Abstract

Corynebacterium glutamicum is particularly known for its industrial application in the production of amino acids. Amino acid overproduction comes along with a high NADPH demand, which is covered mainly by the oxidative part of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). In previous studies, the complete redirection of the carbon flux toward the PPP by chromosomal inactivation of the pgi gene, encoding the phosphoglucoisomerase, has been applied for the improvement of C. glutamicum amino acid production strains, but this was accompanied by severe negative effects on the growth characteristics. To investigate these effects in a genetically defined background, we deleted the pgi gene in the type strain C. glutamicum ATCC 13032. The resulting strain, C. glutamicum Δpgi, lacked detectable phosphoglucoisomerase activity and grew poorly with glucose as the sole substrate. Apart from the already reported inhibition of the PPP by NADPH accumulation, we detected a drastic reduction of the phosphotransferase system (PTS)-mediated glucose uptake in C. glutamicum Δpgi. Furthermore, Northern blot analyses revealed that expression of ptsG, which encodes the glucose-specific EII permease of the PTS, was abolished in this mutant. Applying our findings, we optimized l-lysine production in the model strain C. glutamicum DM1729 by deletion of pgi and overexpression of plasmid-encoded ptsG. l-Lysine yields and productivity with C. glutamicum Δpgi(pBB1-ptsG) were significantly higher than those with C. glutamicum Δpgi(pBB1). These results show that ptsG overexpression is required to overcome the repressed activity of PTS-mediated glucose uptake in pgi-deficient C. glutamicum strains, thus enabling efficient as well as fast l-lysine production.

INTRODUCTION

The Gram-positive, nonpathogenic bacterium Corynebacterium glutamicum is generally known for its employment in the large-scale industrial production of the amino acids l-glutamate and l-lysine (1). Furthermore, C. glutamicum strains for the efficient production of other amino acids such as l-valine have been developed (2, 3). The syntheses of these amino acids require reducing power in the form of NADPH. For example, synthesis of 1 mol l-lysine by either one of the two pathways present in C. glutamicum requires 4 mol of NADPH (4–6), and the synthesis of 1 mol of l-valine requires at least 2 mol of NADPH (7, 8). Based on the stoichiometry of the metabolic pathways in C. glutamicum, elementary flux mode analyses indicated that efficient regeneration of the cofactor NADPH is indeed essential to obtain theoretical maximal yields for l-lysine (yield of product on substrate [YP/S], 0.82 mol Lys/mol Glc [9]) and l-valine (YP/S, 0.86 mol Val/mol Glc [10]). C. glutamicum possesses four enzymes for the regeneration of NADPH from NADP: glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Zwf) and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (Gnd) of the oxidative part of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) (11–13), isocitrate dehydrogenase of the tricarboxylic acid cycle (14, 15), and the malic enzyme MalE (16, 17). The last enzyme was shown to catalyze NADPH regeneration in C. glutamicum in a metabolic cycle formed by pyruvate carboxylase/phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) carboxylase, malate dehydrogenase, and MalE (16, 18, 19). For l-lysine production, metabolic flux studies revealed a correlation between product yield and carbon flux through the PPP (4, 20–23), indicating that NADPH regeneration by Zwf and Gnd might be crucial for l-lysine production. Indeed, increased flux through the PPP by overexpression of fbp and/or zwf, encoding fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase and Zwf, respectively, significantly improved C. glutamicum l-lysine yields (16, 24, 25). Also, the straightforward approach to direct carbon flux entirely to the PPP by abolishing glycolysis through the deletion of pgi, which encodes the first glycolysis-specific enzyme phosphoglucoisomerase (Pgi), improved NADPH supply and therefore also the substrate-specific product yields of C. glutamicum l-lysine and l-valine production strains (3, 10, 26). However, the growth, substrate consumption, and productivity of pgi-deficient C. glutamicum strains are drastically reduced in cultivations with glucose as the sole carbon source (10, 26). This phenotype of C. glutamicum pgi deletion mutants is thought to be triggered by high intracellular NADPH concentrations (10): in the case of NADPH, excess NADPH-forming enzymes such as Zwf and Gnd of the PPP are inhibited (KiNADPH of Zwf, 61 μM; KiNADPH of Gnd, 103 μM [11]), which in the case of these two enzymes would probably limit the flux through the PPP and therefore also restrict growth of Pgi-deficient C. glutamicum strains.

For Pgi-deficient Escherichia coli strains cultivated with glucose, severe growth defects also have been described (27, 28), which come along with imbalances of NADPH metabolism (29, 30). Deficits in NADPH regeneration can be ameliorated in E. coli by the action of the soluble pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase UdhA, which catalyzes the reversible transfer of reducing equivalents between NAD and NADP pools (31). Indeed, increased expression of udhA improves growth of pgi-deficient E. coli strains on glucose (32, 33). As the underlying mechanism for the growth deficits and reduced glucose consumption of E. coli pgi deletion strains cultivated on glucose, a complex regulatory cascade to reduce glucose uptake in response to sugar phosphate stress was identified (34, 35). In E. coli, glucose uptake and phosphorylation are accomplished by the ptsG-encoded EIICBGlc of the phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system (PTS) (36). When in pgi-deficient E. coli cells, glucose 6-phosphate abnormally accumulates, synthesis of the small RNA (sRNA) SgrS (sugar transport-related sRNA) is induced by the transcriptional activator SgrR (37). SgrS binds to the ptsG transcript through base pairing at the translation initiation region and by this means inhibits ptsG translation (35, 38). Furthermore, SgrS forms with Hfq and RNase E a specific ribonucleoprotein complex which catalyzes the rapid degradation of ptsG mRNA (34, 39). In addition, SgrS encodes the small polypeptide SgrT, which presumably acts as an inhibitor to stop glucose uptake through preexisting EIICBGlc. (35). Taken together, these observations show that PTS-mediated glucose uptake is downregulated in E. coli Δpgi to prevent glucose 6-phosphate accumulation.

In C. glutamicum, glucose is imported and phosphorylated mainly via the PTS, requiring the ptsG-encoded glucose-specific EIIABCGlc component and the two general components EI and HPr (reviewed in reference 40). PTS-independent glucose utilization was recently also described in C. glutamicum: in PTS-deficient strains, glucose uptake is mediated by the two inositol permeases (IolT1 and IolT2), and subsequently phosphorylation is catalyzed by the two glucose kinases Glk and PpgK (41, 42). So far, effects on glucose uptake caused by the blockage of the upper part of glycolysis have not been studied in C. glutamicum.

In the present study, we deleted the pgi gene (cg0973) in C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 to study PTS-mediated glucose uptake in cells lacking the upper part of glycolysis. We show that the expression of ptsG is abolished and the activity of the glucose-specific PTS is subsequently very low in C. glutamicum Δpgi. Based on these observations, we improved the productivity of the l-lysine production strain C. glutamicum DM1729 Δpgi by plasmid-encoded overexpression of ptsG.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microorganisms and cultivation conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. For plasmid construction, E. coli DH5α was used and cultured in lysogeny broth complex medium (LB) (43). Precultivation of C. glutamicum and cultivation of E. coli were carried out in LB. For the main cultures of C. glutamicum, the cells of an overnight preculture were washed with 0.9% (wt/vol) NaCl and then inoculated into LB complex medium or into CGXII minimal medium (44) containing glucose at concentrations indicated in Results. For selection of clones carrying the overexpression plasmids pEKEx3 and pBB1 and their derivatives, spectinomycin (100 μg ml−1) and chloramphenicol (6 μg ml−1) were used, respectively. For induction, up to 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to the medium. Quantifications of glucose and l-lysine concentrations in culture supernatants were performed by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described previously (45, 46).

Table 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| DH5α | F− thi-1 endA1 hsdR17(r− m−) supE44 ΔlacU169 (ϕ80lacZΔM15) recA1 gyrA96 relA1 | 61 |

| MG1655 | F− λ− ilvG rfb-50 rph-1 | 62 |

| C. glutamicum strains | ||

| ATCC 13032 (WT) | Wild-type strain | American Type Culture Collection |

| Δpgi | In-frame deletion of pgi gene (cg0973) of C. glutamicum WT | This work |

| Δpgi IMptsG | Inactivation of ptsG (cg1537) in C. glutamicum Δpgi | This work |

| DM1729 | l-Lysine-producing strain (pycP458S, homV59A, lysCT311I) | 16 |

| DM1729 Δpgi | In-frame deletion of pgi gene (cg0973) of C. glutamicum DM1729 | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pK19mobsacB | Kanr, mobilizable E. coli vector for the construction of insertion and deletion mutants of C. glutamicum (oriV, sacB, lacZα) | 63 |

| pK19mobsacB-Δpgi | Kanr, pK19mobsacB with the deletion construct for cg0973 | 3 |

| pDrive-IMptsG | Kanr Ampr, E. coli cloning vector (lacZα, orif1, ori-pUC) carrying internal region of ptsG (1537) for inactivation | 41 |

| pBB1 | Chlr, C. glutamicum/E. coli shuttle vector (Ptac lacIq; pBL1, OriVC.g., OriVE.c.) | 50 |

| pBB1-ptsG | Derived from pBB1, for constitutive expression of ptsG (cg1537) of C. glutamicum | 50 |

| pEKEx3 | Specr; C. glutamicum/E. coli shuttle vector (Ptac lacIq; pBL1, OriVC.g., OriVE.c.) | 49 |

| pEKEx3-pgi | Derived from pEKEx3, for regulated expression of pgi (cg0973) of C. glutamicum | This work |

| pEKEx3-udhA | Derived from pEKEx3, for regulated expression of udhA (b3962) of E. coli | This work |

DNA preparation, manipulation, and transformation.

Standard procedures were employed for plasmid isolation and for molecular cloning and transformation of E. coli, as well as for electrophoresis (43). Isolation of plasmids and chromosomal DNA of C. glutamicum was performed as described previously (47). Transformation of C. glutamicum was performed by electroporation as described by Tauch et al. (48). PCR experiments were performed in a Flexcycler (Analytik Jena) with Taq DNA polymerase (MBI Fermentas) or Phusion DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs) with oligonucleotides obtained from Eurofins MWG Operon (listed in Table 2). All restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, and shrimp alkaline phosphatase were obtained from New England BioLabs and used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Name | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Purpose, restriction site |

|---|---|---|

| pgiΔVer-for | CACTCATTGGTCGTGATG | Verification of pgi deletion by PCR |

| pgiΔVer-rev | GGAACGACACCAGATAAG | Verification of pgi deletion by PCR |

| pgi-SB-for | TGTACACCGCCAAAGACC | Probe for Southern blot analyses |

| pgi-SB-rev | CTTGGCGTCCTCCTTAAC | Probe for Southern blot analyses |

| IMptsG-Ver-fw | TCGTAACGGCGATCCTC | Verification of ptsG inactivation |

| M13-FP | TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGT | Verification of ptsG inactivation |

| udhA-fw | GCTCTAGAGAAAGGAGGCCCTTCAGATGCCACATTCCTACGATTACG | pEKEX3-udhA, XbaI |

| udhA-rv | GCTCTAGATTAAAACAGGCGGTTTAAACCG | pEKEX3-udhA, XbaI |

| pgi-fw | GAGGATCCGAAAGGAGGCCCTTCAGATGGCGGACATTTCGACCAC | pEKEX3-pgi, BamHI |

| pgi-rv | GAGGATCCCTACCTATTTGCGCGGTACCAC | pEKEX3-pgi, BamHI |

| ptsG-probe-fw | CAAACTGACGACGACATC | ptsG probe for dot blot analyses |

| ptsG-probe-T7-rv | GGGCCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGTGGCAGGAAGTAGAAGAC | ptsG probe for dot blot analyses |

| 16S-probe-fw | GAATTCGATGCACCGAGTGGAAGT | 16S RNA gene probe for dot blot analyses |

| 16S-probe-T7-rv | GGGCCCTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGGGTACCGAACCAGTGTGGCACATC | 16S RNA gene probe for dot blot analyses |

Restriction sites in the oligonucleotides are bold, T7 promoter sequences for in vitro transcription and start codons are underlined, and ribosome binding sites are italicized.

Construction of expression vectors.

For IPTG-inducible overexpression, vector pEKEx3 (49) was used, while pBB1 (50) was used for constitutive expression. Genes were amplified via PCR from genomic DNA of wild-type (WT) C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 or E. coli MG1655 using the oligonucleotide primers listed in Table 2. For overexpression of pgi, it was amplified via PCR from genomic DNA of WT C. glutamicum using oligonucleotide primers pgi-fw and pgi-rv. For amplification of udhA (b3962) from E. coli, the oligonucleotide primers udhA-fw and udhA-rv were used. The PCR products of pgi and udhA were cloned blunt into SmaI-restricted vector pEKEx3, resulting in pEKEx3-pgi and pEKEx3-udhA. All plasmids used are listed in Table 1.

Construction of C. glutamicum mutant strains.

The in-frame deletion of pgi was constructed in WT C. glutamicum and C. glutamicum DM1729 using pK19mobsacB-Δpgi exactly as described previously (3). The deletion of pgi was verified by PCR using the primer pairs pgiΔVer-for and pgiΔVer-rev and/or by Southern blot analyses performed essentially as described previously (51). As the probe, a 509-bp fragment upstream of pgi was amplified from chromosomal DNA of WT C. glutamicum using primers pgi-SB-for and pgi-SB-rev. Labeling with digoxigenin-dUTP, hybridization, washing, and detection were conducted using the nonradioactive DNA labeling and detection kit and instructions from Roche Diagnostics. The labeled probe was hybridized to EcoRI-restricted and size-fractionated chromosomal DNA from WT C. glutamicum and potential Δpgi deletion mutants. The hybridization resulted in one signal of about 4.2 kb for WT C. glutamicum and one signal of about 5.8 kb for C. glutamicum Δpgi strains (data not shown). These sizes were expected for the WT strain and the pgi deletion mutant, respectively.

Inactivation of ptsG (cg1537) in C. glutamicum Δpgi was achieved by insertion mutagenesis using plasmid pDrive-IMptsG as previously described (41). Integration into the genome in the resulting strain, C. glutamicum Δpgi IMptsG was verified by PCR using primers ptsG-Ver-fw and M13-FP.

Measurement of enzyme activities.

Enzyme activities were measured in cell extracts which were prepared as described previously (49). Cells were inoculated from LB overnight cultures to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.5 in 50 ml LB, harvested by centrifugation (10 min, 4°C, 3,220 × g) at an OD600 of 4, washed in the respective buffer used for the enzyme assay, centrifuged again, and stored at −20°C until use. Enzyme activities were measured using a Shimadzu UV-1650 PC spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Duisburg, Germany). Protein concentrations were determined with the Bradford reagent using bovine serum albumin as an external standard. Pgi activity was measured spectrophotometrically in a coupled assay, following NADPH formation at λ = 340 nm at 30°C in final volume of 1 ml. The assay contained 50 mM triethanolamine (pH 7.2), 0.25 mM NADP, 2 mM fructose 6-phosphate, and 5 U yeast glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Transhydrogenase activity was measured as described by Park et al. (52).

[14C]glucose uptake studies.

C. glutamicum cells were grown to early exponential growth phase (3 h), harvested by centrifugation, washed twice with ice-cold CGXII medium, suspended to an OD600 of 2 with CGXII medium, and stored on ice until the measurement. Before the transport assay, cells were incubated for 3 min at 30°C; the reaction was started by addition of 100 μM [14C]glucose (specific activity, 250 μCi μmol−1; Moravek Biochemicals, Brea, CA). At given time intervals (15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 s), 200-μl samples were filtered through glass fiber filters (type F; Millipore, Eschborn, Germany) and washed twice with 2.5 ml of 100 mM LiCl. The radioactivity of the samples was determined using scintillation fluid (Rotiszinth; Roth, Germany) and a scintillation counter (LS 6500; Beckmann, Krefeld, Germany).

RNA techniques.

Isolation of total RNA from C. glutamicum cells was performed using the NucleoSpin RNAII kit (Macherey & Nagel); slot blot experiments were performed as described previously (53). For hybridization, digoxigenin (DIG)-11-dUTP-labeled gene-specific antisense RNA probes were prepared from PCR products (generated with oligonucleotides listed in Table 2) carrying the T7 promoter by in vitro transcription (1 h, 37°C) using T7 RNA polymerase (MBI Fermentas). For that purpose, about 6 μg of total RNA was transferred to a nylon membrane using a Minifold dot blotter (Schleicher and Schuell). RNA was bound to the membrane by careful vacuum suction (1,500 Pa). RNA was cross-linked to the membrane by means of UV irradiation at 125 J cm−2. Hybridization and detection steps were carried out according to the DIG application manual (Roche Applied Science). Chemiluminescence was detected via the charge-coupled device (CCD) camera of the LAS 1000 CH system (Fuji).

RESULTS

Deletion of pgi in C. glutamicum negatively affects growth and glucose utilization.

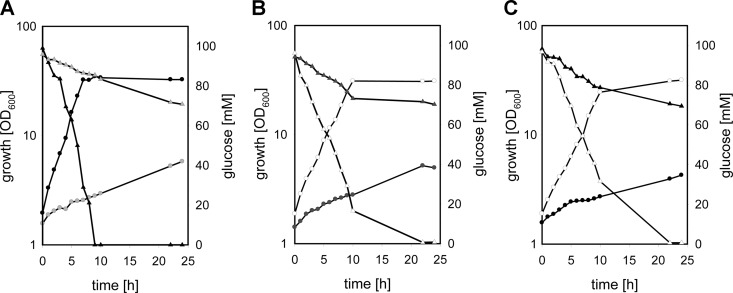

The pgi gene (cg0973) was inactivated by chromosomal deletion in C. glutamicum ATCC 13032, resulting in the strain designated C. glutamicum Δpgi. Cell extracts of the pgi deletion mutant completely lacked Pgi activity (<0.005 U mg−1), whereas WT cells showed an activity of 1.04 ± 0.23 U mg−1. Growth and substrate consumption of the mutant strain C. glutamicum Δpgi during cultivation in minimal medium with 2% glucose were analyzed (Fig. 1A). Both growth and substrate consumption were significantly slower in C. glutamicum Δpgi (growth rate, 0.05 ± 0.03 h−1) than in the parental WT C. glutamicum strain (growth rate, 0.38 ± 0.02 h−1). This growth phenotype of C. glutamicum Δpgi could at least partially be restored by the introduction of the plasmid pEKEx3-pgi (growth rate, 0.28 ± 0.02 h−1) (Fig. 1B), which carries the C. glutamicum pgi gene under the control of the IPTG-inducible Ptac promoter. In accordance, ectopic expression of pgi also restored Pgi activity in the C. glutamicum Δpgi background (0.32 ± 0.03 U mg−1). C. glutamicum Δpgi(pEKEx3), which carries the empty vector pEKEx3, showed neither improved growth (growth rate 0.05 ± 0.01 h−1; Fig. 1B) nor Pgi activity.

Fig 1.

Growth (circles) and glucose consumption (triangles) of WT C. glutamicum (black symbols) and C. glutamicum Δpgi (light gray symbols) (A), of C. glutamicum Δpgi(pEKEx3) (dark gray symbols) and C. glutamicum Δpgi(pEKEx3-pgi) (open symbols) (B), and of C. glutamicum Δpgi(pBB1) (filled symbols) and C. glutamicum Δpgi(pBB1-ptsG) (open symbols) (C) in CgC minimal medium initially containing 2% (wt/vol) glucose. One representative growth curve of at least three independent cultivations is shown;.

Heterologous expression of E. coli udhA in C. glutamicum Δpgi.

It was assumed that the feedback inhibition of both Zwf and Gnd by NADPH, and thus limitation of the oxidative part of the PPP, is responsible for the poor growth of pgi-deficient C. glutamicum strains with glucose as the sole carbon source (10, 11). C. glutamicum does not possess any transhydrogenases (54), which catalyze the oxidation of NADPH via the reduction of NAD or vice versa. To improve growth of C. glutamicum Δpgi on glucose, we heterologously expressed the udhA-encoded transhydrogenase of E. coli in the C. glutamicum Δpgi background. In fact, upon plasmid-encoded expression of E. coli udhA using plasmid pEKEx3-udhA, a transhydrogenase activity of 0.035 ± 0.003 U mg−1 was measured in extracts of C. glutamicum Δpgi(pEKEx3-udhA). However, growth of C. glutamicum Δpgi(pEKEx3-udhA) in minimal medium with glucose was only slightly improved (growth rate μ = 0.12 ± 0.04 h−1) compared to growth of C. glutamicum Δpgi(pEKEx3), which carries the empty plasmid. These results suggest that besides the NADPH-dependent feedback inhibition of Zwf and Gnd, additional reasons are responsible for the observed poor growth of Pgi-deficient C. glutamicum strains with glucose as the sole carbon source.

PTS-mediated glucose uptake and ptsG transcription are drastically reduced in C. glutamicum Δpgi.

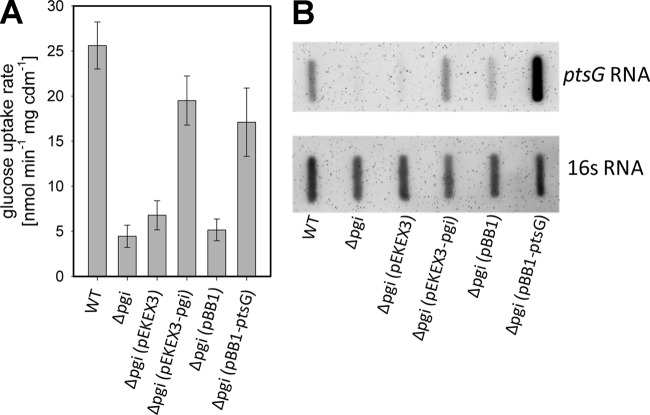

In E. coli, deletion of pgi triggers the glucose phosphate stress response, which includes degradation of the ptsG mRNA and results in reduced glucose uptake (4, 5; also see the introduction). As glucose uptake in pgi-deficient C. glutamicum strains has hitherto not been analyzed, we performed uptake assays with 14C-radiolabeled glucose. For C. glutamicum Δpgi cells cultivated on glucose, a glucose uptake rate of 4.4 ± 1.2 nmol min−1 mg cells dry matter (cdm)−1 was determined, which corresponds to about one-fifth of the rate determined for the parental WT C. glutamicum strain (25.6 ± 2.6 nmol min−1 mg cdm−1) (Fig. 2A). Glucose uptake was also found to be significantly reduced in C. glutamicum Δpgi cells cultivated in TY complex medium compared to in WT C. glutamicum (8.6 ± 0.6 nmol min−1 mg cdm−1 and 20.3 ± 0.4 nmol min−1 mg cdm−1, respectively); however, the effect on glucose uptake in cells from complex medium was less severe than that in cells cultivated in minimal medium (Fig. 2A). Glucose uptake was restored in C. glutamicum Δpgi(pEKEx3-pgi) cells cultivated in minimal medium with glucose (19.5 ± 2.7 nmol min−1 mg cdm−1), almost reaching the level in the parental strain. As expected, glucose uptake in C. glutamicum Δpgi(pEKEx3) remained drastically reduced, at a rate of 6.7 ± 1.6 nmol min−1 mg cdm−1.

Fig 2.

Analyses of [14C]glucose uptake (A) and ptsG transcription (B) in WT C. glutamicum, C. glutamicum Δpgi, C. glutamicum Δpgi(pEKEx3), C. glutamicum Δpgi(pEKEx3-pgi), C. glutamicum Δpgi(pBB1), and C. glutamicum Δpgi(pBB1-ptsG) after short-time cultivation (3 h) in CgC minimal medium containing 1% (wt/vol) glucose. The glucose uptake data represent mean values and standard deviations of three independent measurements from at least three independent cultivations. The ptsG and 16S RNA levels were monitored in the RNA hybridization experiments with DIG-labeled antisense RNA probes, and results from one representative experiment of at least three independent RNA hybridization experiments are shown.

Furthermore, expression of ptsG was analyzed in Pgi-deficient strains by RNA slot blotting using a ptsG-specific RNA probe after short-term cultivation (for 3 h) in minimal medium with glucose. As shown in Fig. 2B, only residual amounts of ptsG transcripts were detected in the C. glutamicum Δpgi and C. glutamicum Δpgi(pEKEx3) strains, both of which lack Pgi activity. Expression of ptsG was similar in WT C. glutamicum and C. glutamicum Δpgi(pEKEx3-pgi). Taken together, these results show that in C. glutamicum strains lacking glycolysis, glucose uptake as well as ptsG expression was drastically reduced. To test if the reduced ptsG expression is indeed responsible for the observed poor growth phenotype of Pgi-deficient C. glutamicum strains during cultivation on glucose, plasmid pBB1-ptsG was introduced into the pgi deletion mutant. This plasmid pBB1-ptsG has previously been shown to lead to constitutive expression of high levels of ptsG (50). C. glutamicum Δpgi carrying this plasmid showed improved growth on glucose (growth rate μ = 0.28 ± 0.02 h−1) (Fig. 1C) and improved glucose uptake (17.1 ± 3.8 nmol min−1 mg cdm−1) (Fig. 2A). With C. glutamicum Δpgi(pBB1), which carries the empty pBB1 plasmid, neither growth on glucose nor uptake of glucose was affected (growth rate μ = 0.03 ± 0.01 h−1; glucose uptake rate, 5.1 ± 1.2 nmol min−1 mg cdm−1). Taken together, these results show that besides the already-described NADPH-dependent inhibition of the enzymes for the oxidative part of the PPP (11), transcription of ptsG was severely reduced in C. glutamicum Δpgi, which caused the strongly reduced glucose uptake in this strain.

Residual glucose uptake in C. glutamicum Δpgi is PTS mediated.

Although almost no ptsG transcripts were detected in C. glutamicum Δpgi cells cultivated on glucose (Fig. 2B), this strain was still able to take up glucose (Fig. 2A) and could be cultivated with glucose as the sole carbon source (Fig. 1A), although uptake as well as growth proceeded slowly (glucose uptake rate, 8.6 ± 0.6 nmol min−1 mg cdm−1; growth rate, 0.05 ± 0.03 h−1). Growth of C. glutamicum Δpgi proceeded very similarly to the growth on glucose described for the Hpr-deficient strain C. glutamicum Δhpr as well as the EIIABCGlc-deficient ptsG insertion mutant C. glutamicum IMptsG (growth rates of 0.03 ± 0.00 h−1 and 0.06 ± 0.02 h−1, respectively, were reported [41]). Based on this observation, it might be concluded that glucose uptake and phosphorylation in C. glutamicum Δpgi are brought about PTS independently by either one or both of the two inositol permeases (IolT1 and IolT2) and one or both of the two glucose kinases Glk and PpgK (41, 42). However, in the present work [14C]glucose uptake rates were measured at a substrate concentration of 100 μM, which is at least 250 times lower than the substrate constant determined for both IolT1- and IolT2-mediated glucose uptake (KS values of above 25 mM were recently determined [41]). As a matter of fact, at a glucose concentration of 100 μM, no uptake of 14C-labeled glucose was measured for PTS-deficient C. glutamicum strains such as C. glutamicum Δhpr (41). Taken together, these results indicate that the residual [14C]glucose uptake in C. glutamicum Δpgi is mediated by the PTS. To confirm the EIIABCGlc-dependent glucose utilization in C. glutamicum Δpgi, the ptsG inactivation mutant C. glutamicum Δpgi IMptsG was constructed by insertional mutagenesis. Both growth on glucose and uptake of 14C-labeled glucose were completely abolished in C. glutamicum Δpgi IMptsG. Therefore, we conclude that despite the low transcription of ptsG in C. glutamicum Δpgi, slow PTS-mediated glucose uptake still takes place and is essential for growth of this strain on glucose.

Optimization of l-lysine production in pgi-negative C. glutamicum strains.

The pgi gene was deleted in the l-lysine-producing strain C. glutamicum DM1729 (pycP458S, homV59A, lysCT311I), resulting in the strain C. glutamicum DM1729 Δpgi. As expected, l-lysine production as well as yield was increased and biomass formation decreased in C. glutamicum DM1729 Δpgi(pEKEX3) compared to the parental strain C. glutamicum DM1729(pEKEX3) (Table 3); however, productivity was significantly lowered in the strain carrying the pgi deletion. The l-lysine production rate decreased from 1.03 mM h−1 with C. glutamicum DM1729(pEKEX3) to 0.60 mM h−1 with C. glutamicum DM1729 Δpgi(pEKEX3) (Table 3). Introduction of the E. coli transhydrogenase UdhA, encoded on plasmid pEKEX3-udhA, caused a drastic decrease of l-lysine production. In detail, l-lysine production was reduced by expression of udhA from 58 ± 8 mM with C. glutamicum DM1729 Δpgi(pEKEX3) to 26 ± 1 mM with C. glutamicum DM1729 Δpgi(pEKEX3-udhA), which corresponds to the amount of lysine produced by the parental strain C. glutamicum DM1729(pEKEX3) (27 ± 1 mM) (Table 3). Thus, the transhydrogenase UdhA is not suitable for improvement of l-lysine production, as it neutralized the advantage of pgi deletion for the l-lysine titer. Taken together, these results show that optimized NADPH provision is required for efficient l-lysine production in C. glutamicum and can be accomplished by inactivation of glycolysis. However, this strategy for strain improvement comes along with drastic negative effects on both productivity and growth.

Table 3.

l-Lysine production and biomass formation from 4% glucosea

| Strain | l-Lysine (mM) | Biomass (g cdm liter−1) | Incubation time (h)b | Production rate (mM h−1) | Yield |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mol mol−1 | g g−1 | |||||

| DM1729(pEKEx3) | 27 ± 1 | 14.3 ± 0.5 | 26 | 1.03 | 0.120 ± 0.003 | 0.097 ± 0.003 |

| DM1729 Δpgi(pEKEx3) | 58 ± 8 | 9.8 ± 1.2 | 96 | 0.60 | 0.260 ± 0.037 | 0.211 ± 0.030 |

| DM1729(pEKEx3-udhA) | 19 ± 2 | 11.5 ± 1.0 | 26 | 0.75 | 0.088 ± 0.008 | 0.071 ± 0.006 |

| DM1729 Δpgi(pEKEx3-udhA) | 26 ± 1 | 9.1 ± 0.6 | 48 | 0.55 | 0.119 ± 0.004 | 0.097 ± 0.004 |

| DM1729(pBB1) | 25 ± 1 | 12.2 ± 0.7 | 24 | 1.03 | 0.111 ± 0.005 | 0.090 ± 0.004 |

| DM1729 Δpgi(pBB1) | 39 ± 2 | 10.7 ± 0.7 | 96 | 0.40 | 0.174 ± 0.007 | 0.141 ± 0.006 |

| DM1729(pBB1-ptsG) | 24 ± 1 | 13.1 ± 0.6 | 24 | 1.02 | 0.110 ± 0.004 | 0.089 ± 0.003 |

| DM1729 Δpgi(pBB1-ptsG) | 48 ± 2 | 11.1 ± 0.4 | 54 | 0.88 | 0.215 ± 0.010 | 0.174 ± 0.008 |

Data are means and standard deviations and represent results from at least three independent experiments.

Incubation time corresponds to the period of time the cultures needed to fully consume the initially provided glucose.

Overexpression of ptsG was also tested for the pgi-deficient l-lysine production strain C. glutamicum DM1729 Δpgi. As shown in Table 2, overexpression of ptsG in C. glutamicum DM1729 Δpgi indeed improved the strain's performance toward fast and efficient l-lysine production; the l-lysine production rate increased from 0.40 mM h−1 in C. glutamicum DM1729 Δpgi(pBB1) to 0.88 mM h−1 in C. glutamicum DM1729 Δpgi(pBB1-ptsG). Furthermore, ptsG overexpression in the pgi-deficient l-lysine production strain also increased the l-lysine yield from 0.174 ± 0.007 mol mol−1 to 0.215 ± 0.010 mol mol−1 in C. glutamicum DM1729 Δpgi(pBB1) and C. glutamicum DM1729 Δpgi(pBB1-ptsG), respectively. Thus, the l-lysine yield in C. glutamicum DM1729 Δpgi(pBB1-ptsG) was doubled and the production rate was reduced by only about 15% compared to those in C. glutamicum DM1729(pBB1). Overexpression of ptsG in the parental strain C. glutamicum DM1729 did not significantly alter l-lysine production, productivity, yield, or biomass formation (Table 3). Taken together, these results show that by combination of both pgi deletion and ptsG overexpression C. glutamicum strains were improved toward efficient as well as fast l-lysine production.

DISCUSSION

The decrease of product yields in C. glutamicum l-lysine production strains carrying the E. coli transhydrogenase UdhA shows the direct connection between NADPH supply and l-lysine synthesis. Improved NADPH provision is indeed responsible for the increased l-lysine production in C. glutamicum strains when the carbon flux is redirected toward the PPP by deletion of pgi. However, this strategy of strain improvement came along with severe negative effects on productivity as well as biomass formation, which are not caused by increased intracellular NADPH concentrations but by the negative effect on glucose uptake described here. The reduced glucose uptake is caused by the downregulation of ptsG transcription in Pgi-deficient C. glutamicum strains in the presence of glucose. Negative effects of glucose on glucose uptake and ptsG transcript levels were also reported for Pgi-deficient E. coli strains (34). These responses to counteract so-called phosphosugar stress in E. coli are accomplished by the complex regulatory network comprising small RNA-initiated inhibition of ptsG translation (38), inhibition of glucose uptake by a polypeptide (35), and Hfq-dependent ptsG mRNA degradation by RNase E (39). Phosphosugar stress has hitherto not been investigated in C. glutamicum. It is unlikely that the mechanisms for the response against accumulation of sugar phosphates are identical in E. coli and C. glutamicum, as the latter organism does not possess an Hfq homologue (55). Expression of ptsG in C. glutamicum is well known to be controlled by the global DeoR-type repressor SugR (56). However, the regulon of SugR also comprises, apart from ptsG, genes for glycolysis (pfkA, fba, eno, and pyk, encoding 6-phosphofructokinase, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase, enolase, and pyruvate kinase, respectively) and for all PTS components, namely, ptsI, ptsH, ptsF, and ptsS (encoding the general components EI and Hpr, the fructose-specific EII, and the sucrose-specific EII, respectively) (57–59). The negative effects on growth on and uptake of glucose in C. glutamicum Δpgi were here shown to be relieved upon overexpression of ptsG. From these results, it can be concluded that apart from ptsG, no other PTS gene is repressed in C. glutamicum Δpgi. Therefore, it is unlikely that the repressor of all PTS genes, SugR, is responsible for the effects on ptsG expression in C. glutamicum Δpgi described here. C. glutamicum possesses two redundant GntR-type like regulators, GntR1 and GntR2 (60), both of which activate ptsG transcription in the absence of the alternative carbon source gluconate. Furthermore, GntR1 and GntR2 repress the genes encoding gluconate permease (gntP), gluconate kinase (gntK), and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (gnd) and to some extent the pentose phosphate pathway gene cluster tkt-tal-zwf-opcA-devB (60). Reduced expression of ptsG in the pgi deletion mutant might originate from missing transcriptional activation when GntR1 and GntR2 are released from the ptsG promoter region. In general, release of GntR1 and GntR2 from the promoter regions of the PPP genes and thus increased amounts of PPP enzymes should be favorable for growth of C. glutamicum Δpgi. However, only gluconate and glucono-d-lactone and not the PPP intermediate 6-phosphogluconate interfere with binding of GntR1 and GntR2 to their target promoters (60). Gluconate and glucono-d-lactone are not formed in the course of glucose utilization in C. glutamicum (40). Thus, the proposed release of GntR1 and GntR2 from the ptsG promoter region, which might lead to the observed reduced ptsG expression, remains hypothetical.

Directing the glycolytic flux toward the PPP to increase the NADPH supply is a common strategy in rational C. glutamicum strain design (3, 10, 19, 26). The lack of ptsG transcription in Pgi-deficient C. glutamicum strains described here, which is responsible for the poor utilization of glucose by these strains, is a novel target for strain improvement. Therefore, it might be worthwhile to study the underlying mechanism for glucose uptake inhibition in this organism in more detail.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ute Meyer and Eva Glees for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 February 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Wendisch VF. (ed). 2007. Amino acid biosynthesis—pathways, regulation and metabolic engineering. Springer Verlag, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blombach B, Schreiner ME, Holatko J, Bartek T, Oldiges M, Eikmanns BJ. 2007. l-Valine production with pyruvate dehydrogenase complex-deficient Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:2079–2084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blombach B, Schreiner ME, Bartek T, Oldiges M, Eikmanns BJ. 2008. Corynebacterium glutamicum tailored for high-yield l-valine production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 79:471–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marx A, Striegel K, de Graaf AA, Sahm H, Eggeling L. 1997. Response of the central metabolism of Corynebacterium glutamicum to different flux burdens. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 56:168–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sonntag K, Eggeling L, De Graaf AA, Sahm H. 1993. Flux partitioning in the split pathway of lysine synthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Quantification by 13C- and 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Eur. J. Biochem. 213:1325–1331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schrumpf B, Schwarzer A, Kalinowski J, Puhler A, Eggeling L, Sahm H. 1991. A functionally split pathway for lysine synthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 173:4510–4516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Marienhagen J, Kennerknecht N, Sahm H, Eggeling L. 2005. Functional analysis of all aminotransferase proteins inferred from the genome sequence of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 187:7639–7646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leyval D, Uy D, Delaunay S, Goergen JL, Engasser JM. 2003. Characterisation of the enzyme activities involved in the valine biosynthetic pathway in a valine-producing strain of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Biotechnol. 104:241–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wittmann C, Becker J. 2007. The l-lysine story: from metabolic pathways to industrial production, p 39–70 In Wendisch VF. (ed), Amino acid biosynthesis—pathways, regulation and metabolic engineering. Springer Verlag, Berlin, Germany [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bartek T, Blombach B, Zonnchen E, Makus P, Lang S, Eikmanns BJ, Oldiges M. 2010. Importance of NADPH supply for improved l-valine formation in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biotechnol. Prog. 26:361–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moritz B, Striegel K, De Graaf AA, Sahm H. 2000. Kinetic properties of the glucose-6-phosphate and 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenases from Corynebacterium glutamicum and their application for predicting pentose phosphate pathway flux in vivo. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:3442–3452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ihnen ED, Demain AL. 1969. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and its deficiency in mutants of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 98:1151–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ohnishi J, Katahira R, Mitsuhashi S, Kakita S, Ikeda M. 2005. A novel gnd mutation leading to increased l-lysine production in Corynebacterium glutamicum. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 242:265–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eikmanns BJ, Rittmann D, Sahm H. 1995. Cloning, sequence analysis, expression, and inactivation of the Corynebacterium glutamicum icd gene encoding isocitrate dehydrogenase and biochemical characterization of the enzyme. J. Bacteriol. 177:774–782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen R, Yang H. 2000. A highly specific monomeric isocitrate dehydrogenase from Corynebacterium glutamicum. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 383:238–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Georgi T, Rittmann D, Wendisch VF. 2005. Lysine and glutamate production by Corynebacterium glutamicum on glucose, fructose and sucrose: roles of malic enzyme and fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. Metab. Eng. 7:291–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gourdon P, Baucher MF, Lindley ND, Guyonvarch A. 2000. Cloning of the malic enzyme gene from Corynebacterium glutamicum and role of the enzyme in lactate metabolism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:2981–2987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dominguez H, Rollin C, Guyonvarch A, Guerquin-Kern JL, Cocaign-Bousquet M, Lindley ND. 1998. Carbon-flux distribution in the central metabolic pathways of Corynebacterium glutamicum during growth on fructose. Eur. J. Biochem. 254:96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Blombach B, Riester T, Wieschalka S, Ziert C, Youn JW, Wendisch VF, Eikmanns BJ. 2011. Corynebacterium glutamicum tailored for efficient isobutanol production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:3300–3310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wittmann C, Heinzle E. 2002. Genealogy profiling through strain improvement by using metabolic network analysis: metabolic flux genealogy of several generations of lysine-producing corynebacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5843–5859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kiefer P, Heinzle E, Zelder O, Wittmann C. 2004. Comparative metabolic flux analysis of lysine-producing Corynebacterium glutamicum cultured on glucose or fructose. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:229–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Marx A, de Graaf AA, Wiechert W, Eggeling L, Sahm H. 1996. Determination of the fluxes in the central metabolism of Corynebacterium glutamicum by nuclear magnetic resonance spetroscopy combined with metabolite balancing. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 49:111–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marx A, Eikmanns BJ, Sahm H, de Graaf AA, Eggeling L. 1999. Response of the central metabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum to the use of an NADH-dependent glutamate dehydrogenase. Metab. Eng. 1:35–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Becker J, Klopprogge C, Herold A, Zelder O, Bolten CJ, Wittmann C. 2007. Metabolic flux engineering of l-lysine production in Corynebacterium glutamicum—overexpression and modification of G6P dehydro+genase. J. Biotechnol. 132:99–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Becker J, Klopprogge C, Zelder O, Heinzle E, Wittmann C. 2005. Amplified expression of fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase in Corynebacterium glutamicum increases in vivo flux through the pentose phosphate pathway and lysine production on different carbon sources. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:8587–8596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Marx A, Hans S, Mockel B, Bathe B, de Graaf AA. 2003. Metabolic phenotype of phosphoglucose isomerase mutants of Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Biotechnol. 104:185–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fraenkel DG, Levisohn SR. 1967. Glucose and gluconate metabolism in an Escherichia coli mutant lacking phosphoglucose isomerase. J. Bacteriol. 93:1571–1578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vinopal RT, Hillman JD, Schulman H, Reznikoff WS, Fraenkel DG. 1975. New phosphoglucose isomerase mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 122:1172–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hua Q, Yang C, Baba T, Mori H, Shimizu K. 2003. Responses of the central metabolism in Escherichia coli to phosphoglucose isomerase and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase knockouts. J. Bacteriol. 185:7053–7067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sauer U, Canonaco F, Heri S, Perrenoud A, Fischer E. 2004. The soluble and membrane-bound transhydrogenases UdhA and PntAB have divergent functions in NADPH metabolism of Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 279:6613–6619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Boonstra B, French CE, Wainwright I, Bruce NC. 1999. The udhA gene of Escherichia coli encodes a soluble pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase. J. Bacteriol. 181:1030–1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Canonaco F, Hess TA, Heri S, Wang T, Szyperski T, Sauer U. 2001. Metabolic flux response to phosphoglucose isomerase knock-out in Escherichia coli and impact of overexpression of the soluble transhydrogenase UdhA. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 204:247–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Charusanti P, Conrad TM, Knight EM, Venkataraman K, Fong NL, Xie B, Gao Y, Palsson BO. 2010. Genetic basis of growth adaptation of Escherichia coli after deletion of pgi, a major metabolic gene. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001186 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kimata K, Tanaka Y, Inada T, Aiba H. 2001. Expression of the glucose transporter gene, ptsG, is regulated at the mRNA degradation step in response to glycolytic flux in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 20:3587–3595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wadler CS, Vanderpool CK. 2007. A dual function for a bacterial small RNA: SgrS performs base pairing-dependent regulation and encodes a functional polypeptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:20454–20459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Postma PW, Lengeler JW, Jacobson GR. 1993. Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase systems of bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 57:543–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Vanderpool CK, Gottesman S. 2004. Involvement of a novel transcriptional activator and small RNA in post-transcriptional regulation of the glucose phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system. Mol. Microbiol. 54:1076–1089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maki K, Uno K, Morita T, Aiba H. 2008. RNA, but not protein partners, is directly responsible for translational silencing by a bacterial Hfq-binding small RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:10332–10337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morita T, Maki K, Aiba H. 2005. RNase E-based ribonucleoprotein complexes: mechanical basis of mRNA destabilization mediated by bacterial noncoding RNAs. Genes Dev. 19:2176–2186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Blombach B, Seibold GM. 2010. Carbohydrate metabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum and applications for the metabolic engineering of l-lysine production strains. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 86:1313–1322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lindner SN, Seibold GM, Henrich A, Kramer R, Wendisch VF. 2011. Phosphotransferase system-independent glucose utilization in Corynebacterium glutamicum by inositol permeases and glucokinases. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:3571–3581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lindner SN, Seibold GM, Kramer R, Wendisch VF. 2011. Impact of a new glucose utilization pathway in amino acid-producing Corynebacterium glutamicum. Bioeng. Bugs 2:291–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sambrook J, Russell D. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratoy Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 44. Keilhauer C, Eggeling L, Sahm H. 1993. Isoleucine synthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum: molecular analysis of the ilvB-ilvN-ilvC operon. J. Bacteriol. 175:5595–5603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Seibold G, Dempf S, Schreiner J, Eikmanns BJ. 2007. Glycogen formation in Corynebacterium glutamicum and role of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Microbiology 153:1275–1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Seibold GM, Wurst M, Eikmanns BJ. 2009. Roles of maltodextrin and glycogen phosphorylases in maltose utilization and glycogen metabolism in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Microbiology 155:347–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Eikmanns BJ, Thum-Schmitz N, Eggeling L, Ludtke KU, Sahm H. 1994. Nucleotide sequence, expression and transcriptional analysis of the Corynebacterium glutamicum gltA gene encoding citrate synthase. Microbiology 140:1817–1828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Tauch A, Kirchner O, Löffler B, Gotker S, Pühler A, Kalinowski J. 2002. Efficient electrotransformation of Corynebacterium diphtheriae with a mini-replicon derived from the Corynebacterium glutamicum plasmid pGA1. Curr. Microbiol. 45:362–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stansen C, Uy D, Delaunay S, Eggeling L, Goergen JL, Wendisch VF. 2005. Characterization of a Corynebacterium glutamicum lactate utilization operon induced during temperature-triggered glutamate production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:5920–5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Krause FS, Henrich A, Blombach B, Kramer R, Eikmanns BJ, Seibold GM. 2010. Increased glucose utilization in Corynebacterium glutamicum by use of maltose, and its application for the improvement of l-valine productivity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:370–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Reinscheid DJ, Schnicke S, Rittmann D, Zahnow U, Sahm H, Eikmanns BJ. 1999. Cloning, sequence analysis, expression and inactivation of the Corynebacterium glutamicum pta-ack operon encoding phosphotransacetylase and acetate kinase. Microbiology 145:503–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Park SM, Sinskey AJ, Stephanopoulos G. 1997. Metabolic and physiological studies of Corynebacterium glutamicum mutants. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 55:864–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Möker N, Brocker M, Schaffer S, Krämer R, Morbach S, Bott M. 2004. Deletion of the genes encoding the MtrA-MtrB two-component system of Corynebacterium glutamicum has a strong influence on cell morphology, antibiotics susceptibility and expression of genes involved in osmoprotection. Mol. Microbiol. 54:420–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kabus A, Georgi T, Wendisch VF, Bott M. 2007. Expression of the Escherichia coli pntAB genes encoding a membrane-bound transhydrogenase in Corynebacterium glutamicum improves l-lysine formation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Kalinowski J, Bathe B, Bartels D, Bischoff N, Bott M, Burkovski A, Dusch N, Eggeling L, Eikmanns BJ, Gaigalat L, Goesmann A, Hartmann M, Huthmacher K, Krämer R, Linke B, McHardy AC, Meyer F, Möckel B, Pfefferle W, Pühler A, Rey DA, Rückert C, Rupp O, Sahm H, Wendisch VF, Wiegrabe I, Tauch A. 2003. The complete Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 genome sequence and its impact on the production of l-aspartate-derived amino acids and vitamins. J. Biotechnol. 104:5–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Engels V, Wendisch VF. 2007. The DeoR-type regulator SugR represses expression of ptsG in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 189:2955–2966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tanaka Y, Teramoto H, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2008. Regulation of expression of general components of the phosphoenolpyruvate: carbohydrate phosphotransferase system (PTS) by the global regulator SugR in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 78:309–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gaigalat L, Schluter JP, Hartmann M, Mormann S, Tauch A, Pühler A, Kalinowski J. 2007. The DeoR-type transcriptional regulator SugR acts as a repressor for genes encoding the phosphoenolpyruvate:sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) in Corynebacterium glutamicum. BMC Mol. Biol. 8:104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Engels V, Lindner SN, Wendisch VF. 2008. The global repressor SugR controls expression of genes of glycolysis and of the l-lactate dehydrogenase LdhA in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J. Bacteriol. 190:8033–8044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Frunzke J, Engels V, Hasenbein S, Gatgens C, Bott M. 2008. Co-ordinated regulation of gluconate catabolism and glucose uptake in Corynebacterium glutamicum by two functionally equivalent transcriptional regulators, GntR1 and GntR2. Mol. Microbiol. 67:305–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Hanahan D. 1983. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 166:557–580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Blattner FR, Plunkett G, III, Bloch CA, Perna NT, Burland V, Riley M, Collado-Vides J, Glasner JD, Rode CK, Mayhew GF, Gregor J, Davis NW, Kirkpatrick HA, Goeden MA, Rose DJ, Mau B, Shao Y. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science 277:1453–1474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Schäfer A, Tauch A, Jäger Kalinowski WJ, Thierbach G, Pühler A. 1994. Small mobilizable multi-purpose cloning vectors derived from the Escherichia coli plasmids pK18 and pK19: selection of defined deletions in the chromosome of Corynebacterium glutamicum. Gene 145:69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]