Abstract

Background and Purpose

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play a crucial role in recognizing invading pathogens and endogenous danger signal to induce immune and inflammatory responses. Since dysregulation of TLRs enhances the risk of immune disorders and chronic inflammatory diseases, modulation of TLR activity by phytochemicals could be useful therapeutically. We investigated the effect of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) on TLR-mediated inflammation and the underlying regulatory mechanism.

Experimental Approach

Inhibitory effects of CAPE on TLR4 activation were assessed with in vivo murine skin inflammation model and in vitro production of inflammatory mediators in macrophages. In vitro binding assay, cell-based immunoprecipitation study and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis were performed to determine lipopolysaccharide (LPS) binding to MD2 and to identify the direct binding site of CAPE in MD2.

Key Results

Topical application of CAPE attenuated dermal inflammation and oedema induced by intradermal injection of LPS (a TLR4 agonist). CAPE suppressed production of inflammatory mediators and activation of NFκB and interferon-regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) in macrophages stimulated with LPS. CAPE interrupted LPS binding to MD2 through formation of adduct specifically with Cys133 located in hydrophobic pocket of MD2. The inhibitory effect on LPS-induced IRF3 activation by CAPE was not observed when 293T cells were reconstituted with MD2 (C133S) mutant.

Conclusions and Implications

Our results show a novel mechanism for anti-inflammatory activity of CAPE to prevent TLR4 activation by interfering with interaction between ligand (LPS) and receptor complex (TLR4/MD2). These further provide beneficial information for the development of therapeutic strategies to prevent chronic inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Toll-like receptor, caffeic acid phenethyl ester, LPS, MD2, cysteine133

Introduction

Toll-like receptors (TLRs), as one of the pattern recognition receptors, play critical roles in host defence by sensing conserved molecular patterns on microbial pathogens and mounting immune responses (Akira et al., 2006). TLRs are type I transmembrane receptors with an ectodomain containing leucine-rich repeat motifs, a transmembrane domain and a cytosolic Toll/interleukin-1 receptor homology domain. TLR4 is the first characterized TLR and responsible for gram-negative bacteria-induced sepsis by recognizing lipopolysaccaride (LPS), a cell wall component of gram-negative bacteria (Poltorak et al., 1998). Recognition of LPS by TLR4 requires MD2 since most of lipid chains of LPS interact with a hydrophobic pocket in MD2 (Park et al., 2009). MD2 is a glycoprotein and forms a complex with TLR4 when expressed on the cell surface. Engagement of LPS with TLR4/MD2 complex triggers dimerization of two TLR4/MD2 complexes (Park et al., 2009), which leads to the recruitment of two major adaptor molecules, myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) and TIR-domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon-beta (TRIF), and the activation of intracellular signalling pathways for the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. MyD88 is an adaptor molecule common to most TLRs. It mediates the activation of TNF receptor-associated factor 6 and IKKβ complex, which results in activation of transcription factors, NFκB and AP-1, due to phosphorylation and degradation of IκB proteins, and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases respectively (Kawai et al., 1999). TRIF causes phosphorylation and activation of interferon-regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) and the subsequent expression of type I interferons (IFNs) and IFN-inducible genes via TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and IKKε (Fitzgerald et al., 2003; Oshiumi et al., 2003). TRIF also activates NFκB in a late-phase through receptor-interacting protein 1 (RIP1) (Meylan et al., 2004).

Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) is an active phenolic compound found in natural products such as propolis. It has been reported to have beneficial effects on inflammation and cancer (Frenkel et al., 1993; Michaluart et al., 1999). Intraperitoneal injection of CAPE greatly increased the survival rate of mice in a model of LPS-induced septic shock and also reduced serum levels of TNF-α and nitrite (Jung et al., 2008). Administration of CAPE protected lung from LPS-induced injury in rats (Koksel et al., 2006). In addition, interleukin 12 (IL-12) production and NFκB activation induced by LPS, were inhibited by CAPE in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (Wang et al., 2009). These studies suggest that CAPE is able to modulate activation of TLR4 and that NFκB activation is a common outcome of inhibitory effects of CAPE. However, the details of how CAPE regulates TLR4 remain unclear.

Deregulation of TLR-mediated immune responses can lead to various inflammatory diseases including atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes and cancer (Lee and Hwang, 2006; Keogh and Parker, 2011). Accordingly, pharmacological regulation of TLR activation can be beneficial for immune-related diseases (Kanzler et al., 2007). We therefore investigated the mode of action of CAPE in TLR4 signalling. We found that CAPE attenuated the inflammatory symptoms in LPS-induced skin inflammation animal model and consistently reduced the expression of various inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in macrophages stimulated with LPS. It also inhibited LPS-induced activation of NFκB and IRF3, which are two major transcription factors implicated in TLR4 signalling. Finally, we demonstrated that it prevented the engagement of LPS to TLR4/MD2 complex by formation of adduct with Cys133 in a hydrophobic pocket of MD2, thereby impairing downstream signal activation. These findings indicate that the interaction between LPS and TLR4/MD2 complex is a novel target for anti-inflammatory agents such as CAPE.

Methods

Animals and cell culture

C57BL/6 mice, aged 8–9 weeks (Damul Science, Daejeon, Korea) and BALB/c male mice aged 6–8 weeks (Orient Bio, Seoul, Korea) were acclimated under specific pathogen-free conditions in an animal facility for at least 1 week before use. The mice were housed in a temperature (23 ± 3°C) and relative humidity (40–60%) controlled room. Animal care and the experimental procedures were approved by Amorepacific R&D Center's Committee on the Ethical Use of Animals (IACUC12-347-CJG-059). Bone marrow cells were isolated from C57BL/6 mice and differentiated to macrophages as described previously (Lee et al., 2009). Bone marrow cells were cultured in DMEM (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) containing 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated FBS (Hyclone), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM Hepes buffer and 20% L929 cell-conditioned medium for 6 days, and adherent cells were used as macrophages. RAW264.7 cells (murine monocyte-macrophage cell line, ATCC TIB-71) and 293T cells (human embryonic kidney cells) were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units mL−1 penicillin and 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin (Hyclone). Ba/F3 cells, an IL-3-dependent murine pro-B cell line expressing TLR4, Flag-MD2 and NFκB-luciferase reporter gene were cultured in RPMI1640 medium containing murine IL-3, 10% FBS, 100 units mL−1 penicillin and 100 μg mL−1 streptomycin (Saitoh et al., 2004). Cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2/air environment. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

Reagents and plasmids

CAPE was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Purified LPS from Escherichia coli was obtained from List Biological Laboratory Inc. (Campbell, CA, USA) and dissolved in endotoxin-free water. Biotin-labelled LPS was purchased from Invivogen (San Diego, CA, USA). Anti-flag antibody was from Sigma-Aldrich. All other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise specified.

A constitutively active chimeric CD4-TLR4 was obtained from Dr. Charles Janeway, Jr. (Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA). The expression plasmids for human TRIF and TBK1 and the IFN-β PRDIII-I-luciferase plasmid were kind gifts from Dr. Katherine Fitzgerald (University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, USA). The NFκB (2x)-luciferase reporter construct was provided by Dr. Frank Mercurio (Signal Pharmaceuticals, San Diego, CA, USA). The heat shock protein 70-β-galactosidase plasmid was obtained from Dr. Robert Modlin (University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA), and the expression plasmid for MyD88 was provided by Dr. Jurg Tschopp (University of Lausanne, Switzerland). The expression plasmid for TLR4 was obtained from Addgene (the original provider is Dr. Doug Golenbock). The expression plasmids for wild-type (WT) MD2 and C133S mutant MD2 were obtained from Dr. David Segal (NIH/NCI, USA). All the DNA constructs were prepared on a large scale using an Endofree Plasmid Maxi kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) for transfection.

In vivo skin inflammation experiment in mice

This was performed as previously described (Youn et al., 2010). Briefly, CAPE (1%) or vehicle (100% acetone) was topically treated on the ear of male BALB/c mice at 48, 24 and 1 h before and 6 h after intradermal injection of LPS (50 μg/25 μL in PBS) on the ear. Indomethacin (0.5%) was applied 0.5 h before and 6 h after LPS injection. Twenty-four hours after LPS injection, 6 mm biopsies of injected ear were collected and weighed for the evaluation of LPS-induced inflammation and oedema. Biopsy tissues were processed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological examination by a histologist who was blind to the treatment group.

Cytokine measurement using ELISA

Levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-β, IP-10 and RANTES in culture media were determined using ELISA kits for each cytokine (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The concentration ranges for the standard curves were from 23.4 to 1500, 7.8 to 500, 15.6 to 1000, 31.2 to 2000 and 7.8 to 500 pg mL−1 for TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-β, IP-10, and RANTES respectively. The minimum detectable doses of RANTES and TNF-α were typically less than 2 and 5.1 pg mL−1 respectively. Those of IP-10 and IL-6 were 2.2 and 1.6 pg mL−1 respectively.

Reverse transcription and PCR analysis

This was performed as previously described (Joung et al., 2011). Total RNAs were isolated with Welprep™ reagent (Jeil Biotechservices Inc., Daegu, Korea). RNAs were reverse-transcribed with ImProm-II™ Reverse Transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and amplified with IQ™ SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) for quantitative real-time PCR using an IQ5 (Bio-Rad). Primers were: Tnf-α, 5′-AAAATTCGAGTGACAAGCCTGTAG-3′ and 5′-CCCTTGAAGAGAACCTGGGAGTAG-3′; Il-6, 5′-TTCCTCTCTGCAAGAGACT-3′ and 5′-TGTATCTCTCTGAAGGACT-3′; Ifn-β, 5′-TCCAAGAAAGGACGAACATTCG-3′ and 5′-TGAGGACATCTCCCACGTCAA-3′; Ip-10, 5′-TCCTGCTGGGTCTGAGTG-3′ and 5′-ATTCTTGATGGTCTTAGATTCCG-3′; Rantes, 5′-GCCCACGTCAAGGAGTATTTCTAC-3′ and 5′-AGGACTAGAGCAAGCGATGACAG-3′; β-actin, 5′-TCATGAAGTGTGACGTTGACATCCGT-3′ and 5′-TTGCGGTGCACGATGGAGGGGCCGGA-3′. The specificity of the amplified PCR products was assessed by a melting curve analysis.

Transfection and luciferase assay

RAW264.7 or 293T cells were co-transfected with various plasmids together with the β-galactosidase plasmid using SuperFect Transfection Reagent (Qiagen). Luciferase and β-galactosidase enzyme activities were determined using the Luciferase Assay System and β-galactosidase Enzyme System (Promega). Luciferase activity was normalized by β-galactosidase activity to determine relative luciferase activity.

In vitro assay for LPS binding to MD2

A 96-well microplate was coated overnight at 4°C with polyclonal anti-human MD2 antibody (Abnova, Taipei, Taiwan) in 50 mM Na2CO3 in buffer (pH 9.6). The plate was washed with PBS and blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Recombinant human MD2 (0.1 μM per well; R&D Systems) in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5) was added to a precoated plate and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. CAPE was incubated with MD2 for 1 h at 37°C. For N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) and dithiothreitol (DTT) experiment, CAPE was pre-incubated with NAC (50 μM) or DTT (50 μM) for 30 min at 37°C and then further incubated with rMD2 for 30 min at 37°C. After washing with PBS, biotin-labelled LPS was incubated for 30 min at room temperature and then streptavidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was added for 1.5 h at 37°C. The activity of horseradish peroxidase was determined using EzWay™ TMBsubstrate kit (Koma Biotech, Seoul, Korea). Optical density of each well was measured at 450 nm.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting

To measure LPS binding to MD2, biotin-labelled LPS was incubated with Ba/F3 cells expressing TLR4 and Flag-MD2. Protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-flag antibody and protein A/G PLUS-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) overnight at 4°C on a rocker. Immune complexes were solubilized with Laemmli sample buffer after washing three times. The solubilized proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were probed with primary antibody as indicated, and secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. Streptavidin conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Zymed, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to detect biotin-LPS. Reactive bands were visualized with the ECL system (Amersham Bioscience, Piscataway, NJ, USA).

Immunostaining and confocal imaging

Bone marrow-derived primary macrophages were grown on glass cover slips (18-mm diameter; Marienfeld Laboratory Glassware, Lauda-Königshofen, Germany). After 1 h of pre-treatment with CAPE, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 594® conjugated with LPS (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, OR, USA). The cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde, washed three times with PBS and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin for 50 min. They were then incubated with anti-MD2 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Sigma-Aldrich, and mounted with anti-fade solution (Molecular Probes Inc.). The slides were examined with an LSM710 confocal laser scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) equipped with 40X objectives. Images were obtained with ZEN2011 software (Carl Zeiss).

In-solution digestion and micro liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis

Purified mouse MD2 was obtained from Dr. J. O. Lee (KAIST, Korea) (Park et al., 2009) and 1 μg of protein was incubated with CAPE (20 μM) for 1 h at 37°C. In-solution digestion and micro LC-MS/MS analysis were carried out as described in the previous study (Youn et al., 2010).

Data analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Comparisons of data between groups were performed by one-way ANOVA and Duncan's multiple range test. Values of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

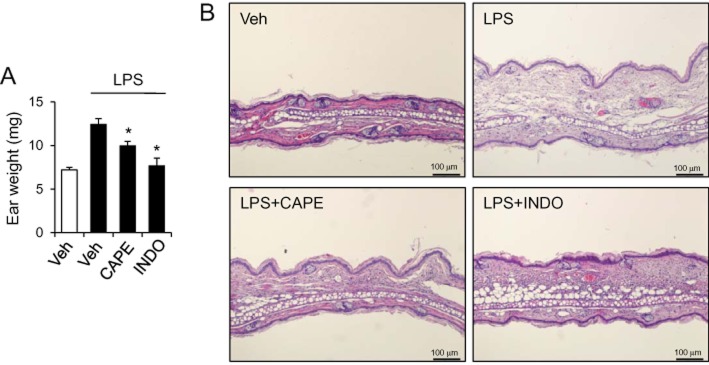

CAPE reduces inflammatory symptoms and production of pro-inflammatory mediators

CAPE has been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties (Michaluart et al., 1999). We tested whether CAPE had beneficial effect on the inflammatory symptoms in vivo using a LPS-induced skin inflammation animal model. Intradermal injection of LPS on mouse ear induced ear swelling as shown by increased ear weight (Figure 1A). Dermal application of CAPE prevented LPS-induced swelling and inflammatory responses as ear weight was decreased (Figure 1A). Its protective effect was compatible with that of indomethacin, a well-known non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, which was used as a positive control. Histological examination also showed an attenuation of dermal inflammation and oedema when the mice were treated with CAPE (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Topical application of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) reduces skin inflammation induced by intradermal injection of LPS in mice. CAPE (1%) or indomethacin (INDO; 0.5%) was applied to the centre of ear in mice and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (50 μg/25 μL) was intradermally injected on the ear. (A) Twenty-four hours after LPS injection, the weight of 6 mm biopsy of ears was measured. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 8–18). *Significantly different from LPS + vehicle, P < 0.05. (B) After weighing, biopsy tissues were processed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological examination. Representative pictures are presented. Veh is vehicle.

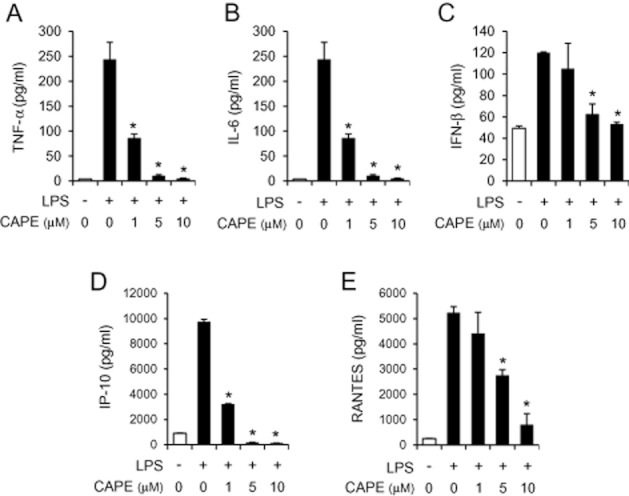

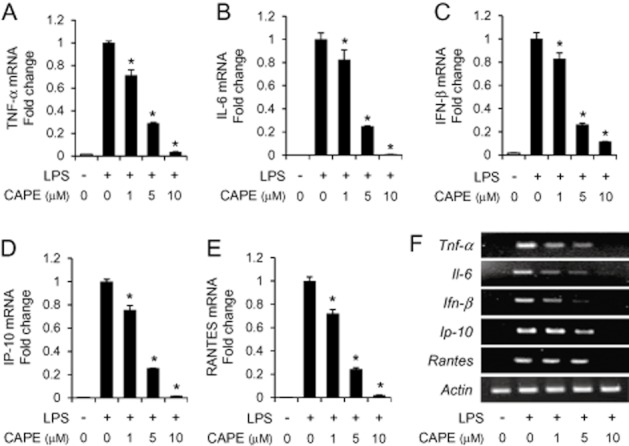

Pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines contribute to inflammatory responses by increasing vascular permeability, and stimulating the expression of adhesion molecules on vascular endothelium, the infiltration of leukocytes, and the activation of immune cells. Therefore, we examined whether CAPE decreased the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. When murine macrophages (RAW264.7) were stimulated with LPS in the presence or absence of CAPE, CAPE reduced the protein levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-6), IFN-β and IFN-inducible genes (IP-10 and RANTES) that increased in response to LPS (Figure 2A–E). The inhibition was achieved at the transcriptional level since the mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-β, IP-10 and RANTES increased by LPS treatment were down-regulated by CAPE in both RAW264.7 cells and bone marrow-derived primary macrophages (Figure 3A–F).

Figure 2.

Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) suppresses the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in macrophages. RAW264.7 cells were pre-treated with CAPE (1, 5 and 10 μM) for 1 h, and then stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 ng mL−1) for an additional (A, C) 8 h or (B, D, E) 24 h. Culture media were collected and analysed for TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-β, IP-10 and RANTES by ELISA. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). *Significantly different from LPS alone, P < 0.05.

Figure 3.

The mRNA levels of cytokines and chemokines are decreased by caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE). (A–E) RAW264.7 cells were pre-treated with CAPE (1, 5 and 10 μM) for 1 h, and further stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (10 ng mL−1) for an additional 4 h. The mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-β, IP-10, RANTES and β-actin were determined by quantitative real-time PCR analysis and normalized with β-actin. The mRNA level of each cytokine was expressed after normalization with LPS alone. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). *Significantly different from LPS alone, P < 0.05. (F) Bone marrow-derived primary macrophages were pre-treated with CAPE (1, 5 and 10 μM) for 1 h, and further stimulated with LPS (100 ng mL−1) for additional 4 h. The mRNA levels of TNF-α, IL-6, IFN-β, IP-10, RANTES and β-actin were determined by reverse transcription-PCR analysis.

CAPE suppresses ligand-induced, but not ligand-independent, activation of IRF3

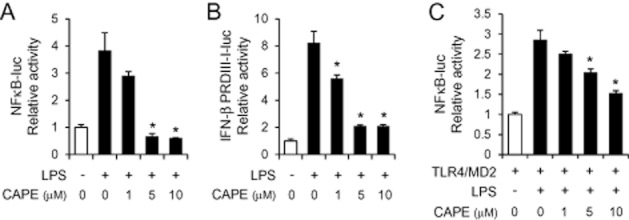

Since the expression of cytokines and chemokines was attenuated at the transcriptional level, we investigated whether CAPE affected activation of transcription factors such as NFκB and IRF3, which are two major transcription factors in TLR4 signalling. Activation of NFκB and IRF3 was determined by luciferase reporter gene assays using NFκB-luc to assess NFκB activation and IFN-β PRDIII-I-luc to measure IRF3 activation. CAPE significantly suppressed LPS-induced activation of NFκB and IRF3 in macrophages (RAW264.7) (Figure 4A and B) showing that CAPE inhibited the activation of endogenous TLR4 induced by a ligand, LPS. In addition, CAPE was able to block LPS-induced NFκB activation in 293T cells expressing exogenous TLR4/MD2 (Figure 4C). These demonstrate that CAPE inhibits ligand-dependent activation of TLR4 signalling.

Figure 4.

Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) prevents TLR4 ligand lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced activation of NFκB and IRF3. (A, B) RAW264.7 cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter plasmid containing NFκB binding sites (NFκB-luc) or IRF3 binding domain derived from the IFN-β promoter (IFN-β PRDIII-I-luc). (C) 293T cells were transfected with the expression plasmids for TLR4 and MD2 along with NFκB-luc. Cells were pre-treated with CAPE (1, 5 and 10 μM) for 1 h, and then stimulated with LPS (10 ng mL−1) for an additional 8 h. Cell lysates were analysed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities. Relative luciferase activity was calculated after normalization with β-galactosidase activity. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). *Significantly different from LPS alone, P < 0.05.

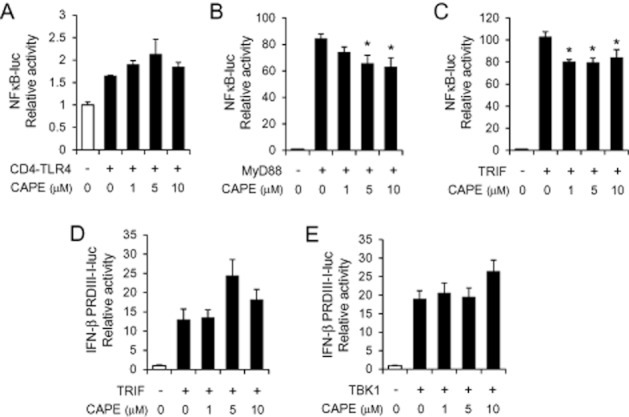

To narrow down the signalling step regulated by CAPE in TLR4 signalling pathways, we investigated whether downstream signalling molecules were inhibited by CAPE. NFκB and IRF3 were activated by overexpression of TLR4 signalling components in 293T cells in the presence and absence of CAPE. CAPE did not suppress NFκB activation induced by a constitutively active chimeric TLR4 (CD4-TLR4) (Figure 5A). Similarly, NFκB activation induced by overexpression of MyD88 or TRIF, which are immediate adaptor molecules of TLR4, was only marginally suppressed by CAPE (Figure 5B and C). Furthermore, it failed to inhibit activation of IRF3 induced by TRIF or TBK1 (Figure 5D and E).

Figure 5.

Ligand-independent activation of NFκB or IRF3 was marginally or not attenuated by caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE). 293T cells were transfected with the expression plasmid for CD4-TLR4, MyD88, TRIF or TBK1, and the luciferase reporter plasmid of NFκB-luc or IFN-β PRDIII-I-luc as indicated. Cells were further treated with CAPE (1, 5 and 10 μM) for 8 h. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). *Significantly different from (B) MyD88 alone or (C) TRIF alone, P < 0.05.

These results show that ligand (LPS)-induced activation of NFκB and IRF3 was significantly attenuated by CAPE whereas such inhibitory effect was not observed in ligand-independent activation of TLR4 signalling. Therefore, the results suggest that CAPE may target the interaction between ligand and the receptor complex resulting in attenuation of transcription factor activation and cytokine expression.

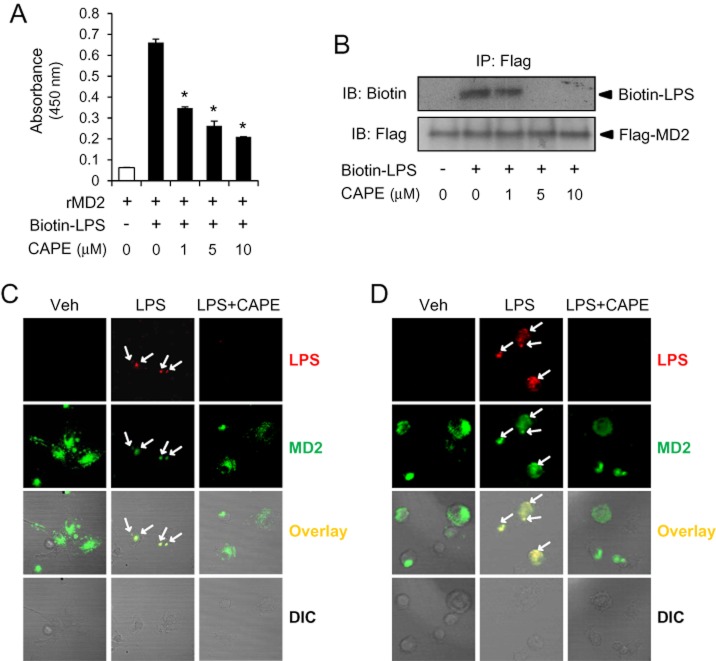

CAPE inhibits LPS binding to MD2

To identify anti-inflammatory target of CAPE in TLR4 signalling, we investigated whether it interfered with the interaction between LPS and TLR4 receptor complex. TLR4 exists as a complex with MD2 when it is expressed on cell surface. LPS binds to the hydrophobic pocket of MD2 triggering the dimerization of TLR4/MD2 complex and the activation of intracellular signals (Park et al., 2009). To examine whether CAPE prevented LPS binding to MD2, we performed in vitro binding assay to determine the level of LPS bound to recombinant MD2. Incubation of MD2 with biotinylated LPS resulted in the association of LPS with MD2 and the addition of CAPE reduced the amount of LPS bound to MD2 (Figure 6A). To confirm whether this inhibition was observed in cellular system, biotinylated LPS was added to Ba/F3 cells expressing flag-tagged MD2 and the amount of co-immunoprecipitated LPS and MD2 was determined by immunoblot analysis. Treatment with CAPE to the cells diminished the association of biotinylated LPS with MD2 (Figure 6B). Consistently, confocal microscopy analysis showed that co-localization of LPS with MD2 was observed at 15 and 30 min after LPS treatment in bone marrow-derived macrophages and that CAPE reduced the amount of co-localization of LPS and MD2 (Figure 6C and 6D). These results demonstrate that CAPE interferes with interaction of LPS with MD2.

Figure 6.

Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) inhibits lipopolysaccharide (LPS) binding to TLR4/MD2. (A) In vitro binding assay using recombinant MD2 (rMD2) and biotinylated LPS was performed to analyse LPS binding to MD2 as described in Methods. After CAPE was incubated with rMD2 for 1 h at 37°C, biotin-LPS (50 ng mL−1) was added to wells containing rMD2. (B) Ba/F3 cells expressing TLR4 and Flag-MD2 were pre-treated with CAPE for 1 h and then stimulated with biotin-labelled LPS (1 μg/group) for 20 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag antibody and immunoblotted to detect biotin-LPS and Flag-MD2. (C, D) Bone marrow-derived primary macrophages were pre-treated with CAPE (10 μM) for 1 h and then treated with Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated with LPS (1.5 μg/group) for 15 min (C) or 30 min (D). Cells were stained with anti-MD2 antibody together with FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. IP, immunoprecipitation; IB, immunoblot; DIC, differential interference contrast.

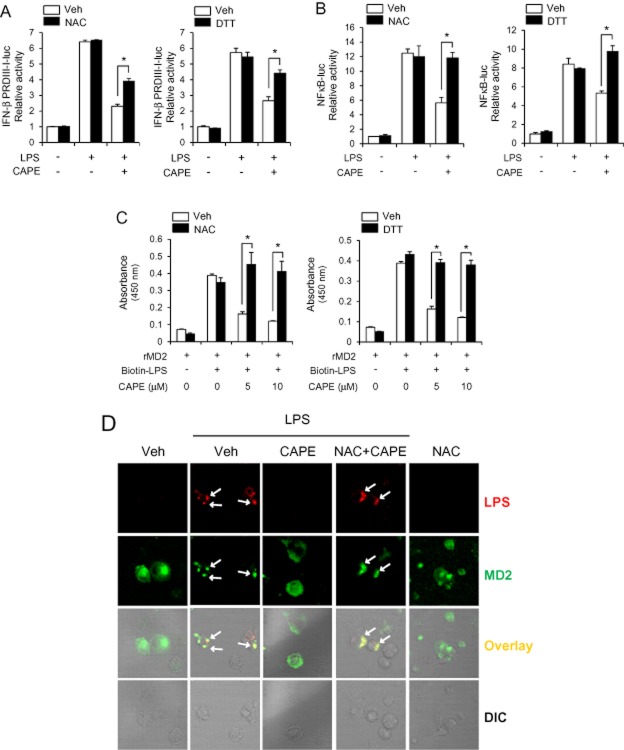

CAPE forms an adduct with Cys133 in MD2

Since CAPE has sulfhydryl modifying activity (Natarajan et al., 1996), we investigated whether the inhibitory effects of CAPE were dependent on its reactivity to sulfhydryl group. Supplementation of thiol donors, NAC and DTT, at concentrations used partially reversed the inhibitory effect of CAPE on LPS-induced IRF3 activation (Figure 7A). The inhibitory effect of CAPE on LPS-induced NFκB activation was also reversed by NAC and DTT treatment (Figure 7B). To confirm the reversal effect of thiol donor, we tested this in a different cell system using 293T cells where TLR4 and MD2 were expressed exogenously. In 293T cells expressing TLR4 and MD2, NAC almost fully reversed the inhibitory effects of CAPE on LPS-induced IRF3 activation as well as NFκB activation (Supporting Information Fig. S1). These show that thiol supplementation can block the inhibitory effect of CAPE on TLR4 activation.

Figure 7.

The inhibitory effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) on IRF3 activation and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-MD2 association are reversed by thiol-donors. (A) RAW264.7 cells were transfected with IFN-β PRDIII-I-luc. Cells were further pre-treated with CAPE (10 μM) in the absence or presence of N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC, 2 mM) or dithiothreitol (DTT, 300 μM) for 1 h and stimulated with LPS (10 ng mL−1) for 8 h. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05. (B) Ba/F3 cells expressing TLR4, MD2 and NFκB-luc were pre-treated with CAPE (10 μM) in the absence or presence of NAC (1 mM) or DTT (200 μM) for 1 h and stimulated with LPS (1 ng mL−1) for 8 h. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05. (C) In vitro assay for LPS binding to MD2 was performed. CAPE was pre-incubated with NAC (50 μM) or DTT (50 μM) for 30 min at 37°C and then further incubated with rMD2 for 30 min at 37°C. Biotin-LPS was added to wells containing rMD2. Values are means ± SEM (n = 3). *P < 0.05. (D) Bone marrow-derived primary macrophages were pre-treated with CAPE (10 μM) in the absence or presence of NAC (2 mM) for 1 h and then treated with Alexa Fluor 594 conjugated with LPS (1.5 μg/group) for 30 min. Cells were stained with anti-MD2 antibody together with FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody. DIC, differential interference contrast.

In addition, NAC and DTT reversed the inhibitory effect of CAPE on LPS binding to MD2 as assessed by in vitro binding assay (Figure 7C). Furthermore, NAC treatment reversed the blockade of LPS-MD2 co-localization by CAPE in bone marrow-derived macrophages (Figure 7D). These results suggest that the inhibitory effect of CAPE on TLR4 activation is due to its sulfhydryl modifying activity.

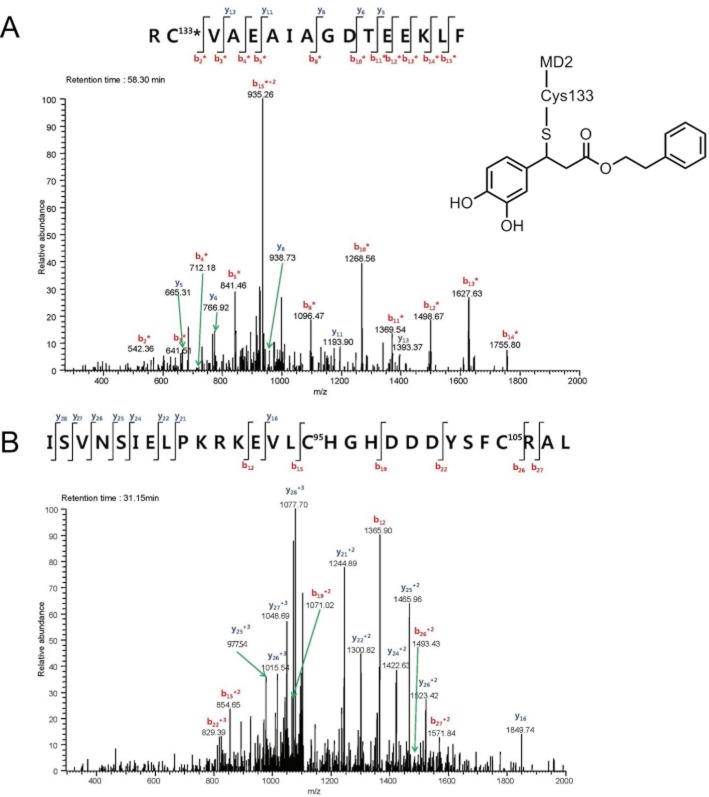

To further define whether CAPE directly binds to cysteine residue in MD2, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis was performed after incubation of recombinant MD2 with CAPE. The results showed that CAPE formed an adduct with Cys133 in the hydrophobic pocket of MD2 (Figure 8A). Modification of Cys133 in MD2 has been suggested as an inhibitory target for LPS-induced cell activation (Mancek-Keber et al., 2009). Cys133 is a free cysteine residue whereas Cys95 and Cys105 participate in the formation of intramolecular disulfide bond. CAPE did not bind to Cys95 and Cys105 at the current experimental condition in this study (Figure 8B) showing that the binding of CAPE is rather preferential for a free cysteine residue. These results indicate that CAPE directly binds to MD2, thereby blocking the interaction of LPS to MD2.

Figure 8.

Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) forms an adduct with Cys133 in MD2. Recombinant mouse MD2 (1 μg) was incubated with CAPE (20 μM) for 1 h at 37°C prior to in-solution digestion and micro liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis. MS/MS spectrum of the CAPE-Cys133 adduct was acquired using a LTQ linear ion trap mass spectrometer. MS/MS spectra of mouse MD2 sequences (A, Arg132-Phe147, RC133VAEAIAGDTEEKLF; B, Ile80-Leu108, SVNSIELPKRKEVLC95HGHDDDYSFC105RAL) were selected and the fragment ions were assigned as b (red colour) or y (blue colour) series ions. Mass accuracy of ±0.5 Da was used in the assignments. * denotes fragment ions with one CAPE. The proposed structure of CAPE-Cys133 MD2 adduct is presented in (A).

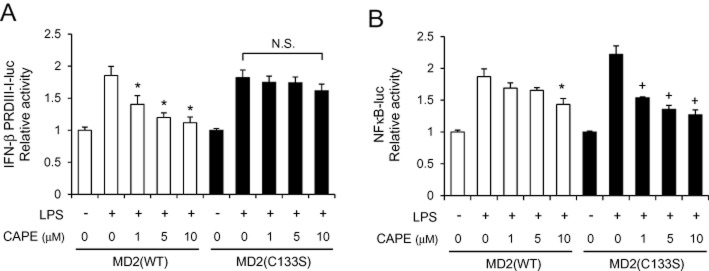

To confirm that the inhibitory effect of CAPE on TLR4 signalling is dependent on Cys133 in MD2, we performed the reconstitution studies using WT MD2 and C133S mutant MD2 (Figure 9). The 293T cells were transfected with the expression plasmids of TLR4 and MD2(WT) or MD2(C133S). IFN-β PRDIII-I-luc and NFκB-luc were used to determine IRF3 activation and NFκB activation respectively. MD2(C133S) conferred the responsiveness to LPS to activate IRF3 as well as NFκB (Figure 9A and B). CAPE suppressed IRF3 activation induced by LPS in 293T cells reconstituted with TLR4 and MD2(WT). However, the inhibitory effect on IRF3 activation was not observed when cells were reconstituted with MD2(C133S) mutant (Figure 9A). Statistical analysis has shown that there was no significant difference between LPS alone and LPS + CAPE at 1, 5 and 10 μM in 293T cells with MD2(C133S) (Figure 9A). These show that the inhibitory effect of CAPE on LPS-induced IRF3 activation is dependent on the modification of Cys133 residue in MD2 resulting in the blockade of ligand-receptor association. In contrast, the suppression of NFκB activation by CAPE was observed in MD2(C133S)-reconstituted cells as well as MD2(WT)-reconstituted cells (Figure 9B). This may be due to the direct modulation of NFκB pathway by CAPE at downstream of receptor signalling.

Figure 9.

Inhibition of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced IRF3 activation by caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) is dependent on Cys133 in MD2. (A) 293T cells were transfected with the expression plasmids of TLR4, TRIF and IFN-β PRDIII-I-luc with MD2 wild-type (WT) or MD2 (C133S). (B) 293T cells were transfected with the expression plasmids for TLR4 and NFκB-luc with MD2 (WT) or MD2 (C133S). (A, B) Cells were pre-treated with CAPE for 1 h and then stimulated with LPS (10 ng mL−1) for an additional 8 h. Cell lysates were analysed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities to determine relative luciferase activity. *Significantly different from LPS alone with MD2 (WT). +, significantly different from LPS alone with MD2 (C133S), P < 0.05. N.S., not significant.

Collectively, our results demonstrate that the anti-inflammatory activity of CAPE is mediated at least partly through blockade of LPS binding to the TLR4/MD2 complex resulting in down-regulation of the activation of TLR4-downstream signalling pathways and inflammatory gene expression.

Discussion

Our results demonstrate that MD2 is a novel anti-inflammatory target of CAPE and that CAPE interrupts the association of LPS with MD2 resulting in down-regulation of TLR4 activation and inflammatory gene expression. LPS derived from bacteria binds to LPS binding protein and CD14 and then is presented to TLR4/MD2 complex (Miyake, 2006). MD2, which lacks transmembrane and intracellular domains, is associated with the extracellular domain of TLR4 and interacts with LPS (Park et al., 2009). Binding of LPS to a hydrophobic pocket in MD2 results in the formation of receptor multimer composed of two sets of TLR4/MD2/LPS complex, and leads to the recruitment of adaptor proteins and the activation of intracellular signalling pathways (Park et al., 2009). Since LPS antagonists, lipid IVa and eritoran, also bind to MD2 and block TLR4 activation (Kim et al., 2007; Park et al., 2009), the interaction between LPS and MD2 could be a useful target for anti-inflammatory agents designed to prevent LPS-mediated TLR4 activation. Our results from in vitro binding assay using biotinylated LPS and recombinant MD2 as well as cell-based co-immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis with biotinylated LPS and Flag-MD2 demonstrated that CAPE prevented binding of LPS to MD2. Confocal microscopic analysis further confirmed that CAPE blocked LPS binding to macrophages and co-localization of LPS and TLR4/MD2. These suggest that CAPE may interact with LPS or MD2 to prevent LPS binding to MD2. Since it has been reported that certain cysteines in MD2 play an essential role to confer LPS responsiveness, we attempted to investigate whether CAPE can modify cysteine in MD2. Cys133 has been proposed to be a target amino acid for certain thiol-reactive compounds such as 2-[4′-(iodoacetamido)aniline]naphthalene-6-sulfonic acid and N-pyrene maleimide to block LPS responsiveness (Mancek-Keber et al., 2009). However, not all thiol-reactive compounds target Cys133, since curcumin which has α,β-unsaturated aldehyde moiety highly reactive to thiol groups through Michael addition, did not seem to covalently bind to Cys133 (Gradisar et al., 2007). With liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis, we were able to identify Cys133 in MD2 as the direct binding site for CAPE. To our knowledge, this is the first report showing the direct binding of Cys133 by anti-inflammatory phytochemical using proteomic approach. In addition to Cys133, Cys95 and Cys105 in MD2 were also suggested to play an important role in interaction of TLR4 with MD2 and responsiveness to LPS as demonstrated by studies using MD2 mutants at Cys95 and Cys105 (Schromm et al., 2001; Mullen et al., 2003; Re and Strominger, 2003). CAPE did not bind to Cys95 and Cys105 according to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis, possibly because Cys95 and Cys105 form disulfide bond and are less accessible as compared with free cysteine, Cys133. It is also possible that CAPE at high concentration may interact with LPS to prevent LPS binding to MD2. However, for in vitro binding assay, after MD2 was incubated with CAPE, the wells were washed out with PBS and then biotinylated LPS was added to wells containing MD2 in the absence of CAPE. Therefore, these suggest that blockade of LPS binding to MD2 is primarily mediated through interaction of CAPE with MD2.

CAPE is known to have multiple targets for its anti-inflammatory activity. Inhibitory effect of CAPE on NFκB activation has been observed with many inflammatory agents, both receptor-mediated stimuli such as TNF-α and non-receptor-mediated activators such as phorbol ester, ceramide and hydrogen peroxide (Natarajan et al., 1996). Inhibition of LPS-induced NFκB activation was also shown as CAPE reduced NFκB DNA binding activity, nuclear translocation of p65, and degradation of IκB in macrophages (RAW264.7) and monocyte-derived dendritic cells stimulated with LPS (Jung et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2009). The inhibitory mechanism as to how CAPE inhibits NFκB was suggested to be partly the inhibition of IKKα/β activity as shown by in vitro immunocomplex kinase assay with colon tumour cells (HCT116) stimulated with TNF-α (Lee et al., 2010). The activation of Nrf2 was also suggested to play a role in inhibitory effect of CAPE on TNF-α-induced NFκB activation at relatively higher concentrations than those used in our study (Lee et al., 2010). In this study, we attempted to find a novel target in TLR4 signalling pathway. In contrast to other studies showing the direct inhibition of NFκB at downstream step, our results showed that constitutive TLR4-induced NFκB activation was not inhibited by CAPE in 293T cells and that MyD88- and TRIF-induced NFκB activation was only marginally reduced by CAPE in 293T cells. However, CAPE more dramatically suppressed NFκB activation induced by LPS in 293T cells reconstituted with TLR4 and MD2. These results prompted us to investigate whether CAPE has the upstream target around ligand-receptor complex. The discrepancy could be derived from different experimental context of cell type and stimuli. The results from in vitro binding assay, LC-MS/MS analysis and the reconstitution experiment using MD2(C133S) mutant showed that the interaction of CAPE with Cys133 in MD2 is a novel mechanism for the inhibitory effect of CAPE on TLR4 activation. When chemicals are treated to cells, the extracellular part of cells would be firstly exposed to chemicals prior to the exposure of cytosolic part. This suggests that MD2 expressed on cellular membrane may be one of the first targets to encounter with chemicals and to be affected by them. The reconstitution experiment using MD2(C133S) mutant showed different results for inhibitory effects of CAPE on NFκB activation and IRF3 activation. Inhibitory effect of CAPE on IRF3 activation was not observed when 293T cells were reconstituted with MD2(C133S) mutant showing that inhibition of LPS-induced IRF3 activation by CAPE is mediated through the modification of MD2. In contrast, inhibitory activity of CAPE for LPS-induced NFκB activation was still observed in 293T cells reconstituted with MD2(C133S) mutant. These suggest that the suppressive effect of CAPE on LPS-induced NFκB activation may be dependent on the direct effect of CAPE on NFκB pathway. Nevertheless, it is possible that inhibition of LPS binding to MD2 by CAPE at least partly contributes to the reduction of NFκB activation.

Topical application of CAPE attenuated local inflammatory symptoms induced by intradermal injection of LPS to mouse ear. These suggest that CAPE can be used as a beneficial agent to prevent inflammatory diseases associated with TLR4 activation. In fact, CAPE showed the preventive effect on gastritis in Mongolian gerbils infected with Helicobacter pylori (Toyoda et al., 2009), which is known to activate TLR4 (Gobert et al., 2004). MD2 is suggested as an essential component for H. pylori-mediated gastritis since transcripts of TLR4 and MD2 were up-regulated in gastric tissue of patients with H. pylori-positive chronic gastritis and up-regulated MD2 expression accelerated H. pylori LPS-mediated NFκB activation in gastric adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line (Ishihara et al., 2004). These suggest that the blockade of ligand-TLR4/MD2 interaction may contribute to the prevention of H. pylori-induced inflammatory symptoms by CAPE.

Collectively, our results reveal that LPS binding to TLR4/MD2 complex is a novel anti-inflammatory target of CAPE, leading to the decrease of downstream signal activation and inflammatory mediator expression. Our findings may provide beneficial information for the development of therapeutic strategies to prevent chronic inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hyo Jung Lee and Sun Myung Joung for their technical assistance. This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (No. 1120120), a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MEST) (No. 2012R1A1A3004541), and the Research Fund, 2012 of the Catholic University of Korea.

Glossary

- CAPE

caffeic acid phenethyl ester

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- IFN

interferon

- IKK

inhibitor of kappaB kinase

- IL-12

Interleukin 12

- IRF3

interferon-regulatory factor 3

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MyD88

myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88

- NAC

N-acetyl-L-cysteine

- RIP1

receptor-interacting protein 1

- TBK1

TANK-binding kinase 1

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- TNF

tumour necrosis factor

- TRIF

TIR-domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon-beta

Conflict of interest

All of the authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Figure S1 The inhibitory effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) on LPS-induced activation of IRF3 and NFκB are reversed by thiol-donor in 293T cells reconstituted with TLR4 and MD2. (A) 293T cells were transfected with the expression plasmids for TLR4, TRIF and MD2 along with IFN-β PRDIII-I-luc. (B) 293T cells were transfected with the expression plasmids for TLR4 and MD2 along with NFκB-luc. (A, B) Cells were pre-treated with CAPE in the absence or presence of NAC (2 mM) for 1 h, and then stimulated with LPS (10 ng mL−1) for an additional 8 h. Cell lysates were analysed for luciferase and β-galactosidase activities. Relative luciferase activity was calculated after normalization with β-galactosidase activity. *P < 0.05.

References

- Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald KA, McWhirter SM, Faia KL, Rowe DC, Latz E, Golenbock DT, et al. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:491–496. doi: 10.1038/ni921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel K, Wei H, Bhimani R, Ye J, Zadunaisky JA, Huang MT, et al. Inhibition of tumor promoter-mediated processes in mouse skin and bovine lens by caffeic acid phenethyl ester. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1255–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobert AP, Bambou JC, Werts C, Balloy V, Chignard M, Moran AP, et al. Helicobacter pylori heat shock protein 60 mediates interleukin-6 production by macrophages via a toll-like receptor (TLR)-2-, TLR-4-, and myeloid differentiation factor 88-independent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:245–250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307858200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradisar H, Keber MM, Pristovsek P, Jerala R. MD-2 as the target of curcumin in the inhibition of response to LPS. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:968–974. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1206727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara S, Rumi MA, Kadowaki Y, Ortega-Cava CF, Yuki T, Yoshino N, et al. Essential role of MD-2 in TLR4-dependent signaling during Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis. J Immunol. 2004;173:1406–1416. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.2.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joung SM, Park ZY, Rani S, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Lee JY. Akt contributes to activation of the TRIF-dependent signaling pathways of TLRs by interacting with TANK-binding kinase 1. J Immunol. 2011;186:499–507. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung WK, Choi I, Lee DY, Yea SS, Choi YH, Kim MM, et al. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester protects mice from lethal endotoxin shock and inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages via the p38/ERK and NF-kappaB pathways. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2572–2582. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzler H, Barrat FJ, Hessel EM, Coffman RL. Therapeutic targeting of innate immunity with Toll-like receptor agonists and antagonists. Nat Med. 2007;13:552–559. doi: 10.1038/nm1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai T, Adachi O, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Unresponsiveness of MyD88-deficient mice to endotoxin. Immunity. 1999;11:115–122. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keogh B, Parker AE. Toll-like receptors as targets for immune disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HM, Park BS, Kim JI, Kim SE, Lee J, Oh SC, et al. Crystal structure of the TLR4-MD-2 complex with bound endotoxin antagonist Eritoran. Cell. 2007;130:906–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koksel O, Ozdulger A, Tamer L, Cinel L, Ercil M, Degirmenci U, et al. Effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester on lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury in rats. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2006;19:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JK, Kim SY, Kim YS, Lee WH, Hwang DH, Lee JY. Suppression of the TRIF-dependent signaling pathway of Toll-like receptors by luteolin. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:1391–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Hwang DH. The modulation of inflammatory gene expression by lipids: mediation through Toll-like receptors. Mol Cells. 2006;21:174–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Shin DH, Kim JH, Hong S, Choi D, Kim YJ, et al. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester-mediated Nrf2 activation and IkappaB kinase inhibition are involved in NFkappaB inhibitory effect: structural analysis for NFkappaB inhibition. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;643:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancek-Keber M, Gradisar H, Inigo Pestana M, Martinez De Tejada G, Jerala R. Free thiol group of MD-2 as the target for inhibition of the lipopolysaccharide-induced cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19493–19500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meylan E, Burns K, Hofmann K, Blancheteau V, Martinon F, Kelliher M, et al. RIP1 is an essential mediator of Toll-like receptor 3-induced NF-kappa B activation. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:503–507. doi: 10.1038/ni1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaluart P, Masferrer JL, Carothers AM, Subbaramaiah K, Zweifel BS, Koboldt C, et al. Inhibitory effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester on the activity and expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in human oral epithelial cells and in a rat model of inflammation. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2347–2352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake K. Roles for accessory molecules in microbial recognition by Toll-like receptors. J Endotoxin Res. 2006;12:195–204. doi: 10.1179/096805106X118807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen GE, Kennedy MN, Visintin A, Mazzoni A, Leifer CA, Davies DR, et al. The role of disulfide bonds in the assembly and function of MD-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3919–3924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630495100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan K, Singh S, Burke TR, JR, Grunberger D, Aggarwal BB. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester is a potent and specific inhibitor of activation of nuclear transcription factor NF-kappa B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9090–9095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshiumi H, Matsumoto M, Funami K, Akazawa T, Seya T. TICAM-1, an adaptor molecule that participates in Toll-like receptor 3-mediated interferon-beta induction. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:161–167. doi: 10.1038/ni886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park BS, Song DH, Kim HM, Choi BS, Lee H, Lee JO. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4-MD-2 complex. Nature. 2009;458:1191–1195. doi: 10.1038/nature07830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, et al. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Re F, Strominger JL. Separate functional domains of human MD-2 mediate Toll-like receptor 4-binding and lipopolysaccharide responsiveness. J Immunol. 2003;171:5272–5276. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh S, Akashi S, Yamada T, Tanimura N, Kobayashi M, Konno K, et al. Lipid A antagonist, lipid IVa, is distinct from lipid A in interaction with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-MD-2 and ligand-induced TLR4 oligomerization. Int Immunol. 2004;16:961–969. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schromm AB, Lien E, Henneke P, Chow JC, Yoshimura A, Heine H, et al. Molecular genetic analysis of an endotoxin nonresponder mutant cell line: a point mutation in a conserved region of MD-2 abolishes endotoxin-induced signaling. J Exp Med. 2001;194:79–88. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda T, Tsukamoto T, Takasu S, Shi L, Hirano N, Ban H, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE), a nuclear factor-kappaB inhibitor, on Helicobacter pylori-induced gastritis in Mongolian gerbils. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:1786–1795. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang LC, Lin YL, Liang YC, Yang YH, Lee JH, Yu HH, et al. The effect of caffeic acid phenethyl ester on the functions of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. BMC Immunol. 2009;10:39. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-10-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn HS, Kim YS, Park ZY, Kim SY, Choi NY, Joung SM, et al. Sulforaphane suppresses oligomerization of TLR4 in a thiol-dependent manner. J Immunol. 2010;184:411–419. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.