Abstract

The bifunctional enzyme UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase/ManNAc kinase (GNE) catalyzes the first two committed steps in sialic acid synthesis. Non-allosteric GNE gene mutations cause the muscular disorder GNE myopathy (also known as hereditary inclusion body myopathy), whose exact pathology remains unknown. Increased knowledge of GNE regulation, including isoform regulation, may help elucidate the pathology of GNE myopathy. While eight mRNA transcripts encoding human GNE isoforms are described, we only identified two mouse Gne mRNA transcripts, encoding mGne1 and mGne2, homologous to human hGNE1 and hGNE2. Orthologs of the other human isoforms were not identified in mice. mGne1 appeared as the ubiquitously expressed, major mouse isoform. The mGne2 encoding transcript is differentially expressed and may act as a tissue-specific regulator of sialylation. mGne2 expression appeared significantly increased the first two days of life, possibly reflecting the high sialic acid demand during this period. Tissues of the knock-in Gne p.M712T mouse model had similar mGne transcript expression levels among genotypes, indicating no effect of the mutation on mRNA expression. However, upon treatment of these mice with N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc, a Gne substrate, sialic acid precursor, and proposed therapy for GNE myopathy), Gne transcript expression, in particular mGne2, increased significantly, likely resulting in increased Gne enzymatic activities. This dual effect of ManNAc supplementation (increased flux through the sialic acid pathway and increased Gne activity) needs to be considered when treating GNE myopathy patients with ManNAc. In addition, the existence and expression of GNE isoforms needs consideration when designing other therapeutic strategies for GNE myopathy.

Keywords: GNE myopathy, isoforms, mouse, UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase/ManNAc kinase

Introduction

Uridine diphosphate (UDP)-N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc) kinase (GNE), is the bifunctional key enzyme of sialic acid biosynthesis, and is encoded by the GNE gene [1,2]. The GNE enzyme consists of 722 amino acids, encoding two enzymatic domains. The N-terminal domain (amino acid 1-378) carries out UDP-GlcNAc epimerase function, whereas the C-terminal domain (amino acids 410-722) is responsible for ManNAc kinase activity. In mammals, the end product of sialic acid synthesis, cytidine monophosphate-N-acetylneuraminic acid (CMP-Neu5Ac), feedback-inhibits GNE-epimerase activity by binding to its allosteric site (amino acids 263-266) [3,4]. Neu5Ac is the most abundant mammalian sialic acid and the precursor of most naturally existing sialic acids [5]. Sialic acids are negatively charged, terminal residues on glycoconjugates, and assist in many cellular recognition, interaction and proliferation events, both in healthy and malignant cells [5,6].

We recently demonstrated that apart from the reported 3 human GNE isoforms (GNE1-3) [7,8], five additional novel human isoforms (GNE4-8) exist and display a tissue-specific expression and different structural features with respect to catalytic activity, ligand binding and allosteric regulation [9]. However, it remains unknown which role these isoforms play in GNE regulation, or GNE-related disease pathology.

The human disorder GNE myopathy or Hereditary Inclusion Body Myopathy (HIBM; OMIM#600737), and its allelic Japanese disorder, Distal Myopathy with Rimmed Vacuoles (DMRV; OMIM#605820), are associated with predominantly missense mutations in GNE. GNE myopathy is autosomal recessive inherited and characterized by adult onset, slowly progressive muscle weakness and atrophy. More than 1000 GNE myopathy patients are estimated to exist worldwide, harboring over 80 GNE mutations. These mutations lead to decreased (but not absent) GNE enzymatic activities and, presumably, decreased sialic acid production [2,10,11].

To further study the pathology of GNE myopathy and to test possible treatment methods, mouse models of the disease were created. A complete Gne knockout was embryonic lethal [12]. A transgenic mouse that expressed the human GNE cDNA with the p.D176V mutation, common among Japanese patients, was created on a mouse background with a disrupted mouse Gne gene. This transgenic Gne p.D176V mouse model (Gne(-/-)hGNED176V-Tg) recapitulated the adult onset features of human GNE myopathy. Biochemically, the mouse presented with hyposialylation in serum and different organs [13]. A second GNE myopathy knock-in mouse model was created by homologous recombination through introducing the p.M712T mutation, common among Persian-Jews, into the endogenous mouse Gne gene. Surprisingly, these knock-in Gne p.M712T mouse mutants died within 72 hours of birth from severe glomerular disease. Biochemical analysis of mutant mouse kidneys revealed decreased Gne expression and activity as well as deficient sialylation of the major podocyte sialoproteins, podocalyxin and nephrin, suggesting that decreased production of sialic acid may be responsible for early lethality in these mice [14,15]. The mutant mice did not live long enough to study possible adult onset muscle pathology. Oral administration of the sialic acid precursor, N-acetyl-mannosamine (ManNAc), rescued the muscle phenotype in the transgenic Gne p.D176V mouse [16] and partially rescued the glomerular disease and early lethality in the knock-in Gne p.M712T mouse model [14]. The fact that human GNE myopathy patients have no indications of renal abnormalities, and display only a muscle phenotype, led us to further explore whether tissue- and species-specific expression of GNE isoforms could help explain these findings. In addition, we utilized the knock-in Gne p.M712T mouse model to explore effects of ManNAc supplementation on Gne isoform expression, which may aid in development of human clinical treatment protocols.

In mice, two different mouse Gne mRNA splice variants were previously described, Gne1 and Gne2 [17]. Here we explore the existence of other mouse Gne transcripts encoding additional isoforms, demonstrate differential Gne transcript expression in a variety of mouse tissues, including in wild type, knock-in Gne p.M712T, and ManNAc supplemented mice, and perform molecular modeling studies, in an attempt to explain the differences between human and mouse GNE myopathy phenotypes, as well as to predict the effects of proposed GNE myopathy therapies on isoform expression.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics

For sequence homology searches, the Protein Data Bank (pdb; http://www.pdb.org/pdb/home/home.do), the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) BLAST searches (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), as well as the Blat searches provided by the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) genome browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgBlat) were employed.

Modeling of mGne and hGNE isoforms

Secondary structure predictions for the 31-residue N-terminal extension of the mGne2 and hGNE2 isoforms were performed by four methods: GOR V (Garnier-Osguthorpe-Robson) [18,19], FDM (Fragment Database Mining) [20], CDM (Consensus Data Mining) [21], and PSIPRED (Protein Structure Initiative Prediction) [22]. The mGne2 N-terminal extension was aligned with similar fragments of other proteins for analysis of the presence of important catalytic residues (Table 1).

Table 1.

Amino acid similarities between the N-terminal 31 amino acid extension of mGne2 and other homologous proteins

| Protein/source/pdb code/ | aa #a | Sequence alignmentb |

|---|---|---|

| mGne2 extension | 1-31 | METHAHLHREQSYAGPHELYFKKLSSKKKQV |

| hGNE2 extension | 1-31 | METYGYLQRESCFQGPHELYFKNLSKRNKQI |

| SGK1/H. sapiens /2r5t/ | 183-202 | ELFYHLQRERCFLEPRARFY |

| His kinase/ A. avenae/ | 198-213 | FLQRERCFAGDASHEL |

| His kinase/ P. carotovorum/ | 194-219 | DELERFLQRERCFVSDASHELRTPLA |

| His kinase/ H. arsenicoxydans/ | 193-216 | AELQQFLARERFFTGDVSHELRTP |

| Ser/Thr protein kinase/H. sapiens /2vx3/ | 104-131 | HHHHHSSGVDLGTENLYFQSMSSHKKE |

| DYRK2/H. sapiens /3k2l/ | 107-122 | EIYFLGLNAKKRQG |

| PRPP amidotransferase/B. subtilis/1ao0/ | 18-48 | YGLHSLQHRGQEGAGIVATDGEKLTAHKGQG |

| PRPP amidotransferase /E. coli/1ecb/ | 18-48 | DALTVLQHRGQDAAGIITIDANDCFRLRKAN |

| VAV1/H. sapiens/ 3bji | 465-495 | KWSHMFLLIEDQGAQGYELFFKTRELKKKWM |

| Carbonic anhydrase IV/H. sapiens /1znc/ | 217-247 | QLHREQILAFSQKLYYDK |

| GCNA/S. gordonii /2epl/ | 51-81 | SYKQPHQLY |

| Oxidoreductase/E. coli/1tlt/ | 149-165 | HRSNS-VGPHDLYFTLL |

| Deoxyribonuclease/T. maritima /1j6o/ | 1-11 | VDTHAHLHFHQ |

aa #: amino acid number

Shaded: identical amino acids; double underlined: α-helices; underlined: ß-sheets. No secondary structure data are known about protein fragments lacking underlining

Mouse studies

Knock-in Gne p.M712T mice were generated as previously described [14]. All mice were maintained in the C57BL/6J background. Animals were housed in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International-accredited specific pathogen-free facility in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH publication no. 85-23). All mouse procedures were performed in accordance with protocol G04-3 approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Human Genome Research Institute. ManNAc was acquired from New Zealand Pharmaceuticals. ManNAc treatment was performed by retro-orbital injection [23] of ManNAc embedded in liposomes (ManNAc-Lipoplex) to whole litters at postnatal day 1 (P1) [24]. Untreated mice were euthanized at P1, P2, or P5. All ManNAc treated mice were euthanized at P5. All euthanasia was performed by CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation. For the treatment experiments we studied heterozygous (rather than wild type) tissues after ManNAc treatment, since heterozygous female mice were mated with mutant male mice, to yield a high percentage (50%) of mutants per experiment, but these did not yield any wild type pups. Heterozygous mice show no phenotype and no difference in mGne mRNA expression compared to wild type mice [14]. For embryonic tissue collection, pregnant mice at embryonic day 17 (E17) were euthanized, embryos were retrieved by cesarean section and euthanized by decapitation.

RNA and cDNA

RNA was extracted from mouse tissues using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Tissue-specific RNA was purchased from Clontech (mouse Total RNA Master Panels). cDNA was created from all RNA using a High Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Mouse multiple tissue cDNA panel I was purchased from Clontech (Clontech Laboratories).

Transcript-Specific PCR

Primers were designed for transcript-specific PCR amplification of predicted mouse Gne splice variants (Table S1). All PCR reactions were performed with HotStarTaq polymerase, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). PCR products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis and selected bands were excised (QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit, Qiagen) and directly sequenced using BigDye Terminator v3.1 chemistry and an ABI 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

Quantitative real-time PCR

TaqMan primers and probes were custom designed for splice variant specific sequences using the ABI Assay-by-Design service (Table S2) (Applied Biosystems). The housekeeping gene B2M (β2 microglobulin; Mm00437762) was used as internal control gene. All quantitative real-time PCR reactions and subsequent analyses were performed on an ABI PRISM 7900 HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems). The pre-run thermal cycling conditions were 10 min at 95°C to activate the Taq DNA-polymerase, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C annealing/extension for 1 min. Each experiment was performed in triplicate. Within each experiment, reactions were run in triplicate. Relative gene expression levels were determined by the comparative threshold cycle method (ddCt) [25]. For statistical analysis of the expression data, the independent samples t-test was employed (Tables S3a and S3b).

Results

Identification of mouse Gne isoform transcripts

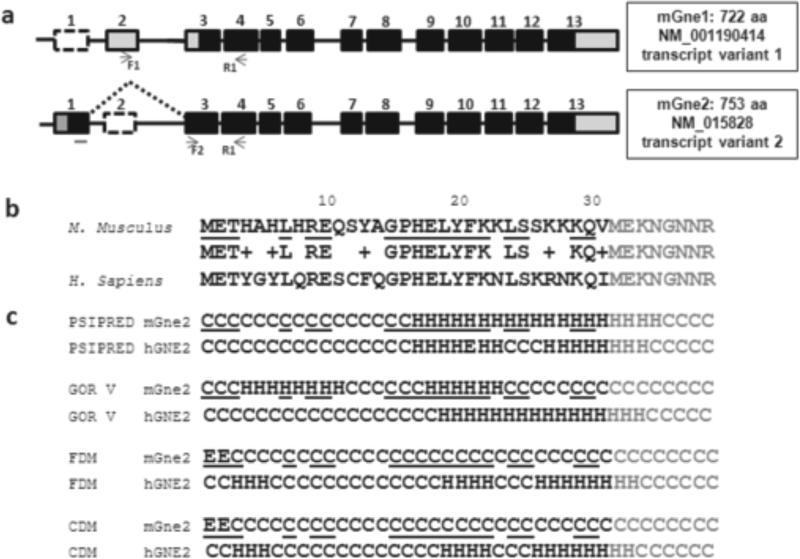

The mouse Gne gene consists of 13 exons, similar to the human gene. Two mRNA transcripts exist, resulting from alternative splicing of 5’ exons 1, 2 and 3, encoding 2 protein open reading frames, i.e., mGne1 (NM_001190414) and mGne2 (NM_015828) (Fig. 1a), as previously described [26]. Our bioinformatic database searches and PCR amplification results did not identify orthologs of the other six human isoforms (hGNE3-hGNE8) in mouse tissues.

Fig. 1. Mouse Gne transcripts, sequence alignment and secondary structure prediction of N-terminal extension of mGne2.

a. Exon (boxes)-intron (lines) structures of mouse Gne transcripts mGne1 and mGne2. GenBank Accession numbers and predicted numbers of translated amino acids (aa) are indicated. Black boxes illustrate the open reading frame, gray boxes the untranslated mRNA regions, and dashed boxes the skipped exons of each transcript. Primer locations for transcript-specific PCR amplifications (Fig. 2) are indicated below each isoform. Note that the forward primer F2 is localized across exon1-exon3 boundaries.

b. Amino acid sequence alignment of the 31 residue N-terminal extensions of mouse mGne2 and human hGNE2, show only 58% identity and 74% homology. Black, 31 amino acid N-terminal extensions; Gray: overlap with mGne1 and hGNE1 amino acids; Underlined: identical amino acids in mGne2 compared to hGNE2; +: homologous amino acids.

c. Secondary structure predictions with 4 prediction methods (PSIPRED, GOR V, FDM, and CDM) of the N-terminal 31-residue extension mGne2 show significant differences between mGne2 and hGNE2. Black, 31 amino acid N-terminal extensions; Gray: overlap with mGne1 and hGNE1 amino acids; Underlined: identical amino acids in mGne2 compared to hGNE2; C, coil; H, α-helices; E, β-strands.

The mGne1 protein is homologous to hGNE1 (encoded by human transcript variant 2, GenBank NM_005476), the human isoform described in all previous biochemical and mutation analysis studies [1,2,27]; both mGne1 and hGNE1 consist of 722 amino acids with their translation start codons in exon 3, considered nucleotide 1 in this study and all previous GNE (mutation) reports. The mGne2 protein is homologous to human hGNE2 (encoded by human transcript variant 1, NM_001128227), both have their translation start codons in exon 1 at nucleotide -93, yielding a 753 amino acids protein with a 31-amino acid extension at the N-terminus compared to mGne1/hGNE1 (Fig. 1).

Modeling of mouse Gne isoforms

mGne1 and hGNE1 are 98.75% identical (713/722 amino acids) and 99.45% homologous (718/722 amino acids). Three of the four amino acids in mGne1 that are non-homologous to hGNE1 (E37A, S211C, and L534Q) are located in coil regions and one non-homologous amino acid, A636V, is located in an α-helix. The four homologous amino acid changes between mGne1 and hGNE1 are all located in the ManNAc kinase activity encoding domain of Gne; N447S and L523M in an α-helix domain, and R481Q and I484V in a coil domain. Our modeling analysis showed that these changes in mGne1 are not affecting secondary structure compared to hGNE1 (Fig. S1). The only amino acid change that may affect kinase enzymatic function and/or folding between hGNE and mGne is L523M. Even though the Methionine in mGne preserves the hydrophobic character of the Leucine amino acid in hGNE, it introduces a larger side chain that may contribute to specificity of helix-helix interface interactions and may influence substrate binding and phosphorylation. The amino acid L523 in hGNE is located in the α4-helix [amino acids 516-528] of Domain I (N-lobe) of the kinase domain and is predicted to be completely immersed into the protein interior (only 5% of its area is exposed to solvent) and interacts with the α10-helix [amino acids 703-717] of the Domain II (C-lobe) of the kinase domain, which includes amino acid M712. This site is important for orientation of the two kinase subdomains (lobes) and affects GlcNAc, Mg2+, and ATP binding [28,29].

mGne2 and hGNE2 are 97.08% identical (731/753 amino acids) and 98.41% homologous (741/753 amino acids). These changes include the same 8 changes mentioned above for mGne1 versus hGNE1, which are not affecting secondary structure predictions. However, the mouse mGne2 N-terminal extension of 31 amino acids is only 58.1% identical (18/31 amino acids) and 74% homologous (23/31) to that of human GNE2 (Fig. 1b). Secondary structure predictions for this extension differ significantly between mGne2 and hGNE2, in all four prediction programs (Fig. 1c). Note that secondary structure predictions of the mGne2 or hGNE2 extensions compared to themselves is very similar between prediction programs (Fig. 1c). The mGne2 N-terminal extension has similarity to some protein fragments that were also homologous to the hGNE2 extension [9], in particular with the human serum and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1 (SGK1) and histidine (His) kinases of different organisms (Table 1). SGK1 contains an intermolecular disulfide bond [30] in the region homologous to the mGne2 and hGNE2 N-terminal extensions. In SGK1, this region is predicted to come in close contact with an activation loop of the neighboring subunit and with its phosphorylation site [30]. Interestingly, a cysteine residue is present in the N-terminal extension of hGNE2 (at residue 12), as well as in the homologous SGK1 sequence and in several homologous His kinases (Table 1). In addition, SGK1 (residues 175-240) harbors another 25% homologous region to Gne (residues 370-471 of mGne1/hGNE1). This region is located between the epimerase and kinase enzymatic domains and contains a cysteine at residue 388. The cysteine residues C12 and C388 were predicted candidates for disulfide bonds, whether intermolecular (as in SGK1) or intramolecular (possibly between GNE regions) [9]. However, mGne2 lacks this cysteine residue, and may therefore harbor different enzymatic properties, binding sites or secondary structure in its N-terminal region than hGNE2. Moreover, mGne2 has homologies to other protein fragments, which have lower homology to the hGNE2 extension, including other kinases (a Ser/Thr protein kinase and dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation regulated kinase 2 (DYRP2)) (Table 1), whether these homologies predict similarities in structural or binding properties is a subject of future studies.

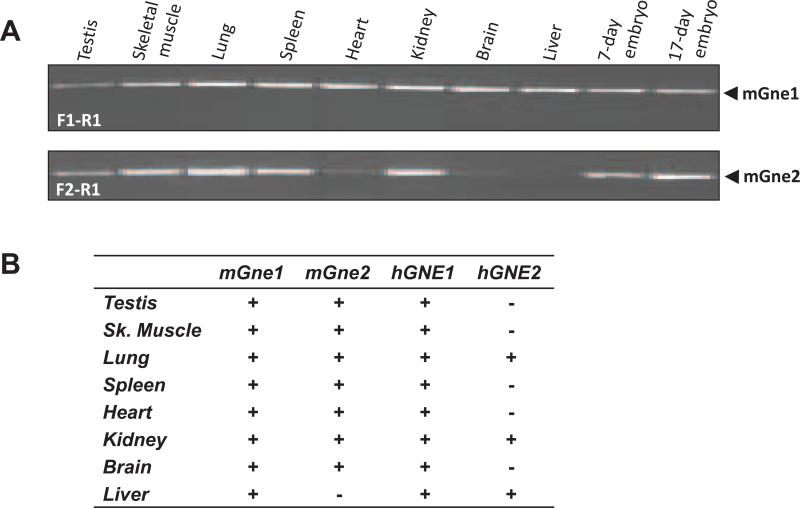

Tissue-specific expression of mGne1 and mGne2 encoding transcripts

Tissue-specific PCR amplification of mouse cDNA tissue panels revealed that both mouse mGne encoding transcripts were expressed in all tissues tested, except for liver which lacked mGne2 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Tissue-specific expression of mGne isoform transcripts.

a. PCR amplification of tissue-specific cDNA from selected mouse tissues. Primers and amplified transcripts are indicated.

b. Summary of mGne1 and mGne2 compared with hGNE1 and hGNE2 tissue-specific transcript expression.

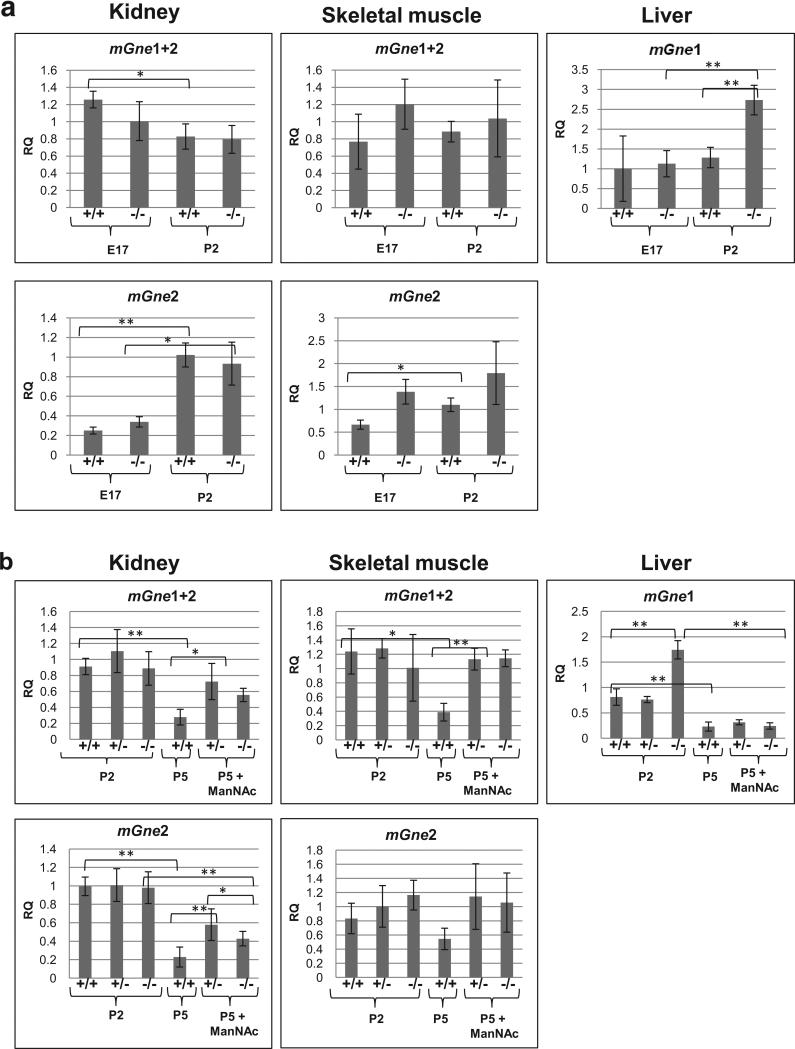

Expression of mGne isoforms in knock-in Gne p.M712T mice

For mGne transcript expression in the knock-in p.M712T mouse model, we analyzed kidney and skeletal muscle expression, because they display a GNE myopathy phenotype. And, additionally, liver was included because this is the only mouse tissue without mGne2 transcript expression. In kidney and skeletal muscle, there was no significant difference in mGne1 or mGne2 transcript expression between wild type (+/+) and mutant (-/-) tissues at the same age (P2 or embryonic day 17 (E17), Fig. 3a). mGne2 transcript levels were increased dramatically (significant in most cases) at P2 compared to E17 in both genotypes (Fig. 3a). Livers expressed more (significant in mutant tissues) mGne1 transcript at P2 compared to E17, similar to the mGne2 transcript increase at P2 in kidney and skeletal muscle.

Fig. 3. Gne expression in tissues of the ‘M712T knock-in’ mouse model.

qPCR results of isoform-specific mGne expression in kidney, skeletal muscle and liver tissues of the knock-in Gne p.M712T mouse model: +/+, wild type; +/-, heterozygous; -/-, mutant. Transcript-specific Taqman primer-probe assays were used (see Table S2), as indicated above each panel. Displayed values represent the relative quantification (RQ) normalized to B2M with expression in wild type (+/+) at P2 set to 1 for each Taqman probe. P -values 0.01-0.05 (*), <0.01(**) (Statistical data are displayed in Tables S3a and S3b).

a. mGne tissue-specific transcript expression at embryonic day 17 (E17) and postnatal day 2 (P2).

b. mGne tissue-specific transcript expression in untreated tissues at P2 (all genotypes) and P5 (wild type only), and in tissues after ManNAc treatment at P5 (heterozygous and mutant).

Fig. 3b compares mGne transcript expression in tissues from mice that did not receive ManNAc (wild type only at P5, since untreated mutant mice die before P3 of severe glomerulopathy [14]) to those that received ManNAc (mutant and heterozygous). Heterozygous mice have no phenotype [14] and showed similar mGne transcript expression levels compared with wild type mice (Fig. 3b, tissues at P2). All untreated wild type tissues showed significantly decreased mGne transcript levels (both mGne1 and mGne2) at P5 compared to P2. After ManNAc treatment, mGne transcript levels appeared to be significantly increased in kidney and skeletal muscle, compared to untreated tissues at P5. Liver did not show this response to ManNAc treatment. There was no apparent difference in mGne transcript expression between genotypes after ManNAc treatment, with the exception of mGne2 transcript expression in kidney, which appeared to be slightly upregulated in mutant tissue.

Discussion

GNE (isoform) expression and localization are important modulators of sialylation [9,31-33], and may play an important role in the pathology of GNE myopathy. Humans have eight GNE isoforms (hGNE1-hGNE8) [9], and mice only have two isoforms, mGne1 and mGne2 [8], with high homologies of 99.5% and 98.4% to hGNE1 and hGNE2, respectively. The GNE gene may be subject to evolutionary mechanisms by which the number of cellular functions can be increased, without increasing the number of genes [9,34].

mGne1, like hGNE1, is ubiquitously expressed (Fig. 2) [9] and differs from hGNE1 in only 8 amino acids, located in structurally non-important regions. Both have a similar predicted secondary structure (displayed in [9] and [29], Fig. S1). Recombinantly expressed mGne1 and hGNE1 were previously shown to both occur in the tetrameric (full enzyme activity) and dimeric (kinase activity only) states, with comparable epimerase and kinase activities [17]. These studies suggest that mGne1 and hGNE1 likely have similar biochemical functions.

mGne2 is identical to mGne1, with the exception of a novel 31-amino acids N-terminal extension (similar to hGNE2). Even though the N-terminal extensions of mGne2 and hGNE2 are encoded by homologous exons in the Gne/GNE genes, the amino acids of both fragments varied dramatically in composition (only 58.1% identity, Fig. 1b), secondary structure predictions (Fig. 1c), and homologies to fragments of other proteins (Table 1). mGne2 is expressed in all murine tissues tested, with the exception of liver; a pattern that is significantly different from hGNE2 expression (Fig. 2b). Recombinantly expressed mGne2 predominantly exists in the tetrameric state with full epimerase and kinase enzymatic activities, while hGNE2 predominantly exist in the dimeric state with a lack of epimerase activity [17]. The reduced homology of the mGne2 and hGNE2 N-termini apparently influences oligomer formation and the difference in epimerase activities. These results implicate that mGne2 and hGNE2 have different biochemical properties, likely due to independent evolutionary pathways.

We used our knock-in Gne p.M712T mouse model to further study the response of mGne isoform expression to age, sialylation status and sialylation increasing therapy. First, we demonstrated that the M712T mutation does not directly affect Gne mRNA expression levels. Second, we showed that mGne expression is highly responsive to age. In kidney and skeletal muscle (the two affected tissues in Gne p.M712T mice), mGne2 expression increased dramatically at P2 compared to E17 in all genotypes (Fig. 3a). This effect is likely a response to the increased sialic acid demand in the first few days of life [35]. A similar increase was seen for mGne1 encoding transcripts in liver (the major organ of sialic acid synthesis, which lacks mGne2 expression), especially in mutant liver. Contrarily, at P5, mGne expression in kidney and skeletal muscle were significantly decreased compared to expression at P2 (Fig. 3b). These results agree with the decrease in sialic acid demand after the first two days of life [35]. Third, after ManNAc treatment, mGne2 transcript expression in kidney and skeletal muscle at P5 was considerably increased compared to untreated tissues at P5. Note that liver mGne1 transcripts did not show this response to ManNAc treatment. These mouse studies suggest that mGne2 transcripts are more sensitive to ManNAc treatment and sialic acid demands than mGne1 transcripts. This may be attributed to particular sensitivity of an element of the mGne2 transcript promotor to sialic acid (or ManNAc) concentration, which could be explored in future studies.

It remains greatly unknown whether monosaccharides (such as ManNAc) can directly influence gene transcription, and if so, whether they act through binding to promotor regions or whether they act as second messenger [12,31,36]. It is also intriguing to investigate CMP-sialic acid-regulated gene expression since this is produced in the nucleus [37].

Future studies may also reveal whether hGNE transcript expression in human GNE myopathy tissues have age-specific and treatment-specific responses similar to GNE myopathy mouse tissues. Tissue-specific hGNE/mGne isoform expression differences between human and mice may explain why the knock-in Gne p.M712T mouse develops severe glomerular disease and GNE myopathy patients have no indications of renal abnormalities. However, other factors may play a role as well, since humans and mice may differ in the relative importance of sialic acid to the kidney, and their protein glycosylation patterns also vary [38,39], Of interest is that the transgenic Gne p.D176V mouse model, which is constructed such that it only expresses mGne1 transcripts [13], does not develop a severe kidney phenotype. This may indicate that mGne2 is not required for viability, but that mGne2 expression may ‘fine-tune’ or regulate (tissue-specific) sialylation.

Increased knowledge of GNE (isoform) regulation may help elucidate the pathology of GNE myopathy, as well as of other disorders of hyposialylation. Isoform expression needs to be considered when designing and evaluating treatment strategies, such the therapies currently under development for GNE myopathy patients, including ManNAc (www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT01634750) or sialic acid (Neu5Ac) (www.clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01517880) supplementation, or GNE gene therapy [40,41]. Although no direct comparison between mouse (2 predicted mGne isoforms) and human GNE-isoform (8 predicted hGNE isoforms) related pathology could be made, we demonstrated that mouse Gne transcript expression, in particular mGne2, increased significant upon ManNAc treatment. This possibly dual effect of ManNAc supplementation (increased flux through sialic acid pathway and increased GNE activity) needs to be considered when treating GNE myopathy patients with ManNAc. A similar effect may occur upon sialic acid treatment. In addition, the existence and regulation of GNE isoforms needs to be considered when designing GNE myopathy gene therapy strategies [40,41].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the expert laboratory work of Dr. Shelley Hoogstraten-Miller, Katherine Berger, Katherine Patzel, and Adrian Astiz-Martinez. The authors thank Theresa Calhoun for her skilled assistance with mouse maintenance. We thank the HIBM Research group (Encino, CA) for providing the knock-in Gne p.M712T mouse model. This work was performed in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a PhD degree of T.Y., Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Israel. This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, United States (T.Y., K.J., T.K.N., C.C., W.A.G., and M.H.) and Research Funds of The School of Theoretical Modeling, Chevy Chase, Maryland, United States (N.K.).

Abbreviations

- A. avenae

Acidovorax avenae

- B2M

β2 microglobulin

- BLAST

Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

- B. subtilis

Bacillus subtilis

- CDM

Consensus Data Mining

- CMP

Cytidine monophosphate

- DMRV

Distal Myopathy with Rimmed Vacuoles

- DYRK2

Dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation regulated kinase 2

- E

Embryonic day

- E. coli

Escherichia coli

- FDM

Fragment Database Mining

- GCNA

N-acetyl-B-D-glucosaminidase

- GlcNAc

N-acetylglucosamine

- GNE

UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase/ManNAc kinase

- GOR

Garnier-Osguthorpe-Robson

- H. arsenicoxydans

Herminiimonas arsenicoxydans

- HIBM

Hereditary Inclusion Body Myopathy

- His

Histidine

- H. sapiens

Homo sapiens

- Min

Minutes

- ManNAc

N-acetylmannosamine

- NCBI

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- Neu5Ac

N-acetylneuraminic acid

- OMIM

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man

- P

Postnatal day

- P. carotovorum

Pectobacterium carotovorum

- PCR

- Pdb

Protein databank

- PRPP

Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate

- PSIPRED

Protein Structure Initiative Prediction

- qPCR

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- SGK1

Serum and glucocorticoid-induced kinase 1

- S. gordonii

Streptococcus gordonii;

- T. maritime

Thermotoga maritima

- UDP

Uridine diphosphate

- VAV1

Vav-family member of guanine nucleotide exchange factors

References

- 1.Hinderlich S, Stasche R, Zeitler R, Reutter W. A bifunctional enzyme catalyzes the first two steps in N-acetylneuraminic acid biosynthesis of rat liver. Purification and characterization of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:24313–24318. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg I, Avidan N, Potikha T, Hochner H, Chen M, Olender T, Barash M, Shemesh M, Sadeh M, Grabov-Nardini G, Shmilevich I, Friedmann A, Karpati G, Bradley WG, Baumbach L, Lancet D, Asher EB, Beckmann JS, Argov Z, Mitrani-Rosenbaum S. The UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase gene is mutated in recessive hereditary inclusion body myopathy. Nat. Genet. 2001;29:83–87. doi: 10.1038/ng718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kornfeld S, Kornfeld R, Neufeld EF, O'Brien PJ. The Feedback Control of Sugar Nucleotide Biosynthesis in Liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1964;52:371–379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.52.2.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seppala R, Lehto VP, Gahl WA. Mutations in the human UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase gene define the disease sialuria and the allosteric site of the enzyme. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1999;64:1563–1569. doi: 10.1086/302411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X, Varki A. Advances in the biology and chemistry of sialic acids. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010;5:163–176. doi: 10.1021/cb900266r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varki NM, Varki A. Diversity in cell surface sialic acid presentations: implications for biology and disease. Lab. Invest. 2007;87:851–857. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watts GD, Thorne M, Kovach MJ, Pestronk A, Kimonis VE. Clinical and genetic heterogeneity in chromosome 9p associated hereditary inclusion body myopathy: exclusion of GNE and three other candidate genes. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2003;13:559–567. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(03)00070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reinke SO, Hinderlich S. Prediction of three different isoforms of the human UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3327–3331. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yardeni T, Choekyi T, Jacobs K, Ciccone C, Patzel K, Anikster Y, Gahl WA, Kurochkina N, Huizing M. Identification, Tissue Distribution, and Molecular Modeling of Novel Human Isoforms of the Key Enzyme in Sialic Acid Synthesis, UDP-GlcNAc 2-Epimerase/ManNAc Kinase. Biochemistry. 2011;50:8914–8925. doi: 10.1021/bi201050u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huizing M, Krasnewich DM. Hereditary inclusion body myopathy: a decade of progress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1792:881–887. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noguchi S, Keira Y, Murayama K, Ogawa M, Fujita M, Kawahara G, Oya Y, Imazawa M, Goto Y, Hayashi YK, Nonaka I, Nishino I. Reduction of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase activity and sialylation in distal myopathy with rimmed vacuoles. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:11402–11407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313171200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarzkopf M, Knobeloch KP, Rohde E, Hinderlich S, Wiechens N, Lucka L, Horak I, Reutter W, Horstkorte R. Sialylation is essential for early development in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2002;99:5267–5270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072066199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malicdan MC, Noguchi S, Nonaka I, Hayashi YK, Nishino I. A Gne knockout mouse expressing human GNE D176V mutation develops features similar to distal myopathy with rimmed vacuoles or hereditary inclusion body myopathy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:2669–2682. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galeano B, Klootwijk R, Manoli I, Sun M, Ciccone C, Darvish D, Starost MF, Zerfas PM, Hoffmann VJ, Hoogstraten-Miller S, Krasnewich DM, Gahl WA, Huizing M. Mutation in the key enzyme of sialic acid biosynthesis causes severe glomerular proteinuria and is rescued by N-acetylmannosamine. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:1585–1594. doi: 10.1172/JCI30954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kakani S, Yardeni T, Poling J, Ciccone C, Niethamer T, Klootwijk ED, Manoli I, Darvish D, Hoogstraten-Miller S, Zerfas P, Tian E, Ten Hagen KG, Kopp JB, Gahl WA, Huizing M. The Gne M712T mouse as a model for human glomerulopathy. Am. J. Pathol. 2012;180:1431–1440. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malicdan MC, Noguchi S, Hayashi YK, Nonaka I, Nishino I. Prophylactic treatment with sialic acid metabolites precludes the development of the myopathic phenotype in the DMRV-hIBM mouse model. Nat. Med. 2009;15:690–695. doi: 10.1038/nm.1956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reinke SO, Lehmer G, Hinderlich S, Reutter W. Regulation and pathophysiological implications of UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase/ManNAc kinase (GNE) as the key enzyme of sialic acid biosynthesis. Biol. Chem. 2009;390:591–599. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garnier J, Osguthorpe DJ, Robson B. Analysis of the accuracy and implications of simple methods for predicting the secondary structure of globular proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 1978;120:97–120. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90297-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kloczkowski A, Ting KL, Jernigan RL, Garnier J. Combining the GOR V algorithm with evolutionary information for protein secondary structure prediction from amino acid sequence. Proteins. 2002;49:154–166. doi: 10.1002/prot.10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng H, Sen TZ, Kloczkowski A, Margaritis D, Jernigan RL. Prediction of protein secondary structure by mining structural fragment database. Polymer. (Guildf) 2005;46:4314–4321. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2005.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sen TZ, Cheng H, Kloczkowski A, Jernigan RL. A Consensus Data Mining secondary structure prediction by combining GOR V and Fragment Database Mining. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2499–2506. doi: 10.1110/ps.062125306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bryson K, McGuffin LJ, Marsden RL, Ward JJ, Sodhi JS, Jones DT. Protein structure prediction servers at University College London. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W36–38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yardeni T, Eckhaus M, Morris HD, Huizing M, Hoogstraten-Miller S. Retro-orbital injections in mice. Lab. Anim. (NY) 2011;40:155–160. doi: 10.1038/laban0511-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yardeni T, Ciccone C, Hoogstraten-Miller S, Darvish D, Anikster Y, Maples PB, Jay CM, Gahl WA, Nemunaitis J, Huizing M. A Non-Viral, GNE-Lipoplex Treatment to Correct Sialylation Defects in Gne-Mutant (M712T) Mice.. Proceedings of the American Society for Gene & Cell Therapy, Annual Meeting; Washington, DC. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reinke SO, Eidenschink C, Jay CM, Hinderlich S. Biochemical characterization of human and murine isoforms of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase (GNE). Glycoconj. J. 2009;26:415–422. doi: 10.1007/s10719-008-9189-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eisenberg I, Grabov-Nardini G, Hochner H, Korner M, Sadeh M, Bertorini T, Bushby K, Castellan C, Felice K, Mendell J, Merlini L, Shilling C, Wirguin I, Argov Z, Mitrani-Rosenbaum S. Mutations spectrum of GNE in hereditary inclusion body myopathy sparing the quadriceps. Hum. Mutat. 2003;21:99. doi: 10.1002/humu.9100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tong Y, Tempel W, Nedyalkova L, Mackenzie F, Park HW. Crystal structure of the N-acetylmannosamine kinase domain of GNE. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7165. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurochkina N, Yardeni T, Huizing M. Molecular modeling of the bifunctional enzyme UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase/ManNAc kinase and predictions of structural effects of mutations associated with HIBM and sialuria. Glycobiology. 2010;20:322–337. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao B, Lehr R, Smallwood AM, Ho TF, Maley K, Randall T, Head MS, Koretke KK, Schnackenberg CG. Crystal structure of the kinase domain of serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 in complex with AMP PNP. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2761–2769. doi: 10.1110/ps.073161707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keppler OT, Hinderlich S, Langner J, Schwartz-Albiez R, Reutter W, Pawlita M. UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase: a regulator of cell surface sialylation. Science. 1999;284:1372–1376. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krause S, Hinderlich S, Amsili S, Horstkorte R, Wiendl H, Argov Z, Mitrani-Rosenbaum S, Lochmuller H. Localization of UDP-GlcNAc 2-epimerase/ManAc kinase (GNE) in the Golgi complex and the nucleus of mammalian cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2005;304:365–379. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghaderi D, Strauss HM, Reinke S, Cirak S, Reutter W, Lucka L, Hinderlich S. Evidence for dynamic interplay of different oligomeric states of UDP-N-acetylglucosamine 2-epimerase/N-acetylmannosamine kinase by biophysical methods. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;369:746–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yogev O, Pines O. Dual targeting of mitochondrial proteins: mechanism, regulation and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1808:1012–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Duncan PI, Raymond F, Fuerholz A, Sprenger N. Sialic acid utilisation and synthesis in the neonatal rat revisited. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kontou M, Weidemann W, Bork K, Horstkorte R. Beyond glycosylation: sialic acid precursors act as signaling molecules and are involved in cellular control of differentiation of PC12 cells. Biol. Chem. 2009;390:575–579. doi: 10.1515/BC.2009.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kean EL, Munster-Kuhnel AK, Gerardy-Schahn R. CMP-sialic acid synthetase of the nucleus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1673:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kershaw DB, Beck SG, Wharram BL, Wiggins JE, Goyal M, Thomas PE, Wiggins RC. Molecular cloning and characterization of human podocalyxin-like protein. Orthologous relationship to rabbit PCLP1 and rat podocalyxin. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:15708–15714. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chou HH, Takematsu H, Diaz S, Iber J, Nickerson E, Wright KL, Muchmore EA, Nelson DL, Warren ST, Varki A. A mutation in human CMP-sialic acid hydroxylase occurred after the Homo-Pan divergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1998;95:11751–11756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nemunaitis G, Maples PB, Jay C, Gahl WA, Huizing M, Poling J, Tong AW, Phadke AP, Pappen BO, Bedell C, Templeton NS, Kuhn J, Senzer N, Nemunaitis J. Hereditary inclusion body myopathy: single patient response to GNE gene Lipoplex therapy. J. Gene Med. 2010;12:403–412. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nemunaitis G, Jay CM, Maples PB, Gahl WA, Huizing M, Yardeni T, Tong AW, Phadke AP, Pappen BO, Bedell C, Allen H, Hernandez C, Templeton NS, Kuhn J, Senzer N, Nemunaitis J. Hereditary Inclusion Body Myopathy: Single Patient Response to Intravenous Dosing of GNE Gene Lipoplex. Hum. Gene Ther. 2011;22:1331–1341. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.