Abstract

Extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli strains are believed to be widely distributed among humans and animals; however, to date, there are only few studies that support this assumption on a regional or countrywide scale. Therefore, a study was designed to assess the prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli in dairy cows and beef cattle in the southern part of Bavaria, Germany. The study population included 30 mixed dairy and beef cattle farms and 15 beef cattle farms. Fecal samples, boot swabs, and dust samples were analyzed for ESBL-producing E. coli using selective media. PCR was performed to screen for CTX-M and ampC resistance genes. A total of 598 samples yielded 196 (32.8%) that contained ESBL-producing E. coli, originating from 39 (86.7%) of 45 farms. Samples obtained from mixed farms were significantly more likely to be ESBL-producing E. coli positive than samples from beef cattle farms (fecal samples, P < 0.001; boot swabs, P = 0.014; and dust samples, P = 0.041). A total of 183 isolates (93.4%) of 196 ESBL-producing E. coli-positive strains harbored CTX-M genes, CTX-M group 1 being the most frequently found group. Forty-six additional isolates contained ampC genes, and 5 of the 46 isolates expressed a blaCMY-2 gene. The study shows that ESBL-producing E. coli strains are commonly found on Bavarian dairy and beef cattle farms. Moreover, to our knowledge, this is the first report of the occurrence of blaCMY-2 in cattle in Germany.

INTRODUCTION

An increasing number of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) have been identified in Enterobacteriaceae during the last few years. They were not only detected in humans (1, 2), but also in a broad range of animal species ranging from companion animals (3–5) to food animals (6–10), and they could also be found in food (11, 12). Extended-spectrum β-lactamases are plasmid-encoded enzymes that inactivate a large number of β-lactam antibiotics, including extended-spectrum and very-broad-spectrum cephalosporins and monobactams. They are also commonly inhibited by β-lactamase inhibitors, such as clavulanic acid, sulbactam, and tazobactam. Furthermore, resistance to broad-spectrum cephalosporins can be due to overexpression of chromosomal or plasmid-mediated AmpC enzymes, encoded by genes such as blaCMY-2. These enzymes also confer resistance to cephamycins and cannot be inhibited by β-lactamase inhibitors. Since first emerging in the late 1980s, blaCTX-M genes have become the most common genes encoding ESBL in many countries. They have been reported to be isolated from different food-producing animals that were recognized as reservoirs for ESBL-producing E. coli (13). Several studies indicate that these resistance genes are disseminated through the food chain or via direct contact with humans and animals (14, 15). The data about ESBL-producing bacteria in food animals in Germany are very limited. To date, only one publication on the detection of ESBL-producing E. coli in food animals in Germany has been available (16). Therefore, this study was conducted to estimate the prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli in healthy cattle, evaluating different ages and farm types.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and sampling.

In this study, 45 randomly selected farms were enrolled in the southern part of Bavaria, Germany, from summer 2011 until summer 2012. Thirty farms were mixed dairy and beef cattle farms where three groups (calves, lactating dairy cows, and beef cattle) were sampled and tested. The mean herd sizes were 57 ± 37.1 cows, 24 ± 16.2 calves, and 44 ± 35.5 beef cattle. The cows enrolled in this study were between 2 and 15 years old, and the calves were at least 2 days old, with the oldest being 6 months of age. Half of the farms housed dairy cows in free-stall barns and half of them in tie-stall barns. Most farms used hutches and individual pens for their calves. All beef cattle were housed in pens with six to eight animals each. The mean ages at slaughter were 4 ± 0 months for veal calves and 20 ± 2.2 months for beef cattle. Fifteen farms were exclusively beef cattle farms, where the youngest and the oldest groups were tested. On most farms, beef cattle were housed in pens with six to eight animals each. The mean size of herds was 130 ± 108.5, and the mean age of bulls at slaughter was 20 ± 2.3 months. In addition to the 45 survey farms, 9 combined cow and calf herds (the “cow-calf” group) and one beef cattle farm were enrolled as a control group not having used antimicrobials for at least half a year.

From every group on each farm, three pooled fecal samples, one dust sample, and a pair of boot swabs from the feed alley were collected (Table 1). On mixed farms, 10 fecal samples from cows were collected for one pooled fecal sample and six fecal samples from calves and six fecal samples from bulls were included into one pooled fecal sample from each group. On beef cattle farms, one pooled fecal sample represented six to eight bulls from one pen. On one farm, only two pooled fecal samples could be collected from calves and beef cattle as there were only two calves in each group. If dust could not be collected, it was replaced by another pair of boot swab samples.

Table 1.

Numbers and distributions of samples collected from farms

| Sample source (n) | No. of samples |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal (3/group) | Boot swabs (1 pair/group) | Dust (1/group) | |

| Mixed farms (30) | |||

| Cows | 90 | 31 | 29b |

| Calves | 89a | 30 | 30 |

| Beef cattle | 89a | 31 | 29b |

| Sum | 268 | 92 | 88 |

| Beef cattle farms (15) | |||

| Youngest group | 45 | 15 | 15 |

| Oldest group | 45 | 16 | 14b |

| Sum | 90 | 31 | 29 |

| Control group (10) | |||

| Cow-calf herds (9) | 27 | 9 | 3c |

| Beef cattle farms (1) | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| Sum | 33 | 11 | 5 |

There were not enough animals for a third fecal sample.

A dust sample was replaced with another pair of boot swabs.

If not on pasture, a dust sample was collected as well.

Cow and calf herds were tested as one cow-calf group. Mostly these animals were on pasture, so there was only the possibility of taking boot swabs. Where possible, a dust sample was taken also (Table 1).

Microbiological methods and susceptibility tests.

ESBL-producing E. coli strains were detected using an enrichment procedure: A 5-g aliquot of the fecal sample was placed in 45 ml Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), 1 ml of the dust suspension (0.1 g of the dust sample in 10 ml phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] [Merck, Germany] with 0.01% Tween20 [Merck, Germany]) in 9 ml of LB broth, and a pair of boot swabs in 225 ml of LB broth. The LB broth was incubated for 24 h under aerobic conditions at ±37°C, and 10 μl of each sample was streaked onto MacConkey agar (MCA) (Oxoid, United Kingdom) containing cefotaxime (1 μg/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), which was incubated for another 24 h under aerobic conditions at ±37°C.

Fecal samples and dust suspensions from 35 farms (21 mixed farms and 14 beef cattle farms) were additionally plated directly onto MCA with cefotaxime, omitting the enrichment step.

Coliform colonies growing on MCA with cefotaxime were subcultured on blood agar (Oxoid, United Kingdom), biochemically identified as E. coli, and phenotypically identified as ESBL or AmpC producers using the Phoenix system with panel NMIC/ID-76 (Becton, Dickinson, Germany). The breakpoints used were those defined by EUCAST for Enterobacteriaceae (http://www.eucast.org).

Molecular characterization.

Isolates that were phenotypically identified as ESBL producers were screened for the presence of blaCTX-M genes by real-time PCR using detection systems described by Birkett et al. (17). DNA was purified with the QIAamp DNA stool minikit (Qiagen, Germany). The presence of ampC β-lactamase genes was detected in phenotypic AmpC isolates by PCR too (18). Phenotypically ESBL-positive but genotypically negative CTX-M and AmpC isolates were also screened for blaTEM and blaSHV by real-time PCR (19), and DNA was sequenced afterwards.

Survey data.

On the day of the sample collection, the farmers answered a survey assessing basic herd information: e.g., demographic information, animal purchase, housing, performance, hygiene management, and use of antimicrobials. Information was collected for all animals of the tested groups and analyzed to assess possible risk factors for the spread of ESBL-producing E. coli.

Statistical analysis.

The data were entered into MS Excel (version 2010; Microsoft) and analyzed using Epi Info (StatCalc, version 6; CDC, Atlanta, GA) and SPSS (version 19; IBM, Germany). For categorical data, chi-square tests were performed. If the sample size was less than 30, a Yates' correction was applied. If any of the expected cell frequencies was less than 5, Fisher's exact test was used. Continuous data were examined visually for normal distribution (box plot) and analyzed for differences between groups using Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test. Differences with P ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Between July 2011 and June 2012, 45 farms were screened for ESBL-producing E. coli. In total, 598 samples were collected and in 196 (32.8%) samples, ESBL-producing E. coli strains were detected. At the farm level, at least one sample of 39 (86.7%) farms was found to be positive for ESBL-producing E. coli: i.e., 28 of 30 (93.3%) mixed farms and 11 of 15 (73.3%) beef cattle farms tested positive. The prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli on mixed farms was 38% for all samples, compared to 17.3% of all samples from beef cattle farms and 6.1% of samples from the control group. The highest rates of ESBL-producing E. coli on mixed farms could be detected in calves, with 56.2% of fecal samples harboring ESBL-producing E. coli, followed by cows (41.1% of fecal samples) and beef cattle (21.4% of fecal samples) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Percentages of ESBL-producing E. coli-positive samples and confidence intervals

| Sample source | No. of samples/total (%) [CI] |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal | Boot swabs | Dust | |

| Mixed farms | |||

| Cows | 37/90 (41.1) [31.5–51.4] | 14/31 (45.2) [29.2–62.2] | 5/29 (17.2) [7.6–34.6] |

| Calves | 50/89 (56.2) [45.8–66.0] | 21/30 (70) [52.1–83.3] | 12/30 (40) [24.6–57.7] |

| Beef cattle | 19/89 (21.4) [14.1–31.0] | 12/31 (38.7) [23.7–56.2] | 0/29 (0) [0.0–11.7] |

| Sum | 106/268 (39.6) [33.9–45.5] | 47/92 (51.1) [41.0–61.1] | 17/88 (19.3) [12.4–28.8] |

| Beef cattle farms | |||

| Youngest group | 12/45 (26.7) [16.0–41.0] | 3/15 (20) [7.1–45.2] | 1/15 (6.7) [1.2–29.8] |

| Oldest group | 5/45 (11.1) [4.8–23.5] | 5/16 (31.3) [14.2–55.6] | 0/14 (0) [0.0–21.5] |

| Sum | 17/90 (18.9) [12.1–28.2] | 8/31 (25.8) [13.7–43.3] | 1/29 (3.5) [0.6–17.2] |

| Total sum for mixed farms and beef cattle farms | 123/358 (34.4) [29.6–39.4] | 55/123 (44.7) [36.2–53.5] | 18/117 (15.4) [10.0–23.0] |

| Control group | 0/33 (0) [0.0–10.4] | 3/11 (27.3) [9.8–56.6] | 0/5 (0) [0.0–43.5] |

In the control group, 3 of 10 (30%) farms were positive for ESBL-producing E. coli, with one positive boot swab sample on each farm (Table 2). No ESBL-producing E. coli strains could be detected in fecal or dust samples from control farms.

An overall significant difference in prevalence was shown between mixed farms and beef cattle farms in comparison to the control group. Mixed and beef cattle farms were more likely to harbor samples containing ESBL-producing E. coli strains than the control group (P < 0.001, relative risk [RR] = 5.35; confidence interval [CI], 1.8 to 16.1).

Samples obtained from mixed farms were significantly more often positive for ESBL-producing E. coli than samples from beef cattle farms (fecal samples, P < 0.001, RR = 2.09, CI, 1.3 to 3.3; boot swabs, P = 0.014, RR = 1.98, CI, 1.1 to 3.7; and dust samples, P = 0.041, RR = 5.60; CI, 0.8 to 40.3). On mixed farms, the overall recovery of ESBL-producing E. coli was significantly more likely for calves (55.7%) than for cows (37.3%) (P = 0.002; RR, 1.49; CI, 1.2 to 1.9). Fecal samples and boot swabs from calves were significantly more often positive than those from dairy cows (fecal samples, P = 0.044, RR = 1.37, CI, 1.0 to 1.9; boot swabs, P = 0.049, RR = 1.55, CI, 1.0 to 2.4). On mixed farms, the prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli for all samples differed significantly between calves and beef cattle (fecal samples, P < 0.001, RR = 2.63, CI, 1.7 to 4.1; boot swabs, P = 0.014, RR = 1.81, CI, 1.1 to 3.0; dust samples, P < 0.001).

Farms of the control group showed no positive fecal samples (P < 0.001 compared to mixed farms, P = 0.006 compared to beef cattle farms).

Among all farms, 35 were screened for ESBL-producing E. coli with and without the enrichment step. In 41 of 273 (15%) fecal samples, ESBL-producing E. coli strains could be detected directly and with enrichment, compared to 79 (28.9%) of only enriched fecal samples. All 13 dust samples needed an enrichment step to detect ESBL-producing E. coli.

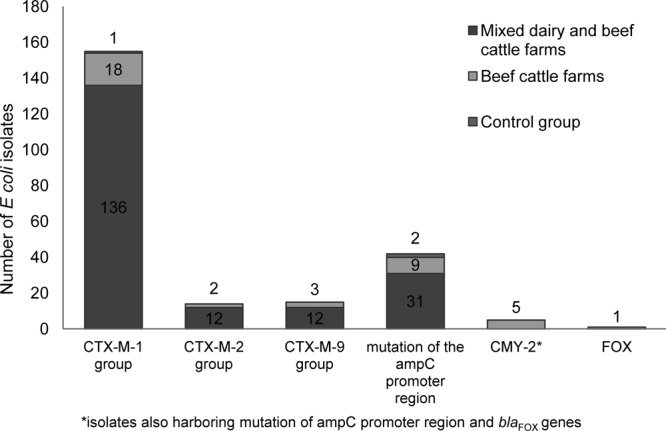

PCR was performed on all 196 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates to screen for CTX-M genes. A total of 183 isolates (93.4%) harbored CTX-M genes, CTX-M group 1 being the most frequently found group (Fig. 1). One isolate was identified as a TEM-52-harboring E. coli strain. Phenotypically ESBL-positive but genotypically negative CTX-M isolates were categorized as ESBL producers as the performed PCRs screened for the most common resistance genes but didn't include all existing resistance genes.

Fig 1.

Distribution of β-lactamase genes in 184 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates and 48 AmpC-producing E. coli isolates from mixed dairy and beef cattle farms and beef cattle farms.

In addition, 48 separate isolates that were phenotypically identified as AmpC producers using the Phoenix system (Becton Dickinson, Germany) were screened for genes encoding AmpC β-lactamases, which were found in 46 of the 48 isolates. Most isolates harbored mutations in the AmpC promoter region at base −42, a C→T transition, and at position −32, a T→A transversion. This mutation leads to overexpression of the chromosomal AmpC β-lactamase genes and overproduction of these enzymes (20). On mixed farms, AmpC production was only related to mutations in the AmpC promoter region, in contrast to beef cattle farms, where 6 isolates showed a plasmid-encoded AmpC production (Fig. 1). Twelve isolates harbored gene sequences for both CTX-M and AmpC. Phenotypically AmpC-positive but genotypically negative isolates were categorized as AmpC producers as the performed PCR did not screen for all existing resistance genes.

All three phenotypic ESBL-producing E. coli strains isolated from the control group were screened for CTX-M genes. Two phenotypic AmpC isolates were screened for genes encoding AmpC β-lactamases. One isolate (33.3%) carried a resistance gene belonging to CTX-M group 1, and both isolates were positive for a mutation in the AmpC promoter region (Fig. 1).

MICs of 20 antimicrobial drugs were determined for all 196 ESBL-producing E. coli isolates (Table 3). All isolates showed susceptibility to carbapenems, except for one ertapenem-resistant isolate from a beef cattle farm. A significant difference in susceptibility of isolates associated with different farm types could be detected: ESBL-producing E. coli from beef cattle farms were significantly less likely to be resistant against aztreonam (P = 0.030; RR = 1.29; CI, 1.0 to 1.7), gentamicin (P = 0.0014; RR = 3.33; CI, 1.3 to 8.3), tobramycin (P = 0.008; RR = 2.12; CI, 1.1 to 4.1), ciprofloxacin (P < 0.001; RR = 3.82; CI, 1.5 to 9.5), and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (P = 0.017; RR = 1.55; CI, 1.0 to 2.4) than isolates from mixed farms. Resistance to fosfomycin, though, was found more often on beef cattle farms (P = 0.008; RR = 19.62; CI, 2.1 to 181.6) than mixed farms.

Table 3.

Resistance patterns of bovine ESBL-producing E. coli isolates

| Antimicrobial(s) | No. (%) of isolates from: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed dairy and beef cattle farms (n = 170) |

Beef cattle farms (n = 26) |

|||||

| Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant | Susceptible | Intermediate | Resistant | |

| Ampicillin | 0 | 0 | 170 (100) | 0 | 0 | 26 (100) |

| Cefazolin | 0 | 0 | 170 (100) | 0 | 0 | 26 (100) |

| Cefuroxime | 0 | 0 | 170 (100) | 0 | 0 | 26 (100) |

| Cephalexin | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 169 (99.4) | 1 (3.9) | 0 | 25 (96.2) |

| Cefotaxime | 1 (0.6) | 7 (4.1) | 162 (95.3) | 0 | 4 (15.4) | 22 (84.6) |

| Ceftazidime | 33 (19.4) | 82 (48.2) | 55 (32.4) | 10 (38.5) | 10 (38.5) | 6 (23.1) |

| Imipenem | 170 (100) | 0 | 0 | 26 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Meropenem | 170 (100) | 0 | 0 | 26 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Ertapenem | 170 (100) | 0 | 0 | 25 (96.2) | 0 | 1 (3.9) |

| Aztreonam | 1 (0.6) | 26 (15.3) | 143 (84.1) | 1 (3.9) | 8 (30.8) | 17 (65.4) |

| Nitrofurantoin | 164 (96.5) | 0 (0) | 6 (3.5) | 23 (88.5) | 0 | 3 (11.5) |

| Gentamicin | 78 (45.9) | 5 (2.9) | 87 (51.2) | 22 (84.6) | 0 | 4 (15.4) |

| Tobramycin | 73 (42.9) | 0 | 97 (57.1) | 19 (73.1) | 0 | 7 (26.9) |

| Amikacin | 169 (99.4) | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 26 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 68 (40.0) | 2 (1.2) | 100 (58.8) | 22 (84.6) | 0 | 4 (15.4) |

| Trimethoprim-sulfomethoxazole | 48 (28.2) | 0 | 122 (71.8) | 14 (53.8) | 0 | 12 (46.2) |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 141 (82.9) | 5 (2.9) | 24 (14.1) | 22 (84.6) | 0 | 4 (15.4) |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 80 (47.1) | 0 | 90 (52.9) | 12 (46.2) | 0 | 14 (53.8) |

| Colistin | 170 (100) | 0 | 0 | 26 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Fosfomycin | 169 (99.4) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 23 (88.5) | 0 | 3 (11.5) |

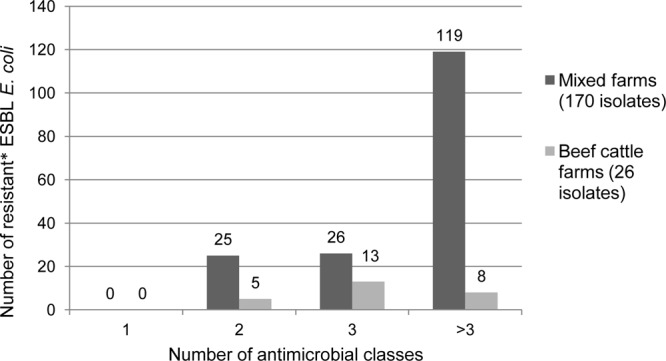

Of the 196 isolates, 30 (15.3%) were resistant to two substance classes (Fig. 2). If an isolate was classified as intermediate for a group, it was categorized as resistant in this type of analysis. Altogether, 39 isolates (19.9%) showed resistance against three substance classes. Most of the isolates (127 [64.8%]) were multiresistant (resistant to three or more substance classes).

Fig 2.

ESBL-producing E. coli isolates resistant to one or more classes of antimicrobial substances. The asterisk indicates that if an isolate was classified as intermediate for a group, it was categorized as resistant.

Survey.

The survey showed that 30 of 30 (100%) mixed farms and 14 of 15 (93.3%) beef cattle farms used antimicrobials for the last 6 months; 96.7% of mixed farms and 71.4% of beef cattle farms administered β-lactam antimicrobials. Furthermore, the data showed that ESBL-producing E. coli strains were significantly more often detected in fecal samples from calf groups treated with antimicrobials (P = 0.041) than in untreated groups: ESBL-producing E. coli-positive fecal samples were detected on 24 of 30 farms, with 22 farms reporting common use of antimicrobials, no farms reporting sporadic use, and 2 farms reporting no use of antimicrobials in the calf group. ESBL-producing E. coli-negative fecal samples from the calf group were found on 6 of the 30 farms, where 3 farms reported common use of antimicrobials, 1 farm reported sporadic use, and 2 farms reported no use of antimicrobials in this group.

A relationship between feeding waste milk (which may contain remnants of antibiotics) to calves and a higher detection rate of ESBL-producing E. coli in fecal samples from this group was statistically not significant (P = 0.055; median for calves without waste milk, 0.33; median for calves with waste milk, 0.83).

On mixed farms, an association could be demonstrated between the number of animals on a farm and ESBL-producing E. coli-positive samples from cows: positive samples could be detected more often from farms with a higher number of animals on the farm (P = 0.025; median number of animals on farms where the cow group is positive for ESBL-producing E. coli, 155; median number of animals on farms where the cow group is negative for ESBL-producing E. coli, 98) and a higher number of animals in the cow group (P = 0.019; median number of cows on farms where the cow group is positive for ESBL-producing E. coli, 60; median number of cows on farms where the cow group is negative for ESBL-producing E. coli, 40). Furthermore, the data showed that positive fecal samples from beef cattle were more likely to be found on farms purchasing greater numbers of animals for beef cattle (P = 0.045; median number of purchased beef cattle from farms where fecal samples obtained from the beef cattle group were positive for ESBL-producing E. coli, 20; median number of purchased beef cattle from farms where no fecal samples from the beef cattle group were positive for ESBL-producing E. coli, 10).

On beef cattle farms the survey showed similar findings: on farms purchasing higher numbers of animals, ESBL-producing E. coli was more likely to be detected (P = 0.022; median number of purchased animals on farms with ESBL-producing E. coli, 130; median number of animals on farms without ESBL-producing E. coli, 19) in at least one sample.

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to assess the status of ESBL-producing E. coli on cattle farms typical for Bavaria and to elucidate possible risk factors for their spread. Focus was laid on herd and group status, and therefore, individual animal aspects were not evaluated. The ESBL-producing E. coli status was defined at the group or herd level, where this technique was suggested in cattle (21). The results show that ESBL-producing E. coli strains were much more frequently detected than expected on Bavarian mixed and beef cattle farms. They could be detected on 86.7% of all farms, mixed farms being positive more often than beef cattle farms. The prevalences of ESBL-producing E. coli-positive fecal samples on mixed farms were 39.6% and 18.9% on beef cattle farms. This seems to be an increase, as such strains have only sporadically been described in Germany before (16). However, this could also be due to differences in the detection methods as in this study ESBL-producing E. coli strains were selected using enrichment and selective media (MCA containing cefotaxime). Guerra et al. (16), however, did not test samples from field trials, but received E. coli isolates from different labs wanting them to be typed. These isolates have not been selected with special media, which has an important effect on the results. Other European studies reported common occurrence of ESBL-producing E. coli in cattle in Switzerland (22), France (23), Denmark (24), and the United Kingdom (8).

This high prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli could be based on using enrichment procedures for selection. With 92 enriched fecal and dust samples being positive for ESBL-producing E. coli compared to 41 positive samples (44.6%) without enrichment, ESBL-producing E. coli strains could be isolated more than twice as often using enrichment procedures. Even small numbers of E. coli strains were more likely to be found using the enrichment media. Therefore, we suggest using an enrichment procedure for the screening of ESBL that is especially recommended for dust samples.

An overall significant difference in prevalences exists between mixed and beef cattle farms using antimicrobials and the control group not having used antimicrobials for at least half a year (P < 0.001; RR = 5.35; CI, 1.8 to 16.1), although the control group consisted of another farm type for technical reasons. Different studies described that the use of antimicrobials exerts a dominant selective pressure and may favor the spread of resistance genes (25–27). In this study, 100% (30/30) of mixed farms and 93.3% (14/15) of beef cattle farms used antimicrobials for the last 6 months. β-Lactam antimicrobials have been used on 96.7% of mixed farms and on 71.4% of beef cattle farms. We found ESBL-producing E. coli even on farms that did not use antimicrobials of this group, but the use of non-β-lactam antimicrobials can select for ESBL resistance genes as well, since the resistance determinants against cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, tetracycline, and sulfonamides are often situated on the same plasmid (28). The use of any of these antimicrobials can coselect for all other ones. Plasmids that carry antimicrobial resistance genes can also carry genes mediating resistance against disinfectants, heavy metal tolerance, virulence, and metabolic functions and, therefore, could be coselected (29).

The overall prevalence of ESBL-producing E. coli was much higher in calves (55.7%) than in cows (37.3%) (P = 0.002; RR = 1.49; CI, 1.2 to 1.9). This is consistent with recently published studies in Great Britain (30, 31). ESBL-producing E. coli-positive fecal samples were more often recovered from calves on farms using antimicrobials (P = 0.041). Using antimicrobials can potentially contribute to the maintenance and spread of ESBL. Berge et al. (32), though, observed highly resistant E. coli in dairy heifers not exposed to antimicrobials. They concluded that an individual antibiotic therapy could lead to selective pressure enough to establish a resistant gene pool in the farm-level bacterial population.

The survey data showed that calves being fed waste milk (P = 0.055; median, 0.33; SE, 0.83) harbor more ESBL-producing E. coli-positive fecal samples, however, not significantly. The observation of the effect of feeding waste milk (which may contain antibiotics at low concentrations) to calves suggests that this practice may act as a selection pressure and may be an advantage for bacteria with resistance to antimicrobials. Consistent proposals have been stated in a previous study (32) where Berge et al. hypothesized that feeding waste milk may play a role in selecting resistant bacterial populations on farms.

We screened all 196 phenotypic ESBL-producing E. coli isolates for the blaCTX-M genes and found that 93.4% of isolates were positive. This indicates that blaCTX-M genes are present on most Bavarian mixed and beef cattle farms. The genes are frequently responsible for resistance to extended-spectrum and very-broad-spectrum cephalosporins in Enterobacteriaceae in Europe, group 1 (CTX-M-1 and -15) being the predominant bla genes in western and northern European countries (33). CTX-M-9 group has been isolated from animals in Spain (34), France (35), and the United Kingdom (36), whereas CTX-M group 2 has been mainly described in South America and Japan (37). These findings are consistent with the observation in this study as blaCTX-M-1 group genes were predominantly detected, as were, sporadically, blaCTX-M genes belonging to groups 2 and 9.

In addition, 48 phenotypic AmpC E. coli isolates were screened for the presence of mutations of the promoter region and plasmid-mediated AmpC. A predominance of mutation of the promoter region was found; however, five isolates with blaCMY-2 were yielded from three beef cattle farms. To our knowledge, this is the first time that blaCMY-2 has been detected in cattle in Germany. Before, blaCMY-2 was described in Salmonella spp. from poultry only (38). However, studies from different European countries show that blaCMY-2 genes are well described in cattle (23, 39–41).

Conclusion.

We observed that ESBL-producing E. coli strains are commonly found on Bavarian dairy and beef cattle farms, recognizing that our study provides data only for a circumscribed area in Germany. However, the results were consistent with other European studies. There is a paucity of studies that show a countrywide prevalence in Germany and other European countries. Additional nationwide surveys would be necessary to identify the possible spread of ESBL-producing E. coli, its transmission dynamics, and risk factors. Different countries, including Germany, have already started screening for ESBL-producing E. coli on a wider scale, but final results are not yet available.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was conducted within the RESET joint research project (http://www.reset-verbund.de), funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research.

We thank the participating farmers for their cooperation and assistance in this study and the veterinarians who established contact with the farmers. We give special thanks to the technicians of the Bavarian Health and Food Safety Authority, Oberschleissheim, for technical assistance, and we also thank Giuseppe Valenza (Bavarian Health and Food Safety Authority, Erlangen) for screening and typing some E. coli isolates for blaTEM and blaSHV genes. We are grateful for advice on the study design from Reinhard Straubinger of the Institute for Infectious Diseases and Zoonoses, Department of Veterinary Sciences, LMU Munich.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 1 March 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. De Champs C, Chanal C, Sirot D, Baraduc R, Romaszko JP, Bonnet R, Plaidy A, Boyer M, Carroy E, Gbadamassi MC, Laluque S, Oules O, Poupart MC, Villemain M, Sirot J. 2004. Frequency and diversity of class A extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in hospitals of the Auvergne, France: a 2 year prospective study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54: 634– 639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pitout JD, Gregson DB, Campbell L, Laupland KB. 2009. Molecular characteristics of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates causing bacteremia in the Calgary Health Region from 2000 to 2007: emergence of clone ST131 as a cause of community-acquired infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53: 2846– 2851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carattoli A, Lovari S, Franco A, Cordaro G, Di Matteo P, Battisti A. 2005. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Escherichia coli isolated from dogs and cats in Rome, Italy, from 2001 to 2003. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49: 833– 835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Costa D, Poeta P, Brinas L, Saenz Y, Rodrigues J, Torres C. 2004. Detection of CTX-M-1 and TEM-52 beta-lactamases in Escherichia coli strains from healthy pets in Portugal. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54: 960– 961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schink A-K, Kadlec K, Schwarz S. 2011. Analysis of blaCTX-M-carrying plasmids from Escherichia coli isolates collected in the BfT-GermVet study. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77: 7142– 7146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meunier D, Jouy E, Lazizzera C, Kobisch M, Madec JY. 2006. CTX-M-1- and CTX-M-15-type beta-lactamases in clinical Escherichia coli isolates recovered from food-producing animals in France. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 28: 402– 407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brinas L, Moreno MA, Zarazaga M, Porrero C, Saenz Y, Garcia M, Dominguez L, Torres C. 2003. Detection of CMY-2, CTX-M-14, and SHV-12 beta-lactamases in Escherichia coli fecal-sample isolates from healthy chickens. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47: 2056– 2058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Horton RA, Randall LP, Snary EL, Cockrem H, Lotz S, Wearing H, Duncan D, Rabie A, McLaren I, Watson E, La Ragione RM, Coldham NG. 2011. Fecal carriage and shedding density of CTX-M extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in cattle, chickens, and pigs: implications for environmental contamination and food production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77: 3715– 3719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duan RS, Sit TH, Wong SS, Wong RC, Chow KH, Mak GC, Yam WC, Ng LT, Yuen KY, Ho PL. 2006. Escherichia coli producing CTX-M beta-lactamases in food animals in Hong Kong. Microb. Drug Resist. 12: 145– 148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wittum TE, Mollenkopf DF, Daniels JB, Parkinson AE, Mathews JL, Fry PR, Abley MJ, Gebreyes WA. 2010. CTX-M-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases present in Escherichia coli from the feces of cattle in Ohio, United States. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 7: 1575– 1579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Doi Y, Paterson DL, Egea P, Pascual A, Lopez-Cerero L, Navarro MD, Adams-Haduch JM, Qureshi ZA, Sidjabat HE, Rodriguez-Bano J. 2010. Extended-spectrum and CMY-type beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in clinical samples and retail meat from Pittsburgh, USA and Seville, Spain. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16: 33– 38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jensen LB, Hasman H, Agerso Y, Emborg HD, Aarestrup FM. 2006. First description of an oxyimino-cephalosporin-resistant, ESBL-carrying Escherichia coli isolated from meat sold in Denmark. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 57: 793– 794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Carattoli A. 2008. Animal reservoirs for extended spectrum beta-lactamase producers. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14(Suppl 1):117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Winokur PL, Vonstein DL, Hoffman LJ, Uhlenhopp EK, Doern GV. 2001. Evidence for transfer of CMY-2 AmpC beta-lactamase plasmids between Escherichia coli and Salmonella isolates from food animals and humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45: 2716– 2722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oppegaard H, Steinum TM, Wasteson Y. 2001. Horizontal transfer of a multi-drug resistance plasmid between coliform bacteria of human and bovine origin in a farm environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67: 3732– 3734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guerra B, Avsaroglu MD, Junker E, Schroeter A, Beutin L, Helmuth R. 2007. P1013 detection and characterisation of ESBLs in German Escherichia coli, isolated from animal, foods, and human origin between 2001–2006. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 29(Suppl 2):S270–S271 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Birkett CI, Ludlam HA, Woodford N, Brown DF, Brown NM, Roberts MT, Milner N, Curran MD. 2007. Real-time TaqMan PCR for rapid detection and typing of genes encoding CTX-M extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. J. Med. Microbiol. 56: 52– 55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Polsfuss S, Bloemberg GV, Giger J, Meyer V, Bottger EC, Hombach M. 2011. Practical approach for reliable detection of AmpC beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49: 2798– 2803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grobner S, Linke D, Schutz W, Fladerer C, Madlung J, Autenrieth IB, Witte W, Pfeifer Y. 2009. Emergence of carbapenem-non-susceptible extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates at the university hospital of Tubingen, Germany. J. Med. Microbiol. 58: 912– 922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Caroff N, Espaze E, Gautreau D, Richet H, Reynaud A. 2000. Analysis of the effects of −42 and −32 ampC promoter mutations in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli hyperproducing AmpC. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 45: 783– 788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wagner BA, Dargatz DA, Morley PS, Keefe TJ, Salman MD. 2003. Analysis methods for evaluating bacterial antimicrobial resistance outcomes. Am. J. Vet. Res. 64: 1570– 1579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Geser N, Stephan R, Hachler H. 2012. Occurrence and characteristics of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Enterobacteriaceae in food producing animals, minced meat and raw milk. BMC Vet. Res. 8: 21 doi:10.1186/1746-6148-8-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Madec JY, Lazizzera C, Chatre P, Meunier D, Martin S, Lepage G, Menard MF, Lebreton P, Rambaud T. 2008. Prevalence of fecal carriage of acquired expanded-spectrum cephalosporin resistance in Enterobacteriaceae strains from cattle in France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:1566– 1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. DANMAP 2012. DANMAP 2011—Use of antimicrobial agents and occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from food animals, food and humans in Denmark. http://www.danmap.org/Downloads/∼/media/Projekt%20sites/Danmap/DANMAP%20reports/Danmap_2011.ashx Last accessed January 2013

- 25. Berge AC, Moore DA, Sischo WM. 2006. Field trial evaluating the influence of prophylactic and therapeutic antimicrobial administration on antimicrobial resistance of fecal Escherichia coli in dairy calves. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72: 3872– 3878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tragesser LA, Wittum TE, Funk JA, Winokur PL, Rajala-Schultz PJ. 2006. Association between ceftiofur use and isolation of Escherichia coli with reduced susceptibility to ceftriaxone from fecal samples of dairy cows. Am. J. Vet. Res. 67: 1696– 1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. EFSA 2011. Scientific opinion on the public health risks of bacterial strains producing extended-spectrum β-lactamases and/or AmpC β-lactamases in food and food-producing animals. EFSA J. 9: 1– 95 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jacoby GA, Sutton L. 1991. Properties of plasmids responsible for production of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35: 164– 169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barbosa TM, Levy SB. 2000. The impact of antibiotic use on resistance development and persistence. Drug Resist. Updat. 3: 303– 311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Watson E, Jeckel S, Snow L, Stubbs R, Teale C, Wearing H, Horton R, Toszeghy M, Tearne O, Ellis-Iversen J, Coldham N. 2012. Epidemiology of extended spectrum beta-lactamase E. coli (CTX-M-15) on a commercial dairy farm. Vet. Microbiol. 154: 339– 346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liebana E, Batchelor M, Hopkins KL, Clifton-Hadley FA, Teale CJ, Foster A, Barker L, Threlfall EJ, Davies RH. 2006. Longitudinal farm study of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-mediated resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44: 1630– 1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Berge AC, Atwill ER, Sischo WM. 2005. Animal and farm influences on the dynamics of antibiotic resistance in faecal Escherichia coli in young dairy calves. Prev. Vet. Med. 69: 25– 38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Coque TM, Baquero F, Canton R. 2008. Increasing prevalence of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Euro Surveill. 13:19044 (Erratum, 13:19051.) http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=19044 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brinas L, Moreno MA, Teshager T, Saenz Y, Porrero MC, Dominguez L, Torres C. 2005. Monitoring and characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in Escherichia coli strains from healthy and sick animals in Spain in 2003. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49: 1262– 1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Valat C, Auvray F, Forest K, Metayer V, Gay E, Peytavin de Garam C, Madec JY, Haenni M. 2012. Phylogenetic grouping and virulence potential of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli strains in cattle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78: 4677– 4682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Snow LC, Wearing H, Stephenson B, Teale CJ, Coldham NG. 2011. Investigation of the presence of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in the North Wales and West Midlands areas of the UK in 2007 to 2008 using scanning surveillance. Vet. Rec. 169: 656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Canton R, Coque TM. 2006. The CTX-M beta-lactamase pandemic. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:466– 475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rodriguez I, Barownick W, Helmuth R, Mendoza MC, Rodicio MR, Schroeter A, Guerra B. 2009. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases and AmpC β-lactamases in ceftiofur-resistant Salmonella enterica isolates from food and livestock obtained in Germany during 2003–07. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64: 301– 309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Endimiani A, Rossano A, Kunz D, Overesch G, Perreten V. 2012. First countrywide survey of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli from broilers, swine, and cattle in Switzerland. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 73: 31– 38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Batchelor M, Clifton-Hadley FA, Stallwood AD, Paiba GA, Davies RH, Liebana E. 2005. Detection of multiple cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli from a cattle fecal sample in Great Britain. Microb. Drug Resist. 11: 58– 61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wasyl D, Hasman H, Cavaco LM, Aarestrup FM. 2012. Prevalence and characterization of cephalosporin resistance in nonpathogenic Escherichia coli from food-producing animals slaughtered in Poland. Microb. Drug Resist. 18: 79– 82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]