Abstract

ATP modulates immune cell functions, and ATP derived from gut commensal bacteria promotes the differentiation of T helper 17 (Th17) cells in the intestinal lamina propria. We recently reported that Enterococcus gallinarum, isolated from mice and humans, secretes ATP. We have since found and characterized several ATP-secreting bacteria. Of the tested enterococci, Enterococcus mundtii secreted the greatest amount of ATP (>2 μM/108 cells) after overnight culture. Glucose, not amino acids and vitamins, was essential for ATP secretion from E. mundtii. Analyses of energy-deprived cells demonstrated that glycolysis is the most important pathway for bacterial ATP secretion. Furthermore, exponential-phase E. mundtii and Enterococcus faecalis cells secrete ATP more efficiently than stationary-phase cells. Other bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus, also secrete ATP in exponential but not stationary phase. These results suggest that various gut bacteria, including commensals and pathogens, might secrete ATP at any growth phase and modulate immune cell function.

INTRODUCTION

ATP is the source of energy within living cells and acts as an allosteric effector of numerous cell processes, such as active transport, nucleic acid synthesis, muscle activity, and movement (1–5).

In mammalian cells, ATP is the neurotransmitter for purinergic signal transmission (6). ATP is stored in secretory vesicles and exocytosed, leading to various purinergic responses, such as central control of autonomic functions, pain and mechanosensory transduction, neural-glial interactions, control of vessel tone and angiogenesis, and platelet aggregation through purinoceptors, thus establishing its role as a chemical transmitter (7–11).

ATP modulates immune cell function by activating the ATP receptors P2X and P2Y (11–13). Furthermore, ATP has been found in the intestinal lumen, where it promotes differentiation of T helper 17 (Th17) cells in the lamina propria (14). Germ-free (GF) mice exhibited much lower concentrations of fecal ATP, accompanied by fewer lamina propria Th17 cells, than specific-pathogen-free (SPF) mice. In addition, antibiotic-treated SPF mice showed marked reductions in the number of Th17 cells and in the concentration of fecal ATP. Systemic or rectal administration of ATP markedly increases the number of lamina propria Th17 cells in GF mice. Thus, ATP driven from commensal bacteria activates the lamina propria, leading to local differentiation of Th17 cells. However, ATP-secreting bacteria have not been identified in the intestinal lumen of SPF mice.

Recently, we reported that Enterococcus gallinarum, a vancomycin-resistant Gram-positive coccus isolated from SPF mice, secretes ATP; other tested bacteria, such as Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium, Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus, did not (15). To our knowledge, this is the first report of the isolation and identification of ATP-secreting bacteria from the feces of SPF mice. However, whether other enterococcal species secrete ATP and what culture conditions are optimal for ATP secretion remain unclear.

In this study, we found that several enterococcal strains other than E. gallinarum secrete ATP; Enterococcus mundtii secretes the greatest amount of ATP. We therefore used this strain to discover that glucose is an essential nutrient and that glycolysis is important for ATP secretion under the tested conditions. Furthermore, biochemical analyses using energy-deprived cells revealed that exponential-phase cells secreted more efficiently than stationary-phase cells. We also showed that several other bacterial species secrete ATP at exponential phase even though ATP secretion was not detected after overnight (O/N) culture.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Bacterial strains used in this study are described in Table 1. All strains were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI; BD, NJ) medium at 37°C O/N and then stored at −80°C in 20% (wt/vol) glycerol. RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, CA), nutrient broth (NB; BD, NJ), Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (LB; Merck, Germany), tryptic soy broth (TSB; BD, NJ), heart infusion (HI) broth (HI; BD, NJ), and BHI medium were used in this study.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Species | Straina | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Enterococcus asini | NBRC 100681T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus avium | NBRC 100477T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus camelliae | NBRC 101868T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus canis | NBRC 100695T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus cecorum | NBRC 100674T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus dispar | NBRC 100678T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus durans | NBRC 100479T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus faecalis | CG110 | 34 |

| Enterococcus faecium | NBRC 100485T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus gallinarum | Egm10 | 15 |

| Enterococcus gilvus | NBRC 100696T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus hirae | NBRC 3181T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus malodoratus | NBRC 100489T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus moraviensis | NBRC 100710T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus mundtii | NBRC 100490T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus pallens | NBRC 100697T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus phoeniculicola | NBRC 100711T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus pseudoavium | NBRC 100491T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus raffinosus | NBRC 100492T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus saccharolyticus | NBRC 100493T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus sulfureus | NBRC 100680T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus thailandicus | NBRC 101867T | NBRC |

| Enterococcus villorum | NBRC 100699T | NBRC |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Ishii | This study |

| Escherichia coli | MC4100 | 35 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | JCM2874 | JCM |

The superscript “T” indicates the type strain of the species. NBRC, National Institute of Technology and Evaluation Biological Resource Center, Japan; JCM, Japan Collection of Microorganisms.

Preparation of culture supernatant.

All strains were precultured in 5 ml of BHI medium for 16 h at 37°C under aerobic conditions with shaking. After cells reached stationary phase, the cultures were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 10 min, and the cell pellets were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium. The cell suspensions were then inoculated into RPMI 1640 medium to an optical density at 660 nm (OD660) of 0.1 and cultured for 16 h at 37°C under aerobic conditions with shaking. Growth was monitored by measuring the OD660 with a Taitec MiniPhoto 518R spectrophotometer. To investigate the effect of oxygen on ATP secretion, E. mundtii NBRC 100490T was cultured anaerobically in an anaerobic jar (Mitsubishi Gas Chemical Company, Inc., Japan) at 37°C for 16 h with shaking. If required, NB, LB broth, TSB, HI broth, BHI medium, and modified RPMI 1640 medium (with no amino acids, vitamins, or glucose; pH 7.4) were used instead of RPMI 1640 medium. To determine the effect of glucose on bacterial ATP secretion, 0.2% (wt/vol) or 1% (wt/vol) glucose was added to NB, LB, TSB, HI, and BHI media. Cultures were centrifuged at 4,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were filtered using a 0.2-μm-pore-size membrane (Kanto Chemical Co., Inc., Japan) to completely remove residual cells. The filtered culture supernatants were used for quantification of extracellular ATP.

Quantification of extracellular and intracellular ATP.

The filtered culture supernatant (100 μl) was mixed with an equal volume of BacTiter-Glo ATP measurement reagent (Promega, Inc., WI). The bioluminescence response in relative light units was detected (500 ms) with a luminometer (Luminoskan Ascent; Thermo Fisher Scientific KK, Japan). ATP concentration was determined using standard ATP (Sigma, MO) solutions. RPMI 1640 medium was used as the negative control. To measure the concentration of intracellular ATP, bacterial cultures were directly mixed with BacTiter-Glo ATP measurement reagent. The cell lysis time for these bacteria was empirically determined to be 5 min. The concentration of intracellular ATP was calculated by subtracting the amount of extracellular ATP from that of the uncentrifuged bacterial cultures. Bioluminescence measurements for each sample were obtained in triplicate. Reconstituted BacTiter-Glo reagent has a minimum half-life of over 30 min; reagent decay did not limit the detection of ATP in these experiments.

Preparation of energy-deprived cells and inhibition of glycolysis.

At mid-exponential (OD660 of 0.6) and stationary phases (cultivation for 16 h), E. mundtii NBRC 100490T and E. faecalis CG110 cells grown in BHI medium were harvested and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C. To deprive the cells of intracellular ATP, the suspensions were incubated for 30 min in 0.5 mM dinitrophenol at 37°C and washed three times with ice-cold PBS (17). After samples were subjected to centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the cell pellets were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium without glucose, and the suspensions were incubated at 37°C for 2 h in the presence or absence of 1% (wt/vol) glucose. Glycolysis inhibition was performed by adding 10 μM iodoacetic acid (IAA) to the energy-deprived cells of E. mundtii 100490T at 60 min after the addition of glucose. At specific time points (see Fig. 4), intracellular and extracellular ATP concentrations were measured as described above.

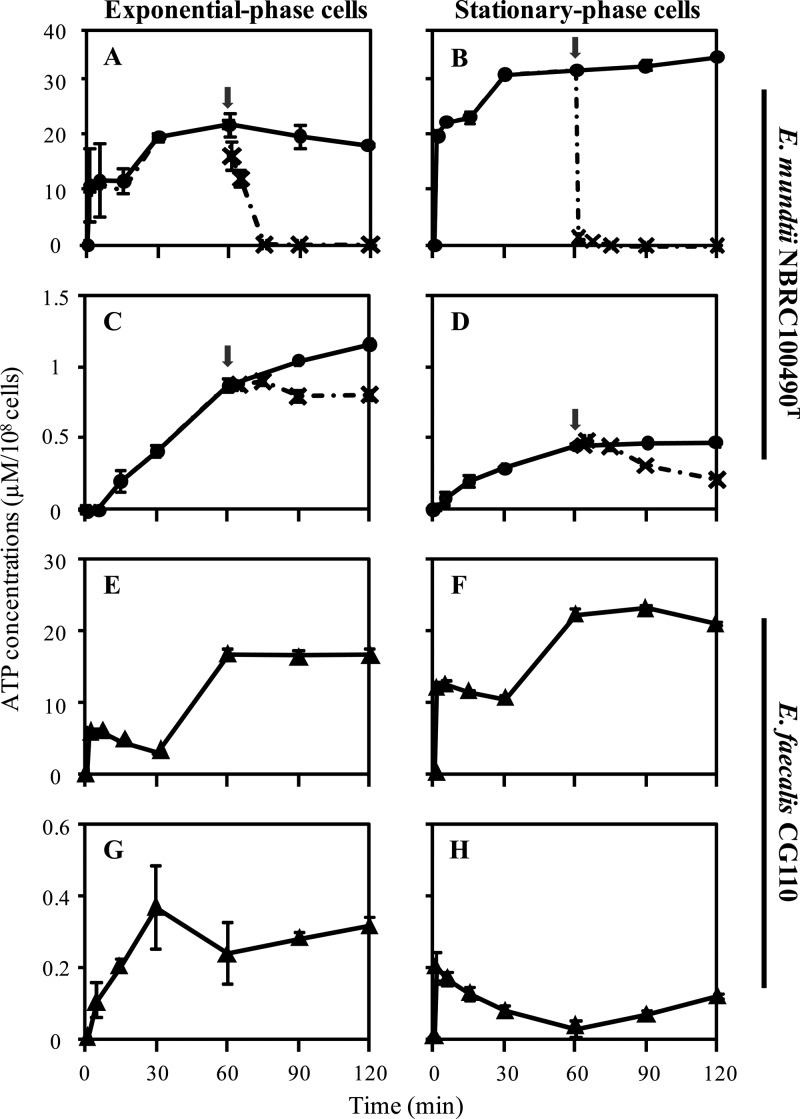

Fig 4.

Time-dependent change of intracellular and extracellular ATP concentrations in energy-deprived enterococcal cells. Energy-deprived E. mundtii NBRC 100490T (●) and E. faecalis CG110 (▲) cells at mid-exponential phase (OD660 of 0.6) (A, C, E, and G) and stationary phase (cultivation for 16 h at 37°C) (B, D, F, and H) were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Intracellular (A, B, E, and F) and extracellular (C, D, G, and H) ATP was measured in the presence of 1% (wt/vol) glucose. The arrows represent the time of addition of IAA. ×, ATP concentrations in the presence of IAA. Data are the means of triplicate experiments, and error bars indicate standard deviations.

Bacterial viability assay.

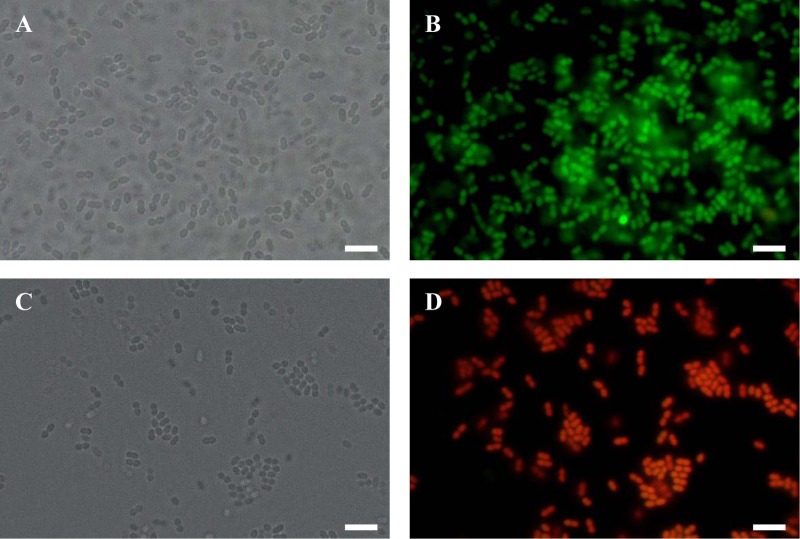

Exponential-phase energy-deprived cells of E. mundtii NBRC 100490T were stained with a Live/Dead BacLight bacterial viability kit (Invitrogen, CA) and observed by fluorescence microscopy (Eclipse E600; Nikon, Japan). Isopropyl alcohol-treated cells were used as a control for dead cells.

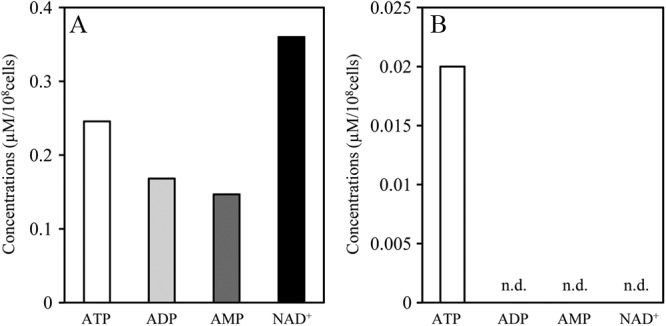

Quantification of metabolites.

Exponential-phase energy-deprived cells of E. mundtii NBRC 100490T were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium without glucose that was supplemented with 1% (wt/vol) glucose and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. After incubation, intracellular and extracellular concentrations of ATP, ADP, AMP, and NAD+ were measured by capillary electrophoresis time of flight mass spectrometry (CE-TOFMS) in Human Metabolome Technologies, Inc., Japan.

Statistical analysis.

The data were analyzed with a two-tailed Student's t test (Microsoft Excel 2007). A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

ATP secretion by enterococcal species.

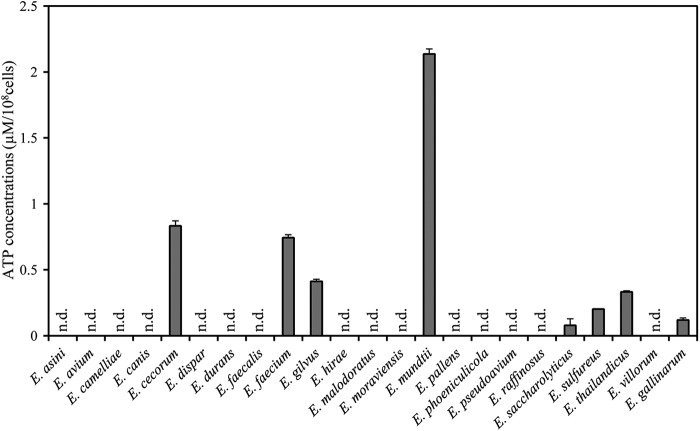

We recently reported that E. gallinarum, a commensal enterococcal species in mice and humans, secretes ATP, but other tested bacteria did not (15). In this study, we further examined the ATP-secreting property of 22 enterococcal species available from the National Institute of Technology and Evaluation Biological Resource Center Japan (NBRC) or gifted from J. Nakayama (Kyushu University, Japan) (Table 1). As shown in Fig. 1, we identified seven new ATP-secreting enterococcal strains: Enterococcus cecorum NBRC 100674T, E. faecium NBRC 100485T, Enterococcus gilvus NBRC 100696T, E. mundtii NBRC 100490T, Enterococcus saccharolyticus NBRC 100493T, Enterococcus sulfureus NBRC 100680T, and Enterococcus thailandicus NBRC 101867T. E. mundtii NBRC 100490T secreted the greatest amount of ATP (>2 μM/108 cells), much more than that produced by a previously isolated E. gallinarum (<1 μM/108 cells). This strain was used for the remainder of our analyses.

Fig 1.

ATP-secreting property of enterococcal strains. The indicated enterococcal strains were precultured to stationary phase, harvested, and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium. The cell suspensions were subsequently inoculated into RPMI 1640 medium to an OD660 of 0.1 and cultured for 16 h at 37°C under aerobic conditions with shaking. Extracellular ATP was measured as described in Materials and Methods. Data are the means of triplicate experiments, and the error bars indicate standard deviations. n.d., not detected.

Effect of culture medium on ATP secretion by E. mundtii.

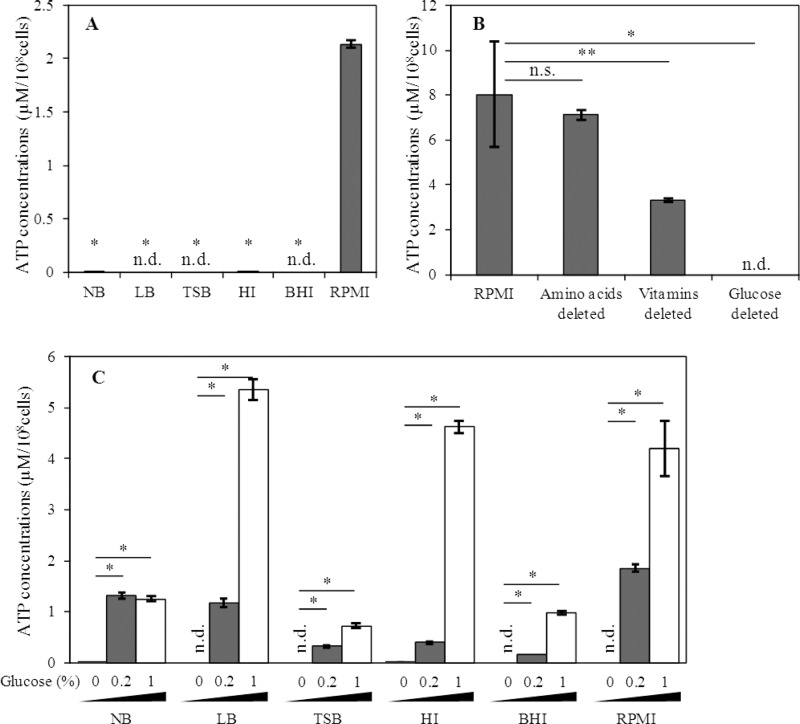

In our previous study, only RPMI 1640 medium was used to analyze bacterial ATP secretion (15). To assess the physiological significance of culture conditions for ATP secretion, we used various media, such as NB, LB broth, TSB, HI medium, and BHI medium, which are generally used for bacterial cultivation, in addition to RPMI 1640 medium. After incubation of E. mundtii NBRC 100490T at 37°C for 16 h, concentrations of extracellular ATP were measured. Notably, extracellular ATP was found only when the bacterium was cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Fig. 2A), suggesting that the element or elements that exist in RPMI 1640 medium but do not exist in the other media are necessary for bacterial ATP secretion. Since RPMI 1640 medium is a complete synthetic medium, all compositions have been defined, and certain nutrients can easily be eliminated on demand. To determine the most important factor for ATP secretion by E. mundtii NBRC 100490T, we used modified RPMI 1640 medium in which all components of commercial RPMI 1640 medium were mixed manually, and amino acids, vitamins, or glucose were omitted as needed. The bacterial growth was impaired in all deletion groups; therefore ATP concentrations were expressed per 108 cells. Remarkably, the bacterium did not secrete ATP in the absence of glucose (Fig. 2B). Deletion of amino acids and vitamins yielded negligible and moderate effects, respectively. These results strongly suggest that glucose in RPMI 1640 medium is critical for secretion of ATP. The glucose concentration in RPMI 1640 medium is 0.2% (wt/vol) and is below the level of detection in the other tested media.

Fig 2.

Effect of culture medium on ATP secretion of E. mundtii. (A) E. mundtii NBRC 100490T was cultured under aerobic conditions with shaking for 16 h at 37°C in the indicated media. (B) E. mundtii NBRC 100490T was cultured under aerobic conditions with shaking for 16 h at 37°C in modified RPMI 1640 medium in which amino acids, vitamins, or glucose was omitted from the RPMI 1640 medium. (C) E. mundtii NBRC 100490T was cultured under aerobic conditions with shaking for 16 h at 37°C in the indicated media supplemented with 0.2% (wt/vol) and 1% (wt/vol) glucose. Extracellular ATP was measured as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Data are the means of triplicate experiments, and error bars indicate standard deviations. n.d., not detected; n.s., not significant; ⁎, P < 0.01; ⁎⁎, P < 0.05.

To investigate the effect of glucose on ATP secretion by E. mundtii NBRC 100490T more precisely, glucose was added to the indicated culture medium, and the amount of extracellular ATP secreted by the bacterium was measured. Although effective glucose concentrations varied by medium, E. mundtii NBRC 100490T secreted ATP in all tested culture media supplemented with 0.2% (wt/vol) (basal level in RPMI 1640 medium) and 1% (wt/vol) glucose (Fig. 2C). These results clearly indicate that glucose promotes bacterial ATP secretion.

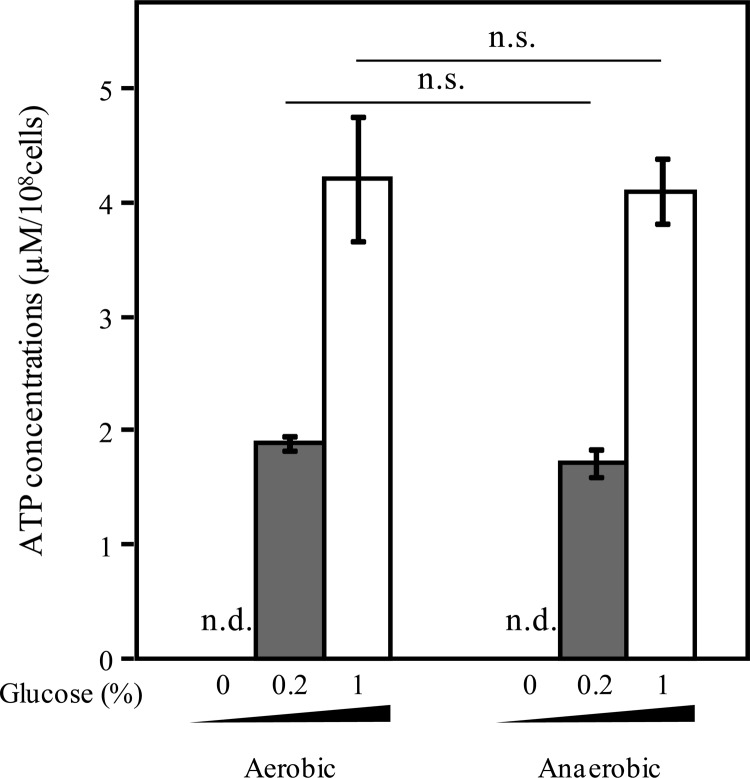

Effect of oxygen on bacterial ATP secretion.

Oxygen is one of the major factors influencing bacterial growth and ATP synthesis. To examine oxygen requirements for ATP secretion, E. mundtii NBRC 100490T was cultured under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. As shown in Fig. 3, no significant difference in the amounts of extracellular ATP secreted by this strain was observed under these conditions. In addition, culture ODs under anaerobic conditions were similar to those of cultures grown under aerobic conditions. These results indicate that oxygen is dispensable for ATP secretion and growth of this strain. Although ATP is generally synthesized by glycolysis, the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) cycle, and electron transfer system, no lactic acid bacteria (LAB) have been reported to carry genes required for a complete TCA cycle (18). Furthermore, LAB are nonrespiring, fermenting, acid-producing bacteria that cannot perform respiratory metabolism except under specific conditions (19). This knowledge and our results suggest that glycolysis is crucial for ATP secretion.

Fig 3.

Oxygen requirement for bacterial ATP secretion. E. mundtii NBRC 100490T was cultured under aerobic or anaerobic conditions with shaking for 16 h at 37°C in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 0.2% (wt/vol) or 1% (wt/vol) glucose. Extracellular ATP was measured as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Data are the means of triplicate experiments, and error bars indicate standard deviations. n.d., not detected; n.s., not significant.

Glucose-dependent ATP secretion by energy-deprived cells.

The use of growing cells is sometimes not effective for analyzing metabolic pathways and biochemical reactions in vitro. In these cases, resting cells and in vitro reconstituted model systems are useful. In this study, we used energy-deprived cells prepared by treatment with dinitrophenol, which disrupts membrane potential and inhibits ATP synthesis driven by F1Fo ATPase (20). After cells are incubated with dinitrophenol for several minutes, intracellular ATP is completely exhausted and converted to ADP, AMP, and adenosine (20).

By adding glucose to energy-deprived E. mundtii NBRC 100490T and E. faecalis CG110 cells, time-dependent changes in intracellular and extracellular ATP were determined. After the addition of glucose to energy-deprived E. mundtii NBRC 100490T cells prepared at mid-exponential phase, a two-step elevation of intracellular ATP was observed. The first increase occurred immediately and was maintained from 5 min to 15 min; a second increase occurred, and then the amount of ATP decreased gradually after reaching the maximum level (Fig. 4A). In contrast, extracellular ATP increased gradually from 5 min to the end of the experiment (120 min) (Fig. 4C).

When IAA, a glycolysis inhibitor, was added to the energy-deprived cells at 60 min, intracellular ATP decreased immediately, and extracellular ATP became constant (Fig. 4A and C). These results indicate that ATP synthesis was completely arrested by IAA inhibition of glycolysis and suggest that ATP produced by glycolysis from glucose might be secreted into the extracellular milieu. We also used energy-deprived cells prepared at stationary phase and investigated intracellular and extracellular ATP levels. Elevation of intracellular ATP in stationary-phase cells was observed immediately after the addition of glucose, and, subsequently, the level was higher than that in exponential-phase cells (Fig. 4B); however, stationary-phase cells secreted less ATP than exponential-phase cells (Fig. 4D). Addition of IAA to energy-deprived cells prepared at stationary phase showed that intracellular ATP decreased more rapidly than it did in exponential-phase cells (Fig. 4B), and extracellular ATP decreased gradually (Fig. 4D). Intracellular and extracellular ATP did not increase without glucose supplementation in exponential- and stationary-phase cells (data not shown), indicating again that glucose is essential for ATP synthesis and secretion.

E. faecalis CG110, an ATP-secretion-negative strain, was used in the first trial using O/N cultures (Fig. 1); intracellular ATP exhibited a two-step increase (Fig. 4E and F), and exponential-phase cells secreted much more ATP than stationary-phase cells, as is the case in E. mundtii NBRC 100490T (Fig. 4G and H).

In these experiments, we determined bacterial CFU counts at 0 h and 2 h after the addition of glucose and found that the bacterial CFU counts remained constant (data not shown). We also analyzed the viability of exponential-phase energy-deprived E. mundtii NBRC 100490T cells by Live/Dead staining and observed very few dead cells (Fig. 5). These results suggest that cell integrity was maintained and that extracellular ATP is not due to bacteriolysis. In addition, to confirm whether there exist any metabolites other than ATP, such as ADP, AMP, and NAD+, CE-TOFMS was performed (Fig. 6). No other metabolites were detected in the extracellular milieu although intracellular concentrations of ADP and AMP were approximately two-thirds the ATP concentration, and NAD+ was approximately 1.5 times the ATP concentration. These results might eliminate the possibility that extracellular ATP production was simply due to bacteriolysis.

Fig 5.

Fluorescence microscopy images of energy-deprived E. mundtii NBRC 100490T cells stained for cell viability. Exponential-phase energy-deprived cells of E. mundtii NBRC 100490T were untreated (A and B) or treated with 70% isopropyl alcohol (C and D). Bacterial cells were stained with a Live/Dead BacLight bacterial viability kit. Live cells and dead cells are stained in green and red, respectively. Scale bar, 5 μm.

Fig 6.

Metabolite concentrations of E. mundtii NBRC 100490T. Exponential-phase energy-deprived cells of E. mundtii NBRC 100490T were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 1% (wt/vol) glucose and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. After incubation, intracellular (A) and extracellular (B) concentrations of the indicated metabolites were measured by CE-TOFMS. n.d., not detected (<0.01 μM).

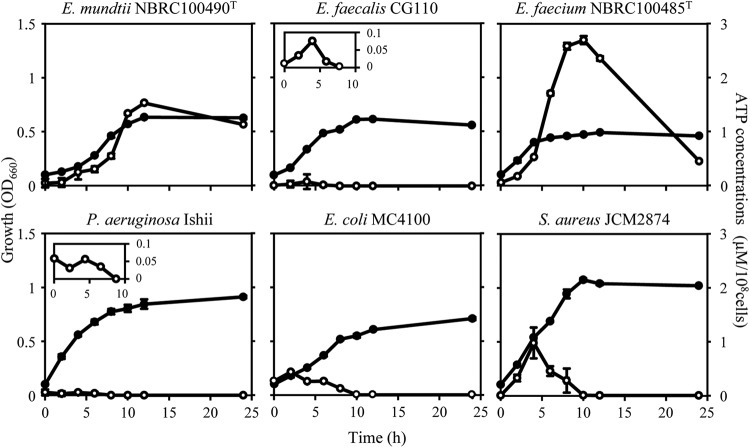

Bacteria generally secrete ATP during growth.

Bacterial ATP secretion has been examined using O/N culture supernatants, but we showed that exponential-phase cells secrete much more ATP than stationary-phase cells by using energy-deprived cells, as described above. We assumed that enterococcal species and bacteria belonging to other genera might secrete ATP during growth. Here, we monitored bacterial growth and extracellular ATP concentrations of E. mundtii NBRC 100490T, E. faecalis CG110, E. faecium NBRC 100485T, Pseudomonas aeruginosa Ishii, E. coli MC4100, and S. aureus JCM2874 (Fig. 7). As expected, E. mundtii NBRC 100490T cells secrete large amounts of ATP, from exponential phase to early stationary phase. From late exponential phase to early stationary phase, surprisingly, E. faecium NBRC 100485T secreted much more ATP than did E. mundtii NBRC 100490T although at late stationary phase, the extracellular ATP concentration in E. mundtii NBRC 100490T was higher. In the case of E. faecalis CG110, a low but significant amount of extracellular ATP was detected at exponential phase although it was not detected in O/N cultures. P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and S. aureus also secreted ATP only at exponential phase. In addition, we measured extracellular ATP in each bacterial strain cultured in RPMI 1640 medium without glucose and detected no extracellular ATP at all tested time points (Table 2). These results suggest that a variety of bacteria have the potential to secrete ATP in a growth-phase-dependent manner in the presence of glucose.

Fig 7.

Extracellular ATP concentrations during bacterial growth. Growth (●) of and extracellular ATP concentrations (○) in E. mundtii NBRC 100490T, E. faecalis CG110, E. faecium NBRC 100485T, P. aeruginosa Ishii, E. coli MC4100, and S. aureus JCM2874 are shown. Data are the means of triplicate experiments, and error bars indicate standard deviations. (Insets) Enlarged view of the period 0 to 10 h.

Table 2.

Extracellular ATP concentrations in bacterial culture supernatants at various time points

| Organism | ATP concn (μM/108 cells) by treatment and time point (h)a |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + Glucose |

− Glucose |

|||||

| 0 | 4 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 8 | |

| E. mundtii | 0.05 ± 0.079 | 0.25 ± 0.135 | 0.55 ± 0.046 | ND | ND | ND |

| E. faecalis | 0.01 ± 0.018 | 0.079 ± 0.137 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| E. faecium | 0.051 ± 0.015 | 0.524 ± 0.007 | 2.576 ± 0.065 | ND | ND | ND |

| P. aeruginosa | 0.053 ± 0.055 | 0.051 ± 0.027 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| E. coli | 0.255 ± 0.013 | 0.249 ± 0.003 | 0.119 ± 0.007 | ND | ND | ND |

| S. aureus | ND | 0.970 ± 0.285 | 0.273 ± 0.222 | ND | ND | ND |

Cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium with (+) or without (−) glucose supplementation. The data are presented as the means ± standard deviations of three experiments. ND, not detected.

DISCUSSION

ATP derived from commensal bacteria drives differentiation of intestinal Th17 cells, and administration of ATP exacerbates a T-cell-mediated colitis model with enhanced Th17 cells (14). Thus, clarifying bacterial ATP secretion mechanisms will provide important insight into the cause of chronic ulcerative colitis. We reported that E. gallinarum, isolated from SPF mice, secretes ATP (15). In this study, we found seven new enterococcal species that secrete ATP (e.g., E. mundtii secretes a large amount of ATP) (Fig. 1). E. mundtii is a Gram-positive coccus, lactic acid bacterium isolated from cow teats, the hands of milkers, plants, and soil (21). The species has rarely been isolated from human sources, and there is little evidence of virulence in humans (22, 23). However, the other ATP-secreting enterococcus, E. faecium, is important for nosocomial infections (24, 25). E. gilvus was isolated from the bile of a patient suffering from cholecystitis (pathogenic role is unclear) (26), and E. cecorum is associated with endocarditis (27). Therefore, ATP-secreting enterococci might be considered clinically problematic pathogens.

Furthermore, we found that glucose is an essential nutrient for bacterial ATP secretion (Fig. 2). Luminal glucose concentration in the gut depends on the time of day and the segment of the gut; concentrations in the small intestine ranged from 0.2 to 48 mM in rats fed regular chow (28). Thus, our tested glucose concentrations (0, 0.2, and 1% [wt/vol]) were consistent with normal physiological conditions in the gut. These findings might suggest that luminal glucose is sufficient for ATP secretion by gut microbes. In addition, E. mundtii NBRC 100490T secreted ATP under aerobic and anaerobic conditions in the presence of glucose (Fig. 3), and inhibition of glycolysis suppressed ATP secretion (Fig. 4). These findings indicate that glycolysis is crucial for bacterial ATP secretion.

Kinetic analyses of ATP secretion in energy-deprived enterococci demonstrated that intracellular ATP immediately increased after the addition of glucose, and subsequently extracellular ATP increased (Fig. 4). Furthermore, exponential-phase cells secrete more efficiently than stationary-phase cells (Fig. 4). There are two explanations for this phenomenon. First, the stringent response is associated with the reduction of ATP secretion in stationary phase. During the stringent response, cells attenuate rRNA synthesis, induce and repress metabolic pathways in accordance with their physiological needs, and induce many stationary-phase survival genes (29). Thus, stationary-phase cells may use ATP to maintain cellular functions and prepare for regrowth, so they secrete less ATP than exponential-phase cells. Second, some ATP export machinery may be expressed less at stationary than at exponential phase.

In addition, we confirmed cell integrity and checked metabolite leakage of exponential-phase energy-deprived E. mundtii 100490T cells (Fig. 5 and 6). These results indicate that extracellular ATP is not simply due to bacteriolysis and that bacteria secrete ATP spontaneously.

Our finding that exponential-phase cells secrete much higher concentrations of ATP motivated us to reexamine whether bacteria other than enterococci secrete ATP during growth. Interestingly, all tested bacteria, including P. aeruginosa, E. coli, and S. aureus that are regarded as commensal bacteria or infectious microbes, secreted ATP at exponential phase even though extracellular ATP was not detected in O/N culture supernatants (Fig. 7). Therefore, various bacterial species may secrete ATP at any growth stage. Although ATP secretion varied, nanomolar amounts of ATP near the mammalian cell surface are sufficient to elicit functional changes such as neutrophil chemotaxis and airway epithelial cell volume regulation (16, 30–32). Accordingly, all bacteria tested in this study may have the ability to modulate mammalian cellular functions. Our results support the hypothesis that commensal bacterium-derived ATP activates specific dendritic cells in the lamina propria to induce inflammatory cytokines, leading to local differentiation of Th17 cells, thereby exacerbating colitis (14).

Several mechanisms, such as ATP binding cassette transporters, connexin hemichannels, stretch-activated channels, cargo-vesicle trafficking, and exocytotic granule secretion (4, 33), are probably involved in ATP secretion from bacteria. Our results have potentially important implications for clarifying the roles and the mechanisms of bacterial ATP secretion. The entire mechanism of bacterial ATP-secreting systems is an interesting topic for future studies, which will provide further information about ATP-mediated bacteria-bacteria communication and bacteria-host interactions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants-in-aid for scientific research (C) 23590521 from the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sports of Japan and The Jikei University Graduate Research Fund.

We thank Jiro Nakayama for the gift of E. faecalis CG110 and Satomi Yamada for technical support.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 January 2013

REFERENCES

- 1. Brown GC. 1992. Control of respiration and ATP synthesis in mammalian mitochondria and cells. Biochem. J. 284:1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Burnstock G, Campbell G, Satchell D, Smythe A. 1970. Evidence that adenosine triphosphate or a related nucleotide is the transmitter substance released by non-adrenergic inhibitory nerves in the gut. Br. J. Pharmacol. 40:668–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jouaville LS, Pinton P, Bastianutto C, Rutter GA, Rizzuto R. 1999. Regulation of mitochondrial ATP synthesis by calcium: evidence for a long-term metabolic priming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:13807–13812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lundin A, Thore A. 1975. Comparison of methods for extract of bacterial adenine nucleotides determined by firefly assay. Appl. Microbiol. 30:713–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perriman R, Barta I, Voeltz GK, Abelson J, Ares M., Jr 2003. ATP requirement for Prp5p function is determined by Cus2p and the structure of U2 small nuclear RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100:13857–13862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burnstock G. 2006. Historical review: ATP as a neurotransmitter. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 27:166–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burnstock G. 2007. Physiology and pathophysiology of purinergic neurotransmission. Physiol. Rev. 87:659–797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Johnson RG., Jr 1988. Accumulation of biological amines into chromaffin granules: a model for hormone and neurotransmitter transport. Physiol. Rev. 68:232–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pankratov Y, Lalo U, Verkhratsky A, North RA. 2006. Vesicular release of ATP at central synapses. Pflugers Arch. 452:589–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sawada K, Echigo N, Juge N, Miyaji T, Otsuka M, Omote H, Yamamoto A, Moriyama Y. 2008. Identification of a vesicular nucleotide transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:5683–5686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schnurr M, Toy T, Shin A, Waqner M, Cebon J, Maraskovsky E. 2005. Extracellular nucleotide signaling by P2 receptors inhibits IL-12 and enhances IL-23 expression in human dendritic cells: a novel role for the cAMP pathway. Blood 105:1582–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khakh BS, North RA. 2006. P2X receptors as cell-surface ATP sensors in health and disease. Nature 442:527–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. North RA. 2002. Molecular physiology of P2X receptors. Physiol. Rev. 82:1013–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Atarashi K, Nishimura J, Shima T, Umesaki Y, Yamamoto M, Onoue M, Yagita H, Ishii N, Evans R, Honda K, Takeda K. 2008. ATP drives lamina propria Th17 cell differentiation. Nature 455:808–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Iwase T, Shinji H, Tajima A, Sato F, Tamura T, Iwamoto T, Yoneda M, Mizunoe Y. 2010. Isolation and identification of ATP-secreting bacteria from mice and humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1949–1951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Okada SF, Nicholas RA, Kreda SM, Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC. 2006. Physiological regulation of ATP release at the apical surface of human airway epithelia. J. Biol. Chem. 281:22992–23002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Okuda K, Aso Y, Nakayama J, Sonomoto K. 2008. Cooperative transport between NukFEG and NukH in immunity against the lantibiotic nukacin ISK-1 produced by Staphylococcus warneri ISK-1. J. Bacteriol. 190:356–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoskins J, Alborn WE, Jr, Arnold J, Blaszczak LC, Burgett S, DeHoff BS, Estrem ST, Fritz L, Fu DJ, Fuller W, Geringer C, Gilmour R, Glass JS, Khoja H, Kraft AR, Lagace RE, LeBlanc DJ, Lee LN, Lefkowitz EJ, Lu J, Matsushima P, McAhren SM, McHenney M, McLeaster K, Mundy CW, Nicas TI, Norris FH, O'Gara M, Peery RB, Robertson GT, Rockey P, Sun PM, Winkler ME, Yang Y, Young-Bellido M, Zhao G, Zook CA, Baltz RH, Jaskunas SR, Rosteck PR, Jr, Skatrud PL, Glass JI. 2001. Genome of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 183:5709–5717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yamamoto Y, Poyart C, Trieu-Cuot P, Lamberet G, Gruss A, Gaudu P. 2005. Respiration metabolism of group B Streptococcus is activated by environmental haem and quinone and contributes to virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 56:525–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen F, Cushion MT. 1994. Use of an ATP bioluminescent assay to evaluate viability of Pneumocystis carinii from rats. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2791–2800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Collins MD, Farrow JAE, Jones D. 1986. Enterococcus mundtii sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 36:8–12 [Google Scholar]

- 22. Higashide T, Takahashi M, Kobayashi A, Ohkubo S, Sakurai M, Shirao Y, Tamura T, Sugiyama K. 2005. Endophthalmitis caused by Enterococcus mundtii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1475–1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaufhold A, Ferrieri P. 1991. Isolation of Enterococcus mundtii from normally sterile body sites in two patients. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:1075–1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Murray BE. 1990. The life and times of the enterococcus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 3:46–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Willems RJ, Hanage WP, Bessen DE, Feil EJ. 2011. Population biology of Gram-positive pathogens: high-risk clones for dissemination of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 35:872–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tyrrell GJ, Turnbull L, Teixeira LM, Lefebvre J, Carvalho MDGS, Facklam RR, Lovgren M. 2002. Enterococcus gilvus sp. nov. and Enterococcus pallens sp. nov. isolated from human clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1140–1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ahmed FZ, Baig MW, Gascoyne-Binzi D, Sandoe JA. 2011. Enterococcus cecorum aortic valve endocarditis. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 70:525–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ferraris RP, Yasharpour S, Lloyd KC, Mirzayan R, Diamond JM. 1990. Luminal glucose concentrations in the gut under normal conditions. Am. J. Physiol. 259:G822–G837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chang DE, Smalley DJ, Conway T. 2002. Gene expression profiling of Escherichia coli growth transitions: an expanded stringent response model. Mol. Microbiol. 45:289–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, Yip L, Hashiguchi N, Zinkernagel A, Nizet V, Insel PA, Junger WG. 2006. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science 314:1792–1795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Corriden R, Insel PA. 2010. Basal release of ATP: an autocrine-paracrine mechanism for cell regulation. Sci. Signal. 104:re1 doi:10.1126/scisignal.3104re1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Praetorius HA, Leipziger J. 2009. ATP release from non-excitable cells. Purinergic Signal. 5:433–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC, Harden TK. 2003. Mechanism of release of nucleotides and integration of their action as P2X- and P2Y-receptor activating molecules. Mol. Pharmacol. 64:785–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gawron-Burke C, Clewell DB. 1982. A transposon in Streptococcus faecalis with fertility properties. Nature 300:281–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Casadaban MJ. 1976. Transposition and fusion of the lac genes to selected promoters in Escherichia coli using bacteriophage lambda and Mu. J. Mol. Biol. 104:541–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]