Abstract

Purpose

Spiritual coping is an important determinant of adjustment in youth with chronic illness, but the mechanisms through which it affects outcomes have not been elucidated. It is also unknown whether the role of spiritual coping varies by age or disease group. This study evaluated whether general cognitive attributions explain the effects of spiritual coping on internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescents with cystic fibrosis and diabetes and whether these relationships vary by age or disease group.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, adolescents (N=128; M=14.7 yrs) diagnosed with cystic fibrosis or diabetes completed measures of spiritual coping and attributional style. Adolescents and their caregivers reported on adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems.

Results

Overall, positive spiritual coping was associated with fewer internalizing and externalizing problems. Negative spiritual coping was related to more externalizing problems, and for adolescents with cystic fibrosis only, also internalizing problems. Optimistic attributions mediated the effects of positive spiritual coping among adolescents with diabetes. The results did not vary by age.

Conclusions

An optimistic attribution style may help explain the effects of positive, but not negative, spiritual coping on adjustment of youth with diabetes. Youth with progressive, life-threatening illnesses, such as cystic fibrosis, may be more vulnerable to the harmful effects of negative spiritual coping. Future research should examine if addressing spiritual concerns and promoting optimistic attributions improves adolescents’ emotional and behavioral functioning.

Keywords: chronic illness, spiritual coping, attribution style, adolescents, adjustment

Introduction

“Is my illness a punishment from God?” “God, can you help me endure this pain?” Although not always addressed in clinical practice, spiritual issues like these rise to the forefront for pediatric patients who grapple with the meaning and purpose of their illness. Spiritual issues become especially salient when these children enter adolescence due to normative developments in abstract thinking [1] and faith-based reasoning [2]. Spiritual beliefs, both positive and negative, serve as coping resources when others are not as available or effective [3]. Indeed, the use of positive and negative spiritual coping (also called religious coping) has been demonstrated among youth with various chronic conditions [4,5]. Positive spiritual coping reflects the use of faith for comfort during difficult times, while negative spiritual coping reflects struggle, doubt, or abandonment by a God-figure [3].

Spiritual coping is an important predictor of mental health among pediatric patients, who generally experience more internalizing and externalizing problems than healthy youth [6]. Positive spiritual coping has been linked with lower emotional distress in youth with asthma or cystic fibrosis [7] and fewer post-traumatic stress symptoms among youth with diabetes, cancer, or epilepsy [8]. Negative spiritual coping has been associated with more internalizing problems and worse quality of life among pediatric asthma patients, even after accounting for secular coping and other covariates [9]. Spiritual coping was also more strongly linked to emotional well-being in adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease compared to healthy peers [10]. Since all these studies examined internalizing problems, it is unclear whether spiritual coping also predicts externalizing problems in pediatric populations. Only one study addressed this question and found no relationship, but the measure of spiritual coping in this study was limited [8].

The mechanisms through which spiritual coping may affect adjustment in pediatric populations have not been studied. We propose that cognitive attributional style, or how people appraise life events [11], may partly explain the relationship. Attributions can be made along multiple dimensions, such as stability, locus of control, and globality. Typically, these dimensions cluster into an overall pattern of more optimistic vs. pessimistic attributions, with optimistic attributions characterized by stable, internal, and global appraisals of positive events (“I succeeded because I tried hard”) and unstable, external, and specific appraisals of negative events (“I failed because the situation was difficult”). Pediatric patients who endorse pessimistic attributions are more likely to develop internalizing and externalizing problems [12–14] than those who utilize optimistic attributional styles. Previous literature has established the role of spiritual beliefs in the reappraisal of negative events [15], but whether these beliefs impact an individual’s attributional style and related adjustment has not been directly studied. For instance, positive or negative spiritual coping may promote more optimistic or pessimistic attributions, respectively, of difficult events, which in turn affect adjustment. Identifying attributional style as a mediator may provide a cognitive framework for pediatric psychologists and other health-care professionals to address spiritual distress.

Furthermore, little is known about possible age or disease differences. The relationships between spiritual coping, attributions, and adjustment may be stronger, for instance, among older, cognitively more developed adolescents, and among youth with more severe diseases that activate spiritual concerns about life after death. Identifying age or disease differences may lead to specialized care for specific pediatric populations.

Thus, the present study evaluates whether attributional style mediates the relationship between spiritual coping and adjustment of adolescents with chronic illness, and whether these relationships vary by age or disease. We hypothesize that positive spiritual coping will predict fewer internalizing and externalizing problems, while negative spiritual coping will predict more adjustment problems, and that these effects will be mediated by more optimistic or pessimistic attributions, respectively. We also expect that these effects will be stronger among older adolescents and youth with cystic fibrosis.

Method

Participants

Participants included 128 adolescents diagnosed with type 1 diabetes (n=82) or cystic fibrosis (n=46) and their caregivers. Adolescents (M=14.7 years, SD=1.8) included 53% males and 84% Caucasians, 12% African Americans, and 4% other ethnicities. A summary of demographic information is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Means, Standard Deviations, and Percentages

| Variable | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Female (%) | 59 | 46.90 |

| Minority (%) | 21 | 16.40 |

| M | SD | |

|

| ||

| Age | 14.71 | 1.78 |

| Family Incomea | 7.72 | 2.91 |

| Years since Diagnosis | 8.54 | 4.67 |

| Physician Rating of Severity | −0.00 | 1.00 |

| Positive Spiritual Coping | 2.06 | 0.74 |

| Negative Spiritual Coping | 0.49 | 0.50 |

| Optimistic Attributional Style | 6.00 | 3.22 |

| Hyperactivity (P) | 13.03 | 3.54 |

| Hyperactivity (A) | −0.00 | 0.66 |

| Aggression (P) | 14.45 | 3.54 |

| Conduct Problems (P) | 18.61 | 3.93 |

| Depression (P) | 19.18 | 4.52 |

| Depression (A) | −0.01 | 0.57 |

| Anxiety (P) | 20.06 | 4.53 |

| Anxiety (A) | −0.02 | 0.60 |

family income was rated on an 11-point scale from 1 ($10,000 or less annually) to 11 (greater than $100,000 annually)

P: Parent report of adolescent behavior on BASC

A: Adolescent self-report of behavior on BASC, converted to z-scores

Procedure

University Institutional Review Board approval was obtained. Study procedures have been previously described [16] and are summarized here. Adolescents were recruited during outpatient medical visits at a children’s hospital in the southeast U.S. during years 2008–2009. Inclusion criteria included fluency in English and no known diagnosis of a Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Mental Retardation, or Psychosis. Eligible adolescents ages 12–18 and one caregiver were recruited to participate (75% participation rate). After providing written informed consent and assent, participants completed questionnaires during their visit or mailed them in after completion at home. Written and verbal instructions were provided during recruitment. Each adolescent/caregiver dyad was compensated for their time.

Measures

Demographics

Caregivers reported the child’s ethnicity, gender, and age. Ethnicity was recoded into two categories, Caucasian and racial/ethnic minority. Caregivers also reported on the family’s annual income, as well as on key disease-related variables, including years since diagnosis. Physicians rated adolescents’ disease severity using a single-item developed for this study, ranging from 1 (very mild) to 4 (very severe). Scores were converted to z-scores within each disease group to form the scale.

Spiritual coping

Adolescents completed the Brief RCOPE, a self-report measure of positive and negative religious/spiritual coping strategies that has been validated in both pediatric and adult samples [3,4]. The 14 items (7 positive and 7 negative) are rated on a 4-point scale (“not at all” [0] to “a great deal” [3]) and averaged (α=.90 and .73). Positive spiritual coping includes seeking spiritual support or collaboration from God, as well as benevolent religious reappraisals (e.g., spiritual strengthening). Negative spiritual coping includes spiritual discontentment, negative reappraisals of God’s powers, or demonic reappraisals. Higher scores indicate higher levels of positive and negative spiritual coping, respectively.

Adolescent adjustment

Caregivers and adolescents completed the Behavioral Assessment System for Children-Second Edition (BASC-2) [17]. The BASC-2 includes 150–176 statements rated on a 4-point scale (“never” to “always”) or rated true/false. Four clinical scales were used to measure externalizing problems: caregiver-reported conduct problems (14-items; α=.87), aggression (10-items; α=.82), and hyperactivity (8-items; α=.80); and adolescent self-reported hyperactivity (7-items; α=.78). The self-report BASC-2 does not include aggression and conduct problems subscales. Internalizing problems were assessed with caregiver-reported depression and anxiety scales (13- and 11 items; α=.84 and .77), and adolescent self-reported depression and anxiety scales (12- and 13 items; α=.84 and .85). Raw scores were used rather than T-scores due to their greater variability, particularly at low levels of psychopathology [18]. This allowed us to exclude somaticizing items from the Anxiety scales to prevent confounding by adolescents’ medical problems, as recommended in the literature [19]. On the caregiver form, all items were rated on the 4-point scale and summed. On the adolescent form, some items were rated on the 4-point scale, but others were dichotomous (true/false). Thus, all items were converted into z-scores and averaged to form the scales. Higher scores indicate more adjustment problems.

Attributional style

Adolescents’ attributional style was assessed with the Children’s Attributional Styles Questionnaire Revised (CASQ-R) [20]. The CASQ-R contains 24-hypothetical situations (“A team that you are on loses a game”) about which adolescents make ratings of stability, locus of control, and globality. Positive and negative attributional style scale scores were computed, and a composite was derived as positive minus negative. Higher scores on the composite indicate more optimistic attributions. Internal consistencies of the positive and negative subscales were consistent with previous research on this measure [20] (α=.51 and .55). Despite its low reliability, the scale has good predictive validity for internalizing problems in pediatric populations [13,20].

Statistical Analyses

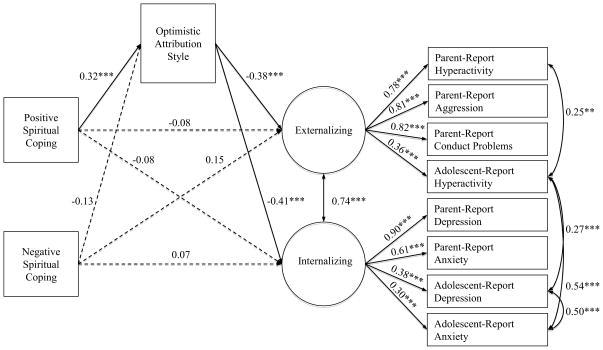

The data were examined for outliers and assumptions of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Descriptive analyses identified 6 outliers on the outcome variables, which were truncated to scores corresponding to 3.5 standard deviations above or below the mean. No significant violations of normality or other assumptions were detected, and scatterplots confirmed linear relationships among continuous variables. Bivariate relationships among variables were examined with Pearson’s correlations and t tests. The effects of positive and negative spiritual coping on mental health and the mediating role of attributions were analyzed with SEM in Mplus version 5.2 [21]. Internalizing and externalizing problems were modeled as latent factors based on the BASC-2 scales reported by caregiver/adolescent dyads (see Figure 1). All paths were adjusted for demographic variables that were related to predictor or outcome variables (see Figure 1). Based on modification indices, theoretically meaningful covariances between specific pairs of adjustment variables were added to improve model fit (e.g., between adolescent- and caregiver-reported hyperactivity; see Figure 1) [22,23]. An acceptable model fit is indicated by a comparative fit index (CFI) over .90, Tucker Lewis index (TLI) over .80, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) of .08 or less [24]. Some authors also recommend that the ratio of χ2 to degrees of freedom be less than 2–3 [22,23]. The first model tested the direct links between positive and negative spiritual coping and internalizing and externalizing models. The second model added attributions as a partial mediator of these effects.

Figure 1.

Final mediation model of the indirect relationships between adolescent spiritual coping and psychological adjustment. All paths were adjusted for adolescent age, gender, ethnicity, annual family income, time since diagnosis, and physician rating of severity.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Multigroup modeling was utilized to examine age differences between younger (12–14 years; n=60) and older (15–18 years; n=68) adolescents and disease differences between cystic fibrosis (n=46) and diabetes (n=82) in the SEM models. Consistent with established guidelines [25], the structural part of the model (i.e., “causal” paths) was tested for equivalence, whereas the measurement part of the model (i.e., loadings on latent factors of internalizing and externalizing problems) was held constant across groups in all models. The χ2 difference tests compared the unconstrained model, where structural paths were allowed to vary across the two age- or disease-groups, respectively, with the constrained model, where the structural paths were fixed to be equal for the two groups. Significant differences would indicate age or disease differences and were followed by similar testing of differences in specific paths of the model.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

The means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables are presented in Table 1. Correlations among continuous variables are presented in Table 2. Notably, positive spiritual coping was associated with more optimistic attributional style (p<.001) and fewer caregiver-reported conduct problems (p<.05). Negative spiritual coping was related to higher levels of caregiver-reported conduct problems (p<.05) and self-reported internalizing problems (p<.001). Optimistic attributional style was related to fewer adjustment problems per both reporters (p<.05).

Table 2.

Correlations of Demographic, Predictor, and Outcome Variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 2 | Family Incomea | 0.01 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Years Since Diagnosis | 0.25** | −0.30** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 4 | Physician Rating of Severityb | 0.00 | −0.25** | 0.17 | 1 | ||||||||||

| 5 | Positive Spiritual Coping | −0.16 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.11 | 1 | |||||||||

| 6 | Negative Spiritual Coping | 0.14 | −0.07 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.14 | 1 | ||||||||

| 7 | Optimistic Attributional Style | −0.10 | 0.11 | −0.11 | −0.10 | 0.32** | −0.09 | 1 | |||||||

| 8 | Hyperactivity (P) | −0.02 | −0.01 | 0.11 | 0.01 | −0.14 | 0.08 | −0.35** | 1 | ||||||

| 9 | Hyperactivity (A) | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.06 | −0.02 | −0.11 | 0.10 | −0.22* | 0.41** | 1 | |||||

| 10 | Aggression (P) | 0.08 | −0.05 | 0.07 | 0.00 | −0.17 | 0.08 | −0.31** | 0.63** | 0.27** | 1 | ||||

| 11 | Conduct Problems (P) | 0.18* | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.20* | 0.23* | −0.39** | 0.68** | 0.30** | 0.65** | 1 | |||

| 12 | Depression (P) | 0.10 | −0.07 | 0.12 | 0.10 | −0.15 | 0.03 | −0.36** | 0.45** | 0.24** | 0.60** | 0.54** | 1 | ||

| 13 | Depression (A) | 0.20* | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.15 | 0.37** | −0.44** | 0.33** | 0.39** | 0.26** | 0.43** | 0.32** | 1 | |

| 14 | Anxiety (P) | 0.20* | 0.05 | 0.19* | 0.01 | −0.15 | 0.02 | −0.27** | 0.21* | 0.16 | 0.36** | 0.26** | 0.57** | 0.11 | 1 |

| 15 | Anxiety (A) | 0.20* | 0.07 | 0.11 | −0.03 | −0.15 | 0.30** | −0.25** | 0.12 | 0.54** | 0.11 | 0.24** | 0.25** | 0.55** | 0.23* |

p < .05,

p < .01 or lower

family income was rated on an 11-point scale from 1 ($10,000 or less annually) to 11 (greater than $100,000 annually)

physicians report of disease severity from 1 (very mild) to 4 (very severe), standardized within disease group

P: parent report of adolescent behavior on BASC; A: adolescent self-report of behavior on BASC

Table 3 presents t tests among dichotomous variables. Adolescents reported higher levels of positive than negative spiritual coping (M=2.06 vs. .49, p<.001). The disease groups only differed on time since diagnosis, which was longer for adolescents with cystic fibrosis (M=12.30 vs. 6.43 years, p<.001). Because age was dichotomized for the multigroup models, we compared younger (12–14 years) and older (15–18 years) youth on other variables. Older adolescents reported more anxiety (M=.11 vs. −.16, p<.01) and depression (M=.09 vs. −.12, p<.05) than younger adolescents. In contrast to a nonsignificant correlation between age (as a continuous variable) and negative spiritual coping, when examined as a group, older youth expressed higher levels of negative spiritual coping than younger youth (M=.59 vs. .39, p<.05).

Table 3.

Summary of Mean Differences between Dichotomous Variables

| Diabetes vs. Cystic Fibrosis | Younger vs. Older | Caucasian vs. Minority | Male vs. Female | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Incomea | 7.98 vs. 7.26 | 7.63 vs. 7.79 | 8.13 vs. 5.62** | 7.81 vs. 7.62 |

| Years since Diagnosis | 6.43 vs. 12.30** | 7.80 vs. 9.19 | 8.47 vs. 8.88 | 7.93 vs. 9.23 |

| Physician Rating of Severityb | −0.00 vs. 0.00 | 0.01 vs. −0.01 | −0.14 vs. 0.73** | −0.12 vs. 0.14 |

| Positive Spiritual Coping | 2.05 vs. 2.08 | 2.12 vs. 2.01 | 2.02 vs. 2.23 | 1.97 vs. 2.16 |

| Negative Spiritual Coping | 0.51 vs. 0.46 | 0.39 vs. 0.59* | 0.43 vs. 0.83** | 0.52 vs. 0.46 |

| Optimistic Attributional Style | 6.16 vs. 5.71 | 6.24 vs. 5.79 | 6.03 vs. 5.86 | 5.81 vs. 6.22 |

| Hyperactivity (P) | 12.64 vs. 13.70 | 13.25 vs. 12.83 | 13.12 vs. 12.57 | 13.63 vs. 12.34* |

| Hyperactivity (A) | −0.04 vs. 0.05 | −0.05 vs. 0.03 | 0.01 vs. −0.07 | 0.06 vs. −0.07 |

| Agression (P) | 14.70 vs. 14.01 | 14.25 vs. 14.62 | 14.54 vs. 14.00 | 14.85 vs. 13.99 |

| Conduct Problems (P) | 18.62 vs. 18.61 | 17.94 vs. 19.20 | 18.59 vs. 18.73 | 18.76 vs. 18.44 |

| Depression (P) | 19.05 vs. 19.41 | 18.81 vs. 19.49 | 19.11 vs. 19.52 | 18.18 vs. 20.32** |

| Depression (A) | −0.02 vs. −0.00 | −0.12 vs. 0.09* | −0.04 vs. 0.14 | 0.01 vs. −0.03 |

| Anxiety (P) | 19.89 vs. 20.38 | 19.31 vs. 20.72 | 20.14 vs. 19.69 | 19.24 vs. 21.02* |

| Anxiety (A) | −0.02 vs. −0.02 | −0.17 vs. 0.10* | −0.05 vs. 0.12 | −0.10 vs. 0.08 |

p < .05,

p < .01 or lower

family income was rated on an 11-point scale from 1 ($10,000 or less annually) to 11 (greater than $100,000 annually)

physicians report of disease severity from 1 (very mild) to 4 (very severe), standardized within disease group

P: parent report of adolescent behavior on BASC

A: adolescent self-report of behavior on BASC, converted to z-scores

Main Analyses

The SEM model predicting externalizing and internalizing problems from positive and negative spiritual coping had acceptable fit [22–24] to the data [χ2(63)=104.41, p<.001; CFI=.91; TLI=.87; RMSEA=.07]. Positive and negative spiritual coping were unrelated (β=.14, p=.11). Positive spiritual coping was associated with fewer externalizing and internalizing problems (β= −.21 and −.19, p<.05). Negative spiritual coping was related to more externalizing problems (β=.20, p<.05) but not internalizing problems (β=.10, p=.33). The mediation model (see Figure 1) had an acceptable fit [22–24] to the data [χ2(69)=120.16, p<.001; CFI=.90; TLI=.84; RMSEA=.08], and with attributions in the model, spiritual coping no longer directly predicted adjustment. Negative spiritual coping was unrelated to attributional style, and thus attributions did not mediate the effects of negative spiritual coping on adjustment. Positive spiritual coping was related to more optimistic attributions, which in turn predicted fewer externalizing and internalizing problems (indirect effects of positive spiritual coping to externalizing and internalizing via attributions: β= −.12 and −.13, p<.01).

The multigroup analyses indicated the presence of disease group differences in both the direct effects and mediational models [Δχ2(21)=34.84 and Δχ2(31)=47.03, both p<.05]. Follow-up tests indicated that the link between negative spiritual coping and internalizing problems varied by disease [Δχ2(1)=9.85, p<.01]. In both models, negative spiritual coping was associated with internalizing problems among adolescents with cystic fibrosis, but not among those with diabetes (mediation model: β=.49, p<.01 vs. β =−.07, p=.44). Positive spiritual coping was related to more optimistic attributions among adolescents with diabetes, but not among those with cystic fibrosis (mediation model: β=.47, p<.001 β=.08,vs. p=.57). Thus, optimistic attributional style mediated the effects of positive spiritual coping on externalizing and internalizing problems only among adolescents with diabetes [Δχ2(1)=4.64, p<.05]. The multigroup analyses revealed no age differences [direct effects model: Δχ2(18)=26.30; mediation model: Δχ2(25)=35.54, both p>.05].

Discussion

Adolescents with chronic illness often struggle with spiritual issues, but our understanding of the role of spiritual coping in their mental health is limited. This study examined the direct effects of positive and negative spiritual coping on adolescents’ adjustment, the role of attributions as a mediator of these effects, and age and disease differences in these relationships. Consistent with previous research [7–10], the results provide support for the importance of spiritual coping in both internalizing and externalizing problems of pediatric patients. Overall, positive spiritual coping was associated with fewer internalizing and externalizing problems and negative spiritual coping was related to more externalizing problems. Disease differences in the effects of spiritual coping and attributions emerged. Negative spiritual coping played a role in internalizing problems only for adolescents with cystic fibrosis, whereas attributions were related to positive spiritual coping only in those with diabetes. Thus, more optimistic attributions partly mediated the relationship between positive spiritual beliefs and fewer adjustment difficulties only among adolescents with diabetes. No age differences in the relationships emerged in this sample of 12–18 year olds.

Spiritual Coping, Adjustment, and Attributions

Our finding that positive spiritual coping predicts fewer internalizing problems is consistent with previous research [7,10], but this is the first study to also show a link to fewer externalizing problems. It is possible that positive spiritual coping strategies are used to buffer not only feelings of anxiety and depression, but also behavior problems that might arise from the illness experience. The overall results indicated that externalizing problems were also predicted by higher levels of negative spiritual coping. It is possible that negative spiritual coping may contribute to behavior problems by increasing adolescents’ perceptions that difficult situations are not within their control [26]. Contrary to previous research [9], negative spiritual coping was unrelated to more internalizing problems overall. The relationship did emerge, however, among adolescents with cystic fibrosis, suggesting that it may be specific to youth with more severe conditions. Future research should explore these hypotheses using longitudinal and qualitative designs, as well as larger samples from multiple disease groups.

Among adolescents with diabetes, optimistic attributional style explained the relationships between positive spiritual coping and adjustment, suggesting that positive spiritual beliefs may promote more external, unstable, and specific attributions for negative events that may in turn buffer feelings of helplessness or distress [11]. Youth with diabetes are frequently exposed to negative disease-related events that are difficult to control. For instance, they may fail to maintain glucose control simply because of fluctuating hormones [27]. By using positive spiritual coping strategies (e.g., trusting God to use the situation to strengthen them), they may reappraise the poor glucose reading as an unstable event that they are not personally responsible for but from which they can learn [27]. Hence, using positive spiritual coping may reduce their distress and acting-out by promoting optimistic attributions towards negative disease-related events [28]. These speculations need to be tested in future research.

Interestingly, negative spiritual coping was unrelated to attributional style, suggesting that other factors may explain the relationship to behavior problems. One possible mediator is diminished religious social support [29]. Qualitative data indicate the importance of support from religious communities for pediatric populations [5]. Future research should explore whether pediatric patients who engage in negative spiritual coping withdraw from their religious community, thereby deepening feelings of isolation and leading to more behavior difficulties. Other possible mediators, such as meaning of life concerns, health behaviors, or stress should be examined as well [29].

Age and Disease Differences

Consistent with prior research [5,15], both younger and older adolescents reported higher levels of positive than negative spiritual coping. However, older adolescents reported more negative spiritual coping compared to younger adolescents, perhaps a reflection of more developed cognitive skills and ability to grasp long-term consequences of their illness [30]. Nonetheless, spiritual coping played an equally important role in the adjustment of younger and older youth, underscoring the need to address these concerns in clinical care across adolescence.

The disease groups did not differ in their use of spiritual coping or adjustment problems. However, negative spiritual coping was related to more internalizing problems only among adolescents with cystic fibrosis, suggesting that these youth may be more vulnerable to its harmful effects. Their vulnerability may stem from the progressive, life-threatening nature of cystic fibrosis compared to diabetes, and may be exacerbated by isolation due to frequent hospitalizations and separation from other patients with cystic fibrosis because of the risk of cross-infection [31]. By contrast, optimistic attributional style mediated the effects of positive spiritual coping on adjustment only among adolescents with diabetes, suggesting that other explanatory mechanisms may be present for youth with cystic fibrosis (e.g., low perceived social support). Future research exploring age or disease differences will benefit from obtaining larger sample sizes and considering alternative mediators, such as social support, religious involvement, or religious health practices (e.g., no drinking) [29].

Clinical Implications

These findings on the importance of spiritual coping in adjustment highlight the need for clinicians to assess spiritual coping when they suspect adjustment difficulties, and to consider spiritual issues as an important part of the adolescent’s psychosocial functioning. Helping adolescents address negative spiritual coping and explore positive spiritual coping, while also developing more optimistic general attributions, may translate into better psychosocial adjustment. The spiritual needs of these adolescents may be best addressed by a multidisciplinary approach involving chaplains. Other health professionals can screen for negative spiritual coping, particularly if the patient is exhibiting adjustment difficulties, using validated measures as part of psychosocial assessments [3,32] and refer for counseling if significant spiritual distress is identified.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions

This study extended existing literature by linking spiritual coping with both internalizing and externalizing problems, testing general attributions as a mediator of these relationships, and examining age and disease differences. Methodological strengths include the latent variable modeling of multi-informant measures. However, the interpretations are limited by the study’s cross-sectional design, which does not allow inferences about the directionality of the relationships studied. For instance, it is possible that optimistic attributions promote positive spiritual coping, or that both positive spiritual coping and optimistic attributions are indicators of a higher-order latent trait construct of “positivity.” Future research should examine these alternatives. Inferences are also limited by the unknown psychometric properties of the disease severity measure developed for this study and low reliability of the attribution measure, which has emerged across studies [20,33]. Also, the limited variability of the negative spiritual coping scale, perhaps stemming from individuals’ reluctance to report these strategies [15], likely constrained the magnitude of its correlations with other variables. The small sample size may also limit interpretations, despite sufficient power (>.90) to detect acceptably fitting models with the present sample size [34]. Also, the acceptable (versus good) fit of our models may be a result of the small sample size, high complexity of the models, and inclusion of data from multiple informants.

The results may not generalize to other geographic locations with patterns of religious affiliations distinct from the present, predominantly Christian southeastern U.S. [35]. The results may also not generalize to families with characteristics similar to those who declined to participate; unfortunately, information on these families was not collected to determine whether systematic bias was present. Future research should clarify the causal relationships between spiritual coping, attributions, and mental health using larger samples, longitudinal designs, more reliable, validated measures, and by replicating the results in other pediatric populations.

In conclusion, this study provides novel and clinically relevant findings about the role of spiritual coping in adjustment of adolescents with chronic illness. The results suggest that positive spiritual coping is partly related to better adjustment indirectly through optimistic attributions. Negative spiritual coping is related to more behavior problems, and also to more internalizing problems among adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Future research should examine whether these findings extend to youth with other progressive diseases. The effects of negative spiritual coping were not explained by an attributional style, suggesting the need to explore alternative mediators. Spiritual coping, as well as attributions, should be assessed among pediatric patients exhibiting emotional or behavioral problems and may be improved through cognitive interventions and pastoral care. Improving spiritual and secular coping may enhance psychosocial adjustment, and should be explored through intervention and longitudinal research designs.

Implications and Contribution.

Spiritual coping is an important predictor of mental health in youth with chronic health conditions. It may affect mental health partly by facilitating more positive interpretations of life events. Clinicians should assess for spiritual distress, particularly among youth with psychosocial adjustment difficulties or more severe conditions.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported in part by grants from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and from the Sigma Xi Grants-in-Aid of Research program to the third author and grant K01DA024700 from the National Institutes of Health to the second author.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Piaget J. Part I: Cognitive development in children: Piaget development and learning. J Res Sci Teach. 1964;2(3):176–186. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fowler JW. Stages of Faith : The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning. San Francisco, CA: Harper & Row; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J Sci Study Relig. 1998;37(4):710–724. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cotton S, Grossoehme D, Rosenthal SL, et al. Religious/spiritual coping in adolescents with sickle cell disease: A pilot study. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(5):313–318. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31819e40e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pendleton SM, Cavalli KS, Pargament KI, Nasr SZ. Religious/spiritual coping in childhood cystic fibrosis: a qualitative study. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):E8. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinquart M, Shen Y. Behavior problems in children and adolescents with chronic physical illness: a meta-analysis. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(9):1003–1016. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsr042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shelton S, Linfield K, Carter B, Morton R. Spirituality and coping with chronic life-threatening pediatric illness: Cystic fibrosis and severe asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:520. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zehnder D, Prchal A, Vollrath M, Landolt MA. Prospective study of the effectiveness of coping in pediatric patients. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2006;36(3):351–368. doi: 10.1007/s10578-005-0007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benore ER, Pargament KI, Pendleton S. An initial examination of religious coping in children with asthma. Int J Psychol Relig. 2008;18(4):267–290. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotton S, Kudel I, Roberts YH, et al. Spiritual well-being and mental health outcomes in adolescents with or without inflammatory bowel disease. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44(5):485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peterson C, Semmel A, von Baeyer C, Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Seligman ME. The attributional style questionnaire. Cognit Ther Res. 1982;6(3):287–299. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frank NC, Blount RL, Brown RT. Attributions, coping, and adjustment in children with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 1997;22(4):563–576. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoenherr SJ, Brown RT, Baldwin K, Kaslow NJ. Attributional styles and psychopathology in pediatric chronic-illness groups. J Clin Child Psychol. 1992;21(4):380–387. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maurice-Stam H, Oort FJ, Last BF, Brons PP, Caron HN, Grootenhuis MA. School-aged children after the end of successful treatment of non-central nervous system cancer: Longitudinal assessment of health-related quality of life, anxiety and coping. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2009;18(4):401–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2008.01041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pargament KI, Hahn J. God and the just world: Causal and coping attributions to god in health situations. J Sci Study Relig. 1986;25(2):193–207. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guion K, Mrug S. The role of parental and adolescent attributions in adjustment of adolescent with chronic illness. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012;20:20. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9288-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds C, Kamphaus R. Behavior Assessment System for Children Second Edition: Manual. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heflinger CA, Simpkins CG, Combs-Orme T. Using the CBCL to determine the clinical status of children in state custody. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2000;22(1):55–73. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cruz I, Marciel K, Quittner A, Schechter M. Anxiety and depression in cystic fibrosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;30(5):569–578. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1238915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson M, Kaslow NJ, Weiss B, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Children’s attributional style questionnaire revised: Psychometric examination. Psychol Assessment. 1998;10(2):166–170. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mplus Version 5.2 [computer program] Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 3. New York: The Guilford Press; 2011. p. 189. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ullman JB. Structural equation modeling. In: Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS, editors. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. pp. 653–771. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacKinnon D. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson NS, Garber J, Hilsman R. Cognitions and stress - direct and moderating effects on depressive versus externalizing symptoms during the junior-high-school transition. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104(3):453–463. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McLaughlin E, Lefaivre MJ, Cummings E. Experimentally-induced learned helplessness in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2010;35(4):405–414. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conley CS, Haines BA, Hilt LM, Metalsky GI. The children’s attributional style interview: Developmental tests of cognitive diathesis-stress theories of depression. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2001;29(5):445–463. doi: 10.1023/a:1010451604161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park CL. Religiousness/spirituality and health: A meaning systems perspective. J Behav Med. 2007;30(4):319–328. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cotton S, McGrady ME, Rosenthal SL. Measurement of religiosity/spirituality in adolescent health outcomes research: Trends and recommendations. J Relig Health. 2010;49(4):414–444. doi: 10.1007/s10943-010-9324-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tuchman LK, Schwartz LA, Sawicki GS, Britto MT. Cystic fibrosis and transition to adult medical care. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):566–573. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fitchett G, Risk JL. Screening for spiritual struggle. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2009;63(1–2):4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis SP, Waschbusch DA. Alternative approaches for conceptualizing children’s attributional styles and their associations with depressive symptoms. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25(9):E37–46. doi: 10.1002/da.20322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacCallum RC, Browne MW, Sugawara HM. Power analysis and determination of sample size for covariance structure modeling. Psychol Methods. 1996;1(2):130–149. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kosmin BA, Mayer E, Keysar A. American religious identification survey 2001. New York, NY: Graduate Center of the City University of New York; 2001. [Google Scholar]