Abstract

Salmonella infection causes a self-limiting gastroenteritis in humans but can also result in a life-threatening invasive disease, especially in old, young, and/or immunocompromised patients. The prevalence of antimicrobial and multidrug-resistant Salmonella has increased worldwide since the 1980s. However, the impact of antimicrobial resistance on the pathogenicity of Salmonella strains is not well described. In our study, a microarray was used to screen for differences in gene expression between a parental strain and a strain of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis with reduced susceptibility (SRS) to the widely used antimicrobial sanitizer dodecyltrimethylammonium chloride (DTAC). Three of the genes, associated with adhesion, invasion, and intracellular growth (fimA, csgG, and spvR), that showed differences in gene expression of 2-fold or greater were chosen for further study. Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (real-time RT-PCR) was used to confirm the microarray data and to compare the expression levels of these genes in the parental strain and four independently derived SRS strains. All SRS strains showed lower levels of gene expression of fimA and csgG than those of the parental strain. Three of the four SRS strains showed lower levels of spvR gene expression while one SRS strain showed higher levels of spvR gene expression than those of the parental strain. Transmission electron microscopy determined that fimbriae were absent in the four SRS strains but copiously present in the parental strain. All four SRS strains demonstrated a significantly reduced ability to invade tissue culture cells compared to the parental strains, suggesting reduced pathogenicity of the SRS strains.

INTRODUCTION

Salmonella is a pathogenic Gram-negative rod that causes the disease salmonellosis. The young, elderly, and immunocompromised are most at risk for hospitalization (http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/foodsafety/). In the United States, Salmonella infection results in approximately $365 million a year in direct medical costs (http://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/foodsafety/). The emergence of strains of Salmonella with reduced susceptibility (SRS) to antimicrobials, such as sanitizers and antibiotics, is an ongoing health concern, as resistance to these compounds may lead to infections that are difficult to treat with antibiotics. There has been an increase of antimicrobial and multidrug-resistant Salmonella both in the U.S. and worldwide over the past 30 years (1, 2). SRS strains resistant to sanitizers may also exhibit cross-resistance to antibiotics (3). In a study by Karatzas et al., Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 cultures were developed to have reduced susceptibility to a range of agents, including a quaternary ammonium-based biocide, an oxidizing compound blend, a phenolic tar acids-based disinfectant, and triclosan. The quaternary ammonium-based biocide- and triclosan-exposed cultures showed the greatest cross-reactivity to a variety of antibiotics, including chloramphenicol, tetracycline, and ampicillin (3). Salmonella and other organisms can develop reduced susceptibility to sanitizers both in vitro and in the environment (4, 5, 6). Once a strain has developed reduced susceptibility to one sanitizer the MICs for other sanitizers and some antibiotics can also increase. This was shown in our laboratory with Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis strains trained up to dodecyltrimethylammonium chloride (DTAC). As the DTAC MIC increased, the MICs of benzylpenicillin and tetracycline also increased. (S. Stamm, unpublished data).

Pathogenic properties such as adherence, invasion, and growth inside intestinal epithelial cells have been well studied in Salmonella. Fimbriae are involved in the initial adhesion of Salmonella to intestinal epithelial cells and are necessary for infection (7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13). Inactivation of four fimbrial genes (fim lpfC, pefC, and csgB) resulted in a reduction of virulence in a mouse model (14). Two types of fimbriae have been detected in Salmonella under laboratory conditions: type 1 (Fim) and curli (Csg) fimbriae (15). Type 1 fimbriae are necessary for adhesion to epithelial cells and contribute to the colonization of the small intestine; curli fimbriae also adhere to intestinal epithelial cells (7, 8, 9, 16, 17, 18).

The Salmonella plasmid-encoded virulence genes spvR and spvABCD increase the growth rate of Salmonella inside macrophages and are required for systemic disease in mice (19, 20, 21). The spv operon is not necessary for adherence or invasion, but a nonfunctional spvR results in reduced virulence of Salmonella (20, 22, 23, 24).

Understanding the relationship between reduced susceptibility to sanitizers and pathogenicity is necessary to develop an appropriate response to the increase in resistance of many microbes to such sanitizers (4, 6, 25, 26). Using alternative sanitizers or a combination of sanitizers are two ways to address the issue. The present study was designed to determine if strains of Salmonella with reduced susceptibility to dodecyltrimethylammonium chloride (DTAC), a common sanitizer, have altered pathogenicity compared to the parental strain. DTAC is a quaternary ammonium compound that associates with the bacterial membrane causing leakage of cell contents (27). The fimA and csgG fimbrial genes and the spvR pathogenicity regulator gene were identified as being differentially expressed between the parental strain and SRS strain B by microarray. Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (real-time RT-PCR) was then used to compare the expression levels of these genes in four independent SRS strains. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to visualize fimbriae, and an invasion assay was performed to evaluate the efficiency of invasion of intestinal epithelial cells. SRS strains were found to be less invasive and had fewer fimbriae, and the majority had lower expression levels of fimA, csgG, and spvR than those of the parental strain, suggesting an overall decreased pathogenicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Enteritidis ATCC 4931 was designated the parental strain. Four strains with reduced susceptibility (SRS) to DTAC (B, C, D, and E) were developed from the parental strain as described previously (4). Briefly, the parental culture (ATCC 4931) was subcultured in increasing concentrations of DTAC. With each passage, the inoculum was taken from the culture with the highest concentration of DTAC that showed growth. This process was repeated until the MIC remained stable for three subcultures (27).

All strains were passaged each week and stored at room temperature. The parental strain was passaged in tryptic soy broth (TSB) (MP Biomedicals, LLC, Solon, OH) while the SRS strains were passaged in TSB containing 400 ppm dodecyltrimethylammonium chloride (DTAC) (Fluka, St. Louis, MO). Incubation was done at 37°C at 100 rpm unless otherwise noted. All strains were frozen in 10% glycerol at −80°C in aliquots for storage longer than 2 months. Strains were routinely confirmed as Salmonella by plating on xylose lysine deoxycholate (XLD) agar (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Sparks, MD) and tested with the RapidChek pathogen screening test kit (Strategic Diagnostics, Inc., Newark, DE) (27). DTAC stocks were made by dissolving DTAC in double-distilled deionized autoclaved water (dddH2O) and filter sterilized.

Eukaryotic cell culture.

Caco-2 cells (ATCC HTB37) were obtained from Gary Laverty (University of Delaware). Caco-2 cells were maintained in T25 tissue culture flasks with vented caps (HyClone, Wilmington, DE), in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA) with the addition of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone, Wilmington, DE), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 ppm streptomycin (Promega, Madison, WI). Media was replaced every 2 to 3 days, and cells were split when they became confluent (27).

Microarray.

ATCC 4931 (the parental strain) and one of the resulting SRS strains (strain B) were each grown with shaking to mid-log phase in 40 ml TSB for the parental strain and 277 ml for strain B. Fifty percent of their MIC of DTAC was then added to each culture, and incubation was continued for 150 min. RNA was extracted using RNAprotect bacteria reagent and RNeasy midi kit with on-column DNase digestion according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA was visually checked for degradation using a denaturing formaldehyde agarose gel according to instructions provided by Qiagen. RNA concentrations were measured in triplicate with a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer and NanoDrop 3.1.2 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Wilmington, DE) (27). RNA samples were shipped on dry ice to Athens, GA, for labeling and hybridization (27).

The nonredundant multiserotype microarray contains PCR products that cover 99% of all genes in the genome of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis PT4. Each gene is a separate spot printed onto Corning Ultra-GAPS glass slides (catalog no. 40015; Corning). Each glass slide contains triplicate identical arrays (28).

Probes were labeled with Cy3- and Cy5-dye-linked deoxyuridine triphosphate (dUTP) with direct incorporation during reverse transcription from total RNA to cDNA, following the method described by Pat Brown (http://cmgm.stanford.edu/pbrown/protocols/4_Ecoli_RNA.txt), with the following modifications: 50 μg of total RNA and 2.4 μg of random hexamers were prepared in 30 μl of water, and subsequently, all amounts and volumes of the components were doubled compared to the Brown protocol. Furthermore, 2 μl of RNase inhibitor (F. Hoffmann, La Roche Ltd., Basel, Switzerland) was added to the reverse transcription, and the reaction mixture was incubated at 42°C for 2 h. After the first hour of incubation, an additional 2 μl of Superscript II reverse transcriptase was added. Probes were purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and eluted in 1 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0). Probes were then dried and resuspended in 10 μl sterile water.

Probes were hybridized to the array overnight in 25% formamide, 5× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), and 0.1% SDS at 42°C following protocols suggested by the slide manufacturer for hybridizations in formamide buffer (Corning). The cDNA probes from the parental strain and SRS strain B were hybridized simultaneously to three replicate arrays. Microarrays were scanned with a ScanArray Lite Laser scanner (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Waltham, MA) using ScanArray Express 3.0 software.

Hybridization signal intensities for each gene spot were quantified using the QuantArray 3.0 software (Packard BioChip Technologies, Billerica, MA). Adaptive quantitation was used, and the local background was subsequently subtracted from the spot intensities. Data were normalized by calculating ratios of the contribution of each spot to the total signal in each. The expression ratio was calculated for each replicate probe in the three arrays, and the median of these three ratios was reported as the resistant strain versus the parental strain along with standard deviations.

Real time RT-PCR.

Growth conditions, RNA extraction, and determination of RNA concentrations were performed as described above. Reverse transcription of obtained total RNA was performed with the Omniscript RT kit (Qiagen Valencia, CA) on a PTC-100 programmable thermal controller (MJ Research, Inc., Waltham, MA). A random nonamer primer was used as detailed in the manufacturer's instructions. Four separate reverse transcription reactions were pooled, and a 1:100 dilution of the reverse transcription reactions was used in the real-time PCR (27).

Primers were designed using the SciTools application on the Integrated DNA Technologies website. The parameters used for primer design were as follows: (i) primer dimers and hairpin structures had a delta G value of >−9 kcal/mole, (ii) melting temperature Tm was between 59°C and 61°C, and (iii) no primer had a greater than 90% sequence similarity to nontarget DNA regions as reported by the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The word size was set to 7 and the expect threshold was set to 1,000. Primers were stored as 100 μM stock solutions, and aliquots of 5 pmol/μl were made. Each aliquot was thawed less than five times and all primers and cDNA were stored at −20°C (27).

The primer sequences are as follows: csgG forward, 5′-TGG CTG ACA TCA GAC ACA GCA TCA-3′; csgG reverse, 5′-TTC CTA TGA AGT ACA GGC AGG CGT-3′; fimA forward, 5′-TCC ATC GTC CTG AAT GAC TGC GAT-3′; fimA reverse, 5′-AGG AGA CAG CCA GCA AAT TAG GGT-3′; gyrB forward, 5′-AAT GAC AGT TCA CGC AGG CGT TTC-3′; gyrB reverse, 5′-ACT GGT TAT CCA GCG AGA TGG CAA-3′; spvR forward, 5′-CAA CAG ATC ACG CAC TGC ACA TCA-3′; and spvR reverse, 5′-ATC TGG TGT CTC CCG TTT CTT GGT-3′.

Primers were tested by observing the melting curve and by performing reverse transcription-PCR on a PTC-100 programmable thermal controller (MJ Research, Inc., Waltham, MA), followed by visually inspecting the resulting product lengths on ethidium bromide 1.5% agarose gels compared to a 100-bp DNA ladder (Promega, Madison, WI). The expected product lengths for each primer set were 113 bp for csgG, 102 bp for fimA, 195 bp for gyrB, and 83 bp for spvR (27).

During real-time RT PCR, 5 μl of cDNA (diluted 1:100 from the RT reaction) and 0.5 ng/μl of the forward and reverse primers were used. Each 96-well plate contained four replicates of each sample, and three replicate plates were run on separate days. The cycling temperatures were 95°C for 15 min, then 40 rounds of 95°C for 15 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. Disassociation curves were performed at the end of each run. Sybr green (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) technology was used to detect the levels of DNA. The ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system and ABI Prism 7000 SDS software were used to visualize the results (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA). The QuantiTect Sybr green PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Standard curves for each of the primers were made using at least three replicate plates with each plate containing three wells per sample. The parental strain's cDNA was used in all standard curves. The gene gyrB was used as an internal control (29). The calculations to determine fold change were used as described by Pfaffl (27, 30).

Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired Student's t test on the GraphPad software website.

TEM.

Samples were visualized with the CE 902 transmission electron microscope (TEM) (Carl Zeiss SMT, Inc., Thornwood, NY) with Soft Imaging System Mega View II (digital camera) (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions GmbH, Münster, Germany) or the Libra 120 TEM (Carl Zeiss SMT, Inc., Thornwood, NY) with DigitalMicrograph software (Gatan, Inc., Pleasanton, CA). At least three separate overnight cultures were visualized for each strain. Up to 10 images were taken of each overnight culture for a minimum of 30 images per strain. Each image was counted once and showed at least one bacterium. Images were categorized into three groups: bacteria having no fimbriae, less than 15 fimbriae, or more than 15 (many) fimbriae (27).

A single colony from each strain was grown overnight in TSB containing 400 ppm DTAC for SRS strains and TSB with no DTAC for the parental strain. The cultures were then passaged in fresh TSB with no added DTAC and grown overnight. The overnight cultures were plated on XLD and used for TEM imaging. Only cultures with the expected phenotype on XLD (black colonies) were included in the results (27).

For staining, 300 mesh copper grids with Formvar carbon support films (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) were treated with poly-l-lysine by floating the grids on 19 μl of a 0.01% poly-l-lysine solution (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 30 min. Treated grids were air dried for 2 or more hours. Treated and air-dried grids were floated on 19 μl of undiluted overnight culture for 1 min, washed via floating on filtered phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 20 s, stained by floating on two separate 19 μl drops of 5% ammonium molybdate (filtered) for 5 to 10 s, and dabbed with filter paper after each staining step (31, 32, 33). The grids were air dried for at least 1 h before use. Each sample was prepared on duplicate grids (27).

Invasion assay.

The following protocol was designed from elements in a number of publications (34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39). The Salmonella enterica parental strain was grown in TSB. SRS strains were grown in TSB containing 400 ppm DTAC. All strains were grown for 18 h with shaking. Approximately 106 washed Salmonella enterica cells in 100 μl Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) (Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA) were added to 105 Caco-2 cells growing in 2 ml of DMEM with 10% FBS in Falcon 24-well tissue culture plates (product no. 353047; Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). After 60 min of incubation at 37°C, the cells were washed with HBSS three times. Two milliliters of DMEM containing 10% FBS and 75 ppm gentamicin sulfate (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) were added. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 90 min. After washing three times with HBSS, the Caco-2 cells were lysed with 1 ml of 1% Triton X-100 in HBSS and pipetted vigorously. The lysate was plated on Trypticase soy agar (TSA) and incubated overnight at 37°C. CFU of the inoculum and lysate were counted the following day. Three control wells were used: Caco-2 cells with no Salmonella enterica, Salmonella enterica with no Caco-2 cells, and no Salmonella enterica or Caco-2 cells. No colonies grew from any of the control wells. The limit of detection was 101 cells/ml. Invasion ratios were calculated by dividing the lysate CFU by the inoculum CFU (27).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Microarray analysis of gene expression in a SRS strain.

The microarray showed that one-third of SRS strain B's genome expression differed from the parental strain by a factor of 2-fold or more. The genes chosen for further study are presented in Table 1. Many other genes associated with pathogenicity also had lower levels of expression in SRS strain B (27). The microarray also showed many additional differences relating to functions other than pathogenicity, and all data are available at GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the series number GSE41606. This indicates that there are multiple effects on bacteria exposed to antimicrobial agents.

Table 1.

Expression levels of selected genes from the microarray of SRS strain B

| Gene | Description | Fold differencea |

|---|---|---|

| fimA | Major type 1 fimbrin subunit | 0.02 |

| csgG | Putative regulator in curli assembly | 0.29 |

| spvR | Regulator of spv operon (Salmonella plasmid virulence) | 0.16 |

| gyrB | DNA gyrase, subunit B (type II topoisomerase) | 1.31 |

The fold difference is the expression level of SRS strain B compared to the expression level of the parental strain.

Real-time RT-PCR assays.

All four SRS strains showed a strong and very significant decrease in expression levels (P < 0.0001) for fimA, ranging from 180- to 15,000-fold, compared to the parental strain (Fig. 1A). The decrease in expression levels (P < 0.0001) for csgG ranged from 11- to 164-fold for all four SRS strains (Fig. 1B). The expression levels for spvR varied among the isolates examined. Strain B showed a nonsignificant 3-fold increase in expression levels (P > 0.05) for spvR compared to the parental strain, while the other three SRS strains had a significant decrease in expression levels (P < 0.0005), ranging from 9- to 175-fold (Fig. 1C).

Fig 1.

Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR relative fold difference of all SRS strains for fimA (A), csgG (B), and spvR (C) compared to the parental strain. The expression level of the parental strain for all genes is set as 1. Each graph depicts the expression levels of one gene for all four SRS strains.

All four SRS strains showed decreased expression levels of both fimA and csgG. This indicates that a decrease in expression of these genes may be necessary for reduced susceptibility to DTAC. Alternatively, this downregulation may be a collateral effect of resistance. Selectively upregulating the expression of fimA and csgG in these SRS strains and determining the subsequent MIC would determine if the downregulation of these genes is necessary for reduced susceptibility. The nonuniform gene expression of spvR between the four strains shows that altered gene expression of spvR is not necessarily linked to reduced DTAC susceptibility.

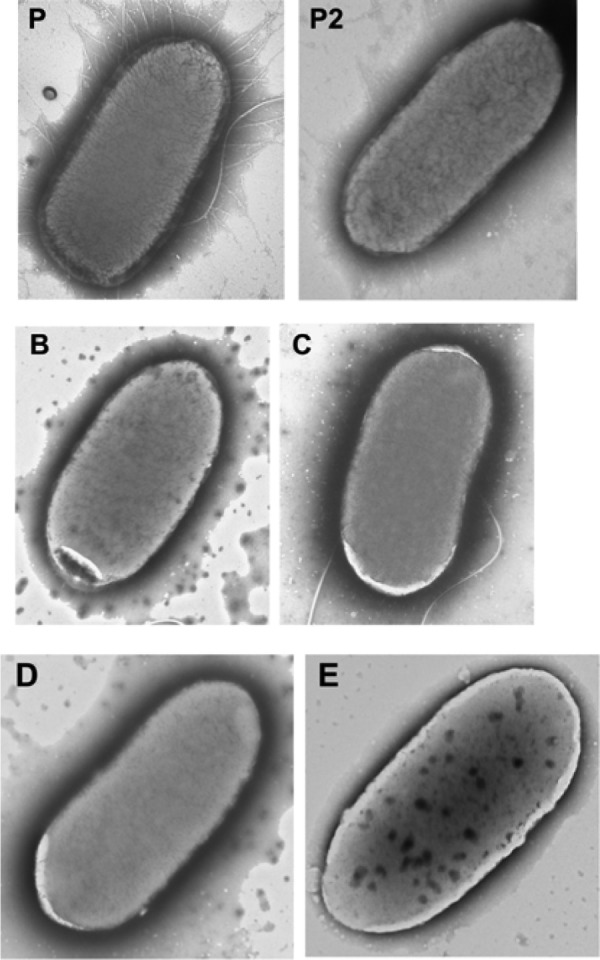

Electron microscopy of fimbriae.

TEM of parental and SRS strains gave similar results to the microarray and real-time RT-PCR results on the decreased transcription of the fimA gene. Less than 10% of the combined images of all four SRS strains contained any visible type 1 fimbriae. In contrast, all parental strain images contained visible type 1 fimbriae (Table 2). The SRS strains varied from 0 to 29% of images containing type 1 fimbriae (Fig. 2). This is the first time that a decrease in fimbriae has been associated with reduced susceptibility to DTAC. Specialized growth conditions are normally required to foster the growth of curli fimbriae. When present, curli fimbriae appear tangled when visualized by TEM, something we did not observe in our images.

Table 2.

Quantification of fimbriae

More than 15 fimbriae.

From 1 to 15 fimbriae.

Fig 2.

Transmission electron microscopy of fimbriae. P is the parental strain, and B, C, D, and E denote the SRS strains. The parental strain in image P is an example of many fimbriae, the parental strain in image P2 is an example of less than 15 fimbriae, and the SRS strains B, C, D, and E are examples of no fimbriae. Images P and C also contain one flagellum and two flagella, respectively.

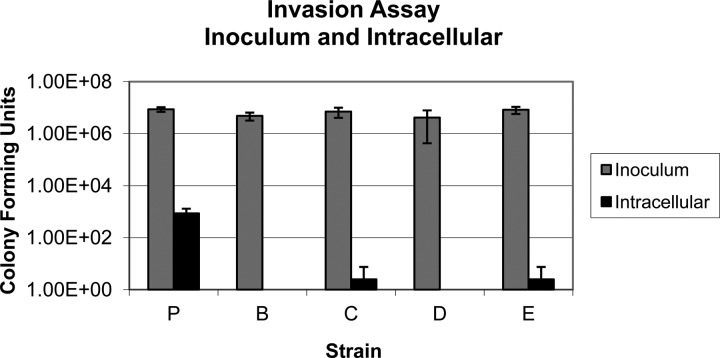

Invasion assays.

Invasion assays showed that all four SRS strains were less invasive than the parental strain in a Caco-2 cell culture model. The invasion ratio for the parental strain was 1.2 × 10−2, and the invasion ratios for the SRS strains C and E were 2.63 × 10−5 and 2.78 × 10−5, respectively. Intracellular levels of SRS strains B and D fell to below the level of detection, so their invasiveness was even lower than that of the other two SRS strains. Hence, the infectivity ratio of the parental strain was over 100-fold higher (P = 0.01) than that of the SRS strains (Fig. 3).

Fig 3.

Gentamicin protection assay in Caco-2 cells. The concentrations of the inoculums and intracellular values are shown separately. The intracellular concentrations of strains B and D fell below the detection limit of 10 CFU/ml.

The decrease in the expression and presence of fimbriae may explain the reduced invasion of the SRS strains. Fimbriae are a major virulence factor in Salmonella that has been shown to be necessary for both invasion and adhesion (7, 9, 10, 18). In other Caco-2 cell assays, the number of successfully invasive Salmonella cells was significantly decreased with prolonged exposure to multiple commercial biocide mixtures (3). Additionally, strains that were either curli or type 1 fimbria mutants showed a decreased number of successfully invasive Salmonella cells (9). Our results do not determine which type of fimbriae may have caused the decreased numbers of invasive cells. The invasion assay shows more than a 100-fold decrease in invasion for the SRS strains compared to the parental strain and is in agreement with the RT-PCR and TEM fimbrial studies. While attachment is a prerequisite to invasion, there may be additional factors that could contribute to the invasion assay results.

spvR.

While the spvR-controlled spvABCD genes are essential for virulence of Salmonella in animal models, these genes are not necessary for invasion of the intestinal epithelial cells (20, 22, 23, 24). In SRS strains C, D, and E, spvR was downregulated 9- to 175-fold (Fig. 1C). The decrease in expression of spvR in three of the four SRS strains suggests that these strains are less virulent than the parental strain.

csgG and pathogenicity.

The decrease in expression for csgG, curli fimbriae, ranged from 11- to 164-fold for the four SRS strains (Fig. 1B). These fimbriae stimulate the immune system as a pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) contributing to inflammation in vivo (40, 41, 42). Therefore, the decreased expression of curli fimbriae may lead to increased virulence. Further studies are necessary to investigate whether our SRS strains are, indeed, more or less virulent than the wild-type isolate.

Uniqueness of SRS strains.

Although the four SRS strains all had invasiveness and fimbrial defects, there were many differences observed among them. Their ultimate MICs ranged from 567 to 688 ppm DTAC compared to the parental strain, with a MIC of 100 ppm DTAC (Table 3). Previous differences were also seen in motility of the four SRS strains (4). Expression of the gene spvR differed among the SRS strains. spvR transcription levels were higher in strain B, but lower in the other SRS strains, than those of the wild type. While a more active spv operon may suggest better ability to grow inside macrophages (19, 20, 21), SRS strain B also had fewer fimbriae and a lower infectivity ratio than the parental strain. The ability to grow inside macrophages, associated with spvR, cannot confer an overall pathogenic advantage to SRS strain B if it cannot attach or invade. While fimbriae levels differ among the SRS strains, all SRS strains had lower expression levels of fimA and csgG than the parental strain.

Table 3.

MICs for all strains

| Strain | Average MIC of DTAC (ppm) |

|---|---|

| P | 100 |

| B | 663 |

| C | 567 |

| D | 650 |

| E | 688 |

Each of the four SRS strains described here appears to have unique characteristics. This uniqueness is tempered by all four SRS strains showing similar results for the invasion assay, fimbriae, and other studies (4, 27).

Conclusion.

The regular use of DTAC, which can lead to the production of SRS strains, may not pose a great risk. Although SRS strains exhibit cross-resistance to some antibiotics, we have shown that they are less able to invade intestinal epithelial cells (3, 4, 5). This decrease in invasion has also been found in strains with reduced susceptibility to other antimicrobials, including triclosan (3).

Our study, to our knowledge, is the first to report a decrease in expression of fimbriae in SRS strains. It also provides insight into the complexity of the pathogenicity of SRS strains. Of note are the interrelationships between the downregulation of csgG (a PAMP), the down- or upregulation of spvR (intracellular growth), and the downregulation of fimA (adhesion). Further study using animal models is needed to determine how the observed changes in gene expression integrate into phenotypes of the SRS strains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was based on studies carried out by Megan Kautz and included in her Master of Science thesis.

We thank Gary Laverty for providing us with the supplies and equipment to carry out the invasion assay using Caco-2 cells and Deborah Powell for help with the TEM experiments.

We acknowledge with thanks Steffen Porwollik's help with the microarray and his suggestions on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Butaye P, Michael GB, Schwarz S, Barrett TJ, Brisabois A, White DG. 2006. The clonal spread of multidrug-resistant non-typhi Salmonella serotypes. Microbes Infect. 8:1891–1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee LA, Puhr ND, Maloney EK, Bean NH, Tauxe RV. 1994. Increase in antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella infections in the United States, 1989–1990. J. Infect. Dis. 170:128–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karatzas KA, Webber MA, Jorgensen F, Woodward MJ, Piddock LJ, Humphrey TJ. 2007. Prolonged treatment of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium with commercial disinfectants selects for multiple antibiotic resistance, increased efflux and reduced invasiveness. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 60:947–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevenson NW. 2008. Reduced susceptibility of Salmonella enterica to biocides. M.S. thesis; University of Delaware, Newark, DE [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braoudaki M, Hilton AC. 2004. Adaptive resistance to biocides in Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli O157 and cross-resistance to antimicrobial agents. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:73–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oloya J, Doetkott D, Khaitsa ML. 2009. Antimicrobial drug resistance and molecular characterization of Salmonella isolated from domestic animals, humans, and meat products. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 6:273–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bäumler AJ, Tsolis RM, Heffronn F. 1996. Contribution of fimbrial operons to attachment to and invasion of epithelial cell lines by Salmonella Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 64:1862–1865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bäumler AJ, Tsolis RM, Heffron F. 1997. Fimbrial adhesins of Salmonella Typhimurium. Role in bacterial interactions with epithelial cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 412:149–158 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dibb-Fuller MP, Allen-Vercoe E, Thorns CJ, Woodward MJ. 1999. Fimbriae- and flagella-mediated association with and invasion of cultured epithelial cells by Salmonella enteritidis. Microbiology 145(Pt 5):1023–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horiuchi S, Inagaki Y, Okamura N, Nakaya R, Yamamoto N. 1992. Type 1 pili enhance the invasion of Salmonella braenderup and Salmonella Typhimurium to HeLa cells. Microbiol. Immunol. 36:593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonas K, Tomenius H, Kader A, Nomark S, Römling U, Belova LM, Melefors O. 2007. Roles of curli, cellulose and BapA in Salmonella biofilm morphology studied by atomic force microscopy. BMC Microbiol. 7:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sjöbring U, Pohl G, Olsón A. 1994. Plasminogen, absorbed by Escherichia coli expressing curli or by Salmonella enteritidis expressing thin aggregative fimbriae, can be activated by simultaneously captured tissue-type plasminogen activator (t-PA). Mol. Microbiol. 14:443–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiss-Muszkat M, Shakh D, Zhou Y, Pinto R, Belausov E, Chapman MR, Sela S. 2010. Biofilm formation and multicellular behavior in E. coli O55:H7 an atypical enteropathogenic strain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:1545–1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van der Velden AW, Bäumler AJ, Tsolis RM, Heffron F. 1998. Multiple fimbrial adhesins are required for full virulence of Salmonella Typhimurium in mice. Infect. Immun. 66:2803–2808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Humphries A, Deridder S, Bäumler AJ. 2005. Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium fimbrial proteins serve as antigens during infection of mice. Infect. Immun. 73:5329–5338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buchanan K, Falkow S, Hull RA, Hull SI. 1985. Frequency among Enterobacteriaceae of the DNA sequences encoding type 1 pili. J. Bacteriol. 162:799–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sukupolvi S, Lorenz RG, Gordon JI, Bian Z, Pfeifer JD, Normark SJ, Rhen M. 1997. Expression of thin aggregative fimbriae promotes interaction of Salmonella Typhimurium SR-11 with mouse small intestinal epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 65:5320–5325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tavendale A, Jardine CK, Old DC, Duguid JP. 1983. Haemagglutinins and adhesion of Salmonella Typhimurium to HEp2 and HeLa cells. J. Med. Microbiol. 16:371–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gulig PA, Doyle TJ. 1993. The Salmonella Typhimurium virulence plasmid increases the growth rate of Salmonellae in mice. Infect. Immun. 61:504–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Libby SJ, Adams LG, Ficht TA, Allen C, Whitford HA, Buchmeier NA, Bossie S, Guiney DG. 1997. The spv genes on the Salmonella dublin virulence plasmid are required for severe enteritis and systemic infection in the natural host. Infect. Immun. 65:1786–1792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsui H, Eguchi M, Kikuchi Y. 2000. Use of confocal microscopy to detect Salmonella Typhimurium within host cells associated with spv-mediated intracellular proliferation. Microb. Pathog. 29:53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fields PI, Swanson RV, Haidaris CG, Heffron F. 1986. Mutants of Salmonella Typhimurium that cannot survive within the macrophage are avirulent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83:5189–5193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gulig PA, Curtiss R., III 1987. Plasmid-associated virulence of Salmonella Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 55:2891–2901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Libby SJ, Lesnick M, Haseqawa P, Weidenhammer E, Guiney DG. 2000. The Salmonella virulence plasmid spv genes are required for cytopathology in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sumitomo T, Nagamune H, Maeda T, Kourai H. 2006. Correlation between the bacterioclastic action of a bis-quaternary ammonium compound and outer membrane proteins. Biocontrol Sci. 11:115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takenaka S, Tonoki T, Taira K, Murakami S, Aoki K. 2007. Adaptation of Pseudomonas sp. strain 7-6 to quaternary ammonium compounds and their degradation via dual pathways. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1797–1802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kautz MJM. 2010. The effects of reduced susceptibility of Salmonella enterica to DTAC on some indicators of pathogenicity. M.S. thesis; University of Delaware, Newark, DE [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porwollik S, Frye J, Florea LD, Blackmer F, McClelland M. 2003. A non-redundant microarray of genes for two related bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:1869–1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bearson BL, Bearson SM, Uthe JJ, Dowd SE, Houghton JO, Lee I, Toscano MJ, Lay DC., Jr 2008. Iron regulated genes of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in response to norepinephrine and the requirement of fepDGC for norepinephrine-enhanced growth. Microbes Infect. 10:807–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pfaffl MW. 2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic. Acids Res. 29:e45 doi:10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chuang YC, Wang KC, Chen YT, Yang CH, Men SC, Fan CC, Chang LH, Yeh KS. 2008. Identification of the genetic determinants of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium that may regulate the expression of the type I fimbriae in response to solid agar and static broth culture conditions. BMC Microbiol. 8:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saldaña Z, Xicohtencatl-Cortes J, Avelino F, Phillips AD, Kaper JB, Puente JL, Girón JA. 2009. Synergistic role of curli and cellulose in cell adherence and biofilm formation of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli and identification of Fis as a negative regulator of curli. Environ. Microbiol. 11:992–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zalewska B, Piatek R, Konopa G, Nowicki B, Nowicki S, Kur J. 2003. Chimeric Dr fimbriae with a herpes simplex virus type 1 epitope as a model for a recombinant vaccine. Infect. Immun. 71:5505–5513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeong JH, Song M, Park SI, Cho KO, Rhee JH, Choy EH. 2008. Salmonella enterica serovar Gallinarum requires ppGpp for internalization and survival in animal cells. J. Bacteriol. 190:6340–6350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee CA, Jones BD, Falkow S. 1992. Identification of a Salmonella Typhimurium invasion locus by selection for hyperinvasive mutants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89:1847–1851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu S, Manges AR, Xu Y, Fang FC, Riley LW. 1999. Analysis of virulence of clinical isolates of Salmonella enteritidis in vivo and in vitro. Infect. Immun. 67:5651–5657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prieto AI, Hernández SB, Cota I, Pucciarelli MG, Orlov Y, Ramos-Morales F, García-del Portillo F, Casadesús J. 2009. Roles of the outer membrane protein AsmA of Salmonella enterica in the control of marRAB expression and invasion of epithelial cells. J. Bacteriol. 191:3615–3622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steele-Mortimer O, Méresse S, Gorvel JP, Toh BH, Finlay BB. 1999. Biogenesis of Salmonella Typhimurium-containing vacuoles in epithelial cells involves interactions with the early endocytic pathway. Cell Microbiol. 1:33–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Su J, Gong H, Lai J, Main A, Lu S. 2009. The potassium transporter trk and external potassium modulate Salmonella enterica protein secretion and virulence. Infect. Immun. 77:667–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hammar M, Bian Z, Normark S. 1996. Nucleator-dependent intercellular assembly of adhesive curli organelles in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93:6562–6566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olsén A, Jonsson A, Normark S. 1989. Fibronectin binding mediated by a novel class of surface organelles on Escherichia coli. Nature 338:652–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tükel C, Raffatellu M, Humphries AD, Wilson RP, Andrews-Polymenis HL, Gull T, Figueiredo JF, Wong MH, Michelsen KS, Akcçelik M, Adams LG, Bäumler AJ. 2005. CsgA is a pathogen-associated molecular pattern of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium that is recognized by toll-like receptor 2. Mol. Microbiol. 58:289–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]