and non-clinical samples; therefore, we hypothesized that lower self-reported level of BAS functioning would be associated with less positive and more negative self-referent processing across both groups. Given the particularly striking relation of BAS sensitivity to risk for future depression within samples of individuals who are already vulnerable to MDD, however, we hypothesized that these associations between BAS functioning and self-referent processing would be stronger in the RMD group than in the CTL group. In the present study we focused on level of BAS-RR because it is the BAS subscale that has been found most consistently to predict depression course. To assess the specificity and robustness of the association of BAS-RR with self-referent processing, we controlled for current levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms (e.g., Kasch et al. 2002) and also assessed the relation between BIS functioning and self-referent processing.

Method

Participants

Participants were 152 women (70 RMD and 82 CTL) between the ages of 18 and 60 years who were fluent in English. Participants were recruited through advertisements and online postings, and were screened for initial inclusion/exclusion through a telephone interview. Exclusion criteria included: history of severe head trauma; learning disabilities; bipolar disorder; psychotic symptoms; and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) alcohol or substance abuse within the past six months. The phone interview identified participants who were likely to meet criteria for inclusion in one of the two study groups: (a) individuals with a history of two or more major depressive episodes who did not meet DSM-IV criteria for current MDD (RMD); and (b) individuals with no past or current DSM-IV Axis I disorder (CTL). These individuals were invited to participate in an interview in the laboratory using the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID; Spitzer et al. 1996), conducted by a trained interviewer. Inter-rater reliability is excellent among our laboratory interviewers, both for classifying a major depressive episode (k=.93) and for classifying control participants (k=.92; Levens & Gotlib, 2010).

Self-Report Measures

Participants completed several self-report questionnaires, including the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al. 1996), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck et al. 1988), and BIS/BAS scales (Carver & White, 1994). As we noted above, the 20-item BIS/BAS assesses how individuals typically react to situations across four subscales. Sample subscale items include: “If I think something unpleasant is going to happen, I usually get pretty ‘worked up’” (BIS); “When I’m doing well at something, I love to keep at it” (BAS-RR); “I go out of my way to get things I want” (BAS-Drive); and “I’m always willing to try something new if I think it will be fun” (BAS-Fun). Participants rate each item on a four-point Likert scale (1=very true for me, 4=very false for me). In the current study, internal consistencies of the subscales were moderate to high (BIS=.79; BAS-RR=.62; BAS-Drive=.79; BAS-Fun=.63); intercorrelations among the BAS subscales were moderate (rs=.48–.50). None of the BAS subscales was correlated significantly with the BIS subscale.

Procedure

Participants completed the phone interview and the SCID; immediately following the SCID, participants completed the self-report questionnaires. A second laboratory session was scheduled within one week. During this session, participants completed a baseline mood assessment in which they rated their current mood on a 5-point Likert Scale (1=very sad, 5=very happy). Immediately before completing the self-referential encoding task (SRET), participants underwent a negative mood induction (see below) and subsequently completed a mood assessment in the same manner as at baseline. Participants then completed the SRET. The SRET was one of three counterbalanced tasks completed by participants in the session. The results for BAS-RR presented below did not change when including task order as a predictor.

Mood Induction

Previous research has found that cognitive biases are present after recovery from a depressive episode, but may remain dormant or latent until activated by a negative mood (see Scher et al. 2005, for a review). Therefore, we induced a negative mood in all participants before they completed the SRET. Participants were randomly assigned to view one of three six-minute sadness-inducing film clips (Dead Poets Society, Weir, 1989; My Girl, Zieff, 1991; Stepmom, Columbus, 1998). Participants were instructed to “imagine being in the situation” and “imagine the feelings you would experience in the situation” while viewing it, an instructional set demonstrated to be highly effective in inducing negative mood (Westermann et al. 1996). Following the film clip, participants were instructed to think for an additional two minutes about how they would feel if they had experienced the situation. The results for BAS-RR presented below did not change when including film clip as a predictor.

Self-Referential Encoding Task (SRET)

The SRET was composed of a set of 40 adjectives: 20 positive (e.g., happy, interesting, smart); and 20 negative (e.g., boring, lazy, stupid). Adjectives were selected from several sources, including previous studies of information processing in depression (e.g., Gotlib & Cane, 1987; McCabe & Gotlib, 1993). A larger set of adjectives was rated on positive and negative valence by five psychology graduate students; adjectives were retained for the final set only if agreement was unanimous. The positive and negative word lists did not differ in word length, familiarity, or level of arousal (all ps>.05).

Participants were seated in front of a computer and were instructed to place their right index finger on a key labeled ‘yes’ and their left index finger on a key labeled ‘no’. For each trial, participants were presented with the phrase ‘Describes me?’ in the middle of the screen for 500 ms. After a pause of 250 ms, participants were presented with one of the stimulus words in random order and were instructed to indicate as quickly and accurately as possible whether the word described them by pressing the corresponding key. Participants’ responses were recorded on each trial. A fixation cross was presented for 1000 ms during each inter-trial interval. Participants first completed a series of practice trials, followed by the experimental trials during which the experimenter waited outside of the room.

After the encoding task, the experimenter returned to the room to administer an incidental recall task. The experimenter provided a sheet of paper to participants and asked them to recall as many words as possible from the previous task, regardless of whether or not they had endorsed the words as self-descriptive. The task did not have a time limit. Participants were instructed to notify the experimenter when they were done.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics for the RMD and CTL groups are presented in Table 1. The groups did not differ in age, t(134.37)=.52, ns, proportion of college-educated participants, χ2(1,N=151)=1.62, ns, or distribution by race/ethnicity, χ2(5,N=150)=3.83, ns. RMD participants were more likely than were CTL participants to be taking psychotropic medication, χ2(1,N=152)=33.63, p<.001. The results for BAS-RR presented below did not change when including the presence of psychotropic medication as a predictor. RMD participants obtained significantly higher scores than did CTL participants on the BDI-II, t(91.02)=6.87, p<.001. Because of the subsyndromal level of depressive symptoms reported by some participants, we controlled for BDI-II scores in our statistical analyses. As indicated below, results for one analysis became more significant when removing BDI-II score as a predictor or when removing participants with BDI-II scores of 14 (mild depressive symptoms) or higher. RMD participants also obtained significantly higher scores than did CTL participants on the BAI, t(98.44)=6.04, p<.001. Thirteen RMD participants had a current DSM-IV anxiety disorder: three had social phobia; two had specific phobia; two had obsessive-compulsive disorder; two had posttraumatic stress disorder; four had generalized anxiety disorder; and one had anxiety disorder not otherwise specified. The results for BAS-RR did not change when removing BAI score as a predictor or when removing participants with current anxiety disorders. Finally, RMD participants obtained significantly higher scores on the BIS subscale, t(150)=4.39, p<.001, and significantly lower scores on the BAS-Drive subscale, t(150)=−3.05, p<.005, than did CTL participants; the groups did not differ in scores on the BAS-RR, t(150)=0.91, ns, or BAS-Fun, t(150)=1.18, ns, subscales.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the RMD and CTL Groups

| Variable | RMD

|

CTL

|

|---|---|---|

| M (SD) or % | M (SD) or % | |

|

|

|

|

| Age | 43.74 (6.15) | 44.22 (5.10) |

| % college educated | 78.57% | 86.42% |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 78.57% | 73.17% |

| Hispanic | 7.14% | 4.87% |

| African American | 2.86% | 3.65% |

| Asian American | 5.71% | 12.20% |

| Native American | 1.43% | 0.00% |

| Other | 2.86% | 4.87% |

| % taking psychotropic medication | 40.00% | 2.44% |

| BDI-II score | 12.41 (9.97) | 3.48 (4.37) |

| BAI score | 8.60 (6.52) | 3.40 (3.30) |

| BIS score | 22.86 (3.63) | 20.48 (3.05) |

| BAS-RR score | 16.59 (1.96) | 16.88 (1.98) |

| BAS-Drive score | 10.53 (2.23) | 10.94 (2.06) |

| BAS-Fun score | 9.67 (2.59) | 10.87 (2.24) |

Note. RMD=currently nondepressed participants with a history of recurrent major depression; CTL=never-depressed control participants; M=mean; SD=standard deviation; BDI-II=Beck Depression Inventory-II; BAI=Beck Anxiety Inventory; BIS=Behavioral Inhibition subscale; BAS=Behavioral Activation subscale; BAS-RR=BAS Reward Responsiveness; BAS-Fun=BAS Fun-Seeking. Education data were missing for one CTL participant, and race/ethnicity data were missing for 1 CTL participant and 1 RMD participant. BDI-II data were missing for five CTL participants and one RMD participant.

Due to missing data the percentages do not sum to 100%.

Mood Induction

Self-reported mood data were missing for one CTL participant and two RMD participants. To examine the effectiveness of the mood induction, a Group (CTL, RMD) x Time (baseline, after mood induction) repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on self-reported mood. As expected, this analysis yielded a main effect of time, F(1,147)=424.58, p<.001: participants reported more negative mood after the induction than before the induction. The analysis also yielded a main effect of group, F(1,147)=5.39, p<.05: RMD participants reported more negative mood than did CTL participants. The interaction of group and time was not significant, F(1,147)=1.14, ns. Given these findings, in all subsequent analyses we controlled for self-reported mood.

SRET

Descriptive statistics for the SRET variables are presented in Table 2. Correlations among BIS/BAS scores and SRET variables, BDI-II scores, and BAI scores within the RMD and CTL groups are presented in Table 3. There were two outliers for SRET negative words endorsed (>3 SD from mean). The results for BAS-RR below did not change with these values winsorized. Hierarchical regression analyses (Cohen & Cohen, 1983) were conducted to test the unique associations of group, BIS and BAS-RR, and the interactions of group with BIS and BAS-RR with each of the SRET variables, controlling for the effects of BDI-II and BAI scores and self-reported mood. Each SRET variable was modeled separately. To first assess group differences in self-referent processing, group (b1), BDI-II score (b2), BAI score (b3), and self-reported mood (b4) were entered in Model 1. Next, BIS level (b5) and BAS-RR level (b6) were entered in Model 2. Finally, the interactions of group with BIS level (b7) and with BAS-RR level (b8) were entered in Model 3. The CTL group was coded as 0, and the RMD group was coded as 1; all other variables were centered at their respective grand means.

Table 2.

SRET Performance by the RMD and CTL Groups

| SRET Variable | RMD

|

CTL

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | range | M (SD) | range | |

|

|

|

|

||

| Number of positive words endorsed | 13.50 (4.39) | 4–20 | 16.72 (3.07) | 5–20 |

| Number of negative words endorsed | 5.99 (3.60) | 1–17 | 2.43 (2.81) | 0–20 |

| Proportion of positive words endorsed and recalled | .73 (.17) | .38–1.00 | .88 (.12) | .56–1.00 |

| Proportion of negative words endorsed and recalled | .27 (.17) | .00–.63 | .12 (.12) | .00–.44 |

Note. RMD=currently nondepressed participants with a history of recurrent major depression; CTL=never-depressed control participants; M=mean; SD=standard deviation; SRET=Self-Referential Encoding Task.

Table 3.

Correlations among Variables within the RMD and CTL Groups

| Variable | RMD

|

CTL

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIS | BAS-RR | BAS-Drive | BAS-Fun | BIS | BAS-RR | BAS-Drive | BAS-Fun | |

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Number of positive words endorsed | −.26* | .50** | .59** | .32* | −.21 | .09 | .23* | .17 |

| Number of negative words endorsed | .33* | −.29* | −.09 | −.12 | .26* | .14 | .01 | .05 |

| Prop. of positive words endorsed and recalleda | −.20 | .29* | .26* | .19 | −.14 | .05 | .07 | .07 |

| BDI-II score | .14 | −.04 | −.15 | −.13 | .00 | .05 | .06 | .13 |

| BAI score | .00 | .11 | .04 | .06 | .31** | −.02 | −.16 | −.11 |

Note. RMD=currently nondepressed participants with a history of recurrent major depression; CTL=never-depressed control participants; BIS=Behavioral Inhibition subscale; BAS=Behavioral Activation subscale; BAS-RR=BAS Reward Responsiveness; BAS-Fun=BAS Fun-Seeking; BDI-II=Beck Depression Inventory-II; BAI=Beck Anxiety Inventory.

p<.05 for correlation,

p<.01 for correlation.

Correlations with proportion of negative words endorsed and recalled are identical with the opposite sign.

Group Differences

Controlling for BDI-II and BAI scores and self-reported mood, RMD participants endorsed significantly fewer positive words, b1=−.22, t(138)= −2.60, p=.01, and significantly more negative words, b1=.25, t(138)=3.29, p=.001, than did CTL participants. Consistent with the recall analyses reported in previous research (e.g., Fritzche et al. 2010), to control for individual differences in overall endorsement and recall we computed recall of endorsed positive and negative words as proportions of the total number of words endorsed and recalled. Because these proportions sum to 1, and analyses of positive and negative words produce identical coefficients with the opposite sign, we present recall results only for positive words. Controlling for BDI-II and BAI scores and self-reported mood, RMD participants exhibited poorer recall of endorsed positive words than did CTL participants, b1=−.21, t(138)= −2.65, p<.01.

Main Effects of BIS and BAS-RR

Across groups, higher BIS scores were associated with endorsement of fewer positive words, b5=−.27, t(136)= −3.90, p<.001, and more negative words, b5=.24, t(136)=3.67, p<.001, and with poorer recall of endorsed positive words, b5=−.14, t(136)= −2.03, p<.05. Across groups, lower BAS-RR scores were associated with endorsement of fewer positive words, b6=.31, t(136)=4.70, p<.001, and with poorer recall of endorsed positive words, b6=.19, t(136)=2.95, p<.005.

Interactions of Group with BIS and BAS-RR

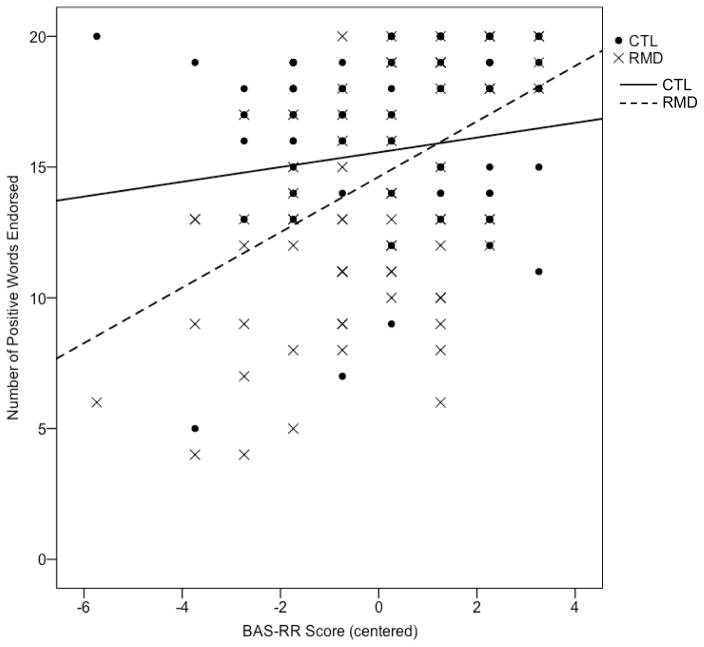

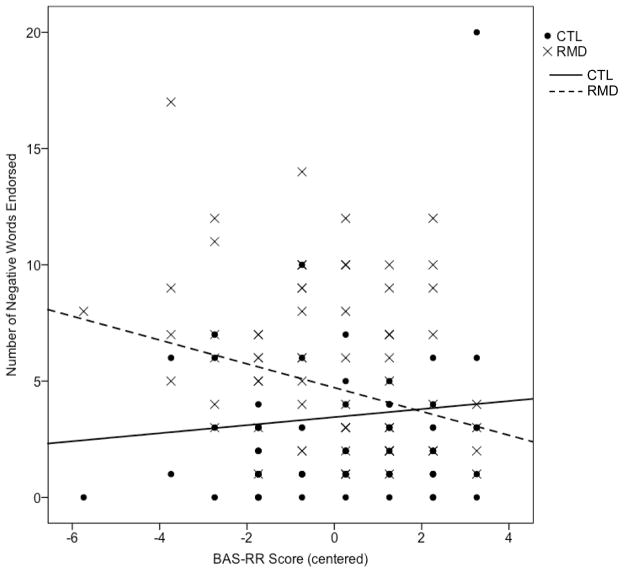

There were no group differences in the association of BIS scores with endorsement of positive, b7=.09, t(134)=0.94, ns, or negative, b7=.05, t(134)=0.48, ns, words, or recall of endorsed positive words, b7=−.05, t(134)= −0.52, ns. There was a significant group difference in the association of BAS-RR scores with endorsement of positive words, b8=.26, t(134)=2.94, p<.005. Tests of the simple slopes indicated that for RMD participants, lower BAS-RR scores were significantly associated with fewer positive words endorsed, t(134)=5.56, p<.001, 95% CI for β [.68, 1.44], whereas for CTL participants, BAS-RR scores were unrelated to endorsement of positive words, t(134)=1.54, ns, 95% CI for β [−.08, .64] (Figure 1). There was also a significant group difference in the association of BAS-RR scores with endorsement of negative words, b8=−.25, t(134)= −3.01, p<.005. Tests of the simple slopes indicated that for RMD participants, lower BAS-RR scores were associated with more negative words endorsed, t(134)= −3.12, p<.005, 95% CI for β [−.84, −.19], whereas for CTL participants, this association was not significant and, indeed, was in the opposite direction, t(134)=1.10, ns, 95% CI for β [−.14, .48] (Figure 2). Finally, there was a marginally significant group difference in the association of BAS-RR scores with recall of endorsed positive words, b8=.17, t(134)=1.91, p=.06. Tests of the simple slopes indicated that for RMD participants, lower BAS-RR scores were significantly associated with poorer recall of endorsed positive words, t(134)=3.41, p=.001, 95% CI for β [.01, .04], whereas for CTL participants, BAS-RR scores were unrelated to recall of endorsed positive words, t(134)=0.79, ns, 95% CI for β [−.01, .02]. The interaction term was significant when BDI-II score was removed as a predictor, b7=.20, t(141)=2.16, p<.05, and when participants with BDI-II scores of 14 (mild depressive symptoms) or higher were removed, b8=.23, t(106)=2.14, p<.05.

Figure 1.

Association between BAS-RR score and number of positive words endorsed within the RMD and CTL groups. Note. RMD=currently nondepressed participants with a history of recurrent major depression; CTL=never-depressed control participants. Group reference lines were computed using unstandardized coefficients from the hierarchical regression.

Figure 2.

Association between BAS-RR score and number of negative words endorsed within the RMD and CTL groups. Note. RMD=currently nondepressed participants with a history of recurrent major depression; CTL=never-depressed control participants. Group reference lines were computed using unstandardized coefficients from the hierarchical regression.

To ensure the specificity of association between BAS-RR functioning and self-referent processing, we also tested the unique associations of the interactions of group with BAS-Drive and BAS-Fun with each of the SRET variables, controlling for the effects of BDI-II and BAI scores and self-reported mood. Only one interaction was significant: across groups, higher BAS-Drive scores were associated with endorsement of more positive words, b=.38, t(137)=5.74, p<.001, and there was a significant group difference in the association of BAS-Drive scores with endorsement of positive words, b=.24, t(136)=2.55, p=.01. Tests of the simple slopes indicated that for RMD participants, lower BAS-RR scores were significantly associated with fewer positive words endorsed, t(136)=5.98, p<.001, 95% CI for β [.58, 1.16], and for CTL participants, this association was less strong but still significant, t(136)=2.11, p<.05, 95% CI for β[.02, .63].

Discussion

This is the first study to examine associations among BIS/BAS functioning and cognitive processing in individuals at high risk for MDD by virtue of having experienced previous recurrent depressive episodes. Replicating Fritzsche et al.’s (2010) findings, RMD participants endorsed and recalled fewer positive and more negative self-referent adjectives than did CTL participants. It is notable that these group differences remained even after controlling for depressive and anxiety symptoms and current mood. With respect to BAS functioning, lower BAS-RR level was associated with the endorsement and recall of fewer positive words across the full study sample. Importantly, however, we found that group and BAS-RR interacted in their relations with self-referent processing such that self-reported level of BAS-RR functioning was more strongly associated with self-referent processing for RMD participants than it was for CTL participants. Indeed, only in the RMD group was lower BAS-RR level related to endorsement of more positive and fewer negative self-referent words and with poorer recall of endorsed positive words. Below we discuss the potential implications of these findings.

These results expand findings of previous studies relating diminished BAS sensitivity to a poorer course of depression (e.g., Kasch et al. 2002; McFarland et al. 2006), and add to a growing literature integrating BIS/BAS functioning and cognitive risk for depression (Beevers & Meyer, 2002; Nusslock et al. 2011). Theorists have suggested that low BAS sensitivity increases risk for depression through behavioral mechanisms such as low levels of engagement in potentially rewarding activities (e.g., Depue & Iacono, 1989). Interestingly, Abramson et al. (2002) conceptualize deficiencies in BAS functioning as a reflection of hopelessness, which arises from negative perceptions and assumptions, including those about the self. In demonstrating distinctive relations of low BAS affective responsivity to more negatively biased self-perceptions and memory biases in persons vulnerable to depression, the present findings generally support this notion. Furthermore, these findings suggest that, rather than being associated in a uniform fashion across the population, BAS functioning and cognitive processing are more rigidly interconnected in individuals with a history of recurrent depression. In fact, such rigid interrelations between affective and cognitive functioning, in contrast to a more flexible system of responding, may underlie a proneness to repeatedly experience depressive episodes, especially in response to stressors. By focusing on self-referent cognitive processing, these findings extend Nusslock et al.’s (2011) results linking BAS functioning with inferences about hypothetical negative events. It will be important for future studies to investigate associations among BAS functioning and cognitive processing in response to laboratory and real-world stressors.

We found in this study that higher level of BAS-RR functioning in RMD participants was associated with the endorsement and recall of more positive words and fewer negative words. These findings suggest that higher levels of affective responding to reward incentives may serve as a buffer against the development of negative self-schemas in individuals at high risk for experiencing further episodes of depression. Building on Beevers and Meyer’s (2002) formulation, it is possible that stronger reward sensitivity motivates individuals to engage in more pleasurable or more frequent mastery experiences that boost their positive self-schemas and reduce their susceptibility to the effects of negative self-schemas. It is also possible that self-relevant cognitions mediate or moderate the effort exerted toward positive experiences. In future research, investigators should address these different directions of effects by examining explicitly the temporal relations among the cognitive and behavioral expressions of reward responsivity. In addition, investigators should also examine the extent to which motivational and cognitive factors, alone and in their interaction, predict the course and recurrence of MDD.

It is noteworthy that BAS-RR functioning had different effects in the recovered and control participants despite the fact that the two groups of participants did not differ in their mean level of BAS-RR. Thus, investigators who compare high-risk and control groups on BIS/BAS and cognitive processing should examine differential correlations as well as group differences in average levels of functioning. Importantly, however, the recovered and never-depressed participants generally did not differ in their associations between BAS-Drive, BAS-Fun, or BIS and self-referent processing. In the one analysis in which the two groups did differ, BAS-Drive was significantly associated with the endorsement of positive words in both groups, but this association was stronger in the RMD than in the CTL group. Given that BDI-II scores were slightly negatively correlated with BAS-Drive and BAS-Fun scores in RMD participants, it is possible that these measures were sources of shared variance in the regression analyses. BAS-RR scores, on the other hand, were unrelated to BDI-II scores and thus captured an aspect of functioning that was statistically independent of depressive symptoms. With respect to BIS functioning, for both RMD and CTL participants higher BIS level was associated with the endorsement of fewer positive and more negative words, suggesting that avoidance motivation is related more generally to less positive and more negative self-referent processing. Given the relevance of BIS to anxiety disorders (reviewed in Zinbarg & Yoon, 2008, and Bijttebier et al. 2009), investigators should continue to examine the relation between BIS and cognitive processing in anxiety disorders.

We should note four limitations of the present study. First, our use of a recovered depressed sample did not allow us to assess whether BAS functioning is related to cognitive biases prior to the initial onset of depression. Thus, it is possible that these observed associations stem from a scar model rather than a broader risk model of depression (Just et al. 2001). Second, as evidenced by our BDI-II data, some participants were reporting depressive symptoms, albeit below the syndromal threshold, at the time of study participation. We controlled for symptom severity statistically, and findings for BAS-RR held when removing these control variables and when removing participants with BDI-II scores at or above the cut-off for mild symptoms. Nevertheless, it is important that investigators examine these hypothesized relations in other samples unaffected by previous depressive episodes. Third, because we did not include a group of currently depressed participants, we do not know whether BAS also moderates information processing during a major depressive episode. Finally, we used the SRET in this study and assessed self-referent processing only following a negative mood induction. Investigators have used a range of cognitive tasks to study information processing in emotional disorders, and it will be important in future studies of clinical samples to examine whether BIS/BAS functioning influences aspects of cognitive functioning other than self-referent processing. In addition, our use of a negative mood induction may enhance the relevance of our findings to theoretical models that emphasize the role of stressors in eliciting cognitive biases (i.e., Abramson et al. 2002). Although the use of negative mood inductions is common in depression-related research (see Scher et al. 2005, for a review), future studies should assess whether these RMD-specific effects also occur in the absence of such an induction.

In sum, the present results suggest that BAS functioning is uniquely associated with cognitive vulnerability to depression in individuals at high risk for MDD by virtue of having experienced prior depressive episodes. Although BAS is presumed to reflect a trait-like risk factor for depression, it clearly interacts with other factors, such as cognitive and behavioral responding, in contributing to the onset of a depressive episode. The assessment of BAS sensitivity may help to identify individuals who could benefit from prevention or intervention efforts focused on enhancing positive cognitions, motivation, and engagement.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grants MH74849 to Ian H. Gotlib and MH096385 to Katharina Kircanski.

References

- Abramson LY, Alloy LB, Hankin BL, Haeffel GJ, MacCoon DG, Gibb BE. Cognitive vulnerability-stress models of depression in a self-regulatory and psychobiological context. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of Depression. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2002. pp. 268–294. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Depression: Clinical, Experimental, and Theoretical Aspects. Hoeber Medical Division; New York: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56:893–897. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory. 2. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG. Cognitive vulnerability to depression: A dual process model. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:975–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beevers CG, Meyer B. Lack of positive experiences and positive expectancies mediate the relationship between BAS responsiveness and depression. Cognition & Emotion. 2002;16:549–564. [Google Scholar]

- Bijttebier P, Beck I, Claes L, Vandereycken W. Gray’s reinforcement sensitivity theory as a framework for research on personality-psychopathology associations. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:421–430. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Liverant GL, Brown TA. Psychometric evaluation of the behavioral inhibition/behavioral activation scale in a large sample of outpatients with anxiety and mood disorders. Psychological Assessment. 2004;16:244–254. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: The BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2. Erlbaum; Hillsdale: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ. Emotion and affective style: Hemispheric substrates. Psychological Science. 1992;3:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Depue RA, Iacono WG. Neurobehavioral aspects of affective disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 1989;40:457–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.40.020189.002325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derry PA, Kuiper NA. Schematic processing and self reference in clinical depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1981;90:286–297. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.90.4.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diego MA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M. BIS/BAS scores are correlated with frontal EEG asymmetry in intrusive and withdrawn depressed mothers. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2001;22:665–675. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson KS, Shaw BF. Specificity and stability of self-referent encoding in clinical depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1987;96:34–40. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders-Clinician Version (SCID-CV) American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC. Psychophysiology and psychopathology: A motivational approach. Psychophysiology. 1988;25:373–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1988.tb01873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsche A, Dahme B, Gotlib IH, Joormann J, Magnussen H, Watz H, Nutzinger DO, von Leupoldt A. Specificity of cognitive biases in patients with current depression and remitted depression and in patients with asthma. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:815–826. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709990948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Cane DB. Construct accessibility and clinical depression: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1987;96:199–204. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Krasnoperova E, Yue DN, Joormann J. Attentional biases for negative interpersonal stimuli in clinical depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:121–135. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Joormann J. Cognition and depression: Current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:285–312. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Ranganath C, Rosenfeld JP. Frontal EEG alpha asymmetry, depression, and cognitive functioning. Cognition and Emotion. 1998;12:449–478. [Google Scholar]

- Gray JA. Framework for a taxonomy of psychiatric disorder. In: van Goozen SHM, van de Poll NE, Sergeant J, editors. Emotions: Essays on Emotion Theory. Erlbaum; Hillsdale: 1994. pp. 29–59. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon-Jones E, Allen JJ. Behavioral activation sensitivity and resting frontal EEG asymmetry: Covariation of putative indicators related to risk for mood disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:159–163. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques JB, Davidson R. Regional brain electrical asymmetries discriminate between previously depressed and healthy control subjects. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99:22–31. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques JB, Davidson RJ. Left frontal hypoactivation in depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:535–545. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques JB, Glowacki JM, Davidson RJ. Reward fails to alter response bias in depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1994;103:460–466. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.103.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heubeck BG, Wilkinson RB, Cologon J. A second look at Carver and White’s (1994) BIS/BAS scales. Personality and Individual Differences. 1998;25:785–800. [Google Scholar]

- Jorm A, Christensen H, Henderson A, Jacomb P, Korten A, Rodgers B. Using the BIS/BAS scales to measure behavioural inhibition and behavioural activation: Factor structure, validity and norms in a large community sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 1998;26:49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Just N, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. Remitted depression studies as tests of the cognitive vulnerability hypotheses of depression onset: A critique and conceptual analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21:63–83. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasch KL, Rottenberg J, Arnow BA, Gotlib IH. Behavioral activation and inhibition systems and the severity and course of depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:589–597. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levens SM, Gotlib IH. Updating positive and negative stimuli in working memory in depression. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2010;139:654–664. doi: 10.1037/a0020283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SB, Gotlib IH. Attentional processing in clinically depressed subjects: A longitudinal investigation. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1993;17:359–377. [Google Scholar]

- McFarland BR, Shankman SA, Tenke CE, Bruder GE, Klein DN. Behavioral activation system deficits predict the six-month course of depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;91:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S, Watson D, Clark LA. Comorbidity of anxiety and unipolar mood disorders. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:377–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nusslock R, Shackman AJ, Harmon-Jones E, Alloy LB, Coan JA, Abramson LY. Cognitive vulnerability and frontal brain asymmetry: Common predictors of first prospective depressive episode. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:497–503. doi: 10.1037/a0022940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto-Meza A, Caseras X, Soler J, Puigdemont D, Pérez V, Torrubia R. Behavioural inhibition and behavioural activation systems in current and recovered major depression participants. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40:215–226. [Google Scholar]

- Ross SR, Millis SR, Bonebright TL, Bailley SE. Confirmatory factor analysis of the behavioral inhibition and activation scales. Personality and Individual Differences. 2002;33:861–865. [Google Scholar]

- Scher CD, Ingram RE, Segal ZV. Cognitive reactivity and vulnerability: Empirical evaluation of construct activation and cognitive diatheses in unipolar depression. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:487–510. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberg JM, Heller W, Silton RL, Stewart JL, Miller GA. Approach and avoidance profiles distinguish dimensions of anxiety and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2011;35:359–371. [Google Scholar]

- Thibodeau R, Jorgensen RS, Kim S. Depression, anxiety, and resting frontal EEG asymmetry: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:715–729. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann R, Spies K, Stahl G, Hesse FW. Relative effectiveness and validity of mood induction procedures: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Social Psychology. 1996;26:557–580. [Google Scholar]

- Zinbarg RE, Yoon KL. RST and clinical disorders: Anxiety and depression. In: Corr PJ, editor. The Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory of Personality. Cambridge University Press; London: 2008. pp. 360–397. [Google Scholar]