Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a positive sense, single-stranded RNA virus in the Flaviviridae family. It causes acute hepatitis with a high propensity for chronic infection. Chronic HCV infection can progress to severe liver disease including cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. In the last decade, our basic understanding of HCV virology and life cycle has advanced greatly with the development of HCV cell culture and replication systems. Our ability to treat HCV infection has also been improved with the combined use of interferon, ribavirin and small molecule inhibitors of the virally encoded NS3/4A protease, although better therapeutic options are needed with greater antiviral efficacy and less toxicity. In this article, we review various aspects of HCV life cycle including viral attachment, entry, fusion, viral RNA translation, posttranslational processing, HCV replication, viral assembly and release. Each of these steps provides potential targets for novel antiviral therapeutics to cure HCV infection and prevent the adverse consequences of progressive liver disease.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, Virology, Life cycle

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a hepatotropic RNA virus of the genus Hepacivirus in the Flaviviridae family, originally cloned in 1989 as the causative agent of non-A, non-B hepatitis.1,2 It causes acute and chronic hepatitis in humans and chimpanzees with a high propensity for chronicity. If untreated, chronic hepatitis C can progress to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in a subset of patients.3 Until recently, the standard of care for patients with chronic hepatitis C involved dual therapy with pegylated interferon (IFN) alpha and ribavirin (PEG IFN/riba) in most countries. Dual PEG IFN/riba therapy achieved sustained virological response (SVR) in only 50% of patients infected with the more common HCV genotype (genotype 1) compared to 80% SVR rate in patients infected with HCV genotype 2 or 3.4 Moreover, combined PEG IFN/riba therapy is costly and prolonged (e.g. 24-48 weeks) with numerous adverse effects that are difficult to tolerate. In 2011, two inhibitors of the virally encoded NS3/4A protease became available as a part of standard therapy in some countries, especially against HCV genotype 1. Triple therapy combining one of these first-generation protease inhibitors with PEG IFN/riba therapy has improved SVR rate from around 50% to 70% in some clinical trial cohorts,5-8 However, this new regimen has limited efficacy in certain special populations (e.g. cirrhotic patients, transplant recipients, primary non-responders and hemodialysis patients) due to underlying IFN resistance, emergence of protease inhibitor resistance mutations and/or increased drug toxicity. Thus, there are ongoing efforts towards better therapeutic options with shorter treatment duration with less toxicity and drug resistance-preferably as IFN-free, all oral combination regimens.

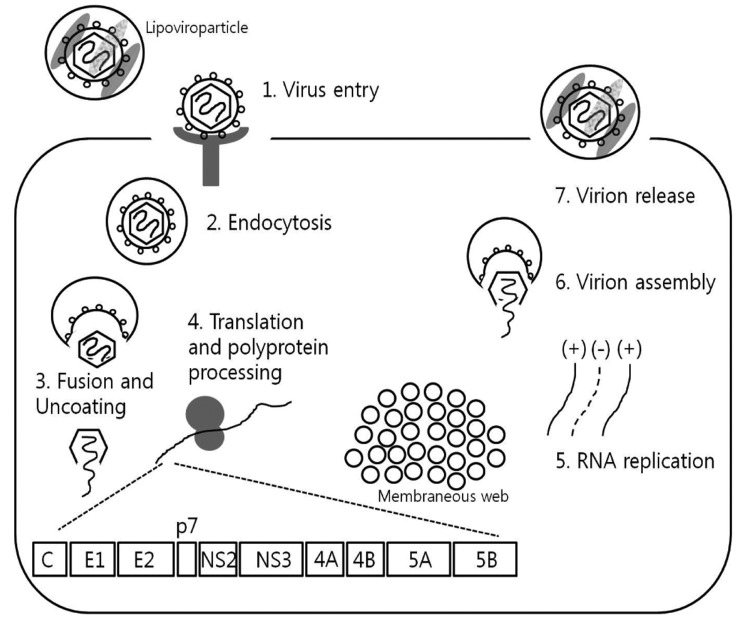

The recent HCV therapeutic development has been greatly enhanced by basic understanding of HCV virology and life cycle, through studies using HCV cell culture systems and replication assays. In this article, we review various steps in HCV life cycle that also serve as relevant targets for potential novel therapeutics, including viral attachment, entry, fusion, viral RNA translation, posttranslational processing, HCV replication, viral assembly and release (Fig. 1).9

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the HCV life cycle. Every step of the life cycle offers a variety of potential targets for novel therapeutics (Adapted from Ploss A, et al. Gut 2012;61(Suppl 1):i25-i35).9

HCV genome and its products

HCV is a positive-sense, single-stranded enveloped RNA virus approximately 9600 nucleotides in length. Approximately 1012 viral particles are generated daily in chronically HCV-infected patient.10 Due to the highly error prone RNA polymerase, HCV also displays remarkable genetic diversity and propensity for selection of immune evasion or drug resistance mutations.11 There are 6 major HCV genotypes (numbered 1-6) that vary by over 30% in nucleotide sequence from one another.12 The HCV genome has one continuous open reading frame flanked by nontranslated regions (NTRs) at 5' and 3' ends. The HCV 5'NTR contains 341 nucleotides located upstream of the coding region and is composed of 4 domains (numbered I to IV) with highly structured RNA elements including numerous stem loops and a pseudoknot.13,14 The 5' NTR also contains the internal ribosome entry site (IRES), that initiates the cap-independent translation of HCV genome into a single polyprotein15 by recruiting both viral proteins and cellular proteins such as eukaryotic initiation factors (eIF) 2 and 3.16-18

The HCV open reading frame contains 9024 to 9111 nucleotides depending on the genotype. It encodes a single polyprotein that is cleaved by host and viral proteases into 10 individual viral proteins with various characteristics.19

Structural proteins

HCV core is the viral nucleocapsid protein with numerous functionalities involving RNA binding, immune modulation, cell signaling, oncogenic potential and autophagy. HCV core protein also associates with the lipid droplets where HCV assembly also takes place. HCV E1/E2 are glycosylated envelope glycoproteins that surround the viral particles. HCV envelope is targeted by virus neutralizing antibody selection pressure with high degree of sequence variation that may render antibody responses ineffective and contributes to HCV persistence.20-22 The small ion channel protein p7 is downstream of the envelope region and is required for viral assembly and release.

Nonstructural proteins

NS2 is the viral autoprotease that plays a key role in viral assembly, mediating the cleavage between NS2 and NS3. NS3 encodes the N-terminal HCV serine protease and C-terminal RNA helicase-NTPase. NS3 protease play a critical role in HCV processing by cleaving downstream of NS3 at 4 sites (between NS3/4A, NS4A/4B, NS4B/NS5A, NS5A/NS5B). It also cleaves the TLR3 adaptor protein TRIF and mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein MAVS, thereby blocking the cellular type I IFN induction pathway.23 NS3 is one of the key targets for HCV antiviral drug development. NS4A forms a stable complex with NS3 and is a cofactor for NS3 protease. The role of NS4B is not well understood, although it is known to induce the membranous web formation. NS5A is a dimeric zinc-binding metalloprotein which binds the viral RNA and various host factors in close proximity to HCV core and lipid droplets. Inhibitors of HCV NS5A showed antiviral effect in patients and are in rapid clinical development. Finally, NS5B is the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) which is also being actively targeted for antiviral drug development.

Collectively, these proteins also contribute to various aspects of HCV life cycle, including viral attachment, entry and fusion, HCV RNA translation, posttranslational processing, HCV replication, virus assembly and release.

HCV virion and lipoviroparticle

The HCV viral particle includes HCV RNA genome, core and the envelope glycoproteins, E1 and E2.2 HCV RNA genome interacts with the core protein to form the viral nucleocapsid, in association with cytosolic lipid droplets (cLD). The viral nucleocapsid is enveloped in lipid-rich viral envelope with the E1 and E2 glycoproteins that play key roles in virus entry through receptor binding and fusion.24,25 E1/E2 glycoproteins are type I transmembrane glycoproteins that can form non-covalent heterodimers within the infected cells or large covalently linked complexes on the viral particle. They include a large N-terminal ectodomain and a short C-terminal transmembrane domain. The transmembrane domains are involved in membrane anchoring, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) localization, and heterodimerization of the envelope glycoproteins.26-28 E1 and E2 are highly glycosylated, containing up to 6 and 11 glycosylation sites, respectively.29

Hypervariable regions have been identified in the E2 envelope glycoprotein.30 In particular, hypervariable region 1 (HVR1) is a 27 amino acids long segment of basic residues with a high degree of sequence variability as well as highly conserved conformation, suggesting a role as HCV neutralizing epitope and involvement with host entry factor.31-33 HCV virion also associates with various lipoproteins such as apoE, apoB, apoC1, apoC2 and apoC3 to form a complex lipoviroparticle (LVP) and various lipoprotein components can influence HCV entry.34

Viral attachment, entry and fusion

Viral entry into the host cell involves a complex series of interactions including attachment, entry and fusion. The initial viral attachment to its receptor/co-receptors may involve HVR1 in HCV E235,36 with facilitation by heparan sulfate proteoglycans expressed on hepatocyte surface.37-40 While LDL receptors (LDLR) can bind HCV and promote its cellular entry,41 HCV-LDLR interaction may be non-productive and can potentially lead to viral particle degradation.40 Following attachment to the entry factors, HCV is internalized into the target cells via a pH-dependent and clathrin-mediated endocytosis.42-45

Multiple cellular receptors and entry factors for HCV have been identified, including the scavenger receptor class B type I (SRB1),46 and CD8147 as well as tight junction proteins, claudin-1 (CLDN1)48 and occludin (OCLN).49,50 Additional recently identified entry factors include the receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), ephrin receptor A2 (EphA2)51 and Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 cholesterol absorption receptor (NPC1L1).52 The various entry factors are briefly described below:

Scavenger receptor class B type I

The first two HCV entry factors (SRB1 and CD81) were identified as binding partners of HCV E2.46,47 SRB1 is a 509-amino acid multi-ligand glycoprotein receptor which is known to be a major receptor for high-density lipoproteins (HDLs).53 It is highly expressed in the liver and promotes selective uptake of HDL cholesterol esters into hepatocytes.54 A role of SRB1 in HCV entry was first suggested by its binding of HCV E2 through HVR1.46 The lipid transfer activity of SRB1 may be required for HCV cell entry since lipoprotein ligands can modulate HCV/SRB1 interactions with HCV entry enhancement by HDL and inhibition by oxidized LDL.54-57 Of interest, level of SRB1 on hepatocytes can regulate the level of HCV entry and infectivity,58 whereas steroids such as prednisolone can promote HCV entry by up-regulating SRB1 expression.59 Human monoclonal antibody against SRB1 was shown to prevent HCV infection in vitro in hepatocytes and in vivo using chimeric mice engrafted with human hepatocytes.57 In a phase I clinical trial of HCV-infected patients, SRB1 antagonist was shown to inhibit HCV replication with added synergy for other antiviral therapeutics.60

CD81

Human CD81 is a tetraspanin molecule that is broadly expressed and involved in many cellular functions including adhesion, morphology, proliferation and differentiation. It includes 4 transmembrane domains, 2 short intracellular domains and two extracellular loop domains (small and large).54 CD81 is likely involved after the very early phase of HCV entry (i.e. after SRB1), promoting a conformational change in the HCV E1/E2 envelope glycoprotein to facilitate low pH-dependent fusion and viral endocytosis.61 Involvement at a later phase after virus internalization was also suggested recently.62 CD81 large extracellular loop binds HCV through its envelope glycoprotein E2.47,63 The sequence of CD81 large extracellular loop is conserved between humans and chimpanzees, the only 2 species permissive to HCV infection in vivo.64,65 However, CD81 from other species (e.g. African green monkey, tamarin, rats, mice, hamster) can support entry of HCV clones in vitro, suggesting that CD81 polymorphism is not sufficient to define HCV susceptibility.66 Although the ubiquitous expression of CD81 in multiple cell types may limit focused therapeutic application, anti-CD81 was shown to inhibit HCV entry in vivo in chimeric mouse model of HCV replication.67

The tight junction proteins Claudin 1 and Occludin

Two tight junction proteins (CLDN1 and OCLN) identified by screening cDNA library for cellular factors that enable infection by HCV pseudoparticles were shown to be essential entry factors for HCV.48,50 Interestingly, neither CLDN1 nor OCLN seems to interact directly with HCV particles. However, CLDN1 may interact with CD81 as a part of the HCV receptor complex,68,69 it is believed that CLDN1 and OCLN are involved in a later phase of HCV entry, after SRB1 and CD81, although their precise roles are not fully defined. It was also shown that HCV envelope glycoproteins promote coendocytosis of CD81 and CLDN1 in a clathrin- and dynamin-dependent process.62 Finally, anti-CLDN1 monoclonal antibodies were shown to inhibit HCV infection in hepatocytes in vitro by neutralizing the interactions between HCV E2 and CLDN1.70,71

Receptor tyrosine kinases and Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 cholesterol absorption receptor

Two RTKs including the EGFR and EphA2 were recently identified as HCV entry factors by a functional RNAi kinase screen.51 These RTKs appear to participate in HCV entry after the initial attachment/binding step, by regulating CD81 and CLDN1 co-receptor interactions and membrane fusion. RTKs also contributed to cell-cell transmission of HCV. Relevant for clinical application, infection by all major HCV genotypes and escape variants could be inhibited by RTK-specific ligands and antibodies including erlotinib (an EGFR-specific antibody that is FDA-approved for cancer therapy). Finally, a group in Chicago identified NPC1L1 (a cholesterol sensing receptor expressed on apical surface of hepatocytes as well as enterocytes) as a new HCV entry factor, which can be inhibited by an available NPC1L1 antagonist ezetimibe which is FDA-approved to treat hypercholesterolemia.52

Collectively, these receptors and entry factors provide potential avenues to prevent HCV infection and spread, provided that modulation of their physiological role does not lead to significant toxicity.

HCV RNA translation, polyprotein processing and replication

Following target cell entry through receptor-mediated endocytosis, HCV particle undergoes pH-dependent membrane fusion within an acidic endosomal compartment to release its RNA genome into the cytoplasm.19,44,45 HCV polyprotein is translated in rough ER with the positive strand HCV RNA as the template, with the translation initiated in a cap-independent manner via the IRES in the 5'NTR. HCV translation yields a single polyprotein precursor of approximately 3000 amino acid in length, that is further processed by cellular (e.g. signal peptidases) and viral proteases (NS2, NS3/4A) to generate 10 individual viral proteins, including core and envelope glycoproteins, E1 and E2, p7, NS2, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B as mentioned above.

In the course of polyprotein processing, the HCV proteins are seen to be associated with a "membranous web" which includes double-membrane vesicles containing HCV nonstructural proteins, HCV RNA, ER membranes and lipid droplets.19,72,73 The membranous web in HCV-expressing cells appears to be induced by HCV NS4B possibly in combination with NS5A.74,75 Viral RNA replication is believed to occur in these webs with the positive strand RNA genome as a template for the NS5B RdRp to generate the negative strand replicative intermediate, to produce further positive sense genomes. Nascent positive strand RNA genomes can be further translated to produce new viral proteins, or serve as templates for further RNA replication, or be assembled to infectious virions.

Various cellular factors are involved in HCV replication, including cyclophilin A and phosphatidylinositol 4 kinase IIIα (PI4KIIIα). Cyclophilin A can modulate RNA-binding capacity of NS5B polymerase and interact with NS5A. As such, cyclophilin inhibitors have antiviral effect against HCV with clinical development ongoing.76-80 As for PI4KIIIα, it is a lipid kinase that is recruited to the membranous web by NS5A, required for HCV replication and provide integrity to the membranous viral replication complex.81-84

Viral assembly and release

The HCV assembly and release process is not fully understood. However, it appears to be closely linked to lipid metabolism.85 The link between HCV and lipid metabolism was first noted in clinical practice based on fatty changes in liver tissue that was further shown to be associated with HCV core.86 HCV infection induces a profound change in the intracellular distribution of lipid droplets (LDs)87 from generalized cytoplasmic pattern in uninfected cells to accumulation around the perinuclear region in HCV-infected cells associated with viral proteins and genome.88,89 HCV core association with LDs appears to be critical in viral assembly and interventions which block this interaction disrupt virus production.90-92 It is likely that all other viral proteins play a key role in the assembly process, centering around the lipid droplets where assembly is triggered in the membranous and lipid-rich environment by the structural HCV proteins (core/E1/E2/p7/NS2) and the replication complex. The very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion pathway is closely related to that of assembled virions.93,94 The virion is a lipoviroparticle with a lipid composition that resembles VLDL and LDL with associated apoE and/or apoB, which are essential for the infectious virus assembly.93-96 Of clinical relevance, histological fatty changes in the liver has been associated with clinical and therapeutic outcomes97 and HCV genotype 3 was shown to mediate greater steatosis,98 although its pathogenetic mechanisms related to HCV life cycle is not clear. It is also notable that HCV replication can be controlled through cholesterol biosynthetic pathway and lipid-lowering drugs can suppress HCV replication in vitro.99,100

CONCLUSION

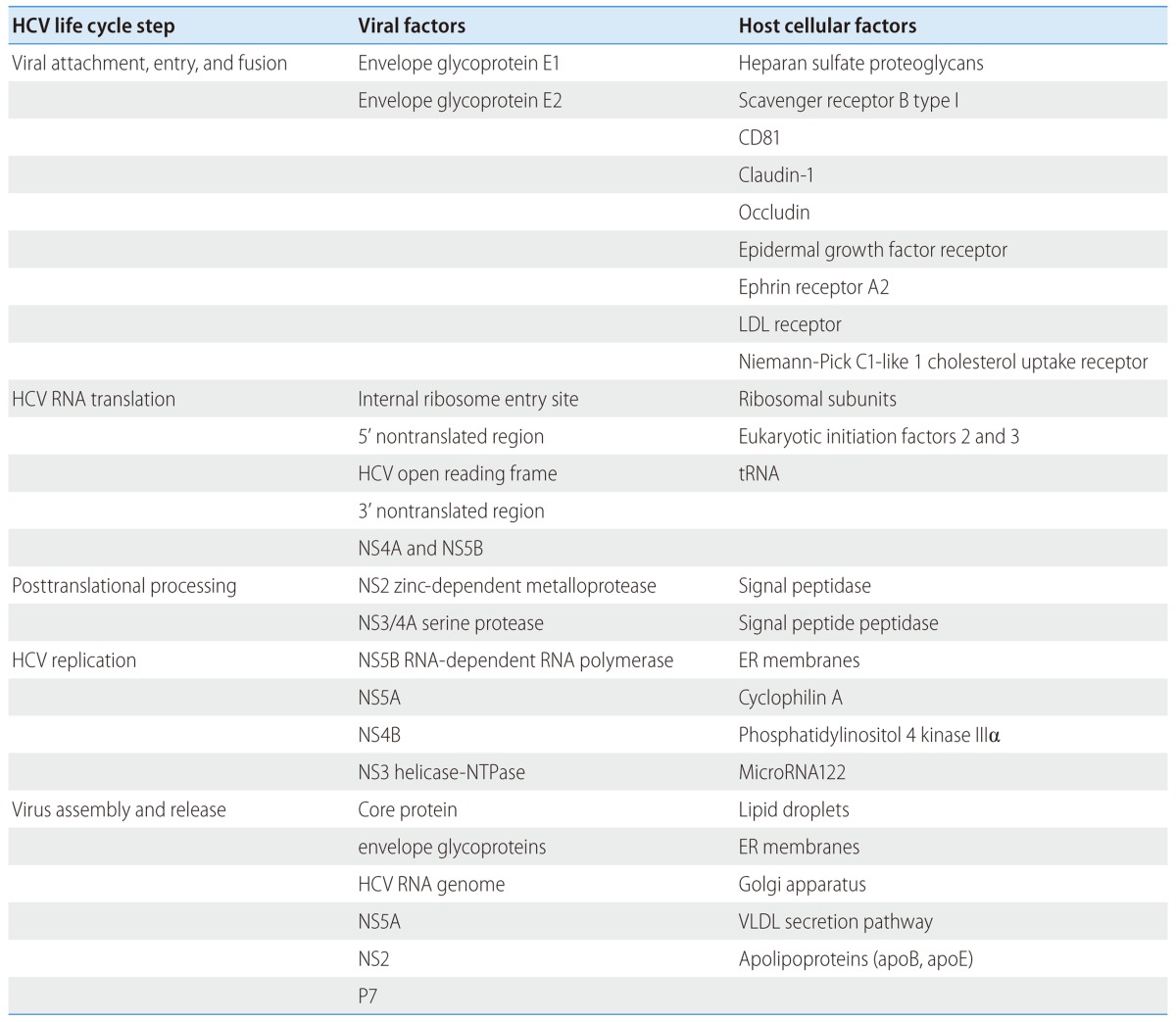

Since its initial cloning of HCV, we have gained considerable knowledge about HCV life cycle including entry, translation, replication and host cellular interactions (Table 1).101 These advances have also been critical in antiviral drug development for patients with chronic hepatitis C. After many years, we are now close to being able to cure our patients with potent, pan-genotypic, cost-effective and less toxic therapeutic regimen to prevent their progression to cirrhosis and liver cancer. Remaining challenges include the development of prophylactic vaccine for world-wide application (including countries without sufficient economic development or access to newly developed antivirals) and better understanding of the mechanisms of persistence and pathogenesis of this fascinating virus.

Table 1.

Putative viral and host cellular factors interacting in HCV life cycle (Adapted from Pawlotsky JM, et al. Gastroenterology 2007;132:1979-1998)101

Abbreviations

- cLD

cytosolic lipid droplets

- CLDN1

claudin-1

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- eIF

eukaryotic initiation factor

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- EphA2

ephrin receptor A2

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HDLs

high-density lipoproteins

- HVR1

hypervariable region 1

- IFN

interferon

- IRES

internal ribosome entry site

- LDs

lipid droplets

- LDLR

low density lipoprotein receptor

- LVP

lipoviroparticle

- NTR

nontranslated region

- NPC1L1

Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 cholesterol absorption receptor

- OCLN

occludin

- PEG IFN

pegylated interferon alpha

- PI4KIIIα

phosphatidylinositol 4 kinase IIIα

- RdRp

RNA-dependent RNA polymerase

- riba

ribavirin

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinases

- SRB1

scavenger receptor class B type I

- SVR

sustained virological response

- VLDL

very low density lipoprotein

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Choo QL, Kuo G, Weiner AJ, Overby LR, Bradley DW, Houghton M. Isolation of a cDNA clone derived from a blood-borne non-A, non-B viral hepatitis genome. Science. 1989;244:359–362. doi: 10.1126/science.2523562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartenschlager R, Penin F, Lohmann V, Andre P. Assembly of infectious hepatitis C virus particles. Trends Microbiol. 2011;19:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alter HJ, Seeff LB. Recovery, persistence, and sequelae in hepatitis C virus infection: a perspective on long-term outcome. Semin Liver Dis. 2000;20:17–35. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Management of hepatitis C: 2002--June 10-12, 2002. Hepatology. 2002;36(Suppl 1):S3–S20. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.37117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McHutchison JG, Everson GT, Gordon SC, Jacobson IM, Sulkowski M, Kauffman R, et al. Telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1827–1838. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, Di Bisceglie AM, Reddy KR, Bzowej NH, et al. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2405–2416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwo PY, Lawitz EJ, McCone J, Schiff ER, Vierling JM, Pound D, et al. Efficacy of boceprevir, an NS3 protease inhibitor, in combination with peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C infection (SPRINT-1): an open-label, randomised, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2010;376:705–716. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60934-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poordad F, McCone J, Jr, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1195–1206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ploss A, Dubuisson J. New advances in the molecular biology of hepatitis C virus infection: towards the identification of new treatment targets. Gut. 2012;61(Suppl 1):i25–i35. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumann AU, Lam NP, Dahari H, Gretch DR, Wiley TE, Layden TJ, et al. Hepatitis C viral dynamics in vivo and the antiviral efficacy of interferon-alpha therapy. Science. 1998;282:103–107. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5386.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Francesco R, Migliaccio G. Challenges and successes in developing new therapies for hepatitis C. Nature. 2005;436:953–960. doi: 10.1038/nature04080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simmonds P, Bukh J, Combet C, Deleage G, Enomoto N, Feinstone S, et al. Consensus proposals for a unified system of nomenclature of hepatitis C virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2005;42:962–973. doi: 10.1002/hep.20819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown EA, Zhang H, Ping LH, Lemon SM. Secondary structure of the 5' nontranslated regions of hepatitis C virus and pestivirus genomic RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5041–5045. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.19.5041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang C, Le SY, Ali N, Siddiqui A. An RNA pseudoknot is an essential structural element of the internal ribosome entry site located within the hepatitis C virus 5' noncoding region. RNA. 1995;1:526–537. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honda M, Ping LH, Rijnbrand RC, Amphlett E, Clarke B, Rowlands D, et al. Structural requirements for initiation of translation by internal ribosome entry within genome-length hepatitis C virus RNA. Virology. 1996;222:31–42. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lukavsky PJ, Otto GA, Lancaster AM, Sarnow P, Puglisi JD. Structures of two RNA domains essential for hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site function. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1105–1110. doi: 10.1038/81951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji H, Fraser CS, Yu Y, Leary J, Doudna JA. Coordinated assembly of human translation initiation complexes by the hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16990–16995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407402101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otto GA, Puglisi JD. The pathway of HCV IRES-mediated translation initiation. Cell. 2004;119:369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alvisi G, Madan V, Bartenschlager R. Hepatitis C virus and host cell lipids: an intimate connection. RNA Biol. 2011;8:258–269. doi: 10.4161/rna.8.2.15011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan DE, Sugimoto K, Newton K, Valiga ME, Ikeda F, Aytaman A, et al. Discordant role of CD4 T-cell response relative to neutralizing antibody and CD8 T-cell responses in acute hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:654–666. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Logvinoff C, Major ME, Oldach D, Heyward S, Talal A, Balfe P, et al. Neutralizing antibody response during acute and chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10149–10154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403519101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Hahn T, Yoon JC, Alter H, Rice CM, Rehermann B, Balfe P, et al. Hepatitis C virus continuously escapes from neutralizing antibody and T-cell responses during chronic infection in vivo. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:667–678. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia-Sastre A, Biron CA. Type 1 interferons and the virus-host relationship: a lesson in detente. Science. 2006;312:879–882. doi: 10.1126/science.1125676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartosch B, Dubuisson J, Cosset FL. Infectious hepatitis C virus pseudo-particles containing functional E1-E2 envelope protein complexes. J Exp Med. 2003;197:633–642. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielsen SU, Bassendine MF, Burt AD, Bevitt DJ, Toms GL. Characterization of the genome and structural proteins of hepatitis C virus resolved from infected human liver. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:1497–1507. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79967-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deleersnyder V, Pillez A, Wychowski C, Blight K, Xu J, Hahn YS, et al. Formation of native hepatitis C virus glycoprotein complexes. J Virol. 1997;71:697–704. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.697-704.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cocquerel L, Meunier JC, Pillez A, Wychowski C, Dubuisson J. A retention signal necessary and sufficient for endoplasmic reticulum localization maps to the transmembrane domain of hepatitis C virus glycoprotein E2. J Virol. 1998;72:2183–2191. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2183-2191.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cocquerel L, Wychowski C, Minner F, Penin F, Dubuisson J. Charged residues in the transmembrane domains of hepatitis C virus glycoproteins play a major role in the processing, subcellular localization, and assembly of these envelope proteins. J Virol. 2000;74:3623–3633. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.8.3623-3633.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lavie M, Goffard A, Dubuisson J. HCV Glycoproteins: Assembly of a Functional E1-E2 Heterodimer. In: Tan SL, editor. Hepatitis C Viruses: Genomes and Molecular Biology. Norfolk: Horizon Bioscience; 2006. pp. 121–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiner AJ, Christopherson C, Hall JE, Bonino F, Saracco G, Brunetto MR, et al. Sequence variation in hepatitis C viral isolates. J Hepatol. 1991;13(Suppl 4):S6–S14. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farci P, Shimoda A, Wong D, Cabezon T, De Gioannis D, Strazzera A, et al. Prevention of hepatitis C virus infection in chimpanzees by hyperimmune serum against the hypervariable region 1 of the envelope 2 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:15394–15399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zibert A, Kraas W, Meisel H, Jung G, Roggendorf M. Epitope mapping of antibodies directed against hypervariable region 1 in acute self-limiting and chronic infections due to hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 1997;71:4123–4127. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.4123-4127.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penin F, Combet C, Germanidis G, Frainais PO, Deleage G, Pawlotsky JM. Conservation of the conformation and positive charges of hepatitis C virus E2 envelope glycoprotein hypervariable region 1 points to a role in cell attachment. J Virol. 2001;75:5703–5710. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.12.5703-5710.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andre P, Komurian-Pradel F, Deforges S, Perret M, Berland JL, Sodoyer M, et al. Characterization of low- and very-low-density hepatitis C virus RNA-containing particles. J Virol. 2002;76:6919–6928. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.6919-6928.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flint M, McKeating JA. The role of the hepatitis C virus glycoproteins in infection. Rev Med Virol. 2000;10:101–117. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1654(200003/04)10:2<101::aid-rmv268>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosa D, Campagnoli S, Moretto C, Guenzi E, Cousens L, Chin M, et al. A quantitative test to estimate neutralizing antibodies to the hepatitis C virus: cytofluorimetric assessment of envelope glycoprotein 2 binding to target cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:1759–1763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barth H, Schafer C, Adah MI, Zhang F, Linhardt RJ, Toyoda H, et al. Cellular binding of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein E2 requires cell surface heparan sulfate. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41003–41012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Molina S, Castet V, Fournier-Wirth C, Pichard-Garcia L, Avner R, Harats D, et al. The low-density lipoprotein receptor plays a role in the infection of primary human hepatocytes by hepatitis C virus. J Hepatol. 2007;46:411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Owen DM, Huang H, Ye J, Gale M., Jr Apolipoprotein E on hepatitis C virion facilitates infection through interaction with low-density lipoprotein receptor. Virology. 2009;394:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Albecka A, Belouzard S, Op de Beeck A, Descamps V, Goueslain L, Bertrand-Michel J, et al. Role of low-density lipoprotein receptor in the hepatitis C virus life cycle. Hepatology. 2012;55:998–1007. doi: 10.1002/hep.25501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agnello V, Abel G, Elfahal M, Knight GB, Zhang QX. Hepatitis C virus and other flaviviridae viruses enter cells via low density lipoprotein receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:12766–12771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.22.12766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bartosch B, Vitelli A, Granier C, Goujon C, Dubuisson J, Pascale S, et al. Cell entry of hepatitis C virus requires a set of co-receptors that include the CD81 tetraspanin and the SR-B1 scavenger receptor. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41624–41630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hsu M, Zhang J, Flint M, Logvinoff C, Cheng-Mayer C, Rice CM, et al. Hepatitis C virus glycoproteins mediate pH-dependent cell entry of pseudotyped retroviral particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7271–7276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832180100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tscherne DM, Jones CT, Evans MJ, Lindenbach BD, McKeating JA, Rice CM. Time- and temperature-dependent activation of hepatitis C virus for low-pH-triggered entry. J Virol. 2006;80:1734–1741. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1734-1741.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blanchard E, Belouzard S, Goueslain L, Wakita T, Dubuisson J, Wychowski C, et al. Hepatitis C virus entry depends on clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J Virol. 2006;80:6964–6972. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00024-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scarselli E, Ansuini H, Cerino R, Roccasecca RM, Acali S, Filocamo G, et al. The human scavenger receptor class B type I is a novel candidate receptor for the hepatitis C virus. EMBO J. 2002;21:5017–5025. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pileri P, Uematsu Y, Campagnoli S, Galli G, Falugi F, Petracca R, et al. Binding of hepatitis C virus to CD81. Science. 1998;282:938–941. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5390.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Evans MJ, von Hahn T, Tscherne DM, Syder AJ, Panis M, Wolk B, et al. Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus co-receptor required for a late step in entry. Nature. 2007;446:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nature05654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu S, Yang W, Shen L, Turner JR, Coyne CB, Wang T. Tight junction proteins claudin-1 and occludin control hepatitis C virus entry and are downregulated during infection to prevent superinfection. J Virol. 2009;83:2011–2014. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01888-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ploss A, Evans MJ, Gaysinskaya VA, Panis M, You H, de Jong YP, et al. Human occludin is a hepatitis C virus entry factor required for infection of mouse cells. Nature. 2009;457:882–886. doi: 10.1038/nature07684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lupberger J, Zeisel MB, Xiao F, Thumann C, Fofana I, Zona L, et al. EGFR and EphA2 are host factors for hepatitis C virus entry and possible targets for antiviral therapy. Nat Med. 2011;17:589–595. doi: 10.1038/nm.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sainz B, Jr, Barretto N, Martin DN, Hiraga N, Imamura M, Hussain S, et al. Identification of the Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 cholesterol absorption receptor as a new hepatitis C virus entry factor. Nat Med. 2012;18:281–285. doi: 10.1038/nm.2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Acton S, Rigotti A, Landschulz KT, Xu S, Hobbs HH, Krieger M. Identification of scavenger receptor SR-BI as a high density lipoprotein receptor. Science. 1996;271:518–520. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meredith LW, Wilson GK, Fletcher NF, McKeating JA. Hepatitis C virus entry: beyond receptors. Rev Med Virol. 2012;22:182–193. doi: 10.1002/rmv.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dreux M, Dao Thi VL, Fresquet J, Guerin M, Julia Z, Verney G, et al. Receptor complementation and mutagenesis reveal SR-BI as an essential HCV entry factor and functionally imply its intra- and extracellular domains. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000310. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dorner M, Horwitz JA, Robbins JB, Barry WT, Feng Q, Mu K, et al. A genetically humanized mouse model for hepatitis C virus infection. Nature. 2011;474:208–211. doi: 10.1038/nature10168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meuleman P, Catanese MT, Verhoye L, Desombere I, Farhoudi A, Jones CT, et al. A human monoclonal antibody targeting scavenger receptor class B type I precludes hepatitis C virus infection and viral spread in vitro and in vivo. Hepatology. 2012;55:364–372. doi: 10.1002/hep.24692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grove J, Huby T, Stamataki Z, Vanwolleghem T, Meuleman P, Farquhar M, et al. Scavenger receptor BI and BII expression levels modulate hepatitis C virus infectivity. J Virol. 2007;81:3162–3169. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02356-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ciesek S, Steinmann E, Iken M, Ott M, Helfritz FA, Wappler I, et al. Glucocorticosteroids increase cell entry by hepatitis C virus. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1875–1884. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu H, Wong-Staal F, Lee H, Syder A, McKelvy J, Schooley RT, et al. Evaluation of ITX 5061, a scavenger receptor B1 antagonist: resistance selection and activity in combination with other hepatitis C virus antivirals. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:656–662. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sharma NR, Mateu G, Dreux M, Grakoui A, Cosset FL, Melikyan GB. Hepatitis C virus is primed by CD81 protein for low pH-dependent fusion. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:30361–30376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.263350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Farquhar MJ, Hu K, Harris HJ, Davis C, Brimacombe CL, Fletcher SJ, et al. Hepatitis C virus induces CD81 and claudin-1 endocytosis. J Virol. 2012;86:4305–4316. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06996-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Petracca R, Falugi F, Galli G, Norais N, Rosa D, Campagnoli S, et al. Structure-function analysis of hepatitis C virus envelope-CD81 binding. J Virol. 2000;74:4824–4830. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4824-4830.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Major ME, Dahari H, Mihalik K, Puig M, Rice CM, Neumann AU, et al. Hepatitis C virus kinetics and host responses associated with disease and outcome of infection in chimpanzees. Hepatology. 2004;39:1709–1720. doi: 10.1002/hep.20239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bartosch B, Dubuisson J. Recent advances in hepatitis C virus cell entry. Viruses. 2010;2:692–709. doi: 10.3390/v2030692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Flint M, von Hahn T, Zhang J, Farquhar M, Jones CT, Balfe P, et al. Diverse CD81 proteins support hepatitis C virus infection. J Virol. 2006;80:11331–11342. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00104-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Meuleman P, Hesselgesser J, Paulson M, Vanwolleghem T, Desombere I, Reiser H, et al. Anti-CD81 antibodies can prevent a hepatitis C virus infection in vivo. Hepatology. 2008;48:1761–1768. doi: 10.1002/hep.22547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harris HJ, Farquhar MJ, Mee CJ, Davis C, Reynolds GM, Jennings A, et al. CD81 and claudin 1 coreceptor association: role in hepatitis C virus entry. J Virol. 2008;82:5007–5020. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02286-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harris HJ, Davis C, Mullins JG, Hu K, Goodall M, Farquhar MJ, et al. Claudin association with CD81 defines hepatitis C virus entry. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:21092–21102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.104836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fofana I, Krieger SE, Grunert F, Glauben S, Xiao F, Fafi-Kremer S, et al. Monoclonal anti-claudin 1 antibodies prevent hepatitis C virus infection of primary human hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:953–964. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Krieger SE, Zeisel MB, Davis C, Thumann C, Harris HJ, Schnober EK, et al. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus infection by anti-claudin-1 antibodies is mediated by neutralization of E2-CD81-claudin-1 associations. Hepatology. 2010;51:1144–1157. doi: 10.1002/hep.23445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Egger D, Wolk B, Gosert R, Bianchi L, Blum HE, Moradpour D, et al. Expression of hepatitis C virus proteins induces distinct membrane alterations including a candidate viral replication complex. J Virol. 2002;76:5974–5984. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.5974-5984.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gosert R, Egger D, Lohmann V, Bartenschlager R, Blum HE, Bienz K, et al. Identification of the hepatitis C virus RNA replication complex in Huh-7 cells harboring subgenomic replicons. J Virol. 2003;77:5487–5492. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5487-5492.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bartenschlager R, Cosset FL, Lohmann V. Hepatitis C virus replication cycle. J Hepatol. 2010;53:583–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Romero-Brey I, Merz A, Chiramel A, Lee JY, Chlanda P, Haselman U, et al. Three-dimensional architecture and biogenesis of membrane structures associated with hepatitis C virus replication. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003056. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang F, Robotham JM, Nelson HB, Irsigler A, Kenworthy R, Tang H. Cyclophilin A is an essential cofactor for hepatitis C virus infection and the principal mediator of cyclosporine resistance in vitro. J Virol. 2008;82:5269–5278. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02614-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kaul A, Stauffer S, Berger C, Pertel T, Schmitt J, Kallis S, et al. Essential role of cyclophilin A for hepatitis C virus replication and virus production and possible link to polyprotein cleavage kinetics. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000546. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Coelmont L, Hanoulle X, Chatterji U, Berger C, Snoeck J, Bobardt M, et al. DEB025 (Alisporivir) inhibits hepatitis C virus replication by preventing a cyclophilin A induced cis-trans isomerisation in domain II of NS5A. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fernandes F, Ansari IU, Striker R. Cyclosporine inhibits a direct interaction between cyclophilins and hepatitis C NS5A. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9815. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Foster TL, Gallay P, Stonehouse NJ, Harris M. Cyclophilin A interacts with domain II of hepatitis C virus NS5A and stimulates RNA binding in an isomerase-dependent manner. J Virol. 2011;85:7460–7464. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00393-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Berger KL, Cooper JD, Heaton NS, Yoon R, Oakland TE, Jordan TX, et al. Roles for endocytic trafficking and phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase III alpha in hepatitis C virus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7577–7582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902693106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Borawski J, Troke P, Puyang X, Gibaja V, Zhao S, Mickanin C, et al. Class III phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase alpha and beta are novel host factor regulators of hepatitis C virus replication. J Virol. 2009;83:10058–10074. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02418-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Trotard M, Lepere-Douard C, Regeard M, Piquet-Pellorce C, Lavillette D, Cosset FL, et al. Kinases required in hepatitis C virus entry and replication highlighted by small interference RNA screening. FASEB J. 2009;23:3780–3789. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-131920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Reiss S, Rebhan I, Backes P, Romero-Brey I, Erfle H, Matula P, et al. Recruitment and activation of a lipid kinase by hepatitis C virus NS5A is essential for integrity of the membranous replication compartment. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:32–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Targett-Adams P, Boulant S, Douglas MW, McLauchlan J. Lipid metabolism and HCV infection. Viruses. 2010;2:1195–1217. doi: 10.3390/v2051195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Barba G, Harper F, Harada T, Kohara M, Goulinet S, Matsuura Y, et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein shows a cytoplasmic localization and associates to cellular lipid storage droplets. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:1200–1205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McLauchlan J. Lipid droplets and hepatitis C virus infection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:552–559. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Olofsson SO, Bostrom P, Andersson L, Rutberg M, Levin M, Perman J, et al. Triglyceride containing lipid droplets and lipid dropletassociated proteins. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2008;19:441–447. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e32830dd09b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Popescu CI, Rouille Y, Dubuisson J. Hepatitis C virus assembly imaging. Viruses. 2011;3:2238–2254. doi: 10.3390/v3112238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Targett-Adams P, Hope G, Boulant S, McLauchlan J. Maturation of hepatitis C virus core protein by signal peptide peptidase is required for virus production. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:16850–16859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Boulant S, Douglas MW, Moody L, Budkowska A, Targett-Adams P, McLauchlan J. Hepatitis C virus core protein induces lipid droplet redistribution in a microtubule- and dynein-dependent manner. Traffic. 2008;9:1268–1282. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Miyanari Y, Atsuzawa K, Usuda N, Watashi K, Hishiki T, Zayas M, et al. The lipid droplet is an important organelle for hepatitis C virus production. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1089–1097. doi: 10.1038/ncb1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Huang H, Sun F, Owen DM, Li W, Chen Y, Gale M, Jr, et al. Hepatitis C virus production by human hepatocytes dependent on assembly and secretion of very low-density lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:5848–5853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700760104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gastaminza P, Cheng G, Wieland S, Zhong J, Liao W, Chisari FV. Cellular determinants of hepatitis C virus assembly, maturation, degradation, and secretion. J Virol. 2008;82:2120–2129. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02053-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chang KS, Jiang J, Cai Z, Luo G. Human apolipoprotein e is required for infectivity and production of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. J Virol. 2007;81:13783–13793. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01091-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Merz A, Long G, Hiet MS, Brugger B, Chlanda P, Andre P, et al. Biochemical and morphological properties of hepatitis C virus particles and determination of their lipidome. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:3018–3032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.175018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Patton HM, Patel K, Behling C, Bylund D, Blatt LM, Vallee M, et al. The impact of steatosis on disease progression and early and sustained treatment response in chronic hepatitis C patients. J Hepatol. 2004;40:484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kumar D, Farrell GC, Fung C, George J. Hepatitis C virus genotype 3 is cytopathic to hepatocytes: Reversal of hepatic steatosis after sustained therapeutic response. Hepatology. 2002;36:1266–1272. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim SS, Peng LF, Lin W, Choe WH, Sakamoto N, Kato N, et al. A cell-based, high-throughput screen for small molecule regulators of hepatitis C virus replication. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:311–320. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kapadia SB, Chisari FV. Hepatitis C virus RNA replication is regulated by host geranylgeranylation and fatty acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2561–2566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409834102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pawlotsky JM, Chevaliez S, McHutchison JG. The hepatitis C virus life cycle as a target for new antiviral therapies. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1979–1998. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]