Abstract

A comprehensive gene disruption of lacticin Q biosynthetic cluster lnqQBCDEF was carried out. The results demonstrated the necessity of the complete set of lnqQBCDEF for lacticin Q production, whereas immunity was flexible, with LnqEF (ABC transporter) being essential for and LnqBCD partially contributing to immunity.

TEXT

Bacteriocins are a diverse group of antimicrobial peptides that are ribosomally synthesized and extracellularly released by their producers. The genes necessary for bacteriocin production and immunity are located near the structural gene and are generally arranged as an operon (1, 2). Lacticin Q (LnqQ), produced by Lactococcus lactis QU 5 (3), is an unmodified leaderless bacteriocin that has a unique gene cluster (lnqBCDEF) following the structural gene (lnqQ) (4). As predicted in silico, lnqEF encodes an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter with LnqE as the membrane-spanning domain and LnqF as the cytoplasmic ATPase domain. These two open reading frames (ORFs) share some sequence similarities with ORF3 and Abc2 in the bht-b locus of Streptococcus rattus BHT (5) whose bacteriocin, BHT-B, shows some homology to LnqQ (47% identity). LnqBCD has no sequence similarity to any other bacteriocin biosynthetic proteins. However, according to a BLAST search, LnqB (79 amino acids [aa]) shows partial homology to the ABC transporter permease (407 aa) of Listeria welshimeri (36% identity) or the Na+/H+ antiporter (1,143 aa) of Puccinellia tenuiflora (30% identity), whereas LnqC (159 aa) shows homology to the membrane permease (181 aa) of Renibacterium salmoninarum (27% identity) or the membrane-flanked domain protein (165 aa) of Xylanimonas cellulosilytica (25% identity). LnqD, the largest ORF (432 aa) in the lnqQ locus, has some homology to the membrane protein (486 aa) of Lactobacillus buchneri (25% identity) and the YdbT homolog protein (484 aa) of Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides (23% identity). Previous work has revealed that a set of lnqBCDEF confers the secretion and self-immunity of LnqQ; however, the role of each gene product has not been elucidated (4). Thus, in this study, comprehensive gene disruption was carried out to determine the necessity of each gene and to deduce its role in LnqQ biosynthesis.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Culture conditions for the strains listed, DNA manipulation, and other molecular cloning techniques were as described previously (4, 7–9). An inverse PCR technique (11) was used to create an in-frame deletion of the gene(s) of interest from the template plasmid, pLNQ, which contains lnqQBCDEF under the control of lactococcal promoter P32 (4). In one case, primers invF1 and invR1 (Table 2) were used to amplify the entire plasmid (pLNQ) without the lnqB region. The PCR products were then phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) and self-ligated with Ligation-High (Toyobo), resulting in the generation of a plasmid with lnqB disrupted (pLNQΔB). Similarly, plasmids with each gene or several genes disrupted were generated by using the primers listed in Table 2 and were introduced into Escherichia coli DH5α for plasmid replication. After the sequence was confirmed, each recombinant plasmid was introduced into L. lactis subsp. cremoris NZ9000 (L. lactis NZ9000) by the electroporation method (12). The LnqQ production (secretion) and self-immunity levels of recombinants were evaluated by the spot-on-lawn method (13). The activity titer, described in arbitrary units (AU) per milliliter, was defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution causing a growth inhibition zone on the indicator lawn. The MIC in this study was defined as the lowest concentration of purified bacteriocin that produced a measurable inhibition zone on the indicator lawn.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| L. lactis NZ9000 | Plasmid-free derivative of L. lactis subsp. cremoris MG1363, pepN::nisRK | 6 |

| Bacillus coagulans JCM 2257T | Bacteriocin indicator | JCMb |

| Escherichia coli DH5α | supE44 ΔlacU169 (ϕ80lacZΔM15) hsdR17 recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 relA1 | TaKaRa |

| L. lactis QU 5 | Lacticin Q producer | Lab collection (3) |

| L. lactis QU 14 | Lacticin Z producer | Lab collection (7) |

| L. lactis QU 4 | Lactococcin Q producer | Lab collection (8) |

| Lactococcus sp. strain QU 12 | Lactocyclicin Q producer | Lab collection (9) |

| L. lactis NCDO 497 | Nisin A producer | NCDOc |

| Enterococcus faecium T13 | Enterocin L50 producer | Lab collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMG36c | pWV01-based expression vector carrying the strong lactococcal promoter P32; Cmra | 10 |

| pMGlnqQ | pMG36c derivative with lnqQ under the control of P32; Cmr | 4 |

| pLNQ | pMGlnqQ derivative with lnqBCDEF downstream of lnqQ; Cmr | 4 |

| pLNQΔQ | pLNQ derivative lacking lnqQ; Cmr | 4 |

| pLNQΔQF | pLNQ derivative lacking lnqQ, lnqF; Cmr | This study |

| pLNQΔB | pLNQ derivative lacking lnqB; Cmr | This study |

| pLNQΔC | pLNQ derivative lacking lnqC; Cmr | This study |

| pLNQΔD | pLNQ derivative lacking lnqD; Cmr | This study |

| pLNQΔE | pLNQ derivative lacking lnqE; Cmr | This study |

| pLNQΔF | pLNQ derivative lacking lnqF; Cmr | This study |

| pLNQΔBC | pLNQ derivative lacking lnqBC; Cmr | This study |

| pLNQΔBCD | pLNQ derivative lacking lnqBCD; Cmr | This study |

| pLNQΔBCDE | pLNQ derivative lacking lnqBCDE; Cmr | This study |

Cmr, chloramphenicol resistance.

JCM, Japan Collection of Microorganism, Saitama, Japan.

NCDO, National Collection of Dairy Organisms, Reading, United Kingdom.

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Nucleotide sequence | Application |

|---|---|---|

| invF1 | 5′-GCATTGGTAGGGAGAGCG-3′ | pLNQΔB |

| invR1 | 5′-CATCTAGATGATCAAAAAATTACTTAATACC-3′ | pLNQΔB/pLNQΔBC/pLNQΔBCD/pLNQΔBCDE |

| invF2 | 5′-GAGTTAATGATAAATGCTTTGGAAAGTC-3′ | pLNQΔC/pLNQΔBC |

| invR2 | 5′-CGATTTGAAACCTTGAAATATAAACTACT-3′ | pLNQΔC |

| invF3 | 5′-GTATTCAGGTGTTTAGAAATGAGG-3′ | pLNQΔD/pLNQΔBCD |

| invR3 | 5′-GATAGATCTCATTTATTAAAGTTAGTCTCG-3′ | pLNQΔD/ |

| invF4 | 5′-CAATCTAGTTCTAAAAAATGTCAATATGG-3′ | pLNQΔE/pLNQΔBCDE |

| invR4 | 5′-CTTGCATTATTTCCTCATTTCTAAACACC-3′ | pLNQΔE |

| invF5 | 5′-AAGAGCAAAGAAAGTTGAAAGATGTG-3′ | pLNQΔF/pLNQΔQF |

| invR5 | 5′-CCATATTGACATTTTTTAGAACTAGATTG-3′ | pLNQΔF/pLNQΔQF |

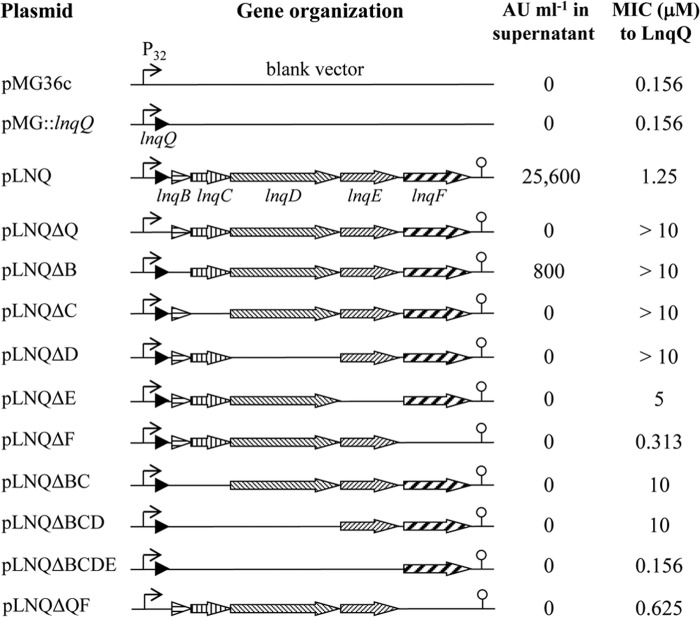

An overview of the LnqQ secretion/immunity levels of recombinants is shown in Fig. 1. With regard to LnqQ secretion, antimicrobial activity in the culture supernatant of L. lactis NZ9000(pLNQ) against Bacillus coagulans JCM 2257T, which is a highly LnqQ-sensitive indicator strain, was estimated at 25,600 AU ml−1. This activity was, however, totally lost when the lnqC, lnqD, lnqE, or lnqF gene was disrupted, whereas slight activity (800 AU ml−1) was detected in an lnqB-deficient recombinant. Meanwhile, antimicrobial activity was detected in the cell extracts of all of the recombinants (data not shown), indicating that LnqQ was expressed but not extracellularly released by these recombinants. On the one hand, disruption of a single gene did not have a severe impact on LnqQ immunity, except for the disruption of lnqF, which led to a drastic loss of immunity. Even in the absence of lnqB, lnqC, or lnqD, the recombinants showed >64-fold higher immunity levels than the control strain, L. lactis NZ9000(pMG36c), while the lack of lnqE slightly reduced the immunity level. Considering the abundant immunity achieved by lnqBC- or lnqBCD-deficient recombinants, LnqEF is clearly the main contributor to LnqQ immunity. In many other cases, an ABC-type transporter mediates bacteriocin immunity by extruding the peptide and thus preventing direct access to the target molecule (14–17). Although LnqE is supposedly an ABC transporter constituent, considerable immunity was observed in an lnqE-deficient recombinant, L. lactis NZ9000(pLNQΔE). This observation suggests the possibility that another factor(s) can complement the role of LnqE; furthermore, this complementation should be accomplished by any of the LnqBCD proteins but not by host-derived proteins when considering the deficient immunity observed in an lnqBCDE-deficient recombinant. In addition, all of those membrane proteins (LnqBCDE) provided the host cells with partial immunity, even when the ABC transporter was inactive (pLNQΔF/pLNQΔQF), which was, however, far inferior to full immunity.

Fig 1.

Overview of the lacticin Q production and immunity of L. lactis NZ9000 recombinants. Gene organizations corresponding to the recombinant plasmids are schematically depicted. Arrows with patterns indicate cloned genes, bent arrows represent lactococcal promoter P32, and lollipops represent the putative terminator region found downstream of lnqF. LnqQ secretion and immunity levels were evaluated as described in the text and are represented as AU of activity against B. coagulans JCM 2257T per milliliter or MICs of purified LnqQ, respectively.

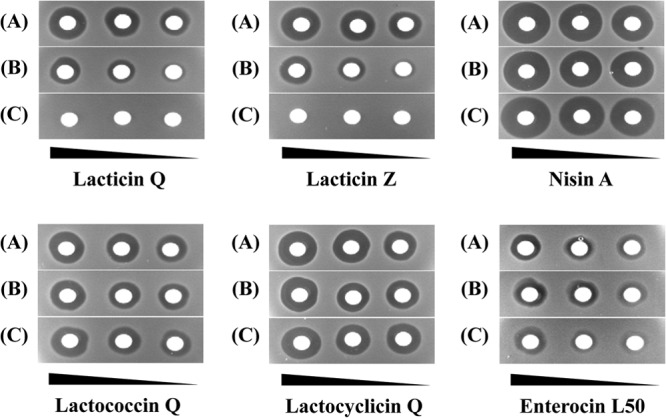

The other leaderless bacteriocins genetically characterized to date have only one ABC-type transporter encoded in their gene loci (5, 18–23). This may indicate that leaderless bacteriocins have in common the feature of having one dedicated ABC transporter mediate both secretion and immunity. LmrB, an ABC-type multidrug efflux pump, facilitates the secretion and the immunity of a leaderless bacteriocin, LsbB (20). A remarkable aspect of LmrB is its broad substrate specificity, by which it works for another bacteriocin, LsbA, from the same producer. Interestingly, LmrB shows high degrees of similarity to other leaderless bacteriocin transporters, EntQB (19) and AurT (22), despite the absence of observed sequence similarity between the structures of these bacteriocins. This fact gave rise to a simple question regarding the substrate specificity of LnqQ immunity. In this regard, several types of bacteriocins, i.e., nisin A (class I), lactococcin Q (class IIb), lactocyclicin Q (class IIc), enterocin L50 (class IId, leaderless), and lacticin Z (class IId, LnqQ homologue), were used to evaluate the specificity of LnqQ immunity. Both full immunity (lnqBCDEF) and partial immunity (lnqBCDE) to only lacticin Z and not to the other types of bacteriocins were seen (Fig. 2).

Fig 2.

Lacticin Q/Z-specific immunity facilitated by LnqBCDEF. Twofold serially diluted bacteriocin-containing culture supernatants were spotted onto a lawn containing the strains tested, i.e., L. lactis NZ9000(pMG36c) (A), NZ9000(pLNQΔQF) (B), and NZ9000(pLNQΔQ) (C).

In summary, the secretion of LnqQ is strictly controlled by the presence of LnqBCDEF, whereas immunity is flexible in that LnqEF (ABC transporter) is the minimal unit required for sufficient immunity. Here, LnqBCD could be considered accessory proteins that support the activity of LnqEF, although such proteins potentially associated with other bacteriocin transporters are usually single gene products (24–27). A distinct feature of leaderless bacteriocins is their synthesis without a leader peptide. Because this N-terminal extension in the bacteriocin prepeptide acts as a recognition signal for its dedicated transporter (2), there should be a unique bacteriocin transfer or recognition system in leaderless bacteriocin producers. The present results might indicate the involvement of LnqBCD in this unknown mechanism. The detailed function of LnqBCD, dependent on or independent of LnqEF, is now under investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was partially supported by a Grand-in-Aid for Scientific Research and JSPS fellows from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 18 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Drider D, Fimland G, Héchard Y, McMullen LM, Prévost H. 2006. The continuing story of class IIa bacteriocins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70:564–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nes IF, Diep DB, Havarstein LS, Brurberg MB, Eijsink V, Holo H. 1996. Biosynthesis of bacteriocins in lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 70:113–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujita K, Ichimasa S, Zendo T, Koga S, Yoneyama F, Nakayama J, Sonomoto K. 2007. Structural analysis and characterization of lacticin Q, a novel bacteriocin belonging to a new family of unmodified bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:2871–2877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwatani S, Yoneyama F, Miyashita S, Zendo T, Nakayama J, Sonomoto K. 2012. Identification of the genes involved in the secretion and self immunity of lacticin Q, an unmodified leaderless bacteriocin from Lactococcus lactis QU 5. Microbiology 158:2927–2935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyink O, Balakrishnan M, Tagg JR. 2005. Streptococcus rattus strain BHT produces both a class I two-component lantibiotic and a class II bacteriocin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 252:235–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuipers OP, de Ruyter PGGA, Kleerebezem M, de Vos WM. 1998. Quorum sensing-controlled gene expression in lactic acid bacteria. J. Biotechnol. 64:15–21 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iwatani S, Zendo T, Yoneyama F, Nakayama J, Sonomoto K. 2007. Characterization and structure analysis of a novel bacteriocin, lacticin Z, produced by Lactococcus lactis QU 14. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 71:1984–1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zendo T, Koga S, Shigeri Y, Nakayama J, Sonomoto K. 2006. Lactococcin Q, a novel two-peptide bacteriocin produced by Lactococcus lactis QU 4. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:3383–3389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawa N, Zendo T, Kiyofuji J, Fujita K, Himeno K, Nakayama J, Sonomoto K. 2009. Identification and characterization of lactocyclicin Q, a novel cyclic bacteriocin produced by Lactococcus sp. strain QU 12. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:1552–1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van de Guchte M, van der Vossen JM, Kok J, Venema G. 1989. Construction of a lactococcal expression vector: expression of hen egg white lysozyme in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:224–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ochman H, Gerber AS, Hartl DL. 1988. Genetic applications of an inverse polymerase chain reaction. Genetics 120:621–623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holo H, Nes IF. 1995. Transformation of Lactococcus by electroporation. Methods Mol. Biol. 47:195–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ennahar S, Asou Y, Zendo T, Sonomoto K, Ishizaki A. 2001. Biochemical and genetic evidence for production of enterocins A and B by Enterococcus faecium WHE 81. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 70:291–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins B, Curtis N, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. 2010. The ABC transporter AnrAB contributes to the innate resistance of Listeria monocytogenes to nisin, bacitracin, and various β-lactam antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4416–4423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz M, Valdivia E, Martinez-Bueno M, Fernandez M, Soler-Gonzalez AS, Ramirez-Rodrigo H, Maqueda M. 2003. Characterization of a new operon, as-48EFGH, from the as-48 gene cluster involved in immunity to enterocin AS-48. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1229–1236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Margolles A, Florez AB, Moreno JA, van Sinderen D, de los Reyes-Gavilan CG. 2006. Two membrane proteins from Bifidobacterium breve UCC2003 constitute an ABC-type multidrug transporter. Microbiology 152:3497–3505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein T, Heinzmann S, Solovieva I, Entian KD. 2003. Function of Lactococcus lactis nisin immunity genes nisI and nisFEG after coordinated expression in the surrogate host Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 278:89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cintas LM, Casaus P, Holo H, Hernandez PE, Nes IF, Havarstein LS. 1998. Enterocins L50A and L50B, two novel bacteriocins from Enterococcus faecium L50, are related to staphylococcal hemolysins. J. Bacteriol. 180:1988–1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Criado R, Diep DB, Aakra A, Gutierrez J, Nes IF, Hernandez PE, Cintas LM. 2006. Complete sequence of the enterocin Q-encoding plasmid pCIZ2 from the multiple bacteriocin producer Enterococcus faecium L50 and genetic characterization of enterocin Q. production and immunity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:6653–6666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gajic O, Buist G, Kojic M, Topisirovic L, Kuipers OP, Kok J. 2003. Novel mechanism of bacteriocin secretion and immunity carried out by lactococcal multidrug resistance proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 278:34291–34298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nascimento Jdos S, Coelho ML, Ceotto H, Potter A, Fleming LR, Salehian Z, Nes IF, Bastos Mdo C. 2012. Genes involved in immunity to and secretion of aureocin A53, an atypical class II bacteriocin produced by Staphylococcus aureus A53. J. Bacteriol. 194:875–883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Netz DJ, Sahl HG, Marcelino R, dos Santos Nascimento J, de Oliveira SS, Soares MB, Bastos Mdo C. 2001. Molecular characterisation of aureocin A70, a multi-peptide bacteriocin isolated from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Mol. Biol. 311:939–949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandiford S, Upton M. 2012. Identification, characterization, and recombinant expression of epidermicin NI01, a novel unmodified bacteriocin produced by Staphylococcus epidermidis that displays potent activity against staphylococci. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:1539–1547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Birri DJ, Brede DA, Forberg T, Holo H, Nes IF. 2010. Molecular and genetic characterization of a novel bacteriocin locus in Enterococcus avium isolates from infants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:483–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hille M, Kies S, Gotz F, Peschel A. 2001. Dual role of GdmH in producer immunity and secretion of the staphylococcal lantibiotics gallidermin and epidermin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1380–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lagos R, Baeza M, Corsini G, Hetz C, Strahsburger E, Castillo JA, Vergara C, Monasterio O. 2001. Structure, organization and characterization of the gene cluster involved in the production of microcin E492, a channel-forming bacteriocin. Mol. Microbiol. 42:229–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Keeffe T, Hill C, Ross RP. 1999. Characterization and heterologous expression of the genes encoding enterocin A production, immunity, and regulation in Enterococcus faecium DPC1146. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:1506–1515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]